Abstract

We investigate cultural and structural sources of class differences in youth activity participation with interview, survey, and archival data. We find working- and middle-class parents overlap in parenting logics about participation, though differ in one respect: middle-class parents are concerned with customizing children’s involvement in activities, while working-class parents are concerned with achieving safety and social mobility for children through participation. Second, because of financial constraints, working-class families rely on social institutions for participation opportunities, but few are available. Schools act as an equalizing institution by offering low-cost activities, allowing working-class children to resemble middle-class youth in school activities, but they remain disadvantaged in out-of-school activities. School influences are complex, however, as they also contribute to class differences by offering different activities to working- and middle-class youth. Findings raise questions about the extent to which differences in participation reflect class culture rather than the objective realities parents face.

Keywords: Extracurricular Activities, Organized Activities, Leisure Activities, Youth, Families, Neighborhoods, Schools, Adolescents

Prior research links participation in structured activities to social stratification through its effects on college attendance and destination (Kaufman and Gabler 2004; Gabler and Kaufman 2006; Karabel 2006; Soares 2007; Stevens 2007). To the extent that disadvantaged groups evidence lower participation than advantaged ones, organized activities become a mechanism through which social inequality is maintained and reproduced. A class gap in participation is well established; yet, disagreement exists over explanations for its cause, with some authors focusing on cultural explanations and others on more structural ones (Furstenberg et al. 1999; Lareau 2002, 2003; Lareau and Weininger 2008a; Hughes 2008; Hofferth 2008). Based on qualitative interviews with parents at two urban schools, we report findings on working- and middle-class children’s level and type of activity participation, parents’ expressed cultural logic regarding participation, and parents’ reasons for enrolling their own children in structured activities. Our approach allows us to explicitly recognize that social behavior often sits at the intersection of beliefs about what should occur (as informed by culture) and the ability to actualize those beliefs (as shaped by structure)i.

We find that working-class parents use participation in organized activities as part of their parenting strategies, and articulate many of the same reasons for doing so as their middle-class counterparts. Further, we find that the in-school activity profiles of working- and middle-class youth are strikingly similar, while the two groups differ in their out-of-school activities. That the class gap in activity participation is small within schools, but substantial outside of schools suggests that schools play a critical role in equalizing access to activity participation opportunities across social class groups. What requires explanation, then, is not the lack of involvement in activities by working-class youth, but their low levels of participation in activities that are not organizationally tied to schools.

We argue that because of financial constraints, working-class families rely on social institutions for affordable participation opportunities, but have access to few such institutions beyond schools and churches, which are the ones prevalent in their neighborhoods. This is consistent with beliefs expressed by working-class parents regarding the value of activity participation for their children, the concentration of their children’s participation in school and religious activities, as well as the virtual lack of participation outside of school in the kinds of elite activities that colleges and universities value. Thus, almost a decade after publication of Lareau’s (2002) influential study, we find that working-class parents in our sample are quite supportive of organized activities, but their children participate in fewer and different activities than their middle class counterparts due to limited financial and institutional resources. We conclude that emphasis on organized activities by working-class parents is insufficient to close the class gap in activity participation because of structural constraints that they face.

SOCIAL CLASS AS CULTURE AND SOCIAL CLASS AS STRUCTURAL LOCATION

We argue that to fully understand class differences in youth participation in organized activities, we must extend our analytical lens beyond parenting logics to include the structural location of families. Doing so will help us distinguish between conceptualizing social behavior as the product of values, beliefs, and attitudes that people hold on the one hand, and conceiving of behavior as structured by differential access to resources—the result of what Barry Wellman (1983: 163) terms the “social distribution of possibilities.” Only then can we identify the ways in which social class acts as culture and as structure in producing group differences in activity participation.

In Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Lareau (2003) argues that divergent cultural logics exist among America’s social classes, leading to differential management of children’s time, including the time they spend in organized activities. In the middle-class homes in her study, she observed what she terms “concerted cultivation”—a cultural logic to parenting practices that emphasizes structure, language use, and interaction with dominant social institutions. In contrast, working-class and poor families displayed what she calls the “accomplishment of natural growth,” which involves relatively unstructured days, use of directives with children, and general avoidance—even distrust—of dominant social institutions. Although middle-class parents use enrollment in extracurricular activities as a means to cultivate children’s talents and skill, working-class parents, according to Lareau, are comfortable giving their children comparatively greater autonomy in how they spend free time and emphasize enrollment in activities less (Lareau 2003; Lareau and Weininger 2008a). As a result, middle-class and working-class children evidence different levels of involvement in structured activities. When combined with other class differences in parenting strategies, class gaps in activity participation help to reproduce social class advantage and disadvantage across generations.

Chin and Phillips (2004) come to a different conclusion. They investigate the ways in which cultural, social, and “child” capital shape children’s participation in organized activities in the summer. Findings from their research suggest that class differences in activities arise from differences in financial resources, knowledge of ways to develop children’s interests, and information about how to connect children to activities.

An ecological perspective on social behavior implicates parenting practices in class gaps in structured activity participation, but in a different way than Lareau’s work, by conceiving of parenting as the result of characteristics and processes that take place not only within the family (i.e., Lareau’s focus), but also in neighborhoods and the wider community in which the family is embedded (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Luster & Okagoti 1993; Kotchick and Forehand 2002). Indeed, there is a growing literature on the relationship between neighborhood context and parenting, with much of it reporting negative relationships between disadvantaged neighborhood conditions (e.g., poverty, level of danger) and desirable parenting practices (e.g., demonstration of warmth, consistent discipline) (Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, and Duncan 1994; Mohr, Fantuzzo and Abdul-Kabir 2001; Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, and Jones 2001; Letiecq and Koblinsky 2004). For example, Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, Elder, and Sameroff (1999) investigate neighborhood effects on parenting strategies in urban areas. They find two approaches to emerge: promotive strategies (which nurture and develop children’s talents and opportunities) and preventive strategies (which attempt to reduce children’s exposure to dangerous circumstances). Parents in high-resource neighborhoods are more likely to engage in promotive strategies by enrolling their children in structured activities, while parents in low-resource communities were more likely to use preventive strategies, primarily through keeping their children at home.

Although Furstenberg et al. (1999) do not directly assess class differences in structured activity participation, their research has implications for our understanding of those differences given the correlation between social class status and neighborhood location in America. Findings from their study suggest that class differences in involvement in organized activities may reflect the differential location of middle- and working-class/poor families in America’s residential landscape and their responses to it rather than emanate from a class-based cultural logic. Jarrett (1995) comes to that very conclusion after conducting an analytical review of studies on the parenting strategies of “socially mobile” youth in disadvantaged black neighborhoods. She finds evidence that parents’ dispositions towards organized activities are shaped by their perceptions of neighborhood danger.

Likewise, class differences in activity participation may reflect differences in the school context of working- and middle-class children; yet, processes of social reproduction and leveling by schools have yet to be fully explored with respect to class gaps in structured activity participation. School systems in the United States are characterized by both racial and class segregation, which create the conditions under which working- and middle-class children attend separate and, often, qualitatively different schools (Orfield and Eaton 1996; Kozol 1991, 2005). Bourdieu (1977) most famously theorized the ways in which schools reproduce social inequalities. McNeal (1999) considers how school structure and composition impact students’ participation in organized activities. He finds that school size and climate significantly affect participation, such that students in large schools and schools with difficult climates display lower levels of activity involvement. But size and climate are not the only features of schools that may matter. Teachers and administrators serve as gatekeepers to slots in extracurricular activities, recruiting students they perceive to be talented, while restricting others who are disqualified by academic standards (McNeal 1998). Lower academic achievement among working- versus middle-class youth, in combination with teachers’ views of them as less talented than their middle-class peers, may contribute to social class gaps in activity participation.

Conversely, schools may serve to narrow class differences in activity participation by equalizing opportunities to participate. Several researchers have revealed how schools ameliorate social class differences in a myriad of educational outcomes (Holloway and Fuller 1992; Entwisle and Alexander 1992; Downey, von Hippel, and Broh 2004; Condron 2009). Because a variety of structured activities are offered for little or no cost in public schools, schools may provide students with limited financial resources more opportunities to participate in activities than are available outside of school. To the extent that public schools that serve working-class youth offer a variety of organized activities, schools may have a “leveling” effect on class differences in participation much the same way they do with respect to other educational outcomes. Neighborhood institutions may play a similar role by offering low-cost activity options that are easily accessible, both financially and geographically, to working-class families. The leveling effect that schools and neighborhood institutions might have on organized activity participation has, thus far, been unexplored in the literature.

THE STUDY

To investigate the sources of social class gaps in organized activity participation, we sought to conduct a study that incorporates culture and structure. In the analysis that follows, we use in-depth, semi-structured interviews, survey and archival data to investigate social class differences in activity participation and parenting logics. Our research objective is to understand the reasons for the class gap in activity participation. We, therefore, investigate class differences in (a) structured activity involvement, (b) the types of activities in which children participate, (c) parents’ expressed beliefs about children’s involvement in activities and (d) structural influences on participation.

DATA AND FIELDWORK METHODOLOGY

We collected data from parents at two middle schools in a large northeastern city in order to produce a diverse group of respondents. One school is comprised predominantly of working-class and poor families and the other is comprised mainly of middle-class families, though both schools are racially and ethnically diverse (see Appendix A). The former is a neighborhood zoned school. It has 1960’s-style, functional architecture, and is located directly across the street from the local public library. The school has an informal feel, with colorful murals painted on its walls, and students’ poetry displayed. The school has a small cafeteria but does not have an auditorium. Teachers and administrators are friendly. On the days we visited, parent meetings were sparsely attended. The school is situated in a racially and ethnically diverse community that contains a mix of businesses and residences. Community residents are a combination of people who are working, unemployed, and currently out of the labor market. According to 2000 Census data, onethird of residents are poor, half of adults have less than a high school diploma, and fewer than half of adults are in the labor market.ii

The middle-class school is a city-wide magnet school that competitively selects students from the entire metropolitan area based on test scores and academic evaluations. The school is near the city’s center, which is a popular area that contains a mix of restaurants, otherbusinesses, and tourism. The school building has a rich architectural design and grandeur about it; one passes through tall columns to enter the building to be greeted by a bust of the historical figure after whom the school is named. Because it is an urban school, there is limited land surrounding it, and so students use the roof of the building as a social and recreational space. Despite having a large cafeteria, students often eat their lunch on the roof, and the school chess team and book club meet there during the lunch hour. On one of the days we visited, music drifted throughout the hallways as the school’s orchestra practiced in its very large, neoclassical-style auditorium. Parent meetings at this school are very well attended. On an evening we were there, parents of eighth graders alone filled the auditorium.

Although all of the middle-class parents were recruited from the magnet school, not all of the working-class parents were recruited from the zoned school. Four (4) working-class respondents come from the magnet school. The realities of class segregation in residential space and, thus, school catchment areas made it impossible to recruit middle-class respondents from the working-class neighborhood zoned school. Nevertheless, our sampling strategy has some benefits. First, by drawing working- and middle-class families from mostly separate schools, we avoid limits on class variation that may arise from sampling from a single school (Chin and Phillips 2004). Our sampling strategy produced a diverse sample, but without the potential drawback of constraints on class variation. Second, use of a city-wide magnet school gave us access to middle-class families in the city, which allows us to avoid introducing an urban-suburban divide mapped along class lines.

With the schools selected, we recruited families into our study via a multi-step process. First, we introduced the study at school parent meetings. Following the in-person introduction, we sent letters home with eighth-grade students that described the research project and invited their parents’ participation in our study. In total, eighty-seven (87) parents indicated their interest and completed a sociodemographic survey that gathered background information about the family, including a roster of household members, family income and other financial resources, education and occupation of caregiver(s), as well as self-reported race and ethnicity.

We employed a purposeful sampling strategy to select respondents for in-person interviews, which typically lasted between 2 and 4 hours. Our goal was to select a diverse sample of parents with respect to race, class, and immigration status rather than one representative of the schools from which they were recruited. Interview respondents vary in social class (working class and middle class), race/ethnicity (white, black, Latino, Asian, and mixed-race), and immigrant background (native born and immigrant). This analysis is based on an interview sample comprised of 29 working-class and 22 middle-class parents (n=51).iii While recognizing the robust debate around the question of how to measure social class, the approach we adopt is in service of analyzing the “ways in which unequal life conditions and individual attributes generate salient effects in the lives of individuals” (Wright 2008:336). Such an approach is consistent with a measure of class that is reflective of the “relationship of people to income-generating resources” (p. 331). Consequently, a bachelor’s degree held by at least one parent or caregiver served as our measure of middle-class status. This measure is consistent with Weber’s (1947) focus on skills and expertise. Moreover, this measure is intricately related to other indicators traditionally used to measure social class. Possession of postsecondary educational credentials affects access to and placement in the occupational structure (Blau and Duncan 1967; Collins 1979). It also affects the wages and salaries one can command in the labor market. In our sample, 60% of working-class families report earning less than $25,000 per year, while the same percentage of middle-class families report earning more than $75,000 per year.iv We examine differences in activities across income within the middle class to see whether there were differences in activity participation among those earning above and those earning below $75,000 per year (see Gilbert 2003).v

If we categorize our sample by race/ethnicity, we have 17 white, 16 black, 11 Latino, 2 Asian, and 5 mixed-race families. If we categorize these families by immigration status, we have 29 native-born, 17 mixed-status (where one parent is an immigrant and the other is not), and 5 immigrant sets of parents in our interview sample. Our use of a diverse sample engenders confidence that the experiences of working- and middle-class families reported in our study are not limited to those of blacks, whites, and those who are native born. Therefore, we contribute to the growing body of work on structured activity participation that incorporates the experiences of contemporary ethnic groups and immigrant populations (Chin and Phillips 2004; Dumais 2006).

In our interviews with parents, we ask about programs in which eighth-grade children participated at school and outside of school, extracurricular and after-school programs, as well as activity participation related to community, religious, and ethnic organizations. We recognize that collecting data on social behavior via interviews creates the possibility of a disconnect between parents’ responses to our questions and their actual behavior, but we feel that the activities reported are ones in which children participated, given that parents provide a great deal of information about them, such as their financial outlays associated with activities. Moreover, in other parts of the interview, we ask parents to describe their typical weekdays and weekends, which often revolve around their children’s schedules. Answers provided to those questions created a natural way to triangulate narratives about structured activity participation.

We leverage strengths of the interview methodology by employing two approaches to access parents’ cultural logics regarding youth activity participation. First, we utilize a structured activity participation scenario for discerning parents’ beliefs and values regarding structured activity participation. The scenario is a description of the organized activities and schedule of participation for a fictional child. As such, it is a hybrid instrument that sits between reliance on observations of parents’ behavior to reflect their beliefs about activity participation and soliciting their thoughts on this particular aspect of parenting. Here, we ask parents to comment on a fictional child’s activity participation schedule, which makes the inquiry into their beliefs about participation more concrete than if we had asked parents to comment on activity participation generally. Moreover, by constructing the scenario around a fictional child, we implicitly invite parents to step outside their own reality in an effort to free them from resource considerations as they evaluated the activity level depicted in our scenario.vi Thus, their responses should be expressions of their “conceptions of the desirable” (Kohn 1977:7) rather than expressions of what they think is possible given their present circumstances.

Separately, we asked parents to share with us their thoughts regarding their own children’s participation in activities (or nonparticipation). Our analysis of parents’ level of support for their children’s participation, as well as their reactions to the scenario, allows us to follow the advice of Diane Hughes (2008: 189) who encourages researchers to “explicitly ask parents and others about the beliefs that underlie their common and divergent practices.”

We created analytic codes that emanated from the data (consistent with inductive analysis) and developed a glossary for the coding scheme to articulate the meaning of codes. Utilizing a qualitative research software application, MAXQDA, we coded the text data into groups and more refined subgroups to identify patterns and variation in activity participation, responses to our structured activity participation scenario, and parents’ reasons for enrollment. Inter-rater reliability exercises were completed at every stage of analysis.

We define a structured or organized activity as one that is (1) adult led, (2) occurs on a regular basis, and/or (3) has an organizational or institutional affiliation. Structured activities did not include time spent alone or activities in which children merely hung out with friends or relatives (e.g., watching TV, playing games, going to the mall, etc.). With activities identified, we then grouped them into seven types: (a) sports, (b) cultural, (c) academic, (d) school service, (e) hobby, (f) youth development, and (g) religious. Activities that qualify as sports and hobby are well known, but what we classify as cultural, academic, school-service and youth-development activities may not be. Cultural activities include those that involve the arts (i.e., music, theater, and dance). Academic activities include ones that focus on academic pursuits (e.g., tutoring, science club, and book club). School-service activities are those that assist the school with its functioning (e.g., student government, yearbook, library assistance, student diplomat). Youth-development activities are ones designed to help children with life skills (e.g., scouting, secular teen groups). Finally, religious activities include church/synagogue/temple/mosque-going and other activities offered by places of worship, such as youth groups.vii

We incorporate social structure into our analysis by paying attention to the ways in which opportunities to adopt particular parenting practices are socially distributed. We do so by distinguishing between school-based and out-of-school activities. This distinction reveals the role that schools play in structuring opportunities for participation, particularly for working-class children. In addition, we use information gathered from the websites of both schools to form what we call a structured activity choice-set that each school offers its students. We then supplement this material with information obtained during interviews with our respondents. That is, we add to a school’s activity choice-set any school activity in which a respondent’s child participates but that is not listed on the school’s website. We believe this approach permits us to come very close to forming a comprehensive picture of the opportunities for participation in activities that each school offers its students.

SOCIAL CLASS DIFFERENCES IN STRUCTURED ACTIVITY PARTICIPATION

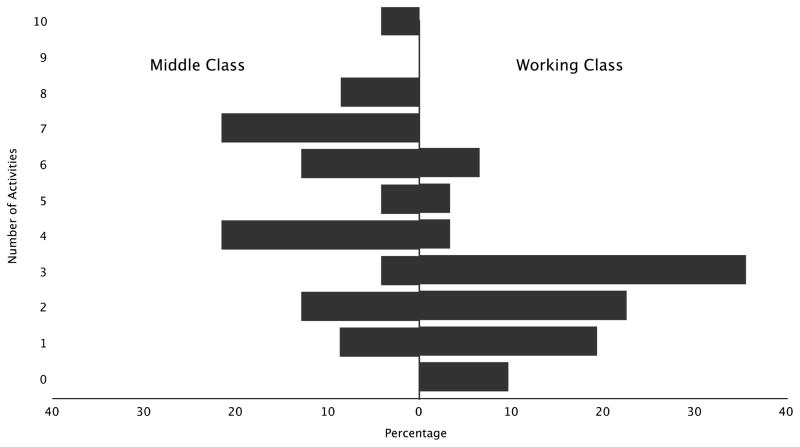

Our respondents report a total of 189 non-unique activities in which their children participated during their 8th grade year, ranging from as few as none to as many as 10 per child. Consistent with prior studies (Lareau 2003; Chin and Phillips 2004; Dumais 2006; Lareau and Weininger 2008), we observe class differences in participation, with the middle class having participated in the most activities (5.0 per child) and the working class having participated in the least (2.4 per child), on average (see Table 1).viii Examining the frequency distribution for working- and middle-class families reveals further differences between them. Middle-class families are much more evenly distributed across the entire range of activity participation than are working-class families (see Figure 1). The majority of working-class families are concentrated at the lowest levels of participation, with three of them reporting no activities. Nevertheless, participation among working-class children is not trivial. Collectively, working-class parents reported 74 non-unique activities. Additionally, involvement in activities is widespread among working-class families; 26 of 29 families reported activities in which their child(ren) participated.

Table 1.

Level of Participation in Structured Activities by Working- and Middle-Class Youth.

| Social Class | No. Activities | Means |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | In School | Outside School | ||

| Middle Class | 115 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| Working Class | 74 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

Note: Sample contains 23 middle-class and 31 working-class youth.

Figure 1.

Distribution of middle- and working-class families across number of reported structured activities

Among the children in our sample who participated in multiple activities, it is typically the case that they were involved in different activities rather than multiple instances of the same activity. In other words, although some youth may have, for example, played the same sport both at school and on a neighborhood team, most youth became involved in myriad activities during the span of their eighth-grade year. Two examples illustrate the point: Quentin, a white child from a working-class family, participated in four activities: golfing at school, science club, he served as a library assistant, and participated in a program that teaches leadership skills to youth. Nathan, a white child from a middle-class family, participated in seven activities: street hockey, soccer, baseball, and private music lessons. He also attended synagogue, Hebrew school, and participated in a youth group at the synagogue.

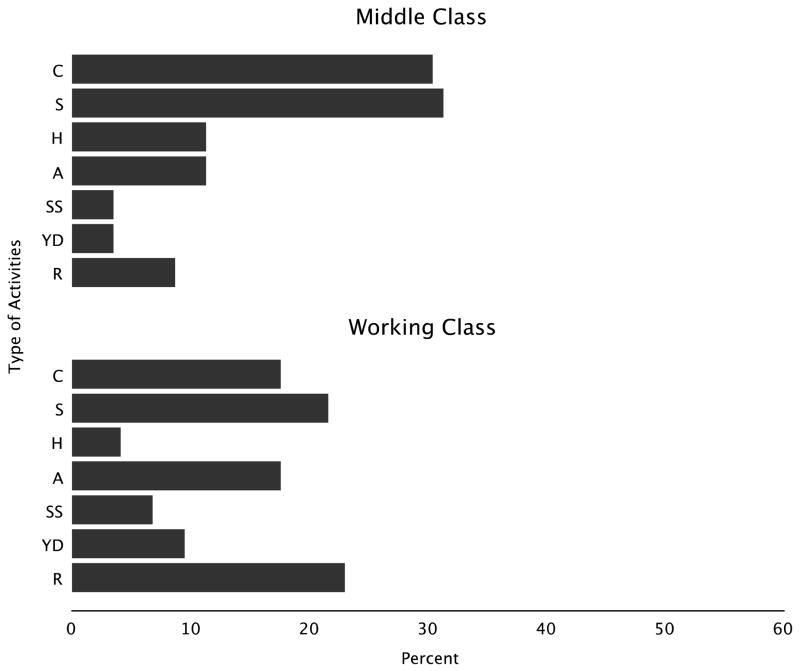

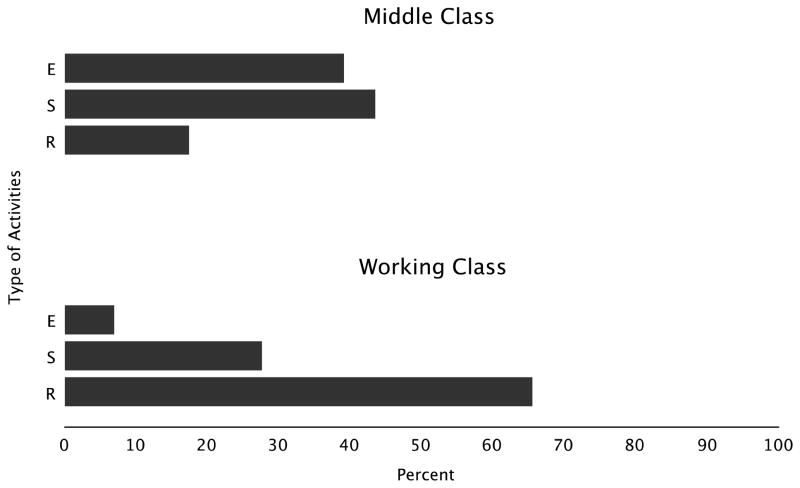

Figure 2 presents the percentage distribution of activities across activity types for each social class, and paints an overall portrait of the kinds of activities in which children and parents became involved. Working-class children participated in myriad activities. Among the seven types that we identify, religious, sports, academic, and cultural activities were the most prevalent reported by working-class families, accounting for 80% of their activities. These types of activities were also popular among middle-class families, but to a somewhat different degree.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of structured activities across activity types by social class location.

Note: C=cultural; S=sports; H=hobby; A=academic; SS=school service; YD=youth development; R=religious.

There are, however, differences in the kinds of activities working- and middle-class families invested their time, money, and energies. Three are worth nothing. First, religious activities—often church attendance—account for a sizeable percentage of the activities of working-class children, but only a small proportion of those of middle-class children (23.0% compared to 8.7%). Second, hobby activities, such as chess, were relatively popular among middle-class children, but account for a much smaller percentage of the activities of their working-class peers (11.3% versus 4.0%). And third, participation in youth-development activities is almost absent among middle-class children, though it accounts for 9.3% of the activities of working-class children.

Together, these findings reveal that while activity participation among working-class families is not as high as it is among their middle-class counterparts, participation is routine for them. Children from both social classes participated heavily in sports and cultural activities, which are precisely the kinds of activities that are expected to have implications for later educational outcomes. Kaufman and Gabler (2004) find that participation in interscholastic sports is associated with increased likelihood of attending college. Such activities are expected to facilitate students’ academic achievement by helping them create identities that are tied to their school and its mission. Likewise, cultural activities are associated with increased odds of attending elite colleges, as participation in such activities may signal to teachers and admissions officers that students are familiar with and appreciate middle-class norms and culture (Soares 2007). That working- and middle-class children heavily participate in such activities suggests that both groups of parents have positioned their children in activities that may pay educational dividends. These commonalities exist in the presence of an important difference, however. Despite meaningful participation in cultural activities by working-class children, adolescents from middle-class families have even greater involvement in such activities, in addition to higher participation in hobby clubs, both of which are associated with enrollment in elite colleges and universities (Kaufman and Gabler 2004; Gabler and Kaufman 2006), while working-class children make greater investments in religious activities.

PARENTS’ EXPRESSED CULTURAL LOGIC

Parents’ Responses to the Structured Activity Participation Scenario

For our first approach to assessing parents’ beliefs about involving children in organized activities, we analyze their responses to our structured activity participation scenario. Recall that the scenario is designed to free parents from the particular constraints in their personal lives so that they may express their “conceptions of the desirable,” (Kohn 1977:7) unencumbered by what they feel is merely possible. In it, we describe the activities and schedule of a fictional child. The scenario reads:

Some children participate in many school and out-of-school activities. For example, let’s take an 8th grader who plays in the school band, which means he/she has band practice for an hour and a half three times a week after school. He/She also plays on a neighborhood sports team and has practice every Saturday afternoon and has a game once a week. Sometimes the games are away and so he/she travels with the team.

After we read this scenario to parents, we invited their responses with the question: “What do you think of this child’s level of participation in extracurricular activities?” Table 2 displays the results of this exercise.

Table 2.

Percentage Distribution of Middle-Class and Working-Class Responses to Structured Activity Participation Scenario.

| Social Class | Depends on Child | Too Much | Too Little | Good Amount | Qualifiers to Good Amount

|

Missing | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | If Schoolwork is Ok | If Family is OK | |||||||

| Middle Class | 18.2 | 27.3 | 4.5 | 45.5 | 31.8 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 100.0 |

| Working class | 0.0 | 31.0 | 0.0 | 58.6 | 41.4 | 17.2 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 100.0 |

There are several points to take away from this table. First, a similar percentage of working- and middle-class parents respond positively to the fictional child’s level of activity participation— 58.6% and 45.5%, respectively, indicated it was “good” or “great.” Moreover, parents of both classes indicate caveats to their positive disposition toward the schedule of activities. Yet, those caveats reveal possible differences in concerns between the two groups. Working-class parents were concerned with whether the child’s activities interfered with their ability to do well in school (17.2%) while proportionally fewer middle-class parents expressed that concern (9.1%). Veronica, a Latina immigrant working-class mother who was out of work but seeking employment at the time of the interview, says:

Um…I think [the fictional child’s level of participation in activities is] excellent. Um…only if, if he can maintain his grades. If he can’t…that’s what I tell my daughter…my kids. ‘If you can maintain your grades, have good grades, um, then you can participate.’ If I see that the grades are slipping, then I tell them ‘no.’

Similarly, Carla, a working-class African-American mom who works as an assistant preschool teacher says:

Um…that would…it seemed like a lot, but in terms of, if it’s something that works out for the child and his grades are still where they should be, then I would say that it is still a good outlet…because it’s time that they’re not gettin’ in trouble or finding [out] about things that they shouldn’t be into. So, it is a busy, busy schedule, but I don’t know, our schedule might be the same (laughter).

Second, working- and middle-class parents are similar in their assessment that the amount of participation in our scenario is unequivocally too much for our fictional child (31.0 and 27.3%, respectively). Moreover, they arrive at that assessment for similar reasons. Both groups express concerns about (a) the lack of rest or downtime such a schedule would afford the child, (b) the complicated logistics and stress placed on parents inherent in such a schedule, and (c) the amount of time such a schedule requires. Working-class parents in this “too much” group differ from their middle-class peers only in their concern that a busy activity schedule might lower the amount of time our fictional child has available to do homework.

Perhaps working- and middle-class parents are similar in their assessment of the scenario, in part, because some middle-class parents, but no working-class parents, made their responses contingent on the child in question. Almost a fifth (18.2%) of middle-class parents indicate that they could only evaluate the level of participation of our fictional child in light of what the child wants or is capable of managing successfully. For example, Bette, a white, middle-class attorney states:

I think it depends on the kid. There are some kids that thrive on that and there are some kids who stress on that. So, it just really depends on the kid.

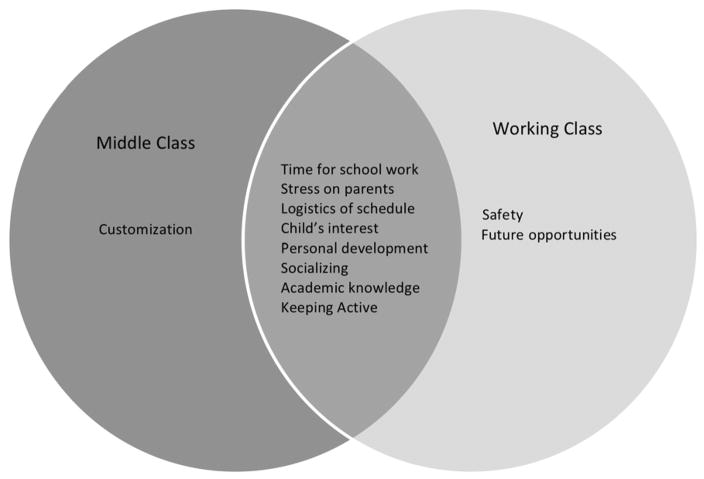

Thus, working-class parents in our sample are as likely as their middle-class peers to view active participation in the scenario positively. Only when they see participation as a threat to children’s academic performance do they begin to waiver on whether an active schedule is positive for children. Among those who expresse concerns regarding our fictional activity schedule, worries about time for schoolwork was a prominent theme, but one not mentioned by middle-class parents. For their part, middle-class parents are distinctly concerned that the schedule fit with a child’s interests, capacity, and desired level of involvement; these concerns are not expressed by working-class parents.

Parents’ Support for Their Children’s Activity Participation

To understand parents’ cultural logics, we also analyze their thoughts about and reasons for supporting their own children’s participation (or nonparticipation) in structured activities.ix Although a variety of reasons for activity participation emerge within and across social classes, the majority of reasons fall into a relatively small set of categories. While other research finds that working-class parents support a parenting philosophy that does not emphasize enrollment in organized activities (Lareau 2003), we find much support for children’s participation among our working-class sample. Moreover, working- and middle-class parents offer similar reasons for their children’s participation, such as supporting their child’s interest in an activity, keeping active, personal development, increasing the academic skills of their children, and providing a venue for children to socialize with peers. We find, nevertheless, that working-class parents offer a number of reasons that are scarcely mentioned by their middle-class counterparts. Both groups of reasons—common ones and those unique to working-class parents—are explored below.

Shared Reasons for Supporting Participation in Structured Activities

Child’s Interest

For many parents in both social classes, their child’s interest in an activity is a primary reason for supporting it. Paula is a Latina middle-class teacher whose daughter participates in dance outside of school. She also participates in several school-based extracurricular activities including track, yearbook, chess, and choir. About the selection of her activities her mother says:

I let her choose the activities she wants to participate [in]. That’s her thing and as long as she’s happy, I’m happy. And I’ve sat in that car waiting for her sometimes over an hour. I just make sure I have a book in the car and I read and I’ll just wait. So, it’s her thing. If she wants to do it, do it.

Similarly, Tamara lets her daughter take the lead in deciding whether and in which activities to participate. Tamara is a working-class black mother who sorts packages for an international shipping company and whose daughter participates in softball, volleyball, cheerleading, drill team, basketball, soccer, and swimming as well as her church youth group. About her participation, Tamara says:

Hey, whatever suits her, as long as she watch herself and don’t get hurt, you know … She loves sports.

Personal Development

Both middle- and working-class parents cite personal development as a primary reason for their children’s participation in activities. Personal development through organized activities can include the learning of values of the larger society or social group (e.g., learning to cooperate with others), the development of adolescents’ personal qualities (e.g., overcoming shyness or gaining emotional well-being and maturity), or the learning of personal skills or lessons that may be useful or advantageous to have as children grow and transition into adulthood (e.g., how to persevere or handle rejection). Bette is a white middle-class mother whose daughter participates in Girl Scouts, acting classes, school book club, school guitar ensemble, a writing program at a local university, among several others. She also participated in two summer camps during the year of the interview, including a Buddhist family camp and film camp. Bette says that her daughter’s myriad activities are important in terms of self exploration:

I think it, you know, it opens doors and allows you to try new things and explore who you are, meet new people, and find out what kind of people you’re comfortable being around and how to be comfortable with different kinds of people.

Several parents emphasize that activities can teach young people life lessons and personal skills (e.g., persistence, determination, and handling rejection) that will aid them as they move toward adulthood. Rosa is a working-class Puerto Rican single mother of three who is an administrative assistant and whose daughter participates in tutoring and a salsa dance troupe. About participation in the troupe she says:

It helps them … there are certain moves that are difficult and they have to sit there and be able to figure it out, practice it, so it gives them that drive, that goal, like “I want to do this.” So, it teaches them to kinda fight to get where they want, where they need to be and to get better. It shows them that practicing gets better.

Academic Knowledge

Many parents across social class cite the acquisition of academic knowledge as an important reason for participation in extracurricular activities. This reason is primarily offered by parents whose children participate in tutoring programs or academic teams. Sarah is a working-class black mother whose daughter receives tutoring after school. Sarah works as a housekeeper at a hotel and likes her daughter’s participation in tutoring. She cites after-school programs as an indicator of a good school particularly because she does not feel that she has the knowledge to help her daughter with homework:

Um, I look for after-school programs…. I look for homework programs because the work that they teach the children now, I don’t know how to do it and my children come to me and say ‘Mom how do you do this? I’m lost!’ I’m lost. I can’t—the math is new math and the way they, the teachers, teach them is different from what I was taught. And I’ll show them my way and they say, ‘No this is how we do it.’

Likewise, Grace, a middle-class paralegal of African-American and Asian descent whose daughter participates in math tutoring, cites academic knowledge as a primary reason for her daughter’s participation in this activity:

… she chose to go on her own because she was having problems with math. I’m good at math, but [her school’s] math is kinda like college math, so we kind of worked together. So, yeah, she picked that herself and I’m glad for it.

Keeping Active

Another reason for activity participation given by both working- and middle-class parents is that it keeps their children busy and active. For example, Grace (mentioned above) says “I don’t see any drawbacks [to participation in activities]. The benefits—that it keeps her busy.” Juliette, a working-class black Caribbean nurse’s aide, says “You know, that’s me. Keep her busy, you know.” Olivia is a middle-class white parent with a multiracial child. Her son participates in basketball and track at school as well as ice hockey and keyboard lessons. Olivia, a teacher, says: “I really encourage him to, because like I said, I don’t like him to sit at home all the time. And I don’t want him hanging out, that kind of thing. So, yeah, I’m really happy that he does it.”

Socializing

Both middle-class and working-class parents indicated that they appreciate extracurricular activities because they give children an opportunity to get to know and socialize with other kids. For example, Holly, a white middle-class social worker whose son participates in basketball at school and basketball, baseball and football outside of school says, “the benefits are, you know, definitely socializing.”

Anne is an African-American working-class caseworker whose daughter participates in two church youth groups and tennis camp in the summer. Of her daughter’s participation in her church youth groups she says:

I think it’s great. I think it’s great. She’s really well-rounded….um….that she’s just not focusing on the religious aspect. But it’s very social for her, too. They don’t….the thing I do like about this group is they have movie night where they’ll watch…um…it’s not all just religion…it’s well-rounded….they go bowling….they ride bikes.”

She goes on to say,

It’s keeping her faith-based, but it’s also expanding the group that she’s in. Primarily since [it] is such a small school, she’s able to meet other kids who don’t go to that school. So, she has other outside interests, which is good.

Jerome is an African-American middle-class father who has his own consulting business and works from home. His son participates in a myriad of cultural and academic activities both in and outside of school, which gives his son an opportunity to “meet girls” and socialize with other kids. He says:

I think sometimes he just kind of hangs out at school or hangs out with other kids after, you know, not doing anything bad but just hangs out at school with other kids or hangs out in the library or hangs out and just chats with other kids and you know, gets to know some of the kids that are in the choir and all that. So, it’s like a social function.

Variation across Social Class in Support for Participation in Structured Activities

While middle- and working-class parents share some reasons for supporting involvement in extracurricular activities or viewing them as beneficial, other reasons for participation were particular to working-class parents.

Safety

Ten (10) working-class parents (but no middle-class parents) cite keeping children safe and away from trouble as an important reason for their children’s participation in structured activities. These parents describe their neighborhoods as dangerous places and prefer to see their children stay in the environment of school or other locations where organized activities take place. Among those who cite safety as a primary reason for their children’s activity participation, 80% also articulate concerns about the level of danger in their neighborhood environment.

Patricia is a working-class African-American single mother who, at the time of the interview, is unemployed and looking for work. She has two sons who are fourteen and seventeen years old. Her youngest son participates in an academic program that is unaffiliated with the school, the youth-development program at school, and the school drama club. When asked about the extracurricular academic program that her son participates in she says, “…it’s really nice. It keeps the kids off the street…give them somethin’ to do.” She feels that her neighborhood has gotten more dangerous in recent years, and recounts the murder of a child in the neighborhood that contributes to her concerns about safety. She states: “Recently, a boy was killed for not selling drugs, for refusing to sell drugs. He got…they killed him.” This is something that she worries could happen to her own son while walking through the neighborhood, so she prefers to have him in extracurricular activities:

You know, they would kill you. Like I was saying, I’m concerned about [my son] traveling because I dress him nice and I’m afraid my son could go out there and get hurt for the garment he got on. I mean, this kid is actually—the guy [the victim] gave the guy his suede jacket and he shot him [the victim] in the back anyway ‘cause he [the assailant] wanted to see how it felt. This is what I fear, you know. I know I have to let them go. I have to let them venture out, but like I said, I’m an overprotective mother.

For Patricia, her son’s participation in extracurricular activities is a way of keeping him out of the neighborhood and safe.

Gabriela is a single working-class mother of three from Central America who works to support her family by cleaning houses. She, too, is very concerned about dangerous elements she sees in her neighborhood. When asked to describe her neighborhood, she replies: “I think it’s the worst. (chuckle) It’s the worst, but … the economic situation forces me to live where I live, unfortunately. But I ask God, well, that I can get out of there one day” (translated from Spanish). Gabriela does not want her children to spend time outside for their own safety. She states: “It worries me. I … the thing is, I want to know what it is that they’re doing, you see? I don’t know, I don’t trust the surroundings” (translated from Spanish). Her eighth grade son participates in a youth-development activity at school. As part of the program, her son tutors younger children after school. Gabriela feels her son’s involvement keeps him away from danger.

There are too many drugs … It’s dangerous. There, there in [this city], that school, it’s very dangerous around there … too many drugs, too many people selling it on every corner, and … definitely, well … we have to see all of it. The kids can see, and … and I thank God and this program…. Really, that’s what has helped keep him occupied, that after school he helps kids around the age of my youngest girl. It’s a program with … with parents that work like me, we don’t pay. It’s a great help. And that’s how my son hasn’t gotten involved with, with, with those people. Guns, drugs … with bad people (translated from Spanish).

When asked about how satisfied she is with her son’s participation in the after-school program she says:

Yes, I’m satisfied. Ah, yes, because it’s helped those kids a lot … a lot, that they not be on the street. Definitely, I don’t know who invented that, but … the nicest thing that could … I can see in … I can say that yes, kids that could be on the street with drugs, they’re entertained there (translated from Spanish).

Gabriela likes her son’s participation in the youth-development program because it keeps him indoors and reduces his exposure to the neighborhood. She says, “I try for them to stay (her emphasis) occupied. You understand?”

Future Opportunities

Another reason for supporting their child’s involvement in structured activities given by some working-class parents (5), but no middle-class parents, is that structured activities are linked to future opportunities. In this sense, working-class parents see their children’s activity participation as part of a plan for their children’s social mobility. Some parents see a link between activities and educational success, while others see the activities themselves as pathways to future opportunities. Polly is a working-class white mother of four. She is married and works at a national pet store chain. Polly’s eighth-grade daughter participates in a variety of extracurricular activities, such as church youth group, Civil Air Patrol, summer prep for military school, and a modeling program. Polly sees participation in these activities as part of a pathway to college:

All of it’s geared to getting them into a good college, which I like. The Civil Air… also does a lot of the college type thing. …If they finish the whole entire program in Civil Air, there’s grants available when they finish Civil Air to go to college through that program. Which is…one of the reasons why I put my son in it, because of the grants that would be available at the end of it, which [is] also part of the reason why I like [my daughter] being in it, because between the school, and the grants that are gonna be available because of the school, and then Civil Air’s grants, she’s got a very good chance of getting into an extremely good college.

Juliette, the nurse’s aide from the Caribbean, views her daughter’s extracurricular activities as part of a strategy to help her academically as well as give her ideas for future careers. Her daughter participates in the youth-development program at school and church band. As part of the youth-development program, her daughter receives help with homework, which is something Juliette feels is valuable:

For me, the benefit is that I see it’s helping the kids, you know, to do something after school. You know, helping the kids to do homework, is very good. You pushing the kids to do something for tomorrow, so …it’s very good.

Juliette feels that the youth-development program helps her daughter move toward a positive future, both by providing her daughter with homework assistance and teaching her particular skills that can make available future opportunities.

If she focus on so many things that learn at the [youth-development program], it could [set] her for tomorrow. …She says she wants to be nurse, pediatrician nurse, but probably when she wish she could change her mind, she say, “Ok, I learned…art at the [youth-development program], I think I’m gonna do art. I’m gonna be open [to] art school,” whatever. So, if she do that, that will be good, because she’s gonna show somebody else what she learned.

Entertainment and recreation are insufficient reasons to participate in structured activities according to Juliette. She only wants her daughter to participate in activities that provide something valuable for her future.

Some parents be happy to send the kids all over the place; let the kids [be] involved with so many different thing, you know, see the kids, see so many friends, they don’t care. But for me, for me it’s a little bit different. You know? I want my kids involved with something that I know is gonna [be] good for your life. I don’t see any basketball, I don’t see a lot of these activities [as] good. Do you understand? But for me … I, I really want to see my kids doing something, you know, make me happy about.

For some of the working-class parents in our sample, structured activities are not only desirable for their intrinsic value, they are important for their utility in securing future opportunities.

Making Sense of Parents’ Support for Youth Participation in Structured Activities

Overall, parents of both social classes are overwhelmingly supportive of their children’s participation in organized activities. Among those who view participation positively, 19parents expressed some drawbacks to it, which for most (16) include concerns about time, rushing, transportation, and potential over-scheduling that could reduce time for family, homework, and relaxation. These concerns are raised primarily by middle-class parents (12), particularly small business owners whose children are involved in more activities than children of other middle-class families. In only one case is a parent mostly unsupportive of activity participation; in this instance, a working-class father is unsupportive of his daughter’s involvement in activities (sports, in particular) because of concerns about outside influences on her. However, even this father expresses that he would like his daughter to take voice lessons, but can not afford them.

Together, our findings raise questions about the extent to which cultural logics explain the class gap in involvement in structured activities. Working-class parents in our study show a great deal of support for participation in organized activities in general, and for their children’s participation in particular, as do middle-class parents. To the extent that working-class families voice concerns about active participation schedules, they do so with concerns for children’s academic performance in mind. They also worry about coping with the logistics of getting children back and forth to activities given school and work schedules, along with the stress heavy participation places on parents, themselves. These concerns are similarly voiced by middle-class parents.

Consistent with prior work, however, is evidence that middle-class parents are interested in customizing their children’s experiences (Lareau 2003). A full 20% of middle-class parents, but no working-class parents, attempt to evaluate the activity schedule of our fictional child only from the perspective of the child’s wishes, talents, and ability to handle the commitments that such a schedule entails. For this group of middle-class parents, there is no universal value placed on a highly active versus a somewhat inactive participation schedule that exists apart from the child’s specific abilities.

Some of the reasons for supporting participation among the working-class are similar to those of middle-class parents (such as the child’s interest, personal development, and the acquisition of academic knowledge). However, some working-class parents, but no middle-class parents, primarily cite a desire to keep their children safe, and to a lesser extent, shape future outcomes. In this way, working-class parents appear to use structured activities as part of a preventive parenting strategy (i.e., enrolling children in activities to keep them busy, out of the neighborhood, and safe) and as a promotive strategy (i.e., to open doors to future opportunities such as college or career entry) (Furstenberg et al. 1999). The responses of working- and middle-class parents to our structured activity scenario and their articulated reasons for their own children’s activity participation are summarized in Figure 3.x

Figure 3.

Concerns about and reasons for children’s participation in structured activities by social class

Our findings on parents’ practices (i.e., enrollment of children in activities) combine with our findings on their expressed logic to reveal a puzzle—differences in the behavior of working- and middle-class parents, but substantial overlap in their perspectives on activity participation. That is, class differences in behavior do not appear to reflect class differences in parenting logics regarding organized activities. In the next section, we attempt to shed light on the question that has emerged from our data: why do working-class youth demonstrate less participation in structured activities than their middle-class counterparts given similarities in their parents’ perspectives about the value and desirability of participation? The answer, we argue, lies in what our data reveal about the role of structure in class gaps in youth’s participation in organized activities.

SCHOOLS AS EQUALIZING INSTITUTIONS

We draw a distinction between school and out-of-school activities to investigate structural influences on activity participation. We find that a clear majority of the activities in which working-class children participate are school-based activities; more than half (60.0%) of their activities are organizationally tied to the school compared to only 40% of the activities of middle-class youth (not shown). Moreover, the class gap in activity participation is smaller in school activities than in out-of-school activities. Working-class youth participate in an average of 1.5 school activities, which compares favorably to the 2.0 school activities in which middle-class children participate (see Table 1). Where working-class children fall short, and much shorter than their middle-class counterparts, is in participation in out-of-school activities. In these, they participate in less than one activity, on average, compared to 3.0 activities among the middle class.

These findings have at least three implications. First, schools serve as a critical avenue through which the children of working-class families become involved in organized activities. Second, where opportunities for participation are readily available, working-class parents demonstrate an interest in and commitment to supplementing the lives of their children by investing time, energy, and money in their children’s involvement in activities. Finally, without the opportunities for participation that schools provide, the social class gap in activity involvement would likely be much larger than that previously documented.

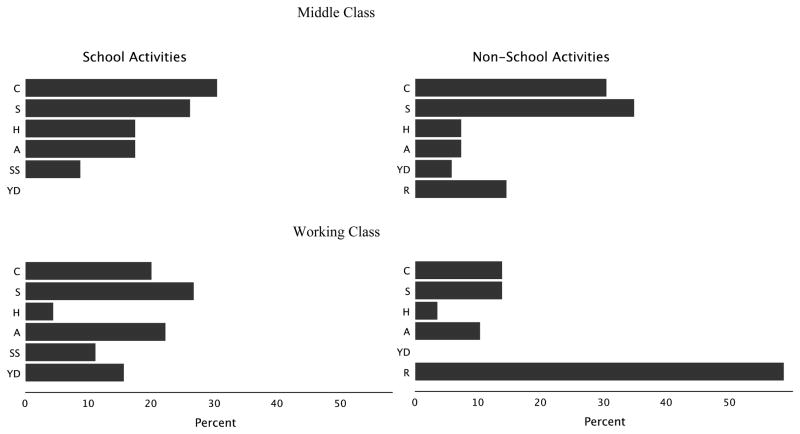

That working- and middle-class children differentially become involved in school versus non-school activities has implications not just for their level of participation, but also for the kinds of activities in which they participate. Figure 4 presents percentage distributions of school and out-of-school activities for working- and middle-class children across activity type. This figure underscores the role schools play in class differences in structured activity participation. The working-class and middle-class distributions for school-based activities are somewhat similar. Both groups display high levels of participation in sports and cultural activities and, to a lesser extent, academic and school-service activities. Middle-class children have greater participation, however, in hobby activities, while having no involvement in youth-development activities. These class differences, however, are rather small compared to those found in out-of-school activities.

Figure 4.

Percentage Distribution of School and Non-School Activities Across Activity Type by Social Class Location.

Note: C=cultural; S=sports; H=hobby; A=academic; SS=school service; YD=youth development; R=religious.

Working- and middle-class families differ strikingly in their non-school activities. Middle-class children display heavy participation in cultural and sports activities, with less participation in academic and hobby activities. Thus, their investments in activities outside of school mirror, to some extent, those they make in school. In contrast, working-class children invest heavily in religious activities, often regular church attendance, church choir, or church youth group. Although these children also participate in cultural, sports, and academic activities outside of school, they do so to a much lower degree than they do in school. Thus, it appears that the decisions that working-class parents and children make about where to invest time, energy, and resources outside of school are rather different than the choices they make about which activities to pursue in school.

The seven types of activities reflected in Figure 4 necessarily mask the heterogeneity that exists within them. But it is the diversity within cultural, academic, and school-service activities across schools, for example, that may also shape class differences in the kinds of activities in which working- and middle-class children participate. Indeed, the activities offered to children through schools are surely structured by the financial and human resources that are available to them. Given this, the range of activities available to children—their activity choice-set—is structured by the schools they attend. The extent to which working-class children attend schools that offer a limited choice-set of activities, particularly compared to the range of activities available at schools attended by middle-class children, may serve as an underlying source of class differences in extracurricular activity participation. It may also have implications for the ways in which organized activities pay off or fail to pay off given connections between activity participation and educational outcomes (Kaufman and Gabler 2004).

Research on the academic consequences of participation in organized activities suggests that certain school-based activities may increase the odds that students will be admitted to college, while other activities may raise their chances of enrolling in selective colleges (Eccles and Barber 1999). Gabler and Kaufman (2006) find, for example, that participation in music, student government, and interscholastic sports are associated with an increased likelihood of attending college, while participation in hobby clubs, school yearbook, and school newspaper increases the chances of attending an elite university. Using these findings as an evaluative lens on the activity choice-set offered at our two schools, we find that the middle-class school offers its students greater opportunities to participate in activities that may pay educational dividends in terms of college attendance and selectivity.

Before reporting on the differences between the two schools, however, we describe their similarities. First, the two schools offer approximately the same number of structured activities (see Table 3). Secondly, there is overlap in the choice-set of activities available to students at the two schools, particularly with regard to sports and school-service activities. Both schools offer students the opportunity to participate in team sports (e.g., flag football, basketball, softball, and volleyball), serve on yearbook committees, publish literary magazines, and work in libraries alongside school librarians. In sum, both schools offer students opportunities to participate in activities that have the potential to pay educational dividends.

Table 3.

Structured Activities Offered by Working-Class and Middle-Class Schools.

| Type of Activity | Working-Class School (N=46) | Middle-Class School (N=38) |

|---|---|---|

| Sports | Golf Cheerleadinga Indoor Soccer Softball Basketballa Tracka Volleyballa Flag Football Net Sports Drill Teama |

Flag Footballa Gymnasticsa Basketballa Tracka Volleyballa |

| Cultural | Dance Cluba Drama Cluba Combined Chorus |

Jazz

Band Orchestra Choir Concert Band Guitar Ensemblea Drum Lessonsa String Orchestra Ink Drinkers Literature Club Musical |

| Academic | Science Cluba Book Club/Books without Bordersa Oratorical Competition 1 Oratorical Competition 2 Words Shook World Odyssey of the Mind Math Club Math Power Hour Reading Tutoring Reading Prep for State Exam Math Homework Club Open Library |

National Academic Leaguea Book Club/Books without Bordersa Biology Tutoring Math Tutorial English Tutoring Science Tutoring Ecology General Science/Biology Homework Club Math “Twenty-Four” Game Science Fair Activities Computer Open Lab Library Extended Day |

| School-Service | Literary

Magazine Yearbook Fundraising Committeea Tutoring (as tutor) a Volunteeringa Library Assistancea Student Computer Technicians Morning Announcement |

Literary Magazine Student Council Eighth Grade Council/Graduation Student Diplomat Yearbook Coordinators Library Assistancea |

| Hobby Club | Model Programa Computer Cluba Sports Club Sewing |

Chess Club Chess Team Run Club |

| Youth Development | Girl Talk Youth Developmenta |

Girl’s Circle Project Teens |

| Other, Unclassified | Fast Forward 24 Club IRAP (Internet Res. & Pub.) 8th Grade Sponsor Amigos de Clemente Day Generation Next |

Reported by respondent, but not by the school.

However, there are meaningful differences in the range of activities available at the two schools. In particular, they offer somewhat different academic and markedly different hobby and cultural activities, which may have implications for the educational trajectories of students. The most notable differences between the two schools reside in hobby and cultural activities. Although the working-class school offers a greater variety of hobby activities, the qualitative differences between them and those offered by the middle-class school are substantial. In one hobby activity, chess, the middle-class school is rather unique in that it offers its students expert-level instruction such that its team is able to compete nationally. There are no expert-level hobby activities at the working-class school. Moreover, the middle-class school offers a number of cultural activities that research suggests may serve as credentials that boost students’ chances of attending college by signaling to teachers and college admissions officers that students either come from middle-class backgrounds or have cultural tastes that are associated with the middle class. Activities such as jazz band, orchestra, choir and concert band are just such activities; yet, they are only offered at the middle-class school. According to data obtained from the list of activities on the website of the working-class school, students there can participate in only one cultural activity—the school chorus—though parents indicate that Drama Club and Dance Club are options. Were they interested in participating in other kinds of cultural activities in order to acquire cultural capital, they must do so outside of school and with, no doubt, greater financial and time investments than would be required were these activities offered at their school.

These findings illustrate that schools can serve as both levelers of class differences in structured activity participation, as well as contributors to such differences.xi With respect to the types of activities in which children become involved, schools may contribute to class differences by offering to students qualitatively different activities even when they offer the same number of activities. However, regarding level of participation, the schools in our data clearly serve to reduce class gaps in participation. Consequently, we are left with the question of what undergirds class differences in out-of-school activities.

FINANCIAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS ON NON-SCHOOL ACTIVITIES AMONG THE WORKING CLASS

At least two possible explanations for social class gaps in non-school activities emerge from our interview data: (1) fewer financial resources in working- versus middle-class families and (2) weaker institutional capacity in working- versus middle-class neighborhoods. A classification of activities that emerged from the data (in contrast to the literature) suggests three groups of non-school activities: elite activities, (non-elite) religious activities, and (non-elite) secular activities. Elite activities are ones often discussed in the literature as those that provide cultural capital to youth, as well as provide them with educational benefits like increased odds of attending college. They include activities such as chess, music and dance lessons, summer programs at selective universities and other institutions. Religious activities are as we have previously defined them—those that are offered by religious institutions, such as church youth groups. Secular activities are non-elite activities that are unaffiliated with religious institutions or organizations, such as sports in community leagues. This categorization of non-school activities makes it strikingly clear just how different working- and middle-class children are in their out-of-school activities (see Figure 5). While middle-class children are involved in 4.3 times as many non-elite secular activities as working-class youth, they participate in 20 times as many elite activities relative to their working-class peers.xii We suggest that class differences in financial resources undergird gaps in participation in elite activities, while the scarcity of secular institutions devoted to youth programs in working-class neighborhoods may undergird class gaps in secular activities.

Figure 5.

Percentage distribution of non-school activities across elite, (non-elite) secular, and (non-elite) religious activities by social class location.

Note: E=elite; S=(non-elite) secular; R=(non-elite) religious.

Participation in elite activities often requires sizeable financial investments. Our middle-class respondents report spending $400 a year on foreign language classes, $300–$1,080 a year on music lessons, $90–$3,337 a year on dance lessons, and $2,600–$12,500 per year on chess lessons and competitions. Such financial commitments are possible for a group of parents that command substantial financial resources. The relevance of financial capital to participation is further illustrated by examining differences between upper-middle- and lower-middle-class families.xiii Families that earn more than $75,000 annually participate in 2.6 times as many elite activities as middle-class families that earn less. No doubt, then, that participation in elite activities is more difficult for families with even more modest incomes.

Certainly, there are cases in which working-class youth are able to gain access to elite activities, such as when students obtain scholarships. Kenneth, for example, is a talented emerging artist whose mother has in the past been able to secure scholarships for art classes at a local art college where the instructors are professional artists. Other working-class children are able to attend private and university-based summer programs through scholarships. However, these represent exceptional experiences among the working class.

Indeed, the financial realities of working-class families are made clear by their responses to our question as to whether they had ever been prevented from doing something for their child because of financial limitations. Some working-class parents explicitly identify limits on their children’s participation in activities. For example, Anne, a working-class black mother who is a caseworker indicates that she was unable to send her daughter to a summer program at an elite university because of financial limitations. She states:

A lot of kids are going to summer programs. I know [an out-of-state elite university] had asked and there’s a camp for gifted youth or something like [that], and had tried to get her to participate. I didn’t have the money. I would have liked her to go, but it was out and it was just outrageous. Even now, I think that there are a couple of summer programs that, there was a science camp that I wanted to send her to and it was just, and I just couldn’t do it. So in that regard, I would say, yeah. You know, there’s a lot of things I wish I could have been able to do.

The cost of the summer camp would have been approximately $3500 or more, depending on programming and book fees.

Although Anne makes a connection between financial constraints and her daughter’s participation in activities, relatively few working-class parents did when asked whether and how financial limitations had prevented them from doing something for their child. Perhaps the reason is because they often mentioned more basic elements in the hierarchy of human needs like food, bills, basic school supplies, without addressing the less “prepotent” needs of belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization that one associates with structured activities (Maslow 1943: 394). For example, Gabriela, a working-class Latina mother who works as a hotel housekeeper, describes why her son must get by with only two sets of school uniforms instead of the five she would like to buy for him:

I’m not gonna, gonna go to buy the two changes of clothes until the first [of the month], with what I earned Saturday and Monday. …I’ve left it ‘til the last minute, because it’s too much, too much. Since I pay $1,600 in rent plus electric, gas, phone, we’re talking about $2,100. God willing, next year…I’ll be able to give him the luxury of buying him the five pants, (chuckle), the five shirts, but not this year. They’re going to have to deal; wash and wear (translated from Spanish).

Other parents (as well as Gabriela) further indicate that financial constraints had prevented them from providing their children with educational opportunities they felt were important, such as attendance at private/Catholic school, home computers, and savings for college.

Middle-class parents also indicate that they had been prevented from doing something for their children because of financial constraints. Slightly more than half of them felt that way, some of whom explicitly mentioned limits on activities (in particular summer programs abroad and at elite universities), but also travel to learn a foreign language, private school attendance, vacations, and savings for college. However, it is worth noting that the tone of the conversation with middle-class parents was substantially different on this topic than was that of working-class parents in that no middle-class parent cited a basic need as something their child has foregone because of financial constraints.

Middle-class children’s enrollment patterns in non-elite secular activities, especially in contrast to their working-class counterparts, implicates the community as a second possible source of class differences in participation in out-of-school activities. If disadvantaged neighborhoods contain fewer institutions and community-based organizations than middle-class areas, then the community emerges as a source of stratification with respect to structured activity enrollment. We have already seen that working-class parents rely more heavily than their middle-class counterparts on schools to provide opportunities for their children’s involvement in activities. This finding, along with that of their heavy participation in religious activities outside of school, suggests a broader reliance upon public social institutions for activity participation, particularly given their financial constraints on participation in elite activities. Indeed, the majority of non-elite secular activities that middle-class parents report their children were involved in (organized sports) are ones tied to community organizations (i.e., sports leagues). Yet, only two working-class children in our sample are involved in organized sports outside of school. We suspect the lack of involvement in such activities is not necessarily reflective of the interests of working-class youth, particularly given their level of involvement in sports at school, but rather the absence of organizations devoted to the interests of youth in working-class neighborhoods. This means that activities tied to religious institutions may substitute for some of the non-elite secular activities they might opt to participate in were they available in their neighborhoods, as well as for some of the elite activities that working-class parents find cost-prohibitive.

Indeed, the literature on neighborhood organization and its relationship to youth development describes the relative absence of effective neighborhood institutions in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods (Wilson 1987, 1996; Quane and Rankin 2006). With respect to organizations that provide opportunities for activity participation, Elliot et al. (2006) note that

… institutions that provide recreational and supportive educational services to youth—YMCAs, Big Brothers Big Sisters, Little Leagues and other recreational programs, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, Boys and Girls Clubs—are less likely to be found in disadvantaged neighborhoods and those that are located in these neighborhoods typically have fewer resources than those in more affluent neighborhoods. (P. 107)