Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with increased risk for CRC. A molecular understanding of the functional consequences of this genetic variation has been complicated because each GWAS SNP is a surrogate for hundreds of other SNPs, most of which are located in non-coding regions. Here we use genomic and epigenomic information to test the hypothesis that the GWAS SNPs and/or correlated SNPs are in elements that regulate gene expression, and identify 23 promoters and 28 enhancers. Using gene expression data from normal and tumour cells, we identify 66 putative target genes of the risk-associated enhancers (10 of which were also identified by promoter SNPs). Employing CRISPR nucleases, we delete one risk-associated enhancer and identify genes showing altered expression. We suggest that similar studies be performed to characterize all CRC risk-associated enhancers.

Previous studies identified genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer (CRC), but the functional consequences of these genetic risk factors remain poorly understood. Here, the authors report that CRC risk variants reside in promoters and enhancers and could increase colon cancer risk through gene expression regulation.

Previous studies identified genetic variants associated with colorectal cancer (CRC), but the functional consequences of these genetic risk factors remain poorly understood. Here, the authors report that CRC risk variants reside in promoters and enhancers and could increase colon cancer risk through gene expression regulation.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States. The incidence of death from CRC is in the top 3 of all cancers in the United States for both men and women ( http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/toptencancers.aspx). It is estimated that 142,820 men and women will be diagnosed with, and 50,830 men and women will die of, cancer of the colon and rectum in 2013 ( http://seer.cancer.gov/-statfacts/html/colorect.html). A better understanding of the regulatory factors and signalling pathways that are deregulated in CRC could provide new insights into appropriate chemotherapeutic targets. Decades of studies have revealed that certain genes and pathways, such as WNT, RAS, PI3K, TGF-B, p53 and mismatch repair proteins, are important in the initiation and progression of CRC1. In an attempt to obtain a more comprehensive view of CRC, two new approaches have been used: exome sequencing of tumours and genome-wide population analyses of human variation. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has taken the first of these new approaches in the hopes of moving closer to a full molecular characterization of the genetic contributions to CRC, analyzing somatic alterations in 224 tumours2. These studies again implicated the WNT, RAS and PI3K signalling pathways. The second new approach identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with specific diseases using genome-wide association studies (GWAS). GWAS has led to the identification of thousands of SNPs associated with a large number of phenotypes3,4. Such studies identify what are known as tag SNPs that are associated with a particular disease. Specifically for CRC, 25–30 tag SNPs have been identified5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12.

Although identification of tag SNPs is an important first step in understanding the relationship between human variation and risk for CRC, a major challenge in the post-GWAS era is to understand the functional significance of the identified SNPs13. It is critical to advance the field by progressing from a statistical association between genetic variation and disease to a molecular understanding of the functional consequences of the genetic variation. Progress towards this goal has been mostly successful when the genetic variation falls within a coding region. Unfortunately, most SNPs identified as associated with human disease in large GWAS studies are located within large introns or distal to coding regions, in what in the past has been considered to be the unexplored territory of the genome. However, recent studies from the ENCODE Consortium have shown that introns and regions distal to genes contain regulatory elements. In particular, the ENCODE Consortium has made major progress in defining hundreds of thousands of cell-type-specific distal enhancer regions14,15,16. Comparison of GWAS SNPs to these enhancer regions has revealed several important findings. For example, work from ENCODE and others13,15,17,18 have shown that many GWAS SNPs fall within enhancers, DNase hypersensitive sites and transcription factor binding sites. It is also clear that the SNP whose functional role is most strongly supported by ENCODE data is often a SNP in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the GWAS tag SNP, not the actual SNP reported in the association study19.

These recent reports clearly show that regulatory elements can help to identify important SNPs13,19,20. However, the studies were performed using all available ENCODE data and did not focus the functional analysis of cancer-associated SNPs on the regulatory information obtained using the relevant cell types. Using epigenetic marks obtained from normal colon and colon cancer cells, we identify SNPs in high LD with GWAS SNPs that are located in regulatory elements specifically active in normal and/or tumour colon cells. Characterization of transcripts nearby CRC risk-associated promoters and enhancers using RNA expression data allows the prediction of putative genes and non-coding RNAs associated with an increased risk of colon cancer. Using genomic nucleases, we delete one risk-associated enhancer and compare the deregulated genes with those predicted to be targets of that enhancer. Our studies suggest that transcriptome characterization after precise deletion of a risk-associated enhancer could be a useful approach for post-GWAS analyses.

Results

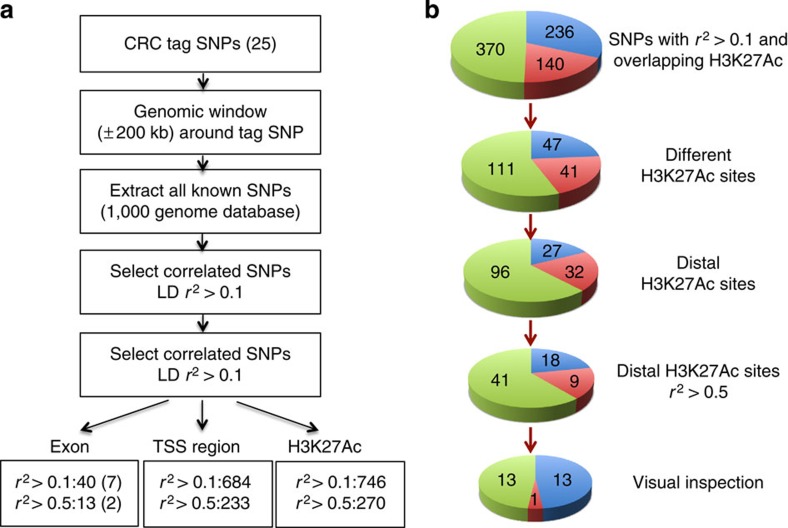

CRC risk-associated SNPs linked to a specific gene

For our studies, we chose 25 tag SNPs, 4 of which have been associated with an increased risk for CRC in Asia-derived case-control cohorts and the rest in Europe-derived case-control cohorts; the genomic coordinates of each SNP can be found in Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1. Of these 25 tag SNPs, only one is found within an exon, occurring in the third exon of the MYNN gene and resulting in a synonymous change that does not lead to a coding difference. However, there are hundreds of SNPs in high LD with each tag SNP and it is possible that some of the high LD SNPs may reside in coding exons. To address this possibility we used a bioinformatics programme called FunciSNP to identify SNPs correlated with CRC tag SNPs that also intersect the set of coding exons in the human genome21. FunciSNP is an R/Bioconductor package that allows a comparison of population-based correlated SNPs from the 1,000 Genomes Project ( http://www.1000genomes.org/) with any set of chromatin biofeatures. In this initial analysis, we chose coding exons from the Gencode 15 data set ( http://www.gencodegenes.org/releases/) as the biofeature. Because LD varies with the population, to identify population-based correlated SNPs we specified the Asian population for analysis of the four tag SNPs identified using Asian-derived case-control cohorts and we specified the European population for analysis of the rest of the tag SNPs. Using FunciSNP, we identified 240 unique SNPs that are correlated with the 25 tag SNPs at an r2>0.1 and are within a coding exon (Supplementary Fig. 1). We then used snpeff ( http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/ (ref. 22)) to determine that 40 of these correlated SNPs create non-synonymous changes; however, limiting the SNPs to those with an LD of r2>0.5 with the tag SNP reduced the number to only 13. Using polyphen-2 ( http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/ (ref. 23)) and provean ( http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php (ref. 24)), only two potentially damaging SNPs at r2>0.5 were found, both in POU5F1B (Fig. 1). At the less restrictive r2>0.1, four other genes were also found to harbour a damaging SNP (RHPN2, UTP23, LAMA5 and FAM186A). To determine if these genes are expressed in colon cells, we performed two replicates of RNA-seq for HCT116 cells and also used RNA-seq data from the Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Consortium for normal sigmoid colon to examine expression. After analysis of both sets of RNA-seq data, we categorized transcripts that are not expressed as having <0.5 FPKM (expected fragments per kilobase of transcripts per million fragments sequenced) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Analysis of the RNA-seq data revealed that POU5F1B and FAM186A are not expressed in either the normal sigmoid colon or HCT116 cells (however, these genes are expressed in a cohort of TCGA colon tumours; see Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of regions linked to CRC tag SNPs.

Figure 1. Identification of potential functional SNPs for CRC.

(a) Shown is the number of SNPs identified by FunciSNP in each of three categories for 25 colon cancer risk loci (see Table 1 for information on each CRC risk SNP). For exons, only non-synonymous SNPs are reported; parentheses indicated the number of SNPs that are predicted to be damaging; see Table 2 for a list of the expressed genes associated with the correlated SNPs. For TSS regions, the region from −2 kb to +2 kb relative to the start site of all transcripts annotated in GENCODE V15, including coding genes and non-coding RNAs was used; see Table 2 for a list of expressed transcripts associated with the correlated SNPs. (b) For H3K27Ac analyses, ChIP-seq data from normal sigmoid colon and HCT116 tumour cells were used; see Table 3 for further analysis of distal regions harbouring SNPs in normal and tumour colon cells. The SNPs having an r2>0.1 that overlapped with H3K27Ac sites were identified separately for HCT116 and sigmoid colon data sets. Because more than one SNPs could identify the same H3K27Ac-marked region, the SNPs were then collapsed into distinct H3K27Ac peaks. The sites that were within ±2 kb of a promoter region were removed to limit the analysis to distal elements. To obtain a more stringent set of enhancers, those regions having only SNPs with r2<0.5 were removed. This remaining set of 68 distal H3K27Ac sites were contained within 19 of the 25 risk loci. Visual inspection to identify only the robust enhancers having linked SNPs not at the margins reduced the set to 27 enhancers located in 9 of the 25 risk loci; an additional enhancer was identified in SW480 cells (see Table 3 for the genomic locations of all 28 enhancers). Colour key: green=SNPs or H3K27Ac sites unique to normal colon, red=unique to colon tumour cells, blue=present in both normal and tumour colon.

Table 2. Expressed transcripts directly linked to CRC tag SNPs.

| Tag SNP | Exons | RNAs of TSS SNPs |

|---|---|---|

| rs10936599 | ACTRT3, MYNN, (TERC) | |

| rs1321311 | CDKN1A | |

| rs16892766 | UTP23 | EIF3H |

| rs7014346 | (RP11-382A18.1) | |

| rs3824999 | POLD3 | |

| rs3802842 | C11orf92, C11orf93, C11orf53 | |

| rs7136702 | DIP2B | |

| rs11169552 | ATF1, DIP2B | |

| rs4444235 | BMP4 | |

| rs4779584 | GREM1 | |

| rs9929218 | CDH3, CDH1 | |

| rs10411210 | RHPN2 | GPATCH1, RHPN2 |

| rs4925386 | LAMA5 | LAMA5 |

CRC, colorectal cancer; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TSS, transcription start site.

Only three damaging SNPs having an r2>0.1 were identified in the exons of genes expressed in either HCT116 or normal sigmoid colon cells; of these, only UTP23 and RHPN2 were identified as damaging by two different programmes. RNAs expressed in HCT116 or sigmoid colon cells and having a correlated SNP with r2>0.5 within ±2 kb of the TSS of protein-coding transcripts or non-coding RNAs are shown. The cases in which the tag SNP is located in the TSS region are in bold and non-coding RNAs are in parentheses. We note that exon SNPs identified two additional expressed genes (POU5F1B and FAM186A) and promoter SNPs identified three additional expressed genes (FAM186A, LRRC34 and LRRIQ4) when a larger number of TCGA colon tumour samples were analyzed.

Another way to link a SNP to particular gene is if the SNP falls within a promoter region. We again used FunciSNP, but this time the biofeature analyzed corresponded to the region from −2,000 to +2,000 nucleotides of the transcription start site (TSS) of each transcribed gene (we analyzed coding and non-coding transcripts from GENCODE V15). We chose to include 2 kb upstream and downstream of the start site as the promoter-proximal regions because several studies25,26, as well as visual inspection of the ENCODE TF Chromatin Immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) tracks, have shown that transcription factors can bind on either side of a TSS. Using an r2>0.1, we found 684 correlated promoter SNPs which were reduced to 233 SNPs at r2>0.5 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Many of these SNPs fall within the same promoter regions. When collapsed into distinct promoters, we identified the TSS regions of 17 protein-coding genes and 2 non-coding RNAs which are expressed in HCT116 or sigmoid colon cells; promoter SNPs identified 4 additional expressed genes when a larger number of TCGA colon tumour samples were analyzed (Table 2).

CRC risk-associated SNPs in distal regulatory regions

Most of the SNPs in LD with the CRC GWAS tag SNPs cannot be easily linked to a specific gene because they do not fall within a coding region or a promoter-proximal region. However, it is possible that a relevant SNP associated with increased risk lies within a distal regulatory element of a gene whose function is important in cell growth or tumorigenicity. To address this possibility, we used the histone modification H3K27Ac to identify active regulatory regions throughout the genome of colon cancer cells or normal sigmoid colon cells. We used HCT116 H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data16 produced in our lab for the tumour cells and we obtained H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data for normal colon cells from the NIH Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Consortium. The ChIP-seq data for both the normal and tumour cells included two replicates. To demonstrate the high quality of the data sets, we called peaks on each replicate of H3K27Ac from HCT116 and each replicate of H3K27Ac from sigmoid colon using Sole-search27,28 and compared the peak sets from the two replicates using the ENCODE 40% overlap rule (after truncating both lists to the same number, 80% of the top 40% of one replicate must be found in the other replicate and vice versa). After determining that the HCT116 and sigmoid colon data sets were of high quality (Supplementary Fig. 4), we merged the two replicates from HCT116 and separately merged the two replicates from sigmoid colon and called peaks on the two merged data sets; see Supplementary Data 2 for a list of all ChIP-seq peaks. Using the merged peak lists from each of the samples as biofeatures in FunciSNP, we determined that 746 of the 4,894 SNPs that were in LD with a tag SNP at r2>0.1 were located in H3K27Ac regions identified in either the HCT116 or sigmoid colon peak sets; of these 270 SNPs had an r2>0.5 with a tag SNP (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

A comparison of the H3K27Ac peaks from normal and tumour cells indicated that the patterns are very similar; in fact, ~24,000 H3K27Ac peaks are in common in the normal and tumour cells. However, there are clearly some peaks unique to normal and some peaks unique to the tumour cells. Therefore, we separately analyzed the normal and tumour H3K27Ac ChIP-seq peaks as different sets of biofeatures using FunciSNP (Fig. 1b). Of the 746 SNPs, 236 were located in a H3K27Ac site common to both normal and tumour cells, whereas 140 were unique to tumour and 370 were unique to normal cells. Visual inspection of the SNPs and peaks using the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser showed that many of the identified enhancers harboured multiple correlated SNPs. Reduction of the number of SNPs to the number of different H3K27Ac sites resulted in 47 common, 41 tumour-specific and 111 normal-specific regions. Visual inspection also showed that some of the H3K27 genomic regions corresponded to promoter regions (Supplementary Fig. 4). Because promoter regions having correlated SNPs were already identified using TSS regions (see above), we eliminated the promoter-proximal H3K27Ac sites, resulting in 27 common, 32 tumour-specific and 96 normal-specific distal H3K27Ac regions. As the next winnowing step, we selected only those enhancers having at least one SNP with an r2>0.5, leaving 18 common, 9 tumour-specific and 41 normal-specific distal H3K27Ac regions. We noted that some of the identified regions corresponded to low-ranked H3K27Ac peaks. For our subsequent analyses, we wanted to limit our studies to robust enhancers that harbour correlated SNPs. Therefore, we visually inspected each of the genomic regions identified as having distal H3K27Ac peaks harbouring a correlated SNP. To prioritize the distal regions for further analysis, we eliminated those for which the correlated SNPs was on the edge of the region covered by the H3K27Ac signal or corresponded to a very low-ranked peak. After inspection, we were left with a set of 27 distal H3K2Ac regions in which a correlated SNP (r2>0.5) was well within the boundaries of a robust peak (Fig. 1b). To confirm our results, we repeated the analysis using H3K27Ac data from a different colon cancer cell line, SW480, identifying only one additional enhancer harbouring risk SNPs for CRC. The genomic coordinates of each of these 28 enhancers, which are clustered in nine genomic regions, are listed in Table 3 (see also Supplementary Table 1). Combining all data, enhancers in five of the nine regions were identified in all three cell types and eight of the nine regions were identified in at least two of the cell types.

Table 3. Distal regulatory regions correlated with CRC tag SNPs.

| Enhancer | Tag SNP | No. of correlated SNPs | Chromosome | Start | End | Location | Nearby expressed coding and non-coding RNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs647161.ASN | 4 | chr5 | 134468409 | 134473214 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | PITX1, CATSPER3, H2AFY |

| 2 | rs647161.ASN | 6 | chr5 | 134474759 | 134478528 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | PITX1, CATSPER3, H2AFY |

| 3* | rs647161.ASN | 4 | chr5 | 134520309 | 134523373 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | PITX1, CATSPER3, H2AFY |

| 4 | rs647161.ASN | 7 | chr5 | 134525698 | 134531612 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | PITX1, CATSPER3, H2AFY |

| 5 | rs647161.ASN | 7 | chr5 | 134543144 | 134548023 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | H2AFY,PITX1 |

| 6 | rs647161.ASN | 7 | chr5 | 134511610 | 134516426 | CTC-203F4.1 intron | PITX1,CATSPER3,H2AFY |

| 7 | rs10505477, rs6983267, rs7014346 | 3 | chr8 | 128412778 | 128414859 | RP11-382A18.1 intron | MYC, RP11-382A18.1, RP11-382A18.2, RP11-255B23.3 |

| 8* | rs10505477, rs6983267, rs7014346 | 5 | chr8 | 128420412 | 128422114 | RP11-382A18.1 intron | MYC, RP11-382A18.1, RP11-382A18.2, RP11-255B23.3 |

| 9* | rs3824999 | 4 | chr11 | 74288844 | 74294943 | Intergenic | POLD3, LIPT2, KCNE3, AP001372.2 |

| 10 | rs10774214.ASN | 1 | chr12 | 4378128 | 4379840 | Intergenic | CCND2, C12orf5 |

| 11* | rs7136702 | 1 | chr12 | 50908239 | 50913757 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, LARP4 |

| 12 | rs7136702 | 2 | chr12 | 50938468 | 50940796 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, LARP4 |

| 13* | rs7136702 | 2 | chr12 | 51018019 | 51020503 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, ATF1, LARP4 |

| 14* | rs11169552 | 1 | chr12 | 50973150 | 50974328 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, LARP4 |

| 15 | rs11169552 | 1 | chr12 | 51012054 | 51014942 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, ATF1, LARP4 |

| 16 | rs11169552, rs7136702 | 3 | chr12 | 51040371 | 51042207 | DIP2B intron | DIP2B, ATF1 |

| 17 | rs9929218 | 1 | chr16 | 68740822 | 68742561 | Intergenic | CDH3, CDH1, TMCO7 |

| 18* | rs9929218 | 4 | chr16 | 68754658 | 68757192 | Intergenic | CDH1, CDH3, TMCO7 |

| 19 | rs9929218 | 5 | chr16 | 68774214 | 68780161 | CDH1 intron | CDH1, CDH3, TMCO7 |

| 20 | rs9929218 | 11 | chr16 | 68784044 | 68791839 | CDH1 intron | CDH1, CDH3, TMCO7 |

| 21 | rs4939827 | 4 | chr18 | 46448530 | 46450772 | SMAD7 intron | SMAD7, CTIF, DYM, RP11-15F12.1 |

| 22 | rs4939827 | 6 | chr18 | 46450800 | 46454601 | SMAD7 intron | SMAD7, CTIF, DYM, RP11-15F12.1 |

| 23 | rs10411210 | 6 | chr19 | 33537339 | 33541195 | RHPN2 intron | RHPN2, GPATCH1, C19orf40 |

| 24 | rs10411210 | 1 | Chr19 | 33530860 | 33533823 | RHPN2 intron | RHPN2, GPATCH1, C19orf40 |

| 25 | rs4925386 | 3 | chr20 | 60929861 | 60935447 | LAMA5 intron | LAMA5, RPS21, CABLES2, RP11-157P1.4 |

| 26 | rs4925386 | 3 | chr20 | 60938278 | 60941762 | LAMA5 intron | LAMA5, RPS21, CABLES2, RP11-157P1.4 |

| 27 | rs4925386 | 6 | chr20 | 60948726 | 60951918 | Intergenic | LAMA5, RPS21, CABLES2 |

| 28 | rs4925386 | 6 | chr20 | 60955085 | 60958391 | Intergenic | RPS21, LAMA5, CABLES2 |

CRC, colorectal cancer; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

The tag SNP and the correlated SNPs for 28 distal, robust H3K27Ac regions are indicated; the enhancers that are found only in normal sigmoid colon are indicated with an asterisk. The three nearest protein-coding RNAs and three nearest non-coding RNAs were identified using the GENCODE V15 gene annotation; only those RNAs that are expressed in HCT116 or sigmoid colon cells are shown (see also Supplementary Table 1).

Effects of SNPs on binding motifs in the distal elements

To determine possible effects of the correlated SNPs on transcription factor binding, we first analyzed all SNPs having an r2>0.1 with the 25 CRC tag SNPs. Using position weight matrices from Factorbook29, all correlated SNPs that fell within a critical position in a transcription factor binding motif were identified (Supplementary Data 3). We identified ~800 SNPs that were predicted to impact binding of transcription factor to a known motif. However, most of these SNPs are not in regulatory regions important for CRC. Therefore, we next limited our analysis to the set of correlated SNPs that fall within the 28 robust enhancers (Supplementary Table 2). We found 80 SNPs that cause motif changes in a total of 124 motifs, representing binding sites for 40 different transcription factors. Using RNA-seq data, we found that 36 of these factors are expressed in HCT116 and/or sigmoid colon cells (Table 4), suggesting that perhaps the binding of these factors at the risk-associated enhancers is influenced by the correlated SNPs. Of the 36 factors, most were expressed at either approximately the same levels in normal and tumour colon or at higher levels in HCT116 cells than in normal colon. However, several factors showed large decreases in gene expression in HCT116 as compared with sigmoid colon cells, including FOS and JUN which were ~10-fold higher in normal colon and HNF4A and ETS1 which were 30–40-fold higher in normal colon; Supplementary Table 3.

Table 4. Effects of SNPs on motifs in the distal regulatory regions.

| AP1 | EGR1 | MYC/MAX | TCF12 |

| AP2 | ELF1 | NR2C2 | TCF7L2 |

| BHLHE40 | ELK4 | PBX3* | TEAD1 |

| CEBPB | ESRRA | PRDM1 | THAP1† |

| CREB1 | ETS1 | RUNX1 | USF1 |

| CTCF | GABP | RXRA | YY1 |

| E2F1 | GATA | SP1 | ZBTB7A‡ |

| E2F4 | GFI1 | SREBF1 | ZEB1 |

| EBF1 | HNF4A | STAT1 | ZNF281 |

ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Details concerning the impacted motifs (SNP position, sequence of reference and alternative alleles, and the direction of the effect on the motif) can be found in Supplementary Data 3.

*Identified by motif UA2, which was the top motif in PBX3 GM12878 ChIP-seq data.

†Identified by motif UA5.

‡Identified by motif UA3, which was the top motif in ZBTB7A K562 ChIP-seq data.

Expression analysis of candidate risk-associated genes

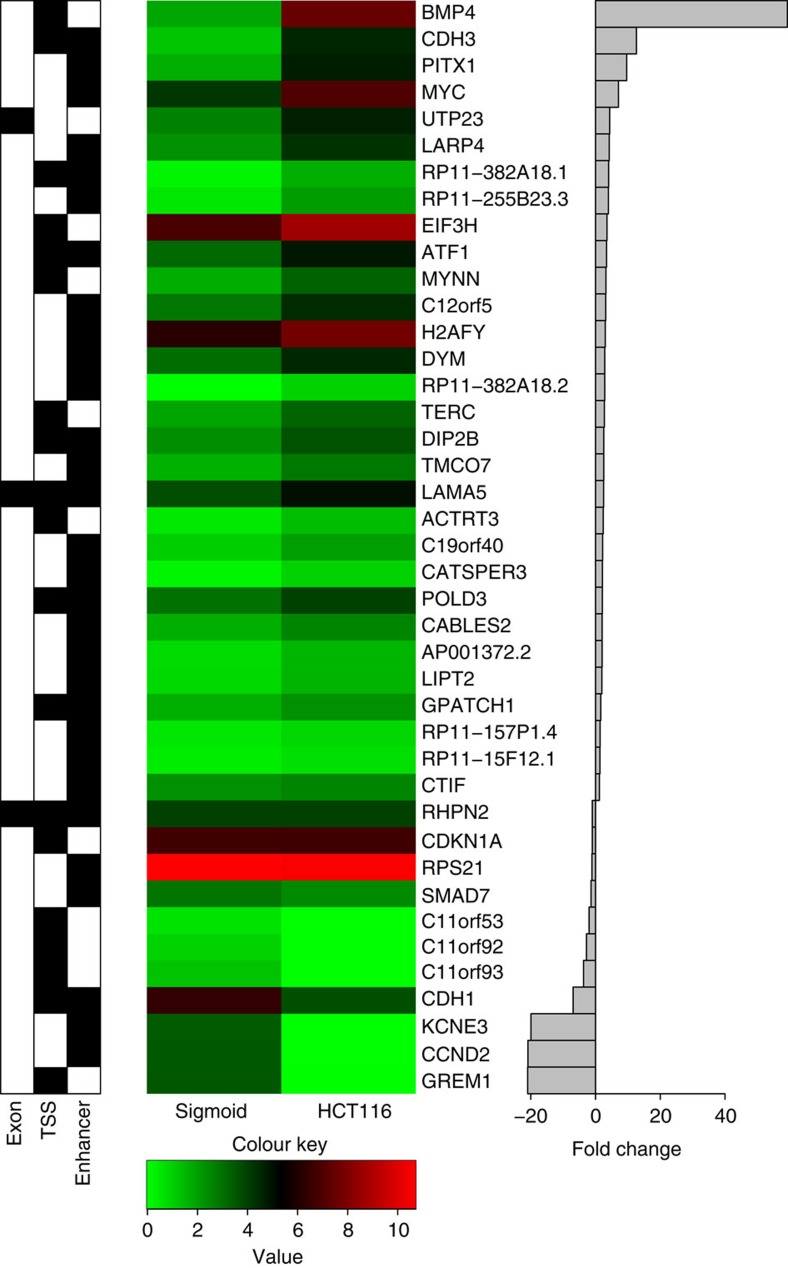

Although the genes identified by the exon or TSS SNPs are clearly good candidate genes for analysis of their possible role in the development of colon cancer, it is difficult to definitively link a target gene with a distal enhancer region because enhancers can function in either direction and do not necessarily regulate the nearest gene. In fact, the ENCODE Consortium recently reported that, on an average, a distal element can physically associate with approximately three different promoter regions30. Also, only 27% of the distal elements showed an interaction with the nearest TSS, although this increased to 47% when only expressed genes were used in the analysis30. Taken together, these analyses suggest that examining the three nearest genes may produce a reasonable list of genes potentially regulated by the CRC risk-associated enhancers. Therefore, we used the GENCODE V15 data set and identified the three nearest promoters of coding genes and three nearest promoters of non-coding transcripts around each of the 28 enhancers (Supplementary Table 1). We next limited the nearby coding and non-coding transcripts to those expressed in either sigmoid colon RNA or HCT116 cells (Table 3); we note that taking into account expression did not greatly change the list of coding transcripts but eliminated most of the non-coding transcripts, which tend to be expressed in a very cell-type-specific manner. Interestingly, several of the genes nearby the risk-associated enhancers were also identified in the TSS analyses, suggesting that a putative causal gene associated with CRC might be differentially regulated by risk-associated SNPs found in the promoter and in a nearby enhancer (Fig. 2). We note that in these cases, the promoters and enhancers were identified by different risk-associated SNPs in high LD with a tag SNP, with the promoters being identified by SNPs within ±2 kb of the TSS and enhancers being identified by distal SNPs. We further analyzed the expression levels of all genes directly linked to the risk SNPs (by exons or TSS) and the expressed genes nearby the risk-associated enhancers in normal colon and HCT116 tumour cells. Shown in Fig. 2 are the expression levels of each of the 41 transcripts and the fold change in expression in HCT116 versus normal cells; several of these genes display robust changes in expression in the tumour cells.

Figure 2. Expression of risk-associated genes in colon cells.

The left panel indicates if a transcript was identified by a SNP located in an exon or a TSS or is nearby a risk-associated enhancer; the middle panel shows the expression values of each of the 41 transcripts in sigmoid colon or HCT116 tumour cells; the right panel shows the fold change of each transcript in the tumour cells (positive indicates higher expression in the tumour).

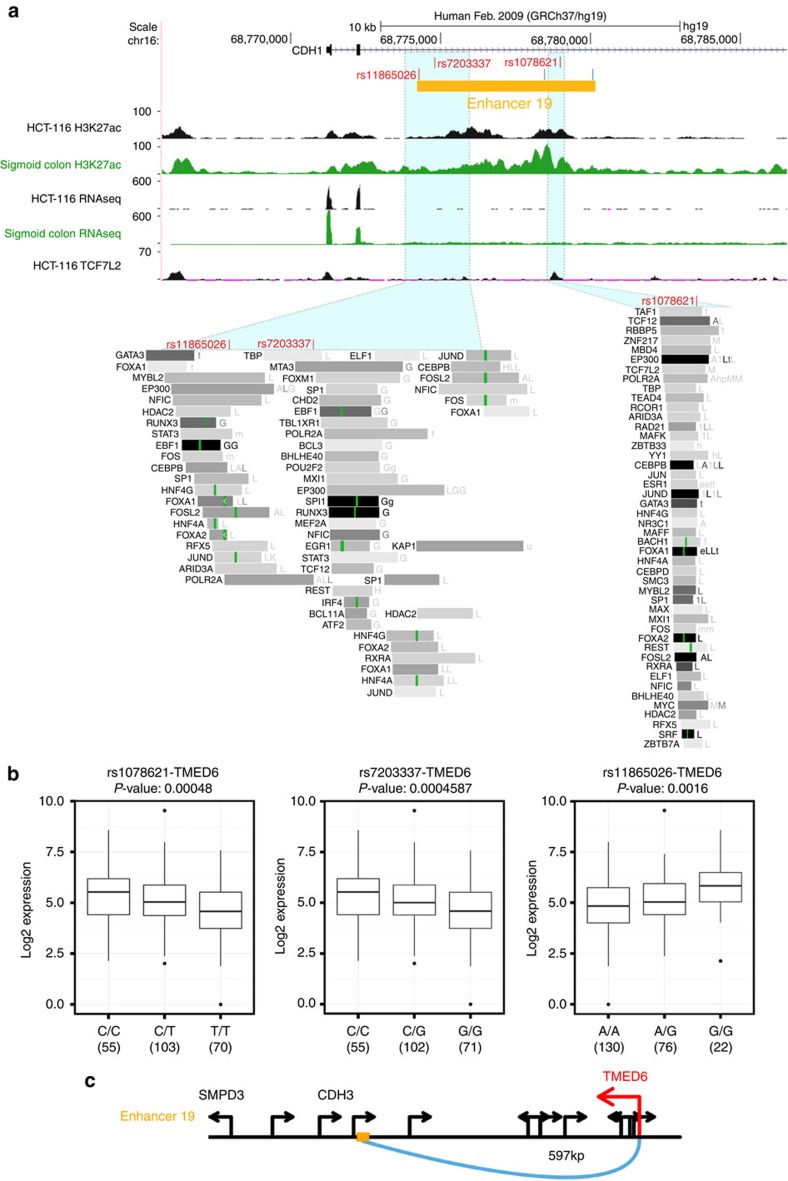

As a second approach to identify transcripts potentially regulated by the identified enhancers, we developed a new statistical approach that employs RNA-seq data from TCGA. We selected the 10 nearest genes 5′ of and the 10 nearest genes 3′ of each of the 28 enhancers. Because of the difference in gene density in different regions of the genome, the 20-gene span ranged from 786 kb to 7.5 MB, depending on the specific enhancer. Because several of the 28 enhancers are clustered near each other, this resulted in a total of 182 unique genes. We downloaded the RNA-seq data for 233 colorectal tumour samples and 21 colorectal normal samples from the TCGA data download website ( https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/dataAccessMatrix.htm) and determined if any of the 182 genes show a significant increase or decrease (greater than twofold change and P-value <0.01) in colon tumours versus normal colon (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 6 for an analysis of potential TCGA batch effects). We then eliminated those genes whose expression change did not correspond to the nature of the enhancer (for example, a tumour-specific enhancer should not regulate a gene that is higher in normal cells), leaving a total of 39 possible genes whose expression might be differentially regulated in colon cancer by the risk enhancers (Table 5). We note that five of the genes shown to be differentially expressed in the TCGA data (MYC, PITX1, POU5F1B, C5orf20 and CDH3) are also in the set of the nearest three genes to an enhancer having CRC risk-associated SNPs. We found that 0–6 differentially expressed genes were linked to an enhancer using the TCGA data, with an average of 4 transcripts per enhancer that showed correct differential expression in colon tumours. Heatmaps of the expression of the 39 putative enhancer-regulated genes, as well as the expression of the genes identified by exon and promoter SNPs, in the TCGA samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. To determine if we could validate any of the putative enhancer targets, we used expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analyses based on data from TCGA. We began by identifying the SNPs within each of the 28 enhancers that are on the Illumina WG SNP6 array used by TCGA. Unfortunately, these arrays include only 8% of the SNPs of interest (that is, the exon, promoter and enhancer SNPs that are correlated with the CRC tag SNPs), greatly limiting our ability to effectively utilize the eQTL methodology. However, we did identify two examples of allelic expression differences in the set of putative enhancer targets that correlated with SNPs in an enhancer region. Both of these SNPs fell within enhancer 19 and showed correlation with allelic expression differences of the TMED6 gene (the two SNPs significantly associated with TMED6 expression had an adjusted P-value False Discovery Rate (FDR)<0.1 for rs7203339 and rs1078621); enhancer 19 falls within the intron of the CDH1 gene, which is 600 kb from the TSS of the TMED6 gene (Fig. 3). A summary of the eQTL analysis of enhancer and promoter risk-associated SNPs can be found in Supplementary Data 4 and Supplementary Fig. 8.

Table 5. Linking transcripts to enhancers using TCGA data.

| Region | Enhancer | Correlated transcripts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enhancer 1 | PITX1(1.37_L1) C5orf20(−1.96_R2) TIFAB(−1.64_R3) CXCL14(−1.39_R5) SLC25A48(−1.34_R7) |

| 1 | Enhancer 2 | PITX1(1.37_L1) C5orf20(−1.96_R2 )TIFAB(−1.64_R3) CXCL14(−1.39_R5) SLC25A48(−1.34_R7) |

| 1 | Enhancer 3 | C5orf20(−1.96_R2) TIFAB(−1.64_R3) CXCL14(−1.39_R5) SLC25A48(−1.34_R7) |

| 1 | Enhancer 4 | PITX1(1.37_L2) C5orf20(−1.96_R1) TIFAB(−1.64_R2) CXCL14(−1.39_R4) SLC25A48(−1.34_R6) TGFBI(2.74_R10) |

| 1 | Enhancer 5 | PITX1(1.37_L2) C5orf20(−1.96_R1) TIFAB(−1.64_R2) CXCL14(−1.39_R4) SLC25A48(−1.34_R6) TGFBI(2.74_R10) |

| 1 | Enhancer 6 | PITX1(1.37_L1) |

| 2 | Enhancer 7 | SQLE(1.8_L6) FAM84B(1.01_L2) POU5F1B(3.02_L1) MYC(1.58_R2) PVT1(2.44_R3) GSDMC(1.75_R4) |

| 2 | Enhancer 8 | None |

| 3 | Enhancer 9 | ARRB1(−1.15_R8) |

| 4 | Enhancer10 | NRIP2(−1.07_L10) FOXM1(1.47_L9) TEAD4(2.15_L6) RAD51AP1(1.36_R5) GALNT8(−1.58_R9) KCNA6(−2.16_R10) |

| 5 | Enhancer 11 | LIMA1(−1.16_L4) METTL7A(−2.65_R3) POU6F1(−1.14_R9) |

| 5 | Enhancer 12 | RACGAP1(1.06_L10) ASIC1(1.49_L9) LIMA1(−1.16_L4) METTL7A(−2.65_R3) POU6F1(−1.14_R9) |

| 5 | Enhancer 13 | LIMA1(−1.16_L4) METTL7A(−2.65_R3) POU6F1(−1.14_R9) |

| 5 | Enhancer 14 | LIMA1(−1.16_L4) METTL7A(−2.65_R3) POU6F1(−1.14_R9) |

| 5 | Enhancer 15 | RACGAP1 (1.06_L10) ASIC1(1.49_L9) LIMA1(−1.16_L4) METTL7A(−2.65_R3) POU6F1(−1.14_R9) |

| 5 | Enhancer 16 | RACGAP1(1.06_L10) ASIC1(1.49_L9) |

| 6 | Enhancer 17 | SMPD3(−1.3_L4) CDH3(6.24_L2) TMED6(−1.36_R10) |

| 6 | Enhancer 18 | SMPD3(−1.3_L4) TMED6(−1.36_R10) |

| 6 | Enhancer 19 | SMPD3(−1.3_L4) CDH3(6.24_L2) TMED6(−1.36_R10) |

| 6 | Enhancer 20 | SMPD3(−1.3_L4) CDH3(6.24_L2) TMED6(−1.36_R10) |

| 7 | Enhancer 21 | KATNAL2(−1.06_L9) ZBTB7C(−2.81_L3) LIPG( 1.3_R6) ACAA2(−1.43_R7) |

| 7 | Enhancer 22 | KATNAL2(−1.06_L9) ZBTB7C(−2.81_L3) LIPG( 1.3_R6) ACAA2(−1.43_R7) |

| 8 | Enhancer 23 | CHST8(−2_R9) KCTD15(−1.02_R10) |

| 8 | Enhancer 24 | CHST8(−2_R9) KCTD15(−1.02_R10) |

| 9 | Enhancer 25 | RBBP8NL(1.33_R3) C20orf166-AS1(−3.81_R6) SLCO4A1(3.19_R7) LOC100127888(2.45_R8) NTSR1(−2.34_R9) MRGBP(1.44_R10) |

| 9 | Enhancer 26 | RBBP8NL(1.33_R2) C20orf166-AS1(−3.81_R5) SLCO4A1(3.19_R6) LOC100127888(2.45_R7) NTSR1(−2.34_R8) MRGBP(1.44_R9) |

| 9 | Enhancer 27 | RBBP8NL(1.33_R3) C20orf166-AS1(−3.81_R6) SLCO4A1(3.19_R7) LOC100127888(2.45_R8) NTSR1(−2.34_R9) MRGBP(1.44_R10) |

| 9 | Enhancer 28 | RBBP8NL(1.33_R2) C20orf166-AS1(−3.81_R5) SLCO4A1(3.19_R6) LOC100127888(2.45_R7) NTSR1(−2.34_R8) MRGBP(1.44_R9) |

TCGA, the cancer genome atlas.

Shown are the subset of the 10 nearest 5′ and 10 nearest 3′ transcripts for each enhancer that show significant gene expression differences in normal versus tumour samples, as determined using RNA-seq data from TCGA. The numbers in parentheses indicate the fold change, with positive indicating a higher expression in tumours. The seven normal-specific enhancers are shown in bold and all genes correlated with these enhancers should be expressed higher in normal cells and thus have a negative value. The R versus L designation indicates the direction and relative location of the transcript with respect to each enhancer (for example, R7 indicates that it is the 7th closest transcript to the enhancer on the ‘right’ side).

Figure 3. Linking a transcript to an enhancers using TCGA data.

(a) Shown is the location of enhancer 19 and the position of the three SNPs (in red) identified in the eQTL studies and two other SNPs (in blue) identified by the FunciSNP analysis but not present on the SNParray, in relation to the H3K27Ac, RNA-seq and TCF7L2 ChIP-seq data for that region. Also shown are the ENCODE ChIP-seq transcription factor tracks from the University of California, Santa Cruz genome browser. (b) The expression of the TMED6 RNA is shown for samples having homozygous or heterozygous alleles for three SNPs in enhancer 19. The upper and lower quartiles of the box plots are the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The whisker top and bottom are 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively. The horizontal line through the box is median value. The P-value corresponds to the regression coefficient based on the residue expression level and the germline genotype. Sample size is listed under each genotype. (c) A schematic of the gene structure in the genomic region around enhancer 19 (yellow box) is shown; the arrows indicate the direction of transcription of each gene. The three genes in the enhancer 19 region that showed differential expression in normal versus tumour colon samples (Table 5) are indicated; of these, only TMED6 was identified in the eQTL analysis.

The effect of enhancer deletion on the transcriptome

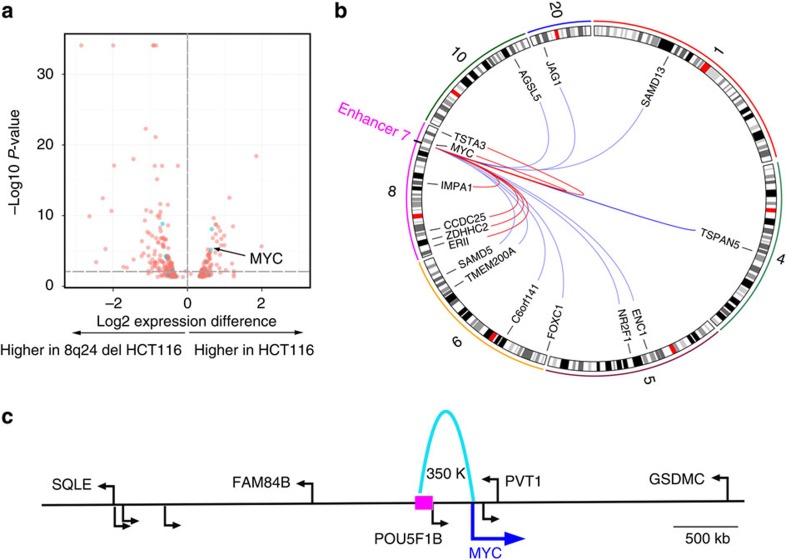

The expression analyses described above provide a list of genes that potentially are regulated by the CRC risk-associated enhancers. However, it is possible that the enhancers regulate only a subset of those genes and/or the target genes are at a greater distance than was analyzed. One approach to identify targets of the CRC risk-associated enhancers would be to delete an enhancer from the genome and determine changes in gene expression. As an initial test of this method, we selected enhancer 7, located at 8q24. The region encompassing this enhancer has previously been implicated in regulating expression of MYC31, which is located 335 kb from enhancer 7. We introduced guide RNAs that flanked enhancer 7, along with Cas9, into HCT116 cells, and identified cells that showed deletion of the enhancer. We then performed expression analysis using gene expression arrays, identifying 105 genes whose expression was downregulated in the cells having a deleted enhancer (Supplementary Data 5); the closest one was MYC, which was expressed 1.5 times higher in control versus deleted cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Identification of genes affected by deletion of enhancer 7.

(a) Shown are the expression differences (x axis) and the significance of the change (y axis) of the genes in the control HCT116 versus HCT116 cells having complete deletion of enhancer 7. The Illumina Custom Differential Expression Algorithm was used to determine P-values to identify the significantly altered genes; three replicates each for the control and deleted cells were used. Genes on chromosome 8 (the location of enhancer 7) are shown in blue. The spot representing the MYC gene is indicated by the arrow. (b) Shown are all genes on chromosome 8 that change in expression and the 10 genes showing the largest changes in expression upon deletion of enhancer 7. The location of the enhancer is indicated and the chromosome number is shown on the outside of the circle. (c) The genes identified as potential targets using TCGA expression data are indicated; of these, MYC is the only showing a change in gene expression upon deletion of the enhancer.

Discussion

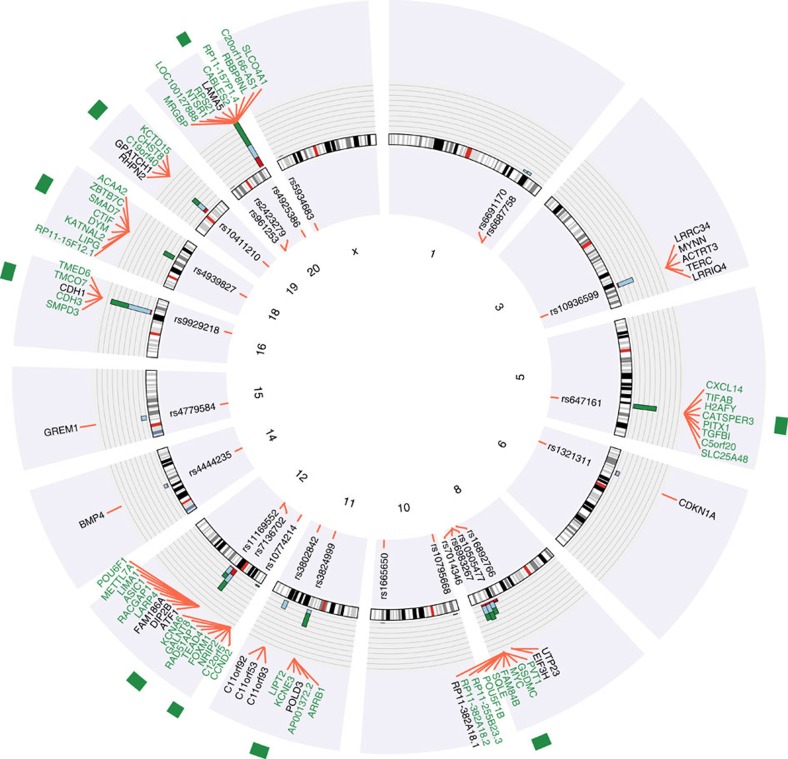

We have used the programme FunciSNP21, in combination with genomic, epigenomic and transcriptomic data, to analyze 25 tag SNPs (and all SNPs in high LD with those tag SNPs) that have been associated with an increased risk for CRC5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Taken together, we have identified a total of 80 genes that may be regulated by risk-associated SNPs. Of these, 24 are directly linked to a gene via a SNP within an exon or proximal promoter region and 56 additional genes are putative target genes of risk-associated enhancers; see Fig. 5 for a schematic summary of the location of the tag and LD SNPs and associated genes, and Supplementary Table 4 for a complete list of genes and how they were identified.

Figure 5. Summary of identified candidate genes correlated with increased risk for CRC.

Shown are the 80 candidate genes identified in this study. For the gene names, green means that it was only identified as a potential enhancer target, the other genes were identified as direct targets either by an exon SNP or a TSS SNP; the putative enhancer target genes were selected as described in the text. For each tag SNP, the relative number of SNPs that identified an exon (red portion), a TSS (blue portion), or an enhancer (green portion) is shown by the bar graph. The nine genomic regions that harbour CRC risk enhancers are shown by the green rectangles outside the circle.

Of the 25 tag SNPs, only one is found within a coding exon, occurring in the third exon of the MYNN gene and resulting in a synonymous change that does not lead to a coding difference. However, by analysis of SNPs in high LD with the 25 tag SNPs, we identified five genes that harbour damaging SNPs and which are expressed in colon cells (HCT116, normal sigmoid colon or TCGA tumours); these are POU5F1B, RHNP2, UTP23, LAMA5 and FAM186A). Interestingly, the retrogene POU5F1B which encodes a homologue of the stem cell regulator OCT4 has recently been associated with prostate cancer susceptibility32. We also identified 23 genes (21 coding and 2 non-coding) that harbour highly correlated SNPs in their promoter regions and are expressed in colon cells. Several of the genes that we have linked to increased risk for CRC by virtue of promoter SNPs show large changes in gene expression in tumour versus normal colon tissue. For example, TERC, the non-coding RNA that is a component of the telomerase complex, was identified by a promoter SNP and has higher expression in a subset of colon tumours (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Similarly, CDH3 (P-cadherin) was identified by a promoter SNP and shows increased expression in many of the colon tumours. Both TERC and CDH3 have previously been linked to cancer33,34. Promoter SNPs also identified three uncharacterized protein-coding genes (c11orf93, c11orf92 and c11orf53) clustered together on chromosome 11. Inspection of H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac ChIP-seq signals suggested that these genes are in open chromatin in normal sigmoid colon, but not in HCT116. Accordingly, the TCGA gene expression data showed that all three genes are downregulated in a subset of human CRC tumours (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Additional genes identified by promoter SNPs that have been linked to cancer include ATF1, BMP4, CDH1, CDKN1A, EIF3H, GREM1, LAMA5 and RHPN2 (refs 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45). For example, BMP4 is upregulated in the HCT116 cells and has been suggested to confer an invasive phenotype during progression of colon cancer41. Interestingly, we also identified GREM1, an antagonist of BMP proteins, and showed that expression of GREM1 is decreased in HCT116. The downregulation of the antagonist GREM1 and the upregulation of the cancer-promoting BMP4 may cooperate to drive colon cancer progression. LAMA5 is a subunit of laminin-10, laminin-11 and laminin-15. Laminins, a family of extracellular matrix glycoproteins, are the major non-collagenous constituent of basement membranes and have been implicated in a wide variety of biological processes including cell adhesion, migration, signalling and metastasis46.

We identified 28 enhancers, clustered in 9 genomic regions, that harbour correlated SNPs. It is important to note that in our studies we have used the appropriate cell types and the appropriate epigenetic mark to identify CRC-associated enhancers. Previous analyses have attempted to link SNPs to enhancers by using transcript abundance, epigenetic marks or transcription factor binding from non-colon cell types47. In contrast, we have used normal and tumour cells from the colon. Of equal importance is the actual epigenetic mark that is used to identify enhancers. A previous study used H3K4me1 to identify genomic regions that were differently marked between normal and tumour colon cells18. However, although H3K4me1 is associated with enhancer regions, this mark does not specifically identify active enhancers. Some regions marked by H3K4me1 are classified as ‘weak’ or ‘poised’ enhancers and it is thought that these regions may become active in different cells or developmental states48. In contrast, H3K27Ac is strongly associated with active enhancers49,50 and we feel that this mark is the most appropriate one for identification of CRC-associated risk enhancers.

Although it is not possible to conclusively know a priori what gene is regulated by each of the identified enhancers, we have derived a list of putative CRC risk-associated enhancer target genes by examining gene expression data from HCT116 cells and from a large number of colon tumours. Several of the genes that are possible enhancer targets are transcription factors that have previously been linked to cancer, including H2AFY, MYC, SMAD7, PITX1, TEAD4 and ZBTB7C. MYC, of course, has been linked to colon cancer by many studies due to the fact that it is a downstream mediator of WNT signalling, which is strongly correlated with colon cancer2. In addition, PITX1, TEAD4 and ZBTB7C are all transcription factors that have been previously linked to the control of cell proliferation, specification of cell fate or regulation of telomerase activity51,52,53,54. Also, PVT1 is a MYC-regulated non-coding RNA that may play a role in neoplasia55,56.

In conclusion, we have used epigenomic and transcriptome information from normal and tumour colon cells to identify a set of genes that may be involved in an increased risk for the development of colon cancer. We realize that we cast a rather large net by analyzing 10 genes 5′ and 10 genes 3′ of each enhancer. We note that five of the genes shown to be differentially expressed in the TCGA data (MYC, PITX1, POU5F1B, C5orf20 and CDH3) are also in the set of nearest three genes to an enhancer having CRC risk-associated SNPs. However, enhancers can also work at large distances. In fact, the eQTL analysis identified TMED6 as a potential target of enhancer 19 (over 600 kb away) and deletion of enhancer 7 identified MYC as a potential target (335 kb away). Future analyses of the entire set of CRC risk-associated enhancers are required to confirm the additional putative long range regulatory loops suggested by our studies. Such studies will provide a high confidence list of genes which, when combined with the genes identified by the TSS risk-associated SNPs, should be prioritized for analysis in tumorigenicity assays.

Methods

RNA-seq

RNA-seq data was downloaded from the Reference Epigenome Mapping Center for analysis of gene expression in sigmoid colon cells (GSM1010974 and GSM1010942). For HCT116 colon cancer cells, RNA was prepared using Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), paired-end libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeqV2 Sample Prep Kit (Catalogue# 15596-026), starting with 1 μg total RNA. Libraries were barcoded, pooled and sequenced using an Ilumina Hiseq. For analysis of RNA-seq data, we used Cufflinks57, a programme of ‘alignment to annotation’ having discontinuous mapping to the reference genome. Messenger RNA (mRNA) abundance was measured by calculating FPKM, to allow inter-sample comparisons. We specified the –G option with the GENCODE V15 comprehensive annotation so that the programme will only do alignments that are structurally compatible with the reference transcript provided. Two biological replicates were performed and the mean FPKM of two biological replicates represents the expression of each gene (GSM1266733 and GSM1266734). We categorized genes into non-expressed, low expressed and expressed based on the distribution of the Gene FPKM (Supplementary Fig. 2) generated by the R package ‘ggplot2’.

RNA-seq data for 233 colorectal tumour samples and 21 colorectal normal samples were downloaded from the TCGA data download website ( https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/dataAccessMatrix.htm); Supplementary Data 6. The data were all generated on the Illumina HiSeq platform, and mapped with the RSEM algorithm and normalized so that the third quartile for each sample equals 1,000. Entrez gene IDs were used for mapping to genomic locations using GenomicRanges ( http://www.bioconductor.org/packages//2.12/bioc/html/GenomicRanges.html). To identify transcripts differentially expressed in the tumour samples, we selected the 10 nearest genes 5′ of and the 10 nearest genes 3′ of each of the 28 enhancers. After removing the non-expressed genes, we then log2 transformed the expression data [log2(RSEM+1)], and performed a t-test on gene expression between the normal group and the tumour group for each gene using 254 TCGA colorectal RNA-seq data sets. We selected statistically significant genes that showed a statisically significant twofold change in expression (P<0.01, after adjustment by Benjamini and Hochberg’s FDR Methods).

To generate the heatmap showing expression of genes in the TCGA samples, we log2-transformed the expression data of the 254 TCGA colorectal samples RNA-seq [log2(RSEM+1)]. Then we computed the mean and s.d. of the expression of the each gene ( and su). We normalized gene expression by

and su). We normalized gene expression by  . Hierarchical clustering with Ward’s method was used to normalize TSS/exon gene expression.

. Hierarchical clustering with Ward’s method was used to normalize TSS/exon gene expression.

ChIP-seq analysis

Two replicate H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data sets from HCT116 cells (ENCODE accession number wgEncodeEH002873) and two replicate H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data sets from normal sigmoid colon ( www.genboree.org/EdaccData/Current-Release/sampleexperiment/-Sigmoid_Colon/Histone_H3K27ac/) were analyzed using the Sole-search ChIP-seq peak calling programme27,28 using the following parameters: Permutation, 5; Fragment, 250; AlphaValue, 0.00010=1.0E−4; FDR, 0.00010=1.0E−4; PeakMergeDistance, 0; HistoneBlurLength, 1,200. Each data set was analyzed separately and also analyzed as a merged data set for HCT116 or sigmoid colon. The merged H3K27Ac peaks from HCT116 or Sigmoid colon were analyzed using the GenomicRanges package of bioconductor to identify promoter versus distal peaks.

Enhancer deletion

Guide RNAs designed to recognize chr8: 128412821-128412843 and chr8: 128414816-128414838 (hg19) were cloned into a genomic RNA cloning vector (Addgene plasmid 41824) and introduced into HCT116 cells by transfection, along with a plasmid encoding Cas9 and green fluorescent protein. Cells were sorted using a flow cytometer to capture the cells having high green fluorescent protein signals and then colonies were grown from single cells. Complete deletion of all alleles for enhancer 7 was confirmed by PCR using primers flanking the enhancer. RNA analysis was performed in triplicate using HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip arrays (Illumina), comparing the deleted cells to parental HCT116 cells.

Analysis of FunciSNP and correlated SNPs effects

To identify SNPs correlated with the 25 CRC tag SNPs and those that overlap with chromatin biofeatures, we use the R package for FunciSNP21, which is available in Bioconductor. We used H3K27ac ChIP-seq data from HCT116 cells and sigmoid colon tissue and as biofeatures we used exon, intron, UTR and TSS annotations generated from GENCODE V15. We ran FunciSNP with the following parameters: ±200 kb around each of the 25 tag SNPs and r2>0.1. To analyze the potential effects of correlated SNPs on protein coding, we employed SnpEff and Provean using suggested default parameters. For analysis of SNPs on transcription factor motifs, we employ a method developed by Hazelett et al.58

Batch effects analysis

We note that TCGA has strict sample criteria. Each frozen primary tumour specimen has a companion normal tissue specimen which could be blood/blood components (including DNA extracted at the tissue source site), or adjacent normal tissue taken from greater than 2 cm from the tumour. Each tumour and adjacent normal tissue specimen (if available) were embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium and a histologic section was obtained for review. Each haematoxylin and eosin stained case was reviewed by a board-certified pathologist to confirm that the tumour specimen was histologically consistent with colon adenocarcinoma and the adjacent normal specimen contained no tumour cells. The tumour sections were required to contain an average of 60% tumour cell nuclei (TCGA has found that this provides a sufficient proportion so that the tumour signal can be distinguished from other cells), with less than 20% necrosis for inclusion in the study per TCGA protocol requirements. To address potential batch effects, we applied MBatch software, which was developed by the MD Anderson Cancer Center and has been widely used to address batch effects in the TCGA Consortium2,59, to perform hierarchical clustering and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to address any potential batch effects in the colorectal TCGA data sets: level 3 mRNA expression (RNA-seq Illumina Hiseq), level 3 DNA methylation (Infinium HM450K microarray), level 4 SNPs copy number variation (CNV) by gene (GW SNP 6). We assessed batch effects for two variables: batch ID and tissue source site. For hierarchical clustering, MBatch uses the average linkage algorithm with 1 minus the Pearson correlation coefficient as the dissimilarity measure. The samples were clustered after labelling with different colours, each of which corresponds to a batch ID or a tissue source site. (Supplementary Figs 6a.1,6b.1 and 6c.1). For PCA, MBatch plotted four principal components (Supplementary Figs 6a.2,3, 6b.2,3 and 6c.2,3). Samples with the same batch ID (or tissue source site) were labelled as same colour and shape and were connected to the batch centroids. The centroids were computed by taking the mean across all samples in the same batch. To assess batch effects on mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. 6a), genes with zero values were removed and normalized gene expression values were log2 transformed before analyzing batch effects. Batch 132 and 154 stood out in one comparison (Comp1 versus Comp2) but not in the other comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 6a.2). The remaining batches or tissue source sites did not stand out in clustering or in any of the PCA plots; thus the data is not supportive of a strong batch effect and all data was used for analysis. When batch effect on CNV (Supplementary Fig. 6b) was analyzed, the centroid for the NH tissue source site stood out among other batches. The remaining batches or tissue source sites did not stand out in clustering or in any of the PCA plots. We did not apply correction on the data because (i) there were only two samples and a centroid calculated by only two samples is likely not accurate, (ii) the two samples within the NH batch were not far from other individual samples and (iii) two samples would not dramatically affect our analysis of 233 samples. When assessing batch affects on DNA methylation analysis, no batches or tissue source sites stood out in clustering or in any of the PCA plots. (Supplementary Fig. 6c). In summary, none of the samples consistently show batch effects in both clustering and PCA algorithms. Based on the above analysis, we believe that batch effects among the data sets are not dramatically influencing our analysis.

eQTL analyses

We employed a two-step linear regression model ,which considers somatic germline genotype, CNV and DNA methylation at gene promoters to perform eQTL analysis60. We selected 228 patients with both tumour samples and matched normal blood or normal tissue samples from the TCGA CRC data set. For each of these patients, we obtained the germline genotypes from normal blood or normal tissue samples using data from the GW SNP6 array platform. We directly downloaded gene-level somatic copy number, gene isoform expression (from the RNAseqHiseq Illumina platform) and DNA methylation data (from the HM450K platform) for each tumour sample from the TCGA data download website ( http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/runs/analyses__2014_01_15/data/COAD/20140115/). To determine DNA methylation of a promoter, we calculated the average DNA methylation at 100 bp upstream of and 700 bp downstream of the TSS for a transcript. We fit the germline genotype of patients, the continuous DNA methylation level of promoters, and the CNV of matched tumour samples into the two-step multivariate linear regression model. Sixty SNPs, including 6 tag SNPs, 18 SNPs within risk enhancers and 45 SNPs within TSS regions, were present on the GW SNP6 array. eQTL analyses were performed using these 60 SNPs and the genes identified by exon or TSS SNPs or by differential expression analysis (see Tables 2 and 5). To reduce false positives, we excluded genes showing log2 expression <2 in over 90% of the samples. The Benjamini–Hochberg method was used to correct the original P-value and FDR of 0.1 was used as the threshold of significant association.

General data handling and visualization

Throughout the analyses we used GenomicRanges to import, export and/or intersect genomic data for plotting and annotation purposes; the R version 3.0.0 (3 April 2013) was used for all statistical analyses, the R function ‘image’ was used for heatmap generation, and package ‘ggplot2’ was used to generate scatterplots. To generate the circle plot, Circos software was used61. All genomic location information is based on hg19.

Author contributions

L.Y. performed all bioinformatic analyses and assisted with manuscript preparation; Y.G.T. performed enhancer characterizations and edited the manuscript; B.P.B. advised L.Y. in bioinformatic analyses; P.J.F. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Yao, L. et al. Functional annotation of colon cancer risk SNPs. Nat. Commun. 5:5114 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6114 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 1-4

Exon, TSS, and enhancer correlated SNPs. Individual worksheets are provided for all correlated SNPs identified in TSS regions, all correlated SNPs found in exons, the subset of nonsynonymous correlated SNPs found in exons, and all correlated SNPs found in the set of 28 enhancers. In all cases, the tag SNP, the LD of the correlated, and genomic information for each SNP is provided.

H3K27Ac ChIP-seq peaks. The sets of H3K27Ac peaks called on merged replicates for HCT116 and sigmoid colon datasets is provided in individual worksheets.

Motif analysis of all correlated SNPs in enhancers. All SNPs having an r2> 0.1 with the 25 CRC tag SNPs were analyzed using motifs from Factorbook (http://www.factorbook.org). For those SNPs that impacted a critical position of a motif, it was determined if the change was predicted to be an improvement or a disruption. A more restrictive list including only the subset of SNP-affected motifs within the robust enhancer regions (using an r2> 0.5 cut-off) are shown in Table 5.

eQTL analysis results. Shown are the results for the SNP-gene pairs using 60 SNPs (6 tag SNPs, 18 SNPs within risk enhancers, and 45 SNPs within TSS regions) present on the GW SNP6 array and the expression of genes identified by exon or TSS SNPs or by differential expression analysis.

RNA analysis of cells having a deletion of enhancer 7. Shown are the genes whose expression decreased in the cells in which enhancer 7 was deleted, as determined using Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip arrays.

TCGA sample IDs. The IDs for HM450K DNA methylation, RNA-seq, SNP arrays, and copy number variation analyses for 228 TCGA samples are provided, as well as the IDs for 254 samples used in normal-tumor gene expression analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UCSD Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Center for use of the H3K27Ac and RNA-seq data from sigmoid colon prior to publication by the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium ( http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/epigenomics/), Sushma Iyengar and Michael Kahn for use of their SW480 ChIP-seq data, Adam Blattler, Fides Lay and Peter Jones for use of their HCT116 RNA-seq data, David Segal and Mital Bhakta for guidance and assistance with the CRISPR technology, the DNA Production Facility at the USC Epigenome Center for library construction and sequencing of RNA samples, and the USC high performance computing and communications center. The HCT116 H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data was produced in the Farnham lab as part of the ENCODE Consortium15. This work was supported in part by 5R21HG006761, U01 ES017154 and P30CA014089 from the National Cancer Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Fearon E. R. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 479–507 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TheCancerGenomeAtlas. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487, 330–337 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindorff L. A. et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9362–9367 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio T. A. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. New Engl. J. Med. 363, 166–176 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanke B. W. et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nat. Genet. 39, 989–994 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson I. P. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies colorectal cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 10p14 and 8q23.3. Nat. Genet. 40, 623–630 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenesa A. et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on 11q23 and replicates risk loci at 8q24 and 18q21. Nat. Genet. 40, 631–637 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters U. et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility loci for colorectal tumors in a genome-wide meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 144, 799–807 e724 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W. H. et al. Genome-wide association analyses in East Asians identify new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 45, 191–196 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlston R. S. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies four new susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 40, 1426–1435 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlston R. S. et al. Meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies identifies susceptibility loci for colorectal cancer at 1q41, 3q26.2, 12q13.13 and 20q13.33. Nat. Genet. 42, 973–977 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop M. G. et al. Common variation near CDKN1A, POLD3 and SHROOM2 influences colorectal cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 44, 770–776 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M. A., Boyle A. P., Kundaje A., Batzoglou S. & Snyder M. Linking disease associations with regulatory information in the human genome. Genome Res. 22, 1748–1759 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentner G. E. & Scacheri P. C. The chromatin fingerprint of gene enhancer elements. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30888–30896 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODEConsortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frietze S. et al. Cell type-specific binding patterns reveal that TCF7L2 can be tethered to the genome by association with GATA3. Genome. Biol. 13, R52 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurano M. T. et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science 337, 1190–1195 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar-Zaidi B. et al. Epigenomic enhancer profiling defines a signature of colon cancer. Science 336, 736–739 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison R. C. Genome-wide epigenetic data facilitate understanding of disease susceptibility association studies. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30932–30940 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnham P. J. Thematic minireview series on results from the ENCODE project: integrative global analyses of regulatory regions in the human genome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30885–30887 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee S. G., Rhie S. K., Berman B. P., Coetzee G. A. & Noushmehr H. FunciSNP: an R/bioconductor tool integrating functional non-coding data sets with genetic association studies to identify candidate regulatory SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6, 80–92 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248–249 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Sims G. E., Murphy S., Miller J. R. & Chan A. P. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE 7, e46688 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koudritsky M. & Domany E. Positional distribution of human transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 6795–6805 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stergachis A. B. et al. Exonic transcription factor binding directs codon choice and affects protein evolution. Science 342, 1367–1372 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blahnik K. R. et al. Sole-search: An integrated analysis program for peak detection and functional annotation using ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e13 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blahnik K. R. et al. Characterization of the contradictory chromatin signatures at the 3′ exons of zinc finger genes. PLoS ONE 6, e17121 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Factorbook.org: a Wiki-based database for transcription factor-binding data generated by the ENCODE consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D171–D176 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A., Lajoie B. R., Jain G. & Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature 489, 109–113 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur I. K. et al. Mice lacking a Myc enhancer that includes human SNP rs6983267 are resistant to intestinal tumors. Science 338, 1360–1363 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer J. P. et al. An expressed retrogene of the master embryonic stem cell gene POU5F1 is associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94, 395–404 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Bryan T. M. & Reddel R. R. Increased copy number of the TERT and TERC telomerase subunit genes in cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 99, 1092–1099 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes J. et al. Epithelial E- and P-cadherins: role and clinical significance in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1826, 297–311 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Smit-McBride Z., Pan X., Rheinhardt J. & Hershey J. W. An oncogenic role for the phosphorylated h-subunit of human translation initiation factor eIF3. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24047–24060 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. The atypical histone macroH2A1.2 interacts with HER-2 protein in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23171–23183 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. MicroRNA-25 functions as a potential tumor suppressor in colon cancer by targeting Smad7. Cancer Lett. 335, 168–174 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis G. S., Berk A., Dimitromanolakis A. & Diamandis E. P. Enrichment map profiling of the cancer invasion front suggests regulation of colorectal cancer progression by the bone morphogenetic protein antagonist, gremlin-1. Mol. Oncol. 7, 826–839 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G. L. et al. Activating transcription factor 1 is a prognostic marker of colorectal cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 13, 1053–1057 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Sun Z., Zhang A. & Zhang J. SMAD7 rs12953717 polymorphism contributes to increased risk of colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 35, 695–699 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H. et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is overexpressed in colonic adenocarcinomas and promotes migration and invasion of HCT116 cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 313, 1033–1044 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danussi C. et al. RHPN2 drives mesenchymal transformation in malignant glioma by triggering RhoA activation. Cancer Res. 73, 5140–5150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro P. et al. Therapeutic targets associated to E-cadherin dysfunction in gastric cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 17, 1187–1201 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garte S. J. The c-myc oncogene in tumor progression. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 4, 435–449 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung E. C. et al. TIGAR is required for efficient intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis. Dev. Cell 25, 463–477 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M. The laminin family. Cell Adh. Migr. 7, 48–55 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Carmona L. G. et al. Fine-mapping of colorectal cancer susceptibility loci at 8q23.3, 16q22.1 and 19q13.11: refinement of association signals and use of in silico analysis to suggest functional variation and unexpected candidate target genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 2879–2888 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. & Kellis M. Discovery and characterization of chromatin states for systematic annotation of the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 817–825 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo E. & Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: what, how, and why? Mol. Cell 49, 825–837 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn S. et al. Tissue-specific analysis of chromatin state identifies temporal signatures of enhancer activity during embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 44, 148–156 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P. et al. Altered subcellular localization of transcription factor TEAD4 regulates first mammalian cell lineage commitment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7362–7367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon B. N. et al. KR-POK interacts with p53 and represses its ability to activate transcription of p21WAF1/CDKN1A. Cancer Res. 72, 1137–1148 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosel T. et al. Loss of desmocollin 1-3 and homeobox genes PITX1 and CDX2 are associated with tumor progression and survival in colorectal carcinoma. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 27, 1391–1399 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D. L. et al. Identification of PITX1 as a TERT suppressor gene located on human chromosome 5. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 1624–1636 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y. et al. Amplification of PVT1 contributes to the pathophysiology of ovarian and breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5745–5755 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppi K., Pitt J. J., Wahlberg B. M. & Caplen N. J. The 8q24 gene desert: an oasis of non-coding transcriptional activity. Front. Genet. 3, 69 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelett D. J. et al. Comprehensive functional annotation of 77 prostate cancer risk loci. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004102 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. Integrative eQTL-based analyses reveal the biology of breast cancer risk loci. Cell 152, 633–641 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 1-4

Exon, TSS, and enhancer correlated SNPs. Individual worksheets are provided for all correlated SNPs identified in TSS regions, all correlated SNPs found in exons, the subset of nonsynonymous correlated SNPs found in exons, and all correlated SNPs found in the set of 28 enhancers. In all cases, the tag SNP, the LD of the correlated, and genomic information for each SNP is provided.

H3K27Ac ChIP-seq peaks. The sets of H3K27Ac peaks called on merged replicates for HCT116 and sigmoid colon datasets is provided in individual worksheets.

Motif analysis of all correlated SNPs in enhancers. All SNPs having an r2> 0.1 with the 25 CRC tag SNPs were analyzed using motifs from Factorbook (http://www.factorbook.org). For those SNPs that impacted a critical position of a motif, it was determined if the change was predicted to be an improvement or a disruption. A more restrictive list including only the subset of SNP-affected motifs within the robust enhancer regions (using an r2> 0.5 cut-off) are shown in Table 5.

eQTL analysis results. Shown are the results for the SNP-gene pairs using 60 SNPs (6 tag SNPs, 18 SNPs within risk enhancers, and 45 SNPs within TSS regions) present on the GW SNP6 array and the expression of genes identified by exon or TSS SNPs or by differential expression analysis.

RNA analysis of cells having a deletion of enhancer 7. Shown are the genes whose expression decreased in the cells in which enhancer 7 was deleted, as determined using Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip arrays.

TCGA sample IDs. The IDs for HM450K DNA methylation, RNA-seq, SNP arrays, and copy number variation analyses for 228 TCGA samples are provided, as well as the IDs for 254 samples used in normal-tumor gene expression analyses.