Abstract

Context

Naltrexone is a medication available in oral form that can completely block the effects produced by opioid agonists, such as heroin. However, poor medication compliance with naltrexone has been a major obstacle to the effective treatment of opioid dependence.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of a sustained-release depot formulation of naltrexone in treating opioid dependence.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week multi-center trial of male and female heroin-dependent patients who participated in the study between September 2000 and November 2003. Participants were stratified by years of heroin use (≥5, <4.9) and gender, and then randomized to receive one of three doses: placebo, 192 mg, or 384 mg depot naltrexone. Doses were administered at the beginning of Week 1 and then again four weeks later at the beginning of Week 5. All participants received twice-weekly relapse prevention therapy, provided observed urine samples, and completed other assessments at each visit.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were retention in treatment and percentage of opioid-negative urine samples.

Results

A total of 60 patients were randomized at two centers. Retention in treatment was dose related with 39%, 60%, and 68% of the patients in the placebo, naltrexone 192 mg, and naltrexone 384 mg groups, respectively, remaining in treatment at the end of the two-month treatment period. Analysis of the time to dropout revealed a significant main effect of dose with mean time to dropout of 27, 36, and 48 days, respectively, for the placebo, naltrexone 192 mg, and naltrexone 384 mg groups. The percentage of urine samples negative for opioids varied significantly as a function of dose, as did the percentage of urine samples negative for methadone, cocaine, benzodiazepines, and amphetamine. The percentage of urine samples negative for cannabinoids was not significantly different across groups. When the data were recalculated without the assumption that missing urine samples were positive, however, a main effect of group was not found for any of the drugs tested with the exception of cocaine, where the percentage of cocaine-negative urines was lower in the placebo group. Adverse events were minimal and generally mild in severity. This sustained-release formulation of naltrexone was well tolerated and produced a robust and dose-related increase in treatment retention.

Conclusion

The present data provide exciting new evidence for the feasibility, efficacy, and tolerability of long-lasting antagonist treatments for opioid dependence.

Introduction

Heroin abuse and, more recently, prescription opioid abuse are significant and growing public health problems in the U.S., as measured by a variety of indicators1–4. Treatment strategies for opioid dependence commonly include agonist maintenance therapies, such as methadone, buprenorphine, and the buprenorphine/naloxone combination. While all of these medications are effective in reducing illicit opioid use5–8, problems associated with their use such as social resistance to the idea of “replacing one drug of abuse with another,” difficulties in tapering patients off the medication due to long-lasting withdrawal effects, and illicit diversion of the maintenance medications make the search for alternative forms of pharmacotherapy important.

Orally delivered naltrexone is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of both opioid and alcohol dependence. It acts as a competitive antagonist at opioid receptors and is highly effective in both preventing and reversing the effects produced by mu opioid agonists. Despite its strong theoretical potential for treating opioid dependence, clinical experience with naltrexone has been disappointing because of high dropout rates during treatment and poor compliance with medication ingestion9–12. The development of sustained-release depot formulations of naltrexone has renewed interest in this medication for treating opioid dependence. Depot naltrexone has also been used recently in the treatment of alcohol dependence13–14. A recent inpatient study conducted in our laboratory demonstrated that an injectable depot formulation of naltrexone was safe, well tolerated, and effective in reducing the subjective, cognitive, and physiological effects of intravenously delivered heroin for 3–5 weeks, depending on dose15. The present study was designed to examine the safety and efficacy of depot naltrexone in a clinical setting for patients who were seeking treatment for opioid dependence.

Methods

Study Participants

Participants were heroin dependent men and women (18–59 years of age), as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), who were voluntarily seeking treatment for their dependence. The target enrollment was 60 patients, stratified by years of heroin use (≥5, <4.9) and gender. Participants were randomized in blocks of 6 into one of three parallel cohorts. Patients were in good health based on medical history, physical examination, vital signs measurements, and 12-lead electrocardiogram, and laboratory tests within appropriate normal ranges (hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis). Patients were excluded from the study if they were dependent on methadone or on drugs other than heroin, nicotine, or caffeine (based on DSM-IV criteria), pregnant or lactating, unwilling to use a satisfactory method of birth control, currently diagnosed with major DSM-IV Axis I psychopathology (e.g., mood disorder with functional impairment, schizophrenia) that might have interfered with study participation, considered to have a significant risk of suicide or had made one or more attempts in the past year, had acute hepatitis or liver damage as evidenced by SGOT or SGPT greater than three times the upper end of the laboratory normal range, had a history of allergy, adverse reaction or sensitivity to the study medication, regularly used psychoactive drugs including anxiolytics and antidepressants, currently received any other investigational drug, or had any medical condition that might have interfered with study participation or significantly increased the medical risks of study participation. Participants were recruited through advertising in local newspapers and through word-of-mouth. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants through a multi-step process in which study procedures were explained by several staff members. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Study Design

The study was designed as a multi-center randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 8-week clinical trial. Patients received an initial inpatient detoxification, followed by oral naltrexone for 3 consecutive days in order to ensure that they were willing and able to tolerate the effects of depot naltrexone. Patients were then randomized to receive placebo, 192 mg, or 384 mg depot naltrexone (Depotrex®, Biotek Inc., Woburn, MA). Four weeks later, patients received a second dose of the study medication. The same dose was administered on both occasions.

Following each dose administration, patients attended the clinic twice per week to receive manualized relapse prevention therapy and to complete various questionnaires designed to assess drug craving, opioid withdrawal symptoms, and global functioning. At each visit, potential adverse events were assessed and patients provided urine samples for analysis of opioids, cocaine, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, methadone, and amphetamine. Urine sample collections were observed by research staff and subsequently analyzed by Northwest Toxicologies, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT). Blood samples for liver function tests and for analysis of naltrexone and 6-beta-naltrexol levels were collected weekly. Depression was assessed twice monthly and patients met with a psychiatrist at least once per month. At the last study visit, hematology and blood chemistry profiles, liver function tests, urinalyses, electrocardiograms, and physical examinations were performed.

Depot Naltrexone

A long-lasting, injectable formulation of naltrexone (Depotrex® was manufactured by BIOTEK, Inc. (Woburn, MA) and provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD). Naltrexone microcapsules and placebo microspheres were packaged in sterile single-dose vials. After reconstituting in suspending medium, 2.4 ml of the suspension was injected. Each single-dose vial of the active formulation contained drug equivalent to 192 mg naltrexone base. This formulation per vial was designed to release approximately 5 mg naltrexone per day. The placebo formulation contained the equivalent weight in polymer microspheres. Injections were administered subcutaneously into the buttocks (one 2.4 ml injection per buttock), using an 18 gauge needle. All participants received two injections to maintain the dosing blind. For the placebo dose, participants received two placebo injections, for the low dose, participants received one placebo and one naltrexone injection (192 mg naltrexone base), and for the high dose, participants received two naltrexone injections (394 mg naltrexone base).

Data Analysis

Analyses of the efficacy measures were conducted on the intent-to-treat population. Primary dependent measures were average number of weeks in treatment and the percentage of negative urine toxicology samples for opioids during the 8-week treatment period. The number of negative samples taken in the 8-week treatment period was used to calculate the percent for each patient. The denominator was the maximum number of possible samples for a completed patient, with the assumption that the missing visits and missing test results were positive16. The data were also recalculated without those assumptions. The difference in the percent of negative urine results between each naltrexone group and the placebo and the difference between the two naltrexone groups was analyzed with a two-way analysis of variance model (ANOVA) including the treatment and center factors. The three pairwise comparisons and the 95% confidence intervals for the differences between treatments were performed using Tukey's method, controlling for the experiment-wise error rate at 0.05. Residuals of the ANOVA were analyzed to verify whether the normality assumption was violated. Levene's test was used to determine whether the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated. If either assumption was violated, then the rank transformation or nonparametric procedure was applied instead. Consistency of the evaluation between the centers was examined with the ANOVA model with the added treatment-by-center interaction term, should there be no signs of violation of the assumptions of ANOVA. Consistency of the evaluation across age, race, and gender for the primary efficacy measure was evaluated with the ANOVA or ANCOVA model.

Secondary dependent measures included the following: time to dropout, percentages of negative urine samples for cocaine, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, amphetamine, and methadone, heroin craving scores, clinical global impression scale scores for severity of opiate and cocaine use rated by clinicians (CGIC) and patients (CGIS), and Hamilton Depression Index (HAM-D) total scores. The distributions of time to dropout in the three treatment groups were compared to determine significance of the difference in retention between treatments. The number of days from randomization to dropout or completion of the study was summarized by treatment. Kaplan-Meier's method was used to estimate the distribution of the time to dropout, where completion of the study was handled as censored observations. The distribution of the time to dropout in each pair of treatment groups was compared using the log-rank test. The percentages of negative urine toxicology outcomes were examined with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. How much or how little the patient felt that he or she wanted and needed heroin since the last visit was rated on a visual analog scale. The craving scores at the post-baseline visits were analyzed with the model for repeated measures to assess significance of the treatment by time interaction and the treatment effect. The severity of opiate and cocaine use was rated on the CGIS and CGIC using an 8-point scale with 1 being no pathology, 7 extreme pathology and 8 not assessed. Patients with no assessment were not included for analysis. The treatment effects on CGIS and CGIC for opiates and cocaine were analyzed with an ANOVA model. If the distribution of CGIS and CGIC concentrated on a few rating scores, then the data were analyzed with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method, stratified by center. The total score of the HAM-D was analyzed with an ANOVA model.

Safety of the treatment was evaluated based on reports of adverse events (AE's), vital signs, liver function tests, clinical lab tests and electrocardiograms. Only the treatment-emergent adverse events were analyzed. Treatment-emergent adverse events were defined as adverse events that occurred after start of study medication or previously occurring adverse events that worsened after start of study medication. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was summarized by treatment, body system and severity. The incidence of the treatment-emergent adverse events that were considered possibly, probably or definitely related to the study medication was summarized similarly. Adverse events that resulted in discontinuation were tabulated by treatment group and listed individually. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events in each naltrexone group was compared with that of the placebo group using the Fisher's exact test.

Clinical monitoring was performed under the direction of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The primary clinical monitoring was performed by Biopharmaceutical Research Consultants, Inc. (BRCI, Dexter, MI). BRCI conducted periodic audits during and after the study on all case report forms and corresponding source documents for each participant. The BRCI monitors assured that submitted data were accurate and in agreement with source documentation, verified that investigational agents were properly stored and accounted for, verified that patients' consent for study participation had been properly obtained and documented, confirmed that research participants entered into the study met inclusion and exclusion criteria, and assured that all essential documentation required by good clinical practices guidelines were appropriately filed.

Results

Demographics A total of 60 patients were randomized at 2 centers. Patients were between 19 and 59 years old, 77% of whom were male. The White and Black races were equivalent at 37% and 35%, respectively, and were the majority. The distributions of gender, age, and race were not significantly different in the three groups (Table 1). Lifetime drug use was quite similar across all groups, as was drug use in the past 30 days (Table 1). There were no significant differences between study sites for any of the demographic measures or for any of the dependent measures described below.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic Characteristics

| Variables | Placebo | Naltrexone 192 mg | Naltrexone 384 mg | All | P-Values1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| (N=18) | (N=20) | (N=22) | (N=60) | |||

| SEX | Male | 12 (67%) | 15 (75%) | 19 (86%) | 46 (77%) | 0.380 |

| Female | 6 (33%) | 5 (25%) | 3 (14%) | 14 (24%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| RACE | White | 7 (39%) | 7 (35%) | 8 (37%) | 21 (37%) | 0.342 |

| Black | 7 (39%) | 5 (25%) | 9 (41%) | 21 (35%) | ||

| Hispanic | 3 (17%) | 5 (25%) | 3 (14%) | 11 (18%) | ||

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Other | 1 (6%) | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (7%) | ||

|

| ||||||

| AGE (years) | 18 – 30 | 3 (17%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (18%) | 11 (18%) | 0.849 |

| 30 – 59 | 15 (83%) | 15 (80%) | 18 (82%) | 49 (82%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40 (11) | 42 (10) | 41 (11) | 41 (10) | ||

| Range | 20 – 59 | 26 – 59 | 19 – 56 | 19 – 59 | ||

|

| ||||||

| HEROIN USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 15.1 (11.8) | 15.7 (12.0) | 10.7 (9.8) | 13.7 (11.1) | 0.385 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 29.3 (2.6) | 28.7 (4.6) | 24.4 (2.4) | 29.2 (3.2) | 0.903 |

|

| ||||||

| METHADONE USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 1.5 (3.3) | 1.1 (1.2) | 3.0 (6.2) | 1.9 (4.3) | 0.256 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.137 |

|

| ||||||

| OTHER OPIOID USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.8 (2.6) | 1.9 (7.8) | 1.0 (5.0) | 0.557 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.4 (1.2) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.631 |

|

| ||||||

| BARBITURATE USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.155 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | - |

|

| ||||||

| OTHER SEDATIVE USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.944 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.8) | 1.4 (3.8) | 0.5 (1.3) | 0.7 (2.3) | 0.297 |

|

| ||||||

| COCAINE USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 4.4 (5.5) | 4.8 (8.6) | 3.6 (6.6) | 4.2 (6.9) | 0.803 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 3.1 (5.7) | 2.1 (4.5) | 1.3 (2.4) | 2.1 (4.3) | 0.537 |

|

| ||||||

| ALCOHOL USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 2.0 (4.1) | 0.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (6.0) | 1.6 (4.4) | 0.769 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.997 |

|

| ||||||

| CANNABIS USE | ||||||

| Lifetime (Years) | Mean (SD) | 5.5 (8.9) | 9.2 (13.2) | 9.8 (11.3) | 8.3 (11.2) | 0.505 |

| Past Month (Days) | Mean (SD) | 3.5 (8.1) | 4.1 (8.8) | 2.4 (5.8) | 3.3 (7.5) | 0.777 |

P-values for comparisons of the distributions of gender and race among treatment groups are based on the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (general association) stratified by center. P-values for comparisons of the distributions of age, height, weight and drug use among treatment groups are based on a two-way ANOVA model containing the effect of treatment and center.

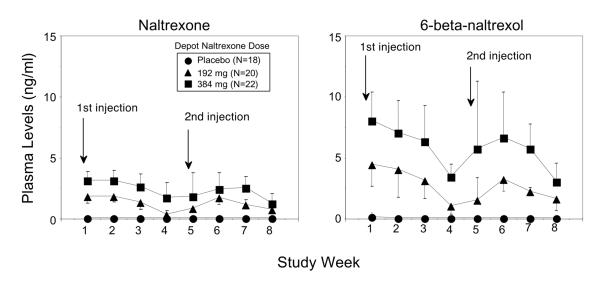

Plasma levels of study medication Plasma levels of naltrexone (Figure 1, left panel) and 6-beta-naltrexol (Figure 1, right panel) are shown as a function of study week and treatment group. After administration of 192 mg depot naltrexone, average naltrexone plasma levels ranged between 0.4 and 1.9 ng/ml. After administration of 384 mg depot naltrexone, average naltrexone plasma levels ranged between 1.3 and 3.2 ng/ml. Across the 8-week study, plasma naltrexone levels tended to be fairly constant, with perhaps a slight decline during the fourth week after drug administration. Plasma levels of 6-beta-naltrexol, the primary pharmacologically active metabolite of naltrexone, tended to be higher than naltrexone and more variable across time and between subjects.

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of naltrexone and 6-beta-naltrexol.

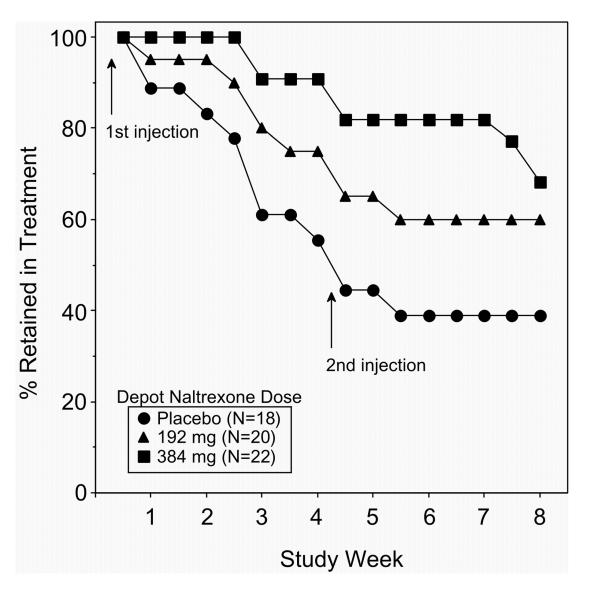

Retention in treatment and time to dropout The percentage of patients retained in treatment (Figure 2) is presented as a function of study week and treatment group. During the first visit, all randomized subjects were present. By Week 8-Visit 16, 7 patients out of 18 randomized in the placebo group (39%), 12 patients out of 20 randomized in the 192 mg naltrexone group (60%), and 12 patients out of 22 randomized in the 384 mg naltrexone group (68%) remained in treatment. The distribution of time from randomization to dropout or completion in the three treatment groups was compared to determine the significance of the difference in retention between groups (Table 2). The number of days to dropout was lowest in the placebo group (27 days; 3.8 weeks), followed by the naltrexone 192 mg group (36 days; 5.1 weeks), and the naltrexone 384 mg group (48 days; 6.8 weeks). The main effect of group was significant at P<0.002. Pairwise comparisons between groups revealed a significant difference in days to dropout between the placebo and 384 mg naltrexone groups (P<0.0001) and between the two active dose groups (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Retention in treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of Time to Dropout by Treatment

| Placebo | Naltrexone 192 mg | Naltrexone 384 mg | P-Value | Pairwise Comparisons1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18) | (N=20) | (N=22) | Treatment2 | P-Value | ||

| Number of Days from Randomization to Dropout / Completion | ||||||

| Mean | 27 | 36 | 48 | |||

| SD | 19 | 20 | 13 | |||

| Range | 2 – 65 | 1 – 60 | 16 – 59 | 0.002 | 192 – 0 | 0.129 |

| 384 – 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| 384 – 192 | 0.046 | |||||

P-values for pairwise comparisons among treatment groups were based on the Kaplan-Meier's methods, where completion of the study was handled as censored observation. P-values for paired comparisons were using the log-rank test.

0: Placebo group; 192: 192 mg naltrexone group; 384: 384 mg naltrexone group.

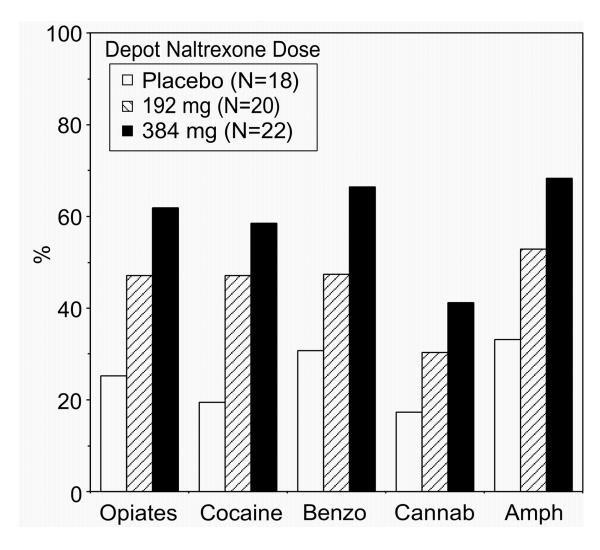

Urine drug toxicology The mean percentage of urine samples negative for opioids across the study was lowest for the placebo group (25.3%) and highest for the 384 mg naltrexone group (61.9%; Table 3, Figure 3). The main effect of group was significant (P<0.03). Pairwise comparisons between groups revealed a significant difference between the placebo and 192 mg naltrexone groups (P<0.04) and the placebo and 384 mg naltrexone groups (P<0.001). However, when the data were recalculated without the assumption that missing visits and missing samples were positive, the mean percentage of urines negative for opioids increased to 74.2% in the placebo group, 73.5% in the 192 mg naltrexone group, and 79.4% in the 384 mg naltrexone group and there were no significant differences between groups.

Table 3.

Analysis of Percent (%) of Negative Opioid Urine Samples by Treatment

| Placebo | Naltrexone 192 mg | Naltrexone 384 mg | Pooled SD | P-Value | Pairwise Comparisons1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=18) | (N=20) | (N=22) | Treatment2 | P-Value | 95% CI | |||

| Percentage (%) of negative opioid urine samples when missing urines were considered positive 3 | ||||||||

| Mean | 25.3 | 47.1 | 61.9 | |||||

| SD | 17.2 | 38.2 | 28.7 | |||||

| Range | 0 – 64.7 | 0 – 100 | 0 – 100 | 30.4 | 0.026 | 192 – 0 | 0.037 | (−1.9, 45.5) |

| 384 – 0 | <0.001 | (13.2, 60.1) | ||||||

| 384 – 192 | 0.166 | (−7.6, 37.3) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Recalculation: Percentage (%) of negative opioid urine samples when missing urines were NOT considered positive 4 | ||||||||

| Mean | 74.2 | 73.5 | 79.4 | |||||

| SD | 33.4 | 33.2 | 28.9 | |||||

| Range | 0 – 100 | 0 – 100 | 0 – 100 | 32.5 | 0.847 | 192 – 0 | 0.952 | (−25.9, 24.6) |

| 384 – 0 | 0.609 | (−19.8, 30.2) | ||||||

| 384 – 192 | 0.548 | (−18.0, 29.8) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Percentage (%) of missing urine samples | ||||||||

| Mean | 64.4 | 42.7 | 29.4 | |||||

| SD | 21.7 | 32.4 | 21.5 | |||||

| Range | 11.8 – 88.2 | 0 – 88.2 | 0 – 82.4 | 25.6 | 0.024 | 192 – 0 | 0.026 | (−42.3, −1.0) |

| 384 – 0 | <0.001 | (−55.2, −14.7) | ||||||

| 384 – 192 | 0.131 | (−32.9, 6.3) | ||||||

P-values for pairwise comparisons among treatment groups were based on a two-way ANOVA model containing the effect of treatment, center and the center-by-treatment interaction. The pairwise comparisons and the 95% CIs were performed using Tukey's method.

0: Placebo group; 192: 192 mg naltrexone group; 384: 384 mg naltrexone group.

The % was calculated for each subject with the denominator being 17 (2 samples per week for 8 weeks plus an additional sample collected when the second dose of depot naltrexone was administered). This denominator was used when the data were calculated with the assumption that missing urine samples were positive.

The data were calculated originally with the assumption that missing urine samples would be considered as positive. The recalculated data are presented without that assumption.

Figure 3.

Percentage of negative urines when missing urines were considered positive.

Similar trends in the average percentage of negative urines as a function of group (Figure 3) were obtained for cocaine (P<0.003), benzodiazepines (P<0.02), amphetamine (P<0.03), and methadone (P<0.05) when the missing values were calculated as positive for the drug of interest. The difference among the three groups for cannabinoids was not significant (P<0.08). The percentage of missing urines (Table 3) was inversely related to the percentage of negative urines with the highest percentage of missing urines for the placebo group (64.4%), followed by the 192 mg naltrexone group (42.7%) and the 384 mg naltrexone group (29.4%).

Across time, the percentage of urines negative for cocaine was significantly lower in the placebo group than in the naltrexone 192 mg at Week 1-Visit 2 (30% vs 90.9%; P<0.003), Week 2-Visit 4 (62.5% vs 93.8%; P<0.03), Week 5-Visit 10 (33.3% vs 100%; P<0.03) and Week 7-Visit 14 (0% vs 100%; P<0.01). The percentage of urines negative for cocaine was significantly lower in the placebo group than in the naltrexone 384 mg group at Week 1-Visit 2 (30% vs 88.9%; P<0.002), Week 3-Visit 6 (71.4% vs 100%; P<0.04) and Week 7-Visit 14 (0% vs 84.6%; P<0.04). The percentages of urines negative for benzodiazepines and methadone were significantly lower in the placebo group than in the naltrexone 384 mg group at Week 7-Visit 13 (66.7% vs 100%; P<0.02 for both drugs). There were no significant differences in the percentages of negative urines among groups for cannabinoids or amphetamine.

When the data were recalculated without the assumption that missing values were positive, there were no significant differences between groups for any of the drugs. For cocaine, the average percentage of negative urine samples was lower, but not significantly so, in the placebo group (65.7%), compared to the naltrexone 192 mg (86.0%) and naltrexone 384 mg groups (83.9%). The average percentage of urines negative for cannabinoids ranged between 60.7% and 63.5% across the three groups, and the average percentage of negative urines ranged between 87.8% and 100% for benzodiazepines, amphetamine, and methadone.

Heroin craving At baseline, heroin craving was high for all three groups: mean ratings of “wanting heroin” and “needing heroin” ranged between 54 mm and 64 mm on a 100 mm line. After receiving the study medication, the lowest heroin craving scores were reported by the naltrexone 192 mg group for the majority of visits (range: 1–28 mm). No statistically significant differences (p=0.217) were found for ratings of “wanting heroin” among the treatment groups during the study. However, patients who received active depot naltrexone reported “needing heroin” less than those who received placebo (p=0.002). The pairwise comparisons for ratings of “needing heroin” showed that there were significant differences between placebo and naltrexone 192 mg (p<.001), and between placebo and naltrexone 384 mg (p<.001), but insignificant differences between naltrexone 192 mg and naltrexone 384 mg (p=0.195).

Clinical Global Impression Scale There was no obvious pattern of difference or statistical significance between the mean CGI scores across visits among the three treatment groups.

Hamilton Depression Total Score (HAM-D) Throughout the study, depression scores did not significantly differ across the three treatment groups. At baseline, mean HAM-D total scores for the placebo, 192 mg, and 384 mg groups were 14.8 (N=17), 14.6 (N=19) and 13.3 (N=20), respectively. By Week 8-Visit 16, mean HAM-D scores for the placebo, 192 mg, and 384 mg groups were 4.0 (N=2), 6.7 (N=9) and 3.1 (N=14), respectively.

Adverse Events Overall In the placebo group (N=18), 9 patients (50%) experienced an adverse event (AE), 4 patients (22%) experienced a treatment-related AE, and 1 patient (6%) discontinued study participation because of an AE. In the naltrexone 192 mg group (N=20), 13 patients (65%) experienced an AE, 8 patients (40%) experienced a treatment-related AE, and 2 patients (11%) discontinued because of an AE. In the naltrexone 384 mg group (N=22), 15 patients (68%) experienced an AE, 3 patients (14%) experienced a treatment-related AE, and 0 patients discontinued because of an AE. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in the number of AE's, treatment-related AE's, or discontinuations due to AE's.

Treatment-related Adverse Events The most common treatment-related AE's were found among “general disorders and administration site conditions” (e.g., fatigue, injection site induration, injection site pain), where 2 AE's (11.1%) were reported in the placebo group, 6 (30%) were reported in the naltrexone 192 mg group, and 3 (13.4%) were reported in the naltrexone 384 mg group. Five patients who were discontinued from the study included one patient from the placebo group who experienced an injection site induration, one patient from the naltrexone 192 mg group who experienced an injection site redness, mass and induration, one patient in the naltrexone 192 mg group who experienced a headache, and two patients from the naltrexone 192 mg group who experienced increases in liver function tests (see below). All of the injection site reactions were rated as moderate in severity and resolved spontaneously within 2–3 weeks.

Treatment-emergent Adverse Events Two serious adverse events occurred during the study. One 50-year old patient developed diabetes mellitus after receiving the second dose of 384 mg naltrexone. The relationship to the study medication was noted as being “unlikely.” Three months after the end of study participation, a patient who received 192 mg naltrexone made a suicide attempt, which was deemed unrelated to the study.

Liver function tests AST, ALT, and GGT values were within twice the upper limit of the normal range throughout the study, with the exception of one participant who was discontinued prior to administration of the second set of injections due to elevated GGT values (AST and ALT values were only mildly elevated). This patient was being treated for hepatitis C by his primary care physician and it was felt that the most conservative medical approach would be to discontinue him from the study. A second patient demonstrated 4–7 fold increases in ALT, AST, and GGT values over pre-naltrexone values, accompanied by other symptoms including jaundice, dark-colored urine and light-colored stools, within one week following administration of 192 mg depot naltrexone. This patient, who was hepatitis negative during screening, subsequently tested positive for hepatitis C and it was determined that the acute increases in LFT values most likely occurred as a result of this new infection.

Discussion

Although sustained-release preparations of naltrexone have been investigated since the 1970s17–23, problems with bio-compatibility have prevented their widespread use. The present study represents the first prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a sustained-release formulation of naltrexone for the treatment of opioid dependence. The data demonstrate that this 30-day, injectable form of naltrexone was safe and effective in retaining heroin-dependent patients in treatment. The fact that the percentage of urine samples negative for opioids was high (75–80%) regardless of depot naltrexone dose suggests that patients who attend clinic visits are more likely to abstain from using opioids and other drugs of abuse, with the possible exception of cocaine and cannabinoids. By increasing treatment retention, depot naltrexone will allow patients greater contact with appropriate supportive counseling to reduce drug use and ease the transition to a life without heroin.

Across the time points measured, the average peak naltrexone plasma levels measured approximately one week after administration of 192 mg and 384 mg of depot naltrexone were 1.9 (± 0.6) and 3.2 (± 0.7) ng/ml, respectively, which were consistent with the levels that we reported in our previous study of the same formulation of depot naltrexone15. For comparison, a single oral dose of 50 mg naltrexone produces average peak naltrexone plasma concentrations of approximately 9 ng/ml (Cmax) at 1 hr after drug administration (Tmax)24. The mean half-life of naltrexone was 3.6 hr, with large individual variability in values, which is common with drugs subject to extensive first-pass metabolism24. In general, many investigators agree that doses that maintain naltrexone plasma levels of approximately 2 ng/ml are sufficient for antagonizing of the effects of high doses of opioid agonists.

One potential concern with a long-lasting antagonist is that patients will attempt to override the blockade by using large amounts of heroin, thereby placing themselves at increased risk of overdose, especially during the period when naltrexone blood levels are decreasing. This concern is particularly relevant given the literature in laboratory animals demonstrating an up-regulation in µ opioid receptors following discontinuation of chronic treatment with opioid antagonists25–33. In normal human participants, however, a study of morphine sensitivity before and after naltrexone treatment failed to show any evidence of μ receptor up-regulation in the respiratory control system, the most likely site of opioid overdose lethality34. There have also been reports of increased opioid overdose in patients following discontinuation of oral naltrexone maintenance, compared to discontinuation of agonist replacement therapies35–36. The more appropriate comparison, however, would be between discontinuation of naltrexone and discontinuation of long-term abstinence because in both cases, the former heroin user has remained free of opioids and thus there is significant loss of tolerance and greater risk of overdose. In the present study, several participants used heroin after receiving the depot injections, but there was no evidence that attempts to override the blockade were successful and no accidental or intentional opioid overdoses. In fact, a previous study demonstrated that the incidence of opioid overdoses dramatically decreased in “high-risk” adolescents treated with an implantable form of naltrexone37. Another study by the same group, using a larger sample size, also showed that the incidence of opioid overdoses decreased following administration of a naltrexone implant, even beyond the period of expected effectiveness of the implant38. It is possible that the gradual dissipation of naltrexone from these sustained-release formulations protected these patients from experiencing opioid overdose.

Another potential concern with a sustained-release formulation of naltrexone is that the use of non-opioid drugs may increase. This phenomenon apparently did not occur in the present study because other drug use remained relatively low throughout the study. These data are consistent with other studies demonstrating that other drug use declines when patients stop using heroin39–40. However, one report concluded that sedative and perhaps other drug “overdoses” may increase following administration of a naltrexone implant38. Several of the sedative overdoses occurred soon after implant administration, suggesting that the presence of residual opioid withdrawal symptoms may have prompted the use of benzodiazepines. Because patients who met criteria for current dependence on other drugs of abuse were excluded from the present study, it is difficult to conclude confidently that other drug use does not increase after treatment with sustained-release naltrexone. Future studies with a more heterogeneous drug-abusing population should carefully assess potential changes in the amounts and patterns of other drug use.

Potential adverse events that may be unique to sustained-release formulations of naltrexone include the possibility that patients will attempt to remove the medication, as well as tissue reactions around the site of drug administration. In the present study, none of the participants attempted to remove the medication. This particular risk is lower for injectable depot formulations of naltrexone because patients are informed beforehand that it is impossible to remove the medication once it is administered. With implantable formulations of naltrexone, some reports, though rare, do exist of patients attempting to remove the medication. With regard to tissue reactions around the site of injections, the formulation of depot naltrexone used in the present study was well tolerated. Of the three patients dropped from the study because of injection site reactions, the severity was considered to be moderate and all reactions resolved spontaneously over time.

Impairment in liver function is a common concern with naltrexone therapy because early studies suggested that high doses of naltrexone may produce hepatotoxicity39. However, several subsequent studies, including those conducted in alcoholics and in patients with severe liver disease, generally have not shown clinically significant changes in liver function after treatment with naltrexone42–45. With the exception of the one patient who was diagnosed with new-onset hepatitis C following depot naltrexone administration, clinically significant elevations in liver enzymes did not occur in the present study, nor did they occur in our previous study with the same formulation of depot naltrexone15. The hepatitis resolved uneventfully in the patient who received 192 mg depot naltrexone just prior to being diagnosed with hepatitis C. A similar case was reported in a patient who received a naltrexone implant46. These results are particularly reassuring given the high prevalence of hepatitis C among injecting heroin users47.

In sum, the present results demonstrate that this injectable, sustained-release formulation of naltrexone was safe, well tolerated and effective in retaining patients in treatment. An increase in treatment retention is particularly important because it will allow clinicians sufficient time to engage patients in psychotherapy so that they can learn to make other psychological and social adjustments supporting a life without opioids. Medication non-compliance has been cited as a major problem with oral naltrexone therapy, making firm conclusions regarding the efficacy of naltrexone in the treatment of opioid dependence difficult48. One reason for high treatment dropout is that discontinuation of naltrexone ingestion has no negative physical consequences, as opposed to discontinuation of agonist maintenance therapies which results in the emergence of opioid withdrawal symptoms. For most opioid abusers, the decision of whether to take a medication that produces no psychoactive effects or to “get high” is a difficult one. The availability of sustained-release formulations of naltrexone holds the promise of allowing patients to circumvent their ambivalence over taking the medication, and to focus instead on other issues relevant to sustaining abstinence.

Acknowledgments

The assistance with data collection by Pamela Parris, Meredith Kelly, Sarah Dubner, and Andre Roche is gratefully acknowledged. The authors also express their gratitude to Randi Adelman, RN and Gary Pagliaro, RN for their medical assistance and to Drs. Edward Nunes and Kenneth Carpenter for reviewing an early draft of the manuscript. Additional thanks are due to Drs. Elie Nuwayser and James Kerrigan of Biotek, Inc. for providing Depotrex®. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the 2004 annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence in San Juan, Puerto Rico. This research was supported by Center Grant P50 DA09236 and by Center Grant P60 DA05186 and the VA/NIDA Interagency Agreement at Philadelphia VA Medical Center. Biopharmaceutical Research Consultants, Inc. received funding for data management and statistical support under contract N01DA-1-8817, and the University of Utah and Northwest Toxicology received funding for bioanalytical support under contract N01DA-3-8829.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Office of Applied Studies, Emergency department trends from the drug abuse warning network, Preliminary Estimates January-June 2001 with Revised estimates 1994 to 2000. Rockville, MD: 2002a. (DAWN Series D-20). DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 02-3634. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (SAMSHA) Summary of National Findings Office of Applied Studies. Volume I. Rockville, MD: 2002c. Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. (NHSDA Series H-17). DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3758. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Technical Appendices and Selected Data Tables. Office of Applied Studies. Volume II. Rockville, MD: 2002d. Office of Applied Studies, Results From the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. (NHSDA Series H-18). DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3759. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: Position statement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bickel WK, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Jasinski DR, Johnson RE. Buprenorphine: Dose-related blockade of opioid challenge effects in opioid dependent humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;247:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ. A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA. 1992;267(20):2750–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling W, Wesson DR, Charuvastra C, Klett CJ. A controlled trial comparing buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in opioid dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:401–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1025–1030. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azatian A, Papiasvilli A, Joseph A. A study of the use of clonidine and naltrexone in the treatment of opioid addiction in the former USSR. J Addict Dis. 1994;13(1):35–52. doi: 10.1300/J069v13n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callahan EJ, Rawson RA, McCleave B, Arias R, Glazer M, Liberman RP. The treatment of heroin addiction: Naltrexone alone and with behavior therapy. Int J Addict. 1980;15(6):795–807. doi: 10.3109/10826088009040057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosten TR, Kleber HD. Strategies to improve compliance with narcotic antagonists. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1984;10(2):249–266. doi: 10.3109/00952998409002784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capone T, Brahen L, Condren R, Kordal N, Melchionda R, Peterson M. Retention and outcome in a narcotic antagonist treatment program. J Clin Psychology. 1986;42(5):825–833. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198609)42:5<825::aid-jclp2270420526>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kranzler HR, Wesson DR, Billot L. Naltrexone depot for treatment of alcohol dependence: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(7):1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000130804.08397.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O'Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comer SD, Collins ED, Kleber HD, Nuwayser ES, Kerrigan JH, Fischman MW. Depot naltrexone: Long-lasting antagonism of the effects of heroin in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s002130100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lachin JM. Worst-rank score analysis with informatively missing observations in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1999;20(5):408–422. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahams RA, Ronel SH. Biocompatible implants for the sustained zero-order release of narcotic antagonists. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1975;9:355–366. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820090310. 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alim TN, Tai B, Chiang CN, Green T, Rosse RB, Lindquist T, Deutsch SI. Tolerability study of a depot form of naltrexone substance abusers. In: Harris LS, editor. Problems of Drug Dependence 1994. Vol. 2. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 1995. p. 253. NIDA Research Monograph No. 153 (NIH Publ. No. 95-3883) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang CN, Hollister LE, Gillespie HK, Foltz RL. Clinical evaluation of a naltrexone sustained-release preparation. Drug Alc. Depend. 1985a;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(85)90076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiang CN, Kishimoto A, Barnett G, Hollister LE. Implantable narcotic antagonists: A possible new treatment for narcotic addiction. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1985b;21:672–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrigan SE, Downs DA. Pharmacological evaluation of narcotic antagonist delivery systems in rhesus monkeys. In: Willete RE, Barnett G, editors. Narcotic Antagonists: Naltrexone Pharmacochemistry and Sustained-Release Preparations. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1981. pp. 77–92. NIDA Research Monograph 28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heishman SJ, Francis-Wood A, Keenan RM, Chiang CN, Terrill JB, Tai B, Henningfield JE. Safety and pharmacokinetics of a new formulation of naltrexone. In: Harris LS, editor. Problems of Drug Dependence 1993. Vol. 2. 1994. NIDA Research Monograph No. 141 (NIH Publ. No. 94-3749) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin W, Sandquist VL. A sustained release depot for narcotic antagonists. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1974;30:31–33. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760070019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer MC, Straughn AB, Lo M-W, Schary WL, Whitney CC. Bioequivalence, dose-proportionality, and pharmacokinetics of naltrexone after oral administration. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1984;45(9):15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardo MT, Bhatnagar RK, Gebhart GF. Chronic naltrexone increases opiate binding in brain and produces supersensitivity to morphine in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Brain Res. 1983;289:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bardo MT, Neisewander JL. Chronic naltrexone supersensitizes the reinforcing and locomotor-activating effects of morphine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1987;28:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paronis CA, Holtzman SG. Increased analgesic potency of mu agonists after continuous naloxone infusion in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:582–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paronis CA, Holtzman SG. Sensitization and tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of mu-opioid agonists. Psychopharmacol. 1994;114:601–610. doi: 10.1007/BF02244991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tempel A, Gardner EL, Zukin RS. Neurochemical and functional correlates of naltrexone-induced opioid receptor up-regulation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;232:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tempel A, Zukin S, Gardner EL. Supersensitivity of brain opiate receptor subtypes after chronic naltrexone treatment. Life Sci. 1982;31:1401–1404. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoburn BC, Inturrisi CE. Modification of the response to opioid and nonopioid drugs by chronic opioid antagonist treatment. Life Sci. 1988;42:1689–1696. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young AM, Mattox SR, Doty MD. Increased sensitivity to rate-altering and discriminative stimulus effects of morphine following continuous exposure to naltrexone. Psychopharmacol. 1991;103:67–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02244076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unterwald EM, Rubenfeld JM, Imai Y, Wang J-B, Uhl GR, Kreek MJ. Chronic opioid antagonist administration upregulates mu opioid receptor binding without altering mu opioid receptor mRNA levels. Mol. Brain Res. 1995;33:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00143-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornish JW, Henson D, Levine S, Volpicelli J, Inturrisi C, Yoburn B, O'Brien CP. Naltrexone maintenance: effect on morphine sensitivity in normal volunteers. Am. J. Addictions. 1993;2:34–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritter AJ. Naltrexone in the treatment of heroin dependence: relationship with depression and risk of overdose. Australian and New Zealand J. Psychiatry. 2002;36:224–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diguisto E, Shakeshaft A, Ritter A, O'Brien S, Mattick RP, the NEPOD Research Group Serious adverse events in the Australian National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD) Addiction. 2004;99(4):450–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hulse GK, Tait RJ. A pilot study to assess the impact of naltrexone implant on accidental opiate overdose in “high risk” adolescent heroin users. Addict. Biol. 2003;8(3):337–342. doi: 10.1080/13556210310001602257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulse GK, Tait RJ, Comer SD, Sullivan MA, X, Arnold-Reed D. Reducing hospital presentations for opioid overdose in patients treated with sustained release naltrexone implant. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.009. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunteman GH, Condelli WS, Fairbank JA. Predicting cocaine use among methadone patients: analysis of findings from a national study. Hosp. Comm. Psychiatry. 1992;43:608–611. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fairbank JA, Dunteman GH, Condelli WS. Do methadone patients substitute other drugs for heroin? Predicting substance use at 1-year follow-up. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1993;19(4):465–474. doi: 10.3109/00952999309001635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malcolm R, O'Neil PM, Sexauer JD, Riddle FE, Currey HS, Counts C. A controlled trial of naltrexone in obese humans. Int. J. Obesity. 1985;9(5):347–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brahen LS, Capone TJ, Capone DM. Naltrexone: Lack of effect on hepatic enzymes. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1988;28:63–70. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Croop RS, Faulkner EB, Labriola DF. The safety profile of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240090013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marrazzi MA, Wroblewski JM, Kinzie J, Luby ED. High-dose naltrexone and liver function safety. Am. J. Addict. 1997;6:21–29. doi: 10.3109/10550499708993159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sax DS, Kornetsky C, Kim A. Lack of hepatoxicity with naltrexone treatment. J. Clin. Pharmcol. 1994;34:898–901. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1994.tb04002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brewer C, Wong JS. Naltrexone: Report of lack of hepatotoxicity in acute viral hepatitis, with a review of the literature. Addict. Biol. 2004;9(1):81–87. doi: 10.1080/13556210410001674130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freeman AJ, Zekry A, Whybin LR, Harvey CE, van Beek IA, de Kantzow SL, Rawlinson WD, Boughton CR, Robertson PW, Marinos G, Lloyd AR. Hepatitis C prevalence among Australian injecting drug users in the 1970s and profiles of virus genotypes in the 1970s and 1990s. Med. J. Aust. 2000;172:588–591. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirchmayer U, Davoli M, Verster AD, Amato L, Ferri M, Perucci CA. A systematic review on the efficacy of naltrexone maintenance treatment in opioid dependence. Addiction. 2002;97(10):1241–1249. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]