Abstract

Little is known about internet and social media use among homeless youth. Consistent with typologies prevalent among housed youth, we found that homeless youth were using internet and social media for entertainment, sociability, and instrumental purposes. Using Haythornwaite’s (2001) premise that it is important to look at the types of ties accessed in understanding the impact of new media, we found that homeless youth were predominantly using e-mail to reach out to their parents, caseworkers, and potential employers, while, using social media to communicate with their peers. Using the “Social Capital” perspective, we found that youth who were connecting to maintained or bridging social ties were more likely to look for jobs and housing online than youth who did not.

Keywords: homeless youth, internet, online social activities, online social capital, online resource seeking, multiple uses of internet and social media

Introduction

The use of the Internet and social media among adolescents has become nearly ubiquitous in the United States (Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr, 2010; Maczewski, 2002; Pascoe, 2009; Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter, & Espinoza, 2008). Adolescent Internet use has led to a host of new research questions around issues of interpersonal connectivity and teen relationships. There is a growing body of theoretical and empirical work addressing issues of how adolescents in the general population are impacted by Internet use. However with a few exceptions (Karabanow & Naylor, 2007; Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2001; Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2007; Wells & Mitchell, 2008), there is a relative dearth of such work on high-risk adolescents, such as runaway and homeless youth. While there has been a great amount of work on homeless youth’s experiences on the streets, especially the ways in which they enter, sustain, or exit street life (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999; Milburn et al., 2007; Milburn et al., 2009), relatively little is known about their internet use and its consequences.

The relative lack of resources facing homeless youth might suggest that homeless youth would have low levels of Internet use; however, new research has revealed that Internet use is pervasive among these youth. Recent studies have found that more than 80% of homeless youth get online more than once per week, and approximately one-quarter use the Internet for more than 1 hour every day (Rice, Monro, Barman-Adhikari, & Young, 2010). This nascent body of research has primarily focused on how sexual and drug-taking risk behaviors of homeless youth are associated with their online behavior (Barman-Adhikari & Rice, 2011; Rice et al., 2010; Young & Rice, 2011). With the exception of one Canadian study (Karabanow & Taylor, 2007); there has been no broad-based examination of the general uses of the internet and social media among this group of youth, especially in the United States. However, this study was conducted with only 20 youth, and focused on the qualitative experiences of internet access and literacy among homeless youth. The purpose of the present article is to expand on this prior research and examine the wide-ranging ways in which homeless youth use the internet and social media, the social context of their use, and how it might facilitate connections to positive relationships and online resource seeking.

Internet and Social Media as a Resource for Homeless Youth

Homeless youth are one of the most marginalized groups in the United States, and struggle with various issues. A large proportion of these youth have a history of sexual or physical abuse, foster care or juvenile justice involvement, and/or come from dysfunctional families, characterized by parental violence or substance abuse (Booth & Zhang, 1996; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Additionally, they are exposed to other deleterious circumstances once they become homeless, starting from the lack of basic needs such as food, housing, and monetary resources, to more serious physical and emotional health-related needs (e.g. Milburn et al., 2006; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). The longer youth spend on the streets the more likely they are to experience a wide range of negative behavioral outcomes, including: contracting sexually transmitted diseases, experiencing incarceration, attempting suicide, using drugs and alcohol, and participating in exchange sex (trading sex for money, food, drugs, or shelter) (Milburn et al., 2006).

Homeless youth have fewer personal and social resources compared to their housed peers, which contribute to their marginalization. Given their life context, Internet and social media may act as resource for these otherwise resource-poor youth in many ways. First, the interactive and informative nature of the Internet creates an environment amenable to “learning, confidence, and self-empowerment” (Sanyal, 2000, p. 146). Studies show that the internet acts as a powerful resource for information among American youth (Louge, 2006; Suzuki & Calho, 2004); this could especially true for homeless youth who might otherwise lack such resources. A recent study found that homeless youth were actively utilizing the Internet to look for health and sexual health information (Barman-Adhikari & Rice, 2011). Eyrich-Garg (2010), likewise, has found that homeless adults are using their time online to look for jobs and housing. Therefore, it is possible that homeless youth are also using the Internet to look for information or services that connect them with much need resources such as jobs or housing.

Second, the internet and social media enables the creation and maintenance of social networks (Servon & Pinkett, 2004), especially for homeless youth. Adolescence is a critical period for the development of social relationships (Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2005), and these social relationships to a certain extent determine the developmental trajectory of youth. Prior to the Internet becoming more easily accessible, homeless youth had very few avenues through which they could connect with their family and friends from home. This was especially problematic because among homeless youth, it has been found that positive social networks (such as ties from home) are associated with fewer risky behaviors (Johnson et al., 2005; Rice, Stein, & Milburn, 2008) and delinquent networks (often comprising of other street youth) facilitate risky behaviors (Rice et al., 2008; Wenzel, Tucker, Golinelli, Green, & Zhou, 2010). Among housed adolescents, it has been widely suggested that internet use may be distancing youth from parental involvement in favor of greater peer involvement (Lenhart, Rainie, & Lewis, 2001; Subramanyam & Greenfield, 2008). While it is logically possible that Internet use is further distancing homeless youth from their families, it could also be hypothesized that the internet and social media might offer an inexpensive and convenient means through which these youth might be able to keep in touch with family and friends outside of their street relationships. This assumption finds some resonance in the empirical literature as well. Karabanow and Naylor (2007) reported in their qualitative study with 20 homeless youth in Canada that a number of these youth indicated that the internet offered them a way of maintaining their connections with family and friends. Therefore, it is likely that the internet and social media has opened up new avenues for information seeking, and communication and consequently maintaining social relationships for these otherwise isolated youth.

Online Activities of Homeless Youth

Adolescents in the general populace usually use the internet to communicate, establish and maintain relationships, find information on a variety of issues, and for recreational and entertainment purposes (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2009). Few studies have attempted to investigate whether these typologies are also applicable to the homeless youth population. In one of the few studies looking broadly at Internet use among homeless persons, Eyrich-Garg (2010) found that homeless adults were using their time online to have fun, socialize, and pursue resources such as housing, medical care, and employment. Given youth’s greater comfort with technology relative to adults (Lenhart et al., 2001; Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2001; Subrahmanyam et al., 2004), it seems reasonable that homeless youth would likewise engage in multifaceted uses of the internet, perhaps more pervasively and regularly than homeless adults. As an empirical investigation of the online activities for homeless youth, we posit several potential uses of time online for homeless youth, specifically: entertainment, sociability, and instrumental purposes. They may spend their time on entertainment playing video games, listening to music, or watching streaming video. While these youth are homeless, they are still adolescents and are active participants in youth culture (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). They may also use the internet for sociability. Youth may also be using their time online for instrumental purposes related to their homelessness. Thus, we are led to our first research question:

RQ1: What are the different ways in which homeless youth are using their time online?

Online Sociability for Homeless Youth and Uses of Multiple Media

Beyond a technical innovation, the internet is more importantly a new social environment that enables communication through various platforms such as e-mail, instant messaging, social media, blogs, and chat rooms (Greenfield & Yan, 2006). In her treatment of social ties and new media, Haythornthwaite (2002) points out that the use and impact of new media depends upon the type of tie connecting the communicators. The particular media chosen for communicating with others is influenced by people’s relationships, including their geographic proximity and the type of relationship (Copher, Kanfer, & Walker, 2002; Matei & Ball-Rokeach, 2002; Quan-Haase Wellman, Witte, & Hampton, 2002). This perspective has gained more prominence in the internet and social media literature because of initial findings that the internet was associated with a greater likelihood of social isolation and reduced psychological well-being (Kraut et al., 1998; Nie & Erbring, 2000). More specifically, Kraut et al. (1998) found that internet use facilitated the development of poorer quality, weaker-tie, Internet-based relationships, which replaced stronger, more intimate face-to-face relationships. Baym, Zhan, & Lin (2004) argue that such a dichotomy is superficial and that in reality, there is quite a bit of overlap between one’s online and offline (or face-to-face) contacts. Moreover, even when online relationships are activated, they do not necessarily replace their face-to-face ties (Baym et al., 2004). Following the same logic, Haythornwaite (2001) argues that it is not the attribute of the media itself, which determines the type of interaction, but it is rather the attribute of the relationships that determines which media is used to access what kind of ties. Therefore, in understanding internet and social media use, it is important to focus on the social activities for which the medium is used (DeSanctis & Poole, 1994; Orlikowski, Yates, Okamura, & Fujimoto, 1995).

Homeless youth may prefer communicating with particular types of ties with different types of media. Baym et al. (2004) found that as people’s online interactions become more significant, they preferred to conduct these interactions over e-mail rather than through social media, which is much more public. Among homeless youth, e-mail may be the preferred route of communication for reaching out to parents, potential employers, and caseworkers, because it allows for more dyadic, personal, and detailed interactions. This is especially important for messages that need to be tracked and stored. For example, applicants might refer to a past e-mail when referring to a job that they had applied for (Miyata, 2006). Similarly, communications with parents tend to be more intimate than communications with peers, and this might motivate homeless youth to use e-mail more frequently with their parents. For just the opposite set of reasons, due to the ease of sociability on social media websites, this medium may be the preferred route for connecting with peers, regardless of the physical location of those peers. This has been evidenced in empirical studies of housed youth. Thus, we are led to our second question:

RQ2: Do homeless youth use the internet and social media differently to connect with different types of relationships?

Specific hypotheses include:

H1: Homeless youth will use e-mail to connect to adults and institutions such as family members, caseworkers, and potential employers.

H2: Homeless youth will use social networking sites to connect to similarly aged peers (both street and home-based peers).

Social Capital and Online Resource Seeking

As previously mentioned, the Internet can serve as a “resource for stability” for homeless youth. There are multitudes of purposes toward which internet time can be spent by homeless youth, including for instrumental uses, such as searching for housing or employment. Instrumental uses are critical for a group of youth who are resource deprived. Work on homeless youth has repeatedly demonstrated that housing and employment are critical resources, which can lead youth toward long-term stability and away from homelessness (Milburn et al., 2007; Milburn et al., 2009; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). Online activities not only allow homeless youth to search for these jobs, but it also allows them to access critical members of their social networks who can assist them in locating these resources. The face-to-face networks of homeless youth are highly marginalized from mainstream/housed society and generally comprise of other homeless youth (Rice, Milburn, & Rotheram-Borus, 2007; Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999). These networks are examples of networks that lack the social capital needed to locate jobs and housing. However, Internet provides a means by which these youth are able to communicate with their nonstreet connections (such as family, friends from home, and caseworkers), and these connections in turn might support these youth’s motivation to look for resources that enable their exit out of homelessness (Karabanow & Naylor, 2007).

Social Capital Theory provides a succinct framework for thinking about how online social interactions may facilitate resource seeking for homeless youth. The core idea driving Social Capital Theory is that social capital is a property of relationships and represents an investment in relationships that have expected returns (e.g., Lin, 1999; Putnam 2000). Some relationships lead to the information, influence, and reinforcement needed to secure returns such as jobs, business opportunities, or political appointments (Lin, 1999). Social Capital Theory stresses the idea that some communities (or networks) have more or less social capital than others (e.g., Bourdieu, 1983; Burt, 1992; Coleman, 1988; Lin, 1982; Lin, 1999; Portes, 1998; Putnam, 1993). Three types of social capital are useful when thinking about how the internet and social media may influence homeless youth: 1) maintained social capital (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007), 2) bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000), and 3) bonding social capital (Putnam, 2000). Ellison and colleagues (2007) introduced the concept of “maintained social capital,” which can be particularly relevant to homeless youth. They describe maintained social capital as the process of using online network tools that allow individuals to keep in touch with a social network after physically disconnecting from it. In the case of homeless youth, the Internet helps them maintain their relationships with family members or friends from back home, who would otherwise be inaccessible. Bridging social capital is social capital shared amongst heterogeneous groups of people, and increases through brokerage as individuals establish or maintain links to people who are different from themselves (Putnam, 2000). Homeless youth could use the Internet to reach out to ties which bridge outside of street life (such as caseworkers and employers), which also appears to be common (Karabanow & Naylor, 2007; Rice et al., 2010). Bonding social capital is social capital shared amongst a homogenous group of people, and increases through network closure. In the case of homeless youth, this would mean that they are connecting with other homeless youth who are also resource-poor (Stablein, 2011). It is possible that homeless youth could use the internet and social media primarily to communicate with other homeless youth and solidify those ties.

In the case of homeless youth, bonding social capital likely does little for helping youth secure “resources for stability,” whereas bridging social capital and maintained social capital are likely extremely useful. Because street networks are comprised primarily of jobless and homeless individuals, the processes of network closure does little to help members of these communities secure jobs and housing. Bridging social capital and maintained social capital, however, describe the processes of establishing or maintaining ties to individuals outside of street life, such as family, home-based peers, potential employers, and social workers. These ties embed youth in relationships, which could yield information, positive influence, social credentials, and reinforcement needed to secure jobs or housing. While conversations with social workers or potential employers could be face-to-face, many youth are highly transient and may effectively communicate with these persons via e-mail or social media, as well. Moreover, many youth are physically dislocated from their home-based peers and family and rely primarily on the internet to maintain these connections (Rice, 2010; Rice et al., 2010). This leads to our final research question:

RQ3: How do social relationships maintained over e-mail and social networking websites affect online resource seeking?

Specific hypotheses include:

H3: Homeless youth who have connections to parents and home-based peers online (i.e., maintained social capital) will be more likely to look for jobs and housing on the internet than homeless youth who do not have these online connections.

H4: Homeless youth who have online connections to caseworkers and potential employers (i.e., bridging social capital) will be more likely to look for jobs and housing online than homeless youth who do not have these online connections.

Methods

Participants

A convenience sample of 201 homeless youth was recruited between June 1 and June 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California at one drop-in agency serving homeless youth. Any client, aged 13 to 24, receiving services at the agency was eligible to participate. Youth voluntarily signed up to participate in the survey at the same time they signed up to receive services at the agency (e.g., showering, clothing, and case management). A consistent set of two research staff members were responsible for all recruitment and assessment to prevent youth from completing the survey multiple times. Youth who reported never using the internet (n = 7) were dropped from subsequent analyses, yielding a final sample of 194. Since the survey was anonymous and did not retain any identifying information, all participants were provided with an information sheet that explained the study procedures and their rights as human subjects in research. For youth 13 to 17 years old, a waiver of parental permission was obtained. All youth accessing services at the agency were homeless or precariously housed and by definition, those under 18 years are unaccompanied minors.

Since, there is a general lack of consensus on what constitutes homelessness, for the purposes of this study; we defined “homeless youth” as youth who are without a consistent residence. This can include the “literally homeless” (i.e., youth living on the streets, in abandoned buildings, or living in emergency shelters) youth who are “temporarily housed” (i.e., living in transitional living programs or with friends and relatives for less than 6 months), youth who are “stably housed” (i.e., living in transitional living programs or with friends and relatives for more than 6 months, but who still access services at the homeless drop-in center).

Materials and Procedures

All surveys were conducted in a private space at the agency. The survey was a computer-administered self-interview, in which youth answered survey items pertaining to Internet and social networking technology use, demographics, sex and drug risk taking behaviors, living situation, service utilization, and mental health. The survey lasted approximately 60 minutes. All participants received a $20 gift card as compensation for their time. Survey items and procedures were approved by the University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

All demographic variables presented in Table 1 were based on self-report, including race/ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation (self-identification), and current living situation. Years homeless was calculated by subtracting adolescent’s current age from their self-reported age of first homelessness experience. Gender is a dummy variable coded 1 for youth who self-identified as male, and 0 for females and transgender youth. Sexuality is also a dichotomous variable with youth who reported identifying as gay/lesbian, bisexual, or unsure of their sexual orientation being coded as 1 and 0 for those who reported being heterosexual. Current living situation was aggregated into three categories: youth who are literally homeless (i.e., they live on the streets or in emergency shelters), youth who are in temporary housing (i.e., for less than 6 months), and youth who are more stably housed (i.e., they have been housed for more than 6 months). To preserve degrees of freedom for the purposes of the multivariate model, we dichotomized housing situation to literal homelessness being coded as 1 and temporary or stable housing as 0.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Internet-Using Homeless Youth (n = 194) Los Angeles, CA 2009.

| Race | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| African American | 66 | 34.02 |

| Latino | 23 | 11.86 |

| White | 48 | 24.74 |

| Mixed Race | 34 | 17.53 |

| Other/Non-Identified | 23 | 11.86 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 128 | 65.98 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Unsure (GLB) | 62 | 31.96 |

| Current Living Situation | ||

| Literal homelessness (streets or emergency shelters) | 83 | 43.92 |

| Temporary housing (less than 6months) | 77 | 40.74 |

| Stable housing (6months or more) | 29 | 15.34 |

| mean | std dev | |

| Age | 21.06 | 2.05 |

| Years Homeless | 3.82 | 3.91 |

Internet use variables are presented in Table 2. Internet use was measured with the question, “Not counting right now, when was the last time you were on the Internet?” The responses were “(1) More than a week ago, (2) A few days ago, (3) Day before yesterday, (4) Yesterday, and (5) Today.” Internet access was assessed with the question, “The last time you used the internet, where did you go to get online?” Responses were “(1) A youth service agency (2) Public library (3) Your own computer (4) A computer at a friend or associate’s house/apartment (5) An internet café (6) At school (7) At work (8) My cell phone or other device and (9) Other.” What youth chose to do online was assessed with, “The last time you got online, what did you do?” Responses were “(1) Checked your e-mail (2) checked your MySpace or Facebook account (or other social network websites) (3) Looked at videos on YouTube or other video sites (4) Checked for jobs and (5) Looked for housing.”

Table 2.

Recent Online Behaviors of Internet-Using Homeless Youth (n = 194) Los Angeles, CA 2009.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Not counting right now, when was the last time you were on the Internet? | ||

| (5) More than a week ago | 31 | 16.32 |

| (2) A few days ago | 23 | 12.11 |

| (3) Day before yesterday | 19 | 10.00 |

| (4) Yesterday | 59 | 31.05 |

| (5) Today | 58 | 30.53 |

| The last time you used the Internet, where did you go to get online? | ||

| (1) A youth service agency | 40 | 21.16 |

| (2) A public library | 47 | 24.87 |

| (3) Your own computer | 35 | 18.52 |

| (4) A computer at a friend or associates house/apartment | 21 | 11.11 |

| (5) An internet café | 14 | 7.41 |

| (6) At school | 10 | 5.29 |

| (7) At work | 6 | 3.17 |

| (8) My cell phone or other mobile device | 11 | 5.82 |

| (9) Other | 5 | 2.65 |

| The last time you got online, what did you do (check all that apply) | ||

| (1) Checked your e-mail | 124 | 63.91 |

| (2) Checked your MySpace or Facebook account (or other social network website) | 111 | 57.22 |

| (3) Looked at videos on YouTube or other video sites | 53 | 27.32 |

| (4) Checked for jobs | 54 | 27.84 |

| (5) Looked for housing | 25 | 12.89 |

note: exact wording of questions and answers appears

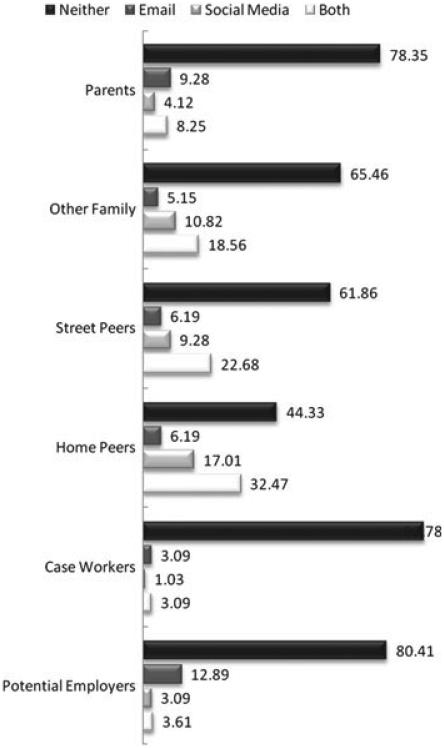

Variables assessing with whom youth connect (also used to operationalize bridging, bonding, and maintained social capital) were based on the responses to two items, “When you use social networking websites like MySpace or Facebook, who do you communicate with (check all that apply)?” and “Who do you use your email to communicate with (check all that apply)?” Answers included: “(1) Parents (including foster family or step family); (2) Brothers, sisters, cousins or other family members; (3) Friends or associates you know from the streets of Hollywood; (4) Friends or associates you know from home (before you came to Hollywood); (5) Caseworkers, social workers, or staff at youth agencies and (6) Potential employers.” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Social Tie by Media

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS™ (SAS Institute Inc., 2000-2004). Descriptive analyses were conducted to obtain frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for interval level variables. Two separate logistic regression models were run to understand how internet use and social ties variables were associated with online resource seeking, more specifically looking for jobs, and housing online.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents a broad overview of the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, current living situation, and age. Out of the 194 youth, 34% were female and 66% were male. In terms of race/ethnicity, the respondents were fairly heterogeneous with 34% of youth identifying as African American, 24% Caucasian, 12% Latino, 17 % mixed ethnicity, and 12% other. Average age for the sample was 21 years.

Online Activities of Participants

Our first research question entailed a description of the various online activities that homeless youth engage in. Table 2 presents the results for recent online behaviors of internet-using homeless youth, specifically when and where they last accessed the internet and the different online activities they were engaging in. More than three-quarters (72%) of the youth, reported they used the internet within the last two days prior to responding to this survey. Almost one-third (31%) of the youth reported they used the internet on the day this survey was conducted; about 30% indicated they had used the internet a day prior to the survey, and 10% reported they used the internet two days prior to the survey. Concerning the venues where these youth gained access to the internet, nearly half (47%) of the youth reported using a public library to get online, nearly one-third (40%) reported gaining access at a youth service agency, and one fifth (11%) reported gaining access at the place where they were staying at night. The youth in this study reported using the internet for various purposes. More specifically, nearly two-thirds (64%) of the participants reported using the internet to send and receive e-mail, and more than half (57%) of the participants reported using the internet to access social networking websites (such as Facebook and MySpace). Regarding the instrumental purposes of the internet, about one-third (28%) of the sample reported using the internet to try to locate housing and about one-eighth (13%) of the participants reported looking for housing.

Types of relationships accessed through e-mail and social media

In order to investigate our second research question, which sought to understand the social context of online communication, we ran descriptive statistics to assess what specific types of relationships were accessed via the different types of media medium (see Figure 1). The results indicate that patterns for e-mail use and social networking website use differ slightly. Overall, youth tend to use e-mail more frequently to connect to parents, caseworkers, and potential employers, but online social networking websites were used to connect to peers (including nonparental family). More specifically, 9% and 13% of youth reported they were using e-mail to connect to family or employers respectively, compared to 32% and 23% of youth who reported they were using social media outlets (such as Facebook and MySpace) to connect to home-based and street-based peers respectively.

Social capital and online resource seeking

In order to understand how online social interactions can facilitate social capital for homeless youth, we ran two multivariate logistic regressions to assess the associations between the internet use and social ties variables with that of online resource seeking. The results indicate that Internet and social media do provide these youth with a viable means through which they can leverage their limited social capital by bridging out to nonstreet relationships. Being literally homeless and having connections to home-based peers and employers online were all significantly associated with looking for a job online (p < .05). In particular, youth who were literally homeless were less likely to look for a job online than youth who were stably housed (OR = .33, p < .05). Youth who were connecting to home-based peers online were also more likely to look for jobs online than youth who were not (OR = 2.57, p < .05). Youth who were connecting to potential employers online were also more likely to look for a job online (OR = 2.59, p < .01). In the second model, time since first homeless and having connections to caseworkers online was significantly associated with looking for housing online (p < .05). More specifically, youth who had spent more time homeless were more likely to look for jobs online (OR = 1.06, p < .05). Youth who were connecting to caseworkers online were 6.7 times more likely to report looking for housing online than youth who were not (OR = 6.7, p < .01).

Discussion

There has been very little investigation on the use and influence of Internet and social media among homeless youth. This study provides us with important insights into the role of internet and social media in the lives of homeless youth. First, like housed youth (Charney & Greenberg, 2001; Ferguson & Perse, 2000; Pappacharissi & Rubin 2000), homeless youth use the internet and social media for a variety of purposes. While these youth may have less regular access to the internet than housed persons do, homeless youth also use the internet to obtain information, fulfill recreation and entertainment needs, and to socialize. When homeless youth reported their online activities at last access, the most common responses were checking e-mail (64%) and checking social networking websites (56%). Clearly socializing is a critical part of time online for homeless youth, just as it is for housed youth (Lenhart et al., 2001; Subrahmanyam et al., 2008). Like their housed counterparts, homeless youth spend some of their time online having fun (Charney & Greenberg, 2001; Ferguson & Perse, 2000). Among our sample of Internet-using youth, 27% reported having looked at videos on YouTube, the last time they got online. Using the Internet for more goal-oriented activities such as looking for jobs or housing was also an important set of activities.

Second, these data lend support to Haythornthwaite’s (2002) general proposition that the type of tie impacts the media with which people connect and reinforces the results of other studies that have documented differential use of communication media depending upon relationship type (Copher et al., 2002; Matei & Ball-Rokeach, 2002; Quan-Hasse et al., 2002). The present data suggest that homeless youth prefer e-mail, the more established media, when communicating with nonpeers. This seems to mirror trends in the general population of youth. As youth have been the first to adopt newer technologies such as social networking websites (Lenhart et al., 2001; Subrahmanyam et al., 2004), homeless youth may be using e-mail when connecting to non-peers because they rightly perceive many of these nonpeers to be nonusers of the media. In general, e-mail seems to be the preferred means of communication when privacy is an issue (Baym et al., 2004). There may be added issues of privacy that encourage e-mail use among homeless youth when connecting with parents, caseworkers, and potential employers. Homeless youth often try to hide their homelessness (Whitbeck & Hoyt, 1999) and a youth may not want to discuss their needs for housing publicly on social networking websites, whereas such a conversation over e-mail is much more confidential and comfortable. It is also possible that parents and other adults might not be active users of social media platforms and might therefore prefer to communicate through e-mail.

Third, bridging social capital (Putnam, 2000) and maintained social capital (Ellison et al., 2007) seem to be important for homeless youth when they are using the internet to attempt to acquire “resources for stability.” Housing and employment are critical resources, which might facilitate youth successfully exiting homelessness and regaining stability (e.g., Milburn et al., 2006). Connecting with home-based peers online is a type of maintained social capital (Ellison et al., 2007). Homeless youth are successfully using the internet to maintain their relationships with peers who are not physically proximate and who may have access to different networks. Having such a connection is associated with reporting having looked for jobs online.

Likewise, connecting to potential employers and caseworkers are examples of accessing bridging social capital. These persons are not a part of street networks. Connecting with potential employers is important to searching for jobs, just as connecting to caseworkers is important when looking for housing. The social capital of street-based networks is not particularly helpful to successfully acquiring jobs and housing, as networks of other homeless youth tend not to have connections to such resources (Rice et al., 2007). Youth must bridge outside of these street-based networks to search for such resources. E-mail and social networking websites provide new opportunities for homeless youth in having easier means to engage in these processes of bridging to other networks.

Finally, another notable finding that emerged out of this study is the association between housing status and online resource seeking, more specifically, looking for jobs. Homeless youth’s experience with internet is entrenched within the complexity of the challenges that they face in their day-to-day lives (Karabanow & Naylor, 2007). Therefore, in exploring homeless youth’s access to the internet, it would be prudent to consider the wider social context within which internet access might be facilitated or hindered. Previous studies have found that homeless youth who had personal internet access, relative to youth who relied solely on public internet access, reported higher rates of HIV/STI and HIV testing information seeking (Barman-Adhikari & Rice, 2011). Therefore, it is possible that youth who are in stable or temporary housing have better access to the internet than those who are without any form of housing. Additionally, it is possible that youth who literally homeless are still struggling to meet their immediate needs (such as food, clothing, and housing), and finding employment is not a priority.

Limitations

There are three important limitations to the current study. First, these data are self-reports and youth may be over- or underrepresenting their actual use of the internet. However, the use of computer-assisted self-interviews, as we employed, have been documented to mitigate issues of social desirability and impression management (Schroeder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003), and lead to more honest and unbiased responses. Despite mitigating social desirability, accurately capturing time online may be impacted by recall error. A kind of diary method or other observational method would yield more accurate results. However, because of the fluidity of their living situation, it becomes very difficult to track down homeless youth and therefore, it becomes very difficult to observe or follow them over an extended period of time, which makes it extremely unlikely to implement these two modes of data collection with this population. Second, these data are drawn from a convenience sample, and are subject to the biases of such a sampling strategy. In particular, it is possible that prosocial adolescents, who have more connections outside of street life, were apt to volunteer for the survey and thus these data may be slightly biased toward prosocial adolescents and their relatively more home-based communication patterns. Data collected from homeless adolescents, however, is frequently drawn from convenience samples (Greene et al., 1999; Tyler et al., 2003). The lack of residential stability or institutional attachments inherent to homelessness make residential or school-based sampling strategies impossible and often convenience sampling at agencies serving adolescents is the most viable way to collect data from this population. Third, we did not collect data on the media literacy or media competence of these youth. It is entirely possible that youth who are more digital media savvy are capable of both making internet searches for housing or jobs and using the internet to effectively communicate with their social networks. This media competence may be an individual-level predictor of both observed behaviors. Fourth, this data was collected as a part of a larger study and did not collect detailed data linking specific relationships to specific types of communication via specific media. Such data would do much to enhance our understanding of how homeless youth are using the internet and social media. Moreover, our understanding of how social capital impacts homeless youth’s use of media would be improved. For example, the present study tells us that homeless youth who are looking for housing online are also connecting to caseworkers; but how that communication with a caseworker is related to that housing search is unspecified. Our understanding of how homeless youth use technology, and the relationships they create and maintain with these technologies would be greatly enhanced by collecting detailed, tie-specific social network data that focuses on what kinds of resources flow across those ties (e.g., information about housing, information about jobs) and what media (e.g., e-mail, social networking websites, cell phones) are used to create and maintain such ties.

Implications

Although this study is exploratory, these findings have important implications for policy and interventions involving homeless youth and other vulnerable youth populations. This study demonstrates that internet and social media can serve as powerful resources for homeless youth in meeting their social and instrumental needs. Therefore, it becomes important that internet accessibility is made more convenient for these youth. This becomes especially essential for youth who are literally homeless, and have to rely on public places (such as libraries and youth service agencies) to gain internet access. Policy-makers should contemplate specialized funding streams for youth-serving agencies to set up computer labs in order to mitigate this existing “digital divide.” While it is encouraging that homeless youth are pursuing employment and housing related activities online, one also needs to acknowledge that these youth’s computer and internet literacy might be limited. Computer classes could be offered where these skills can be learned and honed. Since, most employment applications are now submitted online, caseworkers could work with these youth to locate these opportunities and assist them in creating their resumes and foster other online job etiquette skills such as inquiring about employment opportunities over e-mail. The ubiquity of internet use among homeless youth also opens up the possibility of delivering interventions online (Eyrich-Garg, 2011). In previous studies, prevention and intervention programs that are delivered online have proven to be both viable and effective (Moskowitz, Melton, & Owczarzak, 2009; Ybarra & Bull, 2007). Therefore, if these programs are designed and tailored for the homeless youth population, it could prove to be a great medium through which interventions can be delivered in a youth-friendly environment.

Table 3.

Logistic Most Recent Use of the Internet, Internet-Using Homeless Youth (n = 194), Los Angeles, CA, 2009.

| Jobs |

Housing |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | 95% C.I. | O.R. | 95% C.I. | |||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.79 | 1.15 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 1.06 |

| Race (White = 1) | 1.05 | 0.44 | 2.54 | 1.02 | 0.34 | 3.00 |

| Years since first Homeless | 1.06 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.26* |

| Housing (Literal Homelessness = 1) | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.83* | 0.91 | 0.29 | 2.78 |

| Frequency of Internet Use | 1.06 | 0.81 | 1.38 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 1.19 |

| Last Access (Public Library = 1) | 1.01 | 0.42 | 2.45 | .958 | 0.30 | 2.99 |

| Internet Connections to | ||||||

| Parents | 1.02 | 0.42 | 2.51 | 1.01 | 0.31 | 3.34 |

| Other Family | 1.43 | 0.63 | 3.09 | 1.20 | 0.36 | 3.04 |

| Home-Based Peers | 2.57 | 1.18 | 5.62* | 1.97 | 0.67 | 5.79 |

| Case Workers | 2.94 | 0.78 | 11.09 | 6.68 | 1.68 | 26.51** |

| Potential Employers | 2.59 | 1.12 | 6.00* | 0.85 | 0.26 | 2.75 |

| −2 Log | 194.30 | 131.69 | ||||

| Nagelkkerke R2 | 0.20 | 0.15 | ||||

= p<.05,

= p<.01

Footnotes

Accepted by previous editor Maria Bakardjieva

Contributor Information

Eric Rice, University of Southern California, 1149 S. Hill St., Suite 360, Los Angeles, California, 90015.

Anamika Barman-Adhikari, University of Southern California, 669 W. 34th Street, Los Angeles, California, 90089.

References

- Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E. Sexual health information seeking online. JSSWR. 2011;2(2) doi: 10.5243/jsswr.2011.5. http://www.jsswr.org/issue/current. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baym NK, Zhang YB, Lin MC. Social interactions across media. New Media & Society. 2004;6(3):299. [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Zhang Y. Severe aggression and related conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47(1):75. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The field of cultural production, or: The economic world reversed* 1. Poetics. 1983;12(4-5):311–356. [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS. Structural holes. Harvard Univ. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Charney T, Greenberg BS. Uses and gratifications of the internet. Communication Technology and Society: Audience Adoption and Uses. 2001:379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(1):95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Copher JI, Kanfer AG, Walker MB. Everyday communication patterns of heavy and light email users. In: Wellman B, Haythornthwaite C, editors. The Internet in everyday life. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2002. pp. 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- DeSanctis G, Poole MS. Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organization Science. 1994;5(2):121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Eyrich-Garg KM. Sheltered in cyberspace? Computer use among the unsheltered street homeless. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(1):296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DA, Perse EM. The world wide web as a functional alternative to television. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2000;44(2):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Ennett S, Ringwalt C. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1406–1418. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haythornthwaite C. Strong, weak, and latent ties and the impact of new media. The Information Society. 2002;18(5):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Karabanow J, Naylor T. Being hooked up: Exploring the experiences of street youth with information communication technology. In: Looker ED, editor. Bridging and bonding across digital divides: Equity and information and communication technology. Wilfred Laurier Press; Waterloo: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukophadhyay T, Scherlis W. Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist. 1998;53(9):1017–1031. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social media & mobile Internet use among teens and young adults. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Rainie L, Lewis O. Teenage life online: The rise of the instant-message generation and the internet’s impact on friendships and family relationships. Pew Internet & American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social resources and instrumental action. In: Marsden PV, Lin N, editors. Social structure and network analysis. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1982. pp. 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections. 1999;22(1):28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Maczewski M. Exploring identities through the Internet: Youth experiences online. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2002;31(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Matei S, Ball-Rokeach SJ. Belonging across geographic and Internet spaces: Ethnic area variations. In: Wellman B, Haythornthwaite C, editors. The Internet in everyday life. Blackwell; Oxford, U.K.: 2002. pp. 404–430. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rice E, Mallet S, Rosenthal D. Cross-national variations in behavioral profiles among homeless youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;37(1):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9005-4. doi:10.1007/s10464-005-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Rice E, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Rosenthal D, Batterham P, Duan N. Adolescents exiting homelessness over two years: The risk amplification and abatement model. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(4):762–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00610.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn NG, Rosenthal D, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Batterham P, Rice E, Solorio R. Newly homeless youth typically return home. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(6):574–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D, Wolak J. Risk factors for and impact of online sexual solicitation of youth. JAMA. 2001;285(23):3011–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Wolak J, Finkelhor D. Trends in youth reports of sexual solicitations, harassment and unwanted exposure to pornography on the internet. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(2):116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DA, Melton D, Owczarzak J. PowerON: The use of instant message counseling and the internet to facilitate HIV/STD education and prevention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;77(1):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie NH, Erbring L. Internet and society. Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.bsos.umd.edu/socy/alan/webuse/handouts/Nie%20and%20Erbring-Internet%20and%20Society%20a%20Preliminary%20Report.pdf.

- Orlikowski WJ, Yates JA, Okamura K, Fujimoto M. Shaping electronic communication: The metastructuring of technology in the context of use. Organization Science. 1995:423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi Z, Rubin AM. Predictors of internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2000;44(2):175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe CJ. Encouraging sexual literacy in a Digital Age: Teens, sexuality and new media. University of Chicago; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Haase A, Wellman B, Witte JC, Hampton KN. Capitalizing on the net: Social contact, civic engagement, and sense of community. In: Wellman B, Haythornthwaite C, editors. Internet and everyday life. Blackwell; London, UK: 2002. pp. 291–324. [Google Scholar]

- Rice E. The positive role of social networks and social networking technology in the condom-using behaviors of homeless young people. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(4):588–595. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Milburn N, Rotheram-Borus M. Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Monro W, Barman-Adhikari A, Young SD. Internet use, social networking, and HIV/AIDS risk for homeless adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(6):610–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.016. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E, Stein JA, Milburn N. Countervailing social network influences on problem behaviors among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(5):625–639. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal B. From dirt road to information superhighway: Advanced information technology (AIT) and the future of the urban poor. In: Wheeler JO, Aoyama Y, Warf B, editors. Cities in the telecommunications age: The fracturing of geographies. Routledge; New York: 2000. pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KEE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(2):104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servon Lisa., Pinkett Randal D. Narrowing the digital divide: The potential and limits of the US community technology movement. In: Castells M, editor. The network society: A cross-cultural perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing, Ltd; Cheltenham, Glos: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Reich SM, Waechter N, Espinoza G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29(6):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K, Greenfield PM, Tynes B. Constructing sexuality and identity in an online teen chat room. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2004;25(6):651–666. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Johnson KD. Self-mutilation and homeless youth: The role of family abuse, street experiences, and mental disorders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13(4):457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B, Frank K. Network capital in a multi-level world: Getting support from personal communities. Social Capital: Theory and Research. 2001:233–273. [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Mitchell KJ. How do high-risk youth use the internet? Characteristics and implications for prevention. Child Maltreatment; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Nowhere to grow: Homeless and runaway adolescents and their families. Aldine de Gruyter; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in internet-and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4(4):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SD, Rice E. Online social networking technologies, HIV knowledge, and sexual risk and testing behaviors among homeless youth. AIDS and Behavior. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9810-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]