Abstract

Background:

Early diagnosis and appropriate therapy of sepsis is a daily challenge in intensive care units (ICUs) despite the advances in critical care medicine. Procalcitonin (PCT); an innovative laboratory marker, has been recently proven valuable worldwide in this regard.

Objectives:

This study was undertaken to evaluate the utility of PCT in a resource constrained country like ours when compared to the traditional inflammatory markers like C - reactive protein (CRP) to introduce PCT as a routine biochemical tool in regional hospitals.

Materials and Methods:

PCT and CRP were simultaneously measured and compared in 73 medico-surgical ICU patients according to the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) criteria based study groups.

Results:

The clinical presentation of 75% cases revealed a range of systemic inflammatory responses (SIRS). The diagnostic accuracy of PCT was higher (75%) with greater specificity (72%), sensitivity (76%), positive and negative predictive values (89% and 50%), positive likelihood ratio (2.75) as well as the smaller negative likelihood ratio (0.33). Both serum PCT and CRP values in cases with sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock were significantly higher from that of the cases with SIRS and no SIRS (P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

PCT is found to be superior to CRP in terms of accuracy in identification and to assess the severity of sepsis even though both markers cannot be used in differentiating infectious from noninfectious clinical syndrome.

Keywords: C - reactive protein, procalcitonin, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

INTRODUCTION

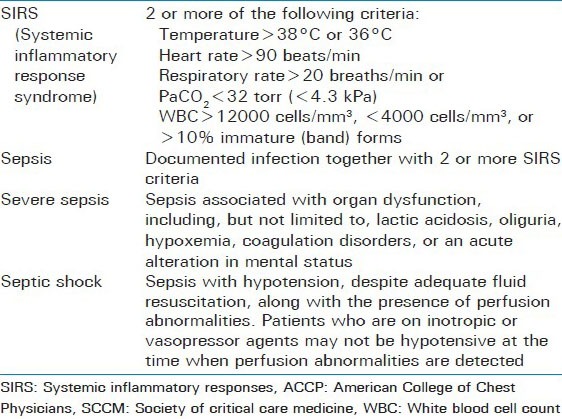

Despite the enormous investment in critical care resources, severe sepsis mortality ranges from 28% to 50% or greater. Moreover, cases of severe sepsis are expected to rise in the future for several reasons, including: Increased awareness and sensitivity for the diagnosis; increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients; wider use of invasive procedures; more resistant microorganisms; and an aging population[1] Definitions for the terms of “SIRS”, “sepsis”, “severe sepsis” or “septic shock” have been proposed by the ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference in 1992, and are now widely used. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) encompasses a variety of complex findings that result from systemic activation of the innate immune response. The clinical parameters include two or more the following: Fever (>38° C) or hypothermia (<36° C), increased heart rate (>90 beats/min), tachypnea (>20 breaths/min) or hyperventilation (PaCO2 < 32 mmHg), and altered white blood cell count (>12,000 cells/mm3 or <4000 cells/mm3) or presence of >10% immature neutrophils. Sepsis is defined as SIRS resulting from infection, whether of bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic origin. Severe sepsis is associated with at least one acute organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion, or hypotension[2,3]

Traditional markers of systemic inflammation, such as CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and white blood cell count (WBC), also have proven to be of limited utility in such patients due to their poor sensitivity and specificity for bacterial infection. Moreover, microbiological cultures; the conventional gold standard diagnostic method for sepsis, are often time consuming do not reflect the host response of systemic inflammation or the onset of organ dysfunction, and sometimes misleading with false positive or false negative reports. These shortcomings in both culture and available blood tests have driven researchers to find other more sensitive and specific markers. In recent years, PCT has been the focus of much attention as a specific and early marker for systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis, both in children and adults[3,4]

Procalcitonin is the prohormone of calcitonin, secreted by different types of cells from numerous organs in response to proinflammatory stimulation, particularly bacterial stimulation; whereas calcitonin is only produced in the C cells of the thyroid gland as a result of hormonal stimulus.[5] Depending on the clinical background, a PCT concentration above 0.1 ng/mL indicate clinically relevant bacterial infection, requiring antibiotic treatment.[6] At a PCT concentration > 0.5 ng/mL, a patient should be considered at risk of developing severe sepsis or septic shock.[7,8]

Hyperprocalcitoninemia in systemic inflammation or infection occurs within 2-4 hours, often reaches peak concentrations in 8-24 hours, and persists for as long as the inflammatory process continues. The half-life of PCT is approximately 24 hours; therefore, concentrations normalize fairly quickly with the patient's recovery. In comparison, CRP takes 12-24 hours to rise and remains elevated for up to 3 to 7 days. Because PCT concentrations increase earlier and normalize more rapidly than CRP, PCT has the potential advantage of earlier disease diagnosis, as well as better monitoring of disease progression.[9] Moreover, a number of studies have shown that the systematic use of PCT for sepsis diagnosis and monitoring may also have a positive impact on the reduction of antibiotic (AB) treatment, therefore allowing a shorter stay in the ICU and lower costs per case. This will also be beneficial in combating the increase of antibiotic-resistant micro-organisms which is mainly related to the excess use of antibiotics.[10,11,12,13] Additionally, researchers found a ≥30% decrease in PCT levels between days 2 and 3 to be an independent predictor of survival in ICU patients.[14]

Thus, procalcitonin has been identified as a promising biomarker that may provide added value to the clinical decision process, i.e. assist in diagnosis, assess prognosis, and assist in treatment selection and monitoring. This biomarker is now widely used in Europe and recently it was approved by the FDA in USA for the diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis and evaluation of the systemic inflammatory response in the clinical arena.[15] For the very first time, PCT is now commercially available in our country and is being used as a biomarker at the Apollo Hospital, Dhaka. So far to our knowledge this would be the first study done with PCT on Bangladeshi population. This study was undertaken to detect and to evaluate the level of PCT compared to other conventional methods like CRP with an aim of introducing PCT as a routine tool for treatment of sepsis in our country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Apollo Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, receiving patients from affluent to low-middle socioeconomic status emerging from the entire country. This is the first hospital in Bangladesh, accredited by the Joint Commission International Accreditation (JCIA), a subsidiary of the United States based Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO); serving the community as a high-intensity tertiary care referral center. Out of all the adult patients (>18 years of age) consecutively admitted to the mixed medico-surgical intensive care unit (ICU) of the hospital during the period of January 2011 to December 2011, 73 cases were finally included in this study. Neurosurgical, traumatized, and elective surgical patients without complications were excluded. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and care of the patients was directed by the same existing protocols.

At the time of admission and every day thereafter, signs and symptoms, clinical and laboratory data regarding PCT and CRP levels were collected along with other relevant laboratory tests according to the patient's clinical status (BT, WBC count, and arterial blood-gas analysis). The requests for PCT and CRP tests were variable in each patient (once – 12 times). PCT measurement was performed by enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (B.R.A.H.M.S.; Diagnostica AG, Hennigsdorf/Berlin, Germany)[16] and CRP by a nephelometric method (Dadebehring BN prospec 100, Germany). Appropriate samples were collected for microbiological cultures depending on the clinical symptoms.

All the study subjects were grouped according to their clinical, laboratory and bacteriological findings. According to American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine criteria[2] the patients were split into four groups and studied till recovery [Table 1]; medicosurgical patients without SIRS were included into the ‘no SIRS’ group. All data was checked and edited after collection. From the primary data obtained, tables were made and interpreted. Data are presented as incidence (%) or mean ± SD. Data was applied in the SPSS version 12 for statistical analysis.

Table 1.

SIRS and sepsis definition (ACCP/SCCM-criteria)

RESULTS

This study included a total of 73 cases; 46 (63%) males and 27 (37%) females. Average age was 28.8 ± 9.3 years. A total of 39 (53.4%) different culture positive isolates were found from 73 clinical specimens. The clinical specimens used for microbiological culture were blood (45.2%), urine (17.8%), wound swab (10.9%), pus (5.4%), ulcer exudates (6.8%) and tracheal aspirates (4.1%). The major isolate was Escherichia coli (35.8%). Mixed infection was found in 7 (9.5%), in which Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter and other microorganisms were more common.

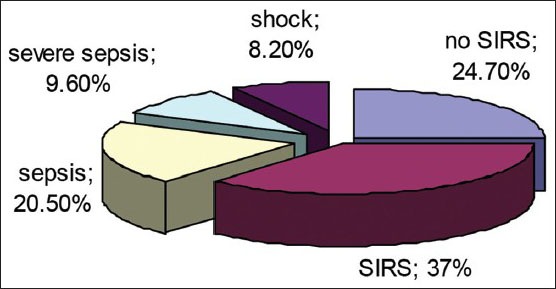

The mean PCT was 9.19 ± 13.9 ng/ml (range: 0.03-60 ng/ml); and CRP 31.4 ± 19.6 mg/l (range: 0.11-63 mg/l). The average PCT and CRP in culture positive patients was 10.9 ± 14.6 ng/ml and 34.2 ± 17.8 mg/l and in culture negative patients the value was 7.1 ± 12.8 ng/ml and 28.2 ± 21.3 mg/l, (P > 0.05) respectively. According to the clinical presentation of the patient's only18 (24.7%) patients were found to have no signs of SIRS. The rest of the cases (75.3%) presented with a range of systemic inflammatory responses [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of the study subjects according to their clinical presentation

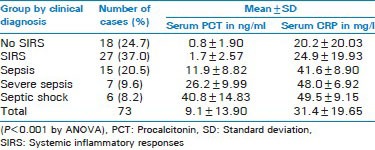

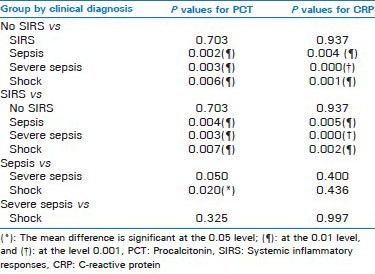

The mean serum PCT and CRP concentrations in the clinically diagnosed groups of the study subjects demonstrated highly significant difference among the groups [Table 2a]. In multiple comparison tests (Games-Howell test) both serum PCT and CRP showed significant raise of the mean values along with increased severity of the clinical presentations in the study subjects [Table 2b]. The mean PCT values in cases with sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock were significantly higher from that of the cases with SIRS and no SIRS (P < 0.01). Similar finding was observed in CRP concentration among the mentioned groups; however the level of significance was statistically higher (0.001) for severe sepsis versus SIRS and no SIRS groups. There was no significant difference of mean serum PCT and CRP values between the cases with or without SIRS or between severe sepsis group versus patients with sepsis and septic shock (P > 0.05).

Table 2a.

Serum PCT and CRP concentrations in the clinical groups of the study subjects

Table 2b.

Multiple comparisons of serum PCT and CRP concentrations between the clinical groups of the study subjects

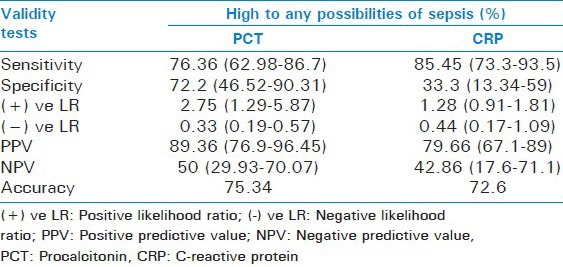

The patients with PCT level > 10 ng/ml revealed mortality rate of 16.6%; the remainder of the patients showed adequate evolution with a tendency of getting better. The average hospital stay was 8.2 days. As shown in Table 3, the sensitivity of CRP was the highest of all. However, PCT shows the highest level of accuracy (75.34%) with greater specificity, positive and negative predictive values, positive likelihood ratio as well as the smaller negative likelihood ratio. Microbiological culture results reveal 53.42% accuracy with higher specificity (50%) than CRP.

Table 3.

Comparison of the validity tests of PCT, CRP in the diagnosis of high to any possibilities of sepsis (overall)

DISCUSSION

PCT was first described as a marker of the extent and course of systemic inflammatory response to bacterial and fungal infections in 1993 by Assicot.[13] Ever since then Procalcitonin (PCT) has been examined extensively as a marker for systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis, both singularly and in combination with other markers such as CRP, in adults and children in ICU setup. The predominant assay used in most studies has been an immunoluminometric assay, called the LUMItest, manufactured by Brahms. In recent years immunofluorescent assays were given preference. The only study reported in our country earlier was conducted on neonatal sepsis using a rapid semi quantitative immunochromatographic method.[17] The quantitative immunofluorescent assay is being practiced for the first time in this study.

In this study, cultures were positive in 53.4% of microbiological culture specimens (n = 39); E. coli being the major (35.8%) isolate followed by Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter. This was in accordance with the reports of Karlsson et al.[18] and Andreola et al.[19] though the rate of positive culture was less than ours. Karlsson et al.[18] also reported of significantly higher PCT levels in positive culture cases compared to that of the negative ones. In our observation, both PCT and CRP levels were higher in cases with positive cultures though statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). In another Korean study the higher CRP levels associated with positive cultures showed greater statistical significance (P < 0.001) than PCT levels (P < 0.05).[20]

In the present study, plasma levels of PCT and CRP in patients with and without infection at different levels of SIRS were assessed. Patients with moderate to severe sepsis had higher PCT concentrations than patients with no/local infections (P < 0.01). The most recent studies with such reports are given by López et al.[21], Ruiz-Alvarez et al.[22], and Endo et al.[23]

Both serum PCT and CRP showed significant raise of the mean values along with increased severity of the clinical presentations in the study subjects. Significantly higher mean PCT and CRP values were observed in sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock cases compared to SIRS and no SIRS when compared at the various severities of systemic inflammation and sepsis. However, a number of studies having not been able to demonstrate significant relations of PCT or CRP with severity raised controversies regarding their utility as prognostic markers[24] In this study the mortality was confined to the cases with PCT level of > 10 ng/ml even though the rate of mortality was low (16.6%)[21]

With regards to the diagnostic performance of PCT, various international literatures found PCT to be a useful marker in the diagnosis of a septic process with a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 94% comparing these values with CRP[25,26,27,28] These studies have a more precise methodology towards the desired objectives and the sample number is much greater for which the statistical significance was much better. In this study PCT showed highest level of accuracy (75.34%) with greater specificity (72.2%), positive and negative predictive values, positive likelihood ratio as well as the smaller negative likelihood ratio. However, sensitivity of CRP in the diagnosis of sepsis was found to be higher (85.45%) than PCT (76.36%). By convention, marked changes in prior disease probability can be assumed in PLR exceeding 10.0 and NLR below 0.1[29] Procalcitonin had a higher PLR and lower NLR than did CRP and complement proteins. These results are in agreement with those of Clec’h et al.[28], Ruiz-Alvarez et al.[22] and others.[25,26,27]

Few studies have reported of lower diagnostic performance of PCT than CRP in differentiating between sepsis and SIRS.[30,31,32] In contrast to this, majority of studies have reported that procalcitonin was a better marker to estimate the severity, prognosis, or further course of the sepsis[10,26,33,34] This study was consistent to the others with a few minor limitations. First, serial PCT monitoring every day was avoided which may improve its performance as an aid for follow up of sepsis. Second, antimicrobial therapy may have an impact on PCT values which could not be explained with our study design.

CONCLUSIONS

Rapid identification of infection has a major impact on the clinical course, management, and outcome of critically ill intensive care unit (ICU) patients. In this study both PCT and CRP showed limited diagnostic value in critical patients in terms of identifying infectious origins. However, procalcitonin is superior to C-reactive protein as marker of clinical severity. Procalcitonin should be included in diagnostic guidelines for sepsis and in clinical practice in intensive care units in our country. However, further large scale studies are recommended to evaluate the diagnostic as well as prognostic utility of PCT in ICU setting of tertiary care hospitals in Bangladesh.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfafflin A, Schleicher E. Inflammation markers in point-of-care testing (POCT) Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;393:1473–80. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitaka C. Clinical laboratory differentiation of infectious versus noninfectious systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;351:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meisner M. Pathobiochemistry and clinical use of procalcitonin. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;323:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker KL, Snider R, Nylen ES. Procalcitonin assay in systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis: Clinical utility and limitations. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:941–52. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318165BABB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chua AP, Lee KH. Procalcitonin in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) J Infect. 2004;48:303–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cone JB. Inflammation. Am J Surg. 2001;182:558–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luster AD. Chemokines-chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:436–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, Saint-Louis P, Lacroix J. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:206–17. doi: 10.1086/421997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whicher J, Bienvenu J, Monneret G. Procalcitonin as an acute phase marker. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001;38:483–93. doi: 10.1177/000456320103800505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, de Vries EG, Koops HS, Groothuis GM, et al. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:458–61. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993;341:515–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90277-N. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunkhorst FM, Al-Nawas B, Krummenauer F, Forycki ZF, Shah PM. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and APACHE II score for risk evaluation in patients with severe pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:93–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oberhoffer M, Vogelsang H, Russwurm S, Hartung T, Reinhart K. Outcome prediction by traditional and new markers of inflammation in patients with sepsis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:363–8. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Instruction Manual (version 4.0us) article number: 825.050: Immunofluorescent assay for the determination of PCT (procalcitonin) in human serum and plasma. BRAHMS PCT sensitive KRYPTOR 2008 (Hennigsdorf, Germany) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naher BS, Mannan MA, Noor K, Shahiddullah M. Role of serum procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2011;37:40–46. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v37i2.8432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson S, Heikkinen M, Pettilä V, Alila S, Väisänen S, Pulkki K, et al. Predictive value of procalcitonin decrease in patients with severe sepsis: A prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R205. doi: 10.1186/cc9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreola B, Bressan S, Callegaro S, Liverani A, Plebani M, Da Dalt L. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as diagnostic markers of severe bacterial infections in febrile infants and children in the emergency department. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:672–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31806215e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hur M, Moon HW, Yun YM, Kim KH, Kim HS, Lee KM. Comparison of diagnostic utility between procalcitonin and c-reactive protein for the patients with blood culture-positive sepsis. Korean J Lab Med. 2009;29:529–35. doi: 10.3343/kjlm.2009.29.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López FR, Jiménez AE, Tobon GC, Mote JD, Farías ON. Procalcitonin (PCT), C reactive protein (CRP) and its correlation with severity in early sepsis. Clin Rev Opin. 2011;3:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Alvarez MJ, Garcıxa-Valdecasas S, De Pablo R, Saxnchez Garcıxa M, Coca C, Groeneveld TW, et al. Diagnostic efficacy and prognostic value of serum procalcitonin concentration in patients with suspected sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:63–71. doi: 10.1177/0885066608327095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endo S, Aikawa N, Fujishima S, Sekine I, Kogawa K, Yamamoto Y, et al. Usefulness of procalcitonin serum level for the discrimination of severe sepsis from sepsis: A multicenter prospective study. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:244–9. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettilä V, Pentti J, Pettilä M. Predictive value of antithrombin III and serum C-reactive protein concentration in critically ill patients with suspected sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:271–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, Pittet D, Ricou B, Grau GE, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6 and interleukin- 8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:396–402. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2009052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castelli GP, Pognani C, Cita M, Stuani A, Sgarbi L, Paladini R. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, white blood cells and SOFA score in ICU: Diagnosis and monitoring of sepsis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2006;72:69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luzzani A, Polati E, Dorizzi R, Rungatscher A, Pavan R, Merlini A. Comparison of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1737–41. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063440.19188.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clec’h C, Fosse JP, Karoubi P, Vincent F, Chouahi I, Hamza L, et al. Differential diagnostic value of procalcitonin in surgical and medical patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:102–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000195012.54682.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence. Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ugarte H, Silva E, Mercan D, DeMendonca A, Vincent JL. Procalcitonin used as a marker of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:498–504. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199903000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suprin E, Camus C, Gacouin A, Le Tulzo Y, Lavoue S, Feuillu A. Procalcitonin: A valuable indicator of infection in a medical ICU? Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1232–8. doi: 10.1007/s001340000580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang BM, Eslick GD, Craig JC, McLean AS. Accuracy of procalcitonin for sepsis diagnosis in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:210–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70052-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sponholz C, Sakr Y, Reinhart K, Brunkhorst F. Diagnostic value and prognostic implications of serum procalcitonin after cardiac surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Crit Care. 2006:101–11. doi: 10.1186/cc5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowther FB, Rodrigues CS, Deshmukh MS, Kapadia FN, Hegde A, Mehta AP, et al. Prospective comparison of eubacterial PCR and measurement of procalcitonin levels with blood culture for diagnosing septicemia in intensive care unit patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2964–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00418-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]