Abstract

The continuing advances in the biochemical research for the discovering an ideal biomarker for diagnosing myocardial injury have led to discovery cardiac Troponin, a biochemical gold standard for myocardial necrosis. Further with advances in the immunoassay techniques, the 99th percentile cutoff value of cardiac troponin required for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction decreased, with the latest available ultrasensitive cardiac troponin assay capable of measuring level as low as 0.005 ng/ml. Troponin have both diagnostic as well as prognostic significance in myocardial necrosis, but the cut off value by 99th percentile rule is useful only when applied to patients with a high pretest probability of Acute Coronary Syndrome(ACS) and also the results must be interpreted in the context of clinical history, ECG findings, and possibly cardiac imaging to establish the correct diagnosis. As cardiac troponins are also elevated in other cardiac conditions such as cardiomyopaties, the serial monitoring of the cardiac troponin level along with the absolute value would help to differentiate myocardial infarction from these many varied conditions, with the interval of serial assay being reduced to 3 hours. The aim of this review is to complement the advantages, to emphasize on proper interpretation of positive results, to appraise the challenges faced with the available cardiac troponin assays and need for further research to overcome them and build up the most ideal cardiac marker for diagnosing the myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, cardiac troponin, myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Since 1954, the search for a defining cardiac biomarker began as the breakdown products of myocardial ischemia were discovered. The ideal marker would be effective and accurate would indicate how severe and when an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has occurred. Thus far, no single marker can fulfill all criteria, but troponins can be very useful in making an important clinical decision to admit or discharge a patient in the emergency room (ER) or to treat a patient on the inpatient ground.[1] The first fundamental investigations of troponin were performed in the laboratories of S. Ebashi, J. Gergely, and S. V. Perry. Troponin consists of three components, each of which performs specific functions. Troponin C binds Ca2+, troponin I inhibits the ATPase activity of actomyosin, and troponin T provides for the binding of troponin to tropomyosin.[2]

In addition to fundamental interest, investigation of troponin is also important from the practical point of view. For example, components of troponin are widely used as biochemical markers of various heart pathologies.[1] According to the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force 2012 for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction, in addition to clinical symptoms of ischemia, detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarker values (preferably cardiac troponin (cTn) with at least one value above the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL)) is required for diagnosis of AMI, although the WHO criteria differs by requiring above the 95th percentile. Lower cutoff values for troponin can identify the population at risk for cardiac events, providing risk stratification rather than simple “infarction or not” categories. A barrier to achieving these lower cutoff limits for troponin is the lack of standardization among the troponin assays, due to: 1) assays with varying stabilities, 2) different antibody configurations recognizing different epitopes, and 3) different coefficients of variability. With this lack of standardization in assays, relaxing cutoff values could result in an increase of false-positives.[3]

The main goal of this review is to summarize the role of troponins in emergency medicine and its utility as a point of care test (POCT).

cTn testing is an essential part of the diagnostic workup and management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). For the last 15 years, the ever-increasing sensitivity of cTn assays has had a dramatic impact on the use of cTn testing to diagnose ACS.[4] The results of cTn testing guide the decision for coronary intervention. However, although the increasing sensitivity of cTn assays lowers the number of potentially missed ACS diagnoses, it presents a diagnostic challenge because the gains in diagnostic sensitivity have inevitably come with a decrease in specificity. For instance, the replacement of the cTn assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) by the more sensitive TnI-Ultra assay in the Brigham and Women's Hospital Clinical Laboratories in early 2007 resulted in a doubling of positive cTn results in samples collected in the emergency department, even though there was no change in the frequency of final diagnoses of ACS.[5]

UTILITY AND ROLE OF HIGH-SENSITIVITY TROPONIN TEST

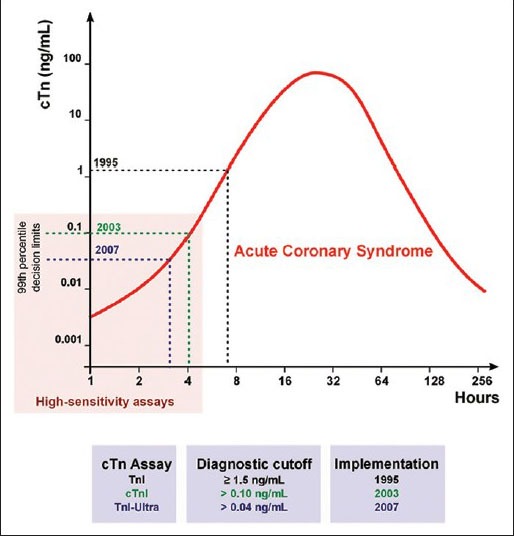

Rapid advances in immunoassay technology and the international adoption of traceable troponin calibration standards have allowed manufacturers to develop and calibrate troponin assays with magnificent analytic sensitivity and precision. Thus, a contemporary cTnI assay such as TnI-Ultra detects plasma cTn levels as low as 0.006 ng/mL with an assay range of 0.006-50 ng/mL. The limit of detection of a contemporary cTnT assay (ElecsysTnT-hs, Roche Diagnostics) is as low as 0.005 ng/mL. From 1995-2007, the limit of detection fell from 0.5 ng/mL for some cTn assays to 0.006 ng/mL like TnI Ultra, an >100-fold improvement in analytic sensitivity [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Evolution of the cardiac troponin (cTn) assays and their diagnostic cutoffs. A hypothetical case of acute coronary syndrome is depicted with the earliest times of potential diagnosis corresponding to the diagnostic cutoffs of more sensitive cTn assays. The years correspond to the availability of the respective assays in the US market

The use of contemporary high-sensitivity cTn assays makes it possible to detect low levels of cTn even in plasma from healthy subjects. High-sensitivity cTn assays are designated as such on the basis of their ability to detect cTns even in healthy individuals.[6] The latest generation of high-sensitivity cTn assays can detect cTn in >95% of a reference population. Therefore it is imperative to define a clinical decision limit for cTn concentration, that is, a “positive” cTn result.

INTERPRETATION OF “THE 99TH PERCENTILE RULE”

As per the third universal definition of myocardial infarction, 2012, detection of a rise and/or fall of the measurements is essential to the diagnosis of acute MI.[7] An increased cTn concentration is defined as a value exceeding the 99th percentile (with optimal precision defined by total coefficient of variation (CV) <10%) of a normal reference population (URL). This discriminatory 99th percentile is designated as the decision level for the diagnosis of MI and must be determined for each specific assay with appropriate quality control in each laboratory.[3] This guideline provides the framework for determining the decision limit or a “positive” troponin result.

Based on the 99th percentile rule, troponin decision limits of several high-sensitivity cTn assays can be set as low as 0.01 ng/mL.[7] This makes it possible to identify patients with ACS earlier, enabling earlier coronary intervention. However, the improving clinical sensitivity has come at the cost of reduced specificity, thus presenting an additional diagnostic challenge for clinicians.

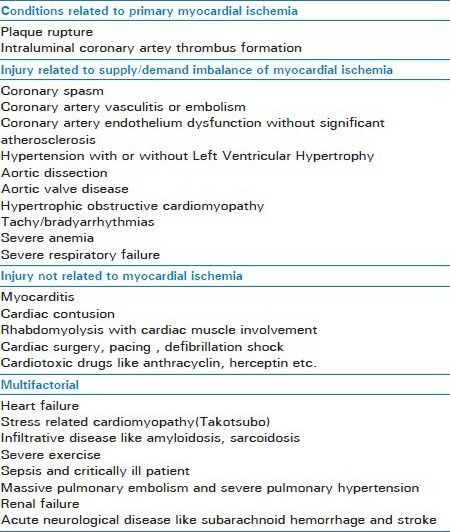

The cutoff value by 99th percentile rule is useful only when applied to patients with a high pretest probability of ACS. The clinician must interpret cTn results in the context of clinical history, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, and possibly cardiac imaging to establish the correct diagnosis. A positive troponin in the setting of a low pretest probability for ACS may lead to increase in false positive results. Unfortunately, in order to avoid malpractice, many clinicians are compelled to order comprehensive panels of laboratory tests, including cTn, for patients with a very low pretest probability of ACS, which adversely affects the positive predictive value of cTn assays for diagnosing myocardial infarction. The traditional statement, before the advent of high-sensitivity cTn assays, held that troponins do not appear in the circulation of individuals with a healthy myocardium. However, with high-sensitivity troponin assays, circulating cTnT or cTnI can be found in the plasma as a result of transient ischemic or inflammatory myocardial injury. Thus, elevated cTn may be detected in conditions other than ACS [Table 1], including heart failure, cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, renal failure, tachyarrhythmia, and pulmonary embolism, and even after strenuous exercise in healthy individuals.[8]

Table 1.

Causes of elevated troponin

REQUIREMENT OF SERIAL TROPONIN TESTING

The absolute level of cTn in plasma or serum above the decision limit is a very important component for diagnosis of ACS. Though absolute level cTn is found raised seen in multiple chronic cardiac and noncardiac conditions, but the trend of a rise or fall in serial cTn levels strongly supports an acutely evolving cardiac injury such as, most commonly, acute myocardial infarction. During the past years when the lower-sensitivity, lower-precision cTn assays were available, clinician often had to wait for an average of 6 h to see such conclusive increase. But now with availability of high sensitivity cTn assay, an interval of mere 2-3 h can be highly informative. As it is very much important for early diagnosis of ACS and appropriate emergency intervention, as well as the ease of performing this relatively inexpensive assay, clinicians do not need to wait for 6-8 h before ordering second troponin test to rule in ACS. Mahajan and Jarolim[9] recommend collecting a second specimen for cTn testing within 2-3 h from the collection of the blood sample at presentation to help confirm the diagnosis of MI.

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Although the new generation troponins have revolutionized the diagnosis and management of ACS, still there are many challenges to face and overcome.

Challenge ahead of the laboratorian and clinician

With the rapid ongoing advances in cTn assays, defining an appropriate terminology so as to categorize past, present, and future assays in a manner that integrates all facets of performance and will be useful is not that straight forward.

Challenge ahead because of lack of well-defined “normal reference population”

As per the guidelines that establish the 99th percentile of “a normal reference population” as the diagnostic decision limit for MI,[3] consistent guidelines for what constitutes a “normal reference population” have not been established. Eggers and colleagues[10] have confirmed that how the selection of the reference population is done would strongly influence the determination of the 99th percentile value, even amongst the apparently healthy individuals.[11] Thus, 99th percentile value of “a normal reference population would differ if the population used for deriving the value is either apparently normal individual or visitors to emergency with noncardiac chest pain or stable subclinical structural heart disease.

Challenge ahead because of nonspecific binding of cTn at its low level

With the availability of high sensitivity cTn assays which detects very low cTn levels, the problem of nonspecific binding of cTn with serum or plasma constituents prevails. The same was proved by Wu et al.,[12] who observed low-level nonspecific binding in up to 25% of samples with results below the lower limit of quantification, with one of 20 samples having a quantifiable result. He further, concluded that given the very low level of binding, the overall specificity of the assay tested was maintained. This influence, however, will be inherently accounted for during determination of the 99th percentile in reference populations.

Challenge ahead because of biological variation in cTn concentration

As the limit of detection of cTn concentration moves orders of magnitude lower, biological variation both within-day and between-day was recognized. Similarly, a study designed by Wu and colleagues, for healthy individuals biological variation in cTn concentration have also shown CVs of 9.7 and 14.1%, respectively, within-day and between-day intraindividual levels. Further, this magnitude of variation was similar to the analytical CV and was <40% of the total CV for this population. Thus, it is seen that the intraindividual variation within a stable healthy population appears to be small relative to the differences between individuals. This important finding supports the concept that at very low concentrations, assessment of serial changes in the individual patient will be more useful than applying a general population-based reference cutoff.

CONCLUSION

With the availability and use of higher-sensitivity cTn assays into clinical practice, the number of patients who present with ACS and have diagnosed MI will increase exactly similar to issues faced during the transition from the use of creatine kinase MB to cTn[13]

For diagnostic as well as the therapeutic implications of low cTn concentrations into clinical practice, the above said limitations should be taken into due consideration until further studies formulated to provide evidence-based answer for the same limitations are completed in future and clinical practice guidelines and performance measures derived from such studies become available

The epidemiology of MI, including its incidence and fatality rates, as well as societal implications for insurance and employment is needed to be taken into consideration while considering the therapeutic implications of low cTn concentrations

At present, on the basis of the prior experience with each evaluation of lower decision limits to date,[14] we expect that treatment with potent antithrombotic therapy and coronary intervention will benefit patients with a clinical syndrome consistent with ACS and an abnormal result in a high-sensitivity assay. But, will hospitalization be necessary for those patients with a low clinical probability of ACS and a positive result in a high-sensitivity cTn assay, or will algorithms be developed that will allow for safe outpatient evaluation with close follow-up, is yet needed to be formulated

The application of assays with lower limits of detection also has led predictably to increases in the proportion of patients evaluated in the emergency setting who have detectable cTn concentrations in a variety of acute and chronic medical conditions other than ACS.[4] From a prognostic perspective, it is noteworthy that in most of the settings studied to date, patients presenting with an increased cTn concentration have had poorer prognoses than those without detectable cTn

Also a deeper understanding of the potential sources of “normal” and pathologic variation between and within patients that become relevant only at the very low cTn concentrations detected with the new assays needs to be studied

Due to the epidemiological variation, each epidemiologically varied regions must conduct studies for detecting the absolute level as well as serial cTn levels both in the acute as well as chronic myocardial as well as other medical conditions to conclusively gather data for formulating respective evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, which to some extent can prove to overcome some of the said challenges.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajappa M, Sharma A. Biomarkers of cardiac injury: An update. Angiol. 2005;56:677–91. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filatov VL1, Katrukha AG, Bulargina TV, Gusev NB. Troponin: structure, properties, and mechanism of functioning. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1999 Sep;64:969–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD. Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melanson SE, Morrow DA, Jarolim P. Earlier detection of myocardial injury in a preliminary evaluation using a new troponin I assay with improved sensitivity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:282–6. doi: 10.1309/Q9W5HJTT24GQCXXX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melanson SE, Conrad MJ, Mosammaparast N, Jarolim P. Implementation of a highly sensitive cardiac troponin I assay: Test volumes, positivity rates and interpretation of results. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;395:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apple FS. A new season for cardiac troponin assays: It's time to keep a scorecard. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1303–6. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.128363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apple FS, Parvin CA, Buechler KF, Christenson RH, Wu AH, Jaffe AS. Validation of the 99th percentile cutoff independent of assay imprecision (CV) for cardiac troponin monitoring for ruling out myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2198–200. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffe AS, Babuin L, Apple FS. Biomarkers in acute cardiac disease: The present and the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahajan VS, Jarolim P. How to interpret elevated cardiac troponin levels. Circulation. 2011;124:2350–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggers KM, Jaffe AS, Lind L, Venge P, Lindahl B. Value of cardiac troponin I cutoff concentrations below the 99th percentile for clinical decision making. Clin Chem. 2008;55:85–92. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.101683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace TW, Abdullah SM, Drazner MH, Das SR, Khera A, McGuire DK, et al. Prevalence and determinants of troponin T elevation in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113:1958–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu AH, Agee SJ, Lu QA, Todd J, Jaffe AS. Specificity of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay using single-molecule-counting technology. Clin Chem. 2009;55:196–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.108837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Myocardial infarction redefined-a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–69. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Storrow AB, et al. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines: Clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:552–74. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]