Abstract

Our previous studies on the transmembrane domain of human integrin subunits have shown that a conserved basic amino acid in both subunits of integrin heterodimers is positioned in the plasma membrane in the absence of interacting proteins. To investigate the possible functional role of the lipid-embedded lysine in the mouse integrin β1 subunit, this amino acid was replaced with leucine, and the mutated β1 subunit (β1AK756L) was stably expressed in β1-deficient GD25 cells. The extracellular domain of β1AK756L integrins possesses a competent conformation for ligand binding as determined by the ability to mediate cell adhesion, and by the presence of the monoclonal antibody 9EG7 epitope. However, the spreading of GD25-β1AK756L cells on fibronectin and laminin-1 was impaired, and the rate of migration of GD25-β1AK756L cells on fibronectin was reduced compared with GD25-β1A cells. Phosphorylation of tyrosines in focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and the Y416 in c-Src in response to β1AK756L-mediated adhesion was similar to that induced by wild-type β1. The tyrosine phosphorylation level of paxillin, a downstream target of FAK/Src, was unaffected by the β1 mutation, whereas tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS was strongly reduced. The results demonstrate that CAS is a target for phosphorylation both by FAK-dependent and -independent pathways after integrin ligation. The latter pathway was inhibited by wortmannin and LY294002, implicating that it required an active phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Furthermore, the K756L mutation in the β1 subunit was found to interfere with β1-induced activation of Akt. The results from this study identify phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase as an early component of a FAK-independent integrin signaling pathway triggered by the membrane proximal part of the β1 subunit.

INTRODUCTION

Signals from the extracellular matrix (ECM) that regulate the proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival of adherent cells are mainly mediated by integrins. The integrin family consists of a large number of receptors composed of transmembrane α and β subunits (Hynes, 1992). The short cytoplasmic tails of integrins connect ECM to the actin cytoskeleton and to cell signaling machinery (Hibbs et al., 1991; LaFlamme et al., 1994; O'Toole et al., 1994; Leong et al., 1995). Depending on the composition of the ECM, assembly of complexes of signaling proteins and specific integrins leads to activation of a variety of signaling pathways, often coordinately regulated by growth factors (Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999). ECM engagement by most integrins leads to the activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Cary and Guan, 1999). In addition to the activation of FAK, other less characterized tyrosine kinases have been reported to become activated after integrin-mediated adhesion (Lewis et al., 1996; Yan and Berton, 1998; Yang et al., 1999; Obergfell et al., 2002). The molecular events that lead to FAK activation (autophosphorylation) after integrin ligand binding are not understood, but they are known to require integrin clustering, the NPXY motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of integrin β subunits, and a functional actin filament system (Burridge et al., 1992; Miyamoto et al., 1995a,b; Wennerberg et al., 2000). After integrin clustering, the autophosphorylation of Tyr-397 in FAK creates a binding site for the Src homology 2 domain of Src family kinases that promotes further phosphorylation of FAK and focal adhesion components such as paxillin and Crk-associated substrate (CAS) (Eide et al., 1995; Schlaepfer and Hunter, 1996; Richardson et al., 1997; Tachibana et al., 1997). FAK, its downstream target CAS, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) have been shown to be key mediators of integrin-mediated cell migration (Cary et al., 1996, 1998; Klemke et al., 1998; Reiske et al., 1999; Bakin et al., 2000). Tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS results in recruitment of CrkII and DOCK180, the subsequent activation of the small GTPase Rac1, and a number of downstream responses such as activation of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase cascade, remodeling of actin cytoskeleton and promotion of cell motility (Vuori et al., 1996; Dolfi et al., 1998; Kiyokawa et al., 1998a,b).

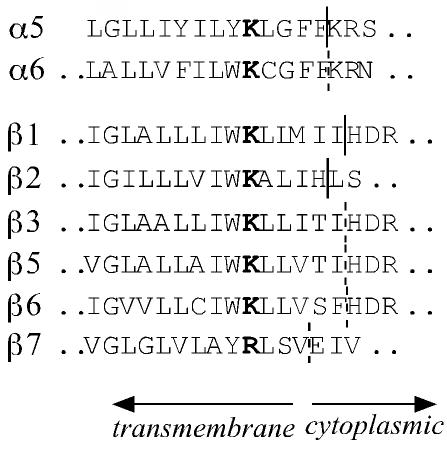

The mechanism by which integrins transfer signals across the plasma membrane involves ligand-induced conformational changes as well as receptor clustering, in which the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of integrins have central roles (Miyamoto et al., 1995a,b; Takagi et al., 2001; Takagi et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003). Consistent with this view, the amino acid sequence of the β1 subunit from sponge to human is particularly well conserved in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (Brower et al., 1997). Although the functional importance of the cytoplasmic domain of the β1subunit has been extensively studied, only a few studies have addressed the role of the transmembrane domain in integrin function (Hayashi et al., 1990; Briesewitz et al., 1996; Li et al., 2003). A striking feature of transmembrane domains of integrin subunits is the presence of a strictly conserved basic amino acid. In all known α and β subunits, the transmembrane domain contains a lysine (or arginine in two cases) after a long stretch of hydrophobic amino acids, followed again by five to six hydrophobic residues (Figure 1). Our previous work showed that the lysine (e.g., K756 in mouse β1) is positioned in the plasma membrane in absence of interacting proteins (Armulik et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences at the membrane/cytoplasm interface of the selected integrin chains. The conserved transmembrane lysine is in bold. The border between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of integrin α5, β1, and β2 has been determined experimentally (Armulik et al., 1999) and was extrapolated for the other subunits.

To investigate the functional role of this conserved unusual arrangement, we replaced the lysine in the transmembrane domain with leucine and expressed the mutated β1 subunit in β1-deficient GD25 cells. The mutation interfered with cell spreading and migration and caused strongly reduced phosphorylation of CAS and the PI3K effector PKB/Akt. These results indicate the presence of an uncharacterized PI3K-dependent signaling pathway triggered by β1 integrins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and Reagents

DNA restriction and modifying enzymes were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). A cDNA construct coding for glutathione S-transferase (GST) fused with an 80-kDa integrin-binding fragment of invasin was kindly provided by Dr. M. Fällman (Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden). Invasin binds selectively to a subset of β1 integrins and efficiently promotes cell spreading and assembly of focal adhesions (Isberg and Leong, 1990; Gustavsson et al., 2002). The GST-fusion protein was purified from Escherichia coli cultures as described previously (Klint et al., 1995). Fibronectin (FN) and vitronectin were purified from human plasma as described previously (Yatohgo et al., 1988; Smilenov et al., 1992). Mouse EHS laminin was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The GRGDS peptide was obtained from Bachem Feinechemikalen AG. Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B and glutathione-Sepharose CL were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). The PI3K inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), respectively.

Antibodies

The rabbit anti-rat β1 serum was prepared in our laboratory and has been described previously (Bottger et al., 1989). The monoclonal antibody (mAb) GoH3 against integrin subunit α6 was generously provided by Dr. A. Sonnenberg (The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Monoclonal antibodies against the following proteins were purchased: mouse β1 (clone HMβ1-1), rat β1 (clones Ha2/5 and 9EG7), mouse α5 (clone MFR5) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); chicken FAK (clone 77), chicken paxillin (clone 399), rat CAS (clone 21), phosphotyrosine (PY-99 and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated RC-20) (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), mouse c-Src (clone H-12) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and human vinculin (clone hVIN-1) (Sigma-Aldrich). Polyclonal rabbit antibodies against the following proteins/epitopes were used: human Akt1/2 (H-136) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FAK phosphotyrosine-397 and FAK phosphotyrosine-576 (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA), and Akt phosphoserine-473 and Src family phosphotyrosine 416 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Rabbit anti-mouse IgG (H+L) and fluorochrome-labeled (fluorescein isothiocyanate and Cy3) secondary goat antibodies (anti-mouse, anti-rat, and anti-rabbit IgG) were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Amersham Biosciences.

Mutation of β1A

The mutation K756L was introduced into the integrin β1A subunit by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the gel-purified BglII-XbaI fragment from pUHD10-3 expression vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) containing a doxycycline-regulated cytomegalovirus promoter upstream of a cDNA for mouse β1A (pTetβ1A) was cloned into pSP70 (Promega). The pSP70β1A(BglII-XbaI) was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction by using the following primers: K756L:1 (5′-CCTTGCTGCTGATTTGGTTACTTTTAATGATAATTC-3′), and K756L:2 (5′-GAATTATCATTAAAAGTAACCAAATCAGCAGCAAGG-3′). Mutated base pairs are in bold. The generation of the mutation was verified by DNA sequencing. The BglII-XbaI fragment of β1A carrying the mutation was cloned into the BglII-XbaI site of pTetβ1A and sequenced.

Cells

The integrin β1-deficient GD25 cell line, its subclone GD25T, which was established by stable transfection with the Tet repressor-encoding vector pUHD15–1hyg, and GD25 cells expressing wild-type β1A and β1AYY783,795FF have been described previously (Svineng and Johansson, 1999; Wennerberg et al., 2000). The GD25T cells were transfected with linearized pTetβ1AK756L and pPGKpuro vectors by using Superfect (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's recommendations. Culture medium containing 10 μg/ml puromycin was added to the transfected cells 48 h posttransfection. Surviving clones were tested for expression of β1 by flow cytometry, and clones expressing high surface levels of β1 were expanded. The GD25 cells were continuously cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and hygromycin B (100 μg/ml). The GD25 cells expressing the integrin β1 subunit were cultured in the same medium with the addition of puromycin (20 μg/ml). Experiments were performed using clones expressing similar levels of mutated β1A or wild-type β1A on the cell surface. The expression of β1A on the cell surface was verified by flow cytometry throughout the time course of these studies.

Flow Cytometry

The cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and sequentially incubated with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Antibodies were diluted in 10% goat serum in PBS containing 0.01% NaN3. Before adding a fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody the cells were washed twice with PBS. Alternatively, the cells were harvested and resuspended in Tris buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5% bovines serum albumin [BSA]) containing 2 mM EDTA and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with Tris-buffer and incubated in the same buffer containing 0.3 mM MnCl2 at 37°C for 10 min, followed by incubation with mAbs Ha2/5 or 9EG7 on ice for 1 h. Finally, after washing, the cells were incubated with fluorescein-labeled secondary antibodies and analyzed (10,000/sample) in a FACScan (BD Biosciences).

Cell Attachment and Cell Spreading Assays

The cell attachment assay was carried out in 96-well microtiter plates (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL) as described previously (Wennerberg et al., 1996). Briefly, cells (1 × 105 in 100 μl) were added to each well and allowed to attach to ECM proteins for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All samples were assayed in triplicate, and the background attachment to BSA was subtracted from all measurements. To quantify cell spreading, cells were plated on eight-well chamber slides (Falcon Plastics, Oxnard, CA) precoated with extracellular matrix proteins and allowed to attach for 30 and 60 min at 37°C. The wells were washed with PBS, and the cells were fixed in 96% ethanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The samples were photographed, and the percentage of spread cells in three microscopic fields was calculated.

Transmembrane Migration Assay

Cells were starved for 24 h in serum-free DMEM and detached by trypsin-EDTA treatment. A polycarbonate membrane (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) was coated on both sides with 50 μg/ml FN in PBS, blocked by incubation in 1% heat-treated BSA, and subsequently rinsed with PBS before mounting in a 96-well migration chamber (Neuro Probe). In lower chambers, 115 μl of serum-free DMEM or DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum was added; upper chambers contained cells (1 × 105) in serum-free DMEM and, where indicated, the GRGDS peptide (10 or 25 μg/ml). The cells were allowed to migrate for 12 h at 37°C, and cells remaining on the upper side of the membrane were removed by scraping. Subsequently, the membrane was fixed in 96% ethanol for 10 min, stained with 1% crystal violet in water for 40 min, and washed with water. The amount of stained cells at the lower side of the membrane was quantified by scanning the filter using the Molecular Analyst 2.1 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Immunoprecipitations and Western Blotting

Cells were trypsinized, washed once with serum-free DMEM, plated on cell culture dishes coated with anti-β1 mAb Ha2/5, GST-invasin, or with ECM proteins and incubated at 37°C for 1 h, unless indicated otherwise. As a negative control, cells were kept in suspension. Where indicated, cells were preincubated with LY294002 (20 μM), wortmannin (100 nM), or with dimethyl sulfoxide at room temperature (RT) for 30 min before plating on substrates. For immunoprecipitations, cells were lysed on ice for 10 min in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 30 mM Na4P2O7, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 200 μM Na3VO4, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. After preclearing the cell lysates with protein A-Sepharose, the primary antibodies were added to the samples and incubated overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the bridging antibody (rabbit anti-mouse IgG) was added to each sample and incubated for 30 min at 4°C, and for an additional 30-min period after addition of protein A-Sepharose. The protein A-Sepharose was collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was washed three times with lysis buffer. Alternatively, the cells were lysed directly in SDS sample buffer containing 40 μM dithiothreitol. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by wet electrophoretic transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). Filters were incubated with primary antibody and secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences), followed by exposure to Fuji Super RX film. Where indicated, filters were stripped in 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 2% SDS, and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 30 min at 50°C and reprobed with relevant antibodies. Protein bands were scanned and selected bands were quantified using the Molecular Analyst 2.1 software (Bio-Rad). Results presented in figures in each case originate from one gel. In some cases, the lanes not adding any essential information were removed.

Immunocytochemistry

Eight-well chamber slides (Falcon Plastics) were coated with ECM proteins overnight at 4°C and blocked with 1% BSA (heat-treated) in PBS for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were trypsinized, washed once with serum-free DMEM, and plated on the chamber slides in serum-free DMEM. In some experiments, the GRGDS peptide was added (final concentration 0.2 mg/ml) to the medium. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 1–2 h, fixed with 2 or 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min at RT, and blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS overnight at 4°C. The samples were subsequently incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in 10% goat serum in PBS. Actin cytoskeleton was visualized using tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin according to the manufacturer's protocol. The samples were mounted in ProLong Antifade (Molecular Probes Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands) and examined for fluorescein, rhodamine, and Cy3 staining.

RESULTS

Expression of the β1AK756L Mutant in GD25 Cells

Lysine 756 in the transmembrane domain of mouse integrin subunit β1 was mutated to leucine using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), the full-length cDNA was transfected into GD25 cells, and stably expressing clones were established. At least two different clones were used in experiments with comparable results. In Figure 4, two clones designated F4 and A8 are included, otherwise the results obtained with clone A8 are shown. The cell surface expression of β1, and associated α5 and α6 subunits, was verified by flow cytometry (Table 1). The expression of the β1AK756L in GD25 cells resulted in the appearance of α5, and upregulation of α6, on the cell surface as described previously for wild-type β1 (Wennerberg et al., 1996). The mAb 9EG7 recognizes an extracellular conformation-sensitive epitope, whose exposure often, but not always, correlates with active or ligand-bound state of β1 integrins (Lenter et al., 1993; Bazzoni et al., 1998; Wennerberg et al., 1998; Armulik et al., 2000). GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells were incubated with the reference antibody mAb Ha2/5 and with mAb 9EG7 in the absence or in the presence of Mn2+ and analyzed by flow cytometry. The binding of antibodies was similar for both cell lines and was not notably increased after Mn2+ treatment (Table 1). These data show that the K756 mutation in β1 integrin did not alter the exposure of the 9EG7 epitope in integrin extracellular domain.

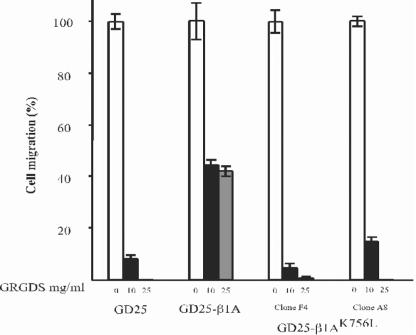

Figure 4.

Cell migration through FN-coated filters in response to serum. The cells were allowed to migrate for 12 h as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Migration of two different clones expressing β1AK756L is shown.

Table 1.

Cell surface expression of integrins on untransfected and transfected GD25 cells

| Cell line/mAb | anti-β1 (Ha2/5) | anti-α5 | anti-α6 | mAb 9EG7 | mAb 9EG7 + Mn2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GD25 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.1 | 3.4 | 4.8 |

| GD25-β1A | 32.8 | 25.0 | 18.1 | 43.3 | 48.3 |

| GD25-β1AK756L | 34.9 | 20.0 | 15.7 | 43.7 | 39.9 |

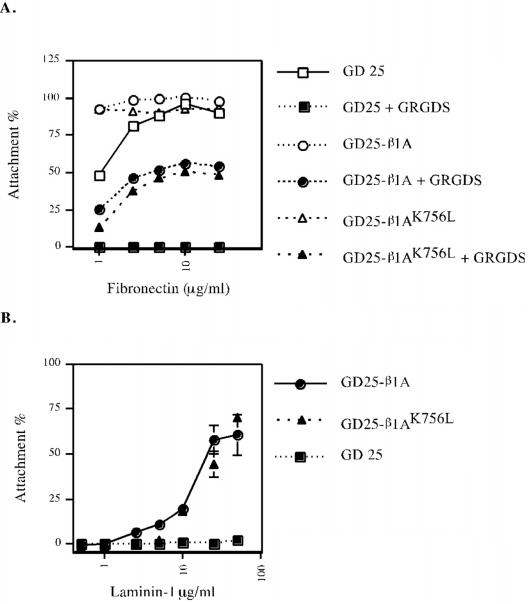

Attachment of GD25-β1AK756L Cells to ECM Proteins

The competence of β1AK756L integrins to mediate cell adhesion to laminin-1 (LN-1) via α6β1 and to FN via α5β1 was tested. When cells were plated on FN, the GRGDS peptide was added to block adhesion via endogenous αvβ3 on GD25 cells (Wennerberg et al., 1998). The GD25-β1AK756L cells attached to LN-1 and to FN as efficiently as GD25 cells expressing wild-type β1 (Figure 2). Thus, the extracellular domain of β1AK756L integrins possesses a conformation that is competent for ligand binding.

Figure 2.

Attachment of GD25, GD25-β1A, and GD25-β1AK756L to FN (A) and LN-1 (B). Cell attachment is expressed as percentage of the number of cells bound to VN. The GRGDS peptide (0.5 mg/ml) was added to block cell attachment to FN via αvβ3.

Spreading and Migration

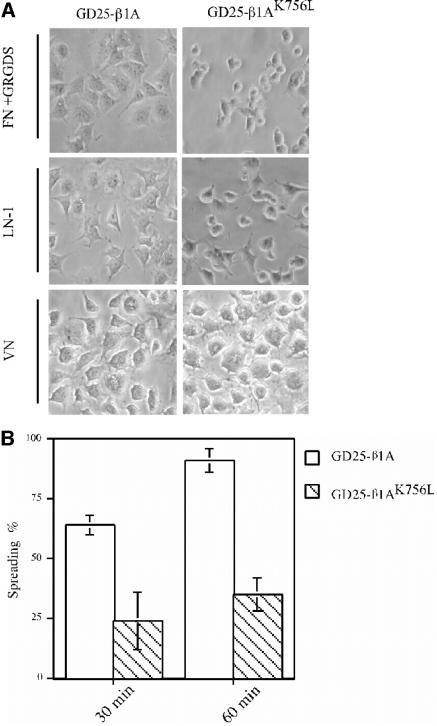

Although the GD25-β1AK756L cells adhered equally well as GD25-β1A cells to LN-1 and FN, they spread poorly (Figure 3A). Almost all GD25-β1A cells had spread within 1 h after plating to LN-1, whereas >50% of GD25-β1AK756L remained unspread (Figure 3B). No obvious differences in morphology were observed between the GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells when cells were spread on vitronectin (VN) via αvβ3 (Figure 3A). However, the GD25-β1AK756L cells plated on LN-1 and FN acquired a rounded shape, whereas the GD25-β1A cells were flattened and exhibited membrane extensions, ruffles, and organized stress fibers, as revealed by staining the actin cytoskeleton (our unpublished data).

Figure 3.

Consequences of the K756 mutation in integrin β1 subunit on cell spreading and morphology. (A) Phase-contrast images of GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells spread on FN in the presence of the GRGDS peptide (0.2 mg/ml), LN-1, and VN for 2 h. (B) Diagram depicting the percentage of spread GD25-β1A (white bars) and GD25-β1AK756L (striped bars) cells on LN-1 (25 μg/ml) (see MATERIALS AND METHODS for details).

To test the capability of β1AK756L to contribute to cell migration, a transfilter migration assay was performed. Migration of the GD25-β1AK756L cells was dramatically reduced and those cells exhibited only a minimal migration on FN when αvβ3 was blocked (Figure 4). Thus, K756 in the β1 subunit is necessary for efficient β1-mediated cell spreading and migration.

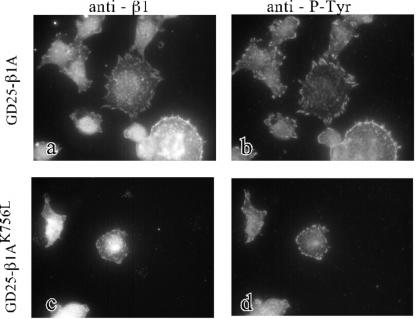

GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells were stained for β1 integrins and focal adhesion proteins after spreading on FN. Both wild-type and K756L β1 integrins colocalized with phosphotyrosine (Figure 5) as well as with paxillin, vinculin, and FAK (our unpublished data). Photographs were taken only from relatively well spread GD25-β1AK756L cells. Notably, the clusters of β1 integrins and focal adhesion proteins at the periphery of GD25-β1AK756L cells were small compared with focal adhesions formed in GD25-β1A cells. The possibility that the mutation K756L could cause ligand-independent localization to focal adhesion was tested. However, no β1AK756L was found at focal contacts when the GD25-β1AK756L cells were plated on VN (our unpublished data).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent detection of colocalization of β1-integrins with phosphotyrosine-containing clusters in GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells. Double stainings for β1 (a and c) and phosphotyrosine (b and d) are shown for GD25-β1A (a and b) and GD25-β1AK756L (c and d) cells. The cells were plated on FN coated (25 μg/ml) chamber slides in the presence of the GRGDS peptide (0.2 mg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, fixed with paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized before incubation with antibodies against β1 and phosphotyrosine.

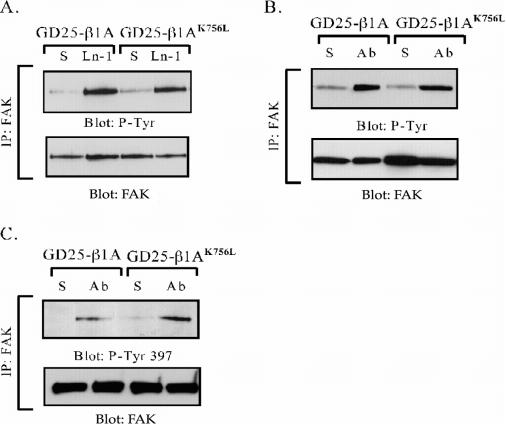

Activation of FAK/Src in GD25-β1AK756L Cells

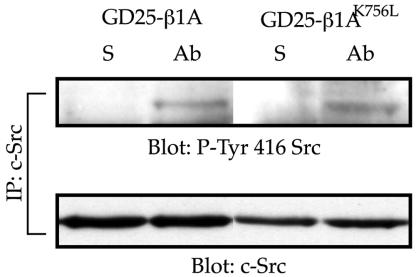

Because the cytosolic protein tyrosine kinase FAK has been implicated in integrin-mediated cell spreading and migration (Ilic et al., 1995), we tested whether FAK was activated in the GD25-β1AK756L cells after β1 clustering. No difference in total tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK was seen between wild-type and mutant cells in response to adhesion to either LN-1 or anti-β1 IgG (Figure 6, A and B) or to FN + GRGDS peptide (our unpublished data) when analyzed with a generic anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Western blot with the site-specific phosphotyrosine-397 and -576 antibodies showed that FAK was phosphorylated at these sites also in the GD25-β1AK756L cells after β1-mediated adhesion (Figures 6C and 9D). According to current models, Tyr-397 is autoor transphosphorylated by FAK as a response to unknown activation signals after integrin ligation (Parsons, 2003). Src can be activated by binding to the pTyr-397 site in FAK as well as by other mechanisms. We found that the phosphorylation of c-Src on the Tyr-416 in the activation loop was not affected by the K756L mutation in the β1-subunit (Figure 7), showing that the activation of FAK and Src was not significantly disturbed in the GD25-β1AK756L cells.

Figure 6.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK in GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells after β1-mediated adhesion. FAK was immunoprecipitated from cells kept in suspension (S), or plated on LN-1 or anti-β1 mAb Ha2/5 (Ab) for 1 h. Immunoprecipitated material was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and the filters were probed for phosphotyrosine (A and B) and for FAK phosphotyrosine-397 by using site-specific antibody (C). After stripping, the filters were reprobed with anti-FAK mAb as a loading control.

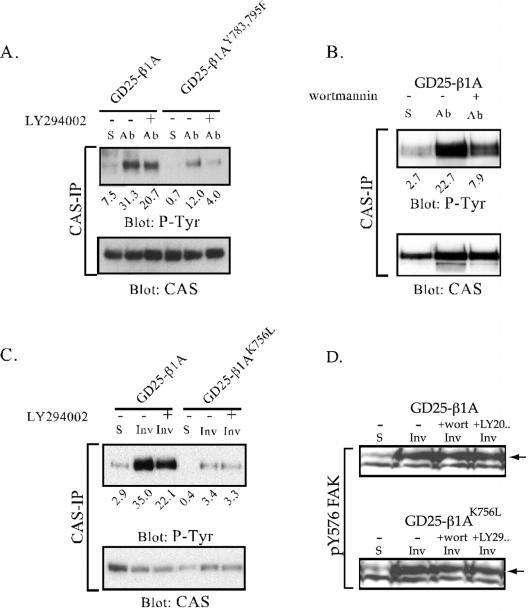

Figure 9.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS and FAK after β1-mediated adhesion in the presence of PI3K inhibitors. CAS was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates prepared from suspended cells (S) or from cells adhering to anti-β1 mAb (Ab) or to invasin (Inv) for 1 h. For the analysis of FAK phosphorylation the cells were lysed directly in SDS sample buffer. Before plating, the cells were treated with LY294002 (20 μM; A and C) or wortmannin (100 nM; B) (+), or with the diluent (dimethyl sulfoxide) as a control (-). Precipitated material was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and sequentially blotted for phosphotyrosine and CAS protein. The relative intensities of the bands versus the gel background are represented by arbitrary units under each lane. In D, equal amounts of cell lysate were blotted for pY576 FAK. Arrows point at bands corresponding to FAK.

Figure 7.

Detection of active c-Src in GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells adhering to anti-β1 mAb. c-Src was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates prepared from suspended cells (S) or from cells adhering to anti-β1 mAb for 1 h. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The membranes were first blotted for pY-416 Src and, after stripping, for total c-Src.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation of CAS

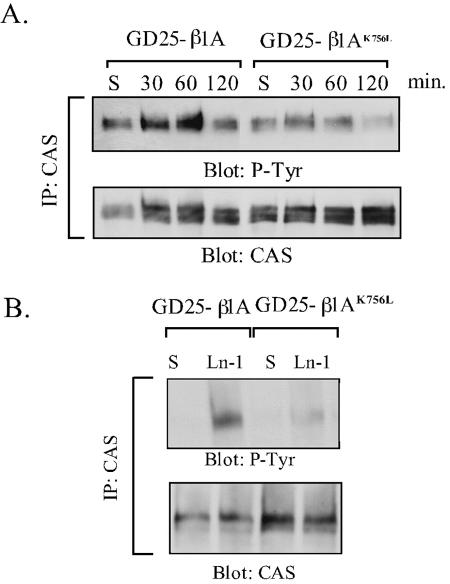

CAS is a docking protein that becomes tyrosine phosphorylated in response to cell adhesion and is required for integrin-mediated cell migration (Burridge et al., 1992; Vuori and Ruoslahti, 1995; Abassi et al., 2003). Because the altered phosphorylation of CAS could cause the observed defects in spreading and migration of the GD25-β1AK756L cells, the phosphorylation state of CAS was examined in immunoprecipitates from GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells. As shown in Figure 8A, a peak of tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS was seen 60 min after plating the cells onto anti-β1 integrin antibody in both cell lines. However, CAS tyrosine phosphorylation was strongly reduced in the mutant cells compared with GD25-β1A cells. In contrast to CAS, tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin, another major docking protein multiply tyrosine phosphorylated upon cell adhesion (Burridge et al., 1992), was not affected by the β1AK756L mutation (our unpublished data). Similar results were obtained when the cells were seeded onto the natural ligands LN-1 (Figure 8B), FN (in the presence of the GRGDS peptide; our unpublished data), or invasin (Figure 9)

Figure 8.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS in GD25-β1A and GD25-β1AK756L cells. CAS was immunoprecipitated from lysates of suspended cells (S), or cells adhering to anti-β1 mAb (A) or LN-1 (B). (A) Time curve of CAS phosphorylation after β1-mediated cell adhesion. (B) Phosphorylation of CAS in cells plated on LN-1 for 1 h. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters, which were blotted for phosphotyrosine (mAb RC-20) and, after stripping, for CAS protein.

Thus, although FAK is activated after β1AK756L-mediated adhesion to levels comparable to those of the wild-type β1A, the phosphorylation of CAS is considerably reduced. These data support the conclusion (Wennerberg et al., 2000; Gustavsson et al., 2002) that both FAK-dependent and -independent signals contribute to tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS after β1-mediated adhesion and identify the lysine in the membrane proximal region of β1 as an essential residue for regulation of the FAK-independent pathway. Furthermore, no difference in tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and CAS was observed whether cells were adhering to the antiintegrin mAb or to natural ligands.

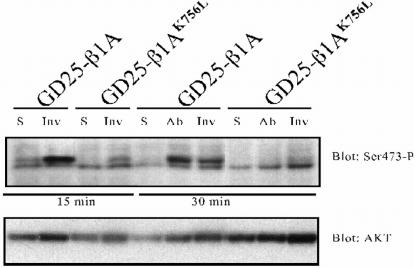

The K756L Mutation in β1A Subunit Affects PI3K-dependent Tyrosine Phosphorylation of CAS

CAS is known to become tyrosine phosphorylated also after growth factor stimulation (e.g., epidermal growth factor), and this event is dependent on PI3K (Ojaniemi et al., 1997). We therefore investigated whether PI3K is involved in any of the two integrin-mediated pathways of CAS phosphorylation. For this analysis, the cell lines GD25-β1AK756L and GD25-β1AYY783,795FF were used, in which the FAK-independent and FAK-dependent pathway, respectively, are blocked (Figure 9; Wennerberg et al., 2000). Before plating cells on dishes coated with anti-β1 mAbs or with GST-invasin, the cells were preincubated with the PI3K inhibitors LY294002 or wortmannin, or left untreated. As shown in Figure 9, a significant reduction was seen in GD25-β1A cells in the presence of either inhibitor in cells seeded both on anti-β1 antibody (Figure 9, A and B) or GST-invasin (Figure 9C). Although LY294002 attenuated tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS in GD25-β1AYY783,795FF cells, it caused little or no effect in GD25-β1AK756L cells (Figure 9). Neither of the inhibitors had any detectable effect on phosphorylation of FAK (Figure 9D) or Src family kinases (our unpublished data). These data suggest that the FAK/Src-independent pathway to CAS tyrosine phosphorylation involves activation of PI3K by the K756-containing part of the β1 subunit.

Thus, the primary effect of the K756L mutation could be on the activation of PI3K or on a tyrosine kinase downstream of PI3K. The former possibility was investigated by monitoring phosphorylation of serine-473 on Akt, a welldocumented PI3K-dependent event. Akt was rapidly phosphorylated at this site in response to adhesion via wild-type β1-integrins to anti-β1 antibodies or to invasin. In contrast, only minimal phosphorylation of serine-473 was induced by β1AK756L integrins (Figure 10). The phosphorylation of Ser-473 on Akt was completely blocked by preincubation of the cells with LY294002 or wortmannin (our unpublished data). We therefore conclude that the mutation affects PI3K activity, which in turn results in reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS.

Figure 10.

Phosphorylation of PKB/Akt on serine-473 after β1-mediated adhesion. Cell lysates were prepared from suspended cells (S) or from cells adhering to anti-β1 mAb (Ab) or to invasin (Inv) for the indicated times. The lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filter, and the filter was blotted with an antibody specific for PKB/Akt phospho-serine-473. After stripping, the filter was blotted for Akt1/2 protein. The lower band occurring in phospho-serine-473 blot is unspecific.

DISCUSSION

Our previous work has shown that lysine 752 in human β1 (756 in mouse) and the corresponding lysine in other integrin α and β chains is buried in the membrane (Armulik et al., 1999). Because this basic residue is conserved in the 18 α and eight β subunits, which represent two separate gene families, it could be important for integrin function. In this study, we show that this indeed is the case. Replacement of the lysine with leucine, which essentially corresponds to removal of an amino group, strongly affected β1 integrin-mediated cell spreading and migration. To make an initial characterization of the defect underlying the mutant integrin phenotype we looked at the activity of signaling proteins involved in cell migration.

Activation of FAK and Src after β1AK756L adhesion occurred normally, as judged by the presence of specific phosphotyrosine residues in FAK and Src. Furthermore, paxillin, the downstream target of the FAK/Src complex, was phosphorylated to an extent similar to that induced by the wild-type integrin. In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS was significantly reduced. Thus, defective CAS phosphorylation may be the cause of, or at least contribute to, the reduced spreading and migration mediated by β1AK756L.

Diminished CAS phosphotyrosine levels in GD25-β1AK756L cells could result from reduced kinase activity or increased tyrosine phosphatase activity. However, the latter alternative seems less likely because incubation of cells with the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor vanadate did not normalize the phosphorylation of CAS in GD25-β1AK756L cells in response to integrin ligation (our unpublished data).

CAS is generally considered to become tyrosine phosphorylated by the FAK/Src complex in response to cell adhesion. This conclusion is supported by the absence of integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS in cells lacking Src-family kinases (Klinghoffer et al., 1999). Nevertheless, several studies have found that tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS did not correlate closely with FAK activity (Jucker et al., 1997; Eisenmann et al., 1999; Kira et al., 2002; Konrad et al., 2003; Kwong et al., 2003) and that other tyrosine kinases, such as Fyn/Yes (Klinghoffer et al., 1999), Abl (Feller et al., 1994; Riggins et al., 2003), and Etk (Abassi et al., 2003) can phosphorylate CAS. Interestingly, tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS in platelets occurs before FAK activation and seems to be dependent on phosphoinositide turnover (Ohmori et al., 2000). PI3K activity was also necessary for epidermal growth factor induced tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS in Rat-1 cells (Ojaniemi et al., 1997). These reports are in line with our data, which indicate that PI3K activity promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS after β1-mediated adhesion.

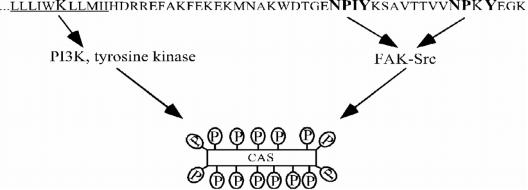

Our previous work with GD25 cells transfected with the β1B splice variant, or the β1A variant with mutated tyrosines in the two NPXY motifs, showed that activation of FAK upon clustering of β1 integrins was attenuated in both cell lines. The β1 integrin-mediated CAS tyrosine phosphorylation still occurred in these cells but was strongly reduced (Wennerberg et al., 2000; Gustavsson et al., 2002). In the present report, we show that mutation of lysine in the transmembrane domain of the β1 subunit caused reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS, although FAK activity was unaffected. By applying PI3K inhibitors, and monitoring the levels of Akt phosphoserine 473 as a readout of PI3K activity, we demonstrated that mutation of K756 affected integrin-mediated activation of PI3K, which in turn was required for full tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS. Figure 11 depicts a summary of these findings and suggests the existence of two pathways leading to tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS: tyrosines in the cytoplasmic NPXY motifs of β1 are required for FAK activation and thereby for tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS by the FAK/Src complex, whereas the lysine in the transmembrane domain is required for PI3K-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS. The identity of the proposed integrin-regulated PI3K-dependent tyrosine kinase is presently not known. Based on the published data and our observations using protein kinase inhibitors, several candidate kinases can be considered, including the Src-family kinases Fyn and Yes (Wary et al., 1998; Klinghoffer et al., 1999), growth factor receptors (Sundberg and Rubin, 1996; Moro et al., 2002), Abl (Feller et al., 1994; Riggins et al., 2003), and the Tec family kinases (Chen et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2001; Abassi et al., 2003).

Figure 11.

Proposed model for β1 integrin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS. The NPXY motifs in the cytoplasmic tail of the β1-subunit are required for activation of FAK/Src, whereas the lysine in the transmembrane domain is involved in the activation of a putative PI3K-dependent tyrosine kinase leading to the tyrosine phosphorylation of CAS.

Tyrosine phosphorylation has been shown to be important for assembly and turnover of focal adhesions and for integrin-mediated signaling (Kornberg et al., 1991; Burridge et al., 1992; Crowley and Horwitz, 1995; Defilippi et al., 1995). FAK is not required for formation of focal adhesions, but it clearly has a key role in dissociating focal adhesions (Ilic et al., 1995; Wennerberg et al., 2000). The cellular phenotype resulting from the K756L mutation in β1 suggests that the affected tyrosine kinase pathway is involved in earlier responses of integrin ligation, which lead to cell spreading and actin reorganization. The conserved lysine is located in the segment of β subunits, often referred to as “membrane proximal,” which has been suggested to regulate transmembrane conformational changes during activation (“inside-out” signaling) of integrin αIIbβ3 (Li et al., 2002; Liddington and Ginsberg, 2002; Vinogradova et al., 2002). However, this process was apparently not affected by the K756L mutation because the mutant integrin maintained ligand binding competence. Thus, in addition to proposing the existence of a new signaling pathway from β1 integrins to PI3K to CAS, the present study demonstrates that 1) the membrane-proximal segment of integrins mediates also outside-in signals, and 2) this mechanism is distinct from that used during integrin activation. Further studies are required to determine the exact role of the membrane proximal basic residue in integrin signaling, for example, its possible participation in integrin oligomerization or association of integrins with other plasma membrane-anchored or cytoplasmic proteins (Li et al., 2001; Stipp et al., 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ivan Dikic (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Uppsala, Sweden) and Dr. Peter Ekblom (Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Lund, Sweden) for support and helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (no. 7147), Swedish Cancer Foundation (no. 4158) and King Gustaf V: 80-års Fond.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0700. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0700.

Abbreviations used: BSA, bovine serum albumin; CAS, Crk-associated substrate; ECM, extracellular matrix; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FN, fibronectin; GST, glutathione S-transferase; LN, laminin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SH, Src homology; VN, vitronectin.

References

- Abassi, Y.A., Rehn, M., Ekman, N., Alitalo, K., and Vuori, K. (2003). p130Cas couples the tyrosine kinase Bmx/Etk with regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35636-35643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik, A., Nilsson, I., von Heijne, G., and Johansson, S. (1999). Determination of the border between the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of human integrin subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37030-37034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik, A., Svineng, G., Wennerberg, K., Fassler, R., and Johansson, S. (2000). Expression of integrin subunit beta1B in integrin beta1-deficient GD25 cells does not interfere with alphaVbeta3 functions. Exp. Cell Res. 254, 55-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakin, A.V., Tomlinson, A.K., Bhowmick, N.A., Moses, H.L., and Arteaga, C.L. (2000). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36803-36810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni, G., Ma, L., Blue, M.L., and Hemler, M.E. (1998). Divalent cations and ligands induce conformational changes that are highly divergent among beta1 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6670-6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottger, B.A., Hedin, U., Johansson, S., and Thyberg, J. (1989). Integrin-type fibronectin receptors of rat arterial smooth muscle cells: isolation, partial characterization and role in cytoskeletal organisation and control of differentiated properties. Differentiation 41, 158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesewitz, R., Kern, A., Smilenov, L.B., David, F.S., and Marcantonio, E.E. (1996). The membrane-cytoplasm interface of integrin alpha subunits is critical for receptor latency. Mol. Biol. Cell 7, 1499-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower, D.L., Brower, S.M., Hayward, D.C., and Ball, E.E. (1997). Molecular evolution of integrins: genes encoding integrin beta subunits from a coral and a sponge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9182-9187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge, K., Turner, C.E., and Romer, L.H. (1992). Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly. J. Cell Biol. 119, 893-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary, L.A., Chang, J.F., and Guan, J.L. (1996). Stimulation of cell migration by overexpression of focal adhesion kinase and its association with Src and Fyn. J. Cell Sci. 109, 1787-1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary, L.A., and Guan, J.L. (1999). Focal adhesion kinase in integrin-mediated signaling. Front. Biosci. 4, D102-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary, L.A., Han, D.C., Polte, T.R., Hanks, S.K., and Guan, J.L. (1998). Identification of p130Cas as a mediator of focal adhesion kinase-promoted cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 140, 211-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R., Kim, O., Li, M., Xiong, X., Guan, J.L., Kung, H.J., Chen, H., Shimizu, Y., and Qiu, Y. (2001). Regulation of the PH-domain-containing tyrosine kinase Etk by focal adhesion kinase through the FERM domain. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 439-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, E., and Horwitz, A.F. (1995). Tyrosine phosphorylation and cytoskeletal tension regulate the release of fibroblast adhesions. J. Cell Biol. 131, 525-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defilippi, P., Retta, S.F., Olivo, C., Palmieri, M., Venturino, M., Silengo, L., and Tarone, G. (1995). p125FAK tyrosine phosphorylation and focal adhesion assembly: studies with phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. Exp. Cell Res. 221, 141-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolfi, F., Garcia-Guzman, M., Ojaniemi, M., Nakamura, H., Matsuda, M., and Vuori, K. (1998). The adaptor protein Crk connects multiple cellular stimuli to the JNK signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15394-15399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide, B.L., Turck, C.W., and Escobedo, J.A. (1995). Identification of Tyr-397 as the primary site of tyrosine phosphorylation and pp60src association in the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 2819-2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, K.M., McCarthy, J.B., Simpson, M.A., Keely, P.J., Guan, J.L., Tachibana, K., Lim, L., Manser, E., Furcht, L.T., and Iida, J. (1999). Melanoma chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan regulates cell spreading through cdc42, ack-1 and p130cas [In Process Citation]. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller, S.M., Knudsen, B., and Hanafusa, H. (1994). c-Abl kinase regulates the protein binding activity of c-Crk. EMBO J. 13, 2341-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti, F.G., and Ruoslahti, E. (1999). Integrin signaling. Science 285, 1028-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, A., Armulik, A., Brakebusch, C., Fassler, R., Johansson, S., and Fallman, M. (2002). Role of the beta1-integrin cytoplasmic tail in mediating invasin-promoted internalization of Yersinia. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2669-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Y., Haimovich, B., Reszka, A., Boettiger, D., and Horwitz, A. (1990). Expression and function of chicken integrin β1 subunit and its cytoplasmic domain mutants in mouse NIH 3T3 cells. J. Cell Biol. 110, 175-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs, M.L., Jakes, S., Stacker, S.A., Wallace, R.W., and Springer, T.A. (1991). The cytoplasmic domain of the integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 β subunit: sites required for binding to intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and the phorbol ester-stimulated phosphorylation site. J. Exp. Med. 174, 1227-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, R.O. (1992). Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 69, 11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, D., et al. (1995). Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature 377, 539-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isberg, R.R., and Leong, J.M. (1990). Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell 60, 861-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, M., McKenna, K., da Silva, A.J., Rudd, C.E., and Feldman, R.A. (1997). The Fes protein-tyrosine kinase phosphorylates a subset of macrophage proteins that are involved in cell adhesion and cell-cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2104-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira, M., Sano, S., Takagi, S., Yoshikawa, K., Takeda, J., and Itami, S. (2002). STAT3 deficiency in keratinocytes leads to compromised cell migration through hyperphosphorylation of p130(cas). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12931-12936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa, E., Hashimoto, Y., Kobayashi, S., Sugimura, H., Kurata, T., and Matsuda, M. (1998a). Activation of Rac1 by a Crk SH3-binding protein, DOCK180. Genes Dev. 12, 3331-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokawa, E., Hashimoto, Y., Kurata, T., Sugimura, H., and Matsuda, M. (1998b). Evidence that DOCK180 up-regulates signals from the CrkII-p130(Cas) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 24479-24484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemke, R.L., Leng, J., Molander, R., Brooks, P.C., Vuori, K., and Cheresh, D.A. (1998). CAS/Crk coupling serves as a “molecular switch” for induction of cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 140, 961-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinghoffer, R.A., Sachsenmaier, C., Cooper, J.A., and Soriano, P. (1999). Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. EMBO J. 18, 2459-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klint, P., Kanda, S., and Claesson-Welsh, L. (1995). Shc and a novel 89-kDa component couple to the Grb2-Sos complex in fibroblast growth factor-2-stimulated cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 23337-23344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad, R.J., Gold, G., Lee, T.N., Workman, R., Broderick, C.L., and Knierman, M.D. (2003). Glucose stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrate in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28116-28122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg, L.J., Earp, H.S., Turner, C.E., Prockop, C., and Juliano, R.L. (1991). Signal transduction by integrins: increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation caused by clustering of beta 1 integrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 8392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, L., Wozniak, M.A., Collins, A.S., Wilson, S.D., and Keely, P.J. (2003). R-Ras promotes focal adhesion formation through focal adhesion kinase and p130(Cas) by a novel mechanism that differs from integrins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 933-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFlamme, S.E., Thomas, L.A., Yamada, S.S., and Yamada, K.M. (1994). Single subunit chimeric integrins as mimics and inhibitors of endogenous integrin functions in receptor localization, cell spreading and migration, and matrix assembly. J. Cell Biol. 126, 1287-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenter, M., Uhlig, H., Hamann, A., Jeno, P., Imhof, B., and Vestweber, D. (1993). A monoclonal antibody against an activation epitope on mouse integrin chain β1 blocks adhesion of lymphocytes to the endothelial integrin α6β1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9051-9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong, L., Hughes, P.E., Schwartz, M.A., Ginsberg, M.H., and Shattil, S.J. (1995). Integrin signaling: roles for the cytoplasmic tails of αIIbβ3 in the tyrosine phosphorylation of pp125FAK. J. Cell Sci. 108, 3817-3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.M., Baskaran, R., Taagepera, S., Schwartz, M.A., and Wang, J.Y. (1996). Integrin regulation of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity and cytoplasmic-nuclear transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 15174-15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Babu, C.R., Lear, J.D., Wand, A.J., Bennett, J.S., and DeGrado, W.F. (2001). Oligomerization of the integrin alphaIIbbeta 3, roles of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12462-12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Babu, C.R., Valentine, K., Lear, J.D., Wand, A.J., Bennett, J.S., and DeGrado, W.F. (2002). Characterization of the monomeric form of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the integrin beta 3 subunit by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 41, 15618-15624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., Mitra, N., Gratkowski, H., Vilaire, G., Litvinov, R., Nagasami, C., Weisel, J.W., Lear, J.D., DeGrado, W.F., and Bennett, J.S. (2003). Activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 by modulation of transmembrane helix associations. Science 300, 795-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddington, R.C., and Ginsberg, M.H. (2002). Integrin activation takes shape. J. Cell Biol. 158, 833-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, S., Akiyama, S.K., and Yamada, K.M. (1995a). Synergistic roles for receptor occupancy and aggregation in integrin transmembrane function. Science 267, 883-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, S., Teramoto, H., Coso, O.A., Gutkind, J.S., Burbelo, P.D., Akiyama, S.K., and Yamada, K.M. (1995b). Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J. Cell Biol. 131, 791-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro, L., et al. (2002). Integrin-induced epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor activation requires c-Src and p130Cas and leads to phosphorylation of specific EGF receptor tyrosines. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9405-9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, T.E., Katagiri, Y., Faull, R.J., Peter, K., Tamura, R., Quaranta, V., Loftus, J.C., Shattil, S.J., and Ginsberg, M.H. (1994). Integrin cytoplasmic domains mediate inside-out signal transduction. J. Cell Biol. 124, 1047-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obergfell, A., Eto, K., Mocsai, A., Buensuceso, C., Moores, S.L., Brugge, J.S., Lowell, C.A., and Shattil, S.J. (2002). Coordinate interactions of Csk, Src, and Syk kinases with [alpha]IIb[beta]3 initiate integrin signaling to the cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 157, 265-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori, T., Yatomi, Y., Inoue, K., Satoh, K., and Ozaki, Y. (2000). Tyrosine dephosphorylation, but not phosphorylation, of p130Cas is dependent on integrin alpha IIb beta 3-mediated aggregation in platelets: implication of p130Cas involvement in pathways unrelated to cytoskeletal reorganization. Biochemistry 39, 5797-5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojaniemi, M., Martin, S.S., Dolfi, F., Olefsky, J.M., and Vuori, K. (1997). The proto-oncogene product p120(cbl) links c-Src and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase to the integrin signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3780-3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J.T. (2003). Focal adhesion kinase: the first ten years. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1409-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiske, H.R., Kao, S.C., Cary, L.A., Guan, J.L., Lai, J.F., and Chen, H.C. (1999). Requirement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in focal adhesion kinase-promoted cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12361-12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, A., Malik, R.K., Hildebrand, J.D., and Parsons, J.T. (1997). Inhibition of cell spreading by expression of the C-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is rescued by coexpression of Src or catalytically inactive FAK: a role for paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6906-6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggins, R.B., DeBerry, R.M., Toosarvandani, M.D., and Bouton, A.H. (2003). Src-dependent association of Cas and p85 phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase in v-Crk-transformed cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 1, 428-437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer, D.D., and Hunter, T. (1996). Evidence for in vivo phosphorylation of the Grb2 SH2-domain binding site on focal adhesion kinase by Src-family protein-tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 5623-5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilenov, L., Forsberg, E., Zeligman, I., Sparrman, M., and Johansson, S. (1992). Separation of fibronectin from a plasma gelatinase using immobilized metal affinity chromatography. FEBS Lett. 302, 227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.I., Islam, T.C., Mattsson, P.T., Mohamed, A.J., Nore, B.F., and Vihinen, M. (2001). The Tec family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases: mammalian Btk, Bmx, Itk, Tec, Txk and homologs in other species. Bioessays 23, 436-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipp, C.S., Kolesnikova, T.V., and Hemler, M.E. (2003). Functional domains in tetraspanin proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, C., and Rubin, K. (1996). Stimulation of β1 integrins on fibroblasts induces PDGF independent tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGF beta-receptors. J. Cell Biol. 132, 741-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svineng, G., and Johansson, S. (1999). Integrin subunits (beta)1C-1 and (beta)1C-2 expressed in GD25T cells are retained and degraded intracellularly rather than localised to the cell surface. J. Cell Sci. 112, 4751-4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana, K., Urano, T., Fujita, H., Ohashi, Y., Kamiguchi, K., Iwata, S., Hirai, H., and Morimoto, C. (1997). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrates by focal adhesion kinase. A putative mechanism for the integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 29083-29090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, J., Erickson, H.P., and Springer, T.A. (2001). C-terminal opening mimics `inside-out' activation of integrin alpha5beta1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 412-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, J., Petre, B.M., Walz, T., and Springer, T.A. (2002). Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell 110, 599-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, O., Velyvis, A., Velyviene, A., Hu, B., Haas, T., Plow, E., and Qin, J. (2002). A structural mechanism of integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) “inside-out” activation as regulated by its cytoplasmic face. Cell 110, 587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuori, K., Hirai, H., Aizawa, S., and Ruoslahti, E. (1996). Introduction of p130cas signaling complex formation upon integrin-mediated cell adhesion: a role for Src family kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2606-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuori, K., and Ruoslahti, E. (1995). Tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and cortactin accompanies integrin-mediated cell adhesion to extracellular matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22259-22262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wary, K.K., Mariotti, A., Zurzolo, C., and Giancotti, F.G. (1998). A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell 94, 625-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg, K., Armulik, A., Sakai, T., Karlsson, M., Fassler, R., Schaefer, E.M., Mosher, D.F., and Johansson, S. (2000). The cytoplasmic tyrosines of integrin subunit beta1 are involved in focal adhesion kinase activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5758-5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg, K., Fässler, R., Wärmegård, B., and Johansson, S. (1998). Mutational analysis of the potential phosphorylation sites in the cytoplasmic domain of integrin β1A. Requirement for threonines 788–789 in receptor activation. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1117-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg, K., Lohikangas, L., Gullberg, D., Pfaff, M., Johansson, S., and Fässler, R. (1996). β1 integrin-dependent and -independent polymerization of fibronectin. J. Cell Biol. 132, 227-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.R., and Berton, G. (1998). Antibody-induced engagement of beta2 integrins in human neutrophils causes a rapid redistribution of cytoskeletal proteins, Src-family tyrosine kinases, and p72syk that precedes de novo actin polymerization. J. Leukoc. Biol. 64, 401-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., Lin, Q., Guan, J.L., and Cerione, R.A. (1999). Activation of the Cdc42-associated tyrosine kinase-2 (ACK-2) by cell adhesion via integrin beta1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8524-8530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatohgo, T., Izumi, M., Kashiwagi, H., and Hayashi, M. (1988). Novel purification of vitronectin from human plasma by heparin affinity chromatography. Cell Struct. Funct. 13, 281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]