Abstract

The use of conventional modalities for chronic neck pain remains debatable, primarily because most treatments have had limited success. We conducted a review of the literature published up to December 2013 on the diagnostic and treatment modalities of disorders related to chronic neck pain and concluded that, despite providing temporary relief of symptoms, these treatments do not address the specific problems of healing and are not likely to offer long-term cures. The objectives of this narrative review are to provide an overview of chronic neck pain as it relates to cervical instability, to describe the anatomical features of the cervical spine and the impact of capsular ligament laxity, to discuss the disorders causing chronic neck pain and their current treatments, and lastly, to present prolotherapy as a viable treatment option that heals injured ligaments, restores stability to the spine, and resolves chronic neck pain.

The capsular ligaments are the main stabilizing structures of the facet joints in the cervical spine and have been implicated as a major source of chronic neck pain. Chronic neck pain often reflects a state of instability in the cervical spine and is a symptom common to a number of conditions described herein, including disc herniation, cervical spondylosis, whiplash injury and whiplash associated disorder, postconcussion syndrome, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and Barré-Liéou syndrome.

When the capsular ligaments are injured, they become elongated and exhibit laxity, which causes excessive movement of the cervical vertebrae. In the upper cervical spine (C0-C2), this can cause a number of other symptoms including, but not limited to, nerve irritation and vertebrobasilar insufficiency with associated vertigo, tinnitus, dizziness, facial pain, arm pain, and migraine headaches. In the lower cervical spine (C3-C7), this can cause muscle spasms, crepitation, and/or paresthesia in addition to chronic neck pain. In either case, the presence of excessive motion between two adjacent cervical vertebrae and these associated symptoms is described as cervical instability.

Therefore, we propose that in many cases of chronic neck pain, the cause may be underlying joint instability due to capsular ligament laxity. Currently, curative treatment options for this type of cervical instability are inconclusive and inadequate. Based on clinical studies and experience with patients who have visited our chronic pain clinic with complaints of chronic neck pain, we contend that prolotherapy offers a potentially curative treatment option for chronic neck pain related to capsular ligament laxity and underlying cervical instability.

Keywords: Atlanto-axial joint, Barré- Liéou syndrome, C1-C2 facet joint, capsular ligament laxity, cervical instability, cervical radiculopathy, chronic neck pain, facet joints, post-concussion syndrome, prolotherapy, spondylosis, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, whiplash.

INTRODUCTION

In the realm of pain management, an ever-growing number of treatment-resistant patients are being left with relatively few conventional treatment options that effectively and permanently relieve their chronic pain symptoms. Chronic cervical spine pain is particularly challenging to treat, and data regarding the long-term efficacy of traditional therapies has been extremely discouraging [1]. The prevalence of neck pain in the general population has been reported to range between 30% and 50%, with women over 50 making up the larger portion [1-3]. Although many of these cases resolve with time and require minimal intervention, the recurrence rate of neck pain is high, and about one-third of people will suffer from chronic neck pain (defined as pain that persists longer than 6 months), and 5% will develop significant disability and reduction in quality of life [2, 4]. For this group of chronic pain patients, modern medicine offers few options for long-term recovery.

Treatment protocols for acute and sub-acute neck pain are standard and widely agreed upon [1, 2]. However, conventional treatments for chronic neck pain remain debatable and include interventions such as use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotics for pain management, cervical collars, rest, physiotherapy, manual therapy, strengthening exercises, and nerve blocks. Furthermore, the literature on long-term treatment outcomes has been inconclusive at best [5-9]. Chronic neck pain due to whiplash injury or whiplash associated disorder (WAD) is particularly resistant to long-term treatment; conventional treatment for these conditions may give temporary relief but long-term outcomes have been disappointing [10].

In light of the poor treatment options and outcomes for chronic neck pain, we propose that in many of these cases, the underlying condition may be related to capsular ligament laxity and subsequent joint instability of the cervical spine. Should this be the case and joint instability is the fundamental problem causing chronic neck pain, a new treatment approach may be warranted.

The diagnosis of chronic neck pain due to cervical instability is particularly challenging. In most cases, diagnostic tools for detecting cervical instability have been inconsistent and lack specificity [11-15], and are therefore inadequate. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of cervical instability may better enable practitioners to recognize and treat the condition more effectively. For instance, when cervical instability is related to injury of soft tissue (eg, ligaments) alone and not fracture, the treatment modality should be one that stimulates the involved soft tissue to regenerate and repair itself.

In that context, comprehensive dextrose prolotherapy offers a promising treatment option for resolving cervical instability and the subsequent pain and disability it causes. The distinct anatomy of the cervical spine and the pathology of cervical instability described herein underlie the rationale for treating the condition with prolotherapy.

ANATOMY

The cervical spine consists of the first seven vertebrae in the spinal column and is divided into two segments, the upper cervical (C0-C2) and lower cervical (C3-C7) regions. Despite having the smallest vertebral bodies, the cervical spine is the most mobile segment of the entire spine and must support a high degree of movement. Consequently, it is highly reliant on ligamentous tissue for stabilizing the neck and spinal column, as well as for controlling normal joint motion; as a result, the cervical spine is highly susceptible to injury.

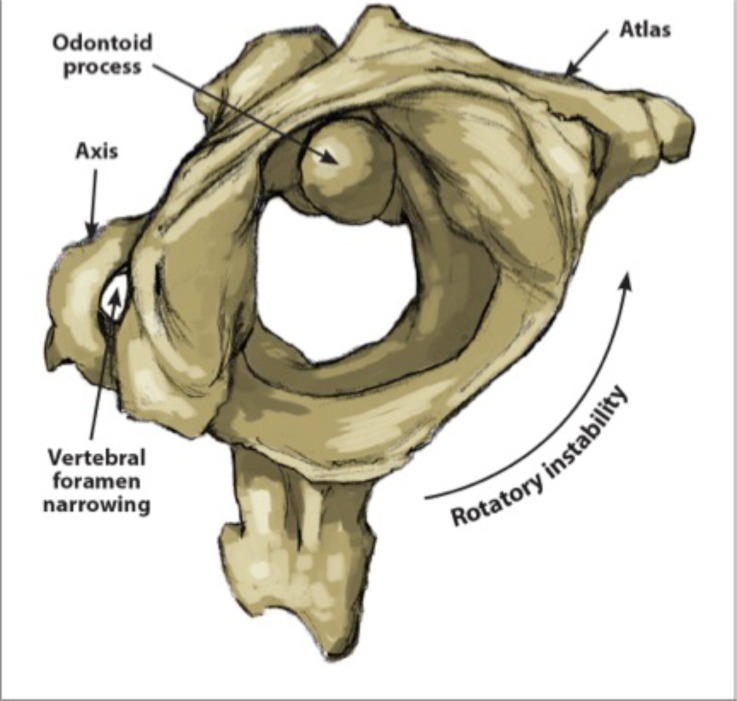

The upper cervical spine consists of C0, called the occiput, and the first two cervical vertebrae, C1 and C2, or atlas and axis, respectively. C1 and C2 are more specialized than the rest of the cervical vertebrae. C1 is ring-shaped and lacks a vertebral body. C2 has a prominent vertebral body called the odontoid process or dens which acts as a pivot point for the C1 ring [16]. This pivoting motion (Fig. 1), coupled with the lack of intervertebral discs in the upper cervical spine, allows for more movement and rotation of the joint, thus facilitating mobility rather than stability [17]. Collectively, the upper cervical spine is responsible for 50% of total neck flexion and extension at the atlanto-occipital (C0-C1) joint, as well as 50% of total neck rotation that occurs at the atlanto-axial joint (C1-C2) [16]. This motion is possible because the atlas (C1) rotates around the axis (C2) via the dens and the anterior arch of the atlas.

Fig. (1).

Atlanto-axial rotational instability. The atlas is shown in the rotated position on the axis. The pivot is the eccentrically placed odontoid process. In rotation, the wall of the vertebral foramen of Cl decreases the opening of the spinal canal between Cl and C2. This can potentially cause migraine headaches, C2 nerve root impingement, dizziness, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, 'drop attacks; neck-tongue syndrome, Barré-Liéou syndrome, severe neck pain, and tinnitus.

The intrinsic, passive stability of the spine is provided by the intervertebral discs and surrounding ligamentous structures. The upper cervical spine is stabilized solely by ligaments, including the transverse, alar, and capsular ligaments. The transverse ligament runs behind the dens, originating on a small tubercle on the medial side of a lateral mass of the atlas and inserting onto the identical tubercle on the other side. Thus, the transverse ligament restricts flexion of the head and anterior displacement of the atlas. The left and right alar ligaments originate from the posterior dens and attach to the medial occipital condyles on the ipsilateral sides. They work to limit axial rotation and are under the greatest tension in rotation and flexion. By holding C1 and C2 in proper position, the transverse and alar ligaments help to protect the spinal cord, brain stem, and nervous system from excess movement in the upper cervical spine [18].

The lower cervical spine, while less specialized, allows for the remaining 50% of neck flexion, extension, and rotation. Each vertebra in this region (C3-C7) has a vertebral body, in between which lies an intervertebral disc, the largest avascular structure of the body. This disc is a piece of fibrocartilage that helps cushion the joints and allows for more stability and is comprised of an inner gelatinous nucleus pulposus, which is surrounded by an outer, fibrous annulus fibrosus. The nucleus pulposus is designed to sustain compression loads and the annulus fibrosus, to resist tension, shear and torsion [19]. The annulus fibrosus is thought to determine the proper functioning of the entire intervertebral disc [20] and has been described as a lamellar structure consisting of 15-26 distinct concentric fibrocartilage layers that constitute a criss-crossing fiber matrix [19]. However, the form of this structure has been disputed. A microdissection study using cadavers reported that the cervical annulus fibrosus does not consist of concentric laminae of collagen fibers as it does in lumbar discs. Instead, the authors contend that the three-dimensional architecture of the cervical annulus fibrosus is more like that of a crescentic anterior interosseous ligament surrounding the nucleus pulposus [21].

In addition to the discs, multiple ligaments and the two synovial joints on each pair of adjacent vertebrae (facet joints) allow for controlled, fully three dimensional motions. Capsular ligaments wrap around each facet joint, which help to maintain stability during neck rotation. Each vertebra in the lower cervical spine (in addition to C2) contains a spinous process that serves as an attachment site for the interspinal ligaments. These tissues connect adjacent spinous processes and limit flexion of the cervical spine. Anteriorly, they meet with the ligamentum flavum.

Three other ligaments, the ligamentum flavum, anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), and posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), help to stabilize the cervical spine during motion and protect against excess flexion and extension of the cervical vertebrae. From C1-C2 to the sacrum, the ligamentum flava run down the posterior aspect of the spinal canal and join the laminae of adjacent vertebrae while helping to maintain proper neck posture. The ALL and PLL both run alongside the vertebral bodies. The ALL begins at the occiput and runs anteriorly to the anterior sacrum, helping to stabilize the vertebrae and intervertebral discs and limit spinal extension. The PLL also helps to stabilize the vertebrae and intervertebral discs, as well as limit spinal flexion. It extends from the body of the axis to the posterior sacrum and runs within the anterior aspect of the spinal canal across from the ligamentum flava.

A spinous process and two transverse processes emanate off the neural arch (or vertebral arch) which lies at the posterior aspect of the cervical vertebral column. The transverse processes are bony prominences that protrude postero-laterally and serve as attachment sites for various muscles and ligaments. With the exception of C7, each of these processes has a foramen which allows for passage of the vertebral artery towards the brain; the C7 transverse process has foramina which allow for passage of the vertebral vein and sympathetic nerves [22]. The transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae are connected via the intertransverse ligaments; each attaches a transverse process to the one below and helps to limit lateral flexion of the cervical spine.

Facet Joints

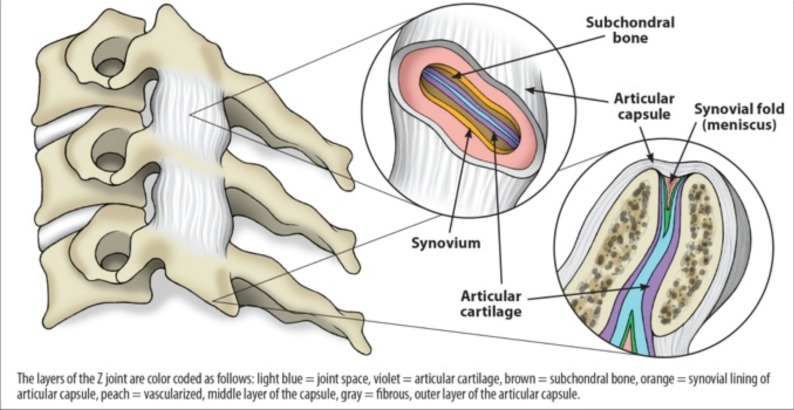

The inferior articular process of the superior cervical vertebra, except for C0-C1, and the superior articular process of the inferior cervical vertebra join to form the facet joints of the cervical spine; in the case of C0-C1, the inferior articular process of C1 joins the occipital condyles. Also referred to as zygapophyseal joints (Fig. 2), the facet joints are diarrthrodial, meaning they function similar to the knee joint in that they contain synovial cells and joint fluid and are surrounded by a capsule. They also contain a meniscus which helps to further cushion the joint, and like the knee, are lined by articular cartilage and surrounded by capsular ligaments, which stabilize the joint. These capsular ligaments hold adjacent vertebrae to one another, and the articular cartilage therein is aligned such that its opposing tissue surfaces provide for a low-friction environment [23].

Fig. (2).

Typical Z (zygapophyseal/ facet) joint. Each facet joint has articular cartilage, the synovium where synovial fluid is produced, and a meniscus.

There is some dissimilarity in facet joint anatomy between the upper and lower cervical spine. Even in the upper cervical region, C0-C1 and C1-C2 facet joints differ anatomically. At C0-C1, the convex shape of the occipital condyles enables them to fit into the concave surface of the inferior articular process. The C1-C2 facet joints are oriented cranio-caudally, meaning they run more parallel to their transverse processes. As such, their capsular ligaments are normally relatively lax, and thus, are inherently less stable and meant to facilitate mobility (i.e., rotation) [23, 24].

In contrast, the facet joints of the lower cervical spine are positioned at more of an angle. In the transverse plane, the angles of the right and left C2-C3 facet joints are estimated to be 32º to 65º and 32º to 60º, respectively, while those of the C6-C7 facet joints are typically steeper at 45º to 75º and 50º to 78º [25]. As the cervical spine extends downward, the angle of the facet joint becomes bigger such that the joint slopes backwards and downwards. Thus, the facet joints of the lower cervical spine have progressively less rotation than those of the upper cervical spine. Furthermore, the presence of intervertebral discs helps give the lower cervical spine more stability.

Nevertheless, injury to any of the facet joints can cause instability to the cervical spine. Researchers have found there is a continuum between the amount of trauma and degree of instability to the cervical facets, with greater trauma causing a higher degree of facet instability [26-28].

CERVICAL CAPSULAR LIGAMENTS

The capsular ligaments are extremely strong and serve as the main stabilizing tissue in the spinal column. They lie close to the intervertebral centers of rotation and provide significant stability in the neck, especially during axial rotation [29]; consequently, they serve as essential components for ensuring neck stability with movement. The capsular ligaments have a high peak force and elongation potential, meaning they can withstand large forces before rupturing. This was demonstrated in a dynamic mechanical study in which the capsular ligaments and ligamentum flavum were shown to have the highest average peak force, up to 220 N and 244 N, respectively [30]. This was reported as considerably greater than the force shown in the anterior longitudinal ligament and middle third disc.

While much has been reported about the strength of the capsular ligaments as related to cervical stability, when damaged, these ligaments lose their strength and are unable to support the cervical spine properly. For instance, in an animal study, it was shown that sequential removal of sheep capsular ligaments and cervical facets caused an undue increase in range of motion, especially in axial rotation, flexion and extension with caudal progression [31]. Human cadaver studies have also indicated that transection or injury of joint capsular ligaments significantly increases axial rotation and lateral flexion [32, 33]. Specifically, the largest increase in axial rotation with damage to a unilateral facet joint was 294% [33].

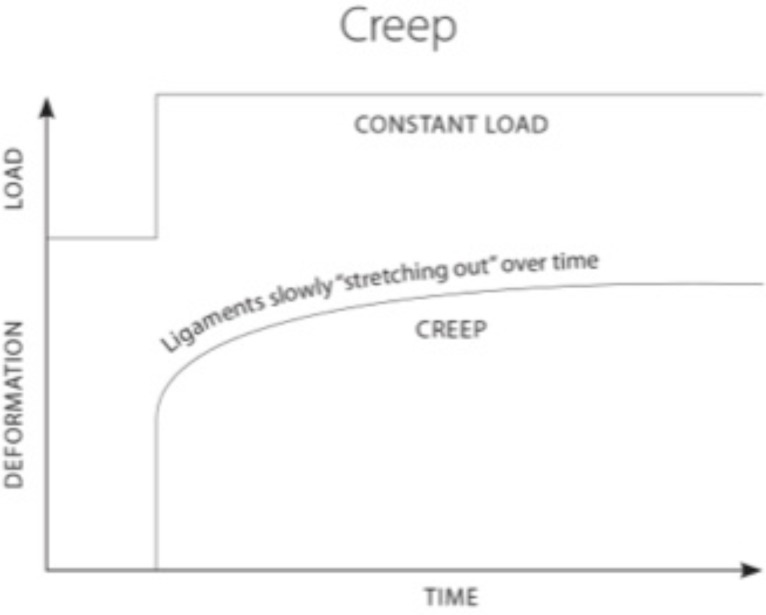

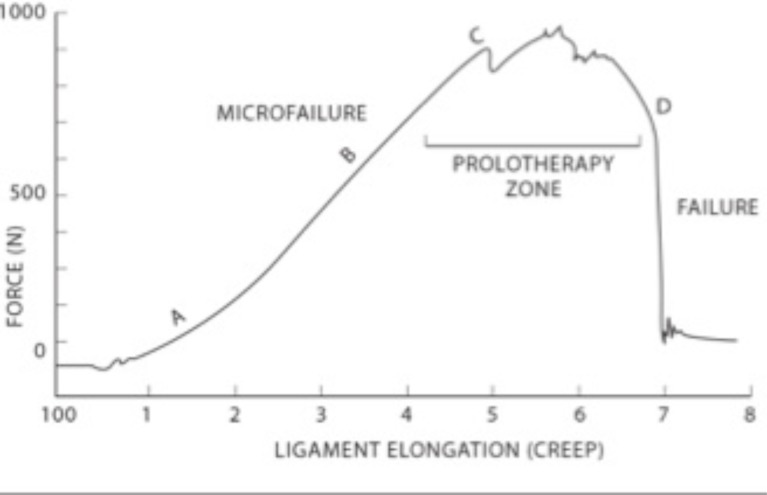

Capsular ligament laxity can occur instantaneously as a single macrotrauma, such as a whiplash injury, or can develop slowly as cumulative microtraumas, such as those from repetitive forward or bent head postures. In either case, the cause of injury occurs through similar mechanisms, leading to capsular ligament laxity and excess motion of the facet joints, which often results in cervical instability. When ligament laxity develops over time, it is defined as “creep” (Fig. 3) and refers to the elongation of a ligament under a constant or repetitive stress [34]. While this constitutes low-level subfailure ligament injuries, it may represent the vast majority of cervical instability cases and can potentially incapacitate people due to disabling pain, vertigo, tinnitus or other concomitant symptoms of cervical instability. Such symptoms can be caused by elongation-induced strains of the capsular ligaments; these strains can progress to subsequent subfailure tears in the ligament fibers or to laxity in the capsular ligaments, leading to instability at the level of the cervical facet joints [35]. This is most evident when the neck is rotated (ie, looking to the left or right) and that movement

Fig. (3).

Ligament laxity and creep. When ligaments are under a constant stress, they display creep behavior. Creep refers to a time-dependent increase in strain and causes ligaments to "stretch out" over time.

causes a “cracking” or “popping” sound. Clinical instability indicates that the spine is unable to maintain normal motion and function between vertebrae under normal physiological loads, inducing irritation to nerves, possible structural deformation, and/or incapacitating pain.

Furthermore, the capsular ligaments surrounding the facet joints are highly innervated by mechanoreceptive and nociceptive free nerve endings. Hence, the facet joint has long been considered the primary source of chronic spinal pain [36-38]. Additionally, injury to these nerves has been shown to affect the overall joint function of the facet joints [39]. Therefore, injury to the capsular ligaments and subsequent nerve endings could explain the prevalence of chronic pain and joint instability in the facet joints of the cervical spine.

CERVICAL INSTABILITY

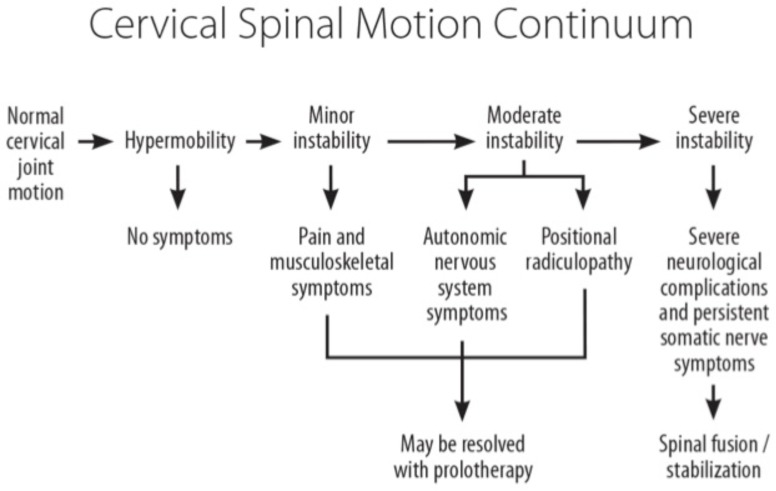

Clinical instability is not to be confused with hypermobility. In general, instability implies a pathological condition with resultant symptoms, whereas joint hypermobility alone does not (Fig. 4). Clinical instability refers to a loss of motion stiffness in a particular spinal segment when the application of force to it produces greater displacement(s) than would otherwise be seen in a normal structure. In clinical instability, symptoms such as pain and muscle spasms can thus be experienced within a person’s range of motion, not just at its furthest extension point. These muscle spasms can cause intense pain and are the body’s response to cervical instability in that the ligaments act as sensory organs involved in ligamento-muscular reflexes. The ligamento-muscular reflex is a protective reflex emanating from mechanoreceptors (ie, pacinian corpuscles, golgi tendon organs, and ruffini endings) in the ligaments and transmitted to the muscles. Subsequent activation of these muscles helps to preserve joint stability, either directly by muscles crossing the joint or indirectly by muscles that do not cross the joint but limit joint motion [40].

Fig. (4).

Cervical spinal motion continuum and role of prolotherapy. When minor or moderate spinal instability occurs, treatment with prolotherapy may be of benefit in alleviating symptoms and restoring normal cervical joint function.

In a clinically unstable joint where neurologic insult is present, it is presumed that the joint has undergone more severe damage in its stabilizing structures, which may include the vertebrae themselves. In contrast, joints that are hypermobile demonstrate increased segmental mobility but are able to maintain their stability and function normally under physiological loads [41].

Clinical instability can be classified as mild, moderate or severe, with the later being associated with catastrophic injury. Minor injuries of the cervical spine are those involving soft tissues alone without evidence of fracture and are the most common causes of cervical instability. Mild or moderate clinical instability is that which is without neurologic (somatic) injury and is typically due to cumulative micro-traumas.

DIAGNOSIS OF CERVICAL INSTABILITY

Cervical instability is a diagnosis based primarily on a patient’s history (ie, symptoms) and physical examination because there is yet to be standardized functional X-rays or imaging able to diagnose cervical instability or detect ruptured ligamentous tissue without the presence of bony lesions [24]. For example, in one autopsy study of cryosection samples of the cervical spine, [42] only one out of ten gross ligamentous disruptions was evident on x-ray. Furthermore, there is often little correlation between the degree of instability or hypermobility shown on radiographic studies and clinical symptoms [43-45]. Even after severe whiplash injuries, plain radiographs are usually normal despite clinical findings indicating the presence of soft tissue damage.

However, functional computerized tomography (fCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans and digital motion x-ray (DMX) are able to adequately depict cervical instability pathology [46, 47]. Studies using fCT for diagnosing soft tissue ligament or post-whiplash injuries have demonstrated the ability of this technique to show excess atlanto-occipital or atlanto-axial movement during axial rotation [48, 49]. This is especially pertinent when patients have signs and symptoms of cervical instability, yet have normal MRIs in a neutral position.

Functional imaging technology, as opposed to static standard films, is necessary for adequate radiologic depiction of instability in the cervical spine because they provide dynamic imaging of the neck during movement and are helpful for evaluating the presence and degree of cervical instability (Fig. 5). There are also specialized physical examination tests specific for upper cervical instability, such as the Sharp-Purser test, upper cervical flexion test, and cervical flexion-rotation test.

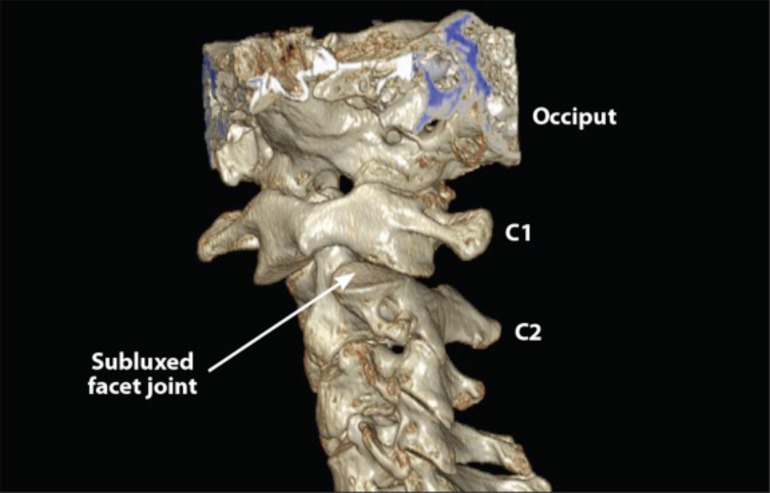

Fig. (5).

3D CT scan of upper cervical spine. C1-C2 instability can easily be seen in the patient, as 70% of C1 articular facet is subluxed posteriorly (arrow) on C2 facet when the patient rotates his head (turns head to the left then the right).

UPPER CERVICAL PATHOLOGY AND INSTABILITY

Although not usually apparent radiographically, injury to the ligaments and soft tissues of C0-C2 from head or neck trauma is more likely than are cervical fractures or subluxation of bones [50, 51]. Ligament laxity across the C0-C1-C2 complex is primarily caused by rotational movements, especially those involving lateral bending and axial rotation [52-54]. With severe neck traumas, especially those with rotation, up to 25% of total lesions can be attributed to ligament injuries of C0-C2 alone. Although some ligament injuries in the C0-C2 region can cause severe neurological impairment, the majority involve sub-failure loads to the facet joints and capsular ligaments, which are the primary source of most chronic pain in post-neck trauma [26, 55].

Due to its lack of osseous stability, the upper cervical spine is also vulnerable to injury by high velocity manipulation. The capsular ligaments of the atlanto-axial joint are especially susceptible to injury from rotational thrusts, and thus, may be at risk during mechanically mediated manipulation. The capsular ligaments in the occipto-atlantal joint function as joint stabilizers and can also become injured due to excessive or abnormal forces [46].

Excessive tension on the capsular ligaments can cause upper cervical instability and related neck pain [56]. Capsular ligament tension is increased during abnormal postures, causing elongation of the capsular ligaments, with magnitudes increased by up to 70% of normal [57]. Such excessive ligament elongation induces laxity to the facet joints, which puts the cervical spine more at risk for further degenerative changes and instability. Therefore, capsular ligament injury appears to cause upper cervical instability because of laxity in the stabilizing structure of the facet joints [58].

CERVICAL PAIN VERSUS CERVICAL RADICULOPATHY

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), cervical spinal pain is pain perceived as anywhere in the posterior region of the cervical spine, defining it further as pain that is “perceived as arising from anywhere within the region bounded superiorly by the superior nuchal line, inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the tip of the first thoracic spinous process, and laterally by sagittal planes tangential to the lateral borders of the neck” [59]. Similarly, cervical pain is divided equally by an imaginary transverse plane into upper cervical pain and lower cervical pain. Suboccipital pain is that pain located between superior nuchal line and an imaginary transverse line through the tip of the second cervical spinous process. Likewise, cervico-occipital pain is perceived as arising in the cervical region and extending over the occipital region of the skull. These sources of pain could be a result of underlying cervical instability.

The IASP defines radicular pain as that arising in a limb or the trunk wall, caused either by ectopic activation of nociceptive afferent fibers in a spinal nerve or its roots or by other neuropathic mechanisms, and may be episodic, recurrent, or sudden [59]. Clinically, there is a 30% rate of radicular symptoms during axial rotation in those with rotator instabilities [60]. Thus, radicular pain may also be a result of underlying cervical instability.

With capsular ligament laxity, hypertrophic facet joint changes occur (including osteophytosis) as cervical degeneration progresses, causing encroachment on cervical nerve roots as they exit the spine through the neural foramina. This condition is called cervical radiculopathy and manifests as stabbing pain, numbness, and/or tingling down the upper extremity in the area of the affected nerve root.

The neural foramina lie between the intervertebral disc and the joints of Luschka (uncovertebral joints) anteriorly and the facet joint posteriorly. Their superior and inferior borders are the pedicles of adjacent vertebral bodies. Cervical nerve roots there are vulnerable to compression or injury by the facet joints posteriorly or by the joints of Luschka and the intervertebral disc anteriorly.

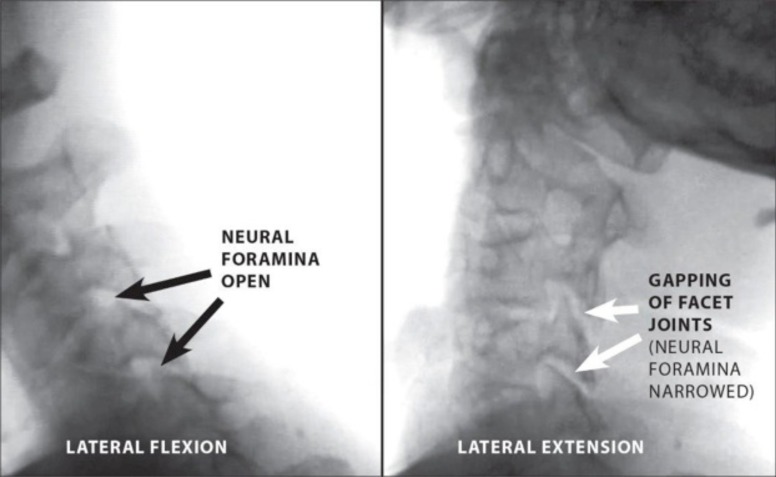

Cadaver studies have demonstrated that cervical nerve roots take up as much as 72% of the space in the neural foramina [61]. Normally, this provides ample room for the nerves to function optimally. However, if the cervical spine and capsular ligaments are injured, facet joint hypertrophy and degeneration of the cervical discs can occur. Over time, this causes narrowing of the neural foramina (Fig. 6) and a decrease in space for the nerve root. In the event of another ligament injury, instability of the hypertrophied bones can occur and further reduce the patency of the neural foramen.

Fig. (6).

Digital motion X-ray demonstrating multi-level cervical instability. Neural foraminal narrowing is shown at two levels during lateral extension versus lateral flexion.

Cervical radiculopathy from a capsular ligament injury typically produces intermittent radicular symptoms which become more noticeable when the neck is moved in a certain direction, such as during rotation, flexion or extension. These movements can cause encroachment on cervical nerve roots and subsequent paresthesia along the pathway therein of the affected nerve and may be why evidence of cervical radiculopathy does not show up on standard MRI or CT scans.

When disc herniation is the cause of cervical radiculopathy, it typically presents with acute onset of severe neck and arm pain unrelieved by any position and often results in encroachment on a cervical nerve root. While disc herniation can easily be seen on routine (non-functional) MRI or CT scans, evidence of radiculopathy from cervical instability cannot. Most cases of acute radiculopathy due to disc herniation resolve with non-surgical active or passive therapies, but some patients continue to have clinically significant symptoms, in which case surgical treatments such as anterior cervical decompression with fusion or posterior cervical laminoforaminotomy can be performed [62]. Cervical radiculopathy is also strongly associated with spondylosis, a disease generally attributed to aging that involves an overall degeneration of the cervical spine. The disorder is characterized by degenerative changes in the intervertebral disc, osteophytosis of the vertebral bodies, and hypertrophy of the facet joints and laminar arches. Since more than one cervical spine segment is usually affected in spondylosis, the symptoms of radiculopathy are more diffuse than those typical of unilateral soft disc herniation and present as neck, mid-upper back, and arm pain with paresthesia.

CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS: THE INSTABILITY CONNECTION

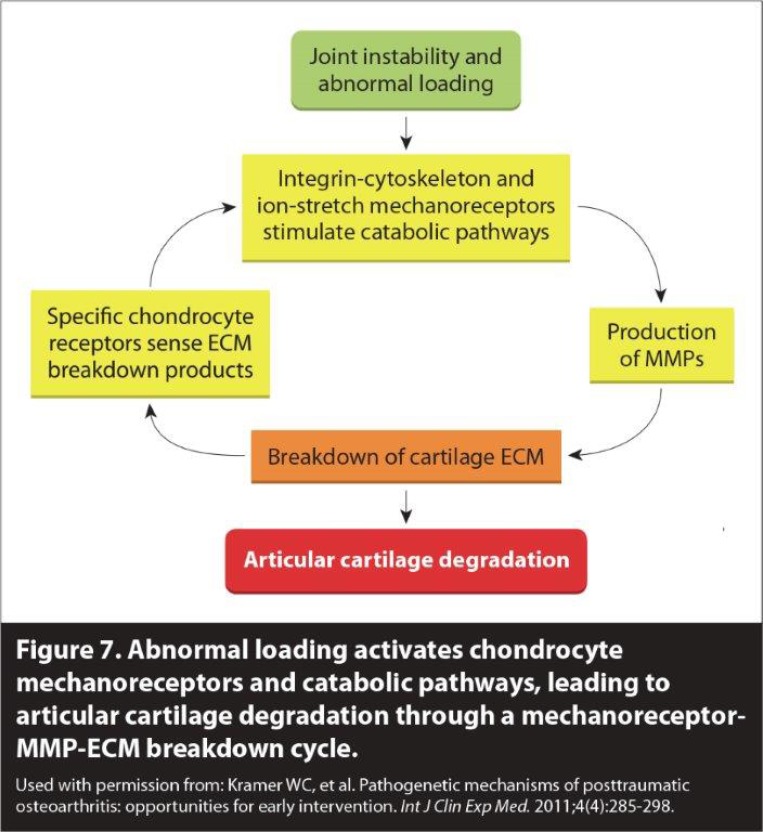

Spondylosis has previously been described as occurring in three stages: the dysfunctional stage, the unstable stage, and the stabilization stage (Fig. 7) [63]. Spondylosis begins with repetitive trauma, such as rotational strains or compressive forces to the spine. This causes injury to the facet joints which can compromise the capsular ligaments. The dysfunctional phase is characterized by capsular ligament injuries and subsequent cartilage degeneration and synovitis, ultimately leading to abnormal motion in the cervical spine. Over time, facet joint dysfunction intensifies as capsular laxity occurs. This stretching response can cause cervical instability, marking the unstable stage. During this progression, ongoing degeneration is occurring in the intervertebral discs, along with other parts of the cervical spine. Ankylosis (stiffening of the joints) can also occur at the unstable cervical spine segment, and rarely, causes entrapment of nearby spinal nerves. The stabilization phase occurs with the formation of marginal osteophytes as the body tries to heal the spine. These bridging bony deposits can lead to a natural fusion of the affected vertebrae [64].

Fig. (7).

Cervical OA: The 3 phases of the degenerative cascade. Used with permission from: Kramer WC, et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms of posttraumatic osteoarthritis: opportunities for early intervention. Int J Clin Exp Me d. 2011; 4(4): 285-298.

The degenerative cascade, however, begins long before symptoms become evident. Initially, spondylosis develops silently and is asymptomatic [65]. When symptoms of cervical spondylosis do develop, they are generally nonspecific and include neck pain and stiffness [66]. Only rarely do neurologic symptoms develop (ie, radiculopathy or myelopathy), and most often they occur in people with congenitally narrowed spinal canals [67]. Physical exam findings are often limited to restricted range of neck motion and poorly localized tenderness. Clinical symptoms commonly manifest when a new cervical ligament injury is superimposed on the underlying degeneration. In patients with spondylosis and underlying capsular ligament laxity, cervical radiculopathy is more likely to occur because the neural foramina may already be narrowed from facet joint hypertrophy and disc degeneration, enabling any new injury to more readily pinch on an exiting nerve root.

Thus, there are compelling reasons to believe that facet joint/capsular ligament injuries in the cervical spine may be an etiological basis for the degenerative cascade in cervical spondylosis and may be responsible for the attendant cervical instability. Animal models used for initiating disc degeneration in research studies have shown the induction of spinal instability through injury of the facet joints [68, 69]. In similar models, capsular ligament injuries of the facet joints caused multidirectional instability of the cervical spine, greatly increasing axial rotation motion correlating with cervical disc injuries [31, 28, 70, 71]. Using human specimens, surgical procedures such as discectomy have been shown to cause an immediate increase in motion of the segments involved [72]. Stabilization procedures such as neck fusion have been known to create increased pressure on the adjacent cervical spinal segments; this is referred to as adjacent segment disease. This can develop when the loss of motion from cervical fusion causes greater shearing and increased rotation and traction stress on adjacent vertebrae at the facet joints [73-75]. Thus, instability can “travel” up or down from the fused segment, furthering disc degeneration. These findings support the theory that iatrogenic-introduced stress and instability at adjacent spinal segments contribute to the pathogenesis of cervical spondylosis [74].

WHIPLASH TRAUMA

Damage to cervical ligaments from whiplash trauma has been well studied, yet these injuries are still often difficult to diagnose and treat. Standard x-rays often do not reveal present injury to the cervical spine and as a consequence, these injuries go unreported and patients are left without proper treatment for their condition [76]. Part of the difficulty lies in the fact that major injury to the cervical spine may only produce minor symptoms in some patients, whereas minor injury may produce more severe symptoms in others [77]. These symptoms include acute and/or chronic neck pain, headache, dizziness, vertigo and paresthesia in the upper extremities [78, 79].

MRI and autopsy studies have both shown an association between chronic symptoms in whiplash patients and injuries to the cervical discs, ligaments and facet joints [42, 80]. Success in relieving neck pain in whiplash patients has been documented by numerous clinical studies using nerve block and radiofrequency ablation of facet joint afferents, including capsular ligament nerves, such that increased interest has developed regarding the relationships between injury to the facet joints and capsular ligaments and post-whiplash dysfunction and related symptoms [36, 81].

Multiple studies have implicated the cervical facet joint and its capsule as a primary anatomical site of injury during whiplash exposure to the neck [55, 57, 82, 83]. Others have shown that injury to the cervical facet joints and capsular ligaments are the most common cause of pain in post-whiplash patients [84-86]. Cinephotographic and cineradiographic studies of both cadavers and human subjects show that under the conditions of whiplash, a resultant high impact force occurs in the cervical facet joints, leading to their injury and the possibility of cervical spine instability [84].

In whiplash trauma, up to 10 times more force is absorbed in the capsular ligaments versus the intervertebral disc [30]. Unlike the disc, the facet joint has a much smaller area in which to disperse this force. Ultimately, the capsular ligaments become elongated, resulting in abnormal motions in the spinal segments affected [30, 87]. This sequence has been documented with both in vitro and in vivo studies of segmental motion characteristics after torsional loads and resultant disc degeneration [88-90].

Injury to the facet joints and capsular ligaments has been further confirmed during simulated whiplash traumas [91]. Maximum capsular ligament strains occur during shear forces, such as when a force is applied while the head is rotated (axial rotation). While capsular ligament injury in the upper cervical spinal region can occur from compressive forces alone, exertion from a combination of shear, compression and bending forces is more likely and usually involves much lower loads to cause injury [92]. However, if the head is turned during whiplash trauma, the peak strain on the cervical facet joints and capsular ligaments can increase by 34% [93]. In one study reporting on an automobile rear-impact simulation, the magnitude of the joint capsule strain was 47% to 196% higher in instances when the head was rotated 60° during impact, compared with those when the head was forward facing [94]. The impact was greatest in the ipsilateral facet joints, such that head rotation to the left caused higher ligament strain at the left facet joint capsule.

In other simulations, whiplash trauma has been shown to reduce cervical ligament strength (ie, failure force and average energy absorption capacity) compared with controls or computational models [30, 87]; this is especially true in the case of capsular ligaments, since such trauma causes capsular ligament laxity. One study conclusively demonstrated that whiplash injury to the capsular ligaments resulted in an 85% to 275% increase in ligament elongation (ie, laxity) compared to that of controls [30]. The study also reported evidence that tension of the capsular ligaments is requisite for producing pain from the facet joint.

POST-CONCUSSION SYNDROME

Each year in the United States, approximately 1.7 million people are diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI), although many more go undiagnosed because they do not seek out medical care [95]. Of these, approximately 75% - 90% are diagnosed as having a concussion. A concussion is considered a mild TBI and is defined as any transient neurologic dysfunction resulting from a biomechanical force, usually a sudden or forceful blow to the head which may or may not cause a loss of consciousness. Concussion induces a barrage of ionic, metabolic, and physiologic events [96] and manifests in a composite of symptoms affecting a patient’s physical, cognitive, and emotional states, and his or her sleep cycle, any one of which can be fleeting or long-term in duration [97]. The diagnosis of concussion is made by the presence of any one of the following: (1) any loss of consciousness; (2) any loss of memory for events immediately before or after the injury; (3) any alteration in mental status at the time of the accident; (4) focal neurological deficits that may or may not be transient [98].

While most individuals recover from a single concussion, up to one-third of those will continue to suffer from residual effects such as headache, neck pain, dizziness and memory problems one year after injury [99]. Such symptoms characterize a disorder known as post-concussion syndrome (PCS) and are much like those of WAD; both disorders are likely due to cervical instability. According to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), the diagnosis of PCS is made when a person has had a head injury sufficient enough to result in loss of consciousness and develops at least three of eight of the following symptoms within four weeks: headache, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, sleep problems, concentration difficulties, memory issues, and problems tolerating stress [100, 101]. Of those treated for PCS who had mild head injury, 80% report having chronic daily headaches; surprisingly, of those with moderate to severe head injury, only 27% reported having chronic daily headaches [102]. The impact of the brain on the skull is believed to be the cause of the symptoms of both concussion and PCS, although the specific mechanisms underlying neural tissue damage are still being investigated.

PCS-associated symptoms also overlap with many symptoms common to WAD. This overlap in symptomology may be due to a common etiology of underlying cervical instability that affects the cervical spine near the neck. Data has revealed that over half of patients with damage to the upper cervical spine from whiplash injury had evidence of concurrent head trauma [103]. It was shown that whiplash can cause minor brain injuries similar to that of concussion if it occurs with such rapid neck movement that there is a collision between the brain and skull. Thus, one may conjecture that concussion involves a whiplash-type injury to the neck.

Despite unique differences in the biomechanics of concussion and whiplash, both types of trauma involve an acceleration-deceleration of the head and neck. This impact to the head can not only cause injury to the brain and skull, but can also damage surrounding ligaments of the neck since these tissues undergo the same accelerating-decelerating force. The acceleration-deceleration forces which occur during whiplash injury are staggering. Direct head trauma has been shown to produce forces between 10,000 and 15,000 N on the head and between 1,000 and 1,500 N on the neck, depending on the angle at which the object hits the head [104, 105]. Cervical capsular ligaments can become lax with as little as 5 N of force, although most studies report cervical ligament failure at around 100 N [30, 55, 91, 106]. Even low speed rear impact collisions at as little as 7 mph to 8 mph can cause the head to move roughly 18 inches at a force as great as 7 G in less than a quarter of a second [107]. Numerous experimental studies have suggested that certain features of injury mechanisms including direction and degree of acceleration and deceleration, translation and rotation forces, position and posture of head and neck, and even seat construction may be linked to the extent of cervical spine damage and to the actual structures damaged [23, 27, 35, 50, 61].

Debate over the veracity of PCS or WAD symptomology has persisted; however, there is no single explanation for the etiology of these disorders, especially since the onset and duration of symptoms can vary greatly among individuals. Many of the symptoms of PCS and WAD tend to increase over time, especially when those affected are engaged in physical or cognitive activity. Chronic neck pain is often described as a long-term result of both concussion and whiplash, indicating that the most likely structures to become injured during these traumas are the capsular ligaments of the cervical facet joints. In light of this, we propose that the best scientific anatomical explanation is cervical instability in the upper cervical spine, resulting from ligament injury (laxity).

VERTEBROBASILAR INSUFFICIENCY

The occipito-atlanto-axial complex has a unique anatomical relationship with the vertebral arteries. In the lower cervical spine, the vertebral arteries lie in a relatively straight-forward course as they travel through the transverse foramina from C3-C6. However, in the upper cervical spine the arteries assume a more serpentine-like course. The vertebral artery emerges from the transverse process of C2 and sweeps laterally to pass through the transverse foramen of C1 (atlas). From there it passes around the posterior border of the lateral mass of C1, at which point it is farthest from the midline plane at the level of C1 [108, 109]. This pathway creates extra space which allows for normal head rotation without compromising vertebral artery blood flow.

Considering the position of the vertebral arteries in the canals of the transverse processes in the cervical vertebrae, it is possible to see how head positioning can alter vertebral arterial flow. Even normal physiological neck movements (ie, neck rotation) have been shown to cause partial occlusion of up to 20% or 30% in at least one vertebral artery [110]. Studies have shown that contralateral neck rotation is associated with vertebral artery blood flow changes, primarily between the atlas and axis; such changes can also occur when osteophytes are present in the cervical spine [111, 112].

Proper blood flow in the vertebral arteries is crucial because these arteries travel up to form the basilar artery at the brainstem and provide circulation to the posterior half of the brain. When this blood supply is insufficient, vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) can develop and cause symptoms, such as neck pain, headaches/migraines, dizziness, drop attacks, vertigo, difficulty swallowing and/or speaking, and auditory and visual disturbances. VBI usually occurs in the presence of atherosclerosis or cervical spondylosis, but symptoms can also arise when there is intermittent vertebral artery occlusion induced by extreme rotation or extension of the head [113, 114]. This mechanical compression of the vertebral arteries can occur along with other anomalies, including cervical osteophytes, fibrous bands, and osseous prominences [115, 116] These anomalies were seen in about half of the cases of vertebral artery injury after cervical manipulation, as reported in a recent review [117].

Whiplash injury itself has been shown to reduce vertebral artery blood flow and elicit symptoms of VBI [118, 119]. In one study, the authors concluded that patients with persistent vertigo or dizziness after whiplash injury are likely to have VBI if the injury was traumatic enough to cause a circulation disorder in the vertebrobasilar arterial system [118]. Other researchers have surmised that excessive cervical instability, especially of the upper cervical spine, can cause obstruction of the vertebral artery during neck rotation, thus compromising blood flow and triggering symptoms [120-122].

BARRÉ- LIÉOU SYNDROME

A lesser known, yet relatively common, cause of neck pain is Barré-Liéou syndrome. In 1925, Jean Alexandre Barré, and in 1928, Yong Choen Liéou, each independently described a syndrome presenting with headache, orbital pressure/pain, vertigo, and vasomotor disturbances and proposed that these symptoms were related to alterations in the posterior cervical sympathetic chain and vertebral artery blood flow in patients who had cervical spine arthritis or other arthritic disorders [123, 124]. Barré-Liéou syndrome is also referred to as posterior cervical syndrome or posterior cervical sympathetic syndrome because the condition is now presumed to develop more from disruption of the posterior cervical sympathetic nervous system, which consists of the vertebral nerve and the sympathetic nerve network surrounding it. Symptoms include neck pain, headaches, dizziness, vertigo, visual and auditory disturbances, memory and cognitive impairment, and migraines. It has been surmised that cervical arthritis or injury provokes an irritation of both the vertebral and sympathetic nerves. As a result, current treatment now centers on resolution of cervical instability and its effects on the posterior sympathetic nerves [124]. Other research has found an association between the sympathetic symptoms of Barré-Liéou and cervical instability and has documented successful outcomes in case reports when the instability was addressed by various means including prolotherapy [125].

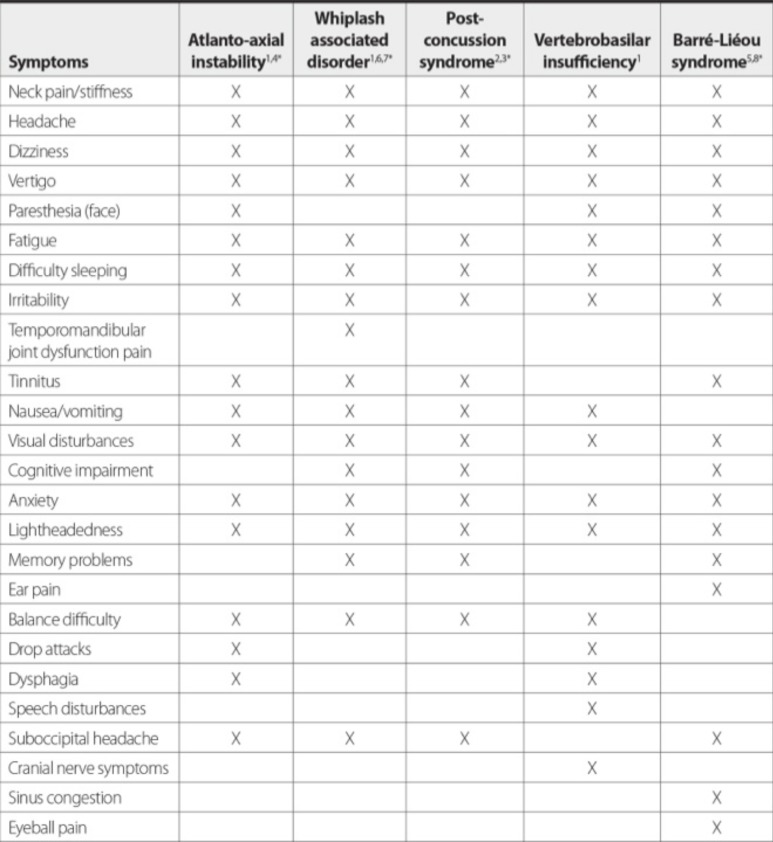

Symptoms of Barré-Liéou syndrome also appear to develop after trauma. In one study, 87% of patients with a diagnosis of Barré-Liéou syndrome reported that they began experiencing symptoms after suffering a cervical injury, primarily in the mid-cervical region [126]; in a related study, this same region was found to exhibit more instability than other spinal segments [127] The various symptoms that characterize Barré-Liéou syndrome can also mimic symptoms of PCS or WAD, [128] which can pose a challenge for practitioners in making a definitive diagnosis (Fig. 8). The diagnosis of Barré-Liéou syndrome is made on clinical grounds, as there is yet to be a definitive test to document irritation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Fig. (8).

Overlap in chronic symptomology between atlanto-axial instability, whiplash associated disorder, post-concussion syndrome, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and Barré-Liéou syndrome. There is considerable overlap in symptoms amongst these conditions, possibly because they all appear to be due to cervical instability.

1. Meadows J, Armijo-Olivo S, Magee D. Cervical Spine. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 5 ed: Saunders Elsevier; 2008: 17-44.

2. Leddy J, Sandhu H, Sodhi V, Baker J, Wilier B. Rehabilitation of concussion and post-concussion syndrome. Sports Health. 2012; 4(2): 147-154.

3. Boake C, McCauley SR, Levin HS, et al. Diagnostic criteria for postconcussional syndrome after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005; 17: 350-356.

4. Swinkels RA, Oostendorp RA. Upper cervical instability: fact or fiction. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1996; 19(3): 185-194.

5. Tamura T. Cranial symptoms after cervical injury. Aetiology and treatment of the BarrÉ-LiÉou Syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989; 71 B: 282-287.

6. Chen HB, Yang KH, Wang ZG. Biomechanics of whiplash injury. Chin J Traumata/. 2009; 12(5): 305-314.

7. Endo K, lchimaru K, Komagata M, Yamamoto K. Cervical vertigo and dizziness after whiplash injury. fur Spine J. 2006; 15: 886-890.

8. Pearce J. BarrÉ-LiÉou "syndrome". J Neural Neurosurg Psychol 2004; 75(2).

•Also based on the evaluation and treatment of thousands of patients at Caring Medical and Rehabilitation Services in Oak Park, IL over a 20 year period.

OTHER SOURCES OF CERVICAL PAIN

Various tensile forces place strains with differing deformations on a variety of viscoelastic spinal structures, including the ligaments, the annulus and nucleus of the intervertebral disc, and the spinal cord. Further to this, cadaver experiments have shown that the spinal cord and the intervertebral disc components carry considerably lower tensile forces than the spinal ligament column [129, 130]. Encapsulated mechanoreceptors and free nerve endings have been identified in the periarticular tissues of all major joints of the body including those in the spine, and in every articular tissue except cartilage [131]. Any innervated structure that has been injured by trauma is a potential chronic pain generator; this includes the intervertebral discs, facet joints, spinal muscles, tendons and ligaments [132-134].

The posterior ligamentous structures of the human spine are innervated by four types of nerve endings: pacinian corpuscles, golgi tendon organs, and ruffini and free nerve endings [40]. These receptors monitor joint excursion and capsular tension, and may initiate protective muscular reflexes that prevent joint degeneration and instability, especially when ligaments, such as the anterior and posterior longitudinal, ligamentum flavum, capsular, interspinous and supraspinous, are under too much tension [131, 135]. Collectively, the cervical region of the spinal column is at risk to sustain deformations at all levels and in all components, and when the threshold crosses a particular level at a particular component, injury is imminent owing to the relative increased flexibility or joint laxity.

OTHER SOURCES OF TRAUMA

As described earlier, the nucleus pulposus is designed to sustain compression loads and the annulus fibrosus that surrounds it, to resist tension, shear and torsion. The stress in the annulus fibers is approximately 4-5 times the applied stress in the nucleus [136, 137]. In addition, annulus fibers elongate by up to 9% during torsional loading, but this is still well below the ultimate elongation at failure of over 25% [138]. Pressure within the nucleus is approximately 1.5 times the externally applied load per unit of disc area. As such, the nucleus is relatively incompressible, which causes the intervertebral disc to be susceptible to injury in that it bulges under loads - approximately 1 mm per physiological load [139]. As the disc degenerates on bulging (herniates), it looses elasticity, further compromising its ability to compress. Shock absorption is no longer spread or absorbed evenly by the surrounding annulus, leading to greater shearing, rotation, and traction stress on the disc and adjacent vertebrae. The severity of disc herniation can range from protrusion and bulging of the disc without rupture of the annulus fibrosus to disc extrusion, in which case, the annulus is perforated, leading to tearing of the structure.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

There are a number of treatment modalities for the management of chronic neck pain and cervical instability, including injection therapy, nerve blocks, mobilization, manipulation, alternative medicine, behavioral therapy, fusion, and pharmacologic agents such as NSAIDS and opiates. However, these treatments do not address stabilizing the cervical spine or healing ligament injuries, and thus, do not offer long-term curative options. In fact, cortisone injections are known to inhibit, rather than promote healing. As mentioned earlier in this paper, most treatments have shown limited evidence in their efficacy or are inconsistent in their results. In a systematic review of the literature from January 2000 to July 2012 on physical modalities for acute to chronic neck pain, acupuncture, laser therapy, and intermittent traction were found to provide moderate benefits [5].

The literature contains many reports on injection therapy for the treatment of chronic neck pain. Cervical interlaminar epidural injections with or without steroids may provide significant improvement in pain and function for patients with cervical disc herniation and radiculitis [140]. As a

follow-up to its one-year results, a randomized, double-blind controlled trial found that the clinical effectiveness of therapeutic cervical medial branch blocks with or without steroids in managing chronic neck pain of facet joint origin provided significant improvement over a period of 2 years [141].

However, many other studies have had more nebulous results. In a systematic review of therapeutic cervical facet joint interventions, the evidence for both cervical radiofrequency neurotomy and cervical medial branch blocks is fair, and for cervical intra-articular injections with local anesthetic and steroids, the evidence is limited [142]. In a later corresponding systematic review, the same group of authors concluded that the strength of evidence for diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks is good (≥75% pain relief), but stated the evidence is limited for dual blocks (50% to 74% pain relief), as well as for single blocks (50% to 74% pain relief) and (≥75% pain relief.) [6]. In another systematic review evaluating cervical interlaminar epidural injections, the evidence indicated that the injection therapy showed significant effects in relieving chronic intractable pain of cervical origin; specific to long-term relief the indicated level of evidence was Level II-1 [143].

In the case of manipulative therapy, the results of a randomized trial disputed the hypothesis that supervised home exercises, combined or not with manual therapy, can be of benefit in treating non-specific chronic neck pain, as compared to no treatment [7]. The study found that there were no differences in primary or secondary outcomes among the three groups and that no significant change in health-related quality of life was associated with the preventive phase. Participants in the combined intervention group did not have less pain or disability and fared no better functionally than participants from the two other groups during the preventive phase of the trial. Another randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of applying joint mobilization at symptomatic and asymptomatic cervical levels in patients with chronic nonspecific neck pain was inconclusive in that there was no significant difference in pain intensity immediately after treatment between groups during resting position, painful active movement, or vertebral palpation [8]. Massage therapy had similar inconclusive results. Evidence was reported as “not strong” [144] in one randomized trial comparing groups receiving massage treatment for neck pain versus those reading a self-care book, while another found that cupping massage was no more effective than progressive muscle relaxation in reducing chronic non-specific neck pain [9]. Acupuncture appears to have better results in relieving neck pain but leaves questions as to the effects on the autonomic nervous system, suggesting that acupuncture points per se have different physical effects according to location [145].

Cervical disc herniation is a major source of chronic neck and spinal pain and is generally treated by either surgery or epidural injections, but their effectiveness continues to be debatable. In a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial assigning patients to treatment with epidural injections with lidocaine or lidocaine mixed with betamethasone, 72% of patients in the local anesthetic group and 68% of patients in the local anesthetic with steroid group had at least a 50% improvement in pain and disability at 2 years, indicating that either protocol may be beneficial in alleviating chronic pain from cervical disc herniation [146].

In a systematic review of pharmacological interventions for neck pain, Peloso, et al. [147] reported that, aside from evidence in one study of a small immediate benefit for the psychotropic agent eperison hydrochloride (a muscle relaxant), most studies had low to very low quality methodologic evidence. Furthermore, they found evidence against a long-term benefit for medial branch block of facet joints with steroids and against a short-term benefit for botulinum toxin-A compared to saline, concluding that there is a lack of evidence for most pharmacological interventions.

Collectively, these interventions for the treatment of chronic neck pain may each offer temporary relief, but many fall short of a cure. Aside from these conventional treatment options, there are pain medications and pain patches, but their use is controversial because they offer little restorative value and often lead to dependence. If joint instability is the fundamental problem causing chronic neck pain and its associated autonomic symptoms, prolotherapy may be a treatment approach that meets this challenge.

PROLOTHERAPY FOR CERVICAL INSTABILITY

To date, there is no consensus on the diagnosis of cervical spine instability or on traditional treatments that relieve chronic neck pain. In such cases, patients often seek out alternative treatments for pain and symptom relief. Prolotherapy is one such treatment which is intended for acute and chronic musculoskeletal injuries, including those causing chronic neck pain related to underlying joint instability and ligament laxity (Fig. 9).

Fig. (9).

Stress-strain curve for ligaments and tendons. Ligaments can withstand forces and revert back to their original position up to Point C. At this point, prolotherapy treatment may succeed in tightening the tissue. Once the force continues past Point C. the ligament becomes permanently elongated or stressed.

Chronic neck pain and cervical instability are particularly difficult to treat when capsular ligament laxity is the cause because ligament cartilage is notoriously slow in healing due to a lack of blood supply. Most treatment options do not address this specific problem, and therefore, have limited success in providing a long-term cure.

Whiplash is a prime example because it often results in ligament laxity. In a five-part series evaluating the strength of evidence supporting WAD therapies, Teasell, et al. [10, 148-151] report that there is insufficient evidence to support any treatment for subacute WAD, stating that radiofrequency neurotomy may be the most effective treatment for chronic WAD. Furthermore, they state that immobilization with a soft collar is ineffective to the point of impeding recovery, saying that activation-based therapy is recommended instead, a conclusion similar to that of Hauser et al. [40] For chronic WAD, exercise programs were the most effective noninvasive treatment and radiofrequency neurotomy, the most effective of surgical or injection-based interventions, although evidence was not strong enough to establish the efficacy of any one treatment [10].

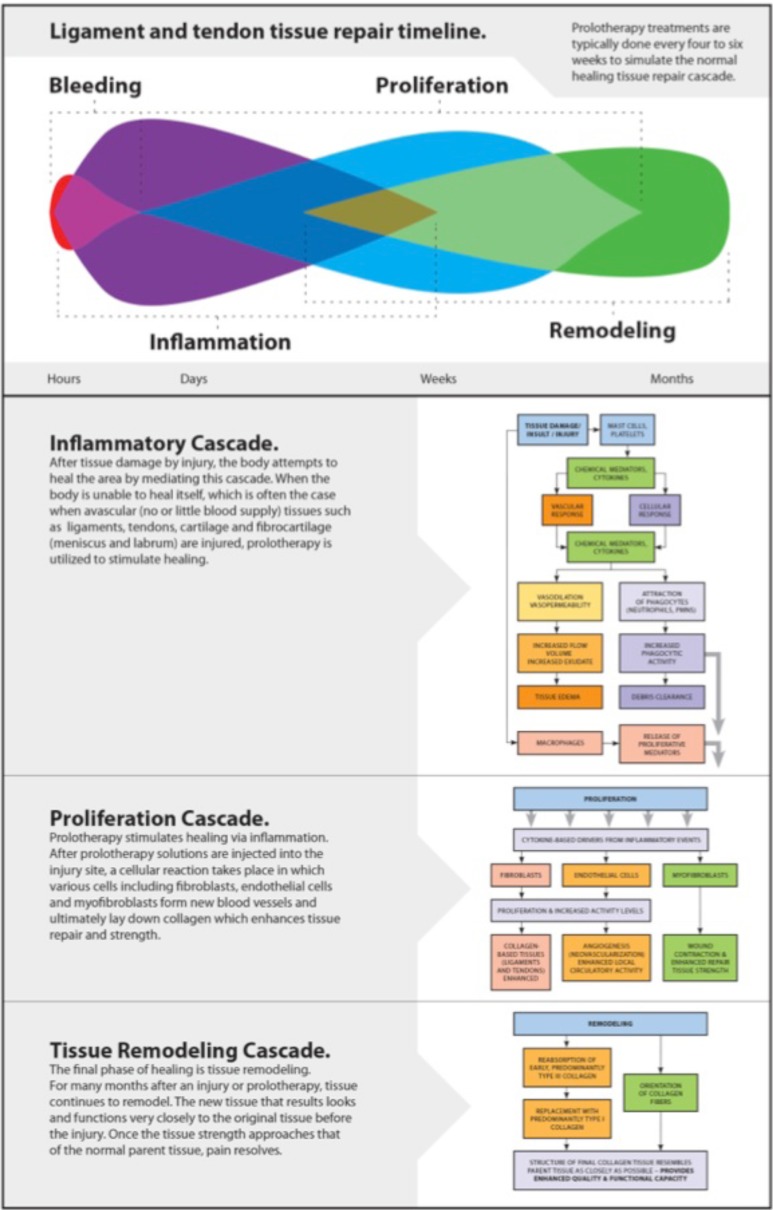

Prolotherapy is referred to as a regenerative injection technique (RIT) because it is based on the premise that the regenerative/reparative healing process consists of three overlapping phases: inflammatory, proliferative with granulation, and remodeling with contraction (Fig. 10) [152]. The prolotherapy technique involves injecting an irritating solution (usually a dextrose/sugar solution) at painful ligament and tendon attachment sites to produce a mild inflammatory response. Such a response initiates a healing cascade that duplicates the natural healing process of poorly vascularized tissue (ligaments, tendons, and cartilage) [40, 153]. In doing so, tensile strength, elasticity, mass and load-bearing capacity of collagenous connective tissues become increased [152]. This occurs because the increased glucose concentration causes increases in cell protein synthesis, DNA synthesis, cell volume, and proliferation, all of which stimulate ligament size and mass and ligament-bone junction strength, as well as the production of growth factors, which are essential for ligament repair and growth [154].

Fig. (10).

The biology of prolotherapy.

While the most studied type of prolotherapy is the Hackett-Hemwall procedure which uses dextrose as the proliferant, there are multiple other choices that are suitable, such as polidocanol, manganese, human growth hormone, and zinc. In addition to the Hackett-Hemwall procedure, there is another procedure called cellular prolotherapy, which involves the use of a patient’s own cells from blood, bone marrow, or adipose tissue as the proliferant to generate healing.

It is important to note that prolotherapy not only involves the treatment of joints, but also the associated tendon and ligament attachments surrounding them; hence, it is a comprehensive and highly effective means of wound healing and pain resolution. The Hackett-Hemwall prolotherapy technique was developed in the 1950s and is being transitioned into mainstream medicine due to an increasing number of studies reporting positive outcomes [155-158].

Prolotherapy has a long history of being used for whiplash-type soft tissue injuries of the neck. In separate studies, Hackett and his colleagues early on had remarkably successful outcomes in treating ligament injuries; more than 85% of patients with cervical ligament injury-related symptoms, including those with headache or WAD, reported they had minor to no residual pain or related symptoms after prolotherapy [125, 159, 160]. Similar favorable outcomes for resolving neck pain were reported recently by Hauser, et al. [161]. Hooper, et al. also reported on a case series [162] in which patients with whiplash received intra-articular injections (prolotherapy) into each zygapophysial (facet)

joint and attained consistently improved scores in the Neck Disability Index (NDI) at 2, 6 and 12 months post treatment; average change in Neck Disability Index (NDI) was significant (13.77; p < 0.001) at baseline versus 12 months. Specific to cervical instability, Centeno, et al. [163] performed fluoro-scopically guided prolotherapy and reported that stabilization of the cervical spine with prolotherapy correlated with symptom relief, as depicted in blinded pre and post radiographic readings. Prolotherapy has also been found effective for other ligament injuries, including the lower back, [164-166] knee, [167-169] and other peripheral joints, [170-172] as well as congenital systemic ligament laxity conditions [173].

Evidence that prolotherapy induces the repair of ligaments and other soft tissue structures has been reported in both animal and human studies. Animal research conducted by Hackett [174] demonstrated that proliferation and strengthening of tendons occurred, while Liu and associates [175] found that prolotherapy injections to rabbit ligaments increased ligamentous mass (44%), thickness (27%), as well as ligament-bone junction strength (28%) over a six-week period. In a study on human subjects, Klein et al. [176] used electron microscopy and found an average increase in ligament diameter from 0.055 µm to 0.087 µm after prolotherapy, as shown in biopsies of posterior sacroi-liac ligaments. They also found a linear ligament orientation similar to what is found in normal ligaments. In a case study, Auburn, et al. [177] documented a 27% increase in iliolum-bar ligament size after prolotherapy, via ultrasound.

Studies have also been published on the use of prolotherapy for resolving chronic pain, [152, 178, 179] as well as for conditions specifically related to joint instability in the cervical spine [163, 180] In our own pain clinic, we have used prolotherapy successfully on patients who had chronic pain in the shoulder, elbow, low back, hip, and knee [181-186].

CONCLUSION

The capsular ligaments are the main stabilizing structures of the facet joints in the cervical spine and have been implicated as a major source of chronic neck pain. Such pain often reflects a state of instability in the cervical spine and is a symptom common to a number of conditions such as disc herniation, cervical spondylosis, whiplash injury and whiplash associated disorder, postconcussion syndrome, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and Barré-Liéou syndrome.

When the capsular ligaments are injured, they become elongated and exhibit laxity, which causes excessive movement of the cervical vertebrae. In the upper cervical spine (C0-C2), this can cause symptoms such as nerve irritation and vertebrobasilar insufficiency with associated vertigo, tinnitus, dizziness, facial pain, arm pain, and migraine headaches. In the lower cervical spine (C3-C7), this can cause muscle spasms, crepitation, and/or paresthesia in addition to chronic neck pain. In either case, the presence of excessive motion between two adjacent cervical vertebrae and these associated symptoms is described as cervical instability.

Therefore, we propose that in many cases of chronic neck pain, the cause may be underlying joint instability due to

capsular ligament laxity. Furthermore, we contend that the use of comprehensive Hackett-Hemwall prolotherapy appears to be an effective treatment for chronic neck pain and cervical instability, especially when due to ligament laxity. The technique is safe and relatively non-invasive as well as efficacious in relieving chronic neck pain and its associated symptoms. Additional randomized clinical trials and more research into its use will be needed to verify its potential to reverse ligament laxity and correct the attendant cervical instability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Ms. Woldin and Ms. Sawyer have nothing to declare. Dr. Hauser and Ms. Steilen declare that they perform prolotherapy at Caring Medical Rehabilitation Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Childs J, Cleland J, Elliott J , et al. Neck pain clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9): A1–34. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Kristman V. The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population a population based cohort study. Pain. 2004;112(3): 267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg-Johnson S, van der Velde G, Carroll LJ , et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(Suppl 1 ): 39–51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW , et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify patients with low back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation a validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12): 920–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham N, Gross AR, Carlesso LC , et al. ICON. An ICON overview on physical modalities for neck pain and associated disorders. Open Orthop J. 2013;7(Suppl 4 ): 440–60. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onyewu O, Manchikanti L, Falco FJE , et al. An update of the appraisal of the accuracy and utility of cervical discography in chronic neck pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15: E777–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martel J, Dugas C, Dubois JD, Descarreaux M. A randomised controlled trial of preventive spinal manipulation with and without a home exercise program for patients with chronic neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12: 41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aquino RL, Caires PM, Furtado FC, Loureiro AV, Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML. Applying joint mobilization at different cervical vertebral levels does not influence immediate pain reduction in patients with chronic neck pain a randomized clinical trial. J Manual Manipulative Ther. 2009;17(2): 95–100. doi: 10.1179/106698109790824686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauche R, Materdey S, Cramer H , et al. Effectiveness of home-based cupping massage compared to progressive muscle relaxation in patients with chronic neck pain-a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6): e65378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teasell RW, McClure JA, Walton D , et al. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 1 - overview and summary. Pain Res Manage. 2010;15(5): 287–94. doi: 10.1155/2010/106593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL. Application of a diagnosis-based clinical decision guide in patients with neck pain. Chiropr Manual Ther. 2011;19: 19. doi: 10.1186/2045-709X-19-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki F, Fukami T, Tsuji A, Takagi K, Matsuda M. Discrepancies of MRI findings between recumbent and upright positions in atlantoaxial lesion. Report of two cases. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(Suppl 2 ): S304–7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0595-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Röijezon U, Djupsjöbacka M, Björklund M, Häger-Ross C, Grip H, Liebermann DG. Kinematics of fast cervical rotations in persons with chronic neck pain a cross-sectional and reliability study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11: 22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelalis ID, Christoforou G, Arnaoutoglou CM, Politis AN, Manoudis G, Xenakis TA. Misdiagnosed bilateral C5-C6 dislocation causing cervical spine instability a case report. Cases J. 2009;2: 6149. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor M, Hipp JA, Gertzbein SD, Gopinath S, Reitman CA. Observer agreement in assessing flexion-extension X-rays of the cervical spine, with and without the use of quantitative measurements of intervertebral motion. Spine J. 2007;7(6): 654–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windsor RE. Cervical spine anatomy. http: //emedicine.medscape. com/article/1948797-overview#a30 [Accessed April 14. 2014.

- 17.Driscoll DR. Anatomical and biomechanical characteristics of upper cervical ligamentous structures a review. J Manipulative and Physiol Ther. 1987;10(3): 107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusick JF, Yoganandan N. Biomechanics of the cervical spine part 4: major injuries. Clin Biomech. 2002;17(1): 1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachemson A. The influence of spinal movements of the lumbar intradiscal pressure on the tensile stresses in the annulus fibrosus. Acta Orthop Scan. 1963;33: 183–207. doi: 10.3109/17453676308999846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zak M, Pezowicz C. Spinal sections and regional variations in the mechanical properties of the annulus fibrosus subjected to tensile loading. Acta Bioeng Biomech. 2013;15(1): 51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercer S, Bogduk N. The ligaments and annulus fibrosus of human adult cervical intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(7): 619–28. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuri J, Stapleton E. The spine at trial practical medicolegal concepts about the spine. http: //books.google.com/books?id=Gi6w jdftC7cC&pg=PA12&lpg=PA12&dq=cervical+spine+transverse+processes&source=bl&ots=tboGEQAnuB&sig=Vi4bIDA24bLxGWWEivgAmmlETFo&hl=en&sa=X&ei=YETZUteXHMTAyAGNkICIBQ&ved=0CDYQ6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q=cervical%20spine%20transverse%20processes&f=false [Accessed April 14. 2014.

- 23.Jaumard N, Welch WC, Winkelstein BA. Spinal facet joint biomechanics and mechanotransduction in normal, injury, and degenerative conditions. J Biomech Eng. 2011;133(7): 071010. doi: 10.1115/1.4004493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volle E. Functional magnetic resonance imaging video diagnosis of soft-tissue trauma to the craniocervical joints and ligaments. Int Tinnitus J. 2000;6(2): 134–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pal GP, Routal RV, Saggu KG. The orientation of the articular facets of the zygapophyseal joints at the cervical and upper thoracic region. J Anat. 2001;198(Pt 4): 431–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19840431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn KP, Lee KE, Ahaghotu CC, Winkelstein BA. Structural changes in the cervical facet capsular ligament potential contributions to pain following subfailure loading. Stapp Car Crash J. 2007;51: 169–87. doi: 10.4271/2007-22-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panjabi MM, Bibu K, Cholewicki J. Whiplash injuries and the potential for mechanical instability. Eur Spine J. 1998;7: 484–92. doi: 10.1007/s005860050112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zdeblick TA, Abitbol JJ, Kunz DN, McCabe RP, Garfin S. Cervical stability after sequential capsule resection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18: 2005–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasoulinejad P, McLachlin SD, Bailey SI, Gurr KR, Bailey CS, Dunning CE. The importance of the posterior osteoligamentous complex to subaxial cervical spine stability in relation to a unilateral facet injury. Spine J. 2012;12(7): 590–5. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivancic PC, Coe MP, Ndu AB , et al. Dynamic mechanical properties of intact human cervical spine ligaments. Spine J. 2007;7(6): 659–65. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeVries NA, Gandhi AA, Fredericks DC, Grosland NM, Smucker JD. Biomechanical analysis of the intact and destabilized sheep cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(16): E957–63. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182512425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crisco JJ, 3rd, Oda T, Panjabi MM, Bueff HU, Dvorák J, Grob D. Transections of the C1-C2 joint capsular ligaments in the cadaveric spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16: S474–9. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199110001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadeau M, McLachlin SD, Bailey SI, Gurr KR, Dunning CE, Bailey CS. A biomechanical assessment of soft-tissue damage in the cervical spine following a unilateral facet injury. J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94(21): e156. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank CB. Ligament structure, physiology, and function. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2004;4(2): 199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen HB, Yang KH, Wang ZG. Biomechanics of whiplash injury. Chin J Traumatol. 2009;12(5): 305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boswell MV, Colson JD, Sehgal N, Dunbar EE, Epter R. A systematic review of therapeutic facet joint interventions in chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2007;10(1): 229–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aprill C, Bogduk N. The prevalence of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain a first approximation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17: 744–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. The prevalence of cervical zygapophaseal joint pain after whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20: 20–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLain RF. Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints. Iowa Orthop J. 1993;13: 149–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauser RA, Dolan EE, Phillips HJ, Newlin AC, Moore RE Woldin BA. Ligament injury and healing a review of current clinical diagnostics and therapeutics. Open Rehabil J. 2013;6: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergmann TF, Peterson DH. Chiropractic technique principles and procedures, 3rd ed. New York Mobby Inc. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jónsson H , Jr, Bring G, Rauschning W, Sahlstedt B. Hidden cervical spine injuries in traffic accident victims with skull fractures. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4(3): 251–63. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Mameren H, Drukker J, Sanches H, Beursgens J. Cervical spine motion in the sagittal plane (I) range of motion of actually performed movements, an x-ray cinematographic study. Eur J Morphol. 1990;28(1): 47–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Mameren H, Sanches H, Beursgens J, Drukker J. Cervical spine motion in the sagittal plane II positions of segmental averaged instantaneous centers of rotation-a cineradiographic study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17(5): 467–74. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bogduk N, Mercer S. Biomechanics of the cervical spine 1: normal kinematics. Clin Biomech. 2000;15(9): 633–48. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(00)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radcliff K, Kepler C, Reitman C, Harrop J, Vaccaro A. CT and MRI-based diagnosis of craniocervical dislocations the role of the occipitoatlantal ligament. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2012;70(6): 1602–13. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2151-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hino H, Abumi K, Kanayama M, Kaneda K. Dynamic motion analysis of normal and unstable cervical spines using cineradiography.an in vivo study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(2): 163–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199901150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]