The goal of this study was to identify the extent to which national treatment guidelines are being used in the People’s Republic of China to customize patient care in lung cancer and to analyze the reasons for treatment disparities. The results demonstrated large disparities in the treatment of lung cancer in China

Keywords: Lung cancer, Treatment disparity, Retrospective studies, People’s Republic of China

Abstract

Background.

Substantial progress has been made in the treatment of malignancies in the People’s Republic of China in recent years. The goal of this study was to identify the extent to which national treatment guidelines are being used to customize patient care in lung cancer and to analyze the reasons for treatment disparities.

Methods.

Patient characteristics and treatments were investigated retrospectively for the period from October 2004 to January 2013 using the outpatient database of the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute (GLCI) in China.

Results.

A total of 2,535 outpatients with lung cancer were studied in this retrospective analysis. The treatment disparity was 45.3%. Overall, 20.6% of patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were overtreated, and 20.1% of stage II patients were undertreated. Only 19.6% of stage IIIA patients and 30.7% of stage IIIB patients underwent the recommended combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, respectively. For advanced NSCLC, the greatest treatment disparity appeared in the second-line setting and beyond. Patients who were positive for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and receiving EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors experienced significant prolongation of survival compared with patients who were EGFR negative or whose EGFR mutation status was unknown (hazard ratio: 0.79; p = .037). The treatment disparities were significantly larger among patients aged younger than 65 years and in patients from developing regions compared with patients aged 65 years and older and from developed regions, respectively (p < .001, p = .046). The difference in treatment disparity was statistically significant between GLCI and other hospitals (p < .001).

Conclusion.

This retrospective study of a large number of patients from an outpatient oncology database demonstrated large disparities in the treatment of lung cancer in China. It is important to develop a new guideline for recommendations that are based on resource classification.

Implications for Practice:

Substantial progress has been made in the treatment of lung cancer in the People's Republic of China in recent years. This retrospective study based on the outpatient database of Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute in China, demonstrated large disparities in lung cancer care in China. These disparities are an issue not only of innate biological factors but also of modifiable characteristics of individual behavior and decision making as well as characteristics of the patient health system. China needs to develop a new guideline for recommendations that are based on resource classifications (basic to maximal).

Introduction

Lung cancer accounts for the largest number of cancer-related deaths in the People’s Republic of China and throughout the world [1]. Because lung cancer therapy requires the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team to combine various therapeutic approaches, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and molecularly targeted therapy, it is important to develop and implement sound multidisciplinary evidence-based guidelines. Some studies have shown that good guidelines can improve disease care [2, 3]. Jakobsen et al. reported that Denmark developed a complete set of national guidelines for lung cancer in 1998 and then established a national registry 2 years later to document the degree of agreement between the recommendations and clinical practice [2]. They found that 2-year overall survival (OS) of lung cancer improved from 50% in 2000 to 60% in 2007. They concluded that the adoption of evidence-based and guideline-recommended treatments is probably the best and only way to significantly improve the treatment of lung cancer. Johnson et al. in the U.S. also showed that rural residents did not show poorer survival when treatment was controlled [4].

Under the leadership of the Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Expert Panel of the Chinese Ministry of Health, China published its first evidence-based lung cancer guidelines in 2003 and issued a revision in 2011 [5]. Ensuring that guideline-recommended treatments are prescribed consistently across different geographic areas is critical and requires coordination across multiple providers and health care settings. China’s huge population, expansive geography, and diverse socioeconomic backgrounds produce wide disparities in lung cancer care. In developed regions, such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou, the quality of oncology services is similar to that in Western countries. However, in low-income areas, such as Gansu, Ningxia, and Tibet, many lung cancer patients are unable to receive even basic anticancer treatment.

Siegel et al. estimate that if everyone in the U.S. experienced the same overall cancer death rates as the most educated non-Hispanic whites, 37% of premature cancer deaths could potentially be avoided [6]. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services made it clear that elimination of health disparities was a national priority [7]. If cancer patients receive less-than-standard treatment, differences in outcomes are likely to result [8]. Reducing these disparities is a critical next step for China.

The main purpose of this retrospective study was to identify the extent to which national treatment guidelines are being used to customize patient care in lung cancer and to analyze the reasons for treatment disparities. Finally, we make recommendations across resource classifications (basic to maximal) to take into account of the diversity of settings in China.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

Clinical data of patients with lung cancer in this retrospective, observational survey were obtained from an electronic outpatient database at the Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute (GLCI) in China for the period from October 2004 to January 2013.

Data Collection

The extracted information included patient number, age, sex, identification number, address, smoking history, histological type, stage classification, genetic status, treatment condition, and hospital category (“GLCI,” “university hospitals,” “tumor hospitals,” and “other”). Smoking history was self-reported. “Never-smokers” were defined as patients who had smoked <100 cigarettes over their lifetime. Stage classification was defined according to the sixth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM classification through July 31, 2009, and according to the seventh edition from August 1, 2009. The treatments included surgery, perioperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy, first- to fifth-line chemotherapy, and molecularly targeted therapy.

Based on the Chinese lung cancer guidelines, the current standard of care for patients with stage I to resectable stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and stage I small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is surgical treatment. Platinum-based chemotherapy is offered as postoperative adjuvant therapy in patients with stage II to stage III NSCLC. The recommended therapy for patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC is concurrent chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy. The therapeutic strategy for advanced lung cancer is systemic treatment, including molecularly targeted treatment and chemotherapy. Treatment disparity was defined as treatment that did not follow the Chinese lung cancer guidelines, including perioperative chemotherapy that was or was not applied for resectable tumors; the combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy that was or was not applied for locally advanced tumors; molecularly targeted therapy that was or was not applied based on mutation status and so on.

Statistical Analysis

Median, mean (standard deviation), or count (percentage) was used to present the data. The relationships between treatment disparities with clinical characteristics and geographical distribution of patients or treatment hospitals were analyzed with the chi-square test. OS was measured from the day of diagnosis of lung cancer. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to obtain hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to estimate treatment disparity of molecularly targeted therapy. All statistical tests were two-sided p tests. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software, version 16.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, http://www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss/).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Patients

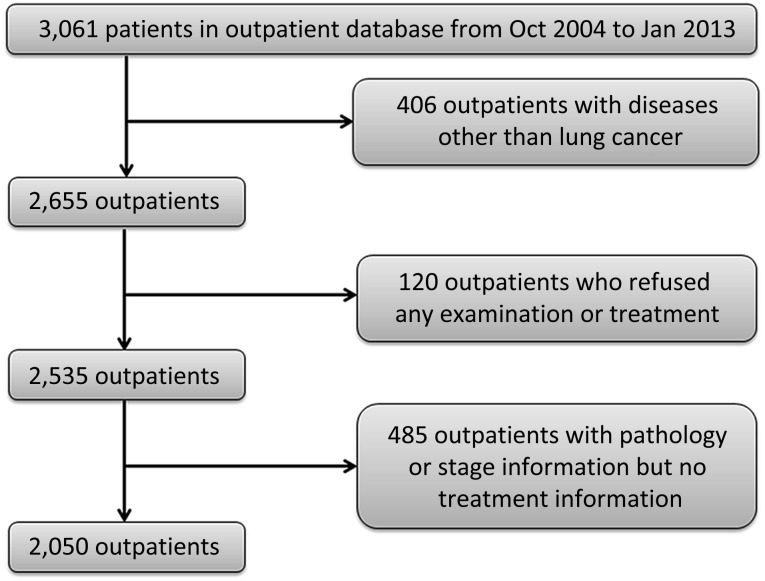

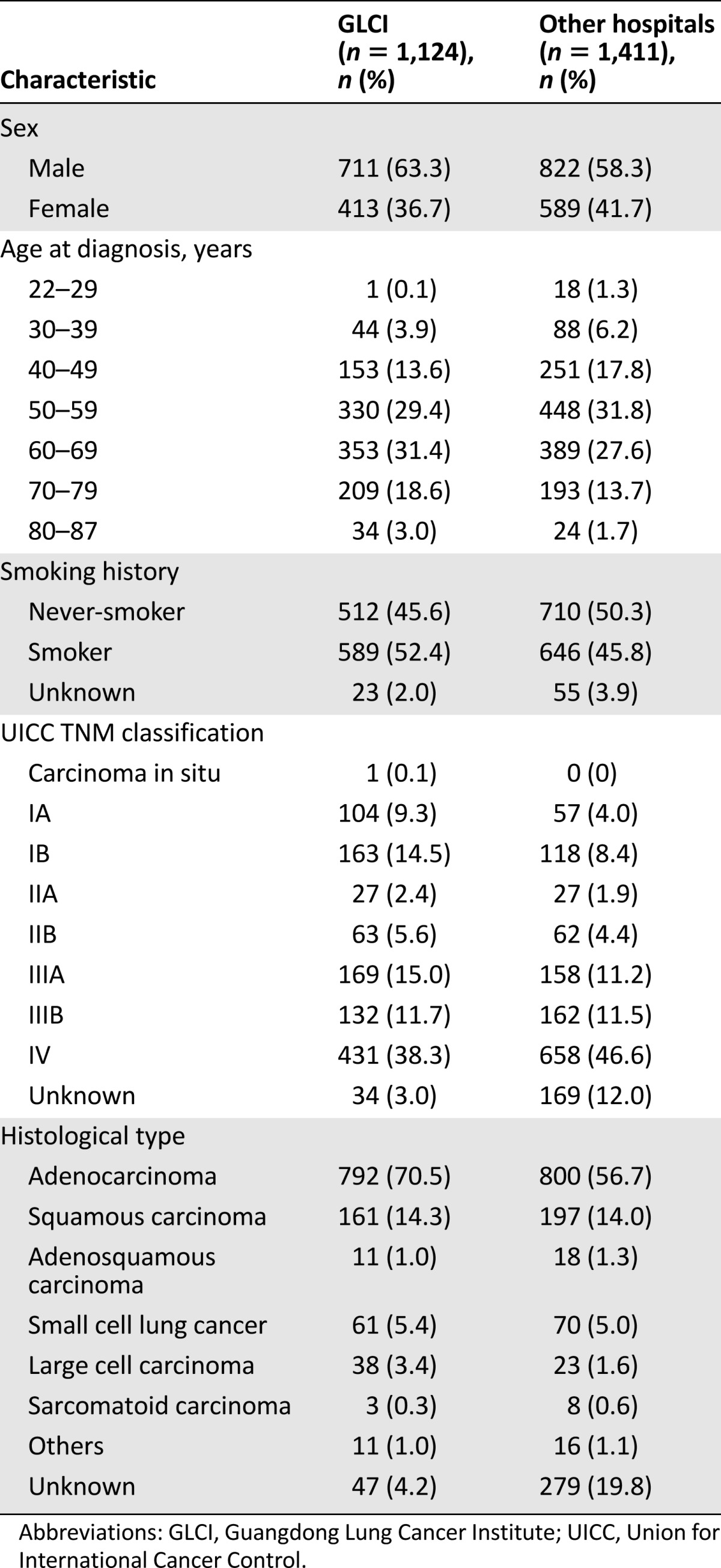

In total, 3,061 patients were included in the GLCI outpatient database (Fig. 1); 4.5% of patients (120 of 2,655) with suspected lung cancer refused any further diagnosis, examination, or treatment. An additional 2,535 outpatients with lung cancer were collected in this retrospective analysis. These patients were located across 29 provinces and 165 cities in China. The mean age was 58 years old. Female patients accounted for 39.5% (n = 1,002), and 48.2% of patients (n = 1222) were never-smokers. The most common histological diagnosis was adenocarcinoma (n = 1,592; 62.8%) followed by squamous cell carcinoma (n = 358; 14.1%). In total, 1,124 patients (44.3%) were initially diagnosed at GLCI, and 1,411 patients (55.7%) were initially diagnosed at other hospitals. The baseline clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1. Of the 2,535 non-GLCI patients, 19.1% (n = 484) with confirmed lung cancer diagnosis refused anticancer treatment at the time of initial diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Abbreviations: Jan, January; Oct, October.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of study patients

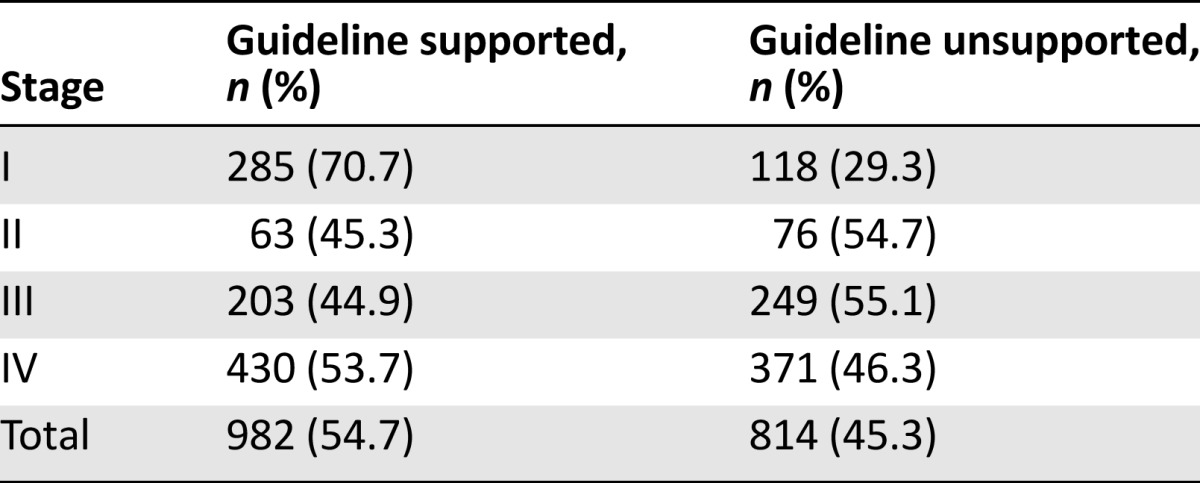

Treatment Disparities Based on Staging

The treatment disparity in this retrospective study was 45.3% (814 of 1,796 patients). Treatment disparities of patients with NSCLC by stage are summarized in Table 2. In total, 13.0% of patients (19 of 146) with stage IA NSCLC and 24.9% of patients (64 of 257) with stage IB NSCLC underwent perioperative chemotherapy except for patients who participated in clinical trials. Twenty-eight patients with stage II NSCLC did not receive perioperative chemotherapy. This meant that 20.6% of stage I patients (83 of 403) were overtreated and 20.1% of stage II patients (28 of 139) were undertreated.

Table 2.

Treatment disparities of patients with non-small cell lung cancer by stage

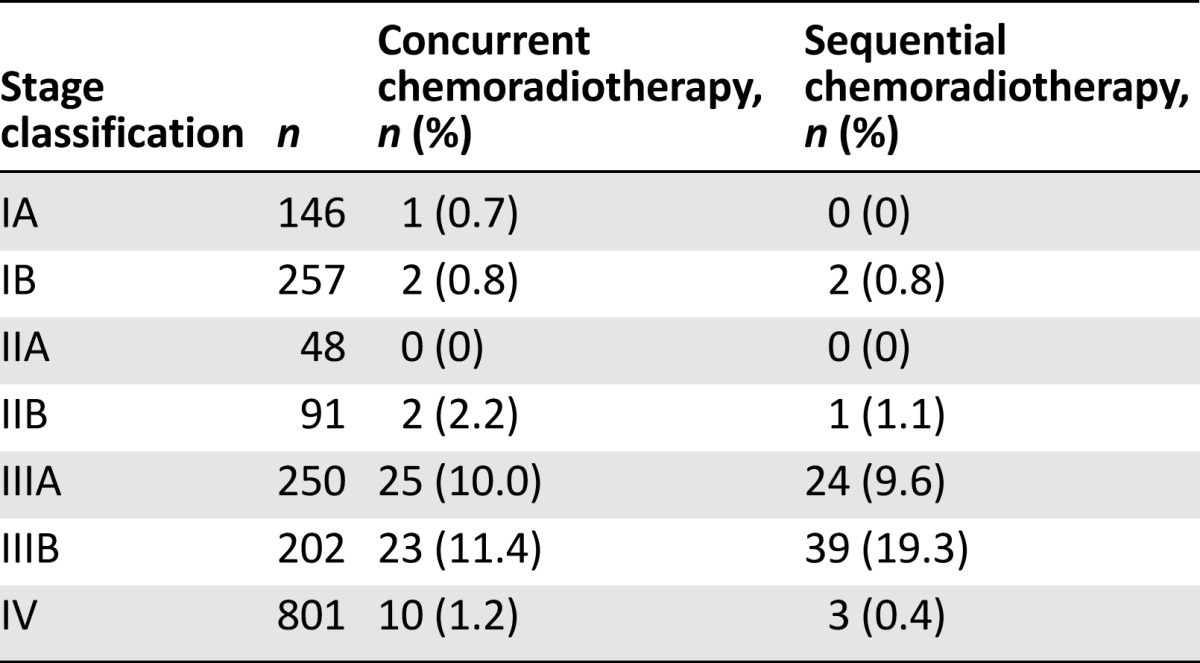

For stage IIIA and IIIB NSCLC, only 19.6% of stage IIIA patients (49 of 250) and 30.7% of stage IIIB patients (62 of 202) underwent the recommended combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Concurrent and sequential chemoradiotherapy according to stage classification

Treatment Disparities in Chemotherapy for Advanced NSCLC

A total of 1,038 patients with advanced NSCLC received first-line chemotherapy. The most commonly used regimen was a gemcitabine plus carboplatin doublet (n = 289; 27.8%,). Moreover, 7.3% (n = 76) of all patients with advanced NSCLC underwent nonrecommended regimens.

For advanced NSCLC, the greatest treatment disparity appeared in the second-line setting and beyond, where 45.7% of patients (205 of 449) received nonrecommended regimens as second-line chemotherapy, including platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, three-drug combination regimens, and nonstandard single-agent chemotherapy. In 128 patients with NSCLC receiving third-line chemotherapy, 49.2% (n = 63) received platinum-based doublets. In addition, 5.0% of patients with advanced NSCLC (40 of 801) frequently changed regimens despite nonprogression of disease.

Treatment Disparities in Molecularly Targeted Therapy for Advanced NSCLC

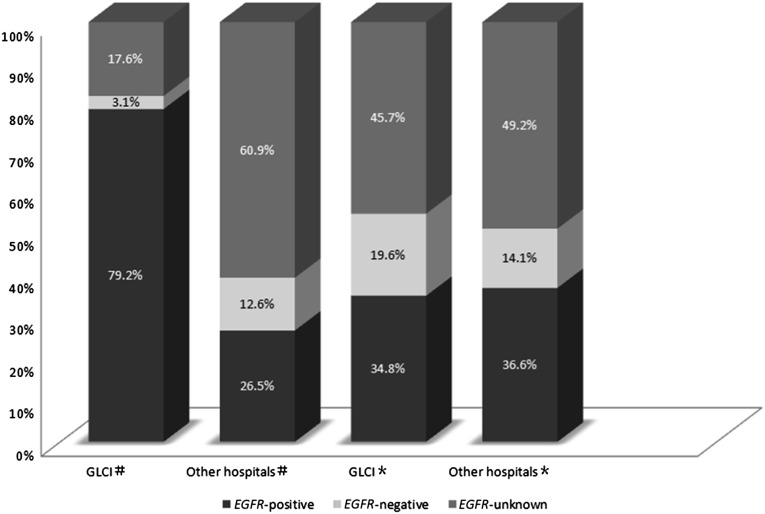

There were 310 patients with advanced NSCLC who received EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in the first-line setting; 53.5% (n = 166), 7.7% (n = 24), and 38.7% (n = 120) of these patients were positive, negative, or unknown, respectively, in terms of their EGFR mutation status. A total of 329 patients with advanced NSCLC received EGFR TKIs in the second-line setting. Only 35.9% (n = 118) of these patients had a positive EGFR mutation status. The EGFR mutant status in the first- and second-line settings is summarized in Figure 2. Compared with EGFR mutation-unknown or mutation-negative patients, EGFR-positive patients who received EGFR TKIs experienced significant prolongation of survival (HR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.63–0.99; p = .037).

Figure 2.

EGFR mutation status in first- and second-line setting of patients with advanced NSCLC. #, first-line setting; ∗, second-line setting.

Abbreviations: GLCI, Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Possible Factors Contributing to Treatment Disparities in NSCLC

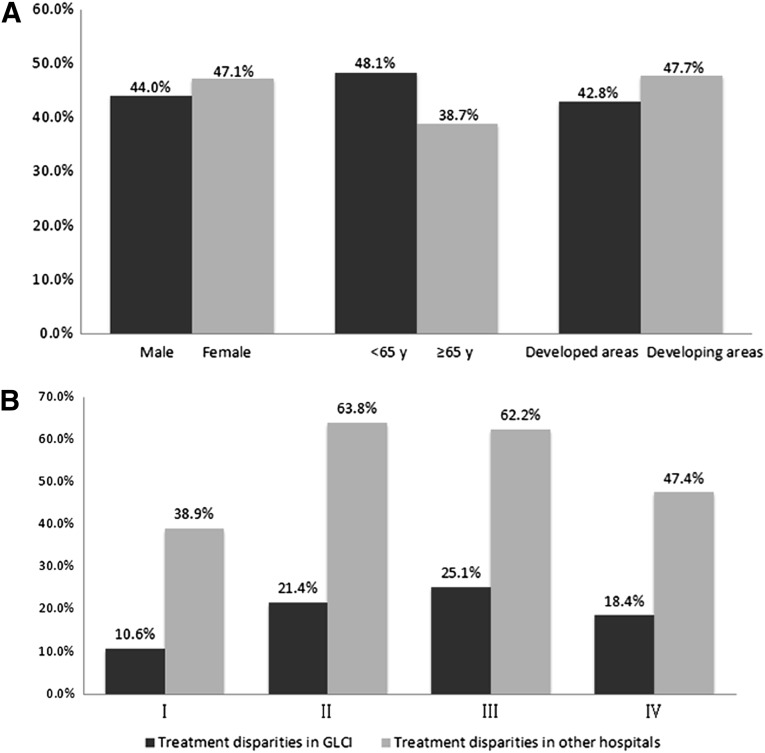

Treatment disparities were defined as treatments that were inconsistent with the guideline recommendations. The relationships between treatment disparities with regard to sex, age at diagnosis, and geographical distribution of patients are summarized in Figure 3A. The difference in treatment disparities was not statistically significant for sex (p = .203). However, treatment disparities were significantly larger for patients aged younger than 65 years compared with patients aged 65 years and older (p < .001). Patients from developed cities underwent more standard treatment compared with those from other regions (p = .046).

Figure 3.

NSCLC treatment disparities in the People’s Republic of China. (A): The relationships between treatment disparities by sex, age at diagnosis, and geographic distribution of patients. (B): Treatment disparities of patients with NSCLC by stage at GLCI and other hospitals.

Abbreviations: GLCI, Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; y, years old.

There were significant treatment disparities between GLCI and other hospitals; treatment compliance was 81.8% (883 of 1,080) and 49.4% (470 of 952) for GLCI and other hospitals (including university hospitals, tumor hospitals, and other), respectively, with guideline-recommended treatment (p < .001). Treatment disparities in patients with NSCLC by stage at GLCI and other hospitals are summarized in Figure 3B.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore disparities in the treatment of lung cancer in China. In this retrospective survey based on the outpatient database of GLCI in China, we found that significant treatment disparities of 45.3% persist in NSCLC. These disparities include overtreatment, treatment with nonrecommended chemotherapy regimens, a higher rate of surgical treatment of patients with stage IIIA NSCLC, and treatment of EGFR mutation-negative or -unknown patients with EGFR TKIs in the first-line setting. Although it is not expected that all NSCLC patients will be treated exactly according to the guidelines, the current adherence is too low. Most clinical trials for adjuvant chemotherapy after lung resection have shown benefits only in stage II and III NSCLC. However, 14.6% and 32.4% of patients with stages IA and IB NSCLC, respectively, in our survey underwent perioperative chemotherapy, whereas 20.1% of stage II patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. These treatment disparities are relatively severe. Data from a U.S. study showed a >90% rate of compliance with guideline-appropriate recommendations for adjuvant chemotherapy in NSCLC from 2006 to 2010 [9].

The observed disparity in surgical treatment for NSCLC in our study may be attributable to several patient-, physician-, and health system-related factors. Some social factors may relate to treatment disparity. For patients, poor health literacy and low educational attainment, lower income, and lack of health insurance contribute substantially to differences in lung cancer outcomes. Physicians’ treatment decisions also account for many of the observed treatment disparities. From structural and organizational points of view, a skilled and well-trained oncologist can help overcome the social factors that patients may bring to these treatment disparities, but a lack of cancer specialists has hampered cancer care in China [10]. Only ∼25,600 physicians are registered as oncologists in China [11], or less than 1 oncologist per 50,000 people. No board of oncology training exists in China to help graduate students who work in cancer hospitals to become oncologists. Recent surveys suggest that most oncologists have sound knowledge and awareness of advances in cancer treatment [12], but tumor boards involved in the multidisciplinary management of lung cancer are lacking at most tumor hospitals. Qualified oncologists are not evenly distributed across the country.

The application of radiotherapy as part of the regular treatment of lung cancer is surprising. Randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses have generally shown that concurrent chemoradiotherapy, despite being associated with increased acute toxicity, is a better strategy than sequential chemoradiotherapy [13–15]. However, only 19.6% of patients with stage IIIA NSCLC and 30.7% of patients with stage IIIB NSCLC in our study received combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy. More patients underwent sequential chemoradiotherapy than concurrent chemoradiotherapy. This finding may reflect poor access to radiotherapy facilities in some areas and a lack of specialist interest in lung cancer among clinical oncologists.

For advanced NSCLC, treatment disparities were observed mainly in the second-line setting. Our study showed that 45.7% of patients with NSCLC underwent nonrecommended regimens as second-line chemotherapy, and nearly half of the patients received platinum-based doublets as third-line chemotherapy. Docetaxel and pemetrexed are recommended as standard second-line chemotherapy for patients with disease progression after first-line chemotherapy [13, 16, 17]. The main objective of treatment of advanced NSCLC is to improve quality of life and prolong survival. Current data are insufficient to recommend the routine third-line use of cytotoxic drugs, and the best choice for such patients should be participation in a clinical trial or best supportive care. Our survey indicates that there was overtreatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.

The greatest changes and advances in NSCLC have been driven by molecularly targeted therapy guided by the patient’s molecular status. EGFR TKIs are recommended only for NSCLC patients with tumors harboring activating EGFR mutations in the first-line setting [18]. Despite this guideline, only 53.5% of patients who received EGFR TKIs had EGFR mutation-positive tumors during first-line treatment. However, the addition of novel target drugs to standard treatment for lung cancer subtypes has increased costs. Patients and their families may face staggering copayments and other shared costs. How to balance this disparity has become a new problem faced by policy makers.

In our survey, 1 in 5 patients (19.1%) with documented lung cancer refuse any active treatment at diagnosis. This ratio is too high. The primary reason is poverty, financial insecurity, and lack of medical insurance. In 2003, approximately 79% of rural residents were uninsured in China. Although China has established a universal medical insurance system in the past decade, patient out-of-pocket costs were 34.8% in 2011. This is a particular problem in advanced NSCLC, for which the average mean cost of all care in the final 3 months of life is $16,955 (in U.S. dollars), far exceeding the financial ability of most households [19]. To improve this situation, reducing social inequality by strengthening social safety nets, establishing minimum wages, and improving coverage of basic and health care insurance must become priorities.

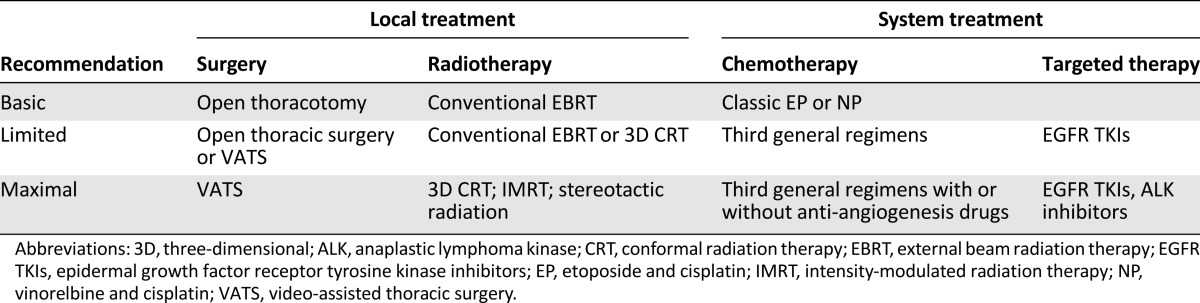

This study showed that GLCI had good compliance with guideline-guided treatment, whereas a compliance rate of only 49.4% was seen at other hospitals. The difference may be explained in part by economic development. GLCI is located in a developed area in China and has spent more than 10 years building its multidisciplinary team for lung cancer. Some other hospitals are located in developing areas or in underdeveloped areas and face barriers such as shortages of trained oncological physicians, lack of diagnostic and treatment capacity, and financial constraints. In light of these observations, it is important to develop new guidelines with recommendations based on resource classification (Table 4).

Table 4.

Recommendations based on resource classification

This registry-based study had several unique advantages. The survey was based on our outpatient database, which included continuous data over more than 8 years and a large sample size. In addition, the database contained 225 detailed characteristics of outpatients. The information on outpatients in the database was relatively comprehensive. Furthermore, the data were objective because all outpatient electronic data were compiled from questionnaires, which may have selection bias.

We acknowledge that our study had some limitations. First, this survey was a retrospective review, and the distribution of these patients was not balanced across China. Because 44.3% of patients were initially diagnosed at GLCI and underwent relatively standard treatments based on the clinical practice guidelines in GLCI, we may have overestimated the current status of treatment in patients with lung cancer in China. Second, the data regarding follow-up, patient preference, performance status, and comorbidities in the outpatient database were incomplete, and that influenced further analysis.

We believe that our study has important implications. Lung cancer treatment disparities are an issue not only of innate biological factors but also of modifiable characteristics of individual behavior and decision making as well as characteristics of the patient health system. With an emphasis on treatment disparities and opportunities for future research, guideline-recommended treatment is critical and requires coordination among different clinical specialties, multiple providers, and health care settings.

Conclusion

This retrospective survey based on 2004–2013 data demonstrates that the treatment of patients with lung cancer in China does not consistently meet the standard set by the national guidelines. Increased collaboration is needed among different areas in China to provide standardized treatment and palliative care to patients with lung cancer. China needs to establish consensus based on resource classifications (basic to maximal) to take into account the diversity of settings in China. Such a consensus will be difficult to achieve, but it offers an opportunity to ensure that all patients with lung cancer in China—regardless of socioeconomic and geographic barriers—are treated to the same basic standard of care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant 81272618 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. We thank the participants and the staff of GLCI for their contribution to this research.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related commentary, “The Yin-Yang of Guidelines and Disparity,” by Tony Mok, on page 1011 of this issue.

For Further Reading:Ting-Shou Chang, Kuang-Yung Huang, Chun-Ming Chang et al. The Association of Hospital Spending Intensity and Cancer Outcomes: A Population-Based Study in an Asian Country. The Oncologist 2014;19:990–998.

Implications for Practice:No large-scale national study has explored the association between hospital spending intensity and cancer outcomes. This large, nationwide study showed that patients with colorectal cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, hepatoma, lung cancer, or head and neck cancer who underwent treatment at hospitals with low spending intensity are at significantly higher risk of mortality than those treated at hospitals with high spending intensity.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Lu-Lu Yang, Xue-Ning Yang, Yi-Long Wu

Provision of study material or patients: Lu-Lu Yang, Xue-Ning Yang, Jin-Ji Yang, Zhen Wang, Hua-Jun Chen, Chong-Rui Xu, Yan-Yan He, Wen-Zhao Zhong, Yi-Long Wu

Collection and/or assembly of data: Lu-Lu Yang, Xue-Ning Yang, Hong-Hong Yan, Yi-Long Wu

Data analysis and interpretation: Lu-Lu Yang, Xu-Chao Zhang, Xue-Ning Yang, Jin-Ji Yang, Zhen Wang, Hua-Jun Chen, Hong-Hong Yan, Chong-Rui Xu, Ji-Lin Guan, Wen-Zhao Zhong, She-Juan An, Yi-Long Wu

Manuscript writing: Lu-Lu Yang, Xu-Chao Zhang, Yi-Long Wu

Final approval of manuscript: Lu-Lu Yang, Xu-Chao Zhang, Xue-Ning Yang, Jin-Ji Yang, Zhen Wang, Hua-Jun Chen, Hong-Hong Yan, Chong-Rui Xu, Ji-Lin Guan, Yan-Yan He, Wen-Zhao Zhong, She-Juan An, Yi-Long Wu

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cancer. Fact sheet no 297. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ Accessed September 23, 2012.

- 2.Jakobsen E, Palshof T, Osterlind K, et al. Data from a national lung cancer registry contributes to improve outcome and quality of surgery: Danish results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:348–352; discussion 352. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jernberg T, Johanson P, Held C, et al. Association between adoption of evidence-based treatment and survival for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011;305:1677–1684. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson AM, Hines RB, Johnson JA, III, et al. Treatment and survival disparities in lung cancer: The effect of social environment and place of residence. Lung Cancer. 2014;83:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhi XY, Wu YL, Bu H, et al. Chinese guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer (2011) J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:88–101. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feenstra C. Healthy people 2010. Mich Nurse. 2000;73:14–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler SB, Reeder-Hayes KE, Carey LA. Disparities in breast cancer treatment and outcomes: Biological, social, and health system determinants and opportunities for research. The Oncologist. 2013;18:986–993. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.World Health Organization. Health profiles - China. Available at http://hiip.wpro.who.int/portal/Countryprofiles/China/Healthprofiles/TabId/171/ArtMID/913/ArticleID/45/Default Accessed June 21, 2013.

- 11.China Statistics Yearbook, 2012. Available at http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2012/indexch.htm Accessed on August 05, 2013.

- 12.Kantar Health. Cancer treatment in China: Implications and opportunities for pharma in 2011 and beyond. Available at http://www.kantarhealth.com/docs/ebooks/pharmavoice-cancer-treatment-china-11.pdf Accessed August 5, 2013.

- 13.Fournel P, Robinet G, Thomas P, et al. Randomized phase III trial of sequential chemoradiotherapy compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Groupe Lyon-Saint-Etienne d’Oncologie Thoracique-Groupe Français de Pneumo-Cancérologie NPC 95-01 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5910–5917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran WJ, Jr, Paulus R, Langer CJ, et al. Sequential vs. concurrent chemoradiation for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Randomized phase III trial RTOG 9410. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1452–1460. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zatloukal P, Petruzelka L, Zemanova M, et al. Concurrent versus sequential chemoradiotherapy with cisplatin and vinorelbine in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized study. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;379:805–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]