Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a clonal stem cell disorder of hematopoietic cells. Gastrointestinal complications of PNH are rare and mostly related with intravascular thrombosis or intramural hematoma.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We describe a case of a man with PNH complicated by intramural duodenal hematoma initially treated with supportive care. Three months after his first admission; he was admitted to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. He had undergone to surgery because of duodenal obstruction was treated with duodenojejunal by-pass surgery.

DISCUSSION

Patients were healed from gastrointestinal complications could suffer from gastrointestinal strictures, which cause wide spread symptoms ranging from chronic abdominal pain and anorexia to intestinal obstruction.

CONCLUSION

We report a rare intestinal obstruction case caused by stricture at the level of ligamentum Treitz with PNH. The possibility simply has to be borne in mind that strictures can be occurring at hematoma, ischemia or inflammation site of gastrointestinal tract.

Keywords: Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, Intestinal obstruction

1. Introduction

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a clonal stem cell disorder of hematopoietic cells. The disorder of cell membrane protein synthesis due to somatic mutation of PIG-A gene make blood cells sensitive to normal complement activation results in hemolytic anemia.1 Clinical reflections include intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, marrow aplasia, and venous thrombi.2 PNH is not often associated with gastrointestinal complications. Budd-Chiari syndrome is the frequent thrombotic complication in the abdomen and intestinal ischemia is an important clinical implication of PNH.3

We describe a case of PNH complicated by intramural duodenal hematoma initially treated with supportive care, and delayed duodenal obstruction treated with surgery.

2. Presentation of case

A 49-year-old man was admitted to the internal medicine department with fatigue, anorexia and hemoglobinuria. He had only diabetes mellitus in his medical history. He was diagnosed with PNH presented with duodenal obstruction symptoms. Androgen and Sellium treatment was commenced for PNH.

Three months after the diagnosis, he was admitted to the emergency department because of fatigue, anorexia and nausea. Abdominal tomography revealed a mural hematoma in the distal part of duodenum. A duodenal mural hematoma did not caused complete obstruction of the duodenal lumen was found at the esophagogastroduodenoscopy. After conservative therapy – nil orally and intravenous fluids – patient recovered without any problem. Treatment of PNH was changed to ecelizumab.

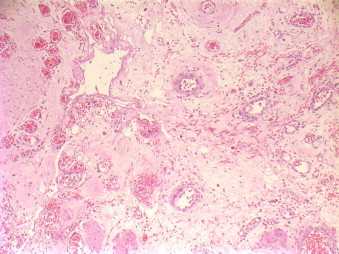

Again, eight months after the diagnosis; he was admitted to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. He had had these progressive complaints for 3 days. Physical examination at the last administration was unremarkable except decreased bowel sounds. Laboratory investigations showed leucocytoses of 11,800/μL, slightly elevated with total bilirubin of 3.2 mg/dL and direct bilirubin of 1.4 mg/dL and no abnormality in prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time. Abdominal tomography revealed total occlusion at duoudenojejunal junction and severe dilatation of stomach and duodenum (Fig. 1a). Plain radiography of abdomen with oral water-soluble contrast revealed obstruction of distal duodenum not allowing the passage of contrast (Fig. 1b). An emergent laparotomy was performed. At exploration, duodenal obstruction was found at the level of ligamentum Treitz. The cause of the obstruction was complete stricture of duodenum (Fig. 2). Duodenojejunal by-pass was achieved by side-to-side duodenojejunal anastomosis. Biopsy was taken from the stricture site before anastomosis. Patient was discharged from hospital on the fifth postoperative day without any complications. Histopathological examination of biopsy taken from stricture site revealed granulation tissue with a number of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, composed of dilated, congested vascular structures, and inflammatory cells (Fig. 3). Granulation tissue, composed of dilated, congested vascular structures, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, edema and inflammatory cells were seen (hematoxylin–eosin, 100×)

Fig. 1.

Total occlusion at duoudenojejunal junction and severe dilatation of stomach and duodenum at abdominal tomography (a), obstruction of distal duodenum did not allow the passage of contrast (b).

Fig. 2.

Complete stricture of duodenum caused obstruction.

Fig. 3.

Granulation tissue, composed of dilated, congested vascular structures, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, edema and inflammatory cells were seen (hematoxylin–eosin, 100×).

3. Discussion

PNH is an acquired disease characterized by attacks of intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria. It can lead to profound anemia, thrombocytopenia and leucopenia, and is often complicated by venous thrombosis.4 Gastrointestinal involvement of PNH is thought to be related to occult mesenteric thromboses and transient intestinal ischemia. Since Crosby5 reported that 54% of patients were found to have hepatic or portal thrombi, there have been four reported cases of intestinal ischemia treated successfully with surgical intervention.6–10

Duodenal hematoma is rare, generally occurring after abdominal trauma or endoscopic biopsy or in association with peptic ulcer disease.11 Duodenal hematoma usually resolves spontaneously within 7–10 days; thus, conservative treatment is recommended instead of surgical treatment as first line therapy.12 Surgery or percutaneous drainage should be reserved for patients with persistent obstruction or expanding hematomas.11,12 As to our patient, duodenal hematoma occurred rather due to PNH and other reasons such as trauma or endoscopy. Duodenal hematoma caused duodenal obstruction symptom but he recovered quickly with conservative treatment. Even if he was under androgen treatment; pancytopenia was consisted and spontaneous duodenal hematoma occurred. Thus, treatment of PNH was changed to ecelizumab after this incident.

Small bowel obstructions are most commonly caused by adhesions, hernias, neoplasms, ischemia, or inflammatory strictures, which are usually caused by extraluminal adhesions due to postoperative inflammatory changes.13 We found the obstruction at the localization of the hematoma at the level of ligamentum Treitz. Our patient had no clinical or pathologic evidence of acute or chronic inflammatory bowel disease. There have been reports of intestinal ischemia because of PNH6–9; but our patient had no history of acute or chronic intestinal ischemia. We can only estimate that stricture was due to excessive healing process after hematoma because there was no proven reason for stricture formation. As a matter fact, it has been shown that the hematoma may produce a cicatrizing inflammatory reaction capable of permanently scarring intestinal wall.14 Late strictures are rare; but few reports recorded persisting deformity and stricture.15 Adams et al.10 reported electron microscopic findings of an antemortem intestinal ischemia case. The electron microscopy findings were capillaries with coarsely granular plasma and fibrin plugs that nearly occluded the lumen. Additionally, lysosomal inclusion bodies bore a resemblance to siderosomes (iron-laden by-products of red blood cell breakdown) and they were seen within hypertrophied endothelial cells of affected capillaries, as well as throughout the plasma.

4. Conclusion

We report a rare intestinal obstruction case caused by stricture at the level of ligamentum Treitz with PNH. The possibility simply has to be borne in mind that strictures can be occurring at hematoma, ischemia or inflammation site of gastrointestinal tract.

Conflict of interest

All authors disclose that there are no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) the work.

Funding

There are no sources of funding should be declared.

Ethical approval

This case report does not require ethical approval. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

TT conceptualized this manuscript, collected data and wrote the manuscript. YE assisted in writing this manuscript and checked it for intellectual content. MK assisted with data collection and analysis of the manuscript. FK assisted with data collection, writing and analysis of the intellectual content. MT assisted with data collection, writing and analysis of the intellectual content. GM assisted with analysis and the critical review of the intellectual content.

Key learning points.

Gastrointestinal complications of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

-

•

Intravascular coagulation.

-

•

Intestinal wall hematoma.

-

•

Obstruction due to stricture.

References

- 1.Takeda J., Miyata T., Kawagoe K.Iida, Y Endo Y., Fujita T. Deficiency of the GPI anchor caused by a somatic mutation of the PIG-A gene in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Cell. 1993;73:703–711. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90250-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosse W.F. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria as a molecular disease. Medicine. 1997;76:63–85. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199703000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valla D., Dhumeaux D., Babany G., Hillon P., Rueff B., Rochant H. Hepatic vein thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. A spectrum from asymptomatic occlusion of hepatic venules to fatal Budd-Chiari syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:569–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee G.R., Foerster J., Lukens J., Paraskevas F., Greer J.P., Rodgers G.M., editors. Wintrobe's clinical hematology. 10th ed. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1999. pp. 1018–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crosby W. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a classic description by Paul Strubing in 1882, and a bibliography of the disease. Blood. 1951;6:270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum S.F., Gardner F.H. Intestinal infarction in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:1137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doukas M., DiLorenzo P., Mohler D. Intestinal infarction caused by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Am J Hematol. 1984;16:75–81. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830160110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson L.M., Johnstone J.M., Preston F.E. Microvascular thrombosis of the bowel in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:930–931. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.8.930-c. [letter] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zapata R., Mella J., Rollan A: Intestinal ischemia complicating paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:184–186. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams T., Fleischer D., Marino G., Rusnock E., Li L. Gastrointestinal involvement in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: first report of electron microscopic findings. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(1):58–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1013207318697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas M.A., Collins J.M., Olden K.W. Spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma: imaging findings and outcome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1389–1394. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borsaru A.D., Nandurkar D. Intramural duodenal haematoma presenting as a complication after endoscopic biopsy. Australas Radiol. 2007;51:378–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2007.01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markogiannakis H., Messaris E., Dardamanis D.D., Pararas N., Tzertzemelis D., Giannopoulos P. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:432–437. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jewett T.C., Jr., Caldarola V., Karp M.P., Allen J.E., Cooney D.R. Intramural hematoma of the duodenum. Arch Surg. 1988;231:54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400250064011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd D.R., Taybi H., King H. Intramural haematoma of the small bowel. Arch Surg. 1964;89:527. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1964.01320030117020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]