Abstract

Objectives:

Milk consumption has long been recognized for its important role in bone health, but its role in the progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA) is unclear. We examine the prospective association of milk consumption with radiographic progression of knee OA.

Methods:

In the Osteoarthritis Initiative, 2,148 participants (3,064 knees) with radiographic knee OA and having dietary data at baseline were followed up to 12, 24, 36 and 48 months. The milk consumption was assessed with a Block Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire completed at baseline. To evaluate progression of OA, we used quantitative joint space width (JSW) between the medial femur and tibia of the knee based on plain radiographs. The multivariate linear models for repeated measures were used to test the independent association between milk intake and the decrease in JSW over time, while adjusting for baseline disease severity, body mass index, dietary factors and other potential confounders.

Results:

We observed a significant dose-response relationship between baseline milk intake and adjusted mean decrease of JSW in women (p trend=0.014). With increasing levels of milk intake (none, ≤3, 4-6, and ≥7 glasses/week), the mean decreases of JSW were 0.38mm, 0.29mm, 0.29mm and 0.26mm respectively. In men, we observed no significant association between milk consumption and the decreases of JSW.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that frequent milk consumption may be associated with reduced OA progression in women. Replication of these novel findings in other prospective studies demonstrating the increase in milk consumption leads to delay in knee OA progression are needed.

Keywords: milk consumption, diet, osteoarthritis progression, joint space width

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), a slowly progressing disease characterized by pain, deformity, and loss of function, is the major cause physical disability in older people. (1) (2) Nearly 27 million have clinical osteoarthritis in the United States.(2) With the aging of the population, the health care burden from OA is expected to increase dramatically during the next few decades.(3) However, little is known about the course of disability over time in patients with OA. It is, therefore, of great importance to identify modifiable risk factors for OA progression. Over the past few decades, many observational studies have examined risk factors for the incidence and progression of knee OA. Several risk factors (i.e., obesity, joint injury, and certain sports) have been found to be strongly associated with an increased risk for incident knee OA. (4, 5) However, findings on risk factors for OA progression have been inconclusive. There are scarce data on the possible role of dietary factors, though low intake of antioxidant vitamins (A, C, E) and vitamin D may be associated with increased risk of progression of knee OA (6-8).

Milk is an excellent source of vitamins and minerals, dairy calcium and protein. It has long been recognized for its important role in bone health. (9-11) The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that milk and other dairy products should be consumed daily as part of a balanced diet. (12) Our interest in the role of milk consumption related to osteoarthritis was triggered by two small studies: an earlier report of Colker et al (13) and a cross-sectional study in Turkey.(14) Based upon the protective role of bone health on OA progression and these previous preliminary findings, we hypothesized that milk consumption may prevent OA progression. We therefore examined the prospective association between milk consumption and progression of knee OA using publicly available data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI).

Patients and Methods

Subjects

OAI was launched in 2002 by the National Institute of Health (NIH) to develop resources for the identification of new biomarkers and treatment targets for knee OA. The objective of the OAI was to pool public and private scientific expertise and funding to collect, analyze, and make widely available the largest research resource to date of clinical data, radiologic information, and biospecimens from those at risk for or with knee OA. The OAI began enrolling people aged 45 through 79 years in 2004 and followed them annually for the development or progression of OA. The clinical sites involved were located in Baltimore, MD; Columbus, OH; Pittsburgh, PA; and Pawtucket, RI. OAI has been a longitudinal study of 4,796 subjects with either established knee OA or significant risk factors for the development of knee OA followed over an 8-year period. The follow-up rate was >90% over the first 48 months. The detailed OAI protocol can be found elsewhere. (15)

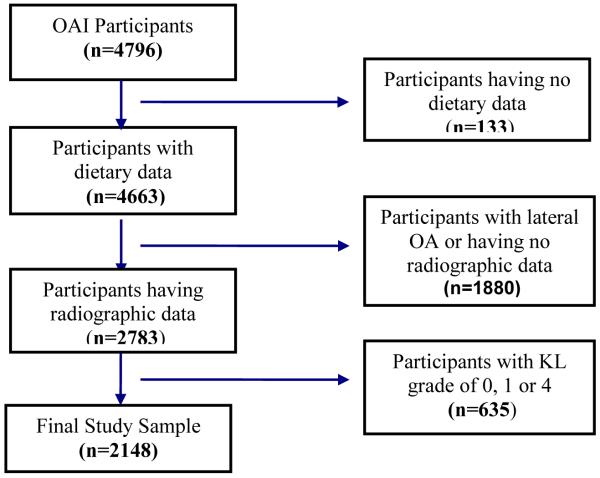

For the current study, we included individuals with medial radiographic knee OA in at least one knee based on OAI central X-ray reading at baseline. We excluded knees with severe radiographic OA defined as the baseline Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grade of 4 or those with primarily lateral joint space narrowing (JSN), and knees in which the difference of rim distance (from tibial plateau to tibial rim closest to femoral condyle) between any follow-up visit and the baseline visit were ≥2mm to minimize possible effects of knee positioning changes on measurement error of JSW. The 2,148 participants (3,064 knees) with KL grade of 2 or 3 and having dietary data at baseline constituted the study sample (figure 1). Follow-up at 12, 24, 36 and 48 months were included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Osteoarthritis Initiative participants included in the current study at baseline

Radiographic progression of OA

In OAI, current radiographic assessment techniques on plain radiographs involved both quantitative and semi-quantitative assessment of JSN. A quantitative approach was used to provide a precise measure of joint space width (JSW) in millimeters between the adjacent bones of the knee. (16, 17) Multiple JSWs were measured at fixed locations along the joint in medial compartment, denoted as JSW(x), at 0.025 intervals for x = 0.15 - 0.30. The reproducibility of this technique and the responsiveness to change have been documented elsewhere,(16) (18) including one study using OAI data which demonstrated a responsiveness that compared favorably to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).(18) We used medial JSW at x=0.25 with the best responsiveness of change to quantify the progression of OA. (18) We define the repeated measures of the changes of JSW from baseline to 12, 24, 36 and 48 months as the outcome variable. To account for changes in beam angle and alignment at each visit which introduces measurement error in serial JSW measurements, we also adjusted for changes of the beam angles and rim distances (from tibial plateau to tibial rim closest to femoral condyle between follow-up visits and baseline). For the semi-quantitative approach, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International grade (OARSI grade: 0=no JSN, 1=definite JSN to 3=severe JSN) has been widely used to measure progression of OA.(19) For these analyses, we used the publically available quantitative JSW measurements (version 12/08/2011, http://oai.epi-ucsf.org) and the semi-quantitative JSN readings (kXR_SQ_BU, version 11/07/2011, http://oai.epi-ucsf.org).

Assessment of milk consumption

Usual dietary intakes of foods and nutrients including milk consumption were assessed at baseline with a Block Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) including 60 food items in OAI. (20) The participants were asked how often they drank milk (any kind) in the past 12 months (coded as: never, a few times per year, once per month, 2-3 times per month, once per week, twice per week, 3-4 times per week, 5-6 times per week, and every day) and how many glasses each time. In this analysis, we grouped milk consumption into 4 categories including none, the highest and two middle categories (none, ≤3, 4-6, and ≥7 glasses/week). This brief FFQ has been validated against three four-day records in a group of middle-aged women, and against two seven-day records in a group of older men. The absolute value of macronutrients estimated by the reduced questionnaire was a slightly lower than food-record estimates, but most micronutrients were not underestimated. (20, 21)

Information on covariates

Baseline demographic and socioeconomic factors include race/ethnicity, age, sex, marital status, education level, employment status, annual income and social support. Individuals were classified as African American, white, or other racial/ethnic group based on self report. Education level was categorized as high school or less, college and above college. General clinical parameters include current smoking, depression defined as the CES-D 20 item scale >16 (22), history of traumatic knee injury and knee surgery, self-reported gout, baseline disease severity (KL grade), alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, weight change, NSAIDs use, other dairy products intake (yogurt, cheese), and other dietary factors (quartiles) (total calories, fat, grain, vegetable and fruit, meat, fish, soft drink, dietary and supplement vitamin A, C, D, E). BMI defined as the individual's body mass divided by the square of his or her height (kg/m2) was categorized into <25.0, 25.0-29.9, and ≥30 kg/m2 using World Health Organization criterion. Physical activity was assessed by using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), an established questionnaire for measuring physical activity in older individuals that has also been validated in younger subjects.(23, 24). Alcohol consumption was assessed at baseline including separate items for beer, wine, and liquor in OAI (none or less than 5 grams /day, 5-10 grams/day, >10 grams/day). We also adjusted for changes of the beam angles and rim distances (from tibial plateau to tibial rim closest to femoral condyle between follow-up visits and baseline) which indicate knee-positioning consistency for x-ray exam.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was to assess the influence of milk consumption on the decrease in JSW over the study period. The primary outcomes were repeated measures of the JSW decreases from baseline to 12, 24, 36 and 48 months respectively. The milk intake was analyzed as a categorical variable (none, ≤3, 4-6, and ≥7 glasses/week) as well as a continuous variable. The initial analyses were unadjusted comparisons of the decreases of JSW among levels of milk intake at each time point using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Gender specific differences in results were noted, therefore separate multivariate models for repeated measures by men and women were used to test the independent association between milk intake and the decrease in JSW over time, while adjusting for baseline disease severity, BMI, dietary factors and other potential confounding factors described above. Due to the hierarchical structure of the data (three levels: participant- knee - measures over time), we used linear mixed models to account for within subject correlation and the correlation of repeated measures in knee level. To assess the possible differential effect of milk intake across the follow-up time points, we included milk by follow-up time interaction in the model. The final covariance models were evaluated using Akaike's information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

In secondary analyses, we evaluated the associations between other dairy products (yogurt, cheese) consumption and JSW changes after controlling for milk consumption and other covariates using separate models. Furthermore, we developed additional models to evaluate whether or not dietary and supplemental calcium intake mediated the association of milk consumption with JSW change. We also included interactions between milk intake and important covariates (race, smoking, obesity, physical activity, K-L grade, vitamin D and calcium intake) in the model to evaluate potential effect modifications.

To test the robustness of our results, we also used the first full grade increase of the OARSI JSN grade as the endpoint for OA progression. We developed a Cox proportional hazards model to assess independent association between milk intake and the JSN score change after controlling for other covariates. For each participant, the time of follow-up was calculated from the baseline date to the date of the first increase of JSN grade, death, or end of the study, whichever came first. The discrete likelihood method was used for ties of the failure times in the models. We used a robust sandwich covariance estimate to account for the intraclass dependence within individual patients. (25) Participants who indicated no milk intake in the past year were chosen as the reference group for all analyses. Adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were used to evaluate the strength of the associations. The proportional hazard assumption was tested based on the smoothed plots of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals.(26) Data analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

In this study, we studied 2,148 participants from OAI having a total of 3,087 eligible knees. The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in table 1 according to levels of milk intake in men and women. Compared to no milk intake, high milk drinkers were more likely to be non-Hispanic white and non-smokers. In women, high milk drinkers were also more likely to be older and had more severe OA at baseline. Over the study period, 16.8% participants were loss to follow up. We did not observed significant differences in baseline characteristics between loss to follow up and non-loss to follow up participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with osteoarthritis according to milk intake

| Men (n=888) Milk intake, glasses/ week |

Women (n=1260) Milk intake, glasses/ week |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total N=2148 |

None n= 133 |

≤3 n=342 |

4-6 n=173 |

≥7 n=240 |

P value | None n= 238 |

≤3 n=473 |

4-6 n=246 |

≥7 n=303 |

P value |

| Age in years, mean (SD) |

62.4(9.0) | 62.5(9.7) | 61.7(8.9) | 63.3(9.4) | 62.6(9.5) | 0.372 | 61.3(8.8) | 61.9(8.4) | 62.8(9.1) | 64.0(8.5) | 0.001 |

| Race, % | |||||||||||

| Non-hisp White | 76.1 | 66.2 | 82.2 | 85.6 | 87.5 | <0.001 | 59.2 | 69.1 | 74.4 | 84.5 | <0.001 |

| Non-hisp Black | 20.7 | 27.8 | 14.9 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 37.8 | 29.6 | 19.9 | 11.2 | ||

| Others | 3.2 | 6.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 5.7 | 4.3 | ||

| Education, % | |||||||||||

| ≤high school | 18.4 | 12.9 | 15.5 | 13.3 | 14.6 | 0.700 | 22.3 | 21.8 | 21.1 | 19.5 | 0.128 |

| College | 45.9 | 44.7 | 42.4 | 44.5 | 40.4 | 44.5 | 47.4 | 47.2 | 53.5 | ||

| Above college | 35.7 | 42.4 | 42.1 | 42.2 | 45.0 | 33.2 | 30.9 | 31.7 | 27.1 | ||

| HH Income, % | |||||||||||

| <25k | 15.2 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 0.562 | 21.1 | 17.0 | 21.8 | 20.6 | 0.252 |

| 25k-49k | 27.9 | 25.6 | 23.1 | 19.1 | 20.9 | 27.2 | 35.3 | 27.1 | 34.8 | ||

| 50k-99k | 36.0 | 34.9 | 40.1 | 38.7 | 45.8 | 34.3 | 33.3 | 30.6 | 32.3 | ||

| 100k+ | 21.0 | 31.0 | 28.6 | 31.6 | 23.6 | 17.4 | 14.5 | 20.5 | 12.4 | ||

| Married, % | 65.1 | 79.7 | 79.2 | 80.9 | 78.3 | 0.821 | 49.8 | 55.2 | 56.3 | 57.4 | 0.098 |

| Employed, % | 58.2 | 66.9 | 64.0 | 60.1 | 62.5 | 0.346 | 58.0 | 55.4 | 52.4 | 52.5 | 0.158 |

| Depressed, % | 8.8 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 0.635 | 8.4 | 12.9 | 9.8 | 7.6 | 0.273 |

| Smoke, % | |||||||||||

| Never | 54.1 | 48.1 | 44.5 | 48.6 | 58.3 | 0.010 | 56.3 | 54.6 | 59.4 | 60.4 | <0.001 |

| Current | 6.4 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 5.0 | 10.5 | 7.8 | 2.4 | 3.3 | ||

| Past | 39.6 | 43.6 | 49.1 | 43.4 | 36.7 | 33.2 | 37.6 | 38.2 | 36.3 | ||

| Alcohol, g/d | |||||||||||

| 0-<5 | 53.9 | 54.1 | 54.1 | 51.5 | 55.4 | 0.600 | 70.2 | 77.4 | 71.5 | 76.2 | 0.154 |

| 5-<10 | 11.2 | 7.5 | 11.1 | 13.9 | 11.3 | 10.5 | 8.9 | 11.8 | 12.2 | ||

| 10+ | 34.9 | 38.4 | 34.8 | 34.7 | 33.3 | 19.3 | 13.7 | 16.7 | 11.6 | ||

| PASE a, mean (SD) | 157.5(82.9) | 168.1(81.3) | 173.7(92.3) | 160.9(75.9) | 186.6(90.6) | 0.024 | 151.3(82.6) | 141.7(72.9) | 146.5(75.0) | 146.7(73.9) | 0.444 |

| BMI b (kg/m2), % | |||||||||||

| <25 | 15.7 | 12.8 | 9.4 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 0.048 | 23.1 | 15.6 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 0.657 |

| 25-29 | 38.4 | 41.4 | 43.9 | 52.6 | 48.3 | 31.5 | 33.0 | 27.3 | 36.3 | ||

| 30+ | 45.9 | 45.9 | 46.8 | 33.0 | 39.2 | 45.4 | 51.4 | 54.1 | 42.9 | ||

| Gout, % | 6.1 | 5.4 | 7.2 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 0.335 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.870 |

| K-L grade c | |||||||||||

| (index knee), % | |||||||||||

| 2 | 56.9 | 57.9 | 58.2 | 54.9 | 55.8 | 0.527 | 73.5 | 68.3 | 63.8 | 67.3 | 0.101 |

| 3 | 43.1 | 42.1 | 41.8 | 45.1 | 44.1 | 26.5 | 31.7 | 36.2 | 32.7 | ||

| NSAIDs d use, % | 22.0 | 15.4 | 24.4 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 0.828 | 18.0 | 23.6 | 27.4 | 22.1 | 0.262 |

| Dietary/Supplement Vitamin A,1000 IU/ d, mean (SD) |

14.0(10.0) | 12.2(9.0) | 12.7(11.0) | 13.0(7.8) | 14.7(10.7) | 0.012 | 13.1(11.6) | 13.5(9.6) | 14.7(9.1) | 17.2(9.5) | <0.001 |

| Dietary/Supplement Vitamin C, mg/ d, mean (SD) |

393.8(443.4) | 298.5(393.3) | 361.2(444.3) | 411.9(424.5) | 373.7(356.7) | 0.102 | 387.2(453.6) | 389.1(448.5) | 428.3(495.8) | 461.0(466.4) | 0.026 |

| Dietary/Supplement Vitamin E e, mg/ d, mean (SD) |

115.2(168.7) | 66.3(106.7) | 107.6(205.8) | 111.0(135.7) | 96.2(132.8) | 0.324 | 114.2(164.2) | 122.3(166.4) | 126.6(171.3) | 142.9(185.5) | 0.046 |

| Dietary/Supplement Vitamin D, IU/ d, mean (SD) |

364.4(247.0) | 277.1(214.0) | 298.5(228.6) | 367.2(243.8) | 450.6(248.1) | <0.001 | 358.0(250.2 | 357.1(229.1) | 396.1(231.0) | 557.3(258.6) | <0.001 |

| Dietary Calcium, mg/d, mean (SD) |

673.0(352.7) | 508.2(224.7) | 517.4(210.9) | 722.5(243.9) | 1089(371.5) | <0.001 | 437.7(200.1) | 487.3(196.0) | 676.2(222.9) | 1028(364.2) | <0.001 |

| Supplement Calcium, mg/d, mean (SD) |

468.1(472.9) | 205.5(348.2) | 238.0(367.3) | 263.0(376.9) | 251.1(361.0) | 0.252 | 617.8(493.1) | 585.5(470.8) | 633.6(466.9) | 695.5(470.2) | 0.010 |

| Total fat, g/d, mean (SD) |

55.4(27.5) | 60.0(29.4) | 57.1(23.5) | 62.4(30.3) | 72.0(31.7) | <0.001 | 47.6(26.1) | 48.4(24.4) | 52.4(23.9) | 53.3(27.3) | 0.001 |

| Total calories (Kcal/d), mean (SD) |

1422(588) | 1523(638) | 1418(526) | 1579(591) | 1906(650) | <0.001 | 1187(532) | 1210(507) | 1344(480) | 1487(550) | <0.001 |

| Total grain, servings/d, mean (SD) |

3.2(1.8) | 3.5(2.0) | 3.2(1.8) | 3.9(2.1) | 4.3(2.0) | <0.001 | 2.4(1.6) | 2.7(1.5) | 3.1(1.4) | 3.4(1.7) | <0.001 |

| Vegetable/ Fruit, servings/d, mean (SD) |

4.8(2.8) | 4.4(2.5) | 4.4(3.0) | 4.4(2.2) | 5.1(3.2) | 0.010 | 4.5(2.8) | 4.6(2.6) | 5.2(2.6) | 5.7(2.9) | <0.001 |

| Meat, servings/d, mean (SD) |

1.4(1.2) | 2.1(1.2) | 2.0(1.1) | 2.0(1.2) | 2.2(1.2) | 0.227 | 1.6(1.0) | 1.6(1.0) | 1.7(0.9) | 1.7(0.9) | 0.138 |

| Fish, servings/d, mean (SD) |

1.8(1.1) | 1.3(1.3) | 1.3(1.1) | 1.4(1.0) | 1.4(1.3) | 0.210 | 1.4(1.2) | 1.3(1.2) | 1.4(1.1) | 1.6(1.2) | 0.011 |

| Soft drink, glass/week, mean (SD) |

1.7(4.2) | 2.1(4.0) | 1.9(3.9) | 1.3(2.7) | 2.8(5.5) | 0.106 | 2.1(6.0) | 1.7(4.2) | 1.2(3.1) | 1.1(2.7) | 0.002 |

Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) score.

Body mass index.

Kellgren-Lawrence Scale.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including Aspirin, Ibuprofen, etc) use for joint pain or arthritis in past 30 days.

alpha tocopherol equivalents (alpha-TE).

Results of multivariable analyses are shown in table 2 in men and women. We observed a significant dose-response relationship between milk intake and adjusted mean decreases of JSW in women (p trend=0.014) after controlling for the covariates listed above. With increasing levels of milk intake, the mean decreases of JSW were 0.38mm, 0.29mm, 0.29mm and 0.26mm respectively. When we included milk intake as a continuous variable, a 10 glasses increase in milk intake per week was associated with a decrease of 0.06 mm JSW change over 48 months (p=0.020). By contrast in men, we did not observe a significant inverse association of milk intake with JSW change. We did not observe the significant interactions between milk consumption and follow-up time in men and women (p for interaction was 0.372 in women and 0.735 in men). Additional adjustment for alcohol consumption and a history of gout in the above models did not change the results. Inconsistent with milk consumption, ≥7 servings/week cheese consumption was associated with increased JSW decrease compared to no cheese intake in women (p=0.003), while combined dairy products and yogurt consumption were not associated with JSW change after adjusting for milk consumption and other covariates (data were not shown).

Table 2.

Adjusted mean decrease (SE) of Joint Space Width (JSW) during follow-up by milk intake

| Glasses /week |

Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | △JSW, mm* | P value | P trend |

N | △JSW, mm* |

P value | P trend | |

| None | 133 | 0.32(0.05) | Referent | 238 | 0.380.04) | Referent | ||

| ≤3 | 342 | 0.35(0.04) | 0.611 | 473 | 0.29(0.03) | 0.013 | ||

| 4-6 | 173 | 0.41(0.04) | 0.130 | 246 | 0.29(0.03) | 0.025 | ||

| ≥7 | 240 | 0.33(0.04) | 0.820 | 0.618 | 303 | 0.26(0.03) | 0.006 | 0.014 |

Adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, household income, employment, depression, knee injury and knee surgery, smoking, physical activity, body mass index, NSAIDs use, baseline K-L grade, weight change, the changes of rim distance and beam angle, other dairy products (yogurt, cheese), and other dietary factors intake (total calories, fat, grain, vegetable and fruit, meat, fish, soft drink, dietary and supplement vitamin A, C, D, E).

In sensitivity analysis, we evaluated the association between calcium intake and JSW change. Consistent with milk consumption, the highest quartile of dietary calcium intake was associated with reduced JSW decrease compared to the lowest quartile in women (adjusted means: 0.33 mm versus 0.24mm, p=0.025), but not in men. After including dietary calcium intake in the model, the effect of milk consumption was attenuated by 25% (the difference of JSW change between ≥7 glasses/week and no milk intake decreased from 0.12 mm to 0.09 mm). In addition, we did not observed any significant interactions between milk intake and race, smoking, obesity, physical activity, K-L grade and vitamin D intake in men and women

Table 3 shows the multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of OA progression evaluated by time to the first increase of semi-quantitative OARSI score. Consistent with JSW analysis, after adjustment for covariates, we found a significant inverse association between milk intake and the risk of OA progression in women. With increasing levels of milk intake, the HR were 0.67 (95% CI, 0.50-0.91), 0.71 (95% CI, 0.50-1.00) and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.38-0.81) respectively compared to no milk consumption (p trend 0.008). In men, we found that only the ≥7 glasses/week of milk intake reduced the risk of OA progression.

Table 3.

Association of milk intake with rate of OA progression measured by the decrease of joint space narrowing score (JSN, OARSI grades 0-3)

| glasses / week |

Men |

Women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HR (95% CI)* | P trend | N | HR (95% CI)* | P trend | |

| None | 133 | Referent | 238 | Referent | ||

| ≤3 | 342 | 0.77(0.53,1.13) | 473 | 0.67(0.50,0.91) | ||

| 4-6 | 173 | 0.92(0.60,1.40) | 246 | 0.71(0.50,1.00) | ||

| ≥7 | 240 | 0.61(0.39,0.94) | 0.075 | 303 | 0.56(0.38,0.81) | 0.008 |

Hazard ratio and 95% confident interval, adjusted for age, race, education, marital status, household income, smoking, physical activity, employment, body mass index, depression, NSAIDs use, knee injury and knee surgery, baseline K-L grade, other dairy products (yogurt, cheese), and other dietary factors intake (total calories, fat, grain, vegetable and fruit, meat, fish, soft drink, dietary and supplement vitamin A, C, D, E).

Discussion

In this 48-month follow-up study of people with radiographic knee OA, we found an inverse dose-response relationship of milk consumption with structural progression of knee OA measured by both quantitative and semi-quantitative JSN independent of other potential covariates in women, but in men, only ≥7 glasses/week milk consumption was associated with reduced progression of knee OA.

Knee OA progression has been thought to involve multiple mechanisms besides cartilage loss including changes in bone composition and shape, as well as proprioreception,(27-29) which might be subject to the influences of macro and micronutrients in the diet. McAlindon et al. reported that a higher consumption of anti-oxidant micronutrients, especially vitamin C, might decrease cartilage loss and OA progression, (8) and low vitamin D intake and low serum vitamin D levels might increase the risk for progression of knee OA. (7) However, few studies investigated the association of milk consumption and progression of OA. In a cross-sectional study using face-to-face interview, frequency of symptomatic knee OA was significantly lower in daily milk consumers.(14) A 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study investigated the effects of a nutritional supplement beverage containing milk-based micronutrients and fortified with vitamins and minerals on pain symptoms and activity in adults with osteoarthritis. They found that daily consumption of a nutritional beverage containing milk-based micronutrients, vitamins and minerals was beneficial in alleviating symptoms and dysfunction in subjects with osteoarthritis. (13)

Milk contains many of the nutrients that are required daily including calcium, phosphorus, and protein and is voluntarily fortified with vitamin D in the United States. Milk components take part in metabolism in several ways; by providing essential amino acids, vitamins, minerals and fatty acids, or by affecting absorption of nutrients. (30) Several clinical trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation showed that it can reduce bone loss and lower the risk of bone fractures.(31, 32) Our results indicated that milk consumption may reduce knee OA progression partially through elevated dietary calcium intake. Nevertheless, the biologic mechanism for an effect of milk consumption on the radiographic progression of OA remains unclear.

In our analysis, we adjusted for major dietary factors, such as, total calories, total fat, total grain, fish, meat, vegetable, fruit consumption intake and vitamin A, C, D, E dietary intake and supplementation. It is possible that vitamins, minerals, soluble fiber, and phytochemicals in healthy beverages may have beneficial effects confounding with potential effects of milk intake. Moreover, we also adjusted for other dairy products (yogurt, cheese) intake, and the association remained. Milk intake (mainly low-fat or fat free milk) may also be a marker of general healthy diet which may improve OA progression. Inconsistent with milk, our results indicated that cheese consumption may increase knee OA progression. The high saturated fat acids containing in cheese may be associated with the pathogenesis of OA. (33, 34) A recent study reported that increased consumption of saturated fatty acids was associated with an increased incidence of bone marrow lesions, which may predict knee OA progression.(33)

In addition, we found the effect of milk in OA progression differs in men and women. Sex differences have been noted in the prevalence, incidence, and severity of OA for many years. (35) Faber and colleagues found cartilage thickness of the distal femur to be less in women than in men. (36) Other evidences suggested a protective effect of exogenous estrogen on cartilage and bone turnover. (37) In current study, women had much lower intake of dietary calcium than men (averaged 715 mg/day in men, 647mg/d in women, p<0.001). If dietary calcium is a possible mediation factor to link between milk consumption and knee OA progression, women may be more sensitive for the effect of calcium intake through milk than men. However the gender differences in the relationship of milk consumption with OA progression are not completely understood.

The strengths of this study include the prospective design, large number of subjects with knee OA, and the state-of-the-art quantitative measures of structural change from sophisticated image processing technology. The quantitative software based assessment provides a more precise measure of JSW in millimeters and permits the assessor to document appreciable change in JSW in the tibiofemoral compartment (16, 17) We also used the semi-quantitative OARSI score as the measure of JSN to confirm our findings. In addition, we excluded knees in which the difference of rim distance between follow-up and baseline visits was ≥2mm and adjusted for changes of rim distance and beam angle in the multivariate models to minimize the possible measurement error of radiographic data.

Because of the observational nature of the study, patients were not randomly assigned to milk intake groups. We cannot prove that the observed associations are causal because residual confounding could theoretically affect the observed associations. However, we controlled for potential confounding by most known risk factors that are plausibly associated with diet and OA progression. We did not control for any treatments, but no treatments have been proved to reduce radiographic OA progression, and related to milk consumption. With only baseline dietary data, imprecise measurement could potentially have influenced our observed associations. However, random errors in dietary assessment measures would more likely account for a lack of association but not the reverse. Although the quantitative approach provided a precise measure of JSW, there is no clinical criterion in JSW change available to evaluate the severity of knee OA progression. In addition, detailed information for the consumption of each type of milk (high-fat, low-fat and fat-free milk) was not available. However, more than 90% OAI participants only drank fat-free or low-fat milk. High-fat milk may be associated with an increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease or other chronic conditions. Therefore, the preferable effect of low-fat or fat-free milk on OA progression may be stronger than our current findings.

In conclusion, our study suggested that frequent milk intake may be associated with reduced OA progression in women. Replication of these novel findings in other prospective studies demonstrating the increase in milk consumption leads to delay in OA progression are needed to test this hypothesis.

Significance and Innovations.

There are scarce data on the possible role of diet on OA progression. We found frequent milk consumption may be a significant protective factor for OA progression in women.

The state-of-the-art quantitative measures of structural change from computerized technology.

Consistent findings using both quantitative and semi-quantitative measures of joint space narrowing.

Prospective design, large number of subjects with knee OA.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this analysis was provided by contract HHSN268201000020C - Reference Number: BAA-NHLBI-AR-10-06 -National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. This manuscript has received the approval of the OAI Publications Committee based on a review of its scientific content and data interpretation. The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Pfizer, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Merck Research Laboratories; and GlaxoSmithKline. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the funding source

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Contract number: HHSN268201000020C, Reference Number: BAA-NHLBI-AR1006). The study sponsor was not involved in the study design, data analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Competing Interests There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Yelin EH, Song J, Chang RW. The costs of arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003 Feb 15;49(1):101–13. doi: 10.1002/art.10913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008 Jan;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reginster JY. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2002 Apr;41(Supp 1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT. An update on the pathogenesis and epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2004 Jan;42(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(03)00161-1. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garstang SV, Stitik TP. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2006 Nov;85(11 Suppl):S2–11. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000245568.69434.1a. quiz S2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlindon T, Felson DT. Nutrition: risk factors for osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1997 Jul;56(7):397–400. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.7.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlindon TE, Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Aliabadi P, Weissman B, et al. Relation of dietary intake and serum levels of vitamin D to progression of osteoarthritis of the knee among participants in the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Sep 1;125(5):353–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAlindon TE, Jacques P, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Aliabadi P, Weissman B, et al. Do antioxidant micronutrients protect against the development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis and rheumatism. 1996 Apr;39(4):648–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heaney RP. Dairy and bone health. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2009 Feb;28(Suppl 1):82S–90S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin S. Dairy products and bone health. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007 Jan;107(1):35. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.11.037. author reply -6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver CM, Heaney RP. Dairy consumption and bone health. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2001 Mar;73(3):660–1. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 7th. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colker CM, Swain M, Lynch L, Gingerich DA. Effects of a milk-based bioactive micronutrient beverage on pain symptoms and activity of adults with osteoarthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical evaluation. Nutrition. 2002 May;18(5):388–92. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00800-0. Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kacar C, Gilgil E, Tuncer T, Butun B, Urhan S, Sunbuloglu G, et al. The association of milk consumption with the occurrence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004 Jul-Aug;22(4):473–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The osteoarthritis initiative protocol for the cohort study. < http://oai.epi-.csf.org/datarelease/docs/StudyDesignProtocol.pdf>; [accessed 04.25.2012]

- 16.Duryea J, Zaim S, Genant HK. New radiographic-based surrogate outcome measures for osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2003 Feb;11(2):102–10. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp JT, Angwin J, Boers M, Duryea J, von Ingersleben G, Hall JR, et al. Computer based methods for measurement of joint space width: update of an ongoing OMERACT project. The Journal of rheumatology. 2007 Apr;34(4):874–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duryea J, Neumann G, Niu J, Totterman S, Tamez J, Dabrowski C, et al. Comparison of radiographic joint space width with magnetic resonance imaging cartilage morphometry: analysis of longitudinal data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis care & research. 2010 Jul;62(7):932–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.20148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guermazi A, Hunter DJ, Roemer FW. Plain radiography and magnetic resonance imaging diagnostics in osteoarthritis: validated staging and scoring. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. 2009 Feb;91(Suppl 1):54–62. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block G, Hartman AM, Naughton D. A reduced dietary questionnaire: development and validation. Epidemiology. 1990 Jan;1(1):58–64. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Sep;124(3):453–69. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993 Feb;46(2):153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansen KL, Painter P, Kent-Braun JA, Ng AV, Carey S, Da Silva M, et al. Validation of questionnaires to estimate physical activity and functioning in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001 Mar;59(3):1121–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin DY. Cox regression analysis of multivariate failure time data: the marginal approach. Statistics in medicine. 1994 Nov 15;13(21):2233–47. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780132105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yusuf E, Kortekaas MC, Watt I, Huizinga TW, Kloppenburg M. Do knee abnormalities visualised on MRI explain knee pain in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011 Jan;70(1):60–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanamas SK, Wluka AE, Pelletier JP, Pelletier JM, Abram F, Berry PA, et al. Bone marrow lesions in people with knee osteoarthritis predict progression of disease and joint replacement: a longitudinal study. Rheumatology. Dec;49(12):2413–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq286. Oxford, England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Driban JB, Lo GH, Lee JY, Ward RJ, Miller E, Pang J, et al. Quantitative bone marrow lesion size in osteoarthritic knees correlates with cartilage damage and predicts longitudinal cartilage loss. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2011;12:217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haug A, Hostmark AT, Harstad OM. Bovine milk in human nutrition--a review. Lipids in health and disease. 2007;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson-Hughes B. Calcium supplementation and bone loss: a review of controlled clinical trials. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1991 Jul;54(1 Suppl):274S–80S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.1.274S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson-Hughes B, Dallal GE, Krall EA, Harris S, Sokoll LJ, Falconer G. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on wintertime and overall bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Oct 1;115(7):505–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-7-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Davies-Tuck ML, Wluka AE, Forbes A, English DR, Giles GG, et al. Dietary fatty acid intake affects the risk of developing bone marrow lesions in healthy middle-aged adults without clinical knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis research & therapy. 2009;11(3):R63. doi: 10.1186/ar2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felson DT, McLaughlin S, Goggins J, LaValley MP, Gale ME, Totterman S, et al. Bone marrow edema and its relation to progression of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Sep 2;139:330–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_1-200309020-00008. 5 Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2005 Sep;13(9):769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faber SC, Eckstein F, Lukasz S, Muhlbauer R, Hohe J, Englmeier KH, et al. Gender differences in knee joint cartilage thickness, volume and articular surface areas: assessment with quantitative three-dimensional MR imaging. Skeletal radiology. 2001 Mar;30(3):144–50. doi: 10.1007/s002560000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linn S, Murtaugh B, Casey E. Role of sex hormones in the development of osteoarthritis. Pm R. 2012 May;4(5 Suppl):S169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]