Abstract

Arginases are a family of enzymes that convert L-arginine to L-ornithine and urea. Alterations in expression of the isoform arginase-I are increasingly recognized in lung diseases such as asthma and cystic fibrosis. To define expression of murine arginase-I in formalin-fixed tissues, including lung, an immunohistochemical protocol was validated in murine liver; a tissue that has distinct zonal arginase-I expression making it a useful control. In the lung, arginase-I immunostaining was observed in airway surface epithelium and this decreased from large to small airways; with a preferential staining of ciliated epithelium versus Clara cells and alveolar epithelia. In submucosal glands, the ducts and serous acini had moderate immunostaining, which was absent in mucous cells. Focal immunostaining was observed in alveolar macrophages, endothelial cells, pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes, pulmonary artery smooth muscle, airway smooth muscle and neurons of ganglia of the lung. Arginase-I immunostaining was also detected in other tissues including salivary glands, pancreas, liver, skin, and intestine. Differential immunostaining was observed between sexes in submandibular salivary glands; arginase-I was diffusely expressed in the convoluted granular duct cells of females, but was rarely noted in males. Strain specific differences were not detected. In one mouse with an incidental case of lymphoma, neoplastic lymphocytes lacked arginase-I immunostaining, in contrast to immunostaining detected in non-neoplastic lymphocytes of lymphoid tissues. The use of liver tissue to validate arginase-I immunohistochemistry produced consistent expression patterns in mice and this approach can be useful to enhance consistency of arginase-I immunohistochemical studies.

Keywords: Arginine, Arginase, Arginase I, Lung, Immunohistochemistry, Cystic Fibrosis, Asthma, Liver

INTRODUCTION

L-Arginine (arginine) is a basic amino acid that plays a key role in cellular homeostasis of many tissues.1 Arginine synthesis does occur in mammals, primarily via the intestinal-renal axis, but it may also be required in the diet at certain stages of development or in some disease conditions; for that reason, arginine is considered a semi-essential essential amino acid.1-3 In contrast, arginine catabolism occurs through multiple pathways. In particular, the arginase family of enzymes is a major pathway for arginine degradation. It is composed of two important isoforms: arginase-I and arginase-II; each converts L-arginine to L-ornithine and urea.4,5 Arginase-I is a cytosolic enzyme and is most commonly recognized as a hepatocellular enzyme, whereas arginase-II is a mitochondrial enzyme that is believed to be widely expressed in many tissues. There is increasing evidence that alterations in arginine metabolism may contribute major disease processes including obesity/metabolic syndrome,6-8 cardiovascular disease,9,10 cancer,11 and chronic lung diseases such as asthma and cystic fibrosis.12-14 The exact mechanism(s) for these associations are not clear, but some have suggested that competition with the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) pathway for arginine substrate could alter NOS-mediated physiologic events. For example, in the lung the NOS pathway regulates important functions like vasodilation, airway tone and inflammation. Because of these disease associations, arginases are increasingly studied in disease pathogenesis and as potential targets for therapeutic intervention.15,16

In research, histotechnology and immunohistochemistry techniques are commonly used to help address scientific questions through study of tissues in humans and animal models.17-19 Many factors go into the development of an immunohistochemical protocol (reagent concentration, time, temperature, etc), which influence the final immunostaining quality and specificity.20,21 Use of well-defined positive and negative control tissues are valuable tools in any immunohistochemical procedure. In that light, the murine liver has arginase-I expression in zone 1-2 hepatocytes, but is absent in zone 3 hepatocytes22,23 - making the liver an excellent control tissue for arginase-I immunohistochemical procedures. Arginase-I immunohistochemical techniques have been reported in rat and mouse tissues for evaluation of tissue expression.24-25 However, many arginase-I studies lack identification of positive and negative control tissues that were purportedly used in the immunohistochemical procedure. The absence of appropriate and consistent controls between different studies could contribute to excessive background staining or inconsistent reports of expression patterns, which converge to make valid scientific interpretations from multiple studies difficult.

The goals of this study were to validate an immunohistochemical protocol using the murine liver as a control tissue and apply this protocol in select tissues with arginase-I expression. Given the increasingly recognized role of arginase-I in pulmonary diseases, cellular arginase-I expression in the lung was targeted for study. Ancillary goals were to evalute for possible sex or strain differences in arginase-I expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissues

All animal and tissue work was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. B6J and BALB/cJ mice were examined as these are two commonly used strains for research investigations and if strain differences were present it could significantly impact scientific studies. B6J (females and males, 3/sex, 5-8 months old) and BALB/cJ (2 females, 5 weeks of age and 1 male 4.5 months of age) control mice were euthanized as part of other ongoing studies. This is consistent with the three R’s of Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement to avoid excessive use of animals in research studies. B6J mice were the core of the study and the BALB/cJ mice were evaluated to determine if there were possible strain differences. Select tissues (salivary gland chain, lung, pancreas, intestine, skin, liver) were collected based on arginase-I expression patterns from an in situ hybridization study.23 Tissues were collected immediately following euthanasia, placed in fixative (10% neutral buffered formalin, ~72 hours, room temperature) with ~20:1 volume fixative:tissue and placed on a rotary table for the first 24 hours.

Arginase-I Immunohistochemistry

The liver was used as the primary tissue for arginase-I immunohistochemistry because it has distinct expression in zones 1-2 and lack of expression in zone 3.22-23 The final protocol (see below) was validated based on serial gradation in primary antibody concentration that yielded arginase-I expression in zone 1-2 hepatocytes with distinct absence of expression in zone 3 hepatocytes. As a review, liver zones 1 through 3 progressively define hepatocytes closest to the portal tract (zone 1) through the mid zonal region (zone 2) and finally closest to the central vein (zone 3).

After fixation, tissues were routinely processed (Tissue-Tek VIP 6 Processor, Sakura Finetek, USA Inc.), paraffin embedded (Histostar Embedding Station, Thermo Scientific), and sectioned (~4 μm, RM 2155 Automated Microtome, Leica) onto slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher Scientific). Tissues were baked (60 degrees C, 60 minutes, Isotemp Oven, Fisher Scientific). Slides were then hydrated through xylene and alcohol baths and finally to buffer (DAKO 1X Buffer, DAKO, “buffer” for rest of procedure). Tissues were then placed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and processed for heat induced epitope retrieval (Decloaking Chamber™, Biocare Medical) for 5 minutes at 125°C. Solution with the slides was allowed to cool on the countertop to room temperature for 20 minutes. Slides were washed in deionized water followed by buffer. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched by immersion in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 8 minutes followed by rinses with buffer (2 times × 5 minutes each). Additional background was blocked with a commercial product (Background Buster, Innovex Company) followed by buffer rinse. Primary anti-arginase-I antibody (1:300 dilution, rabbit polyclonal, #sc-20150, Santa Cruz Company) or matched rabbit serum (negative controls) were applied for 60 minutes followed by buffer washes (2 washes × 5 minutes each). A commercial secondary kit (Rabbit Envision HRP System, DAKO) was applied according to manufacturer’s recommendations (30 minutes) and followed by buffer washes (2 washes × 5 minutes each). Chromogen (DAB Plus, DAKO) was applied to tissues for 5 minutes followed by buffer rinses, DAB Enhancer (3 minutes, DAKO) and rinses in deionized water. Tissues were then counterstained (1 minute, Surgipath hematoxylin, Leica Microsystems), washed (tap water), and blued in Scott’s Tap Water (in house). Finally, slides were dehydrated through a progressive series of alcohol and xylene baths, mounted (Mount Quick, Newcomer Supply) and coverslipped. Tissues were examined by a veterinary pathologist. Because the numbers per group were limited and tissue scoring was not employed,26 tissues were examined in an unmasked fashion to evaluate the study. Digital images were collected with a DP73 camera and CellSens software (Olympus).

RESULTS

Select tissues were identified from previous in situ hybridization data as having arginase-I expression23 and these were studied for arginase-I immunostaining (Table 1). First, the immunohistochemical procedure was validated in the liver through observation of arginase-I immunostaining in zone 1-2 hepatocytes with an absence in zone 3 hepatocytes (Figure 1A, Table 1) as expected for its expression23. In this study, the distinction between positive (zone 1-2) and negative hepatocellular staining (zone 3) was obvious and appropriately located, validating the procedure. Within in the liver, bile ducts and gallbladder epithelium also had weak to moderate immunostaining.

Table 1.

Arginase-1 expression patterns in select murine tissues.

| Organ | Arginase-1 immunostaining | Lack of immunostaining |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Liver | Hepatocytes (zones 1-2) | Hepatocytes (zone 3) |

| Bile duct | ||

| Gallbladder epithelium | ||

|

| ||

| Pancreas | Islets (peripheral individual cells) | Acini |

| Ducts | ||

|

| ||

| Skin | Follicle (anagen bulb > adnexa) | Follicle (inner root sheath) |

| Surface epithelium | ||

|

| ||

| Intestine | Surface epithelium | Paneth cells |

| Lamina propria (lymphoid cells) | ||

| Ganglia (neurons) | ||

| Smooth muscle (focal) | ||

|

| ||

| Salivary glands (Submandibular, SM; Sublingual, SL; Parotid, P) | Ducts (SM, P, SL) | Acini (SM) |

| Acini (SL, P - multifocal weak/moderate) | Convoluted granular duct cells (males - negative except for rare positive cell) | |

| Convoluted granular duct cells (females) | ||

|

| ||

| Lung | Submucosal glands (serous acini, ducts) | Submucosal glands (mucous acini/tubules) |

| Surface epithelium (ciliated > Clara cell, alveoli) | Lymph node (tingible body macrophages) | |

| Alveolar macrophages (weak in healthy animals, abundant in some during disease) | ||

| Smooth muscle (focal) | ||

| Pulmonary vein cardiac muscle (focal) | ||

| Ganglia (neurons) | ||

| Vasculature (endothelium, smooth muscle) | ||

| Lymph node (cortex, paracortex > germinal center) | ||

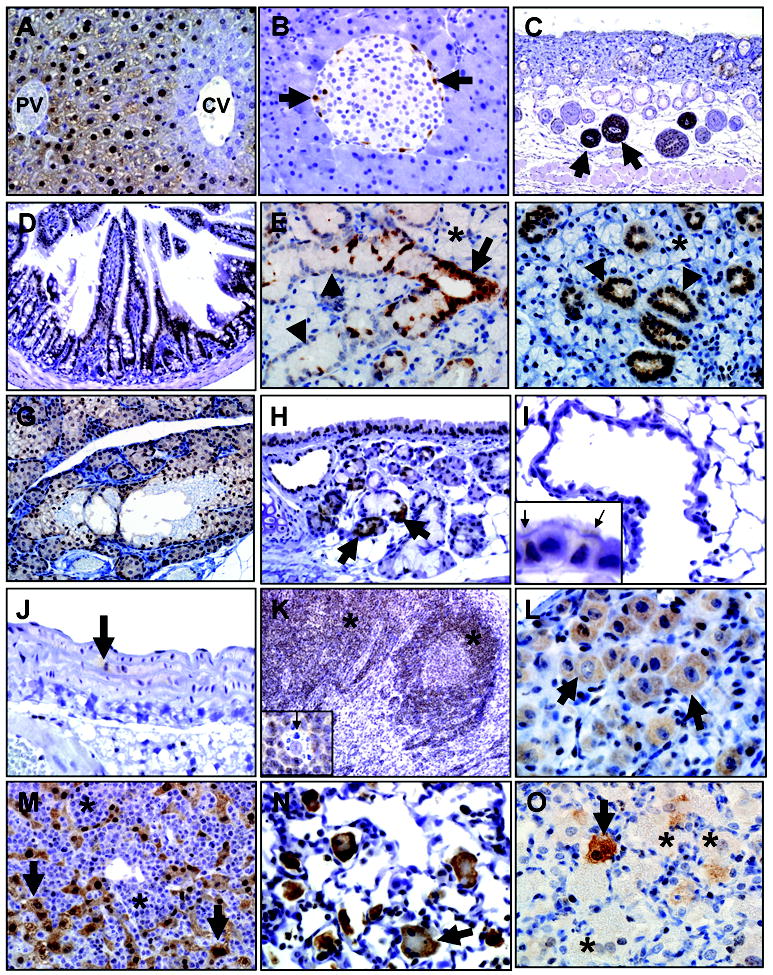

Figure 1.

Arginase-I immunohistochemistry in select mouse tissues. A) Liver, B6 mouse. Arginase-I was detected in zone 1 and 2 hepatocytes near the terminal portal vein (PV) but was absent in zone 3 hepatocytes (blue staining) near the central vein (CV). B) Pancreas, BALB/c mouse. Arginase-I was detected in solitary islet cells (arrows) often the periphery of the islets, but was generally absent in acinar cells. C) Skin, BALB/c mouse. Arginase-I immunostaining was robustly detected in the bulb (arrows) of anagen hair follicles. D) Small intestine, B6 mouse. Arginase-I was detected in surface epithelium. E, F) Submandibular salivary gland of male (E) and female (F) B6 mice. Arginase-I was detected in gland’s striated ducts (E, arrow), but acini lacked arginase-I expression (asterisks, E & F). Interestingly, the convoluted granular duct cells that have sexual dimorphism also showed sex-based differences with arginase-I diffusely detected in female granular duct cells (arrowheads, F) but lacking in male granular duct cells (arrowheads, E). G) Zymbol gland, B6 mouse. Arginase-I was expressed in most of the glands, but lacking in the fibrovascular stroma (blue staining). H) Tracheal submucosal glands, B6 mouse. Arginase-I was detected in submucosal gland ducts and serous acini (arrows), whereas submucosal gland mucous cells lacked expression. I) Lung, B6 mouse. Distal airway and alveolar epithelium generally lacked or had weak arginase-I immunostaining. Inset: Arginase-I expression was preferential expressed in ciliated epithelial cells (arrows) compared to adjacent Clara cells (adjacent blue staining nonciliated cells) that often lacked expression. J) Elastic artery, B6 mouse. Focal arginase-I immunostaining was detected in smooth muscle cells (arrow) of the tunica media. K) Lymph node, BALB/c mouse. Arginase-I was detected in cortex (asterisks) mostly in lymphoid cells. Inset: arginase-I staining lymphoid cells surrounding an unstained tingible body macrophage (arrow). L) Ganglion, B6 mouse. Arginase-I is selectively detected in neurons (arrows) of the ganglion. M) Lymphoma effacing liver, B6 mouse. Neoplastic lymphocytes (asterisks) lack arginase-I expression (compare to Figure 1K) while remnant hepatocytes (arrows) retain arginase-I expression (compare to Figure 1A). N,O) Lung macrophages associated with the previous lymphoma case (see Figure 1M) or Pneumocystis murina infection (N and O, respectively). Arginase-I expression was detected in many activated macrophages and multinucleate macrophages (arrow, N) in the lymphoma lung (N), but in the P. murina lung arginase-I was detected in solitary macrophages (arrow, O) adjacent to other macrophages that lacked arginase-I expression (asterisks, O).

Other tissues were examined for arginase-I immunostaining. The pancreas had arginase-I immunostaining in solitary cells along the periphery of the pancreatic islets (Figure 1B). Immunostaining was also seen in ducts with a general lack of expression in exocrine acini. The skin had robust arginase-I immunostaining in bulbs of anagen follicles (Figure 1C) along with less intense immunostaining in the adnexal sebaceous glands and surface epithelium. The intestine had arginase-I immunostaining in the surface epithelium (Figure 1D), but it was absent in Paneth cells. Intestinal immunostaining was also seen in neurons of ganglia, lymphoid cells of the Peyer’s patches and focally in smooth muscle.

Salivary glands had immunostaining in duct epithelium, but acinar immunostaining was weak/moderate and multifocal (sublingual, parotid) or absent (submandibular). The sublingual salivary gland had acinar immunostaining that was not associated with intracellular mucus. In the submandibular salivary gland, convoluted granular duct cells normally exhibit sexual dimorphism with male having large prominent granular ducts cells compared to females.27 Here, granular duct cells had diffuse arginase-I immunostaining in females, but immunostaining was uncommon in males (Figure 1 E & F). In addition, Zymbol glands, a modified sebaceous gland near the ear base, had diffuse arginase-I expression in the glands and ducts (Figure 1G), but expression was lacking in its fibrovascular stroma.

The lungs were examined for cellular expression of arginase-I (Table 1). Submucosal glands had immunostaining in ducts and serous cells with a lack of immunostaining in mucous cells (Figure 1H). In surface epithelium of airways, arginase-I expression was seen in large airways including trachea with less immunostaining in small airways. This distribution seemed to correlate, in part, with preferential immunostaining for ciliated cells over Clara cells (Figure 1H & I). Arginase-I was focally detected in smooth muscle (vascular and airway) (Figure 1J) and vascular endothelium. Similarly, focal immunostaining was seen in cardiomyocytes that line the wall of pulmonary venules. Pulmonary lymph nodes had arginase-I expression in the cortex predominantly in mononuclear/lymphoid cells, but immunostaining was absent in tingible body macrophages within germinal centers (Figure 1K). A few cases had mild perivascular lymphoid infiltration and these lymphocytes had similar immunostaining. Ganglia, occasionally detected along the trachea, had neurons with immunostaining as well (Figure 1L).

In this study, incidental disease was diagnosed in two B6J mice. One mouse had systemic lymphoma (Figure 1 M & N) and neoplastic lymphoma cells lacked arginase-I expression (Figure 1M). In the lung of the same case, alveolar septa were focally hypercellular with neoplastic lymphocytes and the adjacent alveolar macrophages were activated (e.g. enlarged, multinucleate) with robust arginase-I immunostaining (Figure 1N). The second mouse was diagnosed with pulmonary Pneumocystis murina infection, which is characterized by alveolar filling and distention by large macrophages, fungal organisms and debris.28,29 Interestingly, only a small number of alveolar macrophages had intense immunostaining (Figure 1O) whereas many lacked arginase-I immunostaining.

Discussion

In this study, an arginase-I immunohistochemical protocol was validated using the murine liver and then arginase-I immunostaining was studied in select tissues. Use of the liver as a control tissue consistently produced immunostaining in arginase-I expressing cells while minimizing nonspecific staining in negative cells.

Immunohistochemical tissue expression (Table 1) in our study was similar to expression patterns reported for in situ hybridization of arginase-I (e.g. zone 1-2 distribution in liver, activated alveolar macrophages, peripheral cells in pancreatic islets, salivary gland ducts, etc.).23 Even so there were some minor differences in tissue expression such as serous gland acini, which was reported to have diffuse in situ hybridization and yet only had multifocal immunostaining in the current study. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between message and protein expression patterns is through cell regulation mechanisms such as translational repression.30 Further studies using serial sections for ISH and IHC may be useful to address this issue.

An interesting finding in the current study was the observation of novel sex differences in the granular duct cells of the submandibular salivary glands. A previous report that studied arginase-I immunohistochemistry in the salivary glands showed similar cellular localization to the our study however, they did not observe (nor did they specifically look for) sex differences in the granular duct cells.24 Examination of the methods in that report shows that it did not clearly identify the sex or numbers of the mice studied, further suggesting that the intent of the paper was not to examine for sex-based differences. Importantly, publications (such as the previous report24) that include study of murine arginase-I immunohistochemistry often do not use (or show) tissue controls such as the liver in their reports and this may be an additional source of variability in scientific interpretation.

A curiosity in this study was the common presence of nuclear and cytoplasmic immunostaining in even though arginase-I is described as a cytoplasmic enzyme. Some might contest that the nuclear immunostaining is a nonspecific pattern and this study cannot definitively rebuke such a challenge. However, there are data that could suggest the immunostaining to be biologically relevant. The liver (Figure 1A) clearly had nuclear and cytoplasmic immunostaining in zone 1-2 hepatocytes that similarly decreased and became absent in zone 3 hepatocytes, consistent with arginase-I expression patterns expected for the murine liver. Furthermore, numerous immunohistochemical studies have reported or published images with similar cytoplasmic and nuclear immunostaining for arginase-I.31-34 Lastly, cytoplasmic proteins can, at times, be inappropriately translocated to the nucleus. For example, during cellular infection of canine distemper virus, the viral N-protein can be trafficked from the cytoplasm to the nucleus along with heat shock proteins as part of a cell stress response,35 creating atypical intranuclear inclusions in addition to the expected cytoplasmic viral inclusions. Likewise, arginases have been described to colocalize with some types of chaperone proteins.36,37 Additional studies (e.g. using confocal microscopy) may be needed to fully dissect these cellular trafficking of arginase-I.

Arginase-I immunostaining was consistently detected in lymphocytes of this study. In mice, lymphocytes have a inconsistent record of arginase-I expression with some studies providing evidence that it is expressed by lymphocytes23,38 and others suggesting it is not.39 The lack of arginase-I expression in the case of lymphoma was interesting since lymphoid cells depend on arginine for normal function and arginase-I administration is the basis of novel therapies against lymphoma.16 Alveolar macrophages are another type of immune cell normally found in the lung that had nominal immunostaining in the healthy mice, but during disease had variable increases in arginase-I expression. Increased arginase-I expression can be detected in macrophages and is a phenotypic characteristic of an alternatively activated (M2) macrophages.40 Arginase-I expression in various and dynamic populations of leukocytes accentuates the significance of microscopic observation to supplement and validate arginase-I expression assays of whole tissues including the lung.

Evaluation of arginase-I expression in the lung was an important component of this study. Unlike humans and other major species where the submucosal glands extend through intrapulmonary bronchi, murine submucosal glands are restricted to the proximal extrapulmonary airways and trachea.41 Arginase-I immunostaining was detected in submucosal glands (serous, duct cells) and preferentially in ciliated epithelium of the surface epithelium. However, arginase-I expression in airway epithelium is dynamic and can be upregulated (including Clara cells) in disease states such as mouse models of asthma.42 Arginase-I expression in smooth muscle is also relevant in the lung because it can compete with nitric oxide synthases (NOS) for arginine. NOS convert arginine to nitric oxide, a potent mediator of smooth muscle relaxation in pulmonary vessels and airways.43,44 Understanding of the tissue expression patterns between arginase-I and NOS in health and disease may be useful to dissect out the pathogenesis of smooth muscle phenotypes often seen in models of lung disease.45-48

In conclusion, standardization of arginase-I immunohistochemical evaluations through consistent use of murine control tissue will only improve scientific assessment and comparisons between future studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (grant HL51670 and HL091842), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant DK54759), and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST - none

References

- 1.Wu G, Bazer FW, Davis TA, Kim SW, Li P, Rhoads JM, et al. Arginine metabolism and nutrition in growth, health and disease. Amino Acids. 2009;37:153–168. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marion V, Sankaranarayanan S, de Theije C, van Dijk P, Lindsey P, Lamers MC, et al. Arginine deficiency causes runting in the suckling period by selectively activating the stress kinase GCN2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8866–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu G, Morris SM., Jr Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond. Biochem J. 1998;336:1–17. doi: 10.1042/bj3360001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cederbaum SD, Yu H, Grody WW, Kern RM, Yoo P, Iyer RK. Arginases I and II: do their functions overlap? Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81:S38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Meininger CJ, Hawker JR, Jr, Haynes TE, Kepka-Lenhart D, Mistry SK, et al. Regulatory role of arginase I and II in nitric oxide, polyamine, and proline syntheses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E75–E82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.1.E75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu WJ, Haynes TE, Kohli R, Hu J, Shi W, Spencer TE, et al. Dietary L-arginine supplementation reduces fat mass in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:714–721. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucotti P, Setola E, Monti LD, Galluccio E, Costa S, Sandoli EP, et al. Beneficial effect of a longterm oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. AmJ Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E906–E912. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z, Satterfield MC, Bazer FW, Wu G. Regulation of brown adipose tissue development and white fat reduction by L-arginine. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:529–38. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283595cff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pieper GM. Acute amelioration of diabetic endothelial dysfunction with a derivative of the nitric oxide synthase cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1997;29:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu G, Meininger CJ. Arginine nutrition and cardiovascular function. J Nutr. 2000;130:2626–2629. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo MT, Savaraj N, Feun LG. Targeted cellular metabolism for cancer chemotherapy with recombinant arginine-degrading enzymes. Oncotarget. 2010;1:246–51. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasemann H, Schwiertz R, Matthiesen S, Racké K, Ratjen F. Increased arginase activity in cystic fibrosis airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1523–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-253OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasemann H, Shehnaz D, Enomoto M, Leadley M, Belik J, Ratjen F. L-ornithine derived polyamines in cystic fibrosis airways. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maarsingh H, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Arginase: a key enzyme in the pathophysiology of allergic asthma opening novel therapeutic perspectives. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:652–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grasemann H, Tullis E, Ratjen F. A randomized controlled trial of inhaled l-Arginine in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2013 Jan 14; doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez CP, Morrow K, Lopez-Barcons LA, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Velasco C, et al. Pegylated arginase I: a potential therapeutic approach in T-ALL. Blood. 2010;115:5214–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson-Corley KN, Hochstedler C, Sturm M, Rogers J, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Successful Integration of the Histology Core Laboratory in Translational Research. J Histotechnol. 2012;35:17–21. doi: 10.1179/2046023612Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivier AK, Naumann P, Goeken A, Hochstedler C, Sturm M, Rodgers JR, et al. Genetically modified species in research: Opportunities and challenges for the histology core laboratory. J Histotechnol. 2012;35:63–67. doi: 10.1179/2046023612y.0000000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung C, Churg A, Wright J, Elliott MW. Effects of isopropanol storage time on histochemical and immunohistochemical stains in lung tissue. J Histotechnol. 2011;34:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos-Vara JA. Technical aspects of immunohistochemistry. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:405–26. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-4-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richendrfer HA, Wetzel JA, Swann JM. Temperature, Peroxide Concentration, and Immunohistochemical Staining Method Affects Staining Intensity, Distribution, and Background. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17:543–546. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181a91595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine S, Ogawa R, Mcmanus MT, Kanai Y, Hebrok M. Dicer is required for proper liver zonation. J Pathol. 2009;219:365–72. doi: 10.1002/path.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu H, Yoo PK, Aguirre CC, Tsoa RW, Kern RM, Grody WW, et al. Widespread expression of arginase I in mouse tissues. Biochemical and physiological implications. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:1151–60. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akiba T, Kuroiwa N, Shimizu-Yabe A, Iwase K, Hiwasa T, Yokoe H, et al. Expression and regulation of the gene for arginase I in mouse salivary glands: requirement of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha for the expression in the parotid gland. J Biochem. 2002;132:621–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi S, Park C, Ahn M, Lee JH, Shin T. Immunohistochemical study of arginase 1 and 2 in various tissues of rats. Acta Histochem. 2012;114:487–94. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson-Corley KN, Olivier AK, Meyerholz DK. Principles for valid histopathologic scoring in research. Vet Pathol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0300985813485099. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treuting PM, Dintzis SM. Salivary glands. In: Treuting PM, Dintzis SM, editors. Comparative Anatomy and Histology: A Mouse and Human Atlas. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, USA: 2012. pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson MP, Christmann BS, Werner JL, Metz AE, Trevor JL, et al. IL-33 and M2a alveolar macrophages promote lung defense against the atypical fungal pathogen Pneumocystis murina. J Immunol. 2011;186:2372–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treuting PM, Clifford CB, Sellers RS, Brayton CF. Of mice and microflora: considerations for genetically engineered mice. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:44–63. doi: 10.1177/0300985811431446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange PS, Langley B, Lu P, Ratan RR. Novel roles for arginase in cell survival, regeneration, and translation in the central nervous system. J Nutr. 2004;134:2812S–2817S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2812S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, et al. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol. 2001;167:6533–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krings G, Ramachandran R, Jain D, Wu TT, Yeh MM, Torbenson M, Kakar S. Immunohistochemical pitfalls and the importance of glypican 3 and arginase in the diagnosis of scirrhous hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2013 Jan 25; doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.243. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Que LG, Kantrow SP, Jenkinson CP, Piantadosi CA, Huang YC. Induction of arginase isoforms in the lung during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(1 Pt 1):L96–102. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.1.L96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan BC, Gong C, Song J, Krausz T, Tretiakova M, Hyjek E, et al. Arginase-1: a new immunohistochemical marker of hepatocytes and hepatocellular neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1147–54. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e5dffa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oglesbee M, Krakowka S. Cellular stress response induces selective intranuclear trafficking and accumulation of morbillivirus major core protein. Lab Invest. 1993;68:109–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGee DJ, Kumar S, Viator RJ, Bolland JR, Ruiz J, Spadafora D, et al. Helicobacter pylori thioredoxin is an arginase chaperone and guardian against oxidative and nitrosative stresses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3290–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endo M, Oyadomari S, Terasaki Y, Takeya M, Suga M, et al. Induction of arginase I and II in bleomycin-induced fibrosis of mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003 Aug;285(2):L313–21. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00434.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenyon NJ, Bratt JM, Linderholm AL, Last MS, Last JA. Arginases I and II in lungs of ovalbumin-sensitized mice exposed to ovalbumin: sources and consequences. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, Ortiz B, Zea AH, Piazuelo MB, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5839–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyerholz DK, Rodgers J, Castilow EM, Varga SM. Alcian Blue and Pyronine Y histochemical stains permit assessment of multiple parameters in pulmonary disease models. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:325–8. doi: 10.1354/vp.46-2-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.North ML, Khanna N, Marsden PA, Grasemann H, Scott JA. Functionally important role for arginase 1 in the airway hyperresponsiveness of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L911–20. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00025.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali NK, Jafri A, Sopi RB, Prakash YS, Martin RJ, Zaidi SI. Role of arginase in impairing relaxation of lung parenchyma of hyperoxia-exposed neonatal rats. Neonatology. 2012;101:106–15. doi: 10.1159/000329540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang M, Rangasamy D, Matthaei KI, Frew AJ, Zimmmermann N, Mahalingam S, et al. Inhibition of arginase I activity by RNA interference attenuates IL-13-induced airways hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2006;177:5595–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyerholz DK, Stoltz DA, Namati E, Ramachandran S, Pezzulo AA, Smith AR, et al. Loss of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function produces abnormalities in tracheal development in neonatal pigs and young children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1251–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0643OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoltz DA, Rokhlina T, Ernst SE, Pezzulo AA, Ostedgaard LS, Karp PH, et al. Intestinal CFTR Expression Alleviates Meconium Ileus in Cystic Fibrosis Pigs. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(6):2685–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI68867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ostedgaard LS, Meyerholz DK, Chen J, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Rokhlina T, et al. The ΔF508 mutation causes CFTR misprocessing and cystic fibrosis–like disease in pigs. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:74ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koziol-White CJ, Panettieri RA., Jr Airway smooth muscle and immunomodulation in acute exacerbations of airway disease. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:178–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]