Abstract

Drug development is an expensive process that is marked by a high-failure rate. For this reason early stage bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies are essential in determining the fate of new drug products. In this study, we sought to systematically assess the current trends of ongoing and recently completed bioequivalence and bioavailability trials that have been registered within a national clinical trials registry. All bioequivalence and bioavailability studies registered in the United States ClinicalTrials.gov registry from late-2007 through 2011 were identified. Over this period, more than 2300 interventional bioequivalence and bioavailability trials were registered. As of 2013, the vast majority of studies (86%) have been completed, 10% are actively recruiting participants, and the remainder are engaged in data analysis (4%). When compared to completed trials, ongoing trials are in later phases of clinical development, recruiting larger numbers of participants, and more likely to recruit women and children (P<0.001 for all). These data suggest that the quality of bioequivalence and bioavailability studies has improved rapidly, even over the last five years. However, further work is needed to sustain – and accelerate – these improvements in the design of bioequivalence and bioavailability studies to ensure that safe and efficacious medicines swiftly reach healthcare providers and their patients.

Keywords: Clinical trials, Biomedical research, Healthcare reform, Pharmaceutics

Introduction

Many drug patents have recently expired or are scheduled to expire in the near future [1]. In response, many drug manufacturers have expanded their generic drug portfolio, which requires them to conduct clinical trials that demonstrate that their generic equivalents perform similarly to the innovator drug product [2]. Regulations introduced by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) over the last thirty-five years have strengthened measures to ensure the bioequivalency of drug products, which may be simultaneously manufactured by multiple drug makers [3-5]. Bioequivalence and bioavailability testing standards have also emerged following recognition that bioinequivalence and variations in the bioavailability of drug products can result in therapeutic failure and/or toxicity [6-8].

In the United States, the successful approval of new and abbreviated new drug applications requires regulatory approval by the FDA [9]. Recent studies have suggested that this process takes nearly a decade to complete the required series of pre-clinical studies and clinical trials [10]. Drug development is an expensive process that is marked by a high-failure rate [11]. For these reasons, early stage bioequivalence and pharmacokinetic studies are essential in determining the fate of new drug products.

In this study, we sought to systematically assess the current trends of ongoing and recently completed bioequivalence and bioavailability trials that have been registered within a national clinical trials registry. This study provides insight regarding the characteristics of current bioequivalence and bioavailability trials and may also provide assistance in prioritizing future areas of research.]

Methods

Selection of bioequivalence and bioavailability trials

We identified bioequivalence and bioavailability trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov using the key words “bioequivalence” and “bioavailability”. Briefly, ClinicalTrials.gov is a publicly-available registry of clinical research studies that is maintained by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. As of mid-2013 there were nearly 150,000 studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, with study sites in 185 countries (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Our search was restricted to identify studies registered between 01 October 2007 and 31 December 2012 to coincide with the enactment of a federal law in 2007 that mandated the registration of all phase 2-4 interventional trials involving drugs, biological agents, and medical devices [12]. We excluded all observational trials (n=34) as well as trials that were “suspended” (n=7), “terminated” (n=33), or “withdrawn” (n=26). The remaining trial registry entries were systematically examined and the following data elements were extracted: a unique trial identifier, study title, recruitment status, phase (0-4), study design, blinding status, interventional assignment to trial arms, primary endpoint classification, primary purpose of the trial, age group and gender eligibility criteria, and anticipated enrollment size.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the bioequivalence and bioavailability trials identified in the ClinicalTrials.gov registry. Comparisons between ongoing trials and those that have been completed were performed using the χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared with the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. All statistical analyses were undertaken in Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Trial characteristics

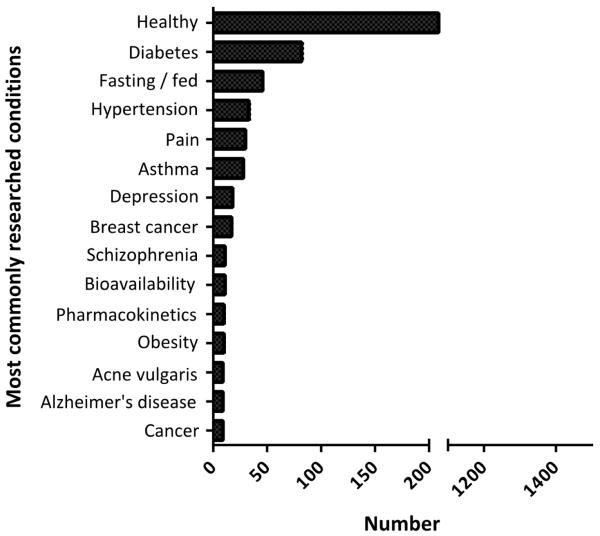

From October 2007 through December 2012 there were 2,388 interventional bioequivalence and bioavailability trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. Of these, 227 (10%) trials are actively recruiting participants, 15 (1%) are recruiting by invitation only, 87 (4%) are engaged in data analysis, and 2,059 (86%) have been completed. The 15 most commonly investigated disease states / conditions are featured in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the 15 most commonly researched disease states / conditions among bioequivalence and bioavailability studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov.

A comparison of ongoing and completed clinical trial characteristics is presented in Table 1. Ongoing bioequivalence and bioavailability trials are more likely to be in later phase clinical trials, as reflected by a decrease in the proportion of phase 0, 1, and 1/2 trials from 75% among completed studies to 36% of ongoing studies (P<0.001). Ongoing trials are also more likely to be double-blinded (27% vs. 12%; P<0.001) and have larger sample sizes (P<0.001). Similarly, ongoing trials are more likely to feature parallel group assignment and less likely to be crossover trials (P<0.001 for both). There has also been an increase in the proportion of trials that primarily involved research on treatments from 42% to 55% (P<0.001). The proportion of trials that exclusively recruited male participants declined from 20% to 9% (P<0.001) and the number of trials that enrolled children increased from 3% to 17% (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Interventional bioequivalence and bioavailability clinical trial characteristics among ongoing and completed trials.

| Characteristic | Category | Bioequivalence & Bioavailability Trials | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing (n = 227) | Completed (n = 2,161) | ||

| Study phase, n (%) | Phase 0, 1, 1/2 | 82 (36) | 1,625 (75) |

| Phase 2, 2/3 | 31 (14) | 51 (2) | |

| Phase 3, 4 | 57 (25) | 120 (6) | |

| Unknown / missing | 57 (25) | 365 (17) | |

| Allocation status, n (%) | Randomized | 172 (76) | 1,955 (90) |

| Non-randomized | 21 (9) | 94 (4) | |

| Unknown / missing | 34 (15) | 112 (5) | |

| Blinding, n (%) | Open | 141 (62) | 1,751 (81) |

| Single blind | 24 (11) | 114 (5) | |

| Double blind | 62 (27) | 252 (12) | |

| Unknown / missing | 0 (0) | 44 (2) | |

| Interventional group, n (%) | Single group | 55 (24) | 151 (7) |

| Parallel | 98 (43) | 249 (12) | |

| Cross-over | 69 (30) | 1,707 (79) | |

| Factorial | 5 (2) | 8 (<1) | |

| Unknown / missing | 0 (0) | 46 (2) | |

| Endpoint classification, n (%) | Bioavailability | 47 (21) | 418 (19) |

| Bioequivalence | 108 (48) | 1,270 (59) | |

| Efficacy | 14 (6) | 26 (1) | |

| Pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics | 16 (7) | 239 (11) | |

| Safety | 14 (6) | 64 (3) | |

| Safety / efficacy | 18 (8) | 20 (1) | |

| Unknown / missing | 10 (4) | 124 (6) | |

| Primary purpose, n (%) | Treatment | 125 (55) | 911 (42) |

| Basic science | 28 (12) | 317 (15) | |

| Prevention | 20 (9) | 61 (3) | |

| Diagnostic | 17 (7) | 20 (1) | |

| Health services research | 3 (1) | 16 (1) | |

| Supportive care | 6 (3) | 7 (<1) | |

| Screening | 0 (0) | 7 (<1) | |

| Missing | 28 (12) | 822 (38) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female only | 21 (9) | 113 (5) |

| Male only | 20 (9) | 424 (20) | |

| Both | 186 (82) | 1,616 (75) | |

| Unknown / missing | 0 (0) | 8 (<1) | |

| Age groups, n (%) | Children only | 17 (7) | 30 (1) |

| Children and adults | 23 (10) | 48 (2) | |

| Adults only | 187 (82) | 2,083 (96) | |

| Expected sample size, median (IQR) | 50 (24 – 104) | 32 (24 – 48) | |

Geographic distribution

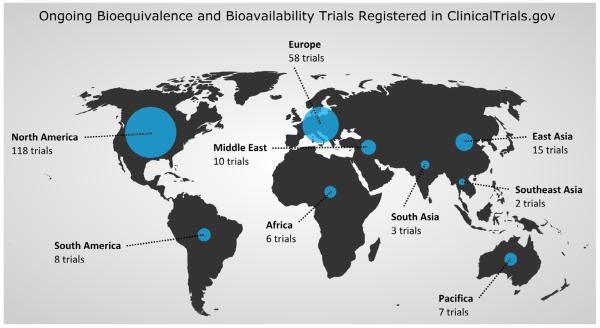

More than half of the bioequivalence and bioavailability trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov were conducted internationally (58%). Among ongoing trials, 48% are being conducted at sites located outside of North America. The global distribution of ongoing bioequivalence and bioavailability trials is shown in Figure 2. The majority of ongoing trials are recruiting participants in North America (52%) and Europe (26%); however, East Asia (7%), the Middle East (4%), and South America (4%) are also involved in several ongoing bioequivalence and bioavailability trials.

Figure 2.

Global distribution of ongoing bioequivalence and bioavailability trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov in 2013. The size of the blue circles denotes the number of ongoing clinical trials within each geographic region.

Discussion

This study reveals that bioequivalence and bioavailability trials are part of a global clinical research enterprise. When compared to completed trials, ongoing trials are in later phases of clinical development, recruiting larger numbers of participants, and more likely to recruit women and children. These data suggest that bioequivalence and bioavailability studies are undergoing a transformation as drug makers seek to characterize the safety and efficacy of drug products in more rigorous trials that closely resemble their anticipated patient population.

As the costs of healthcare and drug development have risen, there is a mounting incentive for improving our understanding of existing treatments while also enabling breakthrough discoveries [13]. Recently, the United Kingdom has attempted to strategically align their clinical research funding with their public health priorities [14]. Although similar measures have not been enacted in the United States, it behooves policy makers to consider the vital role that bioequivalence and bioavailability studies play in bringing new and generic drug products to the public. As noted here, the quality of bioequivalence and bioavailability studies has improved rapidly, even over the last five years, and the horizon is bright. However, as the national debate on healthcare reform and research priorities unfolds we may need to re-evaluate our approach to bioequivalence and bioavailability trials to ensure that safe and efficacious medicines swiftly reach healthcare providers and their patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [grant number U01A1082482] (to KA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [grant number U18IP000303] (to CS and KA). This work was further supported by the Primary Children’s Medical Center Foundation.

Abbreviations

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NLM

National Library of Medicine

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

References

- 1.Harrison C. Patent watch: the patent cliff steepens. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:12–13. doi: 10.1038/nrd3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patnaik RN, Lesko LJ, Chen ML, Williams RL. Individual bioequivalence. New concepts in the statistical assessment of bioequivalence metrics. FDA Individual Bioequivalence Working Group. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:1–6. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.1977;42 Federal Register 1648. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Food and Drug Administration Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21. Food and Drugs. 2012 Part 320 Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Requirements. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbeeck RK, Musuamba FT. The revised EMA guideline for the investigation of bioequivalence for immediate release oral formulations with systemic action. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;15:376–388. doi: 10.18433/j3vc8j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer MC, Straughn AB, Jarvi EJ, Wood GC, Pelsor FR, et al. The bioinequivalence of carbamazepine tablets with a history of clinical failures. Pharm Res. 1992;9:1612–1616. doi: 10.1023/a:1015872626887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindenbaum J, Mellow MH, Blackstone MO, Butler VP., Jr Variation in biologic availability of digoxin from four preparations. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1344–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112092852403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aguiar AJ, Krc J, Jr, Kinkel AW, Samyn JC. Effect of polymorphism on the absorption of chloramphenicol from chloramphenicol palmitate. J Pharm Sci. 1967;56:847–853. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600560712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank RG. The ongoing regulation of generic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1993–1996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichert JM. Trends in development and approval times for new therapeutics in the United States. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nrd1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse T, Williams RJ, Zarin DA. Update on Registration of Clinical Trials in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest. 2009;136:304–305. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch BR, Califf RM, Cheng SK, Tasneem A, Horton J, et al. Characteristics of oncology clinical trials: insights from a systematic analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:972–979. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stead M, Cameron D, Lester N, Parmar M, Haward R, et al. Strengthening clinical cancer research in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1529–1534. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]