Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopeptidases that regulate cell-matrix composition and are also involved in processing various bioactive molecules such as cell-surface receptors, chemokines, and cytokines. Our group recently reported that MMP-3, -8, and -9 are upregulated during microglial activation and play a role as proinflammatory mediators (Lee et al., 2010, 2014). In particular, we demonstrated that MMP-8 has tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-converting enzyme (TACE) activity by cleaving the prodomain of TNF-α and that inhibition of MMP-8 inhibits TACE activity. The present study was undertaken to compare the effect of MMP-8 inhibitor (M8I) with those of inhibitors of other MMPs, such as MMP-3 (NNGH) or MMP-9 (M9I), in their regulation of TNF-α activity. We found that the MMP inhibitors suppressed TNF-α secretion from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated BV2 microglial cells in an order of efficacy: M8I>NNGH>M9I. In addition, MMP inhibitors suppressed the activity of recombinant TACE protein in the same efficacy order as that of TNF-α inhibition (M8I>NNGH>M9I), proving a direct correlation between TACE activity and TNF-α secretion. A subsequent pro-TNF-α cleavage assay revealed that both MMP-3 and MMP-9 cleave a prodomain of TNF-α, suggesting that MMP-3 and MMP-9 also have TACE activity. However, the number and position of cleavage sites varied between MMP-3, -8, and -9. Collectively, the concurrent inhibition of MMP and TACE by NNGH, M8I, or M9I may contribute to their strong anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.

Keywords: Microglia, Inflammation, MMP inhibitor, TNF-α, TACE

INTRODUCTION

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), also called matrixins, are Zn2+-dependent endopeptidases that degrade extracellular matrix proteins. MMPs are involved in normal brain development, plasticity, angiogenesis, and repair following brain injury (Agrawal et al., 2008; Verslegers et al., 2013). However, MMPs are aberrantly expressed in various neuropathological conditions and can cause breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, infiltration of peripheral immune cells, demyelination, and neuronal cell death (Rosenberg, 2009; Morancho et al., 2010). There is growing evidence that MMPs are involved in neuroinflammatory disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (Candelario-Jalil et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2012; Javaid et al., 2013). Recently, our group reported that several MMPs are upregulated in activated microglia and play an important role as proinflammatory mediators (Woo et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010, 2014). Thus, MMPs have been considered a key therapeutic target for treatment of various neurological disorders.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine, mediates inflammation, cell activation, and cell migration (Aggarwal et al., 2003). TNF-α contributes to the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier by modulating soluble guanylyl cyclase and protein tyrosine kinase (Mayhan, 2002). TNF-α also plays a crucial role in the neuroinflammatory responses of activated microglia (Aggarwal et al., 2003; McCoy and Tansey, 2008). TNF-α is primarily produced as a homotrimeric, 26-kDa, non-glycosylated, type II protein on the plasma membrane, which is cleaved by TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) between Ala76–Val77 and released as a 17-kDa soluble protein (Gearing et al., 1995; Black et al., 1997; Moss et al. 1997). TACE is also known as a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)-17, a member of the ADAM proteases family, which is implicated in various inflammatory diseases, including arthritis, diabetes, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (Asai et al, 2003; Moss et al., 2008; Kataoka, 2009). Therefore, TACE inhibition is an attractive strategy for controlling the level of active TNF-α in order to treat inflammatory disorders (Bahia and Silakari, 2010).

Recently, we demonstrated that MMP-3, -8, and -9 mediate inflammatory reactions through cleavage and activation of protease-activated receptor-1 in α-synuclein-stimulated microglia (Lee et al., 2010). In addition, we showed that MMP-8 plays a pivotal role in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation by modulating TNF-α activation (Lee et al., 2014). However, the detailed mechanisms of TNF-α modulation by MMP-3 and MMP-9 in activated microglia have not been demonstrated until now. In the present study, we investigated the effect of three kinds of MMP-specific inhibitors (inhibitors specific for either MMP-3, -8, or -9) on TNF-α production in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells and compared the efficacy of each MMP inhibitor in the processing of pro-TNF-α. Furthermore, using a pro-TNF-α cleavage assay, we compared the TACE functions of MMP-3, -8, and -9. Our data collectively suggest that dual modulation of TNF-α and MMPs by MMP inhibitors such as NNGH, M8I, and M9I may provide potential therapeutic advantages for treatment of neuroinflammatory disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

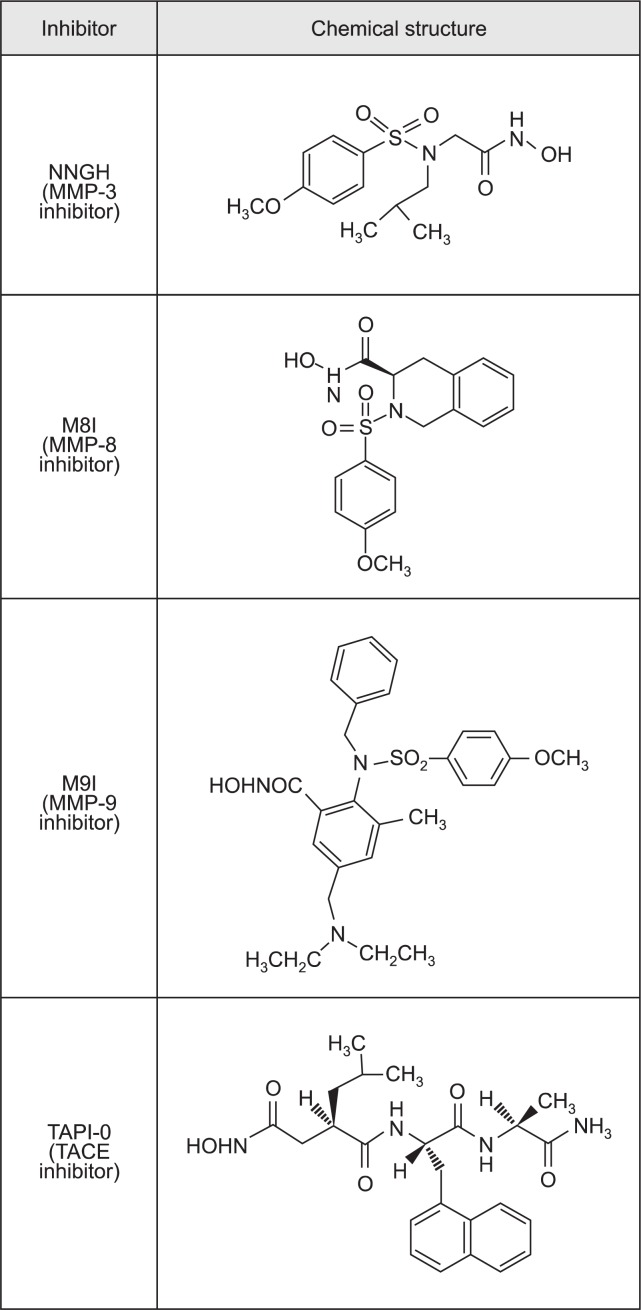

LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). MMP-3 inhibitor (NNGH), MMP-8 inhibitor (M8I), and MMP-9 inhibitor (M9I) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). The chemical structures of the MMP inhibitors are illustrated in Fig. 1. The recombinant TACE protein was supplied by R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). TAPI-0, recombinant MMP-3, MMP-8, and MMP-9 proteins were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Lausen, Switzerland). All cell-culture reagents were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise stated.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the MMP inhibitors and TAPI-0. NNGH, N-Isobutyl-N-(4-methoxyphenylsulfonyl)-glycylhydroxamic acid; MMP-8 inhibitor (M8I), (3R)-(+)-[2-(4-Methoxybenzenesulfonyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroiso quinoline-3-hydroxamate]; MMP-9 inhibitor (M9I), 2-(N-benzyl-4-methoxyphenylsulfonamido)-5-((diethylamino) methyl)-N-hydroxy-3-methylbenzamide; TAPI-0, N-(R)-(2-(Hydroxyaminocarbonyl)methyl)-4-methylpentanoyl-L-naphthylalanyl-L-alanine amide.

BV2 microglial cell cultures

The immortalized murine BV2 microglial cells (Bocchini et al., 1992) were grown and maintained at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, streptomycin (10 μg/ml), and penicillin (10 U/ml).

Measurement of TNF-α levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

BV2 cells (1×105 cells per well in a 48-well plate) were pretreated with various concentrations (0–100 μM) of NNGH, M8I, or M9I for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 3 h. The supernatants of the cultured microglia were then collected, and the TNF-α concentration was measured by ELISA according to the procedure recommended by the supplier (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). To measure the amount of TNF-α in cell lysates, BV2 cells were lysed in PBS by 10 passes through a 26-gauge needle. Cells were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000×g, and supernatant was taken for determination of intracellular TNF-α level by ELISA.

Determination of TACE enzymatic activity

TACE activity was assayed using the SensoLyteTM 520 TACE activity assay kit (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA). Recombinant protein (rhTACE or rhMMP, 250 ng) with TAPI-0 or MMP inhibitor (0.1, 0.5, or 1 μM) were incubated with TACE substrate. TACE activity was then determined by continuous detection of peptide cleavage in wells for 30–60 min using a fluorescence plate reader. TACE activity was expressed as the change in fluorescence intensity at excitation of 490 nm/emission of 520 nm.

Pro-TNF-α cleavage assay

A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based pro-TNF-α cleavage assay was performed to identify interactions between pro-TNF-α and MMP-3 or MMP-9 using residues 71–82 (Ac-S71PLAQAVRSSSR82-NH2) (Peptron, Daejeon, South Korea) (Minond et al., 2012). For the reaction, 2 μM pro-TNF-α was digested by 1 nM MMP (MMP-3 or -9) or 0.5 nM TACE. The effects of MMP-specific inhibitor or TAPI-0 on TNF-α cleavage were also determined by digesting pro-TNF-α for 1 h with MMP-3, -9 (1 nM) or TACE (0.5 nM) in the absence or presence of MMP-specific inhibitor (80 nM) or TAPI-0 (5 nM).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise stated, all experiments were performed with triplicate samples and repeated at least three times. The data are presented as means ± S.E.M., and statistical comparisons between groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Comparison of the effects of MMP inhibitors on the release of TNF-α from LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells

To examine the effects of MMP inhibitors on TNF-α secretion, BV2 cells were pretreated with one of the three kinds of MMP inhibitor for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml). After a 3-h incubation with LPS, the supernatants were removed from cultured cells, and the TNF-α concentration was measured. The percent release of TNF-α was determined by dividing the amount of TNF-α in the supernatant by the total amount of TNF-α (cell-associated+secreted TNF-α). As shown in Fig. 2A, LPS led to secretion of approximately 88% of TNF-α into the cell culture media, whereas pretreatment with MMP inhibitors suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α secretion in a dose-dependent manner. Among the three types of inhibitors, the inhibitory effect of M8I was most prominent, followed by NNGH and M9I. Intriguingly, the cell-associated TNF-α levels were not significantly altered by the MMP inhibitors. The results suggest that MMP inhibitors are mainly involved in the secretion of the active form of TNF-α.

Fig. 2.

Effect of three kinds of MMP inhibitors on TNF-α secretion in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglial cells. (A) Effect of MMP inhibitors on TNF-α secretion in conditioned media and on TNF-α expression in cell lysates. BV2 microglial cells were incubated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 3 h in the absence or presence of NNGH, M8I, or M9I. Cell lysates were prepared by passage through a 26-gauge needle, and the production of TNF-α in conditioned media and cell lysates was determined by ELISA. The average values are indicated. (B) The percent release of TNF-α was determined by dividing the amount of TNF-α in the supernatant by the total amount of TNF-α (cell-associated + secreted TNF-α). The data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. n=4–6 per group. *p<0.05 vs. LPS-treated cells.

Comparison of the effects of MMP inhibitors on TACE enzymatic activity

TNF-α is produced as a proform (26 kDa) and secreted in an active form (17 kDa) after cleavage of its prodomain by TACE (Bahia and Silakari, 2010). To further dissect the mechanism of the effects of MMP inhibitors on TNF-α secretion, we examined whether three types of MMP inhibitors inhibit TACE activity using recombinant human TACE protein (rhTACE). Consistent with the TNF-α secretion data, the MMP inhibitors inhibited TACE activity of rhTACE in an efficacy order of M8I>NNGH>M9I. Of note, M8I and NNGH suppressed the TACE activity significantly more than TAPI-0, a general TACE inhibitor. The IC50 of each inhibitor of TACE activity of rhTACE are shown in Fig. 3B. We previously reported that MMP-8 itself has TACE activity (Lee et al., 2014). To address whether MMP-3 and MMP-9 also have TACE activity, we performed the TACE enzymatic assay using recombinant proteins (rhMMP-3, rhMMP-9). Indeed, rhMMP-3 and rhMMP-9 also showed TACE activity, with rhMMP-8 being more active than rhMMP-3 and rhMMP-9 being the least active (Fig. 3C). TACE activity of MMP proteins was reduced by TAPI-0 or their own MMP inhibitor (data not shown), supporting the specificity of cleavage reactions.

Fig. 3.

Effect of MMP inhibitors on TACE activity of rhTACE and TACE function of recombinant MMP-3, MMP-8, and MMP-9 proteins. (A) Effect of MMP inhibitors (NNGH, M8I, M9I) and TAPI-0 on TACE enzymatic activity. Recombinant human (rh) TACE protein (250 ng) was premixed with NNGH, M8I, M9I, or TAPI-0. After 30 min, the fluorogenic TACE substrate was added to the mixture of TACE and inhibitor, and the fluorescence was measured as described in the Methods section. The data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. n=4 per group. *p<0.05, significantly different from TACE activity of rhTACE. (B) IC50 values of MMP inhibitors and TAPI-0 on TACE activity of rhTACE are summarized. (C) TACE activities of rhMMP-3, rhMMP-8, and rhMMP-9 protein (250 ng) were determined as described in the Methods section.

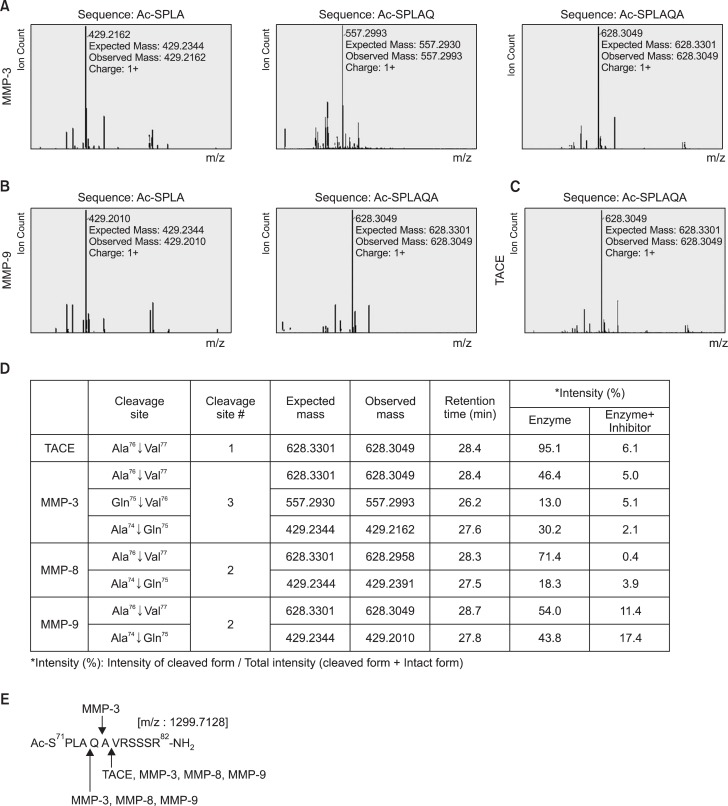

MMP-3 and MMP-9 cleave a prodomain of TNF-α with more cleavage sites than TACE

We previously reported that MMP-8 has TACE activity by demonstrating the cleavage of the active site of proTNF-α (A76/V77, A74/Q75) (Lee et al., 2014). To address whether active MMP-3 and MMP-9 also directly cleave the prodomain of TNF-α, we performed a TNF-α cleavage assay using LCMS analysis. Like rhTACE, MMP-3 and MMP-9 cleaved the A76/V77 residue, a conventional cleavage site in the N-terminal propeptide of TNF-α (Fig. 4A–C). Interestingly, additional cleavage sites were identified with rhMMP-3 (A74/Q75, Q75/A76) and rhMMP-9 (A74/Q75) (Fig. 4). To confirm that the cleavage reaction was specifically induced by MMP-3 or MMP-9, their specific inhibitors (NNGH, M9I) were added to the reaction mixture. As expected, no meaningful products were produced (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that MMP-8 and MMP-9 have TACE activity through their cleavage of two specific sequences in pro-TNF-α, whereas MMP-3 cleaves three sites (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

TNF-α cleavage assay using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. (A–D) The 12-residue peptide covering pro-TNF-α cleavage sites was incubated with active rhMMP proteins (MMP-3 or -9) or rhTACE and analyzed by LC-MS. Cleavage profiles of pro-TNF-α by MMP-3 (A), MMP-9 (B) and TACE (C). (D) Summary of enzyme activities of TACE and MMPs by comparing cleaved sequences of pro-TNF-α based on LC-MS data. The data obtained from TACE and MMP-8 protein were previously reported (Lee et al., 2014). (E) Summary of pro-TNF-α sites cleaved by TACE and MMPs.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we compared the efficacy of chemical inhibitors of MMPs in the regulation of TNF-α in the context of microglial activation. We observed that MMP inhibitors inhibited TNF-α secretion and TACE activity in an efficacy order of M8I>NNGH>M9I (Fig. 2, 3). Interestingly, we found that MMP-3, -8, and -9 themselves have TACE enzymatic activity by cleaving the prodomain of TNF-α (Fig. 3). A subsequent TNF-α cleavage assay identified cleavage sites of the prodomain of TNF-α by each MMP (Fig. 4). Although MMP-3, -8, and -9 commonly cleaved a conventional cleavage site in the N-terminal propeptide of TNF-α, one or two additional cleavage sites were identified depending on the MMP (Fig. 4E).

Because MMPs are involved in various acute and chronic diseases such as arthritis, multiple sclerosis, atherosclerosis, stroke, and cancer, many pharmaceutical companies are actively developing compounds that can be used to block their action. The major synthetic inhibitors of MMPs are based on a hydroxamate structure (Hu et al., 2007; Dev et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014). The hydroxamates interfere with the action of the zinc catalytic domain in the MMP molecule. Except for the conserved catalytic center Zn2+ of MMPs, there are two hydrophobic domains (S1’ and S2’ pocket, respectively), which are located in proximity to the catalytic zinc center. In particular, the S1’ pocket is known to be a major domain that distinguishes the selectivity of various MMPs and is mostly involved in substrate specificity of certain MMPs (Verma and Hansch, 2007). The MMP inhibitors (NNGH, M8I, M9I) used in the present study are also hydroxamate-based inhibitors with specificity to MMP-3, MMP-8, or MMP-9, respectively. The inhibition of TACE activity by MMP inhibitors may be related to this hydroxamate structure because TACE also has a zinc ligand binding motif (Bahia and Silakari, 2010). Therefore, the different functional side chains surrounding hydoxamate MMP inhibitors might be factors affecting not only substrate specificity, but also efficacy of TACE inhibition. Further studies are necessary to identify the structural-functional relationship regarding TNF-α /TACE inhibition by MMP inhibitors.

We previously reported that administration of M8I significantly inhibits microglial activation and expression/secretion of TNF-α in the brain tissue, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid of LPS-induced septic mice (Lee et al., 2014). Furthermore, administration of M8I reduced brain damage, microglial activation, and TNF-α expression in cerebral ischemia-challenged mouse brains (unpublished data). Considering that TNF-α is a key proinflammatory cytokine that mediates neuroinflammation and neuronal cell death, efficient inhibition of TNF-α by MMP inhibitors may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of various neuroinflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (Grant #2012R1A2A2A01045821 & 2012R1A5A2A32671866).

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal BB. Signaling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal SM, Lau L, Yong VW. MMPs in the central nervous system: where the good guys go bad. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai M, Hattori C, Szabó B, Sasagawa N, Maruyama K, Tanuma S, Ishiura S. Putative function of ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 as APP α-secretase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahia MS, Silakari O. Tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme: an encouraging target for various inflammatory disorders. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2010;75:415–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2010.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchini V, Mazzolla R, Barluzzi R, Blasi E, Sick P, Kettenmann H. An immortalized cell line expresses properties of activated microglial cells. J Neurosci Res. 1992;31:616–621. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E, Yang Y, Rosenberg GA. Diverse roles of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in neuroinflammation and cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev R, Srivastava PK, Iyer JP, Dastidar SG, Ray A. Therapeutic potential of matrix metalloprotease inhibitors in neuropathic pain. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;19:455–468. doi: 10.1517/13543781003643486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing AJ, Beckett P, Christodoulou M, Churchill M, Clements JM, Crimmin M, Davidson AH, Drummond AH, Galloway WA, Gilbert R, Gordon JL, Leber TM, Mangan M, Miller K, Nayee P, Owen K, Patel S, Thomasv W, Wells G, Wood LM, Woolley K. Matrix metalloproteinases and processing of pro-TNF-alpha. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:774–777. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Van den Steen PE, Sang QXA, Opdenakker G. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Dicsov. 2007;6:480–498. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaid MA, Abdallah MN, Ahmed AS, Sheikh Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and their pathological upregulation in multiple sclerosis: an overview. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s13760-013-0239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H. EGFR ligands and their signaling scissors, ADAMs, as new molecular targets for anticancer treatments. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;56:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Woo MS, Moon PG, Baek MC, Choi IY, Kim WK, Junn E, Kim HS. α-Synuclein activates microglia by inducing the expressions of matrix metalloproteases and the subsequent activation of protease-activated receptor-1. J Immunol. 2010;185:615–623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Han JE, Woo MS, Shin JA, Park EM, Kang JL, Moon PG, Baek MC, Son WS, Ko YT, Choi JW, Kim HS. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 plays a pivotal role in neuroinflammation by modulating TNF-α activation. J Immunol. 2014;193:2384–2393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li NG, Tang YP, Duan JA, Shi ZH. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: a patent review (2011 – 2013) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;24:1039–1052. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.937424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhan WG. Cellular mechanisms by which tumor necrosis factor-α produces disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2002;927:144–152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy M, Tansey MG. TNF signaling inhibition in the CNS: implications for normal brain function and neurodegenerative disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minond D, Cudic M, Bionda N, Giulianotti M, Maida L, Houghten RA, Fields GB. Discovery of novel inhibitors of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) using glycosylated and non-glycosylated substrates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36473–36487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morancho A, Rosell A, García-Bonilla L, Montaner J. Matrix metalloproteinase and stroke infarct size: role for anti-inflammatory treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, Bickett DM, Burkhart W, Carter HL, Chen WJ, Clay WC, Didsbury JR, Hassler D, Hoffman CR, Kost TA, Lambert MH, Leesnitzer MA, McCauley P, McGeehan G, Mitchell J, Moyer M, Pahel G, Rocque W, Overton LK, Schoenen F, Seaton T, Su JL, Becherer JD. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385:733–736. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss ML, Sklair-Tavron L, Nudelman R. Drug insight: tumor necrosis factor-converting enzyme as a pharmaceutical target for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:300–309. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases and their multiple roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:205–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Ma L, Kaarela T, Li Z. Neuroimmune crosstalk in the central nervous system and its significance for neurological diseases. J. Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:155. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma RP, Hansch C. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs): Chemical-biological functions and (Q)SARs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:2223–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verslegers M, Lemmens K, Hove IV, Moons L. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 as promising benefactors in development, plasticity and repair of the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;105:60–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo MS, Park JS, Choi IY, Kim WK, Kim HS. Inhibition of MMP-3 or -9 suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines and iNOS in microglia. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:770–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]