Abstract

Esophageal reflux of gastric contents causes esophageal mucosal damage and inflammation. Recent studies show that oxygen-derived free radicals mediate mucosal damage in reflux esophagitis (RE). Chlorogenic acid (CGA), an ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid, is one of the most abundant polyphenols in the human diet and possesses anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and anti-oxidant activities. In this context, we investigated the effects of CGA against experimental RE in rats. RE was produced by ligating the transitional region between the forestomach and the glandular portion and covering the duodenum near the pylorus ring with a small piece of catheter. CGA (10, 30 and 100 mg/kg) and omeprazole (positive control, 10 mg/kg) were administered orally 48 h after the RE operation for 12 days. CGA reduced the severity of esophageal lesions, and this beneficial effect was confirmed by histopathological observations. CGA reduced esophageal lipid peroxidation and increased the reduced glutathione/oxidized glutathione ratio. CGA attenuated increases in the serum level of tumor necrosis factor-α, and expressions of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 protein. CGA alleviates RE-induced mucosal injury, and this protection is associated with reduced oxidative stress and the anti-inflammatory properties of CGA.

Keywords: Chlorogenic acid, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Inflammation, Oxidative stress, Reflux esophagitis

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition that develops when reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus leads to mucosal damage and its sequelae. The incidence of GERD is estimated to be 10–20% in Western countries, making it one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders (Dent et al., 2005). The existing therapeutic strategy for GERD is aimed primarily at reducing gastric acidity by the administration of anti-secretory agents such as H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Despite their well-known efficacy, a number of patients have experienced relapse, incomplete mucosal healing or ensuing complications, suggesting the involvement of targets other than acid secretion in the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis (RE) (Katz, 2003).

The development of RE is more consistent with immune-mediated injury than with injury caused by the toxic effects of acid, emphasizing the orchestration of chemokine and cytokine secretion and inflammatory cell migration, including T cell and neutrophils (Souza et al., 2009). An imbalance in the generation of free radicals, especially reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cellular antioxidant capacity leads to a state of oxidative stress, which is also critical in the etiology of RE in both animals and human subjects (Wetscher et al., 1995b; Wetscher et al., 1995c). ROS contributes to esophageal inflammation, and ROS produced by inflammatory and epithelial cells accelerate RE resulting in Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma (Abdel-Latif et al., 2009). Thus, therapeutic agents possessing the properties to scavenge ROS and modulate inflammatory response might exert significant effects in attenuating tissue injury by RE.

The application of natural products that regulate redox state and inflammation has emerged for GERD treatment. For example, an ethanol extract of Artemisia asiatica was reported to prevent RE through its antioxidant properties in vivo, (Oh et al., 2001b) and a phytopharmaceutical derived from A. asiatica has been prescribed for gastritis patients in S. Korea (Seol et al., 2004). Chlorogenic acid (CGA), formed by the esterification of caffeic acid and quinic acid, is one of the most abundant polyphenols in the human diet (Feng et al., 2005; Cha et al., 2014). Numerous studies based on in vivo and in vitro experiments show that CGA has antioxidant, antibacterial and anti-carcinogenic activities (Belkaid et al., 2006; Sato et al., 2011). Moreover, we previously reported the protective effects of CGA against experimental inflammatory disorders: CGA inhibited high mobility group box 1 release and toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathways in liver during both septic and ischemic insult, suggesting its potential in immunomodulation (Lee et al., 2012; Yun et al., 2012). Most recently, CGA was shown to suppress HCl/ethanol- and piroxicam-induced gastric mucosal injury (Shimoyama et al., 2013) while its high absorption capacity to gastric and intestinal cells by oral route is focused (Farah et al., 2008; Stalmach et al., 2010). However, the effects of CGA on RE have not been studied.

In this study, we investigate the protective effects and molecular mechanisms of CGA in a surgically-induced rat model of RE, with particular attention to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies

CGA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The following antibodies were used in this study: inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA, USA), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Animals

All animals received care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care formulated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No.86-23, revised 1985) and the guidelines of the Sungkyunkwan University Animal Care Committee. Male SD rats weighing 180 to 200 g were obtained from Orient Bio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea) and were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for at least one week. Rats were maintained in a room with controlled temperature and humidity (25 ± 1°C and 55 ± 5%, respectively) with a 12 h light-dark cycle.

RE induction and drug treatment

All rats were fasted for 24 h prior to surgical procedures, but were provided with tap water ad libitum. Surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia, which was accomplished by intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (55 mg/kg) and xylazine (7 mg/kg). The pyloric stenosis model (Omura et al., 1999) was used, and the duodenum near the pylorous was wrapped with a piece of Nélaton catheter (width, 3.0 mm; Camel®, Dae Bo Co., GwangJu, Korea) as a ring. The diameter of each Nélaton catheter was 4.0 mm and the ring was surrounded and tied with 3-0 silk thread to prevent dislodgement. The transitional region between the forestomach and the glandular portion (the limiting ridge) was ligated with 3-0 silk thread. The sham operation induced a midline laparotomy alone without further surgical interventions. After preparation of the model, the animals were deprived of food for 48 h but were allowed free access to drinking water. Two days after the surgery, vehicle or drugs were administered for 12 days. After the final treatment, rats were fasted for 24 h and sacrificed. The entire esophagus was removed and examined for gross mucosal injury. The esophageal tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for the biochemical assays.

Experimental groups

All drugs were administered orally. Rats were divided into 6 groups as follows (n=8–10 rats per group). Group I: vehicle-treated sham animals (sham); Group II: vehicle-treated RE animals (control); Group III-V: CGA 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg (dissolved in saline)-treated RE animals (CGA 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg); Group VI: omeprazole 10 mg/kg (dissolved in 0.5% methylcellulose (MC)-distilled water (DW))-treated RE animals (Omp 10 mg/kg). In vehicle-treated rats, saline or 0.5% MC-DW was administered in the same volume and manner as the respective reagents. No effects of these vehicles on esophagus function were detected. The dose range of the drugs and the time of administration were chosen based on previous reports (Miwa et al., 2009; Shimoyama et al., 2013) and our preliminary studies.

Esophageal lesion score

The esophageal tissues were washed with physiological saline and photographs were taken of specified areas of damage. The width of the damaged esophagitis area (mm2) was determined and defined as the lesion score.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Formalin-fixed samples were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and slides were assessed for inflammation and tissue damage using Olympus microscopes (OLYMPUS OPTICAL Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 200× magnification.

Gastric content pH

The gastric contents were obtained from the stomach and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was assessed for pH (Toledo 320, Mettler, Switzerland).

Lipid peroxidation and GSH/GSSG ratio

The steady-state level of malondialdehyde (MDA), which is the end-product of lipid peroxidation, was determined in the esophageal tissues by measuring the levels of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (Buege and Aust, 1978). The total esophageal glutathione level was determined by measuring yeast-glutathione reductase, 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) in the esophagus homogenates after precipitation with 1% picric acid. The level of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) was determined using the same method but in the presence of 2-vinylpyridine. The reduced glutathione (GSH) level was calculated as the difference between the total glutathione and the GSSG level (Griffith, 1980).

Serum TNF-α

The serum TNF-α level was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercial TNF-α ELISA assay kit (BD Biosciences Co., SanJose, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis for iNOS and COX-2

Esophageal tissue protein lysates were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, separated on SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes as previously described (Tuan et al., 2013). Western blotting was performed using primary antibodies and horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies suitable for each parameter. The WEST-one Western Blot Detection System (iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., Seongnam, Korea) was used for detection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Intensities of the immunoreactive bands were determined using TotalLab TL120 software (IVDLab Nonlinear Dynamics Co. Ltd., Newcastle, UK). β-Actin was used as a loading control and the levels of proteins were normalized with respect to β-actin band intensity.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. The overall significance of the data was tested by one-way analysis of variance using the SPSS v.12.0 statistical software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at p<0.05 with appropriate Bonferroni corrections made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Esophageal lesion scores

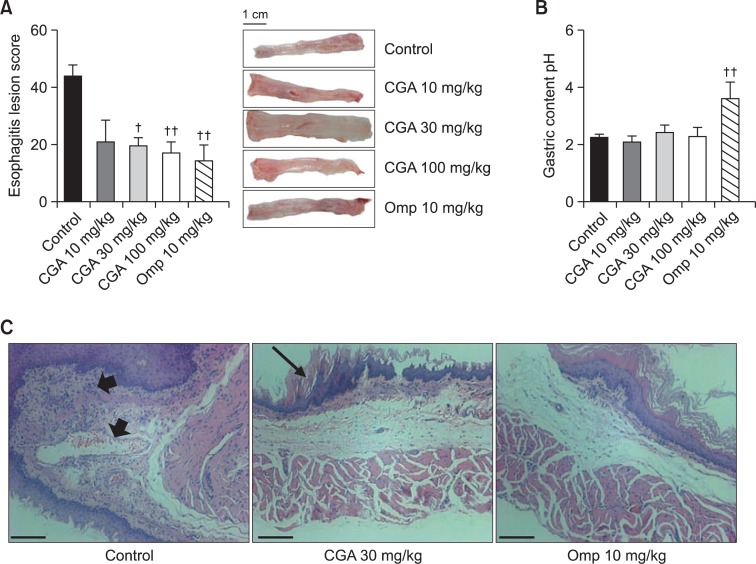

Sham-operated rats showed normal esophageal tissue. The esophageal lesion score (mm2) of the RE control group was 44.2 ± 3.6. CGA at 10 mg/kg showed a tendency to attenuate the lesion score to 20.9 ± 7.7. CGA at 30 and 100 mg/kg attenuated the lesion score to 19.6 ± 2.8 and 17.0 ± 3.9, respectively. Omeprazole at 10 mg/kg also attenuated the lesion score to 14.4 ± 5.5 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Effects of CGA on esophageal damage, gastric content pH and histological observations in RE. (A) The esophageal lesion score was determined by the width of the damaged esophagitis area (mm2). Scale bar, 1 cm. (B) The pH of the gastric contents from the stomach was measured. (C) Representative photomicrographs of H&E stained sections are shown (original magnification×200). RE control animals showed inflammatory cell infiltrations and edema (arrows heads); CGA 30 mg/kg- and omeprazole 10 mg/kg-treated RE animals showed attenuation of pathological changes. Arrow indicates mild thickening of the esophageal epithelium. Scale bar, 50 μm. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of 8–10 animals per group. †,††Denote significant differences (p<0.05, p<0.01), compared with the control group.

Gastric content pH

The gastric content pH of the RE control group was 2.2 ± 0.1, which was similar to that of sham-operated rats. CGA at 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg did not affect the gastric content pH (2.1 ± 0.2, 2.4 ± 0.3, and 2.2 ± 0.3, respectively). However, omeprazole at 10 mg/kg increased the pH to 3.6 ± 0.6 (Fig. 1B).

Histological observations

The representative pathological observations are shown in Fig. 1C. After RE induction, severe inflammatory cell infiltrations with large excavated ulcerations were observed. Moreover, RE caused marked thickening of the esophageal epithelium, elongation of lamina propria papillae and basal cell hyperplasia. However, both CGA at 30 mg/kg and omeprazole at 10 mg/kg attenuated these changes.

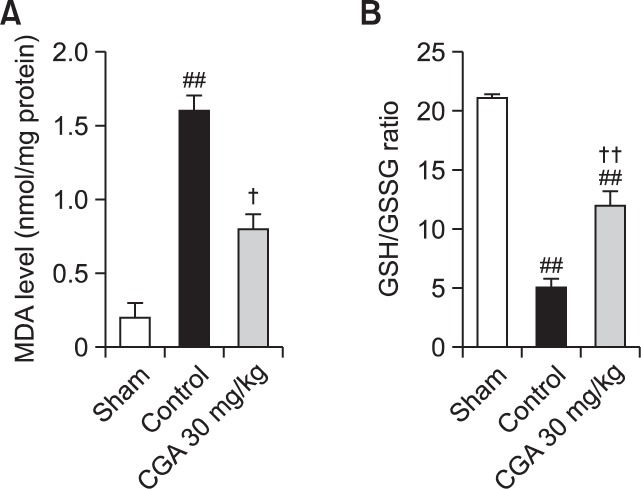

Lipid peroxidation and GSH/GSSG ratio

In the sham group, the level of MDA was 0.2 ± 0.1 nmol/mg protein. Following RE treatment, the level of MDA increased significantly, to 1.6 ± 0.1 nmol/mg protein, compared with the sham. CGA at a concentration of 30 mg/kg was found to attenuate this increase in MDA level (0.8 ± 0.1 nmol/mg protein). The GSH/GSSG ratio in the sham group was 21.1 ± 0.3. After RE treatment, the GSH/GSSG ratio significantly decreased to 5.1 ± 0.7, and this decrease was attenuated by 30 mg/kg of CGA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effects of CGA on oxidative stress in RE. The level of MDA (A), a marker of lipid peroxidation, and GSH/GSSG ratio (B) were respectively measured in esophageal tissue. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of 8–10 animals per group. ##Denotes significant differences (p<0.05, p<0.01), compared with the sham group; †,††De note significant differences (p<0.05, p<0.01), compared with the control group.

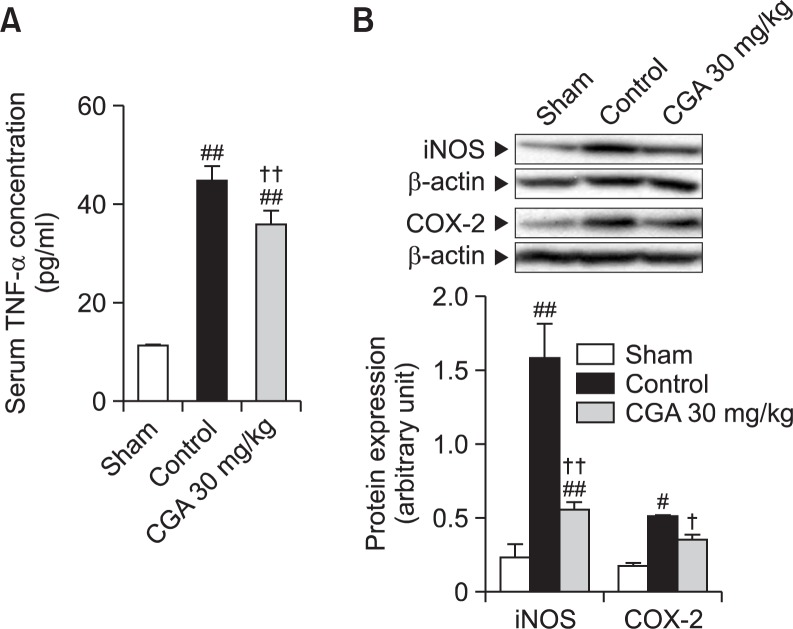

Serum TNF-α concentration

The serum level of TNF-α in the sham group was 11.3 ± 0.2 pg/ml. After RE treatment, the serum level of TNF-α significantly increased to 44.9 ± 2.8 pg/ml, and CGA at 30 mg/kg attenuated this increase (35.9 ± 2.8 pg/ml)(Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effects of CGA on inflammatory mediators in RE. (A) The serum concentration of TNF-α was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) Western blot analysis for iNOS and COX-2 was performed on whole extracts from the esophagus. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of 8–10 animals per group. #,##Denote significant differences (p<0.05, p<0.01), compared with the sham group; †,††Denote significant differences (p<0.05, p<0.01), compared with the control group.

iNOS and COX-2 protein expressions

The levels of iNOS and COX-2 protein expression significantly increased to 6.9 and 3.0 times the sham value after RE treatment. CGA at 30 mg/kg attenuated these increases, respectively (Fig. 3B).

DISCUSSION

A number of pathological mechanisms have been suggested to play roles in RE, including hypersensitivity of the esophageal mucosal to physiological reflux, reduced mucosal defense mechanisms, and gastric motility disturbances. A recent study reported that mucosal damage detected in GERD might result from the release of inflammatory mediators from mucosal and sub-mucosal cells in response to bile salts and gastric refluxate (Souza et al., 2009). Since GERD is a multi-factorial disease, it would be plausible to use multi-target drugs for its treatment, and the objective of the treatment should be to restore the balance between aggressive and mucosal protecting factors, rather than simple acid suppression.

Insight into RE treatment has shifted toward studies aimed at the understanding of antioxidant and cytoprotective actions of natural products or bioactive components in the diet. Previously, Flos Lonicerae extract, which contains CGA as a major component, increased the activities of endogenous antioxidants including GSH, superoxide dismutase and catalase, and ultimately reduced esophageal damage induced by RE (Ku et al., 2009). CGA, a phenolic compound with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokines release in RAW264.7 cells (Shan et al., 2009). Most recently, CGA inhibited neutrophil migration and restored the levels of antioxidant enzymes in ethanol/HCl- and piroxicam-induced gastric ulcer models, suggesting protective effects against gastrointestinal tract inflammation (Shimoyama et al., 2013). However, the effects and precise mechanisms of CGA in RE have not been studied until now.

Exposure of the esophagus to acid and digestive enzymes found in gastric fluid or duodenal contents regurgitated into the stomach may induce and promote irritation and result in symptoms and morphological changes to the esophageal mucosa (Oh et al., 2001a). In the present study, esophagitis was found 2 or 3 cm above the esophagogastric junction, and esophageal lesion scores were remarkable 14 days after RE operation. However, the administration of CGA attenuated the lesion score, suggesting the therapeutic potential of CGA against RE. As typical reflux symptoms are associated with reflux episodes with drops in pH, lower minimum pH and reduced acid clearance times (Bredenoord et al., 2006), we measured the pH of gastric contents. Unexpectedly, CGA did not affect pH level, while omeprazole, an irreversible inhibitor of H+, K+-ATPase, showed strong effects on gastric content pH, confirming its anti-secretory effects. Our results agree with those of a previous report indicating that CGA does not interfere with gastric secretion or the pH of gastric juices in mice with pyloric ligatures (Shimoyama et al., 2013). Moreover, this characteristic of CGA might supplement the side effects of long term treatment of PPI such as hypochlorhydria or rebound hypersecretion that could lead to PPI-deficiency (Reimer et al., 2009).

Inflammatory processes seem to play pivotal roles in the underlying mechanisms of the symptoms and pathogenesis of gastrointestinal conditions including GERD. Particularly in the chronic phase of RE, continuous exposure to acid induces persistent infiltration of inflammatory cells and increases epithelial cell proliferation in the basal layer (Ismail-Beigi et al., 1970). Increased TNF-α and interleukin-6 concentrations have been demonstrated in the esophageal tissues of rats challenged to produce acute RE (Cheng et al., 2005a; Cheng et al., 2005b). iNOS, an enzyme catalyzing NO production, is also upregulated during the development of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma, and its expression may be stimulated by cytokines such as TNF-α during mucosal inflammation and tumor progression (Wilson et al., 1998). In addition, COX-2 producing PGE2 were colocalized in epithelial cells of the basal layer, as well as inflammatory and mesenchymal cells in the lamina propria and submucosa exposed to acid re-flux. COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib significantly reduced the severity of chronic esophagitis (Hayakawa et al., 2006). Nuclear factor-kappa B, mitogen-activated protein kinases and protein kinase C activation are known to be involved in the regulation of acid-induced upregulation of these inflammatory mediators in vitro (Rafiee et al., 2009). In the present study, serum levels of TNF-α and iNOS and COX-2 protein expressions in esophageal tissues were increased by RE, and CGA attenuated these increases. These results indicate that the esophagoprotection by CGA might be attributable to its anti-inflammatory properties.

Oxygen-derived free radicals in RE induced esophageal mucosal damage resulting in mucosal inflammation and to control free radical generation, such as superoxide dismutase administration, inhibited the incidence of RE (Wetscher et al., 1995a). Increased production of oxygen-derived free radicals was accompanied by enhanced esophageal mucosal lipid peroxidation, which is a sensitive marker of membrane damage caused by free radicals (Farhadi et al., 2002). This is evident from our results showing significant increases in the levels of lipid peroxidation in RE rats. In addition, thiol containing glutathione is an important non-enzymatic antioxidant, which promotes several toxic metabolites. The gastric mucosa contains high amounts of glutathione, which is vital for the maintenance of mucosal integrity, since depletion of GSH from the gastric mucosa by electrophilic compounds induces mucosal ulceration (Maity et al., 1998). Exogenous thiol compounds have been suggested to protect the stomach from ethanol-induced necrosis (Robert et al., 1984). In the present study, decreases in the GSH/GSSG ratio were observed in RE-induced rats. CGA not only inhibited lipid peroxidation but increased the GSH/GSSG ratio. In summary, our results signify that CGA could act not only as a direct free radical scavenger but also enhance esophageal defense mechanisms to minimize esophageal inflammation.

In conclusion, CGA promotes regression of RE through the down-regulation of inflammatory response, possibly due to its antioxidant capacity. CGA can serve as an alternative treatment and/or in combination with the anti-secretory regimen to alleviate the severity of RE.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST; 2012R1A5A2A28671860). Jung-Woo Kang (2011-0006724) received ‘Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program’ support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST).

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Latif MM, Duggan S, Reynolds JV, Kelleher D. Inflammation and esophageal carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid A, Currie JC, Desgagnes J, Annabi B. The chemopreventive properties of chlorogenic acid reveal a potential new role for the microsomal glucose-6-phosphate translocase in brain tumor progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Curvers WL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Determinants of perception of heartburn and regurgitation. Gut. 2006;55:313–318. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buege JA, Aust SD. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JW, Piao MJ, Kim KC, Yao CW, Zheng J, Kim SM, Hyun CL, Ahn YS, Hyun JW. The polyphenol chlorogenic acid attenuates UVB-mediated oxidative stress in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Biomol Ther. 2014;22:136–142. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Cao W, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. Inflammation induced changes in arachidonic acid metabolism in cat LES circular muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005a;288:G787–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00327.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Cao W, Fiocchi C, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. Platelet-activating factor and prostaglandin E2 impair esophageal ACh release in experimental esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005b;289:G418–428. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah A, Monteiro M, Donangelo CM, Lafay S. Chlorogenic acids from green coffee extract are highly bioavailable in humans. J Nutr. 2008;138:2309–2315. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.095554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhadi A, Fields J, Banan A, Keshavarzian A. Reactive oxygen species: are they involved in the pathogenesis of GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, and the latter’s progression toward esophageal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Lu Y, Bowman LL, Qian Y, Castranova V, Ding M. Inhibition of activator protein-1, NF-kappaB, and MAPKs and induction of phase 2 detoxifying enzyme activity by chlorogenic acid. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27888–27895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith OW. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem. 1980;106:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Fujiwara Y, Hamaguchi M, Sugawa T, Okuyama M, Sasaki E, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Higuchi K, Arakawa T. Roles of cyclooxygenase 2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 in rat acid reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 2006;55:450–456. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail-Beigi F, Horton PF, Pope CE., 2nd Histological consequences of gastroesophageal reflux in man. Gastroenterology. 1970;58:163–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz PO. Optimizing medical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: state of the art. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003;3:59–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku SK, Seo BI, Park JH, Park GY, Seo YB, Kim JS, Lee HS, Roh SS. Effect of Lonicerae Flos extracts on reflux esophagitis with antioxidant activity. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4799–4805. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Yoon SJ, Lee SM. Chlorogenic acid attenuates high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and enhances host defense mechanisms in murine sepsis. Mol Med. 2012;18:1437–1448. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity S, Vedasiromoni JR, Ganguly DK. Role of glutathione in the antiulcer effect of hot water extract of black tea (Camellia sinensis) Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;78:285–292. doi: 10.1254/jjp.78.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa H, Oshima T, Sakurai J, Tomita T, Matsumoto T, Iizuka S, Koseki J. Experimental oesophagitis in the rat is associated with decreased voluntary movement. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:296–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh TY, Lee JS, Ahn BO, Cho H, Kim WB, Kim YB, Surh YJ, Cho SW, Hahm KB. Oxidative damages are critical in pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis: implication of antioxidants in its treatment. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001a;30:905–915. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh TY, Lee JS, Ahn BO, Cho H, Kim WB, Kim YB, Surh YJ, Cho SW, Lee KM, Hahm KB. Oxidative stress is more important than acid in the pathogenesis of reflux oesophagitis in rats. Gut. 2001b;49:364–371. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura N, Kashiwagi H, Chen G, Suzuki Y, Yano F, Aoki T. Establishment of surgically induced chronic acid reflux esophagitis in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:948–953. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee P, Nelson VM, Manley S, Wellner M, Floer M, Binion DG, Shaker R. Effect of curcumin on acidic pH-induced expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in human esophageal epithelial cells (HET-1A): role of PKC, MAPKs, and NF-kappaB. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G388–398. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90428.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer C, Sondergaard B, Hilsted L, Bytzer P. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:80–87. 87 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A, Eberle D, Kaplowitz N. Role of glutathione in gastric mucosal cytoprotection. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:G296–304. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.247.3.G296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Itagaki S, Kurokawa T, Ogura J, Kobayashi M, Hirano T, Sugawara M, Iseki K. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant properties of chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid. Int J Pharm. 2011;403:136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol SY, Kim MH, Ryu JS, Choi MG, Shin DW, Ahn BO. DA-9601 for erosive gastritis: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2379–2382. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan J, Fu J, Zhao Z, Kong X, Huang H, Luo L, Yin Z. Chlorogenic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in RAW264.7 cells through suppressing NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:1042–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama AT, Santin JR, Machado ID, de Oliveira e Silva AM, de Melo IL, Mancini-Filho J, Farsky SH. Antiulcerogenic activity of chlorogenic acid in different models of gastric ulcer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2013;386:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, Schuler CM, Carmack SW, Zhang HY, Zhang X, Yu C, Hormi-Carver K, Genta RM, Spechler SJ. Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1776–1784. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalmach A, Steiling H, Williamson G, Crozier A. Bio-availability of chlorogenic acids following acute ingestion of coffee by humans with an ileostomy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuan PA, Thwe AA, Kim YB, Kim JK, Kim SJ, Lee S, Chung SO, Park SU. Effects of white, blue, and red light-emitting diodes on carotenoid biosynthetic gene expression levels and carotenoid accumulation in sprouts of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum Gaertn.) J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:12356–12361. doi: 10.1021/jf4039937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetscher GJ, Hinder PR, Bagchi D, Perdikis G, Redmond EJ, Glaser K, Adrian TE, Hinder RA. Free radical scavengers prevent reflux esophagitis in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1995a;40:1292–1296. doi: 10.1007/BF02065541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetscher GJ, Hinder RA, Bagchi D, Hinder PR, Bagchi M, Perdikis G, McGinn T. Reflux esophagitis in humans is mediated by oxygen-derived free radicals. Am J Surg. 1995b;170:552–556. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetscher GJ, Perdikis G, Kretchmar DH, Stinson RG, Bagchi D, Redmond EJ, Adrian TE, Hinder RA. Esophagitis in Sprague-Dawley rats is mediated by free radicals. Dig Dis Sci. 1995c;40:1297–1305. doi: 10.1007/BF02065542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KT, Fu S, Ramanujam KS, Meltzer SJ. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in Barrett’s esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2929–2934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun N, Kang JW, Lee SM. Protective effects of chlorogenic acid against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat liver: molecular evidence of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]