Abstract

The growing population of long-term survivors of childhood cancer in the United States estimated in 2009 to be nearly 330,000 mandates familiarity with imaging findings that may be related to prior disease, therapy and toxicities. More than 24% of these patients have survived more than 30 years from the time of diagnosis of their malignancy. Thus, imagers of adult as well as pediatric patients should be cognizant of findings seen in this patient cohort. This image-based review will discuss findings demonstrated on chest radiographs that may suggest that the imaged patient is a childhood cancer survivor.

Introduction

Advances in the detection, treatment and supportive care of pediatric malignancies has allowed for improved long term survival among childhood cancer survivors. At present, the 5 year survival for those diagnosed with a pediatric malignancy exceeds 80% with a 10-year survival rate of 75% [1]. The increasing number of adult survivors of childhood malignancies now approaches an estimated 360,000 individuals, allowing for more extensive studies of the delayed manifestations of adverse effects related to cancer treatment [1, 2]. Medical conditions that persist or present in 5 or more years following treatment are referred to as late effects. Studies that investigate the late effects of pediatric cancer treatment have shown that 73.4% of survivors will experience a chronic medical condition, with over 40% experiencing a serious or life-threatening problem [3].

The manifestation of late effects are wide ranging and involve all organ systems, with differential presentation largely dependent on both the primary malignancy and the treatment received. Some of the most common late effects observed in childhood cancer survivors are pulmonary and cardiac complications with skeletal complications and secondary malignancies being less common [4]. The increased survivorship and incidence of morbidity amongst those treated for childhood malignancies necessitates increased vigilance on part of the adult survivors’ health-care providers to both detect and treat the anticipatory late effects in this population. The manifestation of tissue injury from therapy administered during childhood may not become apparent until the patient enters a phase of rapid growth such as adolescence. At such times, the treatment insult on normal tissues may result in impaired growth [5]. Diagnostic imaging can provide a robust means through which many late effects can be detected. The aim of this article is to provide an overview of selected radiographic manifestations of thoracic findings that may be associated with previous treatment for pediatric cancers and late effects by providing an image-based approach to identifying unique radiographic characteristics that may be seen on chest radiographs obtained for reasons unrelated to a history of previous childhood cancer. The risk factors for and prevalence of tumor recurrence and secondary malignant neoplasms are well-described in the literature and will not be included in this pictorial.

Residual mediastinal mass after treatment for lymphoma

The presence of residual abnormality of the mediastinum or hila after completion of therapy for lymphoma can induce anxiety in patients, parents and healthcare providers. Approximately two-thirds of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and one-third of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have been reported to have residual mediastinal masses after completion of therapy [6] which can be apparent on chest radiographs [Figure 1]. These residual masses more often occur in patients presenting with bulky mediastinal disease [7] or those with nodular sclerosing subtype of Hodgkin’s disease [8]. The residual soft tissue masses are usually of benign fibrotic or inflammatory tissue and may be seen in up to 41% of chest radiographs pediatric patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease and 46% of chest CTs [9]; these masses may calcify [Figure 2].

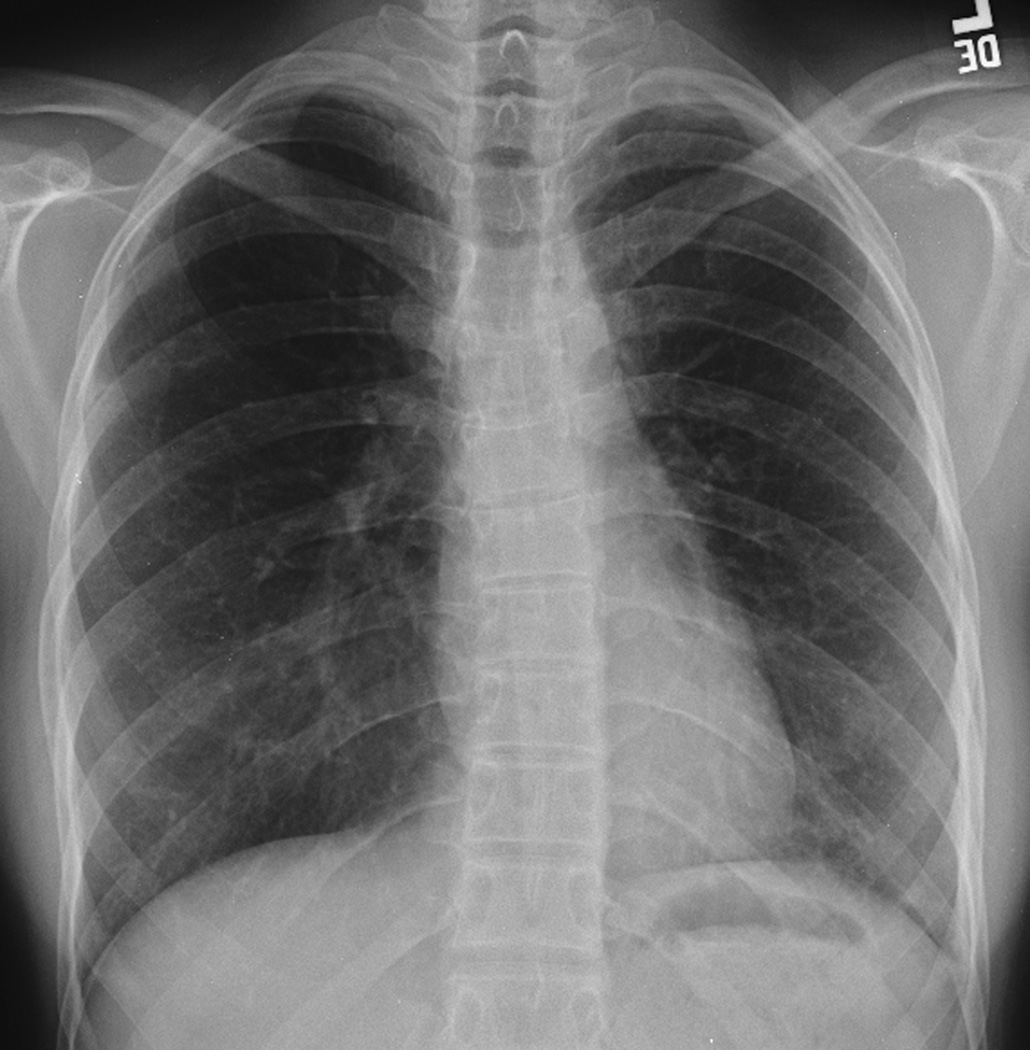

Figure 1. Residual post-therapy mediastinal mass.

18-year-old man diagnosed with Stage IV B nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease was treated with chemotherapy and 2550cGy mantle and 800 cGy whole lung irradiation. Residual mediastinal mass persisted over the subsequent 8 years from initial imaging at diagnosis through follow-up.

A. Posteroanterior chest radiograph at the time of diagnosis shows a large anterior mediastinal mass which extends bilaterally from the midline.

B and C. A follow-up posteroanterior chest radiograph obtained 8 years from diagnosis shows residual superior mediastinal widening that corresponds to the residual masses shown on the corresponding computed tomography image, C.

Figure 2. Calcification of residual mediastinal mass.

24-year-old survivor of Stage IIIB nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease diagnosed at the age of 15-years. His disease was refractory to standard chemotherapy prompting autologous bone marrow transplantation and 2100 cGy mediastinal radiation.

A and B. A, posteroanterior and, B, lateral chest radiographs at diagnosis show a bulky anterior mediastinal mass extending through the thoracic inlet on the right, into the right neck.

C. C, Follow-up posteroanterior chest radiograph 6 years later show significant reduction in the mediastinal mass with development of dense calcifications.

Particularly in pediatric patients, thymic rebound, developing after completion of therapy, may mimic a residual mass [8]. Comparison with prior chest imaging can resolve whether or not the mass has changed in size and contour. Typically, residual fibrotic masses continue to regress over time [7, 8]. However, increase in the residual mass or new adenopathy warrants further evaluation for the possibility of recurrent disease [Figure 3]. Such can be accomplished using MR [10, 11] or CT for anatomic characterization of changes seen on chest radiographs [6]. However, MR and CT have limited ability to differentiate between active disease and fibrosis or scarring [9–13]. Thus, 18F-FDG PET/PET-CT may be used to assess for metabolic activity (having largely replaced 67Gallium imaging) that may indicate disease relapse [6, 13].

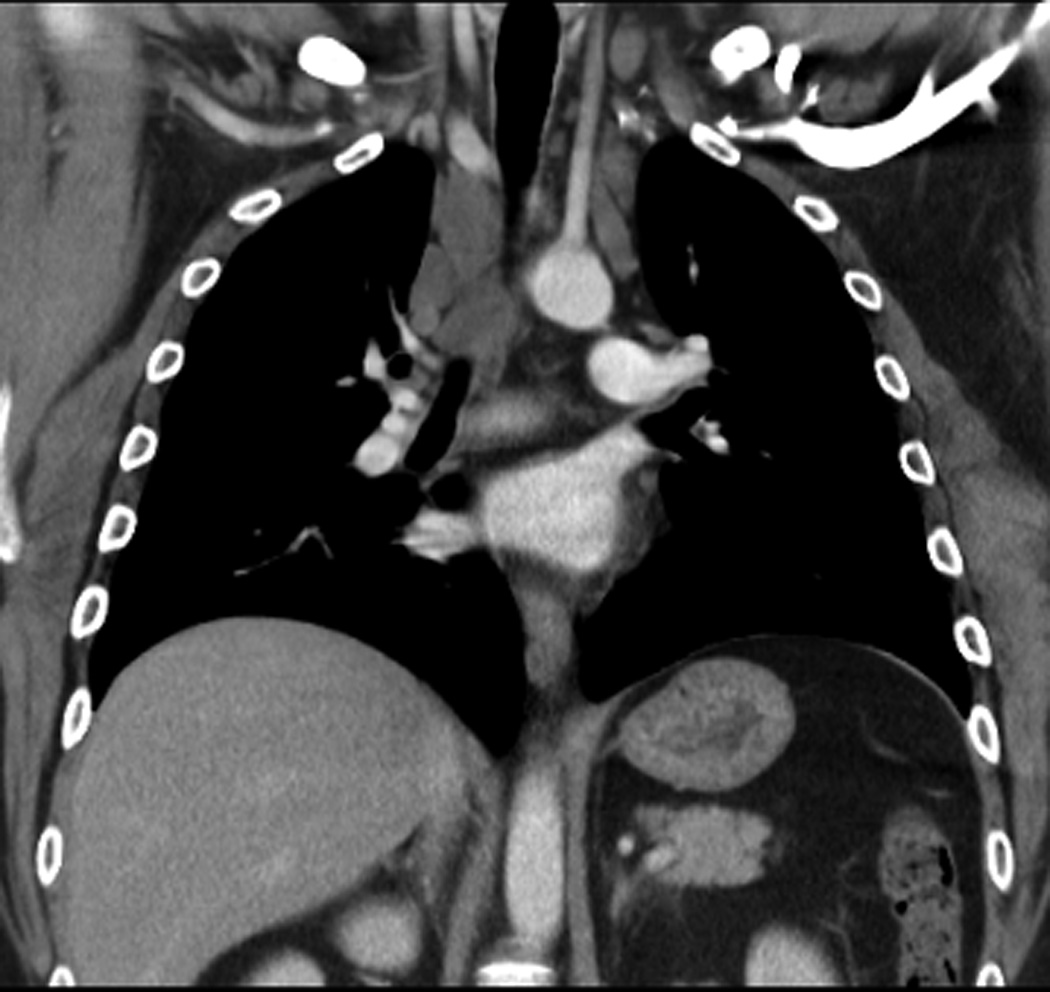

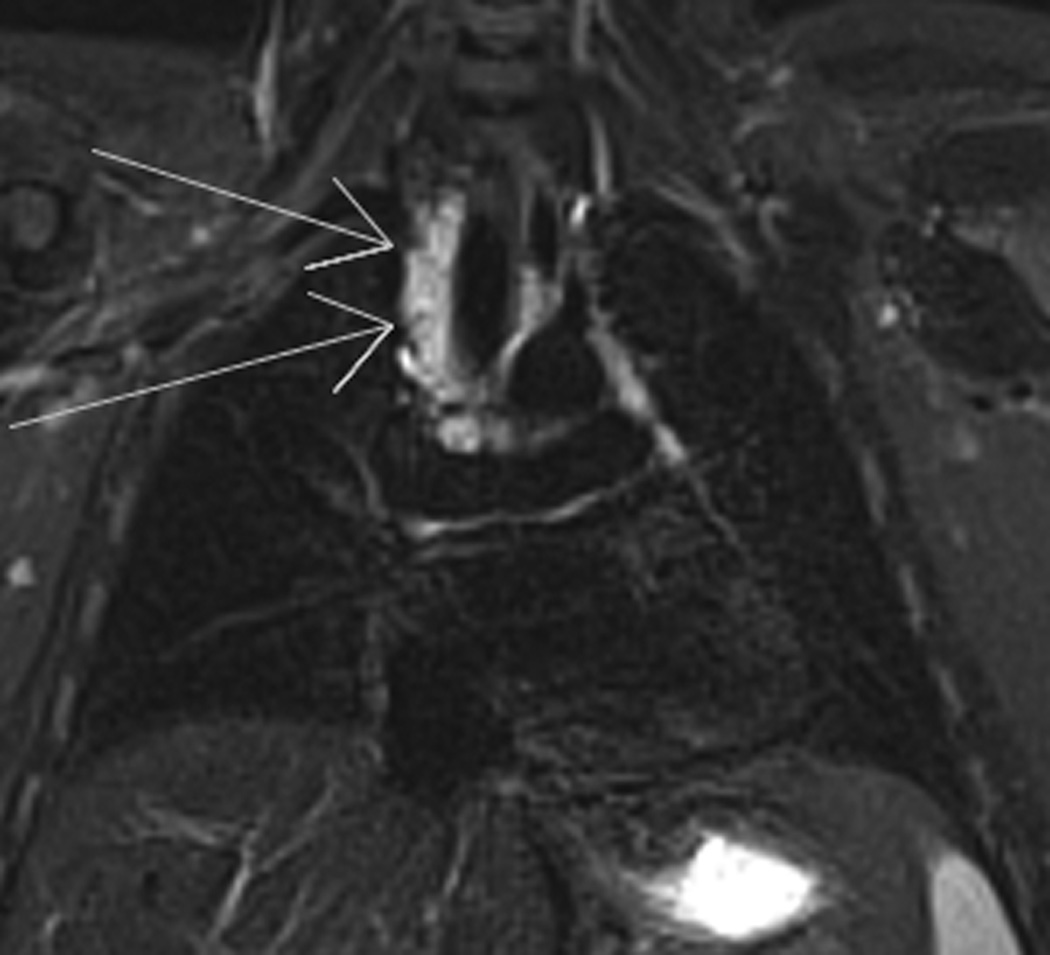

Figure 3. Relapse lymphoma.

9-year-old boy diagnosed with Stage IA Hodgkin’s disease right neck achieved complete remission with chemotherapy. At routine follow-up 3.5 years later, left hilar relapse was suspected.

A. and B. A, posteroanterior and lateral, B, chest radiographs show stable post-therapy appearance of the thoracic structures.

C. and D. Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows slight increased density left hilum which, on the lateral view, D, is shown to represent an ovoid nodule (lines).

E., and F., E, axial non-contrast T1- and, F, T2-weighted images of the chest show right paratracheal (long arrows), left hilar and subcarinal (short arrows) adenopathy consistent with disease relapse.

Pulmonary complications

The lungs are one of the most radiation- and chemo-sensitive organs in the body [14]. Functional compromise arising from radiation is compounded by chemotherapy-induced toxicities all of which may progress from initial injury to pulmonary interstitium over time to pulmonary fibrosis [14]. Pulmonary complications after therapy for childhood cancer include pulmonary fibrosis [Figure 4], chronic cough, recurrent pneumonia, use of supplemental oxygen and pleurisy. Mertens et al, reporting on the prevalence of self-reported pulmonary complications from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, found chest radiation was statistically associated with all of these adverse late effects as were various chemotherapeutic agents [14]. Chemotherapeutic agents associated with development of pulmonary insufficiency include busulfan, carmustine [14, 15], cyclophosphamide, lomustine and bleomycin [15]. At 20 years from diagnosis of the primary malignancy, a 3.5% cumulative incidence of pulmonary fibrosis was associated with chest radiation [14] and results from injury to type II pneumocytes and endothelial cells [5, 16]. Chronic pulmonary impairment results from compromise of alveolar growth and generation of new alveoli [5]. Radiographic findings of fibrosis include pleural thickening, regional or focal pulmonary contraction, linear scarring and streaking that may extend beyond the distribution of radiation portals [5].

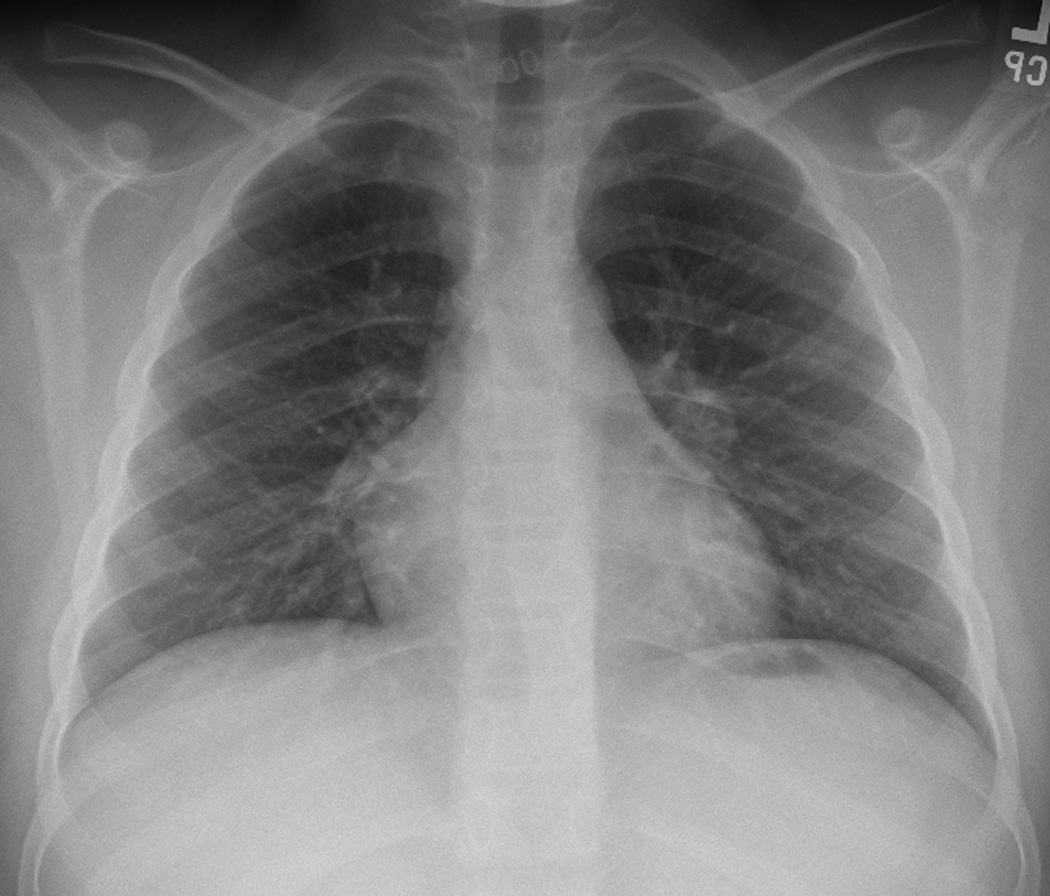

Figure 4. Progressive radiation fibrosis.

19-year-old woman diagnosed with Stage IIA nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease was treated with chemotherapy and 2550 cGy modified mantle irradiation. One year after completing therapy, she developed disease relapse treated with intensive chemotherapy, autologous stem cell rescue and radiation therapy to the lower cervical spine and porta hepatis.

A. At diagnosis, the posteroanterior chest radiograph showed right paratracheal adenopathy and bilateral superior mediastinal widening, which improved with therapy.

B. By 3-years later, straightening of the left mediastinum and early cephalad retraction of the left hilum is noted.

C. Progression of cephalad retraction of the left hilum, coarsening of post-radiation scarring at 11 years, D, from diagnosis are evident and progressed in parallel with decreasing pulmonary function, ultimately leading to her demise.

The likelihood and severity of development of these complications is dependent on dose of radiation and chemotherapy, younger patient age at the time of therapy, smoking [17]. Decrease in pulmonary function longitudinally declines after therapy [18] and may compound the decrease in pulmonary function normally seen with aging [19]. Further, chemotherapy, surgery and bone marrow transplantation may compound the effects of radiation therapy [20].

Cardiomyopathy

An increased risk for cardiovascular disease is seen in survivors of childhood cancer treated with radiation therapy or chemotherapy, independently or in combination, and represents a cause of cardiac morbidity and mortality [21]. Risk factors particularly identified to increase the likelihood of developing anthracycline-associated cardiovascular toxicity include age younger than 5 years at the time of treatment, female sex, cumulative doses of 300 mg/m2 or greater, cardiac irradiation of 3000 cGy or more, and chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy [22, 23]. In addition, Orgel et al recently reported that an elevated body mass index and Hispanic ethnicity are also independent risk factors for the development of declining left ventricular shortening fraction in anthracycline-based therapy for acute myeloid leukemia [24]. Other reported risk factors include black race and the presence of trisomy 21 [25].

The most common cardiac event reported is congestive heart failure [26]. The hallmark of anthracycline cardiotoxicity is reduced thickness and mass of the left ventricular wall [27]. Though symptomatic cardiac compromise is infrequent [22, 23], a recent study reported a 12.6% incidence of such events in patients treated with both anthracyclines and cardiac irradiation, 7.3% incidence with anthracyclines alone and 4.0% incidence after cardiac irradiation with a median patient age of 27 years at the time of the events [26] [Figure 5]. Cardiotoxic effects of therapy may not manifest until adulthood or during times of stress such as pregnancy or physical exertion [22].

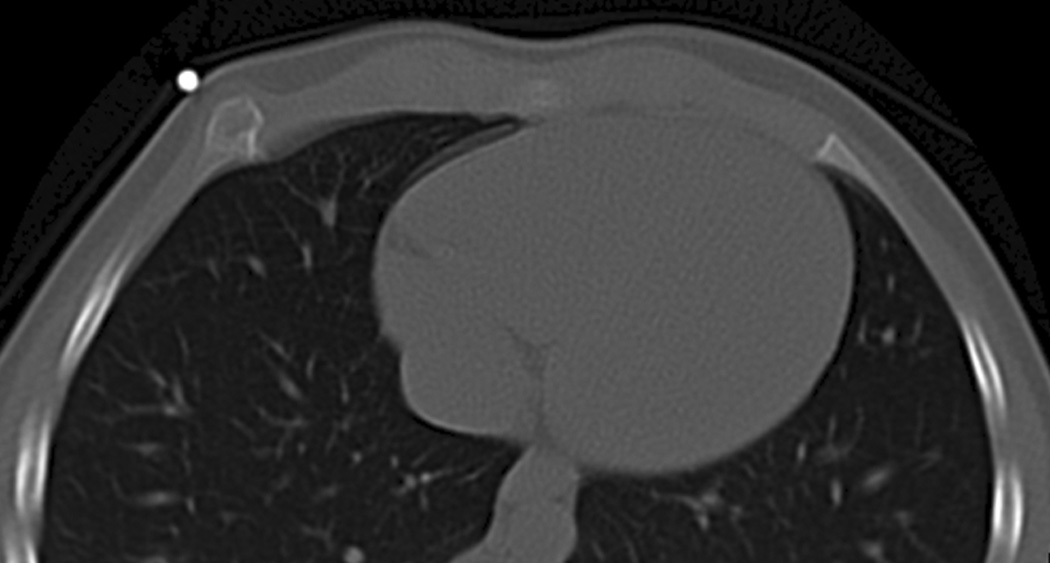

Figure 5. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy.

This 12-year-old patient was diagnosed with nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease and received multiagent chemotherapy that included anthracycline. Pathologic examination revealed Grade 2 of 3 anthracycline cardiac toxicity.

A. Posteroanterior chest radiograph obtained about 1 year after completion of therapy demonstrate cardiomegaly, bilateral pleural effusions and pulmonary vascular congestion indicative of congestive heart failure.

A recent investigation of 62 adolescent survivors of childhood cancer (mean age 14.6 years at the time of study) who received anthracyclines as part of their oncotherapy, found that gadolinium-enhanced cardiac MR detected and quantified both left and right ventricular dysfunction in 61% and 27%, respectively [28].

Breast hypoplasia

Breast hypoplasia or aplasia following irradiation to the chest during childhood is a well-known late effect [Figure 6]. Radiation-induced underdevelopment of the breast has been reported in a variety of pathologies for which irradiation has been used including cutaneous hemangiomas of the chest [29], mediastinal lymphadenopathy [30], Wilm’s tumor [31, 32] and neuroblastoma [32]. Radiation effects on developing human breast tissue is dose dependent [30, 33] and may occur with doses of < 500 cGy [34]. Clinical changes associated with radiation-induced breast underdevelopment include the presence of dyschromasia and telengiectasias on the affected breast and overall asymmetric breast development with the irradiated breast being smaller and irregular in size compared to the non-irradiated breast [33]. Reported histopathological findings of irradiated hypoplastic breasts report extensive fibrosis, loss of breast lobules and significant shrinkage of the ducts [33]. Patients affected by breast hypoplasia can also experience significant psychological distress due to the undesirable cosmetic effects of asynchronous breast growth [33].

Figure 6. Breast hypoplasia.

This 49-year-old woman was diagnosed with Wilm’s tumor at age 5 years and received 1200 cGy whole lung irradiation for pulmonary metastases as well as 1200cGy abdominal radiation therapy for primary disease and hepatic metastases.

A. and B. A., posteroanterior and lateral, B., chest radiographs demonstrate hypoplasia of both breasts. The anteroposterior diameter of the chest is narrow from radiation-induced rib dysplasia.

It is important to recognize the association of breast cancer arising as a result of irradiation that included breast tissue [35]. After chest irradiation, the standardized incidence ratios for developing secondary breast cancer were 24.7 (95%CI 18.3–31.0) as opposed to those who received no chest irradiation being 4.8 (95%CI 2.9 – 7.4)[35]. Thus, education of these patients toward health risks associated with chest irradiation should be prompted by recognition of this finding upon verification of prior therapy.

Skeletal sequelae

Radiation-induced changes of bone have been recognized for decades; any bone exposed to the radiation field can be affected. Therapy inflicted during the developmental stages of the skeleton can result in hypoplasia of bones exposed to radiation therapy, demineralization associated with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, growth aberrations related to radiation therapy and altered vertebral height when radiation therapy is compounded by the effects of chemotherapy [36]. Similarly, chemotherapy can directly affect growing bones [36, 37]. Growing bone is most susceptible to the effects of radiation during the two periods of most rapid growth: less than 6 years of age and during puberty [38, 39]. The radiation injury is most likely related to injury of chondroblasts with inhibition of cartilaginous cells seen with single doses of 200 to 2000 cGy [5, 40]. Thus, the adverse impact of treatment, whether chemotherapy, radiation therapy or in combination, on the developing skeletal varies with patient age, type, distribution and intensity of therapy at the time of treatment [36, 39].

Scoliosis

Impaired vertebral growth can occur with doses of 1000 to 2000 cGy [41, 42]and can lead to short stature [38], altered vertebral body configuration [38, 42] and contribute to the development of scoliosis [40, 43, 44] and/or kyphosis [Figures 7 and 8] [44]. Probert and Parker reported changes in developing vertebral bodies when exposed to radiation doses of greater than 2000 rads [38]. Asymmetric exposure of the vertebral bodies may contribute to the development of scoliosis [40, 43, 44].

Figure 7. Chest wall deformity and scoliosis.

At the age of 6 years, this boy was diagnosed with Ewings sarcoma family of tumors right chest wall. He received multiagent chemotherapy, surgical resection and 504 cGy external beam irradiation. Over the course of 7 years, he developed significant scoliosis.

A. Axial chest computed tomography at the time of diagnosis shows the soft tissue mass arising from the right lateral chest wall.

B. Posteroanterior chest radiograph obtained 2 years after completion of therapy show chest wall deformity due to resection of several right thoracic ribs and pulmonary scarring. Note absence of a visible scoliosis.

C. Scoliosis series was obtained 7 years after therapy completion due to the presence of a ‘thoracic hump’ demonstrates a 52 degree mid-thoracic rotoscoliosis.

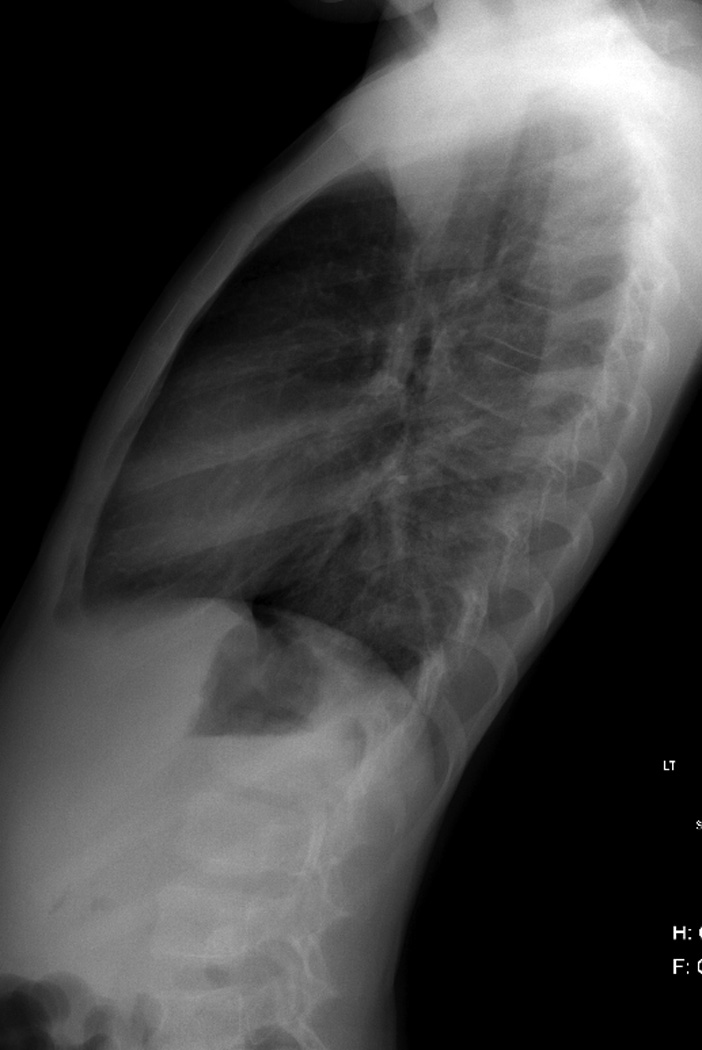

Figure 8. Rib dysplasia.

This 49-year-old woman was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at age 9 years was treated with mediastinal radiation therapy and multiagent chemotherapy.

A. and B. A., posteroanterior and lateral, B., chest radiographs demonstrate linear pulmonary scarring with mild cephalad retraction of the hila (arrows), a mild levoconvex mid-thoracic scoliosis (apex of the curve indicated by the arrowhead). The striking chest wall deformity with depression of the anterior chest wall resulted from radiation-induced rib dysplasia. Similarly, note the asymmetric size of the breasts (right smaller than left) and smaller volume of the right hemithorax compared to the left. The lateral view also readily demonstrates demineralization of the thoracic vertebral bodies.

C. Posteroanterior chest radiograph at the time of diagnosis show extensive mediastinal, paratracheal and right hilar adenopathy coupled with a large right pleural effusion.

Not only can therapeutic irradiation lead to growth disturbances and resultant scoliosis but may also result from chest wall resection. In children, the post-surgical scoliosis is progressive and related to the number of posterior ribs resected [45]

Clavicular growth

Merchant et al investigated the effect of asymmetric exposure of the clavicles to 1500 cGy as administered with hemi-mini-mantle irradiation for unilateral Hodgkin’s disease of the neck or supraclavicular region. The clavicle which was fully exposed to radiation therapy grew 0.5 cm less overall than those partially exposed (p=0.007), regardless of the patient’s age at the time of therapy (median age, 13.3 years; range, 5.1 to 18.9 years) [Figure 9]. Further, the effect on clavicular growth was more pronounced in the younger-aged patients (mean age, 9.9 years) than the older (mean age, 16.4 years; p=0.036) [46]. Thus, as with prior reports, the effect of radiation therapy on bone is influenced by patient age, therapeutic dose, and extent of tissues exposed [40].

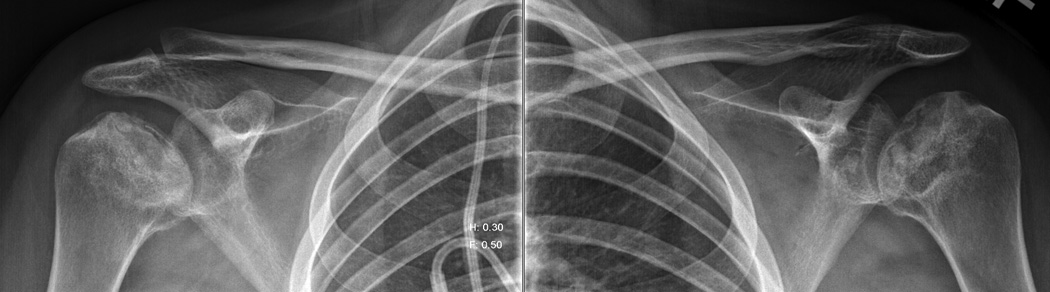

Figure 9. Asymmetric clavicular growth.

A 15-year-old boy was diagnosed with Stage IA Hodgkin’s disease of his right neck. In addition to multiagent chemotherapy, treatment included right hemi-mantle irradiation of 1500 cGy.

A. Axial computed tomography image of the neck at the time of diagnosis.

B. Chest x-ray obtained 15 years after completion of treatment demonstrates asymmetric clavicular growth. The right clavicle measures 2 cm shorter than the left.

Radiation-induced exostosis

Osteochondromas are the most common benign tumor of bone following radiation therapy [Figure 10] [47]. They manifest as a late effect of total body or local irradiation and have been reported as a long-term sequela of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [48, 49]. The median age of presentation and latency for osteochondromas following HSCT is 13.3 and 8.9 years, respectively [49, 50]. Amongst the risk factors investigated as contributing to their development following HSCT, only total body irradiation and young age at time of TBI and or HSCT have been consistently shown to significantly affect the risk of developing osteochondromas [49, 51].

Figure 10. Radiation-induced exostosis.

A 7-year-old girl returned 4 years after undergoing bone marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia because of a newly found “lump” in her right anterior chest. The preparative regimen for her bone marrow transplantation included total body irradiation.

A, posteroanterior chest radiograph was obtained which demonstrated expansion of the right anterior seventh rib (arrow).

B. Axial limited chest CT was performed through the rib for characterization of the abnormality shown on the chest radiograph and shows the typical appearance of an exostosis (skin marker).

The prevalence of osteochondramas is approximately 3% in the general population with the majority presenting as solitary osteochondromas unless in the setting of hereditary multiple exostosis [52]. Among survivors of HSCT, approximately 1% experience osteochondromas. Unlike the general population, only a slight majority of long-term survivors of HSCT experience solitary osteochondromas [49, 51]. In pediatric patients who undergo irradiation, damage to the epiphyseal plate causes a portion of the epiphyseal cartilage to migrate to the metaphyseal regions causing the formation of osteochondromas.

Osteochondromas that occur as a result of irradiation are radiographically indistinguishable from those that occur from other etiologies. Osteochondromas most commonly localize to the metaphysis of long bones particularly the femur and proximal tibia, with involvement of the flat bones being less common [49]. Clinically, osteochondromas present as painless slow growing masses that cause local distortion of tissue and depending on their proximity to neurovascular structures, osteochondromas can present with paresthesias or loss of peripheral pulse in the affected limb [52]. In addition to the above presentations, a minority of long-term survivors of HSCT are diagnosed with osteochondromas incidentally through the course of routine radiographic or clinical examination [49].

Radiographically, the appearance of osteochondromas can be described as cartilage capped protruding osseous lesions that have cortical and medullary contiguity with the overlying bone. The neck of an osteochondromas can either be wide or narrow giving it the appearance of being either sessile or pedunculated, respectively [47]. Osteochondromas can be easily recognized using radiographs. However, more complex lesions, such as those that involve the spine or shoulder can be better resolved with computed tomography [52]. Magnetic resonance imaging can be an accurate modality to distinguish osteochondromas from other osseous lesions due to the contrast of high and low intensity signal of the cartilaginous cap in T2 and T1 images, respectively [52].

Demineralization

Survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for deficits in bone mineral density which may lead to earlier onset and more severe osteoporosis and related fractures [53]. Attention to the integrity of bone mineral in the thoracic spine and documentation of compression fractures may be the first indication of such a deficit in survivors of childhood cancer. Though the best studied pediatric cancer population has been children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, such deficits are associated with a variety of pediatric malignancies and with bone marrow transplantation [54, 55].

Deficits in bone mineralization arise from a multitude of risk factors and include genetic predisposition [54], lifestyle factors such as suboptimal nutrition [53, 54], inadequate weight-bearing exercise [53, 54], treatment with osteotoxic chemotherapeutic agents particularly glucocorticoids but also associated with ifosfamide and methotrexate [37, 53, 54, 56], endocrinopathies [37, 53, 54], and radiation therapy whether localized to the thoracic spine or gonads [53] or cranial irradiation [37, 53].

Osteonecrosis

Children undergoing therapy for childhood cancer are at risk for osteonecrosis when treatment includes high dose glucocorticoids, bone marrow transplantation, and/or local radiation [Figure 11][57]. The reported prevalence of osteonecrosis in these survivors varies with the modality used to detect the toxicity (MR being the most sensitive modality), whether or not a report was based upon having or regardless of having symptoms, age at the time of diagnosis of the primary disease and type of treatment [58, 59]. In contrast to the general population, osteonecrosis in survivors of childhood cancer occurs as a multijoint toxicity in 60% of those in whom it develops. As reported by the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, the most frequent joints involved are the hips (72%), shoulders (24%) and knees (21%) [58].

Figure 11. Osteonecrosis.

This 20 year-old woman was diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at age 16-years and experienced multiple relapses of the disease. She was treated with multiagent chemotherapy that included high dose glucocorticoids. A posteroanterior chest radiograph showed changes of osteonecrosis of the left humeral headA. Dedicated radiographs of the shoulders confirmed the advanced osteonecrotic changes of both humeral heads with crescent signs (arrows), collapse of the articular surfaces, and intermixed areas of sclerosis and cystic changes.

Summary

The rapidly growing population of survivors of childhood cancer underscores the need for recognizing potential sequelae of disease and therapy and knowledge of risk factors for their development. While numerous reports are available regarding second malignant neoplasms in this population, only in the more recent past have investigations and understanding of adverse toxicities manifesting after completion of therapy been undertaken. It is with the hope of enhancing care of survivors of childhood cancer, that this review based upon the commonly obtained chest radiograph has been developed. Though not meant to be all-inclusive, this work serves as a starting point to enhance the acumen of imaging healthcare providers and thus, improve the care of these patients.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms. Sandra Gaither for manuscript preparation.

Supported in part by grant P30 CA-21765 from the National Institutes of Health, a Center of Excellence grant from the State of Tennessee, the Le Bonheur Foundation (Memphis TN), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Reference List

- 1.Armenian SH, Landier W, Hudson MM, et al. Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: survivorship and outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1063–1068. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, et al. Long-term survivors of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1033–1040. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman DL, Constine LS, Halperin EC, et al. Pediatric Radiation Oncology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. Late Effects of Cancer Treatment; pp. 353–396. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juweid ME. FDG-PET/CT in lymphoma. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;727:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-062-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radford JA, Cowan RA, Flanagan M, et al. The significance of residual mediastinal abnormality on the chest radiograph following treatment for Hodgkin's disease. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:940–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.6.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luker GD, Siegel MJ. Mediastinal Hodgkin disease in children: response to therapy. Radiology. 1993;189:737–740. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.3.8234698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brisse H, Pacquement H, Burdairon E, et al. Outcome of residual mediastinal masses of thoracic lymphomas in children: impact on management and radiological follow-up strategy. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s002470050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di CE, Cerone G, Enrici RM, et al. MRI characterization of residual mediastinal masses in Hodgkin's disease: long-term follow-up. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmouni A, Divine M, Lepage E, et al. Mediastinal lymphoma: quantitative changes in gadolinium enhancement at MR imaging after treatment. Radiology. 2001;219:621–628. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.3.r01jn06621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasr A, Stulberg J, Weitzman S, Gerstle JT. Assessment of residual posttreatment masses in Hodgkin's disease and the need for biopsy in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:972–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connors JM. Positron emission tomography in the management of Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:317–322. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Liu Y, et al. Pulmonary complications in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2002;95:2431–2441. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson MM, Mulrooney DA, Bowers DC, et al. High-risk populations identified in Childhood Cancer Survivor Study investigations: implications for risk-based surveillance. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2405–2414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin P, Cassarett GW. Clinical Radiation Pathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liles A, Blatt J, Morris D, et al. Monitoring pulmonary complications in long-term childhood cancer survivors: guidelines for the primary care physician. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:531–539. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motosue MS, Zhu L, Srivastava K, et al. Pulmonary function after whole lung irradiation in pediatric patients with solid malignancies. Cancer. 2012;118:1450–1456. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang TT, Hudson MM, Stokes DC, et al. Pulmonary outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review. Chest. 2011;140:881–901. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nenadov BM, Meresse V, Hartmann O, Gaultier C. Long-term pulmonary sequelae after autologous bone marrow transplantation in children without total body irradiation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16:771–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Travis LB, Ng AK, Allan JM, et al. Second malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease following radiotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:357–370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurt BA, Armstrong GT, Cash DK, et al. Primary care management of the childhood cancer survivor. J Pediatr. 2008;152:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer LC, van Dalen EC, Offringa M, Voute PA. Frequency and risk factors of anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:503–512. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orgel E, Zung L, Ji L, et al. Early cardiac outcomes following contemporary treatment for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a North American perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1528–1533. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krischer JP, Epstein S, Cuthbertson DD, et al. Clinical cardiotoxicity following anthracycline treatment for childhood cancer: the Pediatric Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1544–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, van DE, et al. High risk of symptomatic cardiac events in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1429–1437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipshultz SE. Exposure to anthracyclines during childhood causes cardiac injury. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:S8–S14. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ylanen K, Poutanen T, Savikurki-Heikkila P, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of the late effects of anthracyclines among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1539–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun-Falco O, Schultze U, Meinhof W, Goldschmidt H. Contact radiotherapy of cutaneous hemangiomas: therapeutic effects and radiation sequelae in 818 patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 1975;253:237–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00561150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolar J, Bek V, Vrabec R. Hypoplasia of the growing breast after contact-x-ray therapy for cutaneous angiomas. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macklis RM, Oltikar A, Sallan SE. Wilms' tumor patients with pulmonary metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinter AB, Hock A, Kajtar P, Dober I. Long-term follow-up of cancer in neonates and infants: a national survey of 142 patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:233–239. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weidman AI, Zimany A, Kopf AW. Underdevelopment of the human breast after radiotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:708–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furst CJ, Lundell M, Ahlback SO, Holm LE. Breast hypoplasia following irradiation of the female breast in infancy and early childhood. Acta Oncol. 1989;28:519–523. doi: 10.3109/02841868909092262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenney LB, Yasui Y, Inskip PD, et al. Breast cancer after childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:590–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papadakis V, Tan C, Heller G, Sklar C. Growth and final height after treatment for childhood Hodgkin disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18:272–276. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Leeuwen BL, Kamps WA, Jansen HW, Hoekstra HJ. The effect of chemotherapy on the growing skeleton. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:363–376. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Probert JC, Parker BR. The effects of radiation therapy on bone growth. Radiology. 1975;114:155–162. doi: 10.1148/114.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dorr W, Kallfels S, Herrmann T. Late bone and soft tissue sequelae of childhood radiotherapy. Relevance of treatment age and radiation dose in 146 children treated between 1970 and 1997. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:529–534. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawson WB. Growth impairment following radiotherapy in childhood. Clin Radiol. 1968;19:241–256. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(68)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell MJ, Logan PM. Radiation-induced changes in bone. Radiographics. 1998;18:1125–1136. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.5.9747611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuhauser EB, Wittenborg MH, Berman CZ, Cohen J. Irradiation effects of roentgen therapy on the growing spine. Radiology. 1952;59:637–650. doi: 10.1148/59.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker RG, Berry HC. Late effects of therapeutic irradiation on the skeleton and bone marrow. Cancer. 1976;37:1162–1171. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197602)37:2+<1162::aid-cncr2820370827>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makipernaa A, Heikkila JT, Merikanto J, et al. Spinal deformity induced by radiotherapy for solid tumours in childhood: a long-term follow up study. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:197–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01956143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeRosa GP. Progressive scoliosis following chest wall resection in children. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10:618–622. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merchant TE, Nguyen L, Nguyen D, et al. Differential attenuation of clavicle growth after asymmetric mantle radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, et al. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:1407–1434. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.5.g00se171407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harper GD, cks-Mireaux C, Leiper AD. Total body irradiation-induced osteochondromata. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:356–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faraci M, Bagnasco F, Corti P, et al. Osteochondroma after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood. An Italian study on behalf of the AIEOP-HSCT group. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bordigoni P, Turello R, Clement L, et al. Osteochondroma after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: report of eight cases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:611–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Danner-Koptik K, Kletzel M, Dilley KJ. Exostoses as a long-term sequela after pediatric hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation: potential causes and increase risk of secondary malignancies from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1267–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, et al. Osteochondromas: review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo. 2008;22:633–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang MJ, Lim JS. Bone mineral density deficits in childhood cancer survivors: Pathophysiology, prevalence, screening, and management. Korean J Pediatr. 2013;56:60–67. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2013.56.2.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, et al. Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e705–e713. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaste SC, Shidler TJ, Tong X, et al. Bone mineral density and osteonecrosis in survivors of childhood allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:435–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson CL, Ness KK. Bone Mineral Density Deficits and Fractures in Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kadan-Lottick NS, Dinu I, Wasilewski-Masker K, et al. Osteonecrosis in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3038–3045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, et al. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2339–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaste SC, Karimova EJ, Neel MD. Osteonecrosis in children after therapy for malignancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:1011–1018. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]