Abstract

Somatic cells are reprogrammed to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by overexpression of a combination of defined transcription factors. We generated iPSCs from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (with Oct4-GFP reporter) by transfection of pCX-OSK-2A (Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4) and pCX-cMyc vectors. We could generate partially reprogrammed cells (XiPS-7), which maintained more than 20 passages in a partially reprogrammed state; the cells expressed Nanog but were Oct4-GFP negative. When the cells were transferred to serum-free medium (with serum replacement and basic fibroblast growth factor), the XiPS-7 cells converted to Oct4-GFP-positive iPSCs (XiPS-7c, fully reprogrammed cells) with ESC-like properties. During the conversion of XiPS-7 to XiPS-7c, we found several clusters of slowly reprogrammed genes, which were activated at later stages of reprogramming. Our results suggest that partial reprogrammed cells can be induced to full reprogramming status by serum-free medium, in which stem cell maintenance- and gamete generation-related genes were upregulated. These long-term expandable partially reprogrammed cells can be used to verify the mechanism of reprogramming.

Introduction

Yamanaka and colleagues were the first to report that mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) could be reprogrammed to pluripotent stem cells by retroviral transduction of four transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) [1]. These induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) closely resemble mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) in morphology, gene expression, differentiation potential into all three germ layers, and germline contribution [1,2]. With the ability to differentiate into all body cell types, iPSCs provide a valuable tool for studying mechanisms of development and tissue specification and for disease model systems [3–6]. However, the basic mechanisms underlying pluripotential reprogramming by defined factors remain poorly understood. After the first success of such reprogramming [1,7], many groups have attempted to decipher the reprogramming process at the cellular and molecular level by examining morphological, transcriptional, and epigenetic changes [8–14]. The reprogramming process in iPSC generation proceeds through two main waves of molecular remodeling events [15]. In the first wave, differentiated cells undergo key changes associated with the initiation phase of reprogramming such as mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and erasure of tissue-specific markers [11]. The second wave is associated with the maturation and stabilization phases of reprogramming, such as activation of pluripotency markers (Oct4, Nanog, and Sall4 in maturation phase; Utf1, Lin28a, Dppa2, and Dppa4 in stabilization phase) and maintenance of a stable pluripotent state by epigenetic modification [10,13,14]. Moreover, intermediate-stage (or partially reprogrammed cells) stably accumulates as a major population during reprogramming, whereas fully reprogrammed cells rarely accumulate [12,16–18]. Prepluripotent iPSCs (pre-iPSCs) are an intermediate cell type that have an mESC-like morphology but do not express pluripotency genes such as Dppa5, Zfp42 (also known as Rex1), and Nanog. Pre-iPSCs derived from women possess an inactive X chromosome [17,18]. Many cells in the reprogramming process may be locked in the intermediate stage and disappear, while only a few cells are reprogrammed into the fully pluripotent state. Exploring mechanisms that convert partially reprogrammed cells into fully reprogrammed iPSCs would provide a tremendous boost to reprogramming and stem cell research. However, intermediate-stage (or partially reprogrammed) cells are transient during reprogramming and difficult to isolate and maintain as intermediates in culture.

Some pluripotency markers are essential for complete reprogramming and maintenance of the ground state of pluripotency. Expression of endogenous Nanog is a crucial event during reprogramming into the pluripotent ground state [19]. Nanog has the capacity to overcome multiple barriers to reprogramming in mouse cells [20]. NANOG also enhances molecular reprogramming in human somatic cells [21]. In this study, we found that Nanog is expressed in partially reprogrammed cells, which self-renewed for more than 20 passages in vitro. These cells were converted into fully reprogrammed iPSCs with mESC-like properties in serum-free medium [with serum replacement (SR) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)]. In addition, global gene expression profiles and gene ontology (GO) revealed that the genes associated with partial reprogramming were related to stem cell maintenance, survival, and germ cell development.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

We used MEFs as somatic cells for reprogramming. MEFs were derived from OG2/Rosa26 heterozygous double transgenic 13.5-day postcoitum (dpc) mouse embryos, which were generated by crossing the Rosa26 (carrying neo/lacZ transgene) strain with the OG2 transgenic strain (carrying GFP under the control of the Oct4 promoter, Oct4-GFP) over several generations [22,23]. Animal handling was in accordance with the animal protection guidelines of Konkuk University and Korean animal protection laws. MEFs were maintained in fibroblast medium: high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) and 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Mouse ESCs and iPSCs were grown on MEF feeder cells that had been inactivated with 0.01 mg/mL mitomycin C in standard mouse ESC culture medium: DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin, nonessential amino acids (NEAA; Gibco BRL), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1,000 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (ESGRO; Chemicon). XiPS-7 cells were reprogrammed on inactivated MEFs in KOSR-based medium: DMEM/F12 (Gibco BRL) containing 20% knockout SR (Gibco BRL), 2 mM glutamine, NEAA, and 5 ng/mL bFGF.

Generation of iPSCs

pCX-OKS-2A [Oct4 (O), Klf4 (K), and Sox2 (S), each separated by a different 2A sequence] and pCX-cMyc, were purchased from Addgene. The plasmids were mixed with 3 μg pCX-OKS-2A and 1 μg pCX-cMyc. MEFs were seeded at 1×105 cells/well in six-well plates (day 0). Plasmids were introduced with 1.2 μL of Xfect™ transfection reagent (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Fig. 1A). From day 4, the transfected MEFs were cultured in mouse ESC culture medium containing LIF. On day 9, the cells were harvested with trypsin and plated on 100-mm dishes with MEF feeder cells. On days 25–28, Oct4-GFP-positive or -negative colonies were picked for expansion and maintained in mouse ESC culture medium.

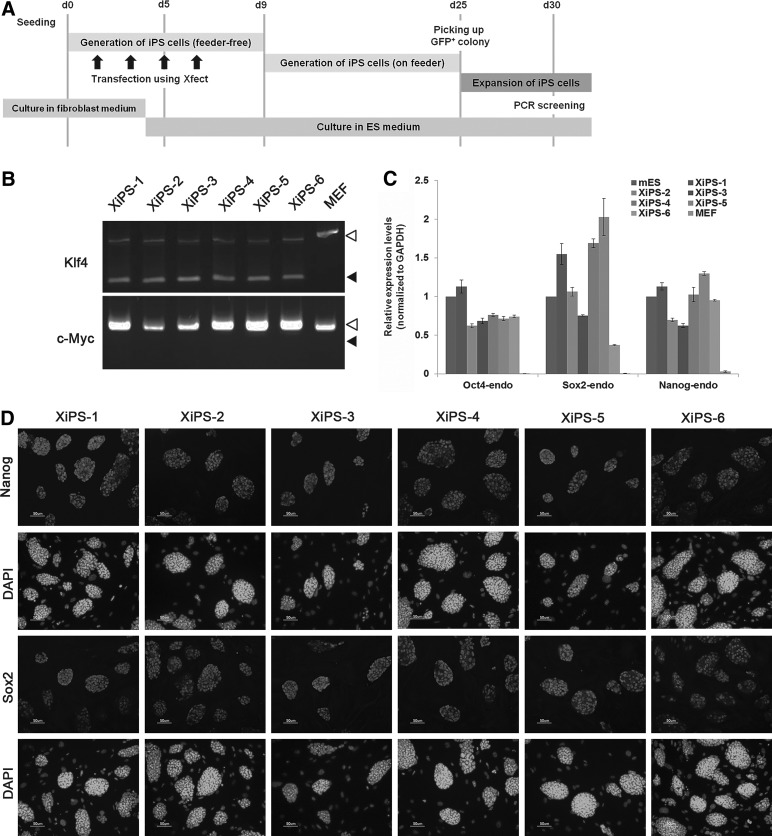

FIG. 1.

Generation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells using pCX-OSK (Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4) and pCX-cMyc. (A) Schematic representation of iPS cell generation using pCX-OSK and pCX-cMyc. (B) Detection of genomic integration of exogenous Klf4 and c-Myc by PCR. White and black arrowheads indicate endogenous alleles and exogenous transgenes, respectively. MEFs were used as a negative control. (C) Analysis of the endogenous expression levels of the pluripotent markers (Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog) by qRT-PCR. Relative expression of pluripotent markers was calculated relative to GAPDH. Data represent mean±SEM. (D) Expression of Nanog and Sox2 in XiPS cell lines (1–6) by immunocytochemistry. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar=50 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR.

Integration analysis

Transgene integration was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR): 50 ng genomic DNA was amplified with Taq polymerase and screened with primer sets for pCX-OKS-2A (primers for Klf4) and pCX-cMyc [24]. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd).

Bisulfite DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite to convert all unmethylated cytosine residues into uracil residues using EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, purified genomic DNA (0.5–1 μg) was denatured at 99°C and then incubated at 60°C. Modified DNA (ie, after desulfonation, neutralization, and desalting) was diluted with 20 μL distilled water. Bisulfite PCR amplification was performed with 1–2 μL aliquots of modified DNA for each reaction. PCR amplification of the Oct4 and Nanog promoter regions was performed as described [25]. The PCR products were subcloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The reconstructed plasmids were purified, and individual clones were sequenced (Solgent Corporation). Clones with ≥90% cytosine conversion were accepted, and all possible clonalities were excluded based on criteria in BiQ Analyzer software (Max Planck Society). Primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Alkaline phosphatase staining

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining was performed with the AP detection kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS, and treated with AP solution containing Fast Red Violet and Naphthol AS-BI phosphate (Millipore) for 15 min at room temperature.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. Cells were treated with PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 0.03% Triton X-100 for 45 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies were anti-Nanog (1:250 dilution; Chemicon), anti-Sox2 (1:1,000 dilution; Chemicon), anti-SSEA-1 (1:250 dilution; R&D), anti-β III tubulin (Tuj1; 1:1,000 dilution, Chemicon), anti-Brachyury (1:1,000 dilution; Chemicon), and anti-Sox17 (1:200 dilution; R&D). Fluorescence-labeled (Alexa Fluor 568; Molecular Probes) secondary antibody was used according to the manufacturer's specifications.

In vitro differentiation

iPSCs were transferred into a suspension culture dish after trypsinization and cultured for 3 days in DMEM (10% FBS) without LIF. The embryoid bodies (EBs) were plated on 0.1% gelatin-coated glass chamber slides and cultured in differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS in the absence of LIF) for 12 days. Differentiated cells were stained for germ layer markers: Tuj1 for ectoderm, Brachyury for mesoderm, and Sox17 for endoderm.

Teratoma formation

The properties associated with teratoma formation were evaluated in trypsin-dissociated iPSCs. We subcutaneously transplanted 1×106 cells suspended in DMEM into the testis of 5-week-old nude mice. After 5 weeks, the tumors were dissected and fixed in 4% PFA, processed through graded ethanol, and embedded in paraffin after sectioning with hematoxylin/eosin.

Chimera formation analysis

XiPS cells were aggregated with denuded postcompacted eight-cell-stage embryos to obtain an aggregate chimera. Eight-cell embryos flushed from 2.5-dpc B6D2F1 female mice were cultured in microdrops of embryo culture medium under mineral oil. After cells were trypsinized for 10 s, clumps of iPSCs (4–10 cells) were selected and transferred into microdrops containing zona-free eight-cell embryos. Morular-stage embryos aggregated with XiPS cells were cultured overnight at 37°C, 55% CO2. The aggregated blastocysts were transferred into one uterine horn of 2.5-dpc pseudopregnant recipients. Animals were maintained and used for experimentation under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Max-Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine and Konkuk University. The institutional review board specifically approved this study (IACUC090003).

X-gal staining

For whole fetal embryo staining, collected fetuses were rinsed with PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C. Fetuses were rinsed thrice at room temperature in PBS containing 5 mM EGTA, 0.01% deoxycholate, 0.02% NP40, and 2 mM MgCl2. The specimens were washed with PBS and stained in X-gal staining solution: PBS supplemented with 1 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-galactosidase (X-gal; Promega), 5 mM K2Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, and 1 mM MgCl2. Blue staining was visualized by light microscopy.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with the MiniRNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed with SuperScriptIII Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and Oligo (dt)20-primer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green quantitative PCR mix (Takara) and a LightCycler5480 instrument (Roche). Duplicate amplifications were performed for each target gene with three wells serving as negative controls. Quantities were estimated by the comparative Ct method normalized to GAPDH and presented as a percentage of biological controls. Primer sequences are described in Supplementary Table S1.

Microarray-based analysis

Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and digested with DNase I (RNase-free DNase; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was amplified, biotinylated, and purified using the Ambion Illumina RNA amplification kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled cRNA samples (750 ng) were hybridized to each MouseRef-8 v2 Expression BeadChip. Signal detection was performed with Amersham Fluorolink Streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare Bio-Science) according to the bead array manual. Arrays were scanned with an Illumina Bead Array Reader according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Raw data were extracted using the software provided by the manufacturer (Illumina GenomeStudio v2011.1, Gene Expression Module v1.9.0). Array data were filtered by a detection P value <0.05 in at least 50% samples. Selected probe signal was log transformed and normalized by the quantile method. Comparative analysis was performed using LPE test and fold change. False discovery rate was controlled by adjusting the P value with the Benjamini–Hochberg algorithm. Hierarchical clustering was performed using complete linkage and Pearson distance as a measure of similarity.

Results

Generation of fully reprogrammed iPSCs by transfection of plasmid DNAs

To generate iPSCs without viral vectors, we transfected pCX-OKS-2A (Oct4, Klf4, and Sox2) and pCX-cMyc [26] into MEFs using a biodegradable nanoparticle, Xfect. Since MEFs were derived from the Oct4-GFP/Rosa26 double transgenic mouse, GFP was activated on pluripotential reprogramming. The timeline of the reprogramming protocol is depicted in Fig. 1A. Serial transfection (four times) of the vectors into MEFs successfully generated GFP-positive colonies at 25 days after nanoparticle-mediated transfection (Supplementary Fig. S1A). We derived six iPS cell lines, referred to as “XiPS cells,” from Xfect-mediated transfection (lines 1–6). All six XiPS cell lines expressed Oct4-GFP and were positive for AP activity (Supplementary Fig. S1B). To test for transgene integration into the host genome, we genotyped the XiPS cell lines using two primer pairs (Klf4 and c-Myc) specifically designed to amplify regions of the pCX-OKS and pCX-cMyc vectors [24]. All six XiPS cell lines were free of pCX-cMyc but had integrated pCX-OKS (Fig. 1B). Endogenous pluripotency markers Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog were expressed in all XiPS cell lines, comparable to control mESCs (Fig. 1C). Immunocytochemistry also confirmed the expression of Nanog and Sox2 (Fig. 1D).

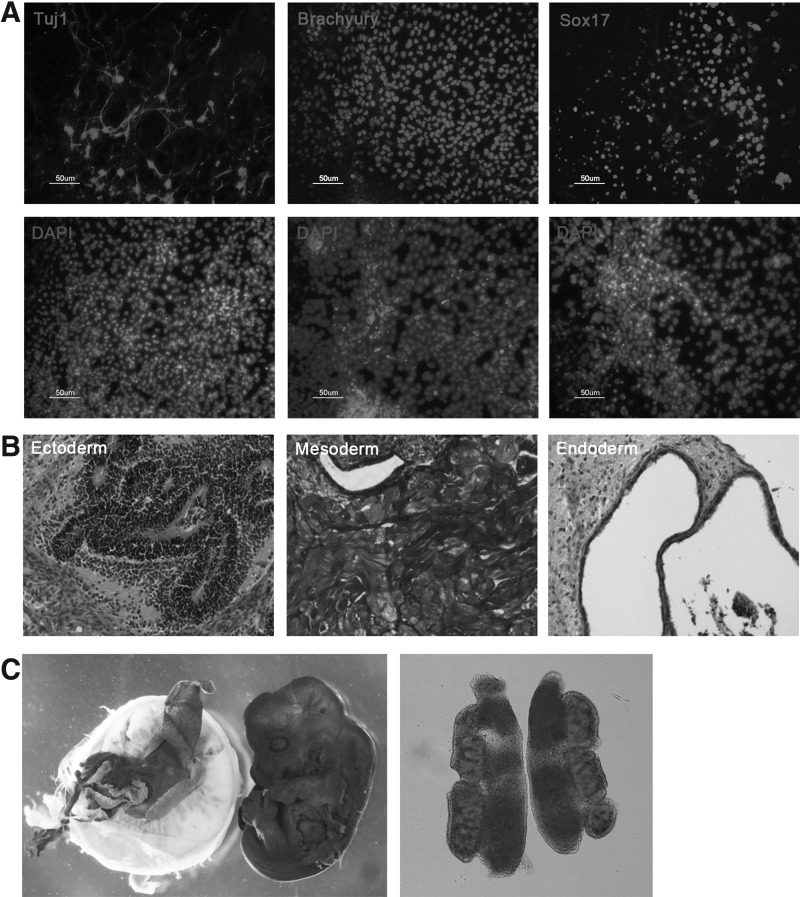

Oct4-GFP-positive iPSCs (XiPS-1 line) were differentiated in vitro into ectoderm (Tuj1), mesoderm (Brachyury), and endoderm (Sox17) (Fig. 2A). XiPS-1 cells also formed teratomas containing cells of all three germ layers after transplantation into the testis capsule of immunocompromised mice (Fig. 2B). To confirm the developmental potential of XiPS-1 cells, we performed chimera formation analysis by aggregation with zona-free morula embryos. After transfer into the uterus of pseudopregnant mice, the XiPS-1 cells formed chimeric embryos (13.5 dpc) showing germline contribution (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrate that transfection of plasmid DNA using nanoparticles can reprogram MEFs to pluripotent cells with properties similar to those of mouse ESCs.

FIG. 2.

In vitro and in vivo differentiation potential of XiPS-1 cells. (A) In vitro differentiation potential of XiPS-1 cells by EB formation. Expression of Tuj1 (ectoderm), Brachyury (mesoderm), and Sox17 (endoderm) in differentiated XiPS-1 cells by immunocytochemistry. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar=50 μm. (B) In vivo differentiation potential of XiPS-1 cells by teratoma formation. The tissues of all three germ layers, including ectoderm (neural rosette), mesoderm (muscle fibers), and endoderm (gut-like epithelium), were detected in XiPS-1 cell-derived teratoma sections. Original magnification 100×. (C) A chimeric embryo of XiPS-1 cells was stained with X-gal. XiPS-1 cells contribute to germline cell development (Oct4-GFP positive) in a 13.5 dpc male gonad. dpc, day postcoitum; EB, embryoid body.

Generation of long-term expandable partially reprogrammed cells by plasmid transfection

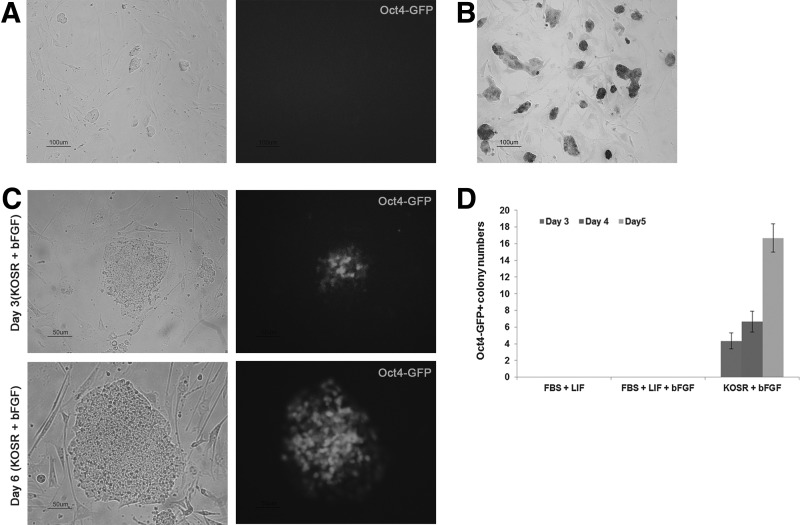

Although many Oct4-GFP-positive colonies were generated by plasmid-nanoparticle transfection, we also observed mESC-like cells forming relatively flat colonies without Oct4-GFP expression in the same culture dish (Fig. 3A). When the GFP-negative ESC-like cells were picked and cultured under mESC conditions, ESC-like colonies without Oct4-GFP activation were maintained; these were called the XiPS-7 cell line. Although the established XiPS-7 cells did not express Oct4-GFP for approximately 20 passages, they were positive for AP (Fig. 3B). Since they were Oct4-GFP negative, XiPS-7 did not express endogenous Oct4 (Fig. 4B); however, XiPS-7 expressed high levels of Nanog (Fig. 4B, C). Therefore, we regarded XiPS-7 as partially reprogrammed cells that were long-term expandable.

FIG. 3.

Successful conversion from Oct4-GFP-negative cells to Oct4-GFP-positive cells. (A) Oct4-GFP-negative colonies detected during somatic cell reprogramming. Scale bar=100 μm. (B) AP staining of the Oct4-GFP-negative cells (XiPS-7). Scale bar=100 μm. (C) XiPS-7 cells were converted to Oct4-GFP-positive cells (XiPS-7c) in KOSR-based media with bFGF. Oct4-GFP-positive cells (day 3 and 6) are shown in phase-contrast and fluorescence images. Scale bar=50 μm. (D) The number of Oct4-GFP-positive colonies was counted on days 3, 4, and 5 after changing conditions. Error bars are ±SD of the mean. AP, alkaline phosphatase; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor.

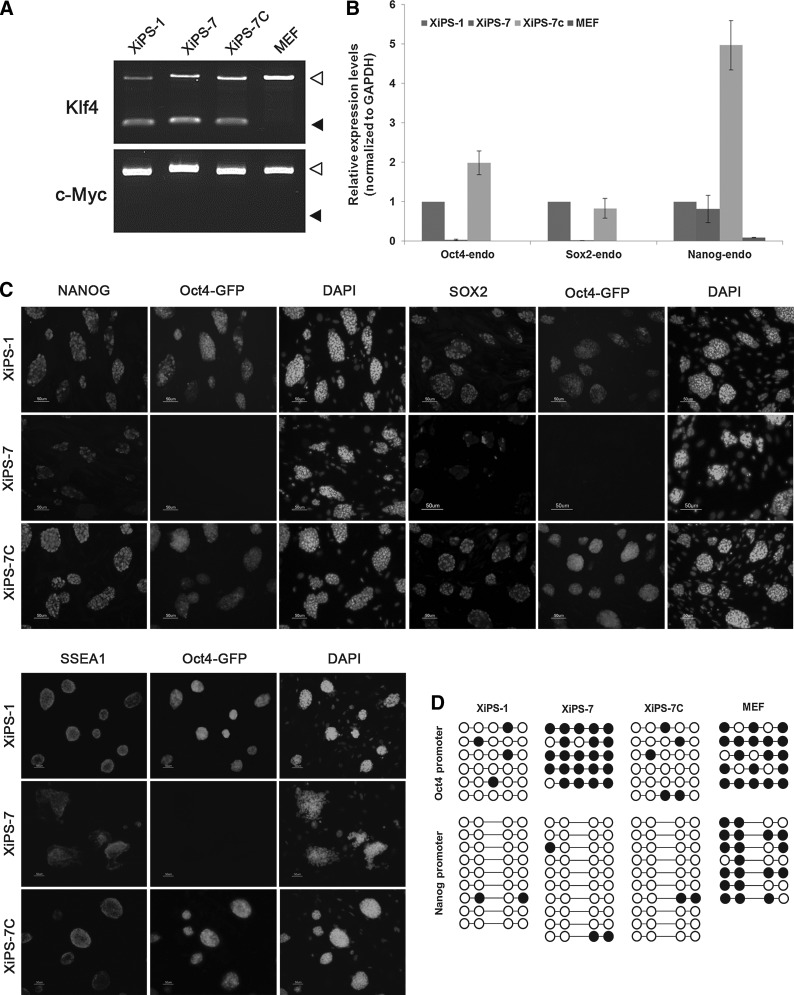

FIG. 4.

Characterization of XiPS-7 and XiPS-7c cells. (A) RT-PCR analysis for genomic integration of exogenous Klf4 and c-Myc. White and black arrowheads indicate endogenous alleles and exogenous transgenes, respectively. MEFs were used as a negative control. (B) qRT-PCR analysis for endogenous expression of the pluripotent markers Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog. Relative expression was calculated by normalizing to GAPDH. Data represent mean±SEM. (C) Expression of Nanog, Sox2, SSEA-1, and Oct4-GFP in XiPS-1, XiPS-7, and XiPS-7c cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar=50 μm. (D) Bisulfite genomic sequencing of the promoter regions of Oct4 and Nanog in XiPS-1, XiPS-7, XiPS-7c cells, and MEFs. RT-PCR, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Partially reprogrammed cells (XiPS-7) progress through reprogramming in serum-free defined medium

Typically, mouse iPSCs are generated from somatic cells in conventional ESC culture conditions with FBS and LIF with feeders' support [1,2,27,28]. LIF and BMP signaling pathways are essential for maintaining the pluripotency of mESCs, whereas the bFGF supplementation leads to differentiation [29–31]. ESCs cultured in FBS and LIF receive differentiation signals from FBS, which were blocked by LIF [32,33]. Therefore, serum-free culture may be suitable for ground-state pluripotency. Thus, iPSC colonies can be obtained at day 8 postinfection when reprogramming occurs in defined SR-based medium with LIF [23,34]. Moreover, iPSCs could also be generated and maintained in mESC medium supplemented with bFGF [35]. Therefore, we examined XiPS-7 cell culture in serum-free medium supplemented with bFGF. To our surprise, at day 3 after culture in SR-based medium, colonies of XiPS-7 cells were converted to dome-like colonies and became Oct4-GFP positive (Fig. 3C). These converted Oct4-GFP-positive (XiPS-7c) cells were picked and expanded. To verify that complete reprogramming of XiPS-7 to XiPS-7c is caused by serum-free bFGF culture conditions, XiPS-7 cells were cultured in three different media: mESC medium with LIF or with both LIF and bFGF, and SR-based medium with bFGF. Oct4-GFP-positive cells were observed in SR-based media but not in mESC medium with LIF or LIF/bFGF (Fig. 3D). Next, we checked whether these results were reproducible in another partially reprogrammed iPS cell line, XiPS-13 cells, which were Oct4-GFP negative but expressed Nanog. XiPS-13 cells also could be converted to dome-like colonies and became Oct4-GFP positive at day 2–4 after culture in SR-based medium (Supplementary Fig. S2A). These results suggest that partially reprogrammed cells progress through reprogramming in serum-free (SR-based) medium.

Partially reprogrammed cells (XiPS-7) express Nanog but not Oct4 and Sox2

We tested for genomic integration of pCX-OKS and pCX-cMyc in XiPS-7 and XiPS-7c cells and found that the XiPS-7 cells were free of pCX-cMyc but had pCX-OKS integration (Fig. 4A). Nevertheless, we speculated that XiPS-7c cells could be in a completely reprogrammed state and were pluripotent unlike XiPS-7 cells, which are in an intermediate state. To determine whether XiPS-7c cells were completely reprogrammed pluripotent, we analyzed transcript levels of endogenous core pluripotency markers Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S3). Interestingly, Nanog was expressed in XiPS-7 cells in which endogenous Oct4 and Sox2 were not expressed (Fig. 4B). Nanog protein was also detected in XiPS-7 cells but not expressed in MEFs (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). A recent report demonstrated that the inner cell mass of Oct4-deficient blastocysts in which both maternal and zygotic Oct4 were silent still expressed Nanog [36], suggesting that Oct4 and Nanog do not need to be co-expressed in certain cells. However, XiPS-7c cells expressed all three core transcription factors, Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog. Gene expression was confirmed by immunocytochemistry. Oct4-GFP-positive XiPS-7c cells stained positive for Nanog, Sox2, and SSEA-1; whereas XiPS-7 cells were positive for Nanog and SSEA-1 but weakly positive for Sox2 (Fig. 4C). Next, the DNA methylation status of the Oct4 and Nanog promoter regions was determined by bisulfite genomic sequencing. The Oct4 promoter regions, which were hypermethylated in XiPS-7, were demethylated after conversion to XiPS-7c (Fig. 4D); however, the Nanog promoter region of all three Nanog-expressing cell types (XiPS-1, XiPS-7c, and XiPS-7) was completely unmethylated (Fig. 4D).

Gene expression profile of XiPS-7 and XiPS-7c cells

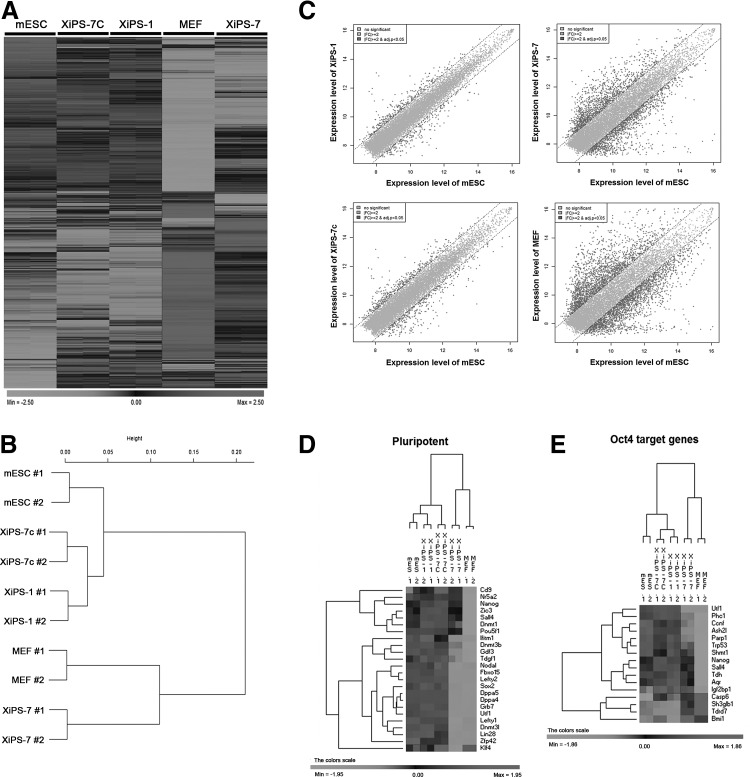

To compare the molecular signatures of XiPS-7, XiPS-7c, and XiPS-1 cells, we performed gene expression profiles using microarrays (Illumina's MouseRef-8 v2 Expression BeadChip). Counting only those with a fold change (FC) greater than 2, there were 5,807 regulated transcripts (with regard to mESCs). Pearson correlation analysis was used to cluster the cells. The heat map and hierarchical clustering analyses showed that the global gene expression patterns of XiPS-1 and XiPS-7c were similar to mESCs, whereas XiPS-7 clustered closer to MEFs than to mESCs, XiPS-1, and XiPS-7c (Fig. 5A, B). Scatter plot analysis also showed that XiPS-7 was more differentiated from mESCs than from XiPS-7c and XiPS-1 (Fig. 5C). Expression of pluripotency-related genes in XiPS-7 clustered differently from mESC, XiPS-1, and XiPS-7c (except Cd9, Nr5a2, and Nanog) (Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. S2B). Since XiPS-7 do not express endogenous Oct4, we checked the expression of Oct4 target genes. As expected, XiPS-7 expressed very low levels of Oct4 target genes (except Nanog) in comparison to completely reprogrammed cells that express Oct4-GFP (XiPS-1 and XiPS-7c) (Fig. 5E). In contrast, Oct4 target genes that are not expressed in ESCs, such as Casp6, Sh3glb1, Tdrd7, and Bmi1, were highly expressed in XiPS-7 and MEF (Fig. 5E).

FIG. 5.

Contrasting global transcriptomes of five cell samples. (A) Heat map of global gene expression in mouse embryonic stem, XiPS-1, XiPS-7, XiP-7c cells, and MEFs. (B) Hierarchical clustering analysis of the global gene expression profiles using the average linkage and the Pearson distance. The expression profiles of XiPs-7c, XiPS-1, and mESCs are clustered in a similar manner as XiPS-7 and MEFs. (C) Represent, respectively, log–log scatter plot between mESC and XiPS-1, mESC and XiPS-7, mESC-XiPS-7c, and mESC and MEFs. (D) Heat map of pluripotent genes in five cell samples. (E) Heap map of Oct4 target genes in five cell samples. mESCs, mouse embryonic stem cells.

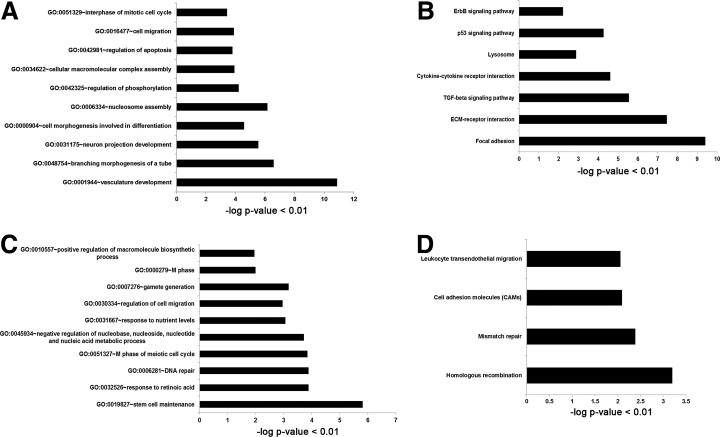

GO analysis was conducted to categorize the functions of the differentially expressed genes in partially (XiPS-7) and fully reprogrammed cells (XiPS-7c). We isolated differentially expressed genes [>±3-FC] in XiPS-7 versus XiPS-7c cells. We found that 625 probes were upregulated and 421 probes were downregulated in XiPS-7 versus XiPS-7c cells. We performed the GO term and KEGG pathway annotation using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) and found that the top 10 most enriched categories of upregulated genes, which had ≥1.3 enrichment scores with the classification stringency set to high, included “vasculature development,” “branching morphogenesis of a tube,” “nucleosome assembly,” “cell migration,” “neuron projection development,” “interphase of mitotic cell cycle,” “regulation of phosphorylation,” “cell morphogenesis involved in differentiation,” “cellular macromolecular complex assembly,” and “regulation of apoptosis” (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, upregulated genes in partially reprogrammed cells were mainly associated with tissue development. On the other hand, the top 10 most enriched categories of downregulated genes in XiPS-7 (ie, upregulated genes in XiPS-7c), which may be associated with the fully reprogrammed state, were “stem cell maintenance,” “gamete generation,” “response to retinoic acid,” “DNA repair,” “M phase of meiotic cell cycle,” “M phase,” “negative regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic process,” “positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process,” “response to nutrient levels,” and “regulation of cell migration” (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Table S4). In addition, the pathway annotation of up- and downregulated genes was performed based on scoring and visualization of the pathways collected in the KEGG database (www.genome.jp/kegg). The upregulated genes included “focal adhesion,” “transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta signaling pathway,” “extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction,” “p53 signaling pathway,” “ErbB signaling pathway,” and “cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction” (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Table S3) and the downregulated genes included “homologous recombination,” “mismatch repair,” “cell adhesion molecules,” and “leukocyte transendothelial migration” (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Table S5). We also looked for enrichment in the GO and KEGG pathways of regulated transcripts (<± 3-FC) between XiPS-7c cells and mESCs. The GO analysis of 106 upregulated genes based on biological process terms revealed that “tissue development,” “regulation of multicellular organismal process,” “collagen fibril organization,” “tube development,” “development process,” “negative regulation of coagulation,” and “response to organic substance” had ≥1.3 enrichment scores (Supplementary Fig. S6A and Supplementary Table S6). According to KEGG pathway enrichment, we obtained “ECM-receptor interaction” and “focal adhesion” pathways in the upregulated genes (Supplementary Fig. S6B and Supplementary Table S7). However, we found no categories of GO and KEGG pathway in the 60 downregulated genes. Therefore, microarray data suggest that the gene expression pattern of partially reprogrammed cells (XiPS-7 cells) is distinct from other pluripotent cells, including mESCs, XiPS-1, and XiPS-7c, mainly in tissue development, stem cell maintenance, and germ cell development. After complete reprogramming from XiPS-7 to XiPS-7c, the XiPS-7c cells became similar to mESCs by further activation of genes associated with stem cell maintenance and gamete generation-related genes.

FIG. 6.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of three-fold changed genes from XiPS-7 cells to mESCs. (A) Upregulated genes (fold change >3; P value <0.01) in selected GO categories are shown. (B) KEGG pathways involved by upregulated genes in XiPS-7 cells (fold change >3; P-value <0.01). (C) Downregulated (fold change >−3; P value<0.01) in selected GO categories are shown. (D) KEGG pathways involved by downregulated genes in XiPS-7 cells (fold change >−3; P value<0.01). ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Differentiation potential of XiPS-7 and XiPS-7c cells

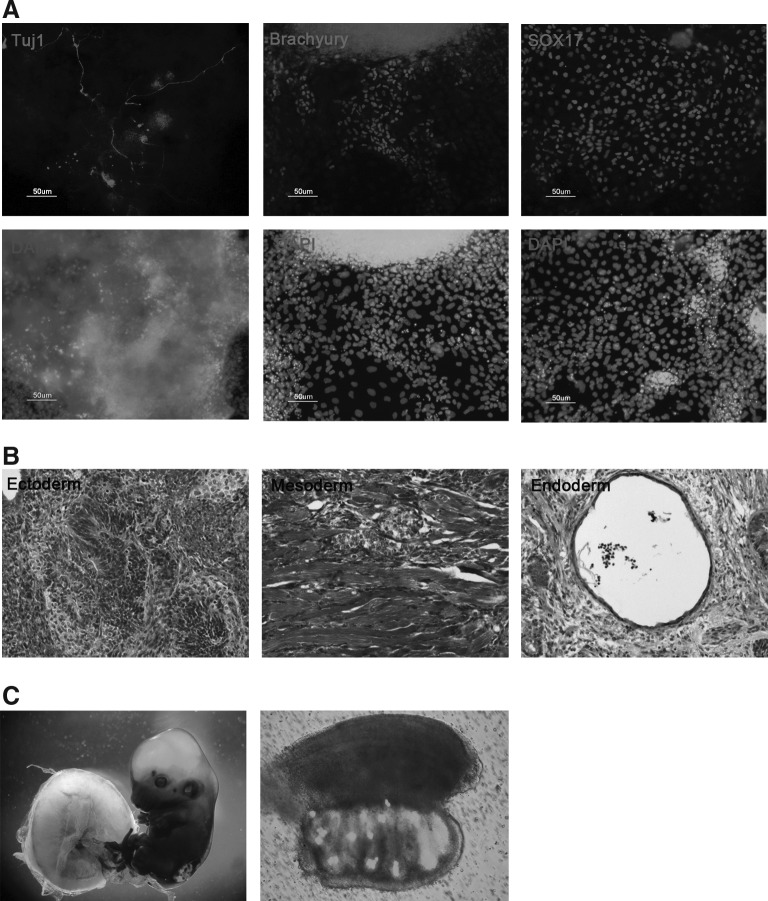

Next, we compared the differentiation potential of XiPS-7c and XiPS-7 cells. Although XiPS-7 cells did not efficiently form EBs (data not shown), XiPS-7c cells efficiently formed EBs and differentiated into cells positive for Tuj1 (ectoderm), Brachyury (mesoderm), and Sox17 (endoderm) (Fig. 7A). XiPS-7c cells formed teratoma-containing lineages of all three germ layers (Fig. 7B); mesodermal differentiation was rarely detectable in XiPS-7. Teratoma analysis revealed that XiPS-7 cells preferentially differentiated into endodermal and ectodermal lineages; teratomas contained mostly endodermal (gut-like and secretary epithelium mixed form) and ectodermal (neural rosettes) cell types (Supplementary Fig. S7A, B). Moreover, XiPS-7c cells contributed to germline chimera (13.5 dpc) after morula aggregation and transfer into the uterus of pseudopregnant mice (Fig. 7C), which was not observed in XiPS-7 cells (data not shown). These results suggest that XiPS-7 cells represent partially reprogrammed cells and XiPS-7c represent fully reprogrammed cells.

FIG. 7.

In vitro and in vivo differentiation potential of XiPS-7c cells. (A) In vitro differentiation potential of XiPS-7c cells in EB formation. Expression of Tuj1 (ectoderm), Brachyury (mesoderm), and Sox17 (endoderm) in differentiated XiPS-7c cells. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar=50 μm. (B) In vivo differentiation of XiPS-7c cells by teratoma formation. The tissues of all three germ layers, including ectoderm (neural rosette), mesoderm (muscle fibers), and endoderm (gut-like epithelium), were detected in XiPS-7c cell-derived teratoma sections. Original magnification 100×. (C) A chimeric embryo of XiPS-7c cells was stained with X-gal. XiPS-7c cells contribute to germline cell development (Oct4-GFP positive) in a 13.5 dpc male gonad. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Discussion

Since the discovery of somatic cell reprogramming by defined factors, various studies have focused on the technical development of iPSC establishment and mechanistic characterization of the sequential steps of reprogramming. To study the mechanism of reprogramming, previous studies analyzed intermediate cells before complete reprogramming; however, these intermediate cells are not in a specific stage of reprogramming but comprise a heterogeneous population containing cells in early- to late-stage reprogramming and of various transgenic modifications by random integration of reprogramming genes. In this study, we cultured intermediate cell lines, which were long-term expandable without expression of Oct4-GFP. These partially reprogrammed XiPS-7 cells formed flat colonies and did not express endogenous Oct4 and Sox2. Interestingly, XiPS-7 cells converted to fully reprogrammed iPSCs (XiPS-7c) in serum-free (SR-based) medium with bFGF. Typically, SR and bFGF are used in culture for mouse epiblast stem cells [37], human ESCs [38], and human iPS cell generation [7]; whereas bFGF supplementation leads to differentiation in mESCs [29,31]. However, according to recent studies, bFGF plays a positive role in mouse somatic reprogramming. Mouse iPSC colonies can be obtained when serum-based media is changed to SR-based media, including LIF [23] and derived in serum-based media in the presence of bFGF [35,39]. SR contains abundant vitamin C, which improves reprogramming efficiency when added to culture medium during reprogramming [40,41]. The combination of SR, bFGF, and N2 significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency and kinetics [34]. bFGF is also a crucial factor for the derivation and maintenance of human naïve pluripotent cells (human ESCs and iPSCs) [42]. Therefore, the role of bFGF in mESC differentiation should be reconsidered.

In GO analysis, we found that “stem cell maintenance,” “gamete generation,” and “M phase of meiotic cell cycle” were the most affected genes in XiPS-7 versus XiPS-7c cells. Therefore, we suggest that partially reprogrammed cells could be further reprogrammed to the pluripotent state by upregulation of stem cell maintenance- and gamete generation-related genes (Supplementary Table S4). In KEGG pathway annotation, “focal adhesion” and “ECM-receptor interaction” categorized the most affected genes in XiPS-7 cells. Recently, ECM regulation by bFGF has been found to be crucial for somatic cell reprogramming [39]. We suggest that bFGF could play a role in somatic cell reprogramming through downregulation of extracellular collagens.

In this study, the partially reprogrammed cells did not express core pluripotency genes Oct4 and Sox2, but expressed Nanog. Accordingly, the Nanog promoter region was demethylated, but the Oct4 promoter region was hypermethylated in XiPS-7 cells. These partially reprogrammed cells could maintain the intermediate state for more than 20 passages without expression of Oct4 and Sox2. Oct4 and Sox2 regulate Nanog expression in pluripotent stem cells [43,44]; however, in XiPS-7 cells, Nanog was independent of the Oct4 and Sox2 regulatory network. This phenomenon could be explained by a recent report suggesting that Nanog could be expressed in the inner cell mass of Oct4-knockout embryos [36]. The expression of endogenous Nanog mediates somatic cell reprogramming into the pluripotent state [19], and forced expression of Nanog overcomes the obstacles in somatic cell reprogramming by switching to serum-free medium with LIF, a culture condition that does not support maintenance of mESCs [20]. In this regard, we suggest that Nanog without Oct4 and Sox2 maintains the partially reprogrammed cell state and conversion to fully reprogrammed iPSCs from partially reprogrammed cells by switching from mESC culture conditions to SR-based media with bFGF. The long-term expandable partially reprogrammed cells may provide useful clues to understanding stepwise reprogramming.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Biomedical Technology Development Program and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (grant no. 20110019489 and 2013R1A1A2011394).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicting financial interest.

References

- 1.Takahashi K. and Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okita K, Ichisaka T. and Yamanaka S. (2007). Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 448:313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K. and Daley GQ. (2008). Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 134:877–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soldner F, Hockemeyer D, Beard C, Gao Q, Bell GW, Cook EG, Hargus G, Blak A, Cooper O, et al. (2009). Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell 136:964–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, et al. (2008). Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science 321:1218–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr., Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA. and Svendsen CN. (2009). Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature 457:277–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K. and Yamanaka S. (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araki R, Jincho Y, Hoki Y, Nakamura M, Tamura C, Ando S, Kasama Y. and Abe M. (2010). Conversion of ancestral fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 28:213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golipour A, David L, Liu Y, Jayakumaran G, Hirsch CL, Trcka D. and Wrana JL. (2012). A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell 11:769–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansson J, Rafiee MR, Reiland S, Polo JM, Gehring J, Okawa S, Huber W, Hochedlinger K. and Krijgsveld J. (2012). Highly coordinated proteome dynamics during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Rep 2:1579–1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R, Liang J, Ni S, Zhou T, Qing X, Li H, He W, Chen J, Li F, et al. (2010). A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 7:51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikkelsen TS, Hanna J, Zhang X, Ku M, Wernig M, Schorderet P, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R, Lander ES. and Meissner A. (2008). Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature 454:49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polo JM, Anderssen E, Walsh RM, Schwarz BA, Nefzger CM, Lim SM, Borkent M, Apostolou E, Alaei S, et al. (2012). A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell 151:1617–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Cheng AW, Itskovich E, Markoulaki S, Ganz K, Klemm SL, van Oudenaarden A. and Jaenisch R. (2012). Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell 150:1209–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sancho-Martinez I. and Izpisua Belmonte JC. (2013). Stem cells: Surf the waves of reprogramming. Nature 493:310–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan EM, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Park IH, Manos PD, Loh YH, Huo H, Miller JD, Hartung O, Rho J, et al. (2009). Live cell imaging distinguishes bona fide human iPS cells from partially reprogrammed cells. Nat Biotechnol 27:1033–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva J, Barrandon O, Nichols J, Kawaguchi J, Theunissen TW. and Smith A. (2008). Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol 6:e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sridharan R, Tchieu J, Mason MJ, Yachechko R, Kuoy E, Horvath S, Zhou Q. and Plath K. (2009). Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell 136:364–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva J, Nichols J, Theunissen TW, Guo G, van Oosten AL, Barrandon O, Wray J, Yamanaka S, Chambers I. and Smith A. (2009). Nanog is the gateway to the pluripotent ground state. Cell 138:722–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theunissen TW, van Oosten AL, Castelo-Branco G, Hall J, Smith A. and Silva JC. (2011). Nanog overcomes reprogramming barriers and induces pluripotency in minimal conditions. Curr Biol 21:65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318:1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szabo PE, Hubner K, Scholer H. and Mann JR. (2002). Allele-specific expression of imprinted genes in mouse migratory primordial germ cells. Mech Dev 115:157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blelloch R, Venere M, Yen J. and Ramalho-Santos M. (2007). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of drug selection. Cell Stem Cell 1:245–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okita K, Hong H, Takahashi K. and Yamanaka S. (2010). Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells with plasmid vectors. Nat Protoc 5:418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MJ, Choi HW, Jang HJ, Chung HM, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Scholer HR. and Do JT. (2013). Conversion of genomic imprinting by reprogramming and redifferentiation. J Cell Sci 126:2516–2524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, Ichisaka T. and Yamanaka S. (2008). Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science 322:949–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE. and Jaenisch R. (2007). In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature 448:318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maherali N. and Hochedlinger K. (2008). Guidelines and techniques for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 3:595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greber B, Wu G, Bernemann C, Joo JY, Han DW, Ko K, Tapia N, Sabour D, Sterneckert J, Tesar P. and Scholer HR. (2010). Conserved and divergent roles of FGF signaling in mouse epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niwa H, Ogawa K, Shimosato D. and Adachi K. (2009). A parallel circuit of LIF signalling pathways maintains pluripotency of mouse ES cells. Nature 460:118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I. and Smith A. (2003). BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell 115:281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ficz G, Branco MR, Seisenberger S, Santos F, Krueger F, Hore TA, Marques CJ, Andrews S. and Reik W. (2011). Dynamic regulation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse ES cells and during differentiation. Nature 473:398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ficz G, Hore TA, Santos F, Lee HJ, Dean W, Arand J, Krueger F, Oxley D, Paul YL, et al. (2013). FGF signaling inhibition in ESCs drives rapid genome-wide demethylation to the epigenetic ground state of pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 13:351–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Liu J, Han Q, Qin D, Xu J, Chen Y, Yang J, Song H, Yang D, et al. (2010). Towards an optimized culture medium for the generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. J Biol Chem 285:31066–31072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Stefano B, Buecker C, Ungaro F, Prigione A, Chen HH, Welling M, Eijpe M, Mostoslavsky G, Tesar P, et al. (2010). An ES-like pluripotent state in FGF-dependent murine iPS cells. PLoS One 5:e16092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G, Han D, Gong Y, Sebastiano V, Gentile L, Singhal N, Adachi K, Fischedick G, Ortmeier C, et al. (2013). Establishment of totipotency does not depend on Oct4A. Nat Cell Biol 15:1089–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA. and Vallier L. (2007). Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koivisto H, Hyvarinen M, Stromberg AM, Inzunza J, Matilainen E, Mikkola M, Hovatta O. and Teerijoki H. (2004). Cultures of human embryonic stem cells: serum replacement medium or serum-containing media and the effect of basic fibroblast growth factor. Reprod Biomed Online 9:330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiao J, Dang Y, Yang Y, Gao R, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Sun XF. and Gao S. (2012). Promoting reprogramming by FGF2 reveals that the extracellular matrix is a barrier for reprogramming fibroblasts to pluripotency. Stem Cells 31:729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esteban MA, Wang T, Qin B, Yang J, Qin D, Cai J, Li W, Weng Z, Chen J, et al. (2010). Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stadtfeld M, Apostolou E, Ferrari F, Choi J, Walsh RM, Chen T, Ooi SS, Kim SY, Bestor TH, et al. (2012). Ascorbic acid prevents loss of Dlk1-Dio3 imprinting and facilitates generation of all-iPS cell mice from terminally differentiated B cells. Nat Genet 44:398–405, S1–S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, Manor YS, Chomsky E, Ben-Yosef D, Kalma Y, Viukov S, Maza I, et al. (2013). Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature 504:282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuroda T, Tada M, Kubota H, Kimura H, Hatano SY, Suemori H, Nakatsuji N. and Tada T. (2005). Octamer and Sox elements are required for transcriptional cis regulation of Nanog gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 25:2475–2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodda DJ, Chew JL, Lim LH, Loh YH, Wang B, Ng HH. and Robson P. (2005). Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem 280:24731–24737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.