Abstract

Background: For patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, a bihormonal artificial endocrine pancreas system utilizing glucagon and insulin has been found to stabilize glycemic control. However, commercially available formulations of glucagon cannot currently be used in such systems because of physical instability characterized by aggregation and chemical degradation. Storing glucagon at pH 10 blocks protein aggregation but results in chemical degradation. Reductions in pH minimize chemical degradation, but even small reductions increase protein aggregation. We hypothesized that common pharmaceutical excipients accompanied by a new excipient would inhibit glucagon aggregation at an alkaline pH.

Methods and Results: As measured by tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence shift and optical density at 630 nm, protein aggregation was indeed minimized when glucagon was formulated with curcumin and albumin. This formulation also reduced chemical degradation, measured by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry. Biological activity was retained after aging for 7 days in an in vitro cell-based bioassay and also in Yorkshire swine.

Conclusions: Based on these findings, a formulation of glucagon stabilized with curcumin, polysorbate-80, l-methionine, and albumin at alkaline pH in glycine buffer may be suitable for extended use in a portable pump in the setting of a bihormonal artificial endocrine pancreas.

Introduction

Glucagon raises blood glucose levels through activation of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis,1 but its secretion in response to hypoglycemia is abnormal in type 1 diabetes.2 The inclusion of glucagon within a dual-hormone, closed-loop control system for treatment of type 1 diabetes limits hypoglycemic events.3–7 However, commercially available glucagon, a lyophilized solid, rapidly aggregates after reconstitution with water, forming high-molecular-weight complexes,8–10 making it unsuitable for extended use in a closed-loop system. Aggregated glucagon is cytotoxic at high concentrations,11,12 and its action in vivo is delayed compared with fresh glucagon.12 Methods that show promise for stabilizing glucagon include formulation in alkaline media,12 creation of mutant glucagon analogs,13 the use of surfactants to increase solubility at neutral pH,14 and the use of anhydrous solvents to minimize chemical interactions with water.15

Our previous work examined chemical degradation of glucagon at alkaline pH, which include deamidation and oxidation.16 At pH 9, glucagon aggregates more but degrades much less than at pH 10; therefore, the use of pH 9 would require the addition of anti-aggregation excipients. To address this issue, we report here on the effects of commonly used excipients and the novel use of curcumin. Curcumin is a polyphenol derived from Curcuma longa rhizomes that exhibits multiple biological actions17–22 and has shown promise in reducing aggregation of neurodegenerative peptides important in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.23–30

In this report, we undertook a series of experiments that examined the pH dependence of glucagon aggregation, the effects of single and multiple excipients to block glucagon aggregation, the biological activity of formulations in a cell-based bioassay, and the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) behavior of fresh and aged stabilized glucagon in swine.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

l-Arginine, anhydrous sodium sulfite, anhydrous d-(+)-lactose, anhydrous glycerol, polysorbate-80, hydrochloric acid, anhydrous d-trehalose, trimethylamine N-oxide dihydrate, curcumin, thioflavin T (ThT), HyClone (Logan, UT)-modified Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline, curcumin, bovine serum albumin, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (San Jose, CA). Human serum albumin (HSA), 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, l-methionine, and dimethyl sulfoxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Polyvinylpyrrolidone was kindly donated by BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany) (Kollidon® 17 PF) and ISP Technologies (Wayne, NJ) (Plasdone® C17). Native human glucagon was synthesized by AmbioPharm, Inc. (Beech Island, SC) as reported previously.16 The peptide was purified to >99% and shipped as a lyophilized solid. Reagents were of highest purity available.

Sample formulation and aging

Stock glycine buffer was pH-adjusted with sodium hydroxide. The final concentration of both glucagon and HSA was 1 mg/mL. Prior to its use, solutions were passed through a 0.2-μm (pore size) polyvinylidene difluoride filter. Curcumin-containing solutions were formulated with gentle heating to bring curcumin into solution without the use of a solvent.31 A stock glycine buffer was diluted to approximately 80% of the final volume, brought to a pH of approximately 12, and then heated to 95–100°C. Curcumin was added to the solution and allowed to stir at 4°C until the solution reached room temperature (approximately 30 min). The pH was then brought to 9 using dilute hydrochloric acid, and excipient solutions were added. The solution was then brought to the final volume, glucagon and/or HSA was added, and the resultant mixture was passed through a 0.2-μm (pore size) polyvinylidene difluoride filter into a glass vial, which was then sealed. For optical studies (tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence [TIF], optical density at 630 nm, and transmission electron microscopy), a very low concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (0.5% vol/vol) was used to assist in solubilizing the curcumin.

All formulations were placed into a static 37°C incubator for the aging period. Unaged samples were immediately placed into a −20°C freezer. After aging was completed, the samples were frozen at −20°C until analysis.

Assays for peptide aggregation

The following assays were used to assess the effect of pH on glucagon aggregation and the ability of excipients to reduce aggregation.

ThT fluorescence assay

ThT fluorescence quantifies protein aggregation.32 A ThT stock solution was prepared by adding 8 mg of solid ThT to 10 mL of HyClone Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and shaking overnight in the absence of light. To prepare the working solution, the stock solution was passed through a 0.2-μm (pore size) filter to remove insoluble particulates from the ThT solution, then diluted 1:50 with HyClone Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline, and used immediately. For analysis, 10 μL of sample or blank was pipetted into a black 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) followed by addition of 200 μL of the ThT working solution to each well. A SpectraMax® Gemini™ microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) was used with excitation/emission wavelengths of 442/482 nm.

TIF assay

It has previously been shown upon aggregation of glucagon that tryptophan-25 experiences a blue-shift that can be used to assess overall peptide aggregation.8 Tryptophan-25 is located in a C-terminal hydrophobic patch that has been implicated in glucagon aggregation so we believe this assay is suitable because tryptophan-25 is most likely involved in glucagon aggregation and undergoes this blue-shift. As the peptide aggregates, there is increasing signal at 320 nm and decreasing signal at 350 nm. For analysis, excitation was at 280 nm, and the end point (TIF shift) was emission at 320 nm minus emission at 350 nm.

It has been reported that ThT assays cannot be used for curcumin-containing solutions because of optical interference from curcumin33 and other small fluorescent organic molecules34 due to curcumin's absorbance at 425 nm, a region similar to the emission wavelengths of aggregate-bound ThT. To verify this effect, we obtained samples of highly aggregated glucagon and carried out ThT assays with this material alone and immediately after mixing with 1 mM curcumin. When curcumin was added to this sample, the ThT data immediately showed a large (66%) loss of signal, indicating quenching by curcumin. The same experiment using the TIF assay showed no loss of signal (the TIF spectrum is much lower than curcumin absorbance). Thus, for curcumin experiments, we report TIF shift but not ThT data.

Optical density at 630 nm

When glucagon aggregates, it forms insoluble gels that impart cloudiness to solutions and can be measured by light scattering or light obscuration.14 By measuring the optical density at 630 nm, absorbance due to curcumin is minimized. Into a clear 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One), 200-μL samples of sample or blank were aliquoted, shaken gently, and read at 630 nm in an Epoch™ ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Data were corrected for path length differences among wells.

Effect of surfactant on protein stability and solubility

To assess the effect of polysorbate-80 on glucagon solubility, a Bradford protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was performed using 0%, 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 2.5%, and 5% (vol/vol) of polysorbate-80 concentrations. The concentration of polysorbate-80 required was defined as the lowest concentration necessary to reach a total protein concentration in the formulation of 2 mg/mL.

Fluorescence bioassay: protein kinase A

The glucagon bioassay used for these experiments uses Chinese hamster ovary K1 cells that stably overexpress the human glucagon receptor and also express an enhanced green fluorescent protein–protein kinase A fusion protein reporter molecule,35 as previously reported.16,36 In brief, after overnight culture, the cells were exposed to serially diluted glucagon in culture medium without antibiotics for 30 min at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed in 10% formalin for 20 min, washed, labeled with 1 μM Hoechst 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min, and imaged with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO), and data were analyzed with Slidebook version 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Loss of fluorescence is the measure of the cellular response to glucagon. The 50% effective concentration (EC50), a metric of potency (in pg/mL), was determined as the midpoint between the 100% plateau and the response floor using a four-parameter logistic model  in the XLfit software program.

in the XLfit software program.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

Glucagon formulated with different excipients was analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS). Samples were diluted to 1 μM in 1% formic acid from 1 mg/mL and held at 4°C until analysis. Ten picomoles of protein was injected into an Agilent 1100 high-performance liquid chromatography system fitted with a reverse-phase ZORBAX SB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). A mobile phase of 1% formic acid and a gradient of acetonitrile from 7.5% to 45% over a 60-min interval were used. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in a Thermo Fisher Scientific linear ion trap Velos™ instrument. Peptide mass spectrometry analysis and identification were performed using Xcalibur™ version 2.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Unmodified glucagon has a monoisotopic molecular mass of 3,480.6 Da. Detection of oxidized or deamidated glucagon was carried out by examining species that had a molecular mass increase of +16 or +1 Da, respectively. Other modifications were determined from the mass spectrum using Xcalibur or other proteomics tools. For all LCMS figures, retention time shift refers to setting unmodified glucagon retention time as 0 min (experimentally approximately 29.5 min). It should be noted that polysorbate-80 will saturate the detection signal when analyzed via LCMS. For this reason, we chose to analyze the final formulations without polysorbate-80 to learn about the chemical and physical degradation in our formulation.

Transmission electron microscopy

A 10-μL sample including 1 mg/mL glucagon with or without 1 mM curcumin and 1 mg/mL HSA (pH 9) was deposited on a copper grid, stained with 1.33% uranyl acetate for 45 s, air-dried, and viewed at 100 kV using a Philips/FEI (Hillsboro, OR) CM120 microscope. Images were collected as 1,024×1,024 pixel files on a Gatan (Pleasanton, CA) 794 CCD multiscan camera and converted into TIFF images (Image-J software; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Sixty images for each condition were each examined by three blinded observers.

Yorkshire swine study: PK and PD evaluation

Each of 11 Yorkshire pigs was tested with two formulations of glucagon over several months for a total of 22 experiments. The Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol (ID number IS00001790). The formulations tested were unaged curcumin-stabilized glucagon and curcumin-stabilized glucagon aged for 7 days at 37°C. Overnight fasted pigs were sedated using tiletamine/zolazepam (Telazol®; Zoetis, Florham Park, NJ) and atropine, weighed, intubated, and maintained on 1.5–2.0% isoflurane and oxygen. In order to block endogenous pancreatic α- and β-cell function, each animal was given octreotide (3 μg/kg/h, i.v.) starting 40 min prior to the glucagon bolus. The glucagon dose was given subcutaneously at time 0 in a dose of 2 μg/kg. Venous blood glucose was monitored in real time every 10 min for 2 h (HemoCue® 201 analyzer; HemoCue, Cypress, CA). Venous blood samples were also drawn periodically for glucagon and insulin concentration measurement. Glucagon was analyzed by radioimmunoassay (EMD Millipore, St. Charles, MO), and insulin was assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

For PK and PD data, four parameters were determined: the maximum change in glucagon concentration or glucagon effect, time to early half-maximum concentration or effect, time to maximum change of concentration or effect, and 60-min incremental area under the curve of concentration or effect. PD data fit a normal distribution, and thus parametric statistics were applied to PD data analysis. PK data were significantly skewed (24 of 28 tests) for each metric; for this reason, we analyzed PK data by nonparametric median-based statistics.

Statistical tools

PD data were analyzed by a two-sided Student's t test, whereas PK data was analyzed by a Mann–Whitney U test, both with significance defined as α<0.05. Results are presented as mean±SEM values (PD) or median values with 25th and 75th percentiles (PK).

Results

Glucagon aggregation increases substantially below pH 9.7

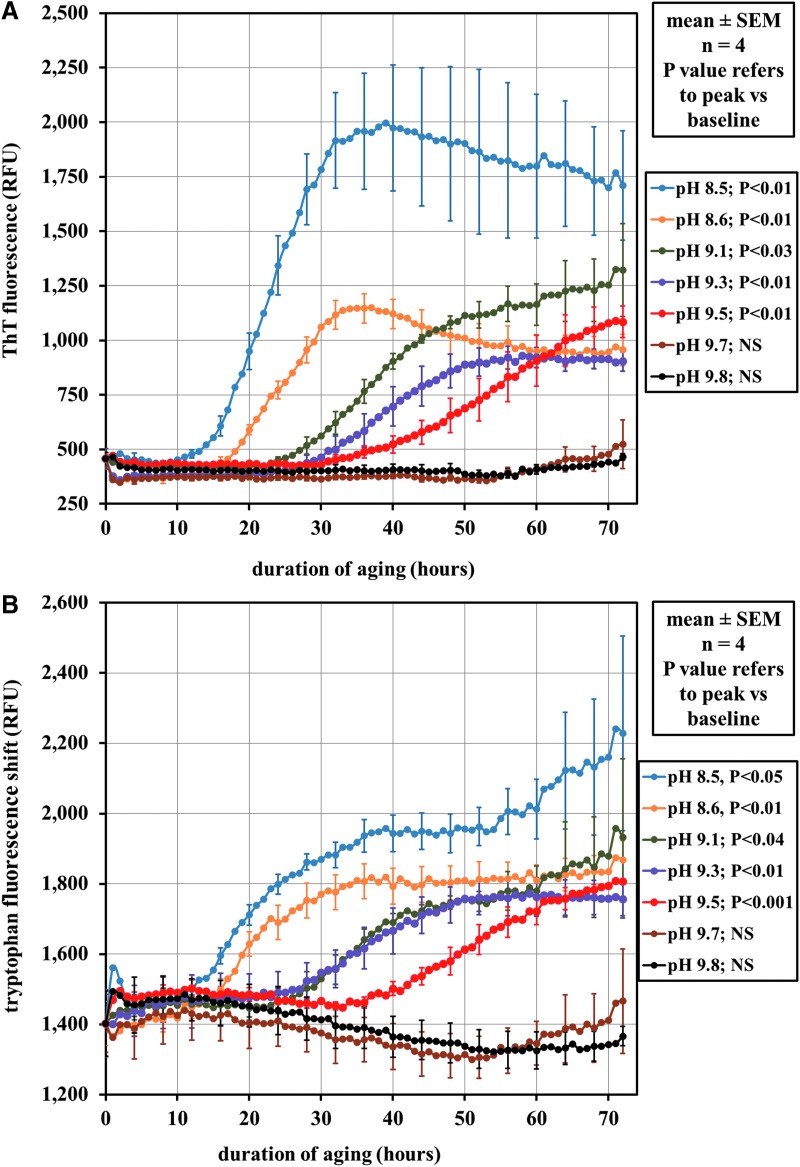

The effect of pH (8.5–9.8) on aggregation kinetics over a 72-h period is shown in Figure 1A for ThT and in Figure 1B for TIF shift. The more alkaline samples (pH 9.7 and 9.8) showed very little aggregation by ThT or TIF over this time period. However, substantial changes in ThT and TIF shift were found within a narrow pH range; there was little evidence of aggregation at pH 9.7, but substantial aggregation occurred at pH 9.5. After reaching a maximum, the fluorescence tended to decline or plateau, especially for ThT.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence spectroscopy of glucagon aggregation in the pH range 8.5–9.8 over a 72-h interval at room temperature. (A) Aggregation was assayed by the use of the thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescent probe that quantitatively binds to aggregated protein. Between pH 9.5 and 9.7, aggregation was greatly reduced, with the peak fluorescence at pH 9.7 and 9.8 showing no significant difference in fluorescence from time=0 h. NS, difference not significant; RFU, relative fluorescence units. (B) Aggregation was assayed by measuring the tryptophan fluorescence at 320 minus fluorescence at 350 nm. Results similar to (A) were found; there was a definite shift in aggregation between pH 9.5 and 9.7 with pH 9.7 and 9.8 peak fluorescence shift showing no significant difference from time=0 h. n refers to replicates per plate tested.

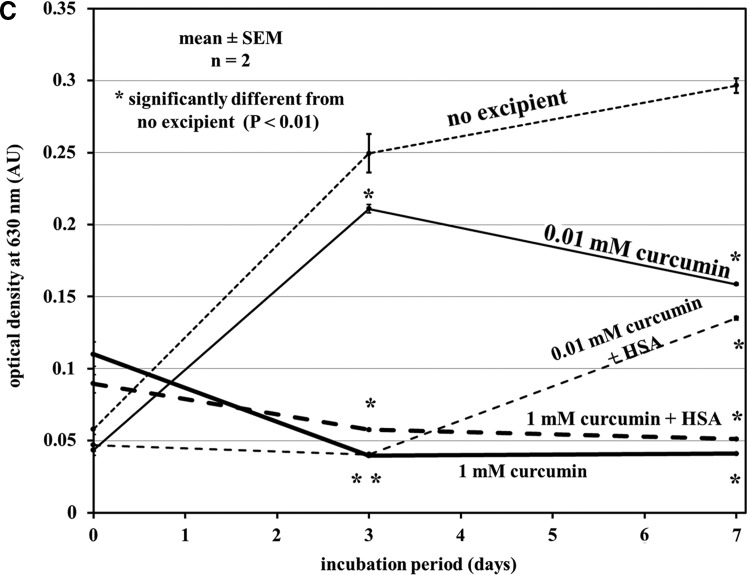

Curcumin, HSA, and polysorbate-80 inhibit glucagon aggregation

In the TIF assay, the presence of polysorbate-80, HSA, and curcumin in glucagon aged for 7 days at 37°C greatly reduced aggregation (Fig. 2A and B). Curcumin at 1 mM substantially reduced aggregation, but 0.01 mM curcumin was not effective. When HSA was added to preparations with curcumin, aggregation at 3 and 7 days was significantly reduced compared with no excipient.

FIG. 2.

Aggregation assays showing the effect of excipients to inhibit aggregation. RFU, relative fluorescence units. (A) Tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence shift showing both human serum albumin (HSA) and polysorbate-80 reduce aggregation over a period of 7 days, whereas l-methionine does not help aggregation significantly. (B) High levels of curcumin at pH 9 minimize glucagon aggregation and are significantly lower in aggregation after 7 days at 37°C compared with glucagon without excipient at pH 9. The benefit of HSA was also seen because 0.1 mM curcumin by itself shows no major benefit, but when aged along with HSA there was significantly lower aggregation at 3 and 7 days of aging at 37°C. (C) Solution optical density measured at 630 nm, which related to physical gelation of glucagon. AU, absorbance units. The trends seen in (C) were similar to those seen in (B). n refers to replicates per plate tested.

Figure 2C shows measurements of optical density at 630 nm on the same samples as in Figure 2B. These data also demonstrate that the curcumin and HSA block age-related aggregation.

Transmission electron microscopy verifies the antifibrillation effect of curcumin

Glucagon samples were aged for 14 days rather than 7 days to allow more time for visible aggregates to occur. Upon examination of the aggregates formed in alkaline glucagon, it was seen that under these conditions, glucagon forms distinct yet short fibrils, as seen in Figure 3A. All observers identified fibrils in samples without excipient, and none found fibrils in samples containing curcumin and HSA. For glucagon without excipient, the three observers found fibrils in seven of 60, eight of 60, and eight of 60, respectively (P<0.001, Fisher's exact test). The Fleiss κ result for the observers was 0.86 (z=20), indicating very high concordance among the three observers.

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs at ×4,800 magnification: (A) 1 mg/mL glucagon without curcumin aged for 14 days shows densely packed fibrils, and (B) 1 mg/mL glucagon with curcumin aged for 14 days shows an absence of fibrils.

Figure 3A shows glucagon fibrils without excipient after 14 days. Figure 3B shows absence of fibrils in a specimen in which glucagon was aged with curcumin and HSA. Each of these images is representative of the entire set of analyzed micrographs.

Glucagon oxidation from curcumin

LCMS measured glucagon chemical degradation during aging. Minimal chemical degradation occurred when glucagon was aged for 7 days at pH 9 at 37°C, as seen in Figure 4B, although aggregation was marked under this condition. When curcumin was added at 1 mM to block aggregation, almost complete oxidation of glucagon occurred along with modest deamidation (Fig. 4C). To avoid oxidation of glucagon, l-methionine (1 mg/mL) was added. The l-methionine markedly reduced oxidation, although adducts of glycine and glucagon appeared within the chromatogram, seen at +1 to 2 min (Fig. 4D). High-performance liquid chromatography showed minimal chemical or physical degradation due to polysorbate-80 (data not shown). Oxidation at the level found after l-methionine addition does not seem to affect aggregation of glucagon, there still is significant aggregation occurring as shown by TIF (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/dia).

FIG. 4.

High-performance liquid chromatograms with mass spectrometry of different glucagon preparations. (A) Unaged glucagon at pH 9 shows a well-defined peak that is identified as native glucagon. Minor amounts of chemical degradation may have occurred as a result of long-term storage. (B) Native glucagon aged for 7 days at 37°C at pH 9 shows minimal chemical degradation (although this preparation was markedly aggregated as shown in Figs. 1 and 2). (C) Addition of curcumin causes near complete oxidation of glucagon. (D) Addition of l-methionine to the glucagon/curcumin solution prevents the curcumin-induced oxidation, although there are additional products that are formed at approximately +1.5 min that can be attributed to glycine adducts (mass equal to glycine added to glucagon).

Other excipients to stabilize curcumin and polysorbate-80 to increase glucagon solubility

Polysorbate-80 was successful in increasing solubility of glucagon and curcumin. Without polysorbate-80, the protein (glucagon and HSA) was found to precipitate at 4°C and −20°C. The addition of polysorbate-80 yielded a clear solution without precipitate. This finding was confirmed by ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometric analysis for curcumin and the Bradford assay for protein content, both of which showed maintenance of initial concentration (Supplementary Fig. S2). Polysorbate-80 has the added benefit of helping to reduce aggregation as well, as shown in Figure 2A (Supplementary Fig. S3 displays non-baseline corrected data). HSA was added because of reports that common mammalian serum proteins, particularly albumin, stabilize curcumin.37,38

Curcumin reduces age-induced potency loss in glucagon

Glucagon formulated at pH 9 and aged for 7 days at 37°C showed a significant loss of potency (increased EC50) versus unaged glucagon (P<0.001) (Fig. 5A) in a cellular bioassay for glucagon receptor activation. In contrast, when the curcumin-stabilized glucagon formulation (including 1 mg/mL HSA, 1 mg/mL l-methionine, and 0.5% [vol/vol] polysorbate-80) was tested, the EC50 shift between the aged and unaged preparations was much smaller and not significantly different from one another (P=0.33). In addition, the increase in EC50 over time was significantly greater in the glucagon formulation without excipient than in the curcumin-stabilized glucagon formulation (P=0.008). It should also be noted that reagent controls without glucagon do not elicit any biological response (i.e., EC50 is infinite).

FIG. 5.

Glucagon bioassay based on protein kinase A activation. Dose–response curves show 50% effective concentration (EC50) shifts. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. (A) 1 mg/mL glucagon prepared at pH 9 and aged for 7 days at 37°C shows a significant change in potency. (B) 1 mg/mL glucagon prepared with 1 mM curcumin, 1 mg/mL human serum albumin, 1 mg/mL l-methionine, and 0.5% (vol/vol) polysorbate-80 shows no significant change in potency over 7 days aged at 37°C. The fold change in potency for the curcumin-stabilized glucagon shows significant difference from the pH ninefold change in potency. n refers to the number of individual experiments performed.

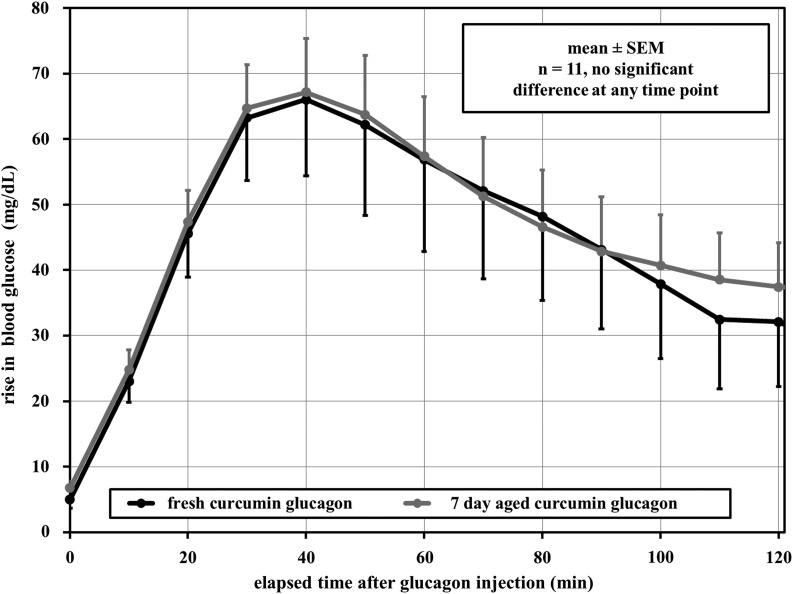

Evaluation of curcumin-stabilized glucagon in swine

Yorkshire pigs were given subcutaneous injections of unaged curcumin-stabilized glucagon and aged curcumin-stabilized glucagon (the same formulation as in the cell bioassay) to measure PK/PD. Insulin levels stayed within 10–20% of baseline over the 3-h period of each study, demonstrating that the insulin response to hyperglycemia was appropriately inhibited by octreotide (data not shown). Figure 6 shows the change in blood glucose level rise over time for the two preparations. In terms of the hyperglycemic responses, there were no significant differences between fresh and aged curcumin-stabilized preparations at any time point.

FIG. 6.

Mean pharmacodynamics effects of different glucagon formulations given subcutaneously in Yorkshire pigs. Results from fresh curcumin-treated glucagon and results from 7-day aged curcumin-treated glucagon show no significant difference at each time point. n refers to the number of individual swine tested.

Additional metrics, including early average time to 50% of maximum before peak is reached and average time to maximum change, were also used to compare the glucose and plasma glucagon concentrations (Table 1). Because each of the 11 animals was given both formulations, paired tests were used; no differences between unaged versus aged formulation were seen. Additionally, no edema or erythema was seen in any swine over the interval of the examination (180 min).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics Metrics Determined from This Study

| Curcumin glucagon | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric (n=11) | Fresh | 7 day aged |

| Venous glucose (PD) (mean±SEM) | ||

| Max Δ (mg/dL) | 70±12 | 70±8 |

| Early t50% (min) | 15±1 | 14±1 |

| tmax (min) | 40±4 | 36±2 |

| 60-min AUCinc (min×mg/dL) | 2,801±501 | 3,002±339 |

| Plasma glucagon (PK) [median (25%, 75%)] | ||

| Max Δ (pg/mL) | 278 (220, 586) | 359 (259, 2,596) |

| Early t50% (min) | 9 (4, 12) | 5 (3, 7) |

| tmax (min) | 30 (20, 70) | 20 (20, 30) |

| 60 min AUCinc (min×pg/mL) | 12,611 (9,188, 20,491) | 14,993 (10,758, 114,577) |

Pharmacodynamics (PD) data were analyzed according to parametric statistics. Pharmacokinetics (PK) data were significantly skewed (24 of 28 tests) for each metric and analyzed by nonparametric statistics. There were no significant differences among both preparations.

60 min AUCinc, incremental area under the curve for metric; Early t50%, average time to 50% of maximum before peak is reached; Max Δ, average maximum change in venous glucose or plasma glucagon; tmax, average time to maximum change.

Effect of a variety of excipients on glucagon degradation and bioactivity

Many other excipients were tested for their potential to stabilize glucagon (Supplementary Table S1). Several excipients led to substantial deamidation and/or oxidation. Some caused chain cleavage or adduct formation (data not shown). The potency loss for several (l-arginine, β-cyclodextrin, and trimethyl amine N-oxide) was marked. In general, these excipients were ineffective in blocking aggregation (data not shown) and were excluded from further testing.

Discussion

Effect of curcumin on glucagon aggregation

We chose to test curcumin as an excipient for glucagon formulation because of its ability to reduce amyloid fibrillation in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.23–30 We added HSA to the solutions because of published evidence that it reduces spontaneous degradation of curcumin.37 We found that high concentrations of curcumin yielded a solution that was free of assayable aggregates, even without the addition of HSA. The persistent benefit of the high concentrations of curcumin is likely due to weak bonding interactions that disrupt the secondary structure characteristic of protein aggregates. Curcumin contains two aromatic moieties that would participate in π–π electron stacking with aromatic amino acids.27 The aromatic residues of glucagon are located near hydrophobic patches at the N- and C-termini (residues 6–10 and 23–27), which likely contribute to its tendency toward aggregation.39 The phenyl moieties of curcumin could disrupt self-association (aggregation) of these hydrophobic patches. In addition, Reinke and Gestwicki40 postulated that the conformational shape and the length of the hydrocarbon linker within curcumin assist in disrupting amyloid formation.

Curcumin leads to glucagon oxidation, which is inhibited by l-methionine

The pro-oxidant activity of curcumin19 probably accounts for the glucagon oxidation found by LCMS. As we found, Met27 is oxidized during the aging of glucagon.16 l-Methionine, which likely undergoes sacrificial oxidation, markedly reduced glucagon oxidation. The glycine adducts that form with l-methionine are not well understood; it is possible that other phenolics may stabilize glucagon without formation of these adducts.

Stabilized glucagon is bioactive in vitro and in vivo

Given glucagon aggregation delays its absorption12 and leads to cytotoxicity,11 aggregation must be addressed. In the cell-based bioassay, there was significant loss of potency in aged versus unaged glucagon without excipient. In contrast, aged curcumin-stabilized glucagon only exhibited a minimal, nonsignificant loss of potency. This finding strongly suggests that curcumin maximizes the glucagon monomeric (bioactive) conformation.

Aged and unaged curcumin-stabilized preparations of glucagon were also tested in octreotide-treated pigs; no significant difference between unaged and aged stabilized glucagon in PK or PD parameters was found, which suggests minimal loss of bioactive glucagon. The 2 μg/kg dose we gave to pigs is a submaximal dose, much different than the massive dose in the human hypoglycemia kit. For this reason, we believe that if there was degradation of glucagon in the 2 μg/kg dose, there would be loss of the biological effect (we observed no PK or PD loss). In fact, one reason that we chose this submaximal dose of the glucagon for the pig study was so that we could detect a loss of effect if there was degradation.

Current commercially available preparations of glucagon are acidic, lyophilized formulations that must be used immediately after reconstitution in order to minimize exposure to aggregated glucagon. Our studies here suggest that formulating glucagon at a pH of 9 with the addition of curcumin and albumin may well extend the usage period to 7 days, which would be useful in a bihormonal artificial endocrine pancreas system.

Our previous work described several chemical degradations of glucagon at alkaline pH during aging.16 Acidic glucagon formulations form a variety of fibrillar polymorphisms,10 but glucagon formulated at pH 10 remains monomeric.12 Although glucagon, like other hormones, is stored in amyloid fibrils in its membrane-bound secretory granules,41 aggregation of the drug must be minimized for exogenous administration via a pump.

pH dependence of glucagon aggregation

Although glucagon is highly degraded at pH 10, less physical and chemical degradation occurs at pH 9.16 Here we extend those findings and show that there is a narrow zone between pH 9 and 10 at which and below which glucagon aggregates. As pH is lowered, aggregation occurs more rapidly; at pH 8.5, glucagon begins to aggregate within 12–14 h. Although the alkaline range might seem unusual for drug formulation, there are many pharmaceuticals formulated in this range, such as amitriptyline and its metabolite nortriptyline, trimipramine, mianserin, mirtazapine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, levomepromazine, quetiapine, ketobemidone, tramadol, alimemazine, and metoprolol.42 Most are administered orally, but amitriptyline, levomepromazine, ketobemidone, tramadol, and metoprolol can be formulated as injectable solutions, with levomepromazine specifically listed as subcutaneous. In addition, we found that a solution of albumin when prepared at a pH of 10 did not induce more discomfort in humans compared with a pH of 7.443; speed of injection was a contributing factor. Although not tested in this study, this earlier finding suggests that the current formulation of glucagon (pH 9) may be pain-free upon injection.

Implications, limitations, and future studies regarding curcumin-stabilized glucagon

Although additional regulatory work is needed for verification, it appears that stabilization of glucagon by curcumin might well be a promising step for treatment of persons with type 1 diabetes, because the formulation was active in vitro and in vivo.

Limitations of this study include lack of shelf-life stability experiments to examine long-term stability. Another limitation is that curcumin is relatively uncharacterized when it comes to the pharmaceutical industry. Product searches revealed that its primary use currently is in unregulated nutraceuticals. The regulatory approval process for curcumin might well be cumbersome. Related compounds (congeners)18 may facilitate a faster regulatory process and may have increased anti-aggregation attributes compared with curcumin. Additionally, in terms of our in vivo studies, we only studied one dose; multiple doses will be needed to measure power and potency. Finally, we would note that absorption of glucagon in vivo may be affected by the alkaline pH of our formulation, and the use of this alkaline suspension may potentially decrease absorption of glucagon compared with the acidic formulation; this comparison will need to be performed if pharmaceutical development is to occur.

In conclusion, we have described the development of a stabilized formulation of an amyloid-forming peptide, glucagon, through the use of curcumin, albumin, an antioxidant, and a surfactant, buffered to pH 9. This preparation shows minimal protein aggregation, minimal chemical degradation, and high activity both in a cell-based bioassay and in live pigs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the JDRF for grant 17-2012-15 that supported this research. LCMS was performed at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Proteomics Shared Resource with partial support from National Institutes of Health core grants P30EY010572 and P30CA069533. Bioassay imaging was performed at the Oregon National Primate Research Center Imaging and Morphology Core supported by National Institutes of Health core grant P51OD011092. Electron microscopy was performed at the Multi-scale Microscopy Core with technical support from the OHSU-FEI Living Lab and the OHSU Center for Spatial Systems Biomedicine. Glucagon and insulin immunoassays were performed by the OHSU Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute Core Lab supported by NCRR/NCATS-funded CTSA grant UL1TR000128. P.A.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant 5T32DK007674, and J.E.Y. was supported by National Institutes of Health K23 award DK090133. Special thanks to Ashley E. White from the Oregon National Primate Research Center for bioassay work, Dr. Claudia Lopez of OHSU for her assistance in transmission electron microscopy studies, Traci Schaller of OHSU for her assistance with pig studies, Katrina Ramsey of OHSU for statistical help, and Anna Duell for assistance in manuscript review.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing interests exist for the work described.

N.C. and W.K.W. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study. They take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. W.K.W., J.R.C., M.A.J., N.C., J.E.Y., and C.T.R. Jr. conceived of and planned the project. N.C., C.P.B., J.E.Y., P.A.B., M.A.J., L.L.D., G.L.L., M.E.B., and J.M.C. researched and/or collected data. N.C., M.A.J., C.P.B., J.R.C., J.E.Y., L.L.D., C.T.R. Jr, J.M.C., and W.K.W. performed data analysis. N.C., M.A.J., J.R.C., C.T.R. Jr, and W.K.W. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jiang G, Zhang BB. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2003;284:E671–E678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryer PE: Minireview: glucagon in the pathogenesis of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in diabetes. Endocrinology 2012;153:1039–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Khatib FH, Jiang J, Gerrity RG, Damiano ER: Pharmacodynamics and stability of subcutaneously infused glucagon in a type 1 diabetic swine model in vivo. Diabetes Technol Ther 2007;9:135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward WK, Engle J, Duman HM, Bergstrom CP, Kim SF, Federiuk IF: The benefit of subcutaneous glucagon during closed-loop glycemic control in rats with type 1 diabetes. IEEE Sensors J 2008;8:89–96 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle JR, Engle JM, El Youssef J, et al. : Novel use of glucagon in a closed-loop system for prevention of hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1282–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Khatib FH, Russell SJ, Nathan DM, Sutherlin RG, Damiano ER: A bihormonal closed-loop artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:27ra. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haidar A, Legault L, Dallaire M, et al. : Glucose-responsive insulin and glucagon delivery (dual-hormone artificial pancreas) in adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized crossover controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 2013;185:297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen JS: The nature of amyloid-like glucagon fibrils. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:1357–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen JS, Dikov D, Flink JL, Hjuler HA, Christiansen G, Otzen DE: The changing face of glucagon fibrillation: structural polymorphism and conformational imprinting. J Mol Biol 2006;355:501–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen JS, Otzen DE: Amyloid—a state in many guises: survival of the fittest fibril fold. Protein Sci 2008;17:2–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onoue S, Ohshima K, Debari K, et al. : Mishandling of the therapeutic peptide glucagon generates cytotoxic amyloidogenic fibrils. Pharm Res 2004;21:1274–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward WK, Massoud RG, Szybala CJ, et al. : In vitro and in vivo evaluation of native glucagon and glucagon analog (MAR-D28) during aging: lack of cytotoxicity and preservation of hyperglycemic effect. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:1311–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chabenne JR, DiMarchi MA, Gelfanov VM, DiMarchi RD: Optimization of the native glucagon sequence for medicinal purposes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:1322–1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner SS, Li M, Hauser R, Pohl R: Stabilized glucagon formulation for bihormonal pump use. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:1332–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prestrelski S, Fang W-J, Carpenter JF, Kinzell J, inventors: Stable glucagon formulations for the treatment of hypoglycemia. U.S. Patent Application 20120046225. February23, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caputo N, Castle JR, Bergstrom CP, et al. : Mechanisms of glucagon degradation at alkaline pH. Peptides 2013;45:40–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maheshwari RK, Singh AK, Gaddipati J, Srimal RC: Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci 2006;78:2081–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand P, Thomas SG, Kunnumakkara AB, et al. : Biological activities of curcumin and its analogues (congeners) made by man and Mother Nature. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;76:1590–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Lazaro M: Anticancer and carcinogenic properties of curcumin: considerations for its clinical development as a cancer chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agent. Mol Nutr Food Res 2008;52(Suppl 1):S103–S127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aggarwal BB, Sung B: Pharmacological basis for the role of curcumin in chronic diseases: an age-old spice with modern targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009;30:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta SC, Prasad S, Kim JH, et al. : Multitargeting by curcumin as revealed by molecular interaction studies. Nat Prod Rep 2011;28:1937–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta SC, Patchva S, Koh W, Aggarwal BB: Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its miraculous biological activities. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2012;39:283–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim GP, Chu T, Yang F, Beech W, Frautschy SA, Cole GM: The curry spice curcumin reduces oxidative damage and amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse. J Neurosci 2001;21:8370–8377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ono K, Yoshiike Y, Takashima A, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M: Potent anti-amyloidogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects of polyphenols in vitro: implications for the prevention and therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem 2003;87:172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono K, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M: Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils in vitro. J Neurosci Res 2004;75:742–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, et al. : Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem 2005;280:5892–5901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porat Y, Abramowitz A, Gazit E: Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by polyphenols: structural similarity and aromatic interactions as a common inhibition mechanism. Chem Biol Drug Des 2006;67:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra S, Palanivelu K: The effect of curcumin (turmeric) on Alzheimer's disease: an overview. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2008;11:13–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad B, Lapidus LJ: Curcumin prevents aggregation in alpha-synuclein by increasing reconfiguration rate. J Biol Chem 2012;287:9193–9199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh PK, Kotia V, Ghosh D, Mohite GM, Kumar A, Maji SK: Curcumin modulates alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. ACS Chem Neurosci 2013;4:393–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurien BT, Singh A, Matsumoto H, Scofield RH: Improving the solubility and pharmacological efficacy of curcumin by heat treatment. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2007;5:567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson MR: Techniques to study amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Methods 2004;34:151–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hudson SA, Ecroyd H, Kee TW, Carver JA: The thioflavin T fluorescence assay for amyloid fibril detection can be biased by the presence of exogenous compounds. FEBS J 2009;276:5960–5972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noormagi A, Primar K, Tougu V, Palumaa P: Interference of low-molecular substances with the thioflavin-T fluorescence assay of amyloid fibrils. J Pept Sci 2012;18:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaccolo M, De Giorgi F, Cho CY, et al. : A genetically encoded, fluorescent indicator for cyclic AMP in living cells. Nat Cell Biol 2000;2:25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson MA, Caputo N, Castle JR, David LL, Roberts CT, Jr, Ward WK: Stable liquid glucagon formulations for rescue treatment and bi-hormonal closed-loop pancreas. Curr Diabetes Rep 2012;12:705–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung MH, Kee TW: Effective stabilization of curcumin by association to plasma proteins: human serum albumin and fibrinogen. Langmuir 2009;25:5773–5777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang YJ, Pan MH, Cheng AL, et al. : Stability of curcumin in buffer solutions and characterization of its degradation products. J Pharm Biomed Anal 1997;15:1867–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen JS, Dikov D, Otzen DE: N- and C-terminal hydrophobic patches are involved in fibrillation of glucagon. Biochemistry 2006;45:14503–14512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinke AA, Gestwicki JE: Structure-activity relationships of amyloid beta-aggregation inhibitors based on curcumin: influence of linker length and flexibility. Chem Biol Drug Des 2007;70:206–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maji SK, Perrin MH, Sawaya MR, et al. : Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science 2009;325:328–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amundsen I, Oiestad ÅM, Ekeberg D, Kristoffersen L: Quantitative determination of fifteen basic pharmaceuticals in ante- and post-mortem whole blood by high pH mobile phase reversed phase ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2013;927:112–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward WK, Castle JR, Branigan DL, Massoud RG, El Youssef J: Discomfort from an alkaline formulation delivered subcutaneously in humans: albumin at pH 7 versus pH 10. Clin Drug Investig 2012;32:433–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.