Abstract

This review will critically evaluate recent findings suggesting that embryonic stem cells and stem cells derived from adult tissues, including bone marrow and umbilical cord blood, may be utilized in repair and regeneration of injured or diseased lungs. This is an exciting and rapidly moving field that holds promise as a novel therapeutic approach for cystic fibrosis and other lung diseases. However, while early studies suggested substantial lung remodeling, particularly with bone marrow-derived cells, more recent findings suggest that engraftment of adult marrow-derived cells in lung is a rare event of uncertain significance. Most recently, it has been suggested that a more relevant role of adult marrow-derived stem cells in lung is modulation of local inflammatory and immune responses. This review will also describe recent advances in understanding of local stem and progenitor cells in lung and their roles in lung development and repair.

Keywords: lung, cystic fibrosis, stem cell, progenitor cell

1. Introduction

Recent reports have suggested that several cell populations derived from adult bone marrow, adipose tissue, placenta, amniotic fluid, or umbilical cord blood, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), stromal-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), and circulating fibrocytes, can localize to a variety of organs and acquire phenotypic and functional markers of mature organ-specific cells [1–3]. These exciting and provocative studies have provided a basis for attempts at stem cell therapies for a wide variety of diseases. However, whether the cells utilized in these studies were truly “stem” cells has not always been rigorously demonstrated and some of the studies are controversial [4]. Further, fusion of bone marrow-derived cells with resident organ cells, rather than phenotypic conversion of the marrow cells, has been demonstrated in several organs, notably liver and skeletal muscle [5,6]. Nonetheless, this phenomenon may still provide a viable therapeutic approach for treatment of lung and other diseases.

2. Lung Repair and Remodeling with Adult Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells

In lung, a growing body of work investigating whether both embryonic and adult stem cells can be utilized for repair or regeneration of injured lung has accumulated over the past approximate five years (Figure 1) [reviewed in 7–8]. Both mouse embryonic stem cells and MSCs derived from either adult mouse or human bone marrow or from human umbilical cord blood, can be induced to express markers of airway or alveolar epithelial phenotype in vitro [9–12]. In some cases, in vitro acquisition of functional phenotype characteristic of lung epithelium has been demonstrated as well. For example, MSCs obtained from bone marrow of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients and transduced ex vivo to express wildtype cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) partly corrected defective CFTR-mediated chloride conductance when co-cultured with primary airway epithelial cells obtained from CF patients [13]. These studies demonstrate the capacity of both embryonic and adult stem cells to acquire lung epithelial phenotype and provide proof of concept for potential therapeutic use.

Figure 1.

Schematic of endogenous, embryonic, and adult stem cells that potentially participate in lung development, injury, repair, and regeneration.

Parallel in vivo studies in mouse models have suggested that bone marrow-derived cells can localize to lung and acquire phenotypic markers of airway and alveolar epithelium, vascular endothelium, and interstitial cells [reviewed in 7,8]. In humans, lung specimens from clinical bone marrow transplant recipients demonstrate chimerism of both epithelial and endothelial cells [14,15]. Similarly, lung specimens from lung transplant patients demonstrate chimerism of lung epithelium [16,17]. A critical analysis of these studies was undertaken in a meeting co-sponsored by the National Heart Lung Blood Institute and by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, “Adult Stem Cells, Lung Biology, and Lungs Disease”, held at the University of Vermont in July 2005 [7]. As reviewed in that report, many of those studies were based on sex-mismatched transplantation and in situ demonstration of Y chromosome-containing donor marrow-derived cells in recipient lungs by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), followed by immunohistochemical phenotyping of the donor-derived cells [18]. However, as analytical techniques have improved, despite the earlier reports demonstrating substantial engraftment of lung epithelium with donor-derived cells, more recent reports demonstrate that only small numbers of transplanted adult marrow-derived cells engraft in recipient lungs, particularly in airway or alveolar epithelium [19–22]. This includes only rare engraftment and CFTR expression in airway epithelium following transplantation of adult marrow-derived cells containing wildtype CFTR to CFTR KO mice [21] (Figure 2). Comparable low level engraftment was observed in intestinal epithelium of CFTR KO mice following transplant with wildtype marrow-derived cells [23]. As such, many of the earlier findings suggesting more substantial engraftment are now felt to be technical artifacts. Thus at present, while airway and alveolar epithelial engraftment by marrow-derived cells does occur, it is a rare occurrence and not yet linked to potential therapeutic benefit.

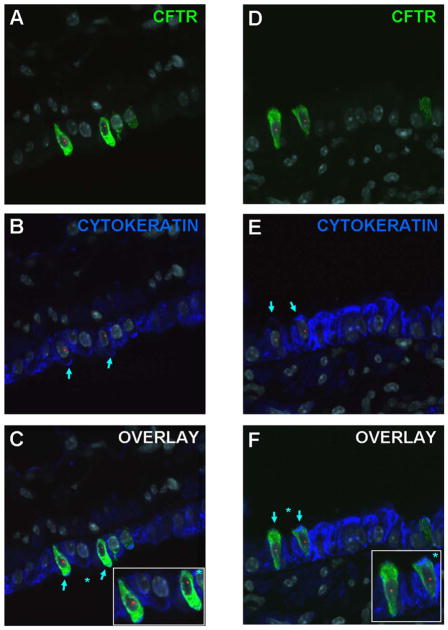

Figure 2.

Detection of Cftr expression in female Cftr KO mouse lungs following transplantation with male GFP stromal marrow cells. C,F) Donor derived (Y chromosome, red), Cftr positive (green), and cytokeratin positive (blue) cells, are indicated by light blue arrows in airway walls of lungs assessed 1 week after transplantation. Images from two separate recipient mouse lungs are depicted. A,D) and B,E): The same photomicrographs are shown after removal of the blue and the green channel respectively, to show co-expression of Cftr and cytokeratin by the donor-derived cells. Original magnification 1000X. Figure reprinted with permission from Loi et al Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2006; 173:171 [21].

More promising data currently exists for engraftment and regeneration of pulmonary vascular endothelium with endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). In rodent models of pulmonary hypertension, administration of EPCs has been demonstrated to result in vasculogenesis and correction of physiologic manifestations of pulmonary hypertension [24]. These studies have provided a basis for an active clinical trial evaluating autologous transplantation of EPCs for pulmonary hypertension, currently underway at the University of Toronto. This is the only active approved clinical trial in North America utilizing stem cells for treatment of lung diseases.

Circulating fibrocytes, adult marrow-derived cells that express both hematopoietic and myofibroblast markers, have been implicated in smooth muscle and myofibroblasts proliferation in both asthma and in pulmonary fibrosis [25–27]. This suggests a specific target for therapeutic intervention, ie., blocking recruitment and engraftment of fibrocytes in lung. However, as yet, there is little data demonstrating this can be effectively accomplished. Other populations of marrow-derived cells may yet be found to participate in structural lung remodeling or regeneration and are subjects of active study [28].

Several recent studies have demonstrated that culturing fetal lung cells in artificial three dimensional matrices results in formation of alveolar-like structures (28–29). This suggests that culture of stem cells in an artificial scaffolding in medium conducive to lung epithleial development may be a robust means of lung regeneration than achieved with routine tissue culturing [29–33].

Fusion of marrow-derived cells with skeletal muscle fibers and with hepatocytes has been well described. However, while adult marrow-derived MSCs can be induced to fuse with airway epithelial cells in vitro, in vivo studies have demonstrated this to be a rare phenomenon [34–35].

2. Lung Repair and Remodeling with Embryonic Stem Cells

Several studies have demonstrated that mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells can be induced to express pro-surfactant B, a marker of type 2 alveolar epithelial cells (9–10). Further, exposure of mouse ES cells to dissociated fetal lung cells induces pseudoglandular formation and surfactant protein C expression [36]. In one notable study, mouse embryonic stem cells cultured at air-liquid interface formed a pseudostratified epithelium resembling mouse tracheal epithelium [37]. These studies demonstrate the capacity of ES cells to acquire airway epithelial phenotype. Comparable studies with human ES cells are limited in the United States due to current restrictions on human ES cell use. A human deltaF 508 embryonic stem cell line has been established in England [38]. These cells exhibit normal morphology and protein expression compared with other ES cell lines but have not been studied in detail.

3. Lung Repair and Remodeling with Adult Stem Cells Obtained From Other Sources

Umbilical cord blood has long been utilized as a source of hematopoietic stem cells used in clinical bone marrow transplantation. Recently, it has been demonstrated that MSCs isolated from human umbilical cord blood can be induced to express markers of airway epithelium including CFTR [11]. Another population of cells obtained from human umbilical cord blood, multi-lineage progenitor cells, can be induced in culture to express surfactant protein C [12]. MSCs isolated from amniotic fluid have been utilized in studies evaluating tracheal repair and recently have been demonstrated also to structurally engraft in other parts of lung [33]. Comparably, MSCs from adipose and placental tissue have been isolated and characterized and may also provide an alternative source of cells for potential lung regeneration [39–40].

4. Functional Effects of Adult Bone Marrow-Derived Cells in Lung

Nonetheless, despite rare engraftment of airway or alveolar epithelium, there are an increasing number of studies demonstrating a functional role of adult marrow-derived cells in mitigation of lung injury. This has been described in models of lung inflammation, emphysema, and fibrosis and has been observed with several cell populations including MSCs [41–45]. Notably, systemic administration of MSCs immediately after intratracheal bleomycin administration decreased subsequent lung fibrosis and collagen accumulation [43]. Conversely, circulating fibrocytes, may contribute to development of lung fibrosis [25–27]. The mechanisms for these effects are unknown but strongly suggest that marrow-derived cells can participate in lung injury and repair even in the absence of structural engraftment.

More recently, it has been demonstrated that intratracheal, rather than systemic, administration of adult marrow-derived MSCs can mitigate lung injury. Intratracheal administration of MSCs four hours after intratracheal endotoxin administration decreased mortality, pulmonary edema, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and MIP-1β compared to endotoxin-only treated mice [46]. There was little structural engraftment of airway or alveolar epithelium by the MSCs. Comparably systemic administration of MSCs to mice with bleomycin-injured lungs decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and levels of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in the lungs [43,44]. These results suggest that MSCs may have significant immunomodulatory effects in the lung. Whether these cells can be utilized to modulate airways inflammation in CF or alternatively whether engraftment of marrow or cord blood-derived cells in airways epithelium can be utilized to correct defective CF airways epithelium are areas of active study but as yet have not yielded any viable therapeutic strategies.

5. Recruitment of Adult Marrow-Derived Cells to Lung and Mechanisms of Phenotypic Conversion to Lung Epithelial or Interstitial Cells

The mechanisms by which marrow-derived or cord blood-derived cells are recruited to lung and acquire airway or alveolar epithelial phenotype are poorly understood. Pre-existing injury increases recruitment of adult marrow-derived cells to lung [7–8.21–28,41–45] suggests that chemotactic signals released by injured or re-modeling lung serve to attract marrow-derived cells. Soluble factors such as stromal derived factor (SDF-1, CXCL12) stimulate HSC mobilization and targeted tissue migration. Bleomycin increases lung expression of SDF-1 suggesting a role of this signaling pathway in recruitment of adult marrow-derived cells to lung (43). SDF-1 has also been implicated in recruitment of MSCs to liver and heart [47,48]. A number of other chemokine and angiogenic factors are also known to mobilize and recruit both HSCs and EPCs. Increased release of soluble factors as well as increased expression of tissue ligands to which HSCs and EPCs can bind occurs in a variety of lung injuries. Presumably this increases recruitment of HSCs and EPCs to lung but there is little direct data demonstrating this phenomenon [49–51]. Adult marrow-derived circulating fibrocytes exhibit chemotaxis in response to a number of ligands released from injured lung including SDF-1, CCL-2, and eotaxin [27,52–53]. Further, exposure of circulating fibrocytes to ligands upregulated in fibrotic lung injury including TGFβ-1 and endothelin-1 promote differentiation into a myofibroblast phenotype [27]. Human MSCs express receptors for several chemokines and cytokines including CXCR4 that might play a role in recruitment of MSCs to lung but there is little available information on the role of chemokines, cytokines, or other soluble factors in recruitment of MSCs to lung [43].

Similarly, expression of specific adhesion molecules or other proteins by injured or remodeling lung may be important for recruitment of adult marrow-derived cells. HSCs and EPCs express several cell surface adhesion molecules (CD44, VCAM-1, ICAM-1) that can interact with corresponding tissue selectins and matrix proteins to mediate tissue binding [54]. Adult marrow-derived human MSCs express cell surface adhesion molecules including VCAM-1 and CD-44. In experimental bleomycin-induced lung injury in mice, increased expression of the CD44 ligand hyaluronan is postulated to provide a homing signal for CD44-expressing MSCs [43].

Adult MSCs can be induced to develop phenotypic characteristics of fibroblasts, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes by in vitro exposure to growth factors and cytokines [55]. In one report, co-culture of human MSCs with primary human airway epithelial cells in vitro resulted in acquisition of phenotypic and functional epithelial characteristics by the MSCs [13]. This suggests that release of soluble mediators by lung epithelial cells and/or direct cell-cell contact between epithelial and mesenchymal cells can influence phenotypic conversion of MSCs to lung epithelial cells. However, specific factors directing conversion to lung epithelial phenotype have not been elucidated. Exposure of circulating fibrocytes to ligands upregulated in fibrotic lung injury including TGFβ-1 and endothelin-1 promote differentiation into a myofibroblast phenotype [27]. Little other additional information is available concerning the mechanisms, particularly cell signaling and regulation of gene expression by which adult marrow-derived cells may be induced to undergo phenotypic change acquiring characteristics of lung epithelial, vascular endothelial, or interstitial cells.

6. Endogenous Lung Stem Cells

Endogenous tissue stem cells are undifferentiated cells that been identified in nearly all tissues and contribute in varying degrees to tissue maintenance and repair. These endogenous stem cells are rare, self-renewing morphologically unspecialized cells that cycle infrequently and are usually localized to specialized niches within each tissue. These cells give rise to daughter cells known as transit amplifying cells that have higher rates of proliferation and give rise to the more specialized cells of the organ [56]. In lung, several populations of stem cells have been identified along the tracheobronchial tree [57–60] (Figure 3). In trachea and large airways, basal and non-ciliated secretory epithelial cells have been implicated. In more distal airways, neuro-endocrine and Clara cells have been identified as having stem and progenitor function. For example, Clara cells exhibit characteristics of transit-amplifying cells following injury to terminally differentiated cells. However, unlike transit-amplifying cells in tissues with higher rates of epithelial turnover, such as intestine, Clara cells exhibit a low proliferative frequency in the steady-state, are broadly distributed throughout the bronchiolar epithelium, and contribute to the specialized tissue activates through expression of differentiated characteristics. In the alveoli, type 2 alveoli are recognized as progenitors for type 1 alveolar epithelial cells. Interestingly, alveolar epithelium in CF patients contain primitive cuboidal cells that express primitive cell markers including thyroid transcription factor and cytokeratin 7 [61]. This suggests that endogenous progenitor cell pathways in CF lungs may be altered but this has not been extensively investigated.

Figure 3.

Endogenous regenerative microenvironments in the bronchiolar epithelium of the mouse. In situ hybridization for CCSP mRNA (white autoradiographic grains) was used to identify regions of regenerating epithelium following naphthalene-mediated progenitor cell depletion. Regenerative zones of neuroepithelial bodies were identified located at branch points in the airways (red ovals) and at the bronchoalveolar duct junction (green ovals). Figure courtesy of Susan Reynolds and Barry Stripp, University of Pittsburgh and reprinted with permission from Weiss et al Proc Am Thoracic Soc 2006;3:193 [7].

Evidence for the components of an airway and alveolar epithelial stem cell hierarchy derive from animal models in which selective ablation of epithelial cells is achieved through exposure to toxic chemicals or through cell type-specific expression of toxin genes in transgenic mice. Endogenous lung stem cells may also participate in development of lung carcinoma although the connection between tissue stem cells and cancer stem cells has not been established [62]. Future studies are needed to define the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating activity of endogenous lung stem cells and further characterization of the niches in which they reside. Endogenous stem cells may also be attractive candidates for targeting with gene transfer vectors that provide sustained expression.

Summary

The use of embryonic and adult stem cells for lung repair and regeneration after injury holds promise as a potential therapeutic approach for CF and other lung diseases. However, current studies are still in their infancy and there is much to be understood prior to realistically contemplating clinical strategies with these cells. Comparably, further understanding of endogenous cell populations in the lung will yield insights into lung development and into lung repair after injury and may also provide novel therapeutic strategies for a variety of lung diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Korbling M, Estrov Z. Adult stem cells for tissue repair - a new therapeutic concept? N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):570–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prockop DJ. Further proof of the plasticity of adult stem cells and their role in tissue repair. J Cell Biol. 2003;160(6):807–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzog EL, Chai L, Krause DS. Plasticity of marrow-derived stem cells. Blood. 2003;102(10):3483–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Cell fate determination from stem cells. Gene Therapy. 2002;9(10):606–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone- marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature. 2003;422:897–901. doi: 10.1038/nature01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camargo FD, Green R, Capetanaki Y, et al. Single hematopoietic stem cells generate skeletal muscle through myeloid intermediates. Nat Med. 2003;9:1520–7. doi: 10.1038/nm963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss DJ, Berberich MA, Borok Z, et al. National Heart Lung Blood Institute/Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Workshop Report Adult Stem Cells, Lung Biology, and Lung Disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3:193–207. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-013MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuringer IP, Randell SH. Lung stem cell update: promise and controversy. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease. 2006;65(1):47–51. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2006.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rippon HJ, Polak JM, Qin M, Bishop AE. Derivation of distal lung epithelial progenitors from murine embryonic stem cells using a novel three-step differentiation protocol. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1389–98. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samadikuchaksaraei A, Cohen S, Isaac K, Rippon HJ, Polak JM, Bielby RC, Bishop AE. Derivation of distal airway epithelium from human embryonic stem cells. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(4):867–75. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sueblinvong V, Loi R, Jaskolka JR, Poynter ME, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. IL-17 and SDF-1 Mediate Recruitment of Cord Blood Stem Cells to Lung Epithelium. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2006;29:A302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger MJ, Adams SD, Tigges BM, Sprague SL, Wang XJ, Collins DP, McKenna DH. Differentiation of umbilical cord blood-derived multilineage progenitor cells into respiratory epithelial cells. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(5):480–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600941549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang G, Bunnell BA, Painter RG, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma differentiate into airway epithelial cells: potential therapy for cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(1):186–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suratt BT, Cool CD, Serls AE, et al. Human pulmonary chimerism after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(3):318–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-145OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattsson J, Jansson M, Wernerson A, Hassan M. Lung epithelial cells and type II pneumocytes of donor origin after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78(1):154–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000132326.08628.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleeberger W, Versmold A, Rothamel T, et al. Increased chimerism of bronchial and alveolar epithelium in human lung allografts undergoing chronic injury. Am J Pathol. 2004;162(5):1487–94. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64281-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer H, Rampling D, Aurora P, et al. Transbronchial biopsies provide longitudinal evidence for epithelial chimerism in children following sex mismatched lung transplantation. Thorax. 2005;60(1):60–2. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trotman W, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Beatty BG, Weiss DJ. Dual Y chromosome painting and in situ cell-specific immunofluorescence staining in lung tissue: an improved method of identifying donor marrow cells in lung following bone marrow transplantation. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121(1):73–9. doi: 10.1007/s00418-003-0598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang JC, Summer R, Sun X, et al. Evidence that bone marrow cells do not contribute to the alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33(4):335–42. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0129OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotton DN, Fabian AJ, Mulligan RC. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33(4):328–34. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0175RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loi R, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. Limited restoration of defective cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult marrow derived cells. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2006. 2006;173:171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacPherson H, Keir PA, Edwards CJ, Webb S, Dorin JR. Following damage, the majority of bone marrow-derived airway cells express an epithelial marker. Respiratory Research. 2006;7:145. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruscia EM, Price JE, Cheng EC, et al. Assessment of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) activity in CFTR-null mice after bone marrow transplantation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(8):2965–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510758103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao YD, Courtman DW, Deng Y, Kugathasan L, Zhang Q, Stewart DJ. Rescue of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension using bone marrow-derived endothelial-like progenitor cells: efficacy of combined cell and eNOS gene therapy in established disease. Circ Res. 2005;96(4):442–50. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000157672.70560.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epperly MW, Guo H, Gretton JE, Greenberger JS. Bone marrow origin of myofibroblasts in irradiation pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29(2):213–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0069OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto N, Jin H, Liu T, et al. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(2):243–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI18847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, et al. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J Immunol. 2003;171(1):380–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomperts BN, Belperio JA, Burdick MD, Streiter RM. 2006. Circulating progenitor cells traffic via CXCR4/CXCL12 in response airway epithelial injury. J Immunol. 2006;176:1916–1927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mondrinos MJ, Koutzaki S, Jiwanmall E, Li M, Dechadarevian JP, Lelkes PI, Finck CM. Engineering three-dimensional pulmonary tissue constructs. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(4):717–28. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrade CF, Wong AP, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S, Liu M. Cell-based tissue engineering for lung regeneration. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular & Molecular Physiology. 2007;292(2):L510–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00175.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponticiello MS, Schinagl RM, Kadiyala S, Barry FP. Gelatin-based resorbable sponge as a carrier matrix for human mesenchymal stem cells in cartilage regeneration therapy. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2000 Nov;52(2):246–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<246::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong L, Peptan I, Clark P, Mao JJ. Ex vivo adipose tissue engineering by human marrow stromal cell seeded gelatin sponge. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;33(4):511–7. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-2510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunisaki SM, Freedman DA, Fauza DO. Fetal tracheal reconstruction with cartilaginous grafts engineered from mesenchymal amniocytes. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2006;41(4):675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spees JL, Olson SD, Ylostalo J, Lynch PJ, Smith J, Perry A, Peister A, Wang MY, Prockop DJ. Differentiation, cell fusion, and nuclear fusion during ex vivo repair of epithelium by human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris RG, Herzog EL, Bruscia EM, Grove JE, Van Arnam JS, Krause DS. Lack of a fusion requirement for development of bone marrow-derived epithelia. Science. 2004;305(5680):90–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1098925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denham M, Cole TJ, Mollard R. Embryonic stem cells form glandular structures and express surfactant protein C following culture with dissociated fetal respiratory tissue. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular & Molecular Physiology. 2006;290(6):L1210–5. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00427.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coraux C, Nawrocki-Raby B, Hinnrasky J, et al. Embryonic stem cells generate airway epithelial tissue. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 2005;32(2):87–92. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0079RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pickering SJ, Minger SL, Patel M, et al. Generation of a human embryonic stem cell line encoding the cystic fibrosis mutation deltaF508, using preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2005;10(3):390–7. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fauza Dario. Amniotic fluid and placental stem cells. Best Practice Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;18:877–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng B, Cao B, Li G, Huard J. Mouse adipose-derived stem cells undergo multilineage differentiation in vitro but primarily osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation in vivo. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(7):1891–901. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishizawa K, Kubo H, Yamada M, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to lung regeneration after elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema. FEBS Lett. 2004;556(1–3):249–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada M, Kubo H, Kobayashi S, et al. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells are important for lung repair after lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2004;172(2):1266–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz LA, Gambelli F, McBride C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell engraftment in lung is enhanced in response to bleomycin exposure and ameliorates its fibrotic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(14):8407–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432929100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rojas M, Xu J, Woods CR, Mora AL, Spears W, Roman J, Brigham KL. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in repair of the injured lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33(2):145–52. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beckett T, Loi R, Prenovitz R, Poynter M, Goncz KK, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. Acute lung injury with endotoxin or NO2 does not enhance development of airway epithelium from bone marrow. Mol Ther. 2005;12(4):680–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta N, Su X, Serikov V, Matthay MA. Intrapulmonary administration of mesenchymal stem cells reduces LPS induced acute lung injury and mortality. Proc Am Thoracic Soc. 2006;3:A25. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hattori K, Heissig B, Tashiro K, Honjo T, Tateno M, Shieh JH, Hackett NR, Quitoriano MS, Crystal RG, Rafii S, Moore MA. Plasma elevation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 induces mobilization of mature and immature hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. Blood. 2001;97(11):3354–60. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rafii S, Heissig B, Hattori K. Efficient mobilization and recruitment of marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic stem cells by adenoviral vectors expressing angiogenic factors. Gene Ther. 2002;9(10):631–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frenette PS, Subbarao S, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH, Wagner DD. Endothelial selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 promote hematopoietic progenitor homing to bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(24):14423–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi H, Tahara M, Worgall S, Rafii S, Crystal RG. Mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells to lung by intratracheal administration of an adenovirus encoding stromal cell-derived factor-1. Molecular Therapy. 2003;7:S112. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorman SC, Babirad I, Post J, Watson RM, Foley R, Jones GL, O’Byrne PM. Progenitor egress from the bone marrow after allergen challenge: Role of stromal cell-derived factor 1α and eotaxin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(3):438–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore BB, Kolodsick JE, Thannickal VJ, Cooke K, Moore TA, Hogaboam C, Wilke CA, Toews GB. CCR2-mediated recruitment of fibrocytes to the alveolar space after fibrotic injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(3):675–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62289-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frenette PS, Subbarao S, Mazo IB, von Andrian UH, Wagner DD. Endothelial selectins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 promote hematopoietic progenitor homing to bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(24):14423–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phinney D, Kopen G, Isaacson RL, Prockop D. Plastic Adherent Stromal Cells From the Bone Marrow of Commonly Used Strains of Inbred Mice: Variations in Yield, Growth, and Differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 1999;72:570–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rawlins EL, Hogan BLM. Epithelial stem cells of the lung: privileged few or opportunities for many? Development. 2006;133:2455–2465. doi: 10.1242/dev.02407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giangreco A, Reynolds SD, Stripp BR. Terminal bronchioles harbor a unique airway stem cell population that localizes to the bronchoalveolar duct junction. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:173–82. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoch KG, Lori A, Burns KA, et al. A subset of mouse tracheal epithelial basal cells generates large colonies in vitro. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular & Molecular Physiology. 2004;286(4):L631–42. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00112.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engelhardt JF, Schlossberg H, Yankaskas JR, Dudus L. Progenitor cells of the adult human airway involved in submucosal gland development. Development. 1995;121:2031–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zepeda ML, Chinoy MR, Wilson JM. Characterization of stem cells in human airway capable of reconstituting a fully differentiated bronchial epithelium. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1995;21:61–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02255823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hollande E, Cantet S, Ratovo G, Daste G, Bremont F, Fanjul M. Growth of putative progenitors of type II pneumocytes in culture of human cystic fibrosis alveoli. Biology of the Cell. 2004;96(6):429–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim CF, Jackson EL, Woolfenden AE, Lawrence S, Babar I, Vogel S, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Jacks T. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121(6):823–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]