SUMMARY

The goal of this review is to critically appraise the clinical evidence guiding our application of dental implant therapy relative to glycemic control for patients with diabetes.

Our initial searches of the literature identified 129 publications relevant to both dental implants and diabetes. These were reduced to 17 clinical studies for inclusion. Reported implant failure rates in these 17 reports ranged from 0 to 14.3% for patients with diabetes. Unfortunately, the majority of these reports lacked sufficient information relative to glycemic control to allow the application of the findings toward clinical care. However, clinical evidence is emerging from several investigations that diabetes and glycemic control are important considerations that may require modifications to therapeutic protocols, but may not be contraindications to implant therapy in diabetes patients. Also, a potentially important role for implant therapy to support oral function in diabetes dietary management remains to be determined.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder that is reaching epidemic proportions, recently projected as affecting over 350 million individuals worldwide. The number of affected individuals underlines the urgent need to understand the effects of diabetes and improve the care for patients with diabetes (Danaei et al. 2011).

Diabetes mellitus has long been considered a relative contraindication to dental implant therapy. Our understanding of diabetes mellitus as a relative contraindication, based on the patient’s level of glycemic control, has changed little since the 1988 NIH Consensus Conference on Dental Implants (National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference 1988, World Workshop in Periodontics 1996, Javed & Romanos 2009). As a result, well-controlled diabetic patients may be considered appropriate for implant therapy while diabetic patients lacking good glycemic control may be denied the benefits of implant therapy.

Given the importance of an evidence basis for care, this review is designed to critically examine the evidence available for the use of implant therapy for patients with diabetes based on glycemic control. Importantly, clinical studies directly examining the relationship between diabetes and implant survival, and the potential for glycemic control to serve as an appropriate discriminator for the application of care, are considered.

GLYCEMIC CONTROL

Glycemic control has long been the primary consideration for implant patients with diabetes. This appears appropriate given the correlations between glycemic control and microvascular and macrovascular complications (Cohen & Horton 2007). While there are multiple methods to assess glycemic levels, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is becoming the most frequently used and valuable diagnostic and therapeutic measure of blood glucose control.

The HgA1c value represents the percentage of non-enzymatically glycated A1c hemoglobin in red blood cells. This value is based on the average circulating time of a red blood cell – 60 - 90 days – and reflects the average blood glucose exposure over two to three months. Elevated HbA1c levels correlate directly with morbidity and mortality in diabetes (Boltri et al. 2005). Therefore, achieving low HbA1c levels serves as an important therapeutic target in the management of diabetes (Wysham 2010). Recent recommendations for strict glycemic control for persons with diabetes have targeted maximal HbA1c levels ranging from 6.5% up to 7.0% (Rodbard et al. 2009, Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, 2010).

MASTICATORY FUNCTION AND DIABETES

Periodontal disease frequently results in tooth loss, with the cumulative effects most significant in older patients (Albandar et al. 1999). It is these older patients who are also particularly susceptible to type 2 diabetes and its comorbidities. Thus, one of the more subtle complications of diabetes may be a decrease in a patient’s health and quality of life due to tooth loss and compromised function (McGrath & Bedi 2001). Importantly, compromises in masticatory function that lead to alterations in dietary behaviors for diabetic patients may be an essential consideration in the overall disease management for these patients, directly impacting glycemic control (Kawamura et al. 2001, Nuttall et al. 2003, Roumanas et al. 2003, Savoca et al. 2010). Therefore, oral health and functional tooth replacement must be considered in the overall dietary and nutritional management of patients with diabetes (Quandt et al. 2009). It may be those individuals with significant oral debilitation and difficulties managing glycemic levels who have the most to gain from improvements in oral function associated with implant therapy.

BONE METABOLISM AND DIABETES MELLITUS

Dental implant survival is initially dependent upon successful osseointegration following placement. Subsequently, as an implant is restored and placed into function, bone remodeling becomes critical to long-term implant survival in responding to the functional demands placed on the implant restoration and supporting bone. The critical dependence on bone metabolism for implant survival may be a vulnerability for patients with diabetes.

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes have been associated with osteopathic outcomes. Several recent meta-analyses of clinical studies have identified direct associations between type 2 diabetes and increased risk of fracture, however, they failed to find an association between HbA1c levels and fracture risk (Janghorbani et al. 2006, Vestergaard 2007, Asano et al. 2008). These results are also consistent with their finding no association between bone density and HbA1c (Janghorbani et al. 2006, Asano et al. 2008). Therefore, the importance of glycemic control as a factor for compromised bone metabolism has yet to be realized at a systemic level.

DIABETES AND IMPLANT INTEGRATION

As questions remain as to the effects of diabetes and glycemic control on bone metabolism, it is important for us to consider these effects for implant therapy as well. A thorough review of the literature for clinical investigations examining diabetes and dental implant survival identified 17 primary studies, many of which are frequently cited in support of diabetes as a relative contraindication to implant therapy. The majority of the studies identified in this review, 13 of 17 reports, were undertaken with the prevailing view that good glycemic control is critical to the successful use of implant therapy for patients with diabetes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies with partial information on glycemic control

| Reference | Study type | Follow- up time |

Patient Population |

# of patients |

# of implants |

Quantitative glycemic control |

# of patient experiencing failure (rate) |

# of implants failed (rate) |

Findings and conclusions of the study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies with limitations in assessment/reporting of glycemic control | Shernoff et al. 1994 | Prospective | 1y | T2D | 89 | 178 | NR | 11 (12.4%) |

13 (7.3%) | “Implants can be considered for T2D patients” |

| Kapur et al. 1998 | Prospective | 2y | T1D T2D |

52 | 104 | GHb= mean 9.1% |

0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | “…implants can be successfully used…in DM patients with even low to moderate levels of metabolic control.” |

|

| Balshi & Wolfinger 1999 | Retrospective | NR | NR | 34 | 227 | NR | 6 (17.6%) | 14 (6.2%) | “…high success rate is achievable when dental implants are placed in DM patients whose disease is under control.” |

|

| Morris et al. 2000 | Retrospective | 3y | ND T2D |

NR | 2632 ND 255 T2D |

NR | NR | ND: 180 (6.8%) T2D: 20 (7.8%) |

“…the use of endosseous dental implants for T2D patients involves a marginal risk to long-term implant survival.” |

|

| Fiorellini et al. 2000 | Retrospective | mean 4y | T1D T2D |

40 | 215 | NR | NR | 31 (14.3%) | “[no]…relationship between failure and… level of diabetic control…“ AND “…implants… in well-controlled DM patients…[have] reduced success and survival…” |

|

| Olson et al. 2000 | Prospective | 5y | T2D | 89 | 178 | FPG=154mg/dl HbAlc: normal or above |

14 (15.7%) |

16 (9.0%) | “…degree of diabetic control…did not make a significant difference in implant outcome.“ “…endosseous dental implants…for…T2D patients…predictable procedure.” |

|

| Farzad et al. 2002 | Retrospective | iy | T1D T2D |

25 | 136 | NR | 3 (12.0%) | 8 (5.9%) | “ Diabetics that undergo dental implant treatment do not encounter higher failure rate than the normal population if the patients’ plasma glucose level is normal or close to normal…” |

|

| van Steenberghe et al. 2002 | Prospective | NR | T1D T2D |

NR | ~30 | NR | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | “…controlled T1D and T2D…did not lead to an increased incidence in the early-failure group.” |

|

| Peled et al., 2003 | Prospective | 3y | T2D | 41 | 141 | FPG/NR | NR | 4 (2.8%) | “…dental implants can be used in DM patients if…proper patient selection and…diabetes is well controlled.” |

|

| Abdulwassie & Dhanrajani 2002 | Prospective | NR | NR | 25 | 113 | FPG≤126 mgl/dl |

NR | 5 (4.4%) | “Dental implants can be used successfully in patients who are diabetic provided that blood sugar levels are under control” |

|

| Moy et al. 2005 | Retrospective | ≤21 y | NR | 48 | NR | NR | 15 (31.8%) |

NR | “Significantly increased failure rates were seen in …diabetics.” | |

| Alsaadi et al. 2008a | Prospective | up to loading |

ND T2D |

283 | 682 ND 24T2D |

NR | NR | ND: 13 (1.9%) T2D: 1 (4.2%) |

“Certain factors, such as… Controlled T2D, …did not lead to an increased incidence in the early failures.” |

|

| Anner et al. 2010 | Retrospective | mean 30.8m |

NR | 426 ND 49 DM |

1449 ND 177 DM |

NR | ND: 54 (12.7%) DM: 4 (8.2%) |

ND: 72 (5.0%) DM: 2 (2.8%) |

“This study found no evidence of diminished clinical success or significant early healing complications associatedwith implant therapy in patients with controlled T2D.” |

|

| Cumulative Implant Failure Rate for all applicable studies | ND: 265(5.6%) DM: 114 (6.4%) |

|||||||||

All 13 of these studies looked to include only patients considered as having acceptable glycemic control in order to receive implant therapy. Nine of the 13 studies did not quantify glycemic levels, and the four investigations that did document glycemic levels suggested that not all enrolled patients were well-controlled. However, for these four studies, there was considerable variability in the evaluation or documentation of the patients’ glycemic levels, leaving the findings not clearly interpretable toward clinical care (Kapur et al. 1998; Olson et al. 2000; Abdulwassie & Dhanrajani 2002; Peled et al. 2003).

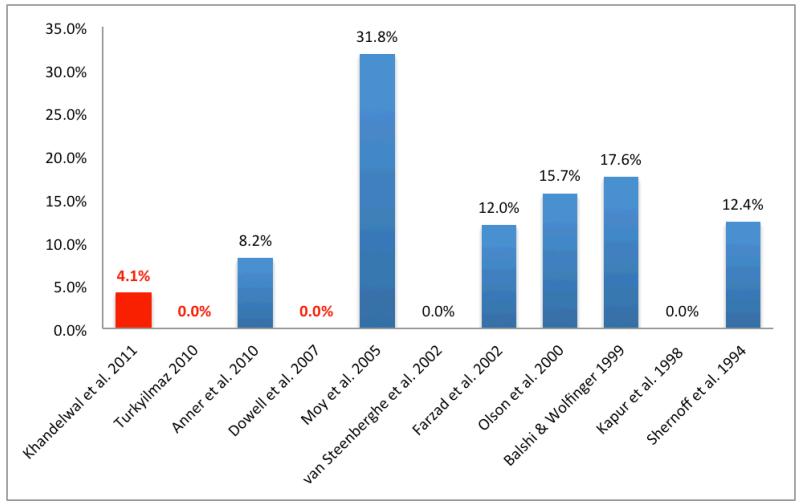

Evaluation of implant failure rates for these 13 studies demonstrated considerable variability in the rate of implant failure in patients with diabetes (0 to 14.3%; Fig. 1). Additionally, the rate at which diabetic patients receiving one or more implants experienced at least one failed implant was also highly variable (0 to 31.3%, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Implant failure rate (%) reported for studies on implant outcomes in patients with diabetes. Studies reporting HbA1c levels for patients highlighted in red

Fig. 2.

Patient failure rate (%) for studies on implant outcomes in patients with diabetes. Studies reporting HbA1c levels for patients highlighted in red

A search of the literature also identified four of the 17 studies in which patients lacking acceptable glycemic control were included and reported specifically defined assessments of glycemic control (Table 2). In contrast to the studies lacking this methodological detail, these four studies had implant failure rates ranging from 0 to 3.9%, and the rate of patients experiencing implant failure from 0 to 4.1% (Table 2). These four reports extend our understanding of the effects of diabetes by including patients with only moderate or poor glycemic control and warrant specific consideration (Dowell et al. 2007, Tawil et al. 2008, Turkyilmaz 2010, Khandelwal 2011).

Table 2.

Studies meeting glycemic control documentation criteria (including the report of the assessment method and the stratification of glycemic control from a qualitative and quantitative point of view)

| Reference | Study type | Follow-up time | Patient Population |

# of patients |

# of implants |

Qualitative glycemic control |

Quantitativ e glycemic control (HbA1c%) |

# of patients |

# of implants |

# of patient experienci ng failure (rate) |

# of implants failed (rate) |

Findings and conclusions of the study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dowell et al. 2007 | Prospective | 4m | ND T2D |

10 ND 25 T2D |

11 ND 39 T2D |

ND | <6 | 10 | 12 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

“ …no evidence of diminished clinical success or significant early healing complications associated with implant therapy based on the glycemic control levels of patients with T2D.” |

|

| Well | 6.0-8.0 | 10 | 17 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

||||||||

| Moderate | 8.1-10.0 | 12 | 17 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

||||||||

| Poor | >10.0 | 3 | 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) |

||||||||

| Tawil et al. 2008 | Prospective | mean 42.4m (1-12 y) |

ND T2D |

45 ND 45 T2D |

244 ND 255 T2D |

ND | NR | 45 | 244 | NR | 1 (0.4%) |

“ Well- to fairly well-controlled DM patients…had the same overall survival rates as controls…” 7#x201C;…6 of 7 failures occurred [within] first year…” Note: study did include immediate loading of implants. “HbAlc is the most important factor affecting implant complication rate.” |

|

| Well | <7.0 | 22 | 103 | NR | 1 (1.0%) |

||||||||

| Moderate | 7.0-9.0 | 22 | 141 | NR | 5 (3.5%) |

||||||||

| Poor | >9.0 | 1 | 11 | NR | 1 (9.1%) |

||||||||

| Moderate- Poor |

≥7.0 | 23 | 152 | NR | 6 (3.9%) |

||||||||

| All T2D | 45 | 255 | NR | 7 (2.9%) |

|||||||||

| Turkyilmaz 2010 | Prospective | 1y | T2D | 10 | 23 | Well | ≤8.0 | 6 | 15 | 0 (0.0%) |

0 (0%) |

“ …dental implant treatment can be offered to patients with well or moderately controlled T2D.” |

|

| Moderate | 8.1-10.0 | 4 | 8 | 0 (0.0%) |

0 (0%) |

||||||||

| Khandelwal 2011 | Prospective | 4m | T2D | 24 | 48 | Poor | 8.0-12.0 | 24 | 48 | 1 (4.1%) | 1 (2%) | “ …this study demonstrated clinically successful implant placement in poorly controlled diabetic patients.” |

|

| cumulative Implant Failure Rate for all applicable studies | ND:1(1.8%) DM:8(2.2%) |

||||||||||||

The first of these studies evaluated implant healing over a four-month evaluation period prior to implant restoration. Importantly, this landmark study did so for diabetic patients having an HbA1c of up to 12% at the time of surgery and with HbA1c levels extending as high as 13.8% over a four-month evaluation period (Dowell et al. 2007, Oates et al. 2009). The 25 diabetes patients ultimately enrolled in this study included 12 patients (17 implants) who would not be considered as well-controlled, having HbA1c levels between 8.1 to 10.0%, and three patients (four implants) with HbA1c levels over 10.0%. Also, as diabetes may affect bone metabolism differently following implant placement from that associated with long-term functional restoration, this study focused on understanding the effects of glycemic levels on the early healing events following implant placement prior to restoration.

This study failed to identify any implant failures over the four-month healing period. Interestingly, consistent with animal studies on the effects of hyperglycemia on bone metabolism, this study did identify significant compromises in implant integration in direct relation to HbA1c levels (Oates et al. 2009). Specifically, delays in implant integration were identified for patients with HbA1c levels over 8.0%, but not for patients below this level of glycemic control, consistent with increased risks for many diabetes comorbidities (Cohen & Horton 2007). This study’s findings show that the effects of hyperglycemia on implant integration, if clinically significant, were successfully accommodated with an extended healing period from two months to four months prior to functional loading as utilized in this study. It must be emphasized that this study did not evaluate implant failure over a longer time period following restoration.

In a second study, 45 diabetes patients having an initial HbA1c below 7.2% received 255 implants. They were followed over a period ranging from one to 12 years (Tawil et al. 2008). The HbA1c levels for these patients varied over the follow-up period, with frequency of HbA1c assessments not reported. HbA1c levels below 9% were identified for 44 patients, while one patient recorded an HbA1c level over 9%. This latter patient received 11 implants and had one failure, giving the study a seemingly high failure rate (9.1% implant failure rate) for this one patient. However, when this patient’s results are combined with the other 22 patients having only moderate glycemic control over the course of their evaluation period, the cumulative implant failure rate is 3.9%. As all these patients initiated implant therapy with an HbA1c <7.2% and the changes and duration of changes in HbA1c levels are unknown, the cumulative 2.9% failure rate for all diabetic patients remains most relevant.

This study is limited by the lack of clarity as to when the HbA1c levels were obtained for the patients during the follow-up period and when implant failures were identified. This study also failed to find a statistically significant difference in implant survival based on HbA1c levels, yet interestingly concluded that HbA1c is the most important factor affecting the implant complication rate. Presumably, this conclusion is based on the trend observed in the study data for the single patient receiving 11 implants, however patient numbers and limitations in HbA1c reporting as noted limit the value of this interpretation.

The third of these four studies was a recent prospective case series of 10 patients with diabetes that included four patients with HbA1c levels between 8.1% and 10.0%. This study evaluated implant survival after one year of restoration and reported no implant failures suggesting that short-term loading of the implants may not be detrimental to implant success in this patient population (Turkyilmaz 2010).

The most recent of these investigations reports the short-term healing (four months) for 48 implants placed in 24 poorly controlled diabetes patients. This study extends beyond previous studies by focusing on implant therapy specifically for those patients with poor glycemic control. The HbA1c levels ranged from 7.5 to 12.5% at study enrollment and had a mean level of 9.5% over the four months of the study. This study reported one implant failure during the four-month healing period for a 2% failure rate in this otherwise vulnerable population.

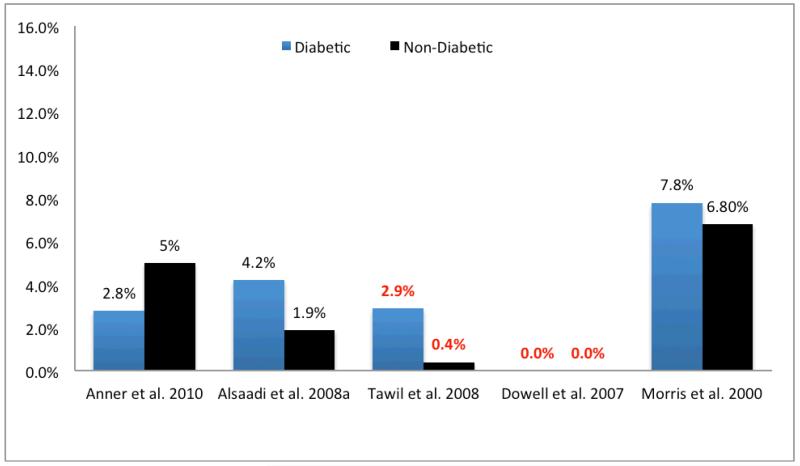

It is critical to our use of implant therapy in diabetic patients to recognize the limitations in information available for diabetes status and glycemic control in the interpretation of the results from many of these studies. This deficiency limits the application of their results toward the development of specific evidence-based guidelines to care for patients with diabetes. Additionally, in only five of these 17 studies was a comparative non-diabetic control population assessed (Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that the findings from these five studies also failed to demonstrate a significant difference in implant failure rates between diabetic (ranging from 0 to 7.8%) and non-diabetic patients (ranging from 0 to 6.8%).

Fig. 3.

Implant failure rate (%) reported for studies on implant outcomes treating both patients with diabetes and non-diabetic patients as controls. Studies reporting HbA1c levels for patients have rates highlighted in red

Taken together, it appears that several more recent studies of implant success with better-defined parameters of glycemic control support the use of dental implants for patients with diabetes mellitus with little increase in risk independent of glycemic status. It is important to note that while these studies were designed to examine the role for glycemic control in implant survival, these findings must be viewed as preliminary in that they include relatively small numbers of patients having elevated glycemic levels and offer only limited information on the longer term effects of diabetes on implant survival. It is also important to consider the potential for many other factors such as technologic advances in implant designs or specific therapeutic protocols to alter survival rates for implants in patients with diabetes. Cumulative failure rates from these studies (Tables 1 and 2) begin to address this concern by directly comparing findings with non-diabetic control groups within studies, and these findings suggest only subtle differences in failure rates between diabetic (2.2 to 6.4%) and non-diabetic (1.8 to5.6%) patients.

CONCLUSION

Oral health is an integral part of nutritional well-being and systemic health. Chronic diseases such as diabetes have oral sequelae that may lead to compromises in oral function. These compromises may importantly modulate dietary interventions critical to the overall management of diabetes (Touger-Decker & Mobley 2003). From a medical standpoint, there is no doubt that long-term good glycemic control is critical to minimizing diabetes-related comorbidities. However, good glycemic control may be dependent in part upon proper masticatory function.

With diabetes contributing to oral pathologies and tooth loss, tooth replacement utilizing implant therapy may be an important contributor to the patient’s overall well-being. Based on available literature, there are no clinical data supporting a significantly increased risk of implant failure for patients lacking good glycemic control. More recent studies with defined glycemic levels support the use of dental implant therapy for patients in the absence of good glycemic control. Therefore, with the potential benefit implant therapy has to offer, it may actually be in the diabetic patient’s best interest to consider implant therapy, even in the absence of proper glycemic control. While this represents a shift in attitude toward diabetic patient care, it is one that requires careful consideration of both the risks and benefits of care, as well as our current limitations in our understanding of these relationships.

References

((Layout: Bibliographie enthält kursive und fette Passagen; bitte so übernehmen))

- Abdulwassie H, Dhanrajani PJ. Diabetes mellitus and dental implants: A clinical study. Implant Dentistry. 2002;11:83–86. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200201000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988-1994. Journal of Periodontology. 1999;70:13–29. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaadi G, Quirynen M, Michiles K, Teughels W, Komarek A, van Steenberghe D. Impact of local and systemic factors on the incidence of failures up to abutment connection with modified surface oral implants. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2008a;35:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaadi G, Quirynen M, Komarek A, van Steenberghe D. Impact of local and systemic factors on the incidence of late oral implant loss. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2008b;19:670–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anner R, Grossmann Y, Anner Y, Levin L. Smoking, diabetes mellitus, periodontitis, and supportive periodontal treatment as factors associated with dental implant survival: a long-term retrospective evaluation of patients followed for up to 10 years. Implant Dentistry. 2010;19(1):57–64. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3181bb8f6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Fukui M, Hosoda H, Shiraishi E, Harusato I, Kadono M, Tanaka M, Hasegawa G, Yoshikawa T, Nakamura N. Bone stiffness in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57:1691–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshi TJ, Wolfinger GJ. Dental implants in the diabetic patient: A retrospective study. Implant Dentistry. 1999;8:355–359. doi: 10.1097/00008505-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boltri JM, Okosun IS, Davis-Smith M, Vogel RL. Hemoglobin a1c levels in diagnosed and undiagnosed black, hispanic, and white persons with diabetes: Results from nhanes 1999-2000. Ethnicity and Disease. 2005;15:562–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Horton ES. Progress in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: New pharmacologic approaches to improve glycemic control. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2007;23:905–917. doi: 10.1185/030079907x182068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, Lin JK, Farzadfar F, Khang YH, Stevens GA, Rao M, Ali MK, Riley LM, Robinson CA, Ezzati M, Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Blood Glucose) National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. The Lancet. 2011;378(9785):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell S, Oates TW, Robinson M. Implant success in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus with varying glycemic control: A pilot study. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2007;138:355–361. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0168. quiz 397-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzad P, Andersson L, Nyberg J. Dental implant treatment in diabetic patients. Implant Dentistry. 2002;11:262–267. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorellini JP, Chen PK, Nevins M, Nevins ML. A retrospective study of dental implants in diabetic patients. International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry. 2000;20:366–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janghorbani M, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Hu F. Prospective study of diabetes and risk of hip fracture: The nurses’ health study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1573–1578. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed F, Romanos GE. Impact of diabetes mellitus and glycemic control on the osseointegration of dental implants: A systematic literature review. Journal of Periodontology. 2009;80:1719–1730. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur KK, Garrett NR, Hamada MO, Roumanas ED, Freymiller E, Han T, Diener RM, Levin S, Ida R. A randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of mandibular implant-supported overdentures and conventional dentures in diabetic patients. Part i: Methodology and clinical outcomes. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 1998;79:555–569. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M, Tsurumoto A, Fukuda S, Sasahara H. Health behaviors and their relation to metabolic control and periodontal status in type 2 diabetic patients: A model tested using a linear structural relations program. Journal of Periodontology. 2001;72:1246–1253. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal N, Oates TW, Vargas A, Alexander PP, Schoolfield JD, Alex McMahan C. Conventional SLA and chemically modified SLA implants in patients with poorly controlled type 2 Diabetes mellitus - a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Oral Implants Research Dec 6. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02369.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath C, Bedi R. Can dentures improve the quality of life of those who have experienced considerable tooth loss? Journal of Dentistry. 2001;29:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris HF, Ochi S, Winkler S. Implant survival in patients with type 2 diabetes: Placement to 36 months. Annals of Periodontology. 2000;5:157–165. doi: 10.1902/annals.2000.5.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy PK, Medina D, Shetty V, Aghaloo TL. Dental implant failure rates and associated risk factors. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants. 2005;20:569–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement on dental implants June 13-15, 1988. Journal of Dental Education. 1988;52:824–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall FQ, Gannon MC, Saeed A, Jordan K, Hoover H. The metabolic response of subjects with type 2 diabetes to a high-protein, weight-maintenance diet. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;88:3577–3583. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates TW, Dowell S, Robinson M, McMahan CA. Glycemic control and implant stabilization in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Dental Research. 2009;88:367–371. doi: 10.1177/0022034509334203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JW, Shernoff AF, Tarlow JL, Colwell JA, Scheetz JP, Bingham SF. Dental endosseous implant assessments in a type 2 diabetic population: a prospective study. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2000;15(6):811–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled M, Ardekian L, Tagger-Green N, Gutmacher Z, Machtei EE. Dental implants in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A clinical study. Implant Dentistry. 2003;12:116–122. doi: 10.1097/01.id.0000058307.79029.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Chen H, Bell RA, Anderson AM, Savoca MR, Kohrman T, Gilbert GH, Arcury TA. Disparities in oral health status between older adults in a multiethnic rural community: The rural nutrition and oral health study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:1369–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, Einhorn D, Garber AJ, Grunberger G, Handelsman Y, Horton ES, Lebovitz H, Levy P, Moghissi ES, Schwartz SS. Statement by an american association of clinical endocrinologists/american college of endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: An algorithm for glycemic control. Endocrine Practice. 2009;15:540–559. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumanas ED, Garrett NR, Hamada MO, Kapur KK. Comparisons of chewing difficulty of consumed foods with mandibular conventional dentures and implant-supported overdentures in diabetic denture wearers. International Journal of Prosthodontics. 2003;16:609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoca MR, Arcury TA, Leng X, Chen H, Bell RA, Anderson AM, Kohrman T, Frazier RJ, Gilbert GH, Quandt SA. Severe tooth loss in older adults as a key indicator of compromised dietary quality. Public Health Nutrition. 2010;13:466–474. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009991236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shernoff AF, Colwell JA, Bingham SF. Implants for type ii diabetic patients: Interim report. VA implants in diabetes study group. Implant Dentistry. 1994;3:183–185. doi: 10.1097/00008505-199409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standards of medical care in diabetes--2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Supplement 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawil G, Younan R, Azar P, Sleilati G. Conventional and advanced implant treatment in the type ii diabetic patient: Surgical protocol and long-term clinical results. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Implants. 2008;23:744–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touger-Decker R, Mobley CC. Position of the american dietetic association: Oral health and nutrition. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:615–625. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkyilmaz I. One-year clinical outcome of dental implants placed in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A case series. Implant Dentistry. 2010;19:323–329. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e3181e40366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steenberghe D, Jacobs R, Desnyder M, Maffei G, Quirynen M. The relative impact of local and endogenous patient-related factors on implant failure up to the abutment stage. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2002;13:617–622. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes--a meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International. 2007;18:427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Workshop in Periodontics: Consensus report. Implant therapy II. Annals of Periodontology. 1996;1:816–820. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysham CH. New perspectives in type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular risk, and treatment goals. Postgraduate Medicine. 2010;122:52–60. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.05.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]