Abstract

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) assembles into two distinct multi-protein complexes called mTORC1 and mTORC2. While mTORC1 controls the signaling pathways important for cell growth, the physiological function of mTORC2 is only partially known. Here we comment on recent work on gene-targeted mice lacking mTORC2 in the cerebellum or the hippocampus that provided strong evidence that mTORC2 plays an important role in neuron morphology and synapse function. We discuss that this phenotype might be based on the perturbed regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and the lack of activation of several PKC isoforms. The fact that PKC isoforms and their targets have been implicated in neurological disease including spinocerebellar ataxia and that they have been shown to affect learning and memory, suggests that aberration of mTORC2 signaling might be involved in diseases of the brain.

Keywords: rictor, PKC, GAP-43, MARCKS, Adducin, Tiam1, Rac1, Purkinje cell, synaptic plasticity, dendrite

Introduction

mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that functions within two distinct protein complexes that are referred to as mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2). Differences in protein composition assign these two complexes specific functions. There are shared components, such as mTOR itself, mLST8, DEPTOR and the Tti1/Tel2 complex, but also some that are complex-specific. For mTORC1 this is raptor and PRAS40 and for mTORC2 rictor, mSin1 and Protor1/2.1 The best described function of mTOR is its role in cell growth, metabolism and aging, functions that all can be inhibited by the name-giving drug rapamycin, a macrolide isolated from a soil sample of Easter Island. Rapamycin and its derivatives, called rapalogs, are FDA approved as immunosuppressants after allograft transplantation, as anti-restenosis drugs in stents and for the treatment of some cancers.2 Current evidence suggests that the rapalogs act mainly via inhibiting mTORC1. In metazoans, mTORC1 is activated by growth factor signaling and, like in protozoans, by nutrients and the energy status of a cell. The main targets of mTORC1 are S6K and 4E-BP, which both control protein synthesis. Another important function of mTORC1 is the control of autophagy, a process that is essential to clean cells from unfolded proteins, non-functional organelles and to overcome the lack of nutrients during starvation.3 In summary, mTORC1 appears to be the main hub that controls cell growth and metabolism, which also explains its involvement in cancer. Recent evidence suggests a role of mTORC1 in diseases of the central nervous system, such as Alzheimer disease, autism spectrum disorders or epilepsy.4-7

In contrast to mTORC1, the role of mTORC2 has been studied much less and thus its function is not well defined. Rapamycin does not inhibit mTORC2 acutely although long-term treatment affects mTORC2 function.8 Activation of mTORC2 involves its PI3K-dependent association with ribosomes.9 Compared with mTORC1, the number of downstream targets of mTORC2 is much lower but includes several members of the AGC kinase family, among them Akt, PKC and SGK1. Some of these effectors, in particular Akt, are involved in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis, suggesting that mTORC2 might also contribute to cancerogenesis.10 Evidence obtained in yeast and in cultured mammalian cells in addition indicates a function of mTORC2 in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.11-13 However, major changes in cell shape and the cytoskeleton were not observed in tissue-specific deletion of rictor in skeletal muscle, adipocytes, liver or kidney.14-17 Only the recent deletion of rictor in the central nervous system revealed a role of mTORC2 for the shape of neurons18 and for synaptic plasticity, an adaptive response of synapses to changes in activity.19 Both of these functions involve the rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. In this commentary, we will briefly summarize those data and then discuss our view of how mTORC2 might regulate actin dynamics to shape neurons during development and of how this activity may contribute to synaptic plasticity in the adult.

mTORC2 Regulates Actin Cytoskeletal Rearrangements in Vivo

In recent work, we conditionally deleted rictor in the developing and the adult central nervous system by using mice that express Cre under the control of the nestin or the Purkinje cell-specific L7/Pcp-2 promoter. The two major findings of this work were that the brain was smaller and that the morphology of neurons was strongly affected.18 The microcephaly was a consequence of a reduction in neuron size but not number, which in turn resulted in an increased cell density. Interestingly, despite lower levels of phosphorylation of the mTORC2 target Akt, the microcephaly was not accompanied by alterations in any of the downstream targets of Akt; in particular, no changes in the mTORC1 targets S6K and 4E-BP were seen. Thus, mTORC2 appears to affect neuron size independently of mTORC1.

Changes in neuronal morphology encompassed the number, the length and the thickness of the neurites. Most notably, Purkinje cells of the cerebellum, which are characterized by expressing only one primary dendrite, contained up to six such primary dendrites. The changes in dendrite number were a cell-autonomous effect of rictor depletion as multiple primary dendrites were also observed when rictor was depleted selectively in Purkinje cells. The particularly strong changes in the morphology of the Purkinje cells were accompanied by an ataxia-like motor phenotype, consistent with the view that Purkinje cells, which provide the sole output of the cerebellum, are important for motor coordination.20

The molecular mechanisms involved in the neuronal phenotype observed in the rictor depleted brain were analyzed biochemically. Of all the bona fide targets of mTORC2, the most pronounced changes were observed in the PKC family of proteins. In rictor-deficient brain lysates, the phosphorylation and protein level of all classical PKCs (i.e., PKCα, -β and -γ) and the novel PKC isozyme, PKCε, were strongly reduced. In addition, phosphorylation of the PKC substrates GAP-43 and MARCKS, which are known to be important for the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton was diminished. Such a pronounced effect of mTORC2 ablation on the PKC pathway has so far not been reported in any other tissue. Interestingly, another group also reported on changes in the actin cytoskeleton of neurons in mice where rictor was conditionally deleted in the hippocampus.19 Those authors did not investigate PKC signaling but provided evidence that rictor depletion affected the Tiam1-Rac1-PAK-cofilin pathway. In summary, both studies provided first in vivo evidence that depletion of rictor specifically affects the actin cytoskeleton in neurons. This is in stark contrast to studies in other organs where little or no cytoskeletal disturbances have been described.

PKC Signaling and Its Downstream Substrates

Among the best-studied PKC substrates in the brain are GAP-43, MARCKS, fascin and adducins.21 GAP-43 and MARCKS have been proposed to share some function because both are highly hydrophilic and associate with plasma membranes via palmityolation and myristoylation, respectively, and are therefore frequently summed up as GAP-43-like proteins. In their dephosphorylated form, GAP-43 and MARCKS bind to PI(4,5)P2 and are associated with lipid raft-like structures of the plasma membrane.22 Phosphorylation of GAP-43 or MARCKS by classical or novel PKC isoforms results in their detachment from the plasma membrane. As a consequence, the levels of PI(4,5)P2 are decreased.22,23 Thus, the phosphorylation state of GAP-43 and MARCKS may directly affect the levels of PI(4,5)P2 in neurons and changes in PI(4,5)P2 have been implicated in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.24 Adducins are a family of three related genes, which encode for either α-, β- or γ-adducin. All of them possess an N-terminal head domain, a neck domain, and a C-terminal tail domain that includes a conserved 22 amino acid MARCKS-related domain, which is necessary for actin binding. Adducins form tetramers composed of either α/β- or α/β-heterodimers and cap the fast growing end of the actin filaments (F-actin) to recruit spectrin to those actin filaments. Phosphorylation of adducin by PKC within the C-terminal MARCKS-related domain reduces F-actin-capping and thereby promotes free-barbed ends that are prone to polymerization/depolymerization.25 Thus, adducins affect actin cytoskeleton dynamics and this activity is regulated by PKC.

Purkinje Cell Development and the Role of PKC Signaling

Purkinje cell development in rodents largely occurs between P0 and P21 and can roughly be split into three phases.26 At P0, Purkinje cells have small somata with multiple dendrites that are organized in a multipolar manner. In a first growth phase (P0 to ~P9), the somata of the Purkinje cells are enlarged and all but one primary dendrite are eliminated. This first phase is followed by the stage of rapid growth of the dendritic tree and a third phase of rather slow dendritic growth. Excessive neurite outgrowth or improper dendrite retraction during the first developmental stage may result in Purkinje cells with multiple primary dendrites.

As mentioned above, rictor-deficient Purkinje cells have too many primary dendrites. As PKC isoforms are strongly de-regulated in rictor knockout brains, the question arises whether these morphological changes might be based on alterations in PKC signaling. Indeed, there is evidence that PKC activity affects Purkinje cell development and function. For example, mutations in the gene coding for PKCγ, whose expression is strongly reduced in rictor-deficient brain, cause spinocerebellar ataxia 14 (SCA14).27 Although the exact molecular mechanisms involved in the ontogeny of SCA14 are not well understood, experiments in organotypic slice cultures of the cerebellum indicate that PKC is important for dendrite morphology of Purkinje cells.28-30 Purkinje cells also express high levels of mRNA encoding the PKC substrate MARCKS both during development and in the adult. In contrast, transcripts for GAP-43 are low in Purkinje cells at both stages,31 suggesting that GAP-43 is unlikely to be the main effector responsible for the changes observed in the cerebellum of the rictor-deficient brains. The PKC substrate fascin is highly expressed in the developing brain but cannot be detected anymore in adult Purkinje cells.32,33 In the adult brain, fascin seems rather to be expressed in non-neuronal cells and there is evidence that its expression correlates with morphology, invasiveness and motility of glioma cells.34 Finally, expression of α- and β-adducin is widespread in the brain while expression of γ-adducin is highest in the hippocampus and in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum.35,36 Interestingly, phosphorylation of adducin is also significantly diminished in the brain of rictor-deficient mice (Angliker and Rüegg, unpublished observation). Thus, the expression pattern of the PKC substrates in the cerebellum suggests that rictor, by controlling PKC phosphorylation and protein levels, may act in Purkinje cells through MARCKS and adducins but not via GAP-43 or fascin.

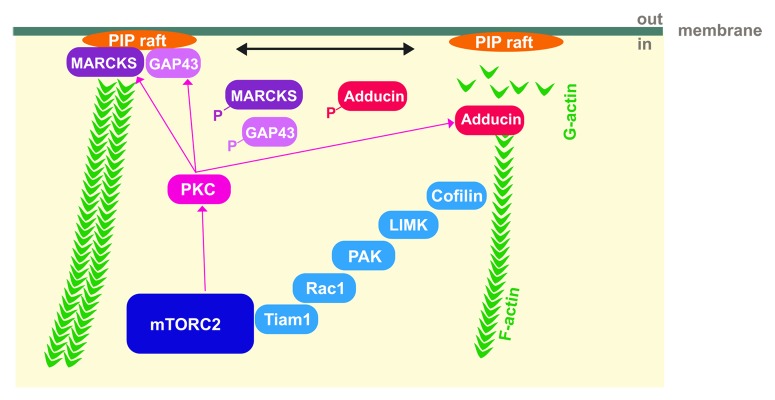

The change in the phosphorylation state of MARCKS and adducin in rictor knockout mice will shift the equilibrium between membrane/actin-bound and the cytosolic form of MARCKS and adducin toward membrane and the actin-bound form, respectively (Fig. 1). A shift in the relative amount of phosphorylated MARCKS has been implicated in dendrite morphology. For example, hyperactivity of PKC and thus hyperphosphorylation of MARCKS has been shown to contribute to the strongly reduced dendritic arborization observed upon forebrain-specific deletion of the gene cluster encoding the γ-protocadherins.37 Reduction of dendritic arborization by knockdown of MARCKS or overexpression of a “dominant-negative” (e.g., phosphomimetic) form of MARCKS was also reported in cultured hippocampal neurons.38 These results argue that the loss of phosphorylation of MARCKS in rictor-depleted neurons would result in exuberant dendritic branching. Indeed, rictor-knockout Purkinje cells show an increased number of primary dendrites.18

Figure 1. Model for the regulation of actin cytoskeletal dynamics by mTORC2. Activation of PKC by mTORC2 results in a phosphorylation of GAP-43-like proteins, MARCKS and GAP-43, which dissociate form PI(4,5)P2 rafts and make PI(4,5)P2 accessible for other actin cytoskeletal regulating proteins or hydrolysis. In parallel, PKC causes free-barbed actin filament ends by phosphorylating adducin which promotes actin dynamics. Association of mTORC2 with Tiam1 and the regulation of its downstream targets may also contribute to actin filament stabilization. In this model, mTORC2 affects depolymerization and polymerization of actin at different sites by controlling PKC- and Tiam1-signaling.

The Role of PKC and Its Downstream Substrates in Synaptic Plasticity

Changes in neuronal activity are known to affect neural circuits and current evidence suggests that such changes are the basis of learning and memory. On the cellular level, it is well established that neuronal activity can cause the weakening or strengthening of existing synapses and trigger the formation or elimination of synapses. Depending on the frequency of presynaptic neuronal activity (i.e., release of neurotransmitter) and the synchrony with the postsynaptic elements, synapses are strengthened (long-term potentiation; LTP) or weakened (long-term depression; LTD).

For example, the parallel fiber synapses of a Purkinje cell become depressed when stimulated in conjunction with a postsynaptic depolarization of the Purkinje cell via the innervating climbing fiber. PKC isoforms have been shown to be essential for this form of cerebellar LTD. This has been demonstrated using pharmacological inhibitors or activators of PKC and also by Purkinje cell-specific expression of a peptidic PKC inhibitor.39,40 Surprisingly, a knockout of PKCγ, the major PKC isoform in Purkinje cells, does not affect cerebellar LTD41 but more recent evidence indicates that PKCα is the essential isoform for this kind of synaptic plasticity.42 Although Purkinje cells of PKCγ knockout mice reveal normal cerebellar LTD, they fail to reduce the number of climbing fibers to a single one during their development, which results in adult Purkinje cells innervated by multiple climbing fibers.43 Interestingly, climbing fiber synapse elimination is also compromised in mice in which rictor is specifically depleted in Purkinje cells (Angliker and Rüegg, unpublished observation). Thus, this provides additional evidence that the neuronal phenotype observed in rictor-deficient neurons might be based on changes in PKC signaling.

Probably the best characterized form of LTP is generated between neurons of CA3 and CA1 region of the hippocampus upon high frequency stimulation of the Schaffer collaterals. The use of PKC inhibitors and activators has provided solid evidence for the notion that PKC isoforms also contribute to synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus.44 Furthermore, there is evidence that PKC activation and expression is lost in transgenic mouse models that reiterate the memory loss observed in Alzheimer disease. Importantly, treatment of those mice with the PKC activator bryostatin-1 or DCP-LA prevents the loss of memory.45 In line with this finding, the same activators have been reported to promote LTP in hippocampal slices.46

In the hippocampus, one can distinguish an early phase-LTP (E-LTP), which is based on changing the conductance or number of ion channels in the postsynaptic membrane and a late form, called L-LTP, which requires new protein synthesis and involves structural changes of the synapses. Recent work by Huang and colleagues (2013) provided strong evidence that rictor is required for L-LTP. The paper very nicely shows that rictor regulates actin polymerization, which is well known to affect synaptic plasticity, and that the defect in L-LTP results in a learning deficit in the mutant mice. Importantly, both the deficit in L-LTP and the impairment in learning are rescued by the application of jasplakinolide, which directly promotes actin polymerization.19 While Huang and colleagues provide evidence that the phenotype might be based on the rictor function to affect phosphorylation of Akt and on its regulatory function on the Tiam1-Rac1 pathway, changes in PKC signaling might also contribute to the phenotype as outlined below.

In particular, the PKC downstream target β-adducin has been implicated in synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus as mice deficient for β-adducin show an impairment in CA3-CA1 LTP and LTD and deficits in spatial learning.47,48 Noteworthy, these knockout mice also show motor coordination deficits, which manifest in a decreased latency to fall off a rotating rod. When β-adducin knockout mice are exposed to an enriched environment, a stimulus that increases synapse formation and turnover, synapses still disassemble but fail to be reformed, which is paralleled by deficits in augmented hippocampus-dependent learning. Enhanced enrichment upregulates phosphorylation of β-adducin in a PKC-sensitive manner and PKC activity was found to be crucial for the disassembly of synapses upon enrichement, a process that is essential for augmented learning as well. Altogether, these findings demonstrate the importance of β-adducin and its PKC-mediated phosphorylation for hippocampal synaptic plasticity that underlies augmented learning.49 It should be noted that adducins are expressed both pre- and postsynaptically suggesting that perturbation of their function may affect both parts of the synapse. A presynaptic effect seems indeed to dominate over the postsynaptic effect in Drosophila, where it has been shown that the presynaptic expression of adducin (also called Hts) is sufficient to rescue the morphological changes at the neuromuscular junction of adducin-deficient flies.50 These studies are very strong evidence that adducins can affect actin dynamics and thereby influence synaptic plasticity. Thus, many of the phenotypes observed in mice that are deficient for rictor in neurons might be based on the changes in PKC signaling.

Conclusion

We propose that actin cytoskeleton regulation by mTORC2 occurs in a canonical manner, for example via PKC activation and their downstream targets like GAP-43, MARCKS or adducin. To satisfy the demands of the brain for functional and anatomical plasticity, it might express not only a subset of mTORC2 downstream targets that regulate actin dynamics but a rather large panel of them, thereby possibly generating some redundancy, which in turn also might guarantee stability. The last notion is also reflected in the suggestion that GAP-43-like proteins possibly compensate the knockout of each other. However, usage of different mTORC2 downstream targets likely also varies among different brain regions and during brain development, dependent on their temporal and spatial expression profiles. In general, ablation of rictor in the brain seems to cause dysregulation of several proteins involved in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and hence result in strong morphological changes. Additionally, the brain is an optimal organ to detect morphological alterations on the cellular level since neurons show elaborate growth and branching of neurites.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Judith Reinhard for valuable input and careful reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Sinergia grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation and by funds from the Cantons of Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CA1

Cornu Ammonis area 1

- CA3

Cornu Ammonis area 3

- DEPTOR

DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GAP-43

growth-associated protein-43

- Hts

Hu-li tai shao

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LTD

long-term depression

- E-LTP

early phase-LTP

- L-LTP

late phase-LTP

- mLST8

mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8

- mSin1

stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

mTOR complex 1

- mTORC2

mTOR complex 1

- MARCKS

myristoylated, alanine-rich C kinase substrate

- raptor

regulatory-associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin

- rictor

rapamycin-insensitive companion of mammalian target of rapamycin

- S6K

S6 kinase

- P

postnatal day

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PI(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-diphosphate

- PRAS40

proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa

- Protor1/2

protein observed with rictor 1 and 2

- SCA14

spinocerebellar ataxia 14

- SGK1

serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1

- Tiam1

T-cell-lymphoma invasion and metastasis-1 protein

- 4E-BP

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein

References

- 1.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin D, Colombi M, Moroni C, Hall MN. Rapamycin passes the torch: a new generation of mTOR inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:868–80. doi: 10.1038/nrd3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1845–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehninger D, Silva AJ. Rapamycin for treating Tuberous sclerosis and Autism spectrum disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santini E, Klann E. Dysregulated mTORC1-Dependent Translational Control: From Brain Disorders to Psychoactive Drugs. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:76. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai PT, Hull C, Chu Y, Greene-Colozzi E, Sadowski AR, Leech JM, Steinberg J, Crawley JN, Regehr WG, Sahin M. Autistic-like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature. 2012;488:647–51. doi: 10.1038/nature11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateup HS, Johnson CA, Denefrio CL, Saulnier JL, Kornacker K, Sabatini BL. Excitatory/inhibitory synaptic imbalance leads to hippocampal hyperexcitability in mouse models of tuberous sclerosis. Neuron. 2013;78:510–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zinzalla V, Stracka D, Oppliger W, Hall MN. Activation of mTORC2 by association with the ribosome. Cell. 2011;144:757–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Saitoh M, Kinkel S, Crosby K, Sheen JH, Mullholland DJ, Magnuson MA, Wu H, Sabatini DM. mTOR complex 2 is required for the development of prostate cancer induced by Pten loss in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:148–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Rüegg MA, Hall A, Hall MN. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1122–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–68. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentzinger CF, Romanino K, Cloëtta D, Lin S, Mascarenhas JB, Oliveri F, Xia J, Casanova E, Costa CF, Brink M, et al. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy. Cell Metab. 2008;8:411–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cybulski N, Polak P, Auwerx J, Rüegg MA, Hall MN. mTOR complex 2 in adipose tissue negatively controls whole-body growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9902–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811321106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gödel M, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Liu S, Zschiedrich S, Lu S, Debreczeni-Mór A, Lindenmeyer MT, Rastaldi MP, Hartleben G, et al. Role of mTOR in podocyte function and diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2197–209. doi: 10.1172/JCI44774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagiwara A, Cornu M, Cybulski N, Polak P, Betz C, Trapani F, Terracciano L, Heim MH, Rüegg MA, Hall MN. Hepatic mTORC2 activates glycolysis and lipogenesis through Akt, glucokinase, and SREBP1c. Cell Metab. 2012;15:725–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomanetz V, Angliker N, Cloëtta D, Lustenberger RM, Schweighauser M, Oliveri F, Suzuki N, Rüegg MA. Ablation of the mTORC2 component rictor in brain or Purkinje cells affects size and neuron morphology. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:293–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang W, Zhu PJ, Zhang S, Zhou H, Stoica L, Galiano M, Krnjević K, Roman G, Costa-Mattioli M. mTORC2 controls actin polymerization required for consolidation of long-term memory. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:441–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seidel K, Siswanto S, Brunt ER, den Dunnen W, Korf HW, Rüb U. Brain pathology of spinocerebellar ataxias. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson C. Protein kinase C and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Cell Signal. 2006;18:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laux T, Fukami K, Thelen M, Golub T, Frey D, Caroni P. GAP43, MARCKS, and CAP23 modulate PI(4,5)P(2) at plasmalemmal rafts, and regulate cell cortex actin dynamics through a common mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1455–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caroni P. New EMBO members’ review: actin cytoskeleton regulation through modulation of PI(4,5)P(2) rafts. EMBO J. 2001;20:4332–6. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janmey PA, Lindberg U. Cytoskeletal regulation: rich in lipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:658–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuoka Y, Li X, Bennett V. Adducin: structure, function and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:884–95. doi: 10.1007/PL00000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKay BE, Turner RW. Physiological and morphological development of the rat cerebellar Purkinje cell. J Physiol. 2005;567:829–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen DH, Brkanac Z, Verlinde CL, Tan XJ, Bylenok L, Nochlin D, Matsushita M, Lipe H, Wolff J, Fernandez M, et al. Missense mutations in the regulatory domain of PKC gamma: a new mechanism for dominant nonepisodic cerebellar ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:839–49. doi: 10.1086/373883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metzger F. Molecular and cellular control of dendrite maturation during brain development. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2010;3:1–11. doi: 10.2174/1874467211003010001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gundlfinger A, Kapfhammer JP, Kruse F, Leitges M, Metzger F. Different regulation of Purkinje cell dendritic development in cerebellar slice cultures by protein kinase Calpha and -beta. J Neurobiol. 2003;57:95–109. doi: 10.1002/neu.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrenk K, Kapfhammer JP, Metzger F. Altered dendritic development of cerebellar Purkinje cells in slice cultures from protein kinase Cgamma-deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2002;110:675–89. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higo N, Oishi T, Yamashita A, Matsuda K, Hayashi M. Cell type- and region-specific expression of protein kinase C-substrate mRNAs in the cerebellum of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:135–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.10850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Arcangelis A, Georges-Labouesse E, Adams JC. Expression of fascin-1, the gene encoding the actin-bundling protein fascin-1, during mouse embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:637–43. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang FR, Tao LH, Shen ZY, Lv Z, Xu LY, Li EM. Fascin expression in human embryonic, fetal, and normal adult tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:193–9. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7353.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang JH, Smith CA, Salhia B, Rutka JT. The role of fascin in the migration and invasiveness of malignant glioma cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:149–59. doi: 10.1593/neo.07909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidel B, Zuschratter W, Wex H, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED. Spatial and sub-cellular localization of the membrane cytoskeleton-associated protein alpha-adducin in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;700:13–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00962-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, Boe AF, Boguski MS, Brockway KS, Byrnes EJ, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–76. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrett AM, Schreiner D, Lobas MA, Weiner JA. γ-protocadherins control cortical dendrite arborization by regulating the activity of a FAK/PKC/MARCKS signaling pathway. Neuron. 2012;74:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Chen G, Zhou B, Duan S. Actin filament assembly by myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-diphosphate signaling is critical for dendrite branching. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4804–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C, Bian F, Koekkoek SK, van Alphen AM, Linden DJ, Oberdick J. Expression of a protein kinase C inhibitor in Purkinje cells blocks cerebellar LTD and adaptation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Neuron. 1998;20:495–508. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saito N, Shirai Y. Protein kinase C gamma (PKC gamma): function of neuron specific isotype. J Biochem. 2002;132:683–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C, Kano M, Abeliovich A, Chen L, Bao S, Kim JJ, Hashimoto K, Thompson RF, Tonegawa S. Impaired motor coordination correlates with persistent multiple climbing fiber innervation in PKC gamma mutant mice. Cell. 1995;83:1233–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leitges M, Kovac J, Plomann M, Linden DJ. A unique PDZ ligand in PKCalpha confers induction of cerebellar long-term synaptic depression. Neuron. 2004;44:585–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kano M, Hashimoto K, Chen C, Abeliovich A, Aiba A, Kurihara H, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Tonegawa S. Impaired synapse elimination during cerebellar development in PKC gamma mutant mice. Cell. 1995;83:1223–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sossin WS. Isoform specificity of protein kinase Cs in synaptic plasticity. Learn Mem. 2007;14:236–46. doi: 10.1101/lm.469707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hongpaisan J, Sun MK, Alkon DL. PKC ε activation prevents synaptic loss, Aβ elevation, and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:630–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5209-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim H, Han SH, Quan HY, Jung YJ, An J, Kang P, Park JB, Yoon BJ, Seol GH, Min SS. Bryostatin-1 promotes long-term potentiation via activation of PKCα and PKCε in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2012;226:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porro F, Rosato-Siri M, Leone E, Costessi L, Iaconcig A, Tongiorgi E, Muro AF. beta-adducin (Add2) KO mice show synaptic plasticity, motor coordination and behavioral deficits accompanied by changes in the expression and phosphorylation levels of the alpha- and gamma-adducin subunits. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9:84–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabenstein RL, Addy NA, Caldarone BJ, Asaka Y, Gruenbaum LM, Peters LL, Gilligan DM, Fitzsimonds RM, Picciotto MR. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in mice lacking beta-adducin, an actin-regulating protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2138–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3530-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bednarek E, Caroni P. β-Adducin is required for stable assembly of new synapses and improved memory upon environmental enrichment. Neuron. 2011;69:1132–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pielage J, Bulat V, Zuchero JB, Fetter RD, Davis GW. Hts/Adducin controls synaptic elaboration and elimination. Neuron. 2011;69:1114–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]