Abstract

A direct physical interaction of the prion protein isoforms is a key element in prion conversion. Which sites interact first and which parts of PrPc are converted subsequently is presently not known in detail. We hypothesized that structural changes induced by PrPSc interaction occur in more than one interface and subsequently propagate within the PrPC substrate, like epicenters of structural changes. To identify potential interfaces we created a series of systematically-designed mutant PrPs and tested them in prion-infected cells for dominant-negative inhibition (DNI) effects. This showed that mutant PrPs with deletions in the region between first and second α-helix are involved in PrP-PrP interaction and conversion of PrPC into PrPSc. Although some PrPs did not reach the plasma membrane, they had access to the locales of prion conversion and PrPSc recycling using autophagy pathways. Using other series of mutant PrPs we already have identified additional sites which constitute potential interaction interfaces. Our approach has the potential to characterize PrP-PrP interaction sites in the context of prion-infected cells. Besides providing further insights into the molecular mechanisms of prion conversion, this data may help to further elucidate how prion strain diversity is maintained.

Keywords: PrPC-PrPSc interaction, prion conversion, dominant-negative inhibition, interaction interface, epicenter of structural changes

Introduction

Prions are unconventional pathogens devoid of a nucleotide genome. Nevertheless, a variety of prion strains have been characterized which can be explained by the existence of a quasi-species population of conformers. The epigenetic information for encoding a diversity of prion strains is therefore enciphered in the structure of the prion protein (PrP). Stable inheritance over generations is achieved by the high fidelity of the template-assisted refolding of the substrate PrPC into the abnormal isoform PrPSc, which is both template and reaction product in prion conversion.1,2 In general, genetic information on nucleotide genomes is encoded as “digital information” enciphered with a very limited number of bases. Obviously, this mechanism greatly contributes to stable inheritance, while the diversity of genes is achieved by permutation in the sequence patterns of the bases. On the other hand, variations in protein conformation as underlying prion strain diversity seem to be “analog media” rather than digital. How strain diversity and stable inheritance is achieved at the molecular level is presently not well understood, if at all. A better molecular understanding of the modalities of the PrPC-PrPSc interaction and conversion reactions are prerequisites for this. We started to characterize this interaction in prion-infected cultured cells and recently reported a PrP region which constitutes a potential interface in PrPC-PrPSc interaction.3 Here, we are going to present our overarching working hypothesis which goes beyond the published work and future directions of this project.

Does a PrPc-PrPSc Interaction Site Define Epicenters of Structural Changes in PrP?

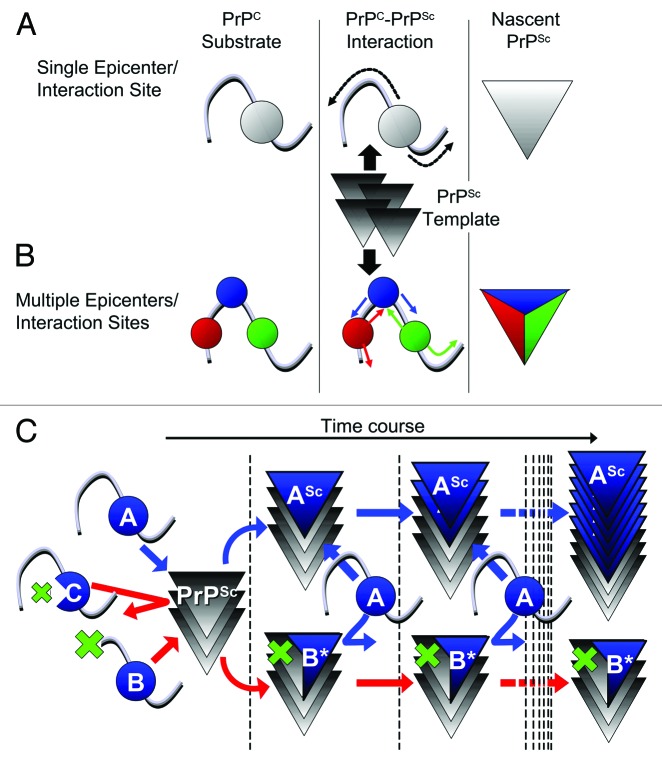

Our rationale for defining interfaces of the PrPC-PrPSc interaction is based on the hypothesis that regions within the PrPC substrate which strongly bind to the PrPSc template are the regions which also undergo initial regional structural changes. Subsequently, these intra-molecular structural changes propagate to adjacent regions until PrPC is converted, functioning thereby as “epicenters” of structural changes. The viewpoint that substantial regional structural changes also occur in conversion-incompetent PrP is supported by production of PK-resistant short fragments in in-vitro conversion of conversion-incompetent N-terminally truncated PrP.4,5 We hypothesized that such an epicenter would be a region whose regional structural changes as induced by template PrPSc, along with high-affinity adhesion, are independent of the global conversion or regional structural changes in other regions (Fig. 1A, B), and reasoned that such regions might also act as the interaction interfaces between conversion-incompetent mutant PrP and template PrPSc in dominant-negative inhibition (DNI).

Figure 1. (A, B) Schemes illustrating differences between “single epicenter/interaction site model” and “multiple epicenters/interaction sites model.” (A) Single epicenter/interaction interface model: PrPC substrate interacts with PrPSc template at a specific region, irrespective of the strain type, and structural changes spread from this interaction interface to the entire molecule, acting as an epicenter of structural changes. (B) Multiple epicenter/interaction interface model: PrPC substrate can interact with PrPSc template at more than one region and structural changes spread from each epicenter until the entire molecule is converted. (C) Scheme illustrating hypothetic mechanism of dominant-negative inhibition (DNI) when conversion -competent and -incompetent PrPC coexist. The interaction interface of PrPC is represented by a “blue ball.” The blue and red arrows indicate situations where the competition for PrPSc template was won by conversion-competent or conversion-incompetent PrPC, respectively. At the beginning, molecules with an intact interaction interface can bind the PrPSc template irrespective of their conversion abilities, i.e., conversion-competent PrP, “A,” or conversion-incompetent PrP with a defect outside the interface, “B,” can bind, whereas conversion-incompetent PrP with a defect in the interface, “C,” cannot even interact. After binding, “A” converts to a nascent PrPSc “ASc,” while “B” undergoes regional structural changes to become “B*” for high-affinity binding. The PrPSc template bound by “B*” cannot function as the template anymore, consequently inhibiting conversion of “A.”

DNI is a phenomenon where a conversion-incompetent PrP inhibits conversion of a co-existing conversion-competent PrPC substrate, presumably by competing for the PrPSc template (Fig. 1C). DNI was initially used to test high-affinity binding of conversion-incompetent PrPC to the postulated “factor X.”6 However, more recent in vitro conversion reactions demonstrated that DNI involves interaction of PrP substrate, inhibitory conversion-incompetent PrP and PrPSc template, even in the absence of any cellular components, suggesting that the process is independent of the postulated “factor X.”7,8 Of note, conversion incompetence is not synonymous with efficient DNI: some conversion-incompetent PrPs exert efficient DNI, whereas others do not,6,9 as was also observed in our recently published work presented below.3 We attributed the variations in DNI efficiency to their differential affinities for the PrPSc template, based on the functionality of their interaction interfaces (Fig. 1C, compare PrP ‘B’ and ‘C’). Assuming that the affinity for PrPSc is modulated by resulting regional structural changes in or around the interaction interface, we considered this region as a possible epicenter region. An epicenter region can then be identified as an interaction interface for DNI by evaluating DNI efficiencies of systematically-designed PrPs with mutations in or around the candidate region. Our model does not incorporate alternative mode of actions and we presently only have indirect experimental evidence that an interaction interface as defined in DNI is in fact equivalent to the interaction interface between PrPC substrate and PrPSc template in prion conversion. It is also possible that DNI works “indirectly,” either through an allosteric effect or by inhibiting polymerization in later steps. For the sake of clarity, such possibilities are not considered in Figure 1. We also expect that DNI is both strain and species specific as observed before when testing mutant PrPs with insertions in murine cell lines infected with different mouse prion strains.10

We did our analysis in persistently prion-infected cells as this provides authentic PrPSc and prion infectivity. Second the environment where the PrPC-PrPSc conversion occurs is most similar to the in vivo situation, including pH and non-proteinaceous factors, and conditions are maintained constant as long as the same cell line is used. Third, PrPC substrate and mutant PrP undergo similar post-translational maturation, e.g., glycosylation and GPI anchoring, and subcellular trafficking, although our later studies showed that glycosylation and trafficking can be different from wild-type PrP.

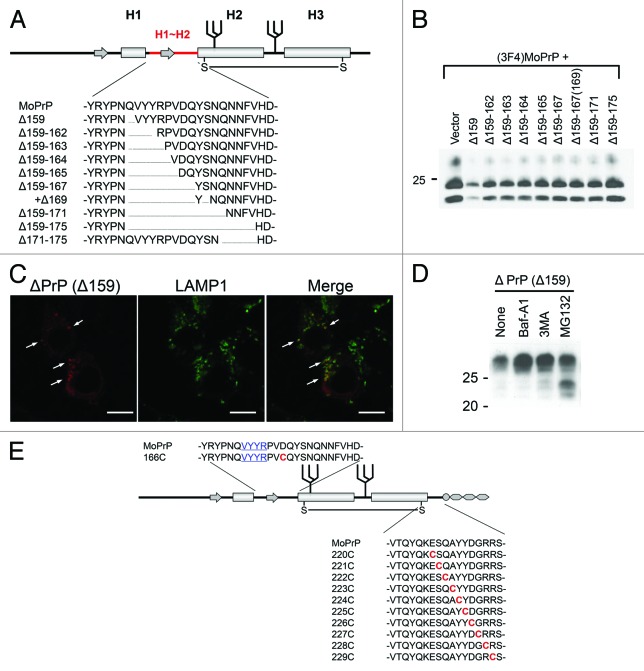

H1~H2 Region is Involved in PrP-PrP Interaction and Prion Conversion

Based on our hypothesis, we created a series of conversion-incompetent mutant PrPs with internal deletions of different length in the region between the first (H1) and second (H2) α-helix (H1~H2) (Fig. 2A) and evaluated their DNI efficiencies. As a result, DNI efficiencies showed an inverse relation with the size of the deletion (Fig. 2B), suggesting that this region might be a possible interaction interface itself or a critical component of it. Even mutant PrPs which lack the entire part from the pre-octapeptide repeat region to H1 depended on H1~H2 for efficient DNI. On the other hand, deletion from the C-terminal end of H1~H2 highly affected DNI. Deleting five residues there (Δ171–175) resulted in a similar inefficient DNI as deleting the entire 17 residues (Δ159–175). A single deletion of residue 175 also significantly affected DNI efficiency. These findings imply that some cooperation between H1~H2 and the region C-terminal to it is significant for efficient DNI. Our analysis also lead to new findings in the cell biology of prion proteins. The ability to exert DNI requires physical interaction with PrPSc in a cellular compartment where conversion of PrPc into PrPSc occurs. To reconcile the paradox of how an intracellular PrP can exert DNI, we showed that mutant PrPs are subject to both proteasomal and lysosomal/autophagic degradation pathways (Fig. 2D). Using autophagy pathways a fraction of mutant PrPs reaches the cellular locale of prion conversion (Fig. 2C), shedding light on the subcellular sites where prion conversion can occur and on PrPc/PrPSc recycling pathways.

Figure 2. (A) Example of systematically-designed mutant PrPs with deletions in H1~H2, used to test in DNI assay whether the H1~H2 region is an interaction interface. (B) Representative immunoblot demonstrating inverse correlation between DNI efficiency and size of deletion in H1~H2. A conversion-competent and epitope-tagged wild-type PrP, (3F4)MoPrP, and a conversion-incompetent PrP mutant were co-transfected into 22L prion-infected N2a cells and PK-resistant PrP was detected. (C) Confocal image showing co-localization of PrPΔ159 and LAMP1. N2a cells transfected with PrPΔ159 were fixed, treated with 6M guanidine hydrochloride to remove excessive PrPΔ159 signal localized in ER, labeled with antibodies against PrP and LAMP1, and analyzed for co-localization. (D) Immunoblot showing that degradation of PrPΔ159 is inhibited by treatment with bafilomycin A1 (Baf-A1), autophagy inhibitor 3MA, or proteasome inhibitor MG132. (E) A schematic illustration of a series of mutant PrPs with two cysteine substitutions.

Is There Evidence for the Importance of H1~H2 Region as PrP-PrP Interaction Site from Other Studies?

Recently, Singh and colleagues studied in vitro synthesized mouse PrP fibrils by hydrogen/deuterium (H/D)-exchange analysis and suggested that a region encompassing residues 159 to 225 (they referred to as amyloid core) might first convert to the amyloid form and then structural changes in other parts including the region N-terminal to H1 follow.11 Although experimental conditions for in vitro PrP fibril formation and PrPC-PrPSc conversion in cultured cells are very different, this supports the viewpoint that the region which first interacts with the PrPSc template undergoes structural changes before structural changes in other regions occur. Interestingly, the amyloid core defined by these authors also started with residue 159 and covered the entire H1~H2 region. The involvement of the region C-terminal to H1~H2 for efficient DNI we observed might reflect the importance of this region in the conversion of the amyloid core. In addition, a substantial part of this postulated amyloid core region was found protected in H/D-exchange analysis of products from seeded–or unseeded protein misfolding chain amplification (PMCA)12 and in PrPSc purified from prion-infected transgenic mice expressing PrP without a GPI anchor,13 although with variations in the areas that were protected. The region corresponding to the amyloid core was also identified as 11~12 kDa fragments after PK digestion of PrP fibrils composed of full-length recombinant PrP14 and similar fragments were seen in some types of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.15 These findings suggest that this region has a strong propensity to undergo structural changes and to polymerize in the presence of PrPSc or PrP fibrils. Interestingly, all of those C-terminal derived fragments more or less contained H1~H2, indicating importance of H1~H2 in the conversion to fibrils or PrPSc. Mutations in H1~H2, specifically S170N and N174T, have been recently reported to enhance aggregation propensity of PrP, again corroborating the importance of this region for PrP-PrP interactions.16,17

Taken together, these data are in line with our findings, despite being produced with very distinct methodologies. This confirms our approach of using DNI of systematically designed mutant PrPs in prion-infected cultured cells for identifying putative PrP-PrP interaction interfaces.

Are There Other Interaction Sites or Epicenters?

There is experimental evidence that the region N-terminal to H1~H2 also has a strong propensity to aggregate, as demonstrated when testing fibril formation of a naturally occurring PrP mutation, Y145stop. Synthetic amyloid fibrils encompassing residues 107–143 enhanced fibril formation of full-length PrP18 and this region might also contribute to the structural complexity of PrP fibrils and to strain barriers.19,20 Protection of the region N-terminal to H1 in H/D-exchange has been reported for PrP fibrils,21 PrPSc-seeded PMCA products,12 and PrPSc purified from prion-infected mice.13 Existence of multiple interfaces would introduce some “digital” characteristics to the PrPC-PrPSc conversion reaction. On one side this would contribute to high fidelity in prion replication. On the other hand, some structural variability by differential predominance of structural changes or usage of epicenters would be facilitated, equivalent to genetic information. This might explain the presence of short fragments of ~7 kDa in certain types of prion diseases, e.g., Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome, variably-protease-sensitive prionopathy, or Nor98,22 and provide a clue why mice expressing chimeric PrP are more susceptible to certain prion types and less susceptible to others than mice expressing wild-type PrP.23-25

We are presently looking for such additional interaction sites (Fig. 1B) and are studying the cooperation between H1~H2 and the region C-terminal to it. To do so, we created another series of mutant PrPs which have two cysteine substitutions (residue 166 and 220–229), providing an extra disulfide bond when in sufficient proximity (Fig. 2E). We expect that PrPs with two cysteine substitutions and a Δ159 deletion also will provide important answers whether DNI effects are mediated directly by competition for a PrPc-PrPSc interaction site or indirectly via allosteric effects. In preliminary studies some of these mutant PrPs exerted efficient DNI when co-transfected into prion-infected cells. These results also suggest that DNI by ΔPrPs and conversion into PrPSc isoforms are closely related, very likely because of using the same interaction interfaces. Combining now these mutants with other deletions will allow us to study the functionality of additional PrP-PrP interaction interfaces and to analyze how this impacts prion strain properties when using different strains.

Conclusions

Our approach can be used for characterizing PrP-PrP interaction sites in the context of prion-infected cells. Besides providing further insights into the molecular mechanisms of prion conversion, this strategy may help to elucidate how prion strain diversity is generated and maintained. Identification of interaction interfaces has also translational implications, as it might provide novel therapeutic targets. If a small chemical compound which binds to the interface region and inhibit its function as interaction interface is developed, it might represent an efficient anti-prion drug.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Schatzl laboratory for stimulating discussion. This work was supported by grants for the National Institute of Health R01 NS076853-01A1 and the Alberta Prion Research Institute (AB, Canada), and was performed within the framework of the Wyoming Endowed Excellence Chair.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

normal isoform of PrP

- PrPSc

abnormal isoform of PrP

- H1

first α-helix of PrP

- H2

second α-helix of PrP

- H1~H2

region between H1 and H2

- DNI

dominant-negative inhibition

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- PK

proteinase K

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- N2a

Neuro2a mouse neuroblastoma cells

- 22L-ScN2a

N2a cells persistently infected with 22L prions

References

- 1.Telling GC, Parchi P, DeArmond SJ, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R, Mastrianni J, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P, Prusiner SB. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science. 1996;274:2079–82. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taguchi Y, Mistica AMA, Kitamoto T, Schätzl HM. Critical significance of the region between Helix 1 and 2 for efficient dominant-negative inhibition by conversion-incompetent prion protein. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003466. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson VA, Priola SA, Wehrly K, Chesebro B. N-terminal truncation of prion protein affects both formation and conformation of abnormal protease-resistant prion protein generated in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35265–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawson VA, Priola SA, Meade-White K, Lawson M, Chesebro B. Flexible N-terminal region of prion protein influences conformation of protease-resistant prion protein isoforms associated with cross-species scrapie infection in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13689–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaneko K, Zulianello L, Scott M, Cooper CM, Wallace AC, James TL, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Evidence for protein X binding to a discontinuous epitope on the cellular prion protein during scrapie prion propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CI, Yang Q, Perrier V, Baskakov IV. The dominant-negative effect of the Q218K variant of the prion protein does not require protein X. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2166–73. doi: 10.1110/ps.072954607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geoghegan JC, Miller MB, Kwak AH, Harris BT, Supattapone S. Trans-dominant inhibition of prion propagation in vitro is not mediated by an accessory cofactor. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000535. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zulianello L, Kaneko K, Scott M, Erpel S, Han D, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Dominant-negative inhibition of prion formation diminished by deletion mutagenesis of the prion protein. J Virol. 2000;74:4351–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.9.4351-4360.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geissen M, Mella H, Saalmüller A, Eiden M, Proft J, Pfaff E, Schätzl HM, Groschup MH. Inhibition of prion amplification by expression of dominant inhibitory mutants--a systematic insertion mutagenesis study. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:40–7. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh J, Udgaonkar JB. Dissection of conformational conversion events during prion amyloid fibril formation using hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smirnovas V, Kim J-I, Lu X, Atarashi R, Caughey B, Surewicz WK. Distinct structures of scrapie prion protein (PrPSc)-seeded versus spontaneous recombinant prion protein fibrils revealed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smirnovas V, Baron GS, Offerdahl DK, Raymond GJ, Caughey B, Surewicz WK. Structural organization of brain-derived mammalian prions examined by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:504–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bocharova OV, Breydo L, Salnikov VV, Gill AC, Baskakov IV. Synthetic prions generated in vitro are similar to a newly identified subpopulation of PrPSc from sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1222–32. doi: 10.1110/ps.041186605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou W-Q, Capellari S, Parchi P, Sy M-S, Gambetti P, Chen SG. Identification of novel proteinase K-resistant C-terminal fragments of PrP in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40429–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyle LM, John TR, Schätzl HM, Lewis RV. Introducing a rigid loop structure from deer into mouse prion protein increases its propensity for misfolding in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutta A, Chen S, Surewicz WK. The effect of β2-α2 loop mutation on amyloidogenic properties of the prion protein. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:2918–23. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatterjee B, Lee C-Y, Lin C, Chen EH-L, Huang C-L, Yang C-C, Chen RP-Y. Amyloid core formed of full-length recombinant mouse prion protein involves sequence 127-143 but not sequence 107-126. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surewicz WK, Jones EM, Apetri AC. The emerging principles of mammalian prion propagation and transmissibility barriers: Insight from studies in vitro. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:654–62. doi: 10.1021/ar050226c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore RA, Herzog C, Errett J, Kocisko DA, Arnold KM, Hayes SF, Priola SA. Octapeptide repeat insertions increase the rate of protease-resistant prion protein formation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:609–19. doi: 10.1110/ps.051822606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh J, Sabareesan AT, Mathew MK, Udgaonkar JB. Development of the structural core and of conformational heterogeneity during the conversion of oligomers of the mouse prion protein to worm-like amyloid fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2012;423:217–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pirisinu L, Nonno R, Esposito E, Benestad SL, Gambetti P, Agrimi U, Zou W-Q. Small ruminant nor98 prions share biochemical features with human gerstmann-sträussler-scheinker disease and variably protease-sensitive prionopathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taguchi Y, Mohri S, Ironside JW, Muramoto T, Kitamoto T. Humanized knock-in mice expressing chimeric prion protein showed varied susceptibility to different human prions. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2585–93. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korth C, Kaneko K, Groth D, Heye N, Telling G, Mastrianni J, Parchi P, Gambetti P, Will R, Ironside J, et al. Abbreviated incubation times for human prions in mice expressing a chimeric mouse-human prion protein transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627989100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamgüney G, Giles K, Oehler A, Johnson NL, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Chimeric elk/mouse prion proteins in transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:443–52. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.045989-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]