Abstract

Objectives

Those with any psychiatric diagnosis have substantially greater rates of smoking and are less likely to quit smoking than those with no diagnosis. Using nationally representative data, we sought to provide estimates of smoking and longitudinal cessation rates by specific psychiatric diagnoses and mental health service utilization.

Design and participants

Data were analyzed from a two-wave cohort survey of a U.S. nationally representative sample (non-institutionalized adults): the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC; 2001-2002, n = 43,093; 2004-2005, n = 34,653).

Main outcome measures

We examined smoking rates (lifetime, past year, and past year heavy) and cross-sectional quit rates among those with any lifetime or past-year psychiatric diagnosis (DSM-IV). Importantly, we examined longitudinal quit rates and conducted analyses by gender and age categories.

Results

Those with any current psychiatric diagnosis had 3.23 [95% CI, 3.11 to 3.35] times greater odds of currently smoking than those with no diagnosis, and were 25% less likely to have quit by follow-up (95% CI=20% to 30%). Prevalence varied by specific diagnoses (32.4% to 66.7%) as did cessation rates (10.3% to 17.9%). Co-morbid disorders were associated with higher proportions of heavy smoking. Treatment utilization was associated with greater prevalence of smoking and lower likelihood of cessation.

Conclusions

Those with psychiatric diagnoses remained much more likely to smoke and less likely to quit, with rates varying by specific diagnosis. Our findings highlight the need to improve our ability to address smoking and psychiatric co-morbidity both within and without healthcare settings. Such advancements will be vital to reducing mental illness-related disparities in smoking, and continuing to decrease tobacco use globally.

Keywords: nicotine, tobacco, mental illness, psychiatric, smoking

INTRODUCTION

Current cigarette smokers are about half as likely to live to the age of 79 as individuals who never smoked.[1] Those with psychiatric diagnoses are at increased risk of experiencing smoking-related morbidity and mortality, due to exceptionally high rates of smoking in this sub-population. Lasser et al. (2000) found that 41.0% of those with a psychiatric diagnosis currently smoked, indicating nearly two-fold greater prevalence than among those with no diagnosis (22.5%). Moreover, smokers with a diagnosis accounted for approximately 44.3% of cigarettes smoked in the U.S. Cross-sectional cessation rates (i.e., lifetime smokers who were no longer current smokers) were lower among those with a diagnosis than among those without (30.5% compared to 42.5%).

These estimates were based on data from 1990-1992 (National Comorbidity Survey; NCS). Researchers have since examined differences in smoking based on mental illness using more current data.[2, 3] For example, using the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Wave 1 (2001-2002), Grant et al. found that, depending on specific diagnoses, those with psychiatric disorders were 2 to 16 times more likely to have nicotine dependence than those without these diagnoses.[3] Lawrence and colleagues (2009) used data from the National Comorbidity Survey – Replication (NCS-R; 2001-2003) and the 2007 Australian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing to update and extend findings from Lasser et al. (2000); and corroboratively found high rates of smoking among those with specific psychiatric disorders. Importantly, though, neither Grant et al. (2004) nor Lawrence et al. (2009) compared smoking cessation rates among those with psychiatric disorders. Using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2009-2011 surveys,[2] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that adults with mental illness had substantially higher rates of smoking (36.1% compared to 21.4% without mental illness) and lower rates of cessation. However, general mental illness (defined as non-specific psychological distress) was examined rather than specific DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses. This is a highly relevant limitation, given important differences in smoking based on specific diagnoses.[4] A limitation of both Lasser et al. (2000) and the CDC report is that both investigations utilized cross-sectional data to examine cessation rates, rather than longitudinal data. Cross-sectional quit rates may be influenced by a number of historical factors, while longitudinal quit rates provide more accurate estimates of current differences.

The primary purpose of this study was to update and extend previous estimates of smoking and cessation among those with psychiatric diagnoses. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is the most recent longitudinal nationally representative survey with data on DSM psychiatric diagnoses and smoking cessation.[5, 6] The use of the NESARC has several advantages: significantly larger sample (n=43,093) than other national datasets with psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., NCS, n= 4,411), standard measures of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation, [2, 7, 8] and longitudinal study design. The aims of the current investigation were to: 1) estimate differences in smoking prevalence and quitting based on specific psychiatric diagnoses, 2) examine quit rates using longitudinal data, 3) study whether prevalence of heavy smoking increased with greater numbers of diagnoses, 4) examine differences in smoking among psychiatric diagnoses based on gender and age categories, and 5) among those with psychiatric diagnoses, examine smoking rates and cessation by mental health treatment utilization.

METHODS

Study sample

The NESARC (Wave 1: 2001-2002, n = 43093; Wave 2: 2004-2005, n = 34,653) is a survey of U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized adults, administered with face-to-face, computer-assisted interviews in respondents households. Self-identified African Americans/Blacks, Hispanics, and young adults were oversampled. The data were weighted to adjust for household and personal non-response, and to be representative of the U.S. population (for a detailed account of the NESARC methodology, see [5, 6]). A subset of the original sample were contacted to participate in wave 2 (n = 39,959; those who were not deceased, deported, mentally or physical impaired, or on active duty in the armed forces). The response rate for the second wave of data collection was 86.7%, and there was a mean of 36.6 months between interviews.

Measures

Psychiatric diagnoses

Axis I and Axis II diagnoses were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule, DSM-IV version (AUDADIS-IV). [9, 10] The AUDADIS has demonstrated good-to-excellent reliability and validity in previous investigations.[10, 11] Lifetime diagnoses for Axis I and Axis II disorders included: major depression, dysthymia, mania and hypomania; generalized anxiety, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and specific phobia; and alcohol abuse or dependence, drug abuse or dependence, and antisocial personality/conduct disorder. For lifetime psychotic disorder or episode, respondents were asked, “Did a doctor or other health professional ever tell you that you had schizophrenia or a psychotic illness or episode?” We separately examined past year diagnoses for these disorders, with the exception of antisocial personality/conduct disorder and psychotic disorder/episode. Past year diagnoses were defined as the presence of a lifetime diagnosis with active symptoms (enough to qualify for a continuing diagnosis) during the past year, as well as new diagnoses.

Cigarette Smoking

Using standard definitions, [2, 7] lifetime smokers reported having ever smoked 100 or more cigarettes; current smokers further reported having smoked during the past year, based on Wave 1 data.

We defined cessation as long-term (at least one year) abstinence from all measured forms of tobacco (cigarettes, cigars, pipe, snuff, and chewing tobacco).[12] Using this definition, we generated measures of both cross-sectional quit rates (lifetime smokers, no current tobacco use at Wave 1) and longitudinal quit rates (Wave 1 smokers, no current tobacco use at Wave 2). We defined heavy smoking as 24 or more cigarettes per day.[13]

Treatment utilization

Lifetime utilization of mental health services was assessed at Wave 1 for the following psychiatric diagnoses: alcohol abuse/dependence, drug abuse/dependence, depression, dysthymia, mania, panic disorder, general anxiety, social phobia, and specific phobia. For those with each of these lifetime diagnoses, respondents were asked if they ever had sought help through the following avenues: counselor/therapist/doctor, emergency room, inpatient hospital, and prescribed medications. We created a summary binary variable, coded 0 for not having sought any help and 1 for having sought any help.

Analyses

We conducted analyses using Stata Statistical Software: Release 12, [14] accounting for the NESARC survey design in all estimates. We first estimated prevalence and cessation rates for the following groups: 1) no diagnosis, 2) any lifetime diagnosis, and 3) any past year diagnosis. We then calculated these estimates for each specific lifetime and current diagnosis. We examined the significance of all bivariate associations using Wald tests. We also calculated the prevalence of light-moderate smoking (0-23 cigarettes per day) and heavy smoking (≥ 24 cigarettes per day) based on number of diagnoses (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+). We tested the significance of these differences using multinomial logistic regression. We first entered the variable for number of diagnoses as a categorical (0 diagnoses as reference) in order to estimate prevalence for each group and test the significance of differences from those with 0 diagnoses. We then entered this variable as continuous, to examine whether the likelihood of light/moderate or heavy smoking increased linearly with number of diagnoses. We used logistic regression to estimate associations between psychiatric diagnoses and lifetime smoking, current smoking, and cross-sectional quit rates, adjusting for age, gender, and education. These covariates were selected to account for associations between socio-demographic characteristics and both smoking and psychiatric diagnoses. We calculated relative risks for quitting by follow-up using generalized linear models, specifying a binomial distribution and a log link, and adjusting for the same socio-demographic covariates. We repeated our estimation of prevalence and bivariate associations for gender and age categories (see e-Tables 1-8 and e-Figs 1-2). In our final set of analyses, we selected for those who had current/lifetime mental illness, and examined associations between lifetime treatment utilization and smoking outcomes (prevalence and cessation) using the procedures outlined above. Regarding missing data, n = 444 wave 1 respondents (1.0 %) and n = 62 wave 2 respondents (< 1.0 %) had unknown current smoking status. These respondents were not included in the analyses. There was no missing data for any of the diagnostic variables. For all analyses, we used a significance cut-off of 0.001 to account for multiple testing.

RESULTS

Prevalence of smoking across lifetime and current psychiatric diagnoses and sociodemographic sub-groups are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Wave 1 Smoking by Psychiatric Diagnosis Status and Sociodemographic Sub-Groups

| No Diagnosis | Any Lifetime Diagnosis | Any Current Diagnosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % Lifetime smoker |

% Current smoker |

% Lifetime Smoker |

% Current Smoker |

% Lifetime Smoker |

% Current smoker |

|

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 28.3 | 13.8 | 50.8 | 31.2 | 51.8 | 35.3 |

| Men | 37.5 | 17.8 | 61.2 | 35.5 | 62.0 | 42.9 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-29 | 20.6 | 17.3 | 50.2 | 43.2 | 51.7 | 45.8 |

| 30-44 | 26.7 | 17.9 | 51.3 | 35.2 | 55.6 | 41.3 |

| 45+ | 40.3 | 13.5 | 63.3 | 27.0 | 62.9 | 31.3 |

| Race | ||||||

| White/Caucasian, non- Hispanic |

37.4 | 16.6 | 58.7 | 34.0 | 59.8 | 40.5 |

| Black/African American, non- Hispanic |

25.9 | 15.2 | 49.1 | 32.8 | 47.6 | 34.8 |

| Hispanic | 20.9 | 12.7 | 44.7 | 28.1 | 45.1 | 31.0 |

| Other | 20.9 | 12.4 | 54.0 | 35.7 | 54.3 | 41.0 |

| Education | ||||||

| <High school | 36.5 | 18.7 | 67.4 | 44.0 | 67.0 | 50.4 |

| High school graduate | 37.0 | 19.7 | 62.6 | 39.8 | 61.6 | 43.7 |

| Some college | 31.7 | 15.4 | 57.8 | 36.7 | 56.7 | 40.5 |

| College graduate | 26.2 | 10.1 | 45.7 | 22.0 | 46.9 | 27.5 |

| Family income, US $ | ||||||

| 0-19,999 | 32.2 | 16.5 | 58.8 | 41.1 | 58.6 | 45.4 |

| 20,000-34,999 | 35.0 | 17.8 | 61.0 | 40.0 | 61.1 | 44.1 |

| 35,000-69,999 | 34.1 | 16.0 | 56.8 | 32.9 | 55.2 | 37.3 |

| ≤70,000 | 27.7 | 11.6 | 49.7 | 22.8 | 52.4 | 28.4 |

| Treatment utilization a | --- | --- | ||||

| Yes | 60.3 | 38.7 | 61.1 | 42.9 | ||

| No | 54.1 | 30.5 | 51.8 | 35.2 | ||

Note: All estimates accounted for the NESARC survey design.

Treatment utilization was assessed for mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders only. When examining smoking prevalence among those with or without treatment utilization, we selected for those with these diagnoses only, rather than “Any Lifetime/Current Diagnosis.”

Prevalence of smoking and cessation rates by any lifetime or past year diagnoses

Current smoking prevalence rates were 15.5% for those with no diagnosis, compared to 33.4% for those with a lifetime diagnosis and 39.0% of those with a past year diagnosis (Table 2). Those with psychiatric diagnoses were less likely to have quit at follow-up (18.4% and 17.7% for lifetime and current diagnosis; compared to 22.3% for no diagnosis). These differences persisted after adjusting for age, gender, and education (Table 2). Those with a current diagnosis had 3.23 times greater odds of being a current smoker than those with no diagnosis (OR = 3.23, 95% CI = 3.11, 3.35); and current smokers with a diagnosis at Wave 1 were 25% less likely to stop using tobacco by Wave 2 (RR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.70, 0.80). Cross-sectional quit rates were lower for those with a diagnosis (36.5% and 28.6% for lifetime and current diagnosis, respectively; compared to 48.3% for no diagnosis).

Table 2.

Cigarette Smoking Status According to Psychiatric Diagnosis

| US Pop., |

Current Smoker | Lifetime Smoker, % | Cross-sectional Quit Rated |

Longitudinal Quit Ratee |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| %a | %a | ORb (95% CI) |

%a | ORb (95% CI) |

%a | ORb (95% CI) |

%a | RRc (95% CI) |

|

| Total | 100 | 24.3 | --- | 44.1 | --- | 40.9 | --- | 19.6 | --- |

| No diagnoses | 49.0 | 15.5 | Ref. | 32.3 | Ref. | 48.3 | Ref. | 22.3 | Ref. |

| Any lifetime diagnosis |

51.0 | 33.4† | 2.70† (2.62, 2.79) |

56.3† | 3.01† (2.92, 3.10) |

36.5† | 0.88† (0.84, 0.92) |

18.4† | 0.79† (0.75, 0.84) |

| Any past year diagnosis |

25.9 | 39.0† | 3.23† (3.11, 3.35) |

56.7† | 3.20† (3.09, 3.31) |

28.6† | 0.72† (0.68, 0.77) |

17.7† | 0.75† (0.70, 0.80) |

Note: All estimates accounted for the NESARC survey design.

Percentages were not adjusted for covariates

Odds ratios calculated using logistic regression. Estimates adjusted for age, gender, and education.

Relative risks calculated using general linear modeling, specifying a binomial distribution and log link. Estimates adjusted for age, gender, and education.

Defined as lifetime smokers who were not current smokers at the Wave 1 interview.

Defined as Wave 1 (2001-2002) current smokers who no longer smoked at Wave 2 (2004-2005).

Significantly different from respondents with no diagnosis, p < 0.001.

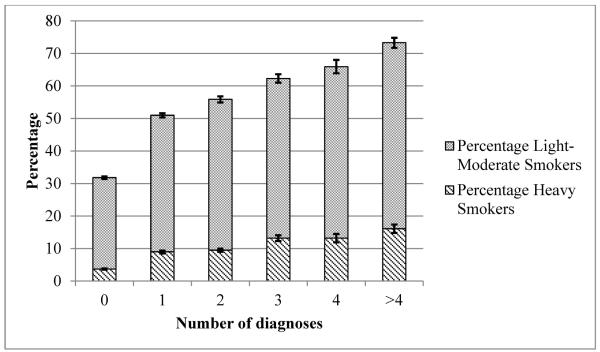

Prevalence of heavy smoking by count of psychiatric diagnoses

Compared to those with 0 diagnoses, those with multiple diagnoses had significantly greater likelihood of being a heavy smoker (Figure 1; all differences p < 0.001). For example, the proportion of heavy smokers among those with 0 diagnoses was 3.7%, compared to 16.1% for 4+ diagnoses). There was also a significant linear trend, whereby each additional diagnosis (from 1 to 4+) was associated with 67% greater odds of being a heavy smoker (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Heavy Smoking Rates by Number of Lifetime Diagnoses. All estimates accounted for the NESARC survey design. Statistical comparisons were made using multinomial logistic regression, with “0 diagnoses” as the reference group. Heavy smokers were defined as those whose usual cigarette consumption exceeded 24 cigarettes per day. Light to moderate smokers consumed 24 or less cigarettes per day. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% CI. There was also a significant linear trend for both light-moderate smokers (OR = 1.45; p < 0.001) and heavy smokers (OR = 1.68, p < 0.001; not displayed in figure).

Prevalence of smoking among those with specific lifetime or past year psychiatric diagnoses

Smoking prevalence (both lifetime and current) was significantly higher for those with each lifetime disorder than for those with no diagnosis (p < 0.001), and cross-sectionally and longitudinally assessed quit rates were significantly lower (p < 0.001) (Table 3). All past year diagnoses were associated with higher smoking prevalence and lower quit rates than those with no psychiatric disorders (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life

| Lifetime Diagnosis |

US Population, % |

Current Smoker, % |

Lifetime Smoker, % |

Cross-sectional Quit Rate, % |

Longitudinal Quit Rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Diagnosis | 49.0 | 15.5 | 32.3 | 48.3 | 22.3 |

| Any diagnosis | 51.0 | 33.4† | 56.3† | 36.5† | 18.4† |

| Social Phobia | 5.0 | 30.6† | 51.6† | 38.2† | 16.8† |

| Agoraphobia | 1.3 | 43.0† | 62.8† | 28.7† | 13.0† |

| Panic Disorder | 4.4 | 39.6† | 60.9† | 33.1† | 14.7† |

| Major Depression | 18.2 | 34.0† | 53.8† | 34.5† | 16.4† |

| Dysthymia | 4.9 | 39.9† | 60.2† | 32.2† | 14.1† |

| Specific Phobia | 9.5 | 33.0† | 52.7† | 35.1† | 18.7† |

| Psychotic Disorder or Episode |

0.8 | 49.8† | 69.1† | 26.9† | 12.5† |

| Alcohol Abuse or Dependence |

30.3 | 39.2† | 64.9† | 34.6† | 17.6† |

| Antisocial Personality, or Conduct Disorder |

4.7 | 52.4† | 69.7† | 21.7† | 17.3† |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

4.5 | 34.6† | 55.9† | 35.4† | 13.8† |

| Drug Abuse or Dependence |

10.3 | 53.6† | 75.4† | 25.7† | 15.4† |

| Mania or Hypomania |

6.0 | 43.7† | 58.2† | 22.7† | 15.5† |

All estimates and significance tests accounted for the NESARC survey design. Specific diagnoses were not mutually exclusive.

Significance tests conducted using Wald tests.

Compared to those with no diagnosis, difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the past year

| Past year Diagnosis |

US Population, % |

Current Smoker, % |

Lifetime Smoker, % |

Cross-sectional Quit Rate, % |

Longitudinal Quit Rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Diagnosis | 49.0 | 15.5 | 32.3 | 48.3 | 22.3 |

| Any Diagnosis | 25.9 | 39.0† | 56.7† | 28.6† | 17.7† |

| Social Phobia | 2.8 | 32.4† | 54.7† | 38.0† | 13.1† |

| Agoraphobia | 0.7 | 49.0† | 65.8† | 24.7† | 12.6† |

| Panic Disorder | 1.7 | 47.7† | 61.7† | 21.7† | 14.0† |

| Major Depression | 7.9 | 39.8† | 55.9† | 26.7† | 14.5† |

| Dysthymia | 2.3 | 43.7† | 60.9† | 26.8† | 10.3† |

| Specific Phobia | 7.2 | 34.5† | 53.5† | 33.3† | 17.9† |

| Psychotic Disorder or Episode |

--- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Alcohol Abuse or Dependence |

8.5 | 51.0† | 64.5† | 17.0† | 17.7† |

| Antisocial Personality, or Conduct Disorder |

--- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

2.3 | 42.4† | 56.9† | 23.9† | 13.5† |

| Drug Abuse or Dependence |

2.0 | 66.7† | 77.6† | 9.8† | 13.8† |

| Mania or Hypomania |

3.0 | 44.3† | 57.0† | 20.7† | 15.3† |

All estimates and significance tests accounted for the NESARC survey design. Specific diagnoses were not mutually exclusive.

Significance tests conducted using Wald tests.

Psychosis and antisocial personality/conduct disorder were only measured as lifetime occurrence

Compared to those with no diagnosis, difference was statistically significant, p < 0.001.

Mental health treatment utilization

Treatment utilization was assessed for alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Among those with a lifetime diagnoses in any of these categories, 35.5% of respondents reported seeking help for their disorder. Among those who ever sought help, there was a lifetime smoking prevalence of 60.2%, compared to 54.1% among those who had never sought help (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.24, 1.34). A similar pattern was found for current smoking, whereby those who sought help had a prevalence of 38.7%, compared to 30.5% among those who ever sought help (OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.39, 1.50). Lifetime smokers who ever sought help were less likely to have quit smoking by Wave 1 (33.0% vs. 38.9%; OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.82, 0.87) or by Wave 2 (16.3% vs. 19.7%; RR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.76, 0.90).

Among those with a past year diagnosis of these select disorders, 42.7% reported ever seeking help for their disorder. Those who sought help were more likely to be lifetime smokers (61.1% vs. 52.8%; OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.38, 1.54) and current smokers (42.9% vs. 35.2%; OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.30, 1.46). Lifetime smokers with a past year diagnosis who ever sought help were slightly less likely to quit smoking by Wave 1 (29.0% vs. 27.6%; OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.91, 1.00) or by Wave 2 (15.1% vs. 18.9%; RR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.71, 0.89).

Supplemental analyses: differences by gender and age categories

Supplemental analyses are reported in eTables 1-8, and eFigures 1 and 2 (online-only). Gender differences varied by specific diagnosis. Men tended to have higher smoking prevalence than women; however, women with a lifetime alcohol use disorder or conduct/antisocial personality disorder were more likely to currently smoke than men with these corresponding diagnoses. Men with a past-year diagnosis of agoraphobia, panic disorder, and specific phobia were less likely to stop using all forms of tobacco by follow-up than women (p < 0.001). Both men and women who sought help for their disorder were more likely to smoke and less likely to quit smoking than those who did not seek help, although these differences were slightly larger for men compared to women.

Regarding age differences, those in the youngest age group (18-29) typically had the highest rates of current smoking (compared to those in the 30-44 and 45+ age groups). This group also tended to be most likely to have quit at follow-up, with one exception: young adults with a current or lifetime diagnosis of Social Phobia were the least likely to have quit at follow-up among the three age categories (p < 0.001). Results for treatment-utilization analyses followed the same pattern as the general sample, with those who sought help having higher prevalence of smoking and lower quit rates than those who did not seek help, for all age groups.

DISCUSSION

In this U.S. nationally representative sample, smokers with current psychiatric disorders have substantially higher prevalence of smoking than those with no diagnosis (39.0% versus 15.5). Longitudinal quit rates indicated that those with psychiatric diagnoses had 25% lower likelihood of quitting by follow-up, compared to those without a diagnosis. These differences in smoking prevalence and cessation rates between those with and without diagnoses were consistent across sociodemographic sub-groups (e.g., income, education, and race/ethnicity), and remained significant after accounting for these sociodemographic variables as covariates. Prevalence was higher and quit rates were lower among those who had ever sought help for their disorder. Prevalence varied widely across specific disorders (23.4% to 66.7%), while there was somewhat less variation in quit rates (10.3% to 17.9%). Those with multiple lifetime diagnoses (40.1% of smokers) were more likely to smoke heavily than those with one or no diagnosis.

There was substantial overlap between psychiatric diagnoses in this study. This was evidenced by the high rates of psychiatric co-morbidity reported in the results. Smoking among those with psychiatric co-morbidity is an important issue, especially considering the particularly high rates of heavy smoking among those with multiple diagnoses, and the paucity of research that addresses this topic. Regarding specific diagnoses, we were unable to make statistical comparisons (due to overlapping diagnoses); however, there were notable trends in the findings. Consistent with previous research,[13, 15] we found the highest prevalence of smoking among those with current substance use disorders. Interestingly, we found those with alcohol use disorders had the lowest cross-sectional quit rates relative to other diagnoses (consistent with Lasser et al., 2000), but had among the highest prospective quit rates. This likely reflects the age composition of those with alcohol use disorders, with younger-adults more likely to have this diagnosis, and younger adults having the lowest cross-sectional quit rates and the highest longitudinal quit rates. This contradiction between cross-sectional and longitudinal quit rates highlights the methodological importance of examining cessation longitudinally, given the number of factors that can potentially influence commonly reported cross-sectional quit rates.

Cessation rates were generally lower among those with mood or anxiety disorder diagnoses. There was also a trend whereby those with disorders that are characterized by more consistent symptoms over time (e.g. dysthymia, generalized anxiety) had lower cessation rates than those with disorders characterized by more episodic symptom profiles (e.g., major depressive episode, panic disorder). This pattern of results was consistent with Lasser et al. (2000), and may be indicative of more difficulty with stopping tobacco use among those with disorders characterized by unremitting symptomatology.

Large portions of those with psychiatric disorders reported they had never sought treatment for their disorder. This was particularly true for some specific sociodemographic sub-categories. For example young-adults, despite being the age group with the highest prevalence of smoking, were the least likely to report having sought help for their disorders. This highlights the importance of studying and implementing public health interventions that reach smokers with psychiatric disorders outside of the healthcare system. As noted by multiple research groups,[4, 15, 16] population-level interventions have not been the focus of tobacco control efforts among those with psychiatric diagnoses to date. Research and interventions have nearly exclusively focused on mental health treatment settings, resulting in a paucity of research on how population-level interventions may influence smoking rates among those with psychiatric diagnoses. Lawrence and colleagues (2009) discussed of a number of reasons that current population-level tobacco control interventions may be less effective for those with mental illness. For example, smoking bans and associated stigma may contribute to social isolation among those with psychiatric disorders. Policy related to pricing may place a disproportionate financial burden on those with psychiatric disorders and their families. Interventions that focus on the negative health effects of smoking may be less influential among those with psychiatric disorders, who may place less value on long-term health outcomes.

Concordantly, a substantial portion of those with psychiatric diagnoses reported seeking help for their disorders, supporting the continued investigation of integrating and improving cessation interventions in mental health care settings. These efforts are ongoing – many psychiatric hospitals have banned cigarette smoking and implemented smoking cessation programs.[17] There is promising evidence for effective cessation therapies designed for those with specific diagnoses,[18, 19] and ample evidence that smokers with psychiatric co-morbidity are able to quit.[20] Yet, despite these advances, multiple recent investigations and reviews have noted that non-treatment remains the norm [21-23], and smoking bans in psychiatric settings have been ineffective at generating lasting smoking cessation.[17] Zeidonis et al. outlined several recommendations for improving smoking cessation outcomes in mental health care settings,[4] including: 1) study of the interaction of psychiatric and smoking cessation treatments, 2) adequate samples and power in smoking cessation trials, 3) the adaptation of smoking cessation treatments to psychiatric populations, and 4) integration of smoking cessation treatments within the current mental health treatment system.

The NESARC dataset was the most current and comprehensive dataset with which we could address the aims of this investigation. Still, there were limitations of this study to note. Although we were able to look at specific diagnoses, and categorize by reports of treatment utilization, the NESARC data was not designed to distinguish between varying levels of mental illness severity. Among those who reported ever seeking treatment, smoking rates were higher and quit were lower. It is likely that treatment utilization was a proxy for symptoms severity. Additionally, there was no information on whether the respondents were currently in treatment or the extent of treatment success. Thus, we were unable to examine smoking outcomes by these more nuanced characterizations of those with psychiatric diagnoses. The estimates in the current study were based on data from 2000-2005, reflecting the most recent available data on smoking and cessation in the U.S. rather than the current U.S. population. A limitation of this and other similar studies was that cigarette smoking and tobacco use measures were based on self-report; however, our broad definitions of smoking and tobacco use (any over the past year) would likely have reduced any recall-bias. This study did not include diagnoses for all Axis I and Axis II psychiatric disorders known to be associated with smoking (i.e. posttraumatic stress disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). However, misclassification of some individuals with disorders as having no diagnosis would have conservatively biased difference estimates. The study was based in the U.S. and it is unclear how the findings may generalize to other parts of the world.

In conclusion, those with psychiatric diagnoses were substantially more likely to smoke cigarettes, and among those who smoked, were less likely to stop using tobacco compared to those with no disorders. This was particularly true for those with co-morbid lifetime disorders, who made up nearly half of this nationally representative sample of smokers. Results varied by specific diagnoses, gender, and age categories, suggesting the influence of treatment and policy may vary based on these sub-groups as well. Continuing progress in reducing smoking in the U.S. will require advances in understanding the complexities of smoking among those with specific diagnoses and combinations of diagnoses, and the application of this knowledge to improving tobacco-control interventions and policies.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1 (online only): Heavy Smoking Rates by Number of Lifetime Diagnoses: Gender Differences. Statistical comparisons were made using multinomial logistic regression, with “0 diagnoses” as the reference group. Heavy smokers were defined as those whose usual daily cigarette consumption exceeded 24 cigarettes per day. Light to moderate smokers consumed 24 or less cigarettes per day. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% CI. †Proportions were significantly different from women, p < 0.05. Among women, the linear trends for both light-moderate smoking (OR = 1.46) and heavy smoking (OR = 1.73) were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Among men, the linear trends for both light-moderate smoking (OR = 1.45) and heavy smoking (OR = 1.66) were statistically significant.

eFigure 2 (online only): Heavy Smoking Rates by Number of Lifetime Diagnoses and the Proportion of Heavy Smokers: Age Group Differences. Heavy smokers were defined as those whose usual daily cigarette consumption exceeded 24 cigarettes per day. Light to moderate smokers consumed 24 or less cigarettes per day. Statistical comparisons were made using multinomial logistic regression, with “0 diagnoses” as the reference group. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% CI. †Proportions were significantly different by age category, p < 0.001. The linear trend for light-moderate smoking was significant for all three age groups (18-29: OR = 1.65; 30-44: OR = 1.52; 45+ = 1.38; p < 0.001), as was the linear trend for heavy smoking (18-29: OR = 2.24; 30-44: OR = 1.83; 45+ = 1.67; p < 0.001).

eTable 1. Smoking Status According to Psychiatric Diagnosis, by Gender

eTable 2. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by gender

eTable 3. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Gender

eTable 4. Smoking Status According to Psychiatric Diagnosis, by Age

eTable 5. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by Age

eTable 6. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by Age

eTable 7. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Age

eTable 8. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Age

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject:

Those with any psychiatric diagnosis have substantially greater prevalence of cigarette smoking than those with no diagnosis.

Those with any psychiatric diagnosis have greater difficulty quitting smoking than those with no diagnosis.

What this study adds:

This study used the most up-to-date available data source to estimate the extent of differences in smoking prevalence and cessation rates between those with specific psychiatric diagnoses and those with no psychiatric diagnoses among adults in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING The project described was supported by Grant Number P50 DA033945 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH), OD. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32-MH014235, PI: Heping Zhang), and Women’s Health Research at Yale. Study funders had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. All researchers were independent from funders.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted the work.

CONTRIBUTORSHIP All authors designed the study. PHS and SAM planned the analysis. PHS conducted study analysis and drafted the paper. All authors revised and edited the paper.

Contributor Information

Philip H Smith, Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale University, 2 Church St. South, New Haven, CT 06519, U.S..

Carolyn M Mazure, Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, Women’s Health Research at Yale, 135 College Street, Suite 220, New Haven, CT 06510, U.S..

Sherry A McKee, Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, 2 Church St. South, New Haven, CT 06519, U.S..

References

- [1].Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(4):341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital Signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged >= 18 years with mental illness: United States, 2009-2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2013;62(05):81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Halth report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Grant BF, Kaplan K. Source and accuracy statement for wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grant BF, Kaplan K, Shepard J, et al. Source and accuracy statement for wave 1 of the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bathesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital Signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged >= 18: United States, 2005-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2011;60(35):1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].NAQC . Measuring Quit Rates. In: An L, Betzner A, Luxenberg ML, et al., editors. Quality Improvement Initiative. Phoenix, AZ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Grant BF, Dawson DA. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular psychiatry. 2008;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Farkas AJ. Duration of smoking abstinence and success in quitting. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89(8):572. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP; College Station, Tx: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: Results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. 1. Vol. 9. BioMed Central Public Health; 2009. p. 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Williams JM, Ziedonis D. Addressing tobacco among individuals with a mental illness or an addiction. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(6):1067–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lawn S, Pols R. Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(10):866–885. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stapleton JA, Watson L, Spirling LI, et al. Varenicline in the routine treatment of tobacco dependence: a pre–post comparison with nicotine replacement therapy and an evaluation in those with mental illness. Addiction. 2008;103(1):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, et al. A placebo controlled trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2002;52(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Prochaska JJ. Failure to treat tobacco use in mental health and addiction treatment settings: A form of harm reduction? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(3):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Prochaska JJ. Smoking and Mental Illness — Breaking the Link. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(3):196–198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:297–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1 (online only): Heavy Smoking Rates by Number of Lifetime Diagnoses: Gender Differences. Statistical comparisons were made using multinomial logistic regression, with “0 diagnoses” as the reference group. Heavy smokers were defined as those whose usual daily cigarette consumption exceeded 24 cigarettes per day. Light to moderate smokers consumed 24 or less cigarettes per day. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% CI. †Proportions were significantly different from women, p < 0.05. Among women, the linear trends for both light-moderate smoking (OR = 1.46) and heavy smoking (OR = 1.73) were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Among men, the linear trends for both light-moderate smoking (OR = 1.45) and heavy smoking (OR = 1.66) were statistically significant.

eFigure 2 (online only): Heavy Smoking Rates by Number of Lifetime Diagnoses and the Proportion of Heavy Smokers: Age Group Differences. Heavy smokers were defined as those whose usual daily cigarette consumption exceeded 24 cigarettes per day. Light to moderate smokers consumed 24 or less cigarettes per day. Statistical comparisons were made using multinomial logistic regression, with “0 diagnoses” as the reference group. All comparisons were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Error bars represent 95% CI. †Proportions were significantly different by age category, p < 0.001. The linear trend for light-moderate smoking was significant for all three age groups (18-29: OR = 1.65; 30-44: OR = 1.52; 45+ = 1.38; p < 0.001), as was the linear trend for heavy smoking (18-29: OR = 2.24; 30-44: OR = 1.83; 45+ = 1.67; p < 0.001).

eTable 1. Smoking Status According to Psychiatric Diagnosis, by Gender

eTable 2. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by gender

eTable 3. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Gender

eTable 4. Smoking Status According to Psychiatric Diagnosis, by Age

eTable 5. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by Age

eTable 6. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis at Any Time in Their Life, by Age

eTable 7. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Age

eTable 8. Smoking Status among Respondents According to Psychiatric Diagnosis during the Past Year, by Age