Abstract

This study examined longitudinal associations of prenatal exposures as well as childhood familial experiences with obesity status from ages 10 to 18. Hierarchical generalized linear modeling (HGLM) was applied to examine 5,156 adolescents from the child sample of the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79). Higher maternal weight, maternal smoking during pregnancy, lower maternal education, and lack of infant breastfeeding were contributors to elevated adolescent obesity risk in early adolescence. However, maternal age, high birth weight of child, and maternal annual income exhibited long-lasting impact on obesity risk over time throughout adolescence. Additionally, childhood familial experiences were significantly related to risk of adolescent obesity. Appropriate use of family rules in the home and parental engagement in children’s daily activities lowered adolescent obesity risk, but excessive television viewing heightened adolescent obesity risk. Implementation of consistent family rules and parental engagement may benefit adolescents at risk for obesity.

Keywords: Adolescence, Familial experiences, Obesity, Prenatal risk exposure, Smoking

Introduction

Childhood obesity has become a critical public health problem as its prevalence has increased substantially in recent decades; an estimated 16.9% of children aged 2–19 years in the United States meet obesity status (Freedman, Khan, Serdula, Ogden, & Dietz, 2006; Hedley et al., 2004; Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010). Growing medical and social concerns over the large proportion of children affected by obesity have led to a wealth of empirical research aimed at identifying risk and protective factors, including those related to parental health, adverse prenatal exposures, and family environment (e.g., Reilly et al., 2005; Rhee, Lumeng, Appugliese, Kaciroti, & Bradley, 2006; Strauss & Knight, 1999). However, most prior studies on obesity risk have relied on cross-sectional data or data spanning a short period of time (e.g., Delva, Johnston, & O’Malley, 2007; Gillman et al., 2008; Mamun, Lawlor, O’Callaghan, Williams, & Najman, 2005; Whitaker, 2004), which have limited usefulness in assessing risk across developmental periods. Specifically, investigation of prenatal exposures (e.g., maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy) as well as aspects of the family environment of children not specific to nutrition (e.g., existence of family rules, levels of parental control and engagement) have not yet been examined concurrently in respect to obesity risk across the adolescent years. Considering that prenatal exposures and childhood familial experiences may play different roles in regard to obesity risk over time, it is important to examine these factors together and evaluate associations longitudinally. This study assessed these associations from the prenatal period through adolescence to inform prevention/intervention efforts to reduce obesity risk in children.

Prior studies have identified key socio-demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity and household income, as predictors of childhood obesity. It is well-established that children with a low socioeconomic status (SES) have a higher prevalence of obesity (Delva, Johnston, & O’Malley, 2007; O’Dea & Caputi, 2001; Wang & Zhang, 2006). Also, obesity prevalence among Hispanic boys is significantly higher than among White boys; and African American girls, compared to White girls, are more likely to become obese (Ogden et al., 2010). In addition to socio-demographic characteristics, past research has reported potentially modifiable factors during the prenatal period and at the child’s birth that have been linked to future obesity risk in children. A systematic review of 14 observational studies (Oken, Levitan, & Gillman, 2008) found that children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy exhibited higher obesity risk in their childhood, compared to children whose mothers did not smoke during pregnancy. It also appears that maternal smoking during pregnancy lowers fetal growth but increases postnatal weight gain (e.g., Hill, Shen, Locke Wellman, Rickin, & Lowers, 2005; Power & Jefferis, 2002). One study examining the long-term effect of maternal smoking in pregnancy on obesity risk from ages 7 to 33 reported that maternal smoking in pregnancy was associated with increased obesity risk at age 11 for females and 16 for males, as well as at age 33 for both genders (Power & Jerreris, 2002), suggesting a robust relationship over time.

Additionally, maternal weight is a strong predictor of offspring obesity (e.g., Francis, Ventura, Marini, & Birch, 2007; Mamun et al., 2005; Reilly et al., 2005). For instance, maternal obesity in early pregnancy doubles obesity risk for children aged 2 to 4 years (Whitaker, 2004). In addition to genetic influences, maternal obesity status may be associated with child obesity through mothers’ influence on children’s eating behavior and physical activity (e.g., Francis et al., 2007).

Furthermore, birth weight is an indicator of the conditions experienced in utero and may serve as a mediator between prenatal influences and obesity in later life. Both high and low birth weights are associated with later obesity. A high birth weight is positively linked with later body mass index (BMI) and consistently associated with increased risk of childhood and adult obesity (Persons, Sevdy, & Nichols, 2008). The link between low birth weight and obesity may be the result of accelerated growth immediately after birth (McCarthy et al., 2007). In addition, prior studies have reported that infant breastfeeding may protect children against obesity in later life (CDC, 2007; Owen, Martin, Whincup, Smith, & Cook, 2005).

In sum, prior studies have reported independent associations of each of these factors with later obesity. However, determining the relative importance of these factors in association with changes in body mass index (BMI) and prevalence of obesity status has been hindered because of a lack of comprehensive measures that access these factors simultaneously. A comprehensive study that simultaneously examines the relations of these factors with obesity trajectories over time is likely to make significant contributions to the literature.

Moreover, in addition to the nutritional bases of obesity, there has been considerable discussion of other aspects of familial contributors to obesity. For example, excessive television viewing and a lack of family rules, parental control, and parental engagement may contribute to obesity risk. Past evidence (Gortmaker et al., 1996; Robinson, 2005; Vandewater, Shim & Caplovitz, 2004) has demonstrated that excessive television viewing is related to obesity risk due to the sedentary nature of TV viewing and viewers’ vulnerability to unhealthy food marketing. In addition, parenting strategies that include family rules may be especially important as a protective factor against obesity status (Anderson & Whitaker, 2010; Hearst et al., 2012). Family rules reflect levels of limit-setting for managing children’s daily activities within a household. The existence of more rules within the family indicates that children may use higher levels of self-regulation in their daily activities (Carlson et al., 2010). Consequently, consistent rules in the home may mitigate impulsive over-consumption and promote regular physical activity (Fisher & Birch, 1999; Videon & Manning, 2003).

Similarly, parental control and parental engagement may also play vital roles in the risk for child obesity. Parental control can be measured by the amount of choice parents give children in setting limits on their daily activities and is a proxy for level of autonomy that children receive from their parents (Silk, Morris, Kanaya, & Steinberg, 2003; Spear & Kulbok, 2004). Parental engagement can be measured by the level of parents’ engagement in parent-child activities; a high level of parental engagement generally indicates a closer parent-child relationship (Bandy & Moore, 2008). Potentially, parental control may increase consumption of nutritious foods, help children to develop healthy habits, and, consequently, lower obesity risk. However, when adolescents are seeking more autonomy and spending less time at home, the effect of parental control on obesity becomes unclear, as past studies have shown both positive and negative relations between parental control and obesity risk (Rhee et al., 2006; Robinson, Kiernan, Matheson, & Haydel, 2001). In contrast to the positive relationship between parental control and obesity risk, such control could prevent children from developing personal responsibility for healthy consumption. This lack of responsibility may directly contribute to the risk of adolescent obesity as adolescents begin to purchase and consume products with less parental supervision. Thus, a better understanding of whether these aspects of family environment are related to adolescent obesity status is warranted.

This study aimed to examine developmental trajectories (initiation, persistence, and alternation) of obesity status from ages 10–18 and investigate whether and how prenatal and familial factors are associated with such trajectories. It was hypothesized that children with adverse prenatal exposures may be more susceptible to adolescent obesity. In contrast, the existence of family rules, parental control and engagement in their child’s activities, and limited hours of television viewing may mitigate the risk of adolescent obesity over time.

Method

Participants

The current study examined 5,156 American children from the child sample of the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79; U.S. Department of Labor, 2008). The original NLSY79 sample was selected using national representative probabilities of youth living in the United States in 1978, and consisted of 12,686 young men (N=6,403) and women (N=6,283) who were 14 to 21 years old when they were first surveyed in 1979. These youths were surveyed annually from 1979 to 1994 and biennially from 1996 to present. Starting in 1986, an additional child survey was initiated to administer a battery of assessments (e.g., height, weight, and cognitive, social, and psychological development) on all children born to female NLSY79 respondents, and to gather a variety of information related to family, school, jobs, peers, attitudes, and deviant behaviors from children when they were age 10 and older.

Data on children have been collected biennially since 1986. In 1986, 4,971 children were interviewed. Newborn children were added in each subsequent wave. By 2008, 11,495 children had participated. Due to the nature of the longitudinal study, children born in a young birth cohort (e.g., birth years from 1993 to 2008), compared to children born in an old birth cohort (e.g., birth years of 1992 or earlier), had fewer waves of interviews completed by 2008. To ensure that there were sufficient data on each child to estimate the trajectory of his/her obesity status from 10 to18 years, we examined the 5,156 children who had completed at least 8 waves of interviews during the biennial data collection from 1986 to 2008 and had provided information on the maternal health and family environment variables. This study sample was 50.0% female; the ethnicity breakdown of the sample was 41.7% White, 34.9% African American, 21.6% Latino, and 1.8% of other ethnicities.

Procedures

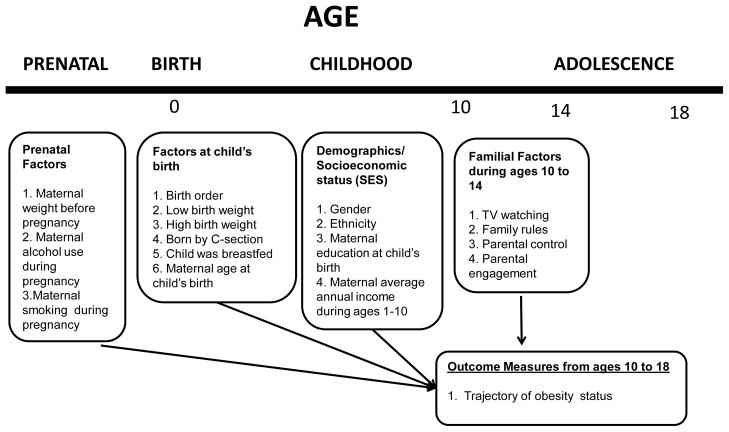

The child survey was administrated by interviewers who were trained to assess each child and to provide evaluations of each family’s home environment. Interviews with all children through 1993 were typically conducted in person using paper and pencil in the households of respondents. Starting in 1994, computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI), rather than the paper-and-pencil method, was used for interviews. Beginning in 2000, interviews of children aged 15 or older shifted to phone rather than in-person interviews. Informed consent was obtained from mothers and assent from children. In addition, a set of created variables drawn from the main NLSY79 survey that provided information on mothers with respect to their child’s life situation was also included. This constructed information included items on maternal health-risk behaviors during pregnancy with the child, mother’s status/practice (e.g., age, weight, education, breastfeeding) and child’s status (e.g., birth order and weight) at the child’s birth, and maternal work history before and after the child’s birth. The inclusion of comprehensive measures on both mothers and children over time provides a unique opportunity to investigate the conceptual model (Figure 1) of the study.

Figure 1.

Model of Longitudinal Association of Prenatal and Childhood Factors with Trajectory of Obesity Status from ages 10 to 18

Measures

The variables selected for the study were intended to represent the conceptual model presented in Figure 1. These measures chronologically indicated domains of factors and experiences related to the development of obesity status across children’s important developmental stages from the prenatal period, through childhood, and then to adolescence. Measures during the prenatal period and at the child’s birth consisted of mother-specific health-risk behaviors during pregnancy with the child, as well as children’s characteristics and maternal characteristics and health practices at the child’s birth. Measures in childhood (from ages 10 to 14) mainly concerned familial/environmental factors, including hours of TV viewing, and levels of family rules, parental control, and parental engagement. The outcomes were biennial measures of children’s obesity statuses from ages 10 to 18. Such chronologically arranged measures allowed for a comprehensive examination of longitudinal associations of prenatal exposures and familial experiences with developmental trajectories of obesity status from 10 to 18 years.

Prenatal measures

Mothers self-reported their weight before pregnancy with their children. Mother’s weight before pregnancy was categorized into 4 groups, including less than 125 pounds, 125–149 pounds, 150–174 pounds, and over 174 pounds. Also mothers reported whether they ever used alcohol and/or smoked cigarettes during their pregnancy with the child as well as frequency of alcohol use and quantity of cigarette smoking during pregnancy. In the analysis, maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy was indicated by number of cigarettes smoked per day during pregnancy. Responses were categorized as no smoking, less than one pack of cigarettes per day or one or more packs of cigarettes per day. Maternal alcohol drinking during pregnancy was represented by days of alcohol drinking per month during pregnancy, with four possible responses (no alcohol use, less than once per month, 1 to 4 days per month, and 5 or more days per month).

Birth weight and birth order of children

Child’s birth weight and birth order were recorded. Children who had a birth weight less than 2500 grams (or 5.5 pounds) were indicated as having a low birth weight (1=yes; 0=no) and those who had a birth weight greater than 4000 grams (or 8.8 pounds) were indicated as having a high birth weight (1=yes; 0=no). Children’s birth order was categorized as 1, 2, 3, and 4 (or after), indicating that the children were the first, second, third, or fourth (or subsequently) born.

Maternal age and health practices

Data were available regarding mother’s age at child’s birth, whether the child was born by Cesarean section (1=yes; 0=no), and whether the child was ever breastfed (1=yes; 0=no). Maternal age at child’s birth was classified into 4 groups, including less than 20 years, 20–24 years, 25–30 years, and 30+ years.

Mother’s education level at child’s birth

Mothers reported years of education received prior to the birth of the child. Years of education at child’s birth was sorted as less than high school (0–11 years), high school completion (12 years), and some college or more higher education (13 or more years).

Maternal work history

Maternal work history was collected regarding mothers’ quarterly (13-week period) employment activities and job characteristics starting 1 year prior to the child’s birth and continuing for 10 years after the child’s birth. Mothers’ total earnings from all jobs during the 13-week period were also reported. Mothers’ averaged annual income during the 10 years after the child’s birth was computed.

Childhood familial factors

In addition to demographic characteristics, measures of the family environment for children between the ages of 10 and 14 were obtained.

Gender and race/ethnicity

Females were coded as 1, and males were coded as 0. For race/ethnicity, two dummy variables were created: African American (1=yes; 0=no) and Latino (1=yes; 0=no).

Television viewing

Questions on amount of television viewing were posed to children aged 10 to 14 as well as their mothers. For children aged 3 or older, mothers reported the number of hours of television watching on a typical weekday as well as each weekend day. Children aged 10 and older also reported hours of television viewing on a typical weekday, typical Saturday, and typical Sunday. Averaged hours of television viewing on a typical weekday reported by mothers for children aged 10 to 14 were used for the analysis because mothers may be more capable of accurately reporting hours of television viewing, and measures of television viewing on a typical weekday and during weekends were highly correlated (r=0.77).

Family rules

Using questions adapted from the National Survey of Children, Wave 2 1980 (www.childtrends.org), children reported on the existence of family rules in the home. Children were asked whether there were any rules at home about watching television, parents knowing where you are, doing homework, or dating. Responses were given in a yes=1 or no=0 format. The number of rules in the home was used for the analysis.

Parental control

Using questions adapted from the National Survey of Children, Wave 2 1980 (www.childtrends.org), children reported on whether they had any control in implementation of family rules. Children were asked how much say they had in rules, compared to parents, about watching television, keeping parents informed, doing homework, and dating. Responses ranged from 1=no say at all to 4=a lot of say. The coding of responses were first reversed and then summed, with higher scores indicating greater parental control.

Parental engagement

A series of questions regarding engagement in parent-child activities was asked. Children reported whether they had gone to movies, to dinner, shopping, on an outing, and to church with parents in the past month. Responses were given in a yes=1 or no=0 format. The sum of the number of activities with parents in the past month was used.

BMI percentile and obesity status in adolescence

Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) is a measure of body weight adjusted for height and is the most commonly recommended and widely used measure for classifying adolescent and adults as overweight or obese (e.g., Barlow & The Expert Committee, 2007; Ogden et al., 2010). BMI was used to identify obesity status at each time point (biennially) from ages 10 to 18. Using BMI scores calculated with self-reported weight and height from ages 10 to 18, age- and gender-specific BMI percentiles were computed using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2000). At each time point, those having a BMI percentile at or above 95% were classified as meeting adolescent obesity. Repeated observations of obesity statuses from ages 10 to 18 were analyzed to estimate trajectory of obesity from ages 10 to 18.

Statistical Analyses

The hierarchical generalized linear modeling (HGLM) approach was applied to examine longitudinal impact of prenatal factors as well as childhood familial experiences on developmental trajectory of obesity status from ages 10 to 18. Hierarchical generalized linear modeling is a multilevel approach that processes longitudinal data as hierarchically structured data and nests repeated measures within an individual. This type of modeling has the advantage of properly accounting for intra-correlation among repeated measures over time. Hierarchical generalized linear models were developed using obesity status (BMI percentiles ≥ 95%) from ages 10 to 18 as the outcome. In this application, the level-1 model described the growth profiles for each individual using repeated observations of each outcome measure, and the level-2 model captured the potential influence of prenatal and childhood covariates on the variation of growth profiles among all children. Specifically, each child’s outcome trajectory over time was characterized by individual-varying intercept and slope (i.e., random intercept and random slope), which allowed for assessing whether intercepts (i.e., initial status) and slopes (i.e., changes over time) differed significantly among all children and whether the variations in the intercepts and the slopes might be due to prenatal and familial factors. Demographics and factors summarized in Figure 1 were included as level-2 covariates in the modeling. The binary outcome variable (e.g., obesity status) was generalized into a linear setting with logistic transformation on the binary variable. The hierarchical generalized linear models were developed using HLM software (version 6.2; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Results

Participants’ characteristics by obesity status (BMI percentile ≥ 95%) from ages 10 to 18

Of the 5,156 children, 1,371 met obesity status at least once across five biennial observations from ages 10 to 18. Table 1 summarizes comparisons of participants’ characteristics by obesity status. Males, in contrast to females, exhibited a higher prevalence of obesity from ages 10 to 18 years. African Americans exhibited higher obesity prevalence than Whites and Latinos. A higher maternal weight before pregnancy and maternal smoking during pregnancy were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of adolescent obesity. However, maternal alcohol use during pregnancy was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of adolescent obesity.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics by obesity status (BMI percentile ≥ 95%) from ages 10 to 18

| Normal BMI percentile < 95% (n = 3,781) | Obesity BMI percentile ≥ 95% (n = 1,371) | Total (n = 5,156) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | |||

| Gender, % ** | |||

| Males | 49.0 | 52.7 | 50.0 |

| Females | 51.0 | 47.3 | 50.0 |

| Ethnicity, % ** | |||

| Latino | 21.3 | 22.4 | 21.6 |

| African American | 32.5 | 41.6 | 34.9 |

| White | 44.4 | 34.2 | 41.7 |

| Other | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Prenatal Factors: | |||

| Mother’s weight just before pregnancy, % ** | |||

| Less than 124 pounds | 45.6 | 25.6 | 40.4 |

| 125–149 | 38.3 | 37.2 | 38.0 |

| 150–174 | 11.4 | 20.0 | 13.7 |

| 175+ | 4.6 | 17.3 | 7.9 |

| mean (SD) ** | 128.9 (23.5) | 145.6 (34.0) | 133.3 (27.7) |

| Mother drank alcohol during pregnancy, % ** | |||

| No alcohol use | 67.4 | 73.1 | 68.9 |

| Less than once a month | 15.9 | 13.1 | 15.1 |

| 1 to 4 days a month | 12.3 | 9.8 | 11.7 |

| 5 or more days a month | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.3 |

| Mother smoked cigarette during pregnancy,% * | |||

| Did not smoke | 73.7 | 69.8 | 72.7 |

| Less than 1 pack per day | 19.4 | 22.9 | 20.4 |

| 1 pack or more per day | 6.9 | 7.3 | 6.9 |

| Factors at and after birth of child: | |||

| Birth order of child, % | |||

| 1 | 48.1 | 45.1 | 47.3 |

| 2 | 32.6 | 33.0 | 32.7 |

| 3 | 13.5 | 15.0 | 13.9 |

| 4 or after | 5.8 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| Child had low birth weight (<2,500 g), % | 8.3 | 6.9 | 7.9 |

| Child had high birth weight (>4,000 g), % ** | 9.7 | 12.8 | 10.5 |

| Child delivered by C-section, % | 19.2 | 20.7 | 19.6 |

| Child was ever breastfed, % ** | 41.8 | 35.2 | 40.1 |

| Age of mother at birth of child, % | |||

| Less than 20 | 23.0 | 21.7 | 22.7 |

| 20–24 | 41.3 | 39.7 | 40.9 |

| 25–29 | 29.8 | 33.1 | 30.7 |

| 30–34 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.7 |

| Mother’s education at child’s birth, % ** | |||

| Less than high school | 33.8 | 38.6 | 35.1 |

| High school | 40.5 | 39.1 | 40.1 |

| College or higher | 25.7 | 22.3 | 24.8 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) ** | 11.8 (2.3) | 11.5 (2.2) | 11.7 (2.3) |

| Mother’s averaged annual earnings during 10 years after child’s birth, % | |||

| Less than 5,000 | 39.1 | 39.0 | 39.1 |

| 5,000–9,999 | 31.4 | 33.6 | 32.0 |

| 10,000–19,999 | 20.4 | 20.1 | 20.4 |

| 20,000 + | 9.1 | 7.4 | 8.5 |

| mean (SD) | 8,889 (10,407) | 8,427 (8,632) | 8,769 (9,967) |

| Childhood familial factors: | |||

| Hours of TV viewing on a typical weekday, % ** | |||

| 0–2 | 12.5 | 7.4 | 11.1 |

| 3–4 | 25.6 | 21.2 | 24.4 |

| 5–6 | 20.5 | 21.8 | 20.9 |

| 7–8 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.0 |

| 9+ | 28.5 | 36.2 | 30.6 |

| mean (SD) | 7.1 (5.5) | 8.2 (5.7) | 7.4 (5.6) |

| Family rules (0–4) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.7) |

| Parental control (4–16) | 10.4 (2.5) | 10.5 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.5) |

| Parental engagement (0–5) | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.2) |

Chi-square test:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

The children’s characteristics/experiences at birth were associated with obesity status in adolescence. Children who had a high birth weight exhibited a greater likelihood of obesity in adolescence. Children who were ever breastfed exhibited a lower likelihood of obesity in adolescence. Additionally, mothers’ educational levels at childbirth were associated with their children’s obesity status; children with mothers who had lower education at their births were more likely to meet obesity status in adolescence.

Hours of television watching from ages 10 to 14 was the most significant familial factor associated with prevalence of obesity status in adolescence. Children who watched television less than 2 hours and those who watched more than 9 hours of television on a typical weekday exhibited lower and higher prevalence of obesity in adolescence, respectively. Indices of family rules, parental control, and parental engagement did not significantly vary by adolescent obesity status in the bivariate comparisons.

The HGLM: Factors associated with trajectory of obesity status from ages 10 to 18

In addition to bivariate comparisons of prevalence of adolescent obesity, Table 2 presents the results of the HGLM, which assessed factors associated with trajectory of obesity status from ages 10 to 18. The trajectory of obesity risk decelerated from ages 10 to 18, with an estimated intercept of −2.23 at initial age of 10 accompanied with a decelerated rate of −0.06 across ages. Females, compared to males, exhibited a greater deceleration of obesity risk over time. In contrast to Whites, Latinos and African Americans exhibited higher intercepts (β0), indicating higher risk of obesity at the initial age of 10. Latinos, compared to Whites, exhibited a lower growth rate (β1) on obesity risk from ages 10 to 18.

Table 2.

The hierarchical generalized linear model for predicting trajectory of obesity status from ages 10 to 18

| Initial obesity risk, β0j (SE) | Odds Ratio of β0j | Growth in obesity risk, β1j (SE) | Odds Ratio of β1j | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.23 (0.05)** | 0.11 ** | −0.06 (0.01)** | 0.94 ** |

| Demographics: | ||||

| Gender, | ||||

| Females (vs. males) | −0.11 (0.10) | 0.90 | −0.04 (0.02)* | 0.96 |

| Ethnicity, | ||||

| Latino (vs. white/other) | 0.72 (0.13) ** | 2.06 ** | −0.07 (0.02)** | 0.93 ** |

| African American (vs. white/other) | 0.64 (0.12) ** | 1.89 ** | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.99 |

| Prenatal Factors: | ||||

| Mother’s weight just before pregnancy, | ||||

| Less than 124 pounds | ||||

| 125–149 pounds (vs. ≤ 124) | 0.58 (0.11) ** | 1.79 ** | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.99 |

| 150–174 pounds (vs. ≤ 124) | 1.09 (0.14) ** | 2.97 ** | 0.03 (0.03) | 1.03 |

| 175+ pounds (vs. ≤ 124) | 1.93 (0.17) ** | 6.90 ** | 0.04 (0.03) | 1.04 |

| Mother drank alcohol during pregnancy | ||||

| Less than once a month (vs. no) | −0.14 (0.14) | 0.87 | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.97 |

| 1 to 4 days a month (vs. no) | −0.32 (0.16) * | 0.72 * | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.97 |

| 5 or more days a month (vs. no) | −0.14 (0.24) | 0.87 | −0.04 (0.04) | 0.96 |

| Mother smoked cigarette during pregnancy | ||||

| Less than 1 pack per day (vs. no) | 0.33 (0.12) ** | 1.40 ** | 0.01 (0.02) | 1.01 |

| 1 pack or more per day (vs. no) | 0.36 (0.20) ** | 1.43 ** | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.98 |

| Factors at and after birth of child: | ||||

| Birth order of child, | ||||

| 2 (vs. 1) | −0.01 (0.11) | 0.99 | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.98 |

| 3 (vs. 1) | −0.14 (0.16) | 0.87 | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.99 |

| 4 or after (vs. 1) | −0.44 (0.22) * | 0.64 * | 0.04 (0.04) | 1.04 |

| Child had low birth weight (<2,500 g) | −0.42 (0.19) * | 0.66 * | 0.05 (0.03) | 1.06 |

| Child had high birth weight (>4,000 g) | 0.55 (0.15) ** | 1.73 ** | −0.05 (0.03) * | 0.95 * |

| Child delivered by C-section | −0.08 (0.12) | 0.93 | 0.03 (0.02) | 1.03 |

| Child was ever breastfed | −0.23 (0.11) * | 0.79 * | 0.03 (0.02) | 1.03 |

| Age of mother at birth of child, | ||||

| 20–24 (vs. ≤ 20) | 0.25 (0.14) | 1.28 | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.96 |

| 25–29 (vs. ≤ 20) | 0.51 (0.17) ** | 1.67 ** | −0.08 (0.03) * | 0.92 * |

| 30–34 (vs. ≤ 20) | 0.48 (0.27) | 1.61 | −0.11 (0.05) * | 0.89 * |

| Mother’s education at child’s birth, | ||||

| Less than high school (vs. College +) | 0.45 (0.16) ** | 1.57 ** | −0.05 (0.03) | 0.95 |

| High school (vs. College +) | 0.29 (0.13) * | 1.33 * | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.96 |

| Mother’s averaged annual earnings during 10 years after child’s birth, | ||||

| 5,000–9,999 (vs. ≤ 5,000) | 0.23 (0.11) * | 1.26 * | −0.05 (0.02) * | 0.95 * |

| 10,000–19,999 (vs. ≤ 5,000) | 0.27 (0.14) | 1.31 | −0.06 (0.03) * | 0.94 * |

| 20,000 + (vs. ≤ 5,000) | 0.18 (0.20) | 1.20 | −0.10 (0.04) ** | 0.90 ** |

| Childhood familial factors: | ||||

| Hours of TV viewing on a typical weekday, | ||||

| 3–4 (vs. 0–2) | 0.37 (0.16) * | 1.45 * | 0.001 (0.03) | 1.00 |

| 5–6 (vs. 0–2) | 0.52 (0.18) ** | 1.68 ** | 0.02 (0.03) | 1.02 |

| 7–8 (vs. 0–2) | 0.55 (0.21) ** | 1.74 ** | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.99 |

| 9+ (vs. 0–2) | 0.56 (0.16) ** | 1.75 ** | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.97 |

| Family rules (0–4) | −0.16 (0.07) * | 0.85 * | 0.02 (0.01) | 1.02 |

| Parental control (4–16) | 0.02 (0.02) | 1.02 | −0.002 (0.003) | 1.00 |

| Parental engagement (0–5) | 0.07 (0.04) | 1.07 | −0.02 (0.01) * | 0.98 * |

| Estimated variance component for random coefficient | 2.91 | 0.001 | ||

Chi-square test:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Of the prenatal factors, maternal weight before pregnancy was significantly associated with initial obesity risk. As maternal weight increased, so did initial obesity risk of children at age 10. However, maternal weight before pregnancy was not associated with change of obesity risk (β1) from 10 to 18 years. Maternal alcohol drinking during pregnancy was associated with lower initial obesity risk of children at age 10; children whose mothers drank alcohol 1 to 4 days per month during pregnancy, in contrast to children whose mothers did not drink alcohol during pregnancy, exhibited a lower risk of obesity with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.72. Also, children exposed to prenatal maternal smoking exhibited higher initial obesity risk at age 10; the OR is 1.40 for mothers who smoked less than one pack of cigarettes per day and 1.43 for mothers who smoked one or more packs of cigarettes per day. However, both maternal alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking were not associated with change in obesity risk over time.

Regarding factors at or after the child’s birth, children who were 4th or higher in birth order, compared to first-birth-order children exhibited a lower initial obesity risk. Children who had a low birth weight (<2,500 grams) had a lower initial obesity risk. Conversely, high birth-weight children (>4,000 grams) had a higher initial obesity risk, but were less likely to have increased obesity risk over time. Also, children who were breastfed as infants exhibited a lower obesity risk at the initial age of 10. Relative to children born to younger mothers (≤ 20 years), children born to older mothers (25–29 years) exhibited a higher risk of obesity at age 10, but children born to older mothers were less likely to have an increased obesity risk during adolescence. The OR is 0.92 for maternal ages of 25–29 and 0.89 for maternal ages of 30–34.

In terms of socioeconomic variables, maternal education was negatively associated with children’s obesity risk. Compared to children whose mothers had more than a high school education, children whose mothers had a high school education or less than a high school education exhibited a higher obesity risk at the initial age of 10. Furthermore, maternal annual income was linearly correlated with slope of obesity risk over time; children living with higher-income mothers exhibited a greater deceleration on obesity risk over time. The OR is 0.95, 0.94 and 0.90 for income of 5–9k, 10–19k, and 20k+, respectively.

In terms of indices of familial experiences, hours of television viewing in a typical weekday were linearly associated with initial obesity risk; an increase in hours of television viewing was associated with an increase of initial obesity risk. However, the association between hours of television viewing and change of obesity risk from ages 10 to 18 was less salient. Additionally, existence of family rules was associated with lower obesity risk at initial age of 10, but it was not associated with change of obesity risk across ages. Higher level of parental engagement was associated with a greater deceleration on obesity risk during adolescence.

Discussion

There is an increasing body of evidence showing that multiple aspects of a child’s environment are important determinants of their risk for obesity (Gillman et al., 2008; Taveras, Gillman, Kleinman, Rich-Edwards, & Rifas-Shiman, 2010). This study has advantages over previous ones by applying a longitudinal design together with a multivariate modeling approach to examine potential determinants of adolescent obesity. The study identified prenatal and childhood factors that were related to the development of adolescent obesity, and provided empirical evidence demonstrating how such determinants of obesity operate at different life stages and yield different magnitudes of influence on obesity status in adolescence. The mechanism and duration of the influence on adolescent obesity vary among these factors. Prenatal factors and child’s birth statuses, including higher maternal weight before pregnancy, maternal smoking during pregnancy, less maternal education at child’s birth, and lack of infant breastfeeding, were associated with an elevated risk of obesity in early adolescence, but the impact of these contributors on the changes of obesity risk across the adolescent years was less salient, suggesting that prenatal and child-birth factors may have a relatively shorter duration of impact on obesity risk in adolescence. In contrast, maternal age at child’s birth, high birth weight of children, and maternal annual income were associated with initial risk of obesity at the beginning of adolescence and were also significantly associated with the changes of obesity risk across the adolescent years, indicating that these factors may have a more profound and long-lasting impact on developmental pathways of adolescent obesity. Similarly, in terms of contextual indicators of familial environment, the associations of obesity risk with television viewing and lack of family rules were more prominent in early adolescence at age10, but parental engagement was more associated with the changes of obesity risk across the adolescent years. In summary, these findings reveal that the impact of these contributors is a function of the age of the child, and their impact varies as the child ages. The findings also highlight the importance of considering the moderating influence of these factors across a child’s ages, particularly throughout the significant transitional period from childhood to adolescence.

Of the studied prenatal factors, higher maternal weight and higher level of maternal smoking during pregnancy were both associated with higher risk of adolescent obesity, which are consistent with prior research (Francis et al., 2007; Mamun et al., 2005; Oken et al., 2008; Reilly et al., 2005). A possible explanation for the association between level of prenatal smoking exposure and adolescent obesity is that smoking mothers are less likely to engage in other health-promoting behaviors (e.g., physical activity, eating nutritious meals, sleeping sufficiently), which may impede an adolescent’s opportunity and motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviors into adulthood (Johnson, Wang, Smith, & Connolly, 1996; Tilson, McBride, Albright, & Sargent, 2002). Our additional analyses also showed that children with prenatal smoking exposure were more likely to be exposed to other risk factors for heightened risk of adolescent obesity, including lower maternal education, lower likelihood of breastfeeding, and low income.

Our findings showed that the associations between maternal alcohol drinking during pregnancy and child obesity are differentiated by frequency of drinking. In contrast to children whose mothers did not use alcohol during pregnancy, children with mothers who used alcohol l–4 days per month during pregnancy exhibited a lower risk of adolescent obesity, but children with mothers who used alcohol less than once per month or who used alcohol 5 or more days per month exhibited no difference on obesity risk. This finding is contradictory to our hypothesis, as children who are exposed to a higher level of prenatal maternal alcohol use generally are at greater risk for poor physical health and behavioral problems (Christoffersen & Soothill, 2003; Chen, 2012). However, one caveat is that the quantity of alcohol consumption (one drink vs. binge drinking) per occasion during pregnancy is not available in the current study. This limitation may result in the contradictory finding and needs to be accounted for in future work. Our additional analyses found that mothers in the current study sample who consumed alcohol during pregnancy were more likely to breastfeed their children. Breastfeeding mothers may be more attentive to their children’s nutrition and health care, which may contribute to lower later obesity risk (CDC, 2007; Owen et al., 2005). Additional research to address potential underlying processes of the associations is warranted.

Furthermore, high birth weight (>4,000 grams), maternal age at child’s birth, and maternal annual income had a stable and long-term association with development of adolescent obesity; their effects on obesity risk lasted throughout adolescence (ages 10 to 18). In contrast to children with normal or low birth weight, children with a high birth weight exhibited higher obesity risk at the initial year of adolescence (age 10), but had a greater decrease of obesity risk across the years in adolescence. This suggests that although children with a high birth weight display higher BMI (or obesity risk) in childhood, a majority will have a slower rate of weight growth during adolescence, which may potentially lead to a non-obesity status. Similarly, children born to older mothers exhibited higher obesity risk at age 10, but a greater decrease on obesity risk over time. It is likely that older mothers, compared to younger mothers, may have had more experience in providing appropriate care to their children, which would diminish the adverse effect of the high maternal age at a child’s birth. Furthermore, an increase of maternal annual income was accompanied with a greater decrease in children’s obesity risk across the ages of 10 to 18. Working mothers with a higher income may be able to afford better health care and more healthy daily food for their children, which could lead to a lower obesity risk for adolescents. As for maternal education, it was only associated with obesity risk at the initial year of adolescence (age 10) but was not associated with the changes of obesity risk from ages 10 to18. The findings indicate that maternal education may have a short-term effect on children’s obesity risk in early adolescence, but the contribution of such an effect weakens when other factors, such as familial circumstances during adolescence, become more dominant later.

Moreover, this study demonstrates a significant association between childhood familial experiences and adolescent obesity. Consistent with prior findings, adolescent obesity risk linearly increased with hours of television viewing per day (Gortmaker et al., 1996), whereas the existence of family rules lowered adolescent obesity risk. Consistent with our expectation, parental engagement in parent-child activities accounted for a decrease in adolescent obesity risk across years. A probable explanation for these findings is that the implementation of family rules maintains consistency in the home, which may enhance development of self-regulation skills in children (Hearst et al., 2012). Parental engagement may enhance tight family connections. Children living in this type of family environment will be more willing to follow healthy food consumption advice and to sustain regular physical activity (Lindsay, Sussner, Kim & Gortmaker, 2006; Ornelas, Perreira & Ayala, 2007). However, the hypothesized association between parental control and adolescent obesity was not as well supported. It is likely that parental control over eating habits is linked to obesity status, as previously reported (Golan & Crow, 2004; Robinson et al., 2001), but the global indicator of parental control used in this study was not specific enough to ascertain these associations. Further study with specific measures assessing parental control on eating habits/diet and levels of physical activity may be helpful to better gauge the association between obesity and parental control.

The limitations of the findings should be noted. Self-report, as opposed to measured BMI, was used for analyses in this study. However, only minor differences in reliability between self-reported and measured BMI have been found in studies of adolescents (Field, Aneja, & Rosner, 2007; Sherry, Jefferds, & Grummer-Strawn, 2007). Second, questions in the NLSY79 child survey about family rules, parental control, and parental engagement did not include questions about eating habits; consequently, a direct association between eating habits and parental control on these habits was not examined. This may potentially explain why relations between measurement of parental control and adolescent obesity were not robust. Future work should seek to integrate aspects of eating and physical activity within family environment indicators. Furthermore, the effect of child’s status at birth (e.g., birth weight, maternal age) on adolescent obesity may be differentiated by the childhood familial environment. Our preliminary analyses indicated that the interactions of maternal age with three parenting measures (i.e., family rules, parental control, and parental engagement) were not significant in the HGLM analysis. However, the interaction of low birth weight with parental control was significant, indicating that parental control would lower obesity risk throughout adolescence for low birth-weight children. The findings suggest that examination of the interplay of child’s status at birth with childhood familial environment and their integrated effects on adolescent obesity constitute important areas that warrant additional studies. Lastly, children who exhibit obesity status at early adolescence (i.e., at age 10) may represent the most vulnerable subgroup. Future studies that specifically focus on this subgroup may help to advance our understanding of specific risk factors and possible mechanisms in obesity development among these vulnerable adolescents.

Despite these limitations, application of the study’s findings may enhance current obesity prevention and intervention efforts. Maternal smoking is strongly predictive of adolescent obesity. This information can be incorporated into existing smoking cessation interventions to inform mothers of potential negative consequences of smoking on their children’s physical health, in addition to already well-known health conditions (e.g., asthma). Furthermore, lack of family rules and parental engagement are related to adolescent obesity, suggesting some use of rules in the home together with parental involvement and support may buffer vulnerability to adolescent obesity. Parenting interventions targeting reductions in childhood obesity should highlight the potential utility of implementing rules at home as well as the importance of parental awareness and involvement in children’s daily activities. In sum, this longitudinal study reveals that certain prenatal exposures and childhood familial experiences are strongly tied to a developmental trajectory of adolescent obesity. In addition to children, their parents, particularly their mothers, should be an important target group of current prevention/intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by Grant Number R03HD064619 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and partially supported by the University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Advancing Longitudinal Drug Abuse Research (CALDAR) under Grant P30DA016383 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the University of California, Los Angeles, Drug Abuse Research Training Center sponsored by NIDA (5T32DA007272-19). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson SC, Whitaker RC. Household routines and obesity in US preschool-ages children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:420–428. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandy T, Moore KA. The parent-child relationship: A family strength. Child Trends, Publication #2008-27. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org.

- Barlow SE The Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendation regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Lee SM, Foley JT, Heitzler C, Huhman M. Influence of limit-setting and participation in physical activity on youth screen time. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e89–e96. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of pediatric overweight? Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity: Research to Practice Series No 4. 2007:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH. Maternal alcohol use during pregnancy, birth weight and early behavioral outcomes. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47:649–656. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen MN, Soothill K. The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: A cohort study of children in Denmark. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. The epidemiology of overweight and related lifestyle behaviors. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:S178–S186. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Aneja P, Rosner B. The validity of self-reported weight change among adolescents and young adults. Obesity. 2007;15:2357–2364. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to palatable foods affects children’s behavioral response, food selection, and intake. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;69:1264–1272. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LA, Ventura AK, Marini M, Birch LL. Parent overweight predicts daughters’ increase in BMI and disinhibited overeating from 5 to 13 years. Obesity Research. 2007;15:1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Ogden CL, Dietz WH. Racial and ethnic differences in secular trends for childhood BMI, weight, and height. Obesity. 2006;14:301– 308. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Oken E, Rich-Edwards JW, Taveras EM. Developmental origins of childhood overweight: Potential public health impact. Obesity. 2008;16:1651–1656. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Crow S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: Long term results. Obesity Research. 2004;12:357–361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:356–362. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst MO, Sevcik S, Fulkerson JA, Pasch KE, Harnack LJ, Lytle LA. Stressed out and overcommitted! The relationships between time demands and family rules and parents’ and their child’s weight status. Health Education & Behavior. 2012;39:446–454. doi: 10.1177/1090198111426453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Locke Wellman J, Rickin E, Lowers L. Offspring from families at high risk for alcohol dependence: Increased body mass index in association with prenatal exposure to cigarettes but not alcohol. Psychiatry Research. 2005;135:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RK, Wang M, Smith MJ, Connolly G. The association between parental smoking and the diet quality of low-income children. Pediatrics. 1996;97:312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC Growth Charts: United States advance data from vital and health statistics. No. 314. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. The Future of Children. 2006;16:169–186. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun AA, Lawlor DA, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM, Najman JM. Family and early life factors associated with changes in overweight status between ages 5 and 14 years: Findings from the Mater University Study of Pregnancy and its outcomes. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders. 2005;29:475– 482. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy A, Hughes R, Tilling K, Davies D, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y. Birth weight; postnatal, infant, and childhood growth; and obesity in young adulthood: Evidence from the Barry Caerphilly Growth Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;86:907– 913. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea JA, Caputi P. Association between socioeconomic status, weight, age and gender, and the body image and weight control practices of 6- to 19-year-old children and adolescents. Health Education Research. 2001;16:521–532. doi: 10.1093/her/16.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Levitan EB, Gillman MW. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:201–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM, Ayala GX. Parental influences on adolescent physical activity: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG. Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: A quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1367–1377. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons RK, Sevdy TL, Nichols WN. Does birth weight predict childhood obesity? Journal of Family Practice. 2008;57:409–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Jefferis BJ. Fetal environment and subsequent obesity: A study of maternal smoking. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:420–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear modes: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Ness A, Rogers I, et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: Cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:1357–1363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38470.670903.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee KE, Lumeng JC, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Bradley RH. Parenting style and overweight status in first grade. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2047–2054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Medical Association. 2005;282:1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TN, Kiernan M, Matheson DM, Haydel KF. Is parental control over children’s eating associated with childhood obesity? Results from a population-based sample of third graders. Obesity Research. 2001;9:306–312. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry B, Jefferds ME, Grummer-Strawn LM. Accuracy of adolescent self-report of height and weight in assessing overweight status: A literature review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:1154–1161. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Morris AS, Kanaya T, Steinberg L. Psychological control and autonomy granting: Opposite endings of a continuum or distinct constructs. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Spear JJ, Kulbok P. Autonomy and adolescence: A concept analysis. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.021208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss RS, Knight J. Influence of the home environment on the development of obesity in children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e85–e92. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125:686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilson EC, McBride CM, Albright JB, Sargent JD. Smoking, exercise and dietary behaviors among mothers of elementary school-ages children in a rural North Carolina county. Journal of Rural Health. 2002;18:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. The NLSY79 Children and Young Adults. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2008. National Longitudinal Surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater EA, Shim M, Caplovitz AG. Linking obesity and activity level with children’s television and video game use. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM, Manning CK. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: The importance of family meals. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32:365–373. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00711-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Q. Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:707–716. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC. Predicting preschooler obesity at birth: The role of maternal obesity in early pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e29–e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]