Introduction

About half of the women attending the NHS breast screening programme have used hormone replacement therapy.1 Although previous studies have reported that use of hormone replacement therapy increases the risk of being recalled after mammography for further assessment, with no subsequent diagnosis of breast cancer (“false positive recall”), the effect of different patterns of use is unclear.2

Participants, methods, and results

From June 1996 to March 1998, 87 967 postmenopausal women aged 50-64 invited to routine breast cancer screening at 10 NHS breast screening programme centres joined the million women study,3 by completing a self administered questionnaire before screening, and were followed up through records from screening centres for their screening outcome. Overall, a diagnosis of breast cancer was made in 399 (0.5%) and 2629 (3.0%) had false positive recall (recall to assessment with no diagnosis of breast cancer during that screening episode). Among women with false positive recall, 398 (15.1%) had a negative biopsy (fine needle aspiration cytology, wide bore needle biopsy, or open surgical biopsy, with no diagnosis of breast cancer). We used conditional logistic regression, stratified by the factors listed in the figure, to calculate the relative risk of false positive recall.

Figure 1.

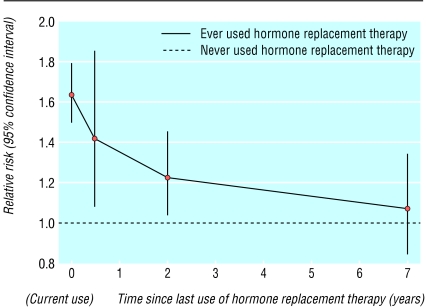

Relative risk of false positive recall in postmenopausal women in relation to time since last use of hormone replacement therapy. (Relative risk compared with never users (1057/44 427 recalled) stratified by screening centre, age, previous screening, body mass index, previous breast operation, and time since menopause in: current users of hormone replacement therapy (relative risk 1.64, 95% confidence interval 1.50 to 1.80; 1157/28 634 recalled); past users ceasing use <1 year ago (1.42, 1.08 to 1.86; 63/1758 recalled), 1-4 years ago (1.23, 1.04 to 1.46; 176/5910 recalled), and ≥ 5 years ago (1.07, 0.85 to 1.34; 92/3800 recalled)). Results are plotted according to the median number of years since last use of hormone replacement therapy in each of these categories

False positive recall was significantly increased in current users of hormone replacement therapy (relative risk 1.64, 95% confidence interval 1.50 to 1.80, P < 0.0001) and past users (1.21, 1.06 to 1.38, P = 0.004), compared with never users. The relative risk of false positive recall decreased significantly with increasing time since last use of hormone replacement therapy (χ2 (df = 1) for trend = 14.0, P < 0.0001), and was still significantly raised among women ceasing use within the past five years (figure). We found no significant variation in the relative risk of false positive recall between current users of oestrogen only (1.62, 1.43 to 1.83) and combined oestrogen and progestogen (1.80, 1.62 to 2.00) (χ2 (df = 1) for heterogeneity = 2.3, P = 0.1), nor were there significant differences in risk according to the dose or hormonal constituents of these types of hormone replacement therapy. Current, but not past, users of hormone replacement therapy had a significantly increased risk of having a negative biopsy compared with never users (relative risk 1.42, 1.14 to 1.78, and 0.94, 0.69 to 1.30, respectively (χ2 (df = 1) for heterogeneity = 6.5, P = 0.01)).

When these relative risks and the prevalences of use of hormone replacement therapy in the million women study1 are applied to recall rates in the NHS breast screening programme,4 use of hormone replacement therapy during the study period is estimated to have been responsible for around 20% of the cases of false positive recall in the NHS breast screening programme, amounting to an excess of 14 000 cases per year.

Comment

The risk of false positive recall is significantly and substantially increased in current and recent users of hormone replacement therapy; this effect persists for several years after use ceases and, in current users, is accompanied by an increased risk of having a biopsy performed.

False positive mammography is important, because of the anxiety, extra investigations, and inconvenience recalled women experience and its resource implications.2 Moreover, recalled women are less likely to accept subsequent invitations for screening, despite having a higher incidence of breast cancer than women who have not been recalled.5 An increased risk of false positive recall can be justified if it improves cancer detection, but current use of hormone replacement therapy reduces the ability of mammographic screening to detect breast cancer,2 such that the increase in false positive recall is not offset by improved cancer detection.

Our finding that the effect of hormone replacement therapy takes several years to wear off does not support suggestions that the high rates of false positive recall in current users could be largely reversed if women ceased use of hormones weeks or months before mammography.

We thank the many women who completed questionnaires for this study. We are grateful to the staff at the collaborating breast screening units and at the Million Women Study coordinating centre for their valuable contribution to the study and to Adrian Goodill for producing the figure.

Contributors: Emily Banks, Gillian Reeves, Valerie Beral, and Julietta Patnick had the original idea for the study, with important input on practical aspects of study design from Barbara Crossley, Elizabeth Hilton, and Moya Simmonds. Diana Bull analysed the data; Emily Banks, Gillian Reeves, Valerie Beral, Julietta Patnick, and Matthew Wallis interpreted the data. Stephen Bailey, Nigel Barrett, Peter Briers, Ruth English, Alan Jackson, Elizabeth Kutt, Janet Lavelle, Linda Rockall, Matthew Wallis, and Mary Wilson contributed to local study design and conduct. All of the authors participated in drafting the paper and gave final approval of the version to be published. Emily Banks, Gillian Reeves, and Valerie Beral are guarantors.

Funding: The Million Women Study is supported by Cancer Research UK, the Medical Research Council, and the NHS Breast Screening Programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Anglia and Oxford Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Million Women Study Collaborators. Patterns of use of hormone replacement therapy in one million women in Britain, 1996-2000. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109: 1319-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks E. Hormone replacement therapy and the sensitivity and specificity of breast cancer screening: a review. J Med Screen 2001;8: 29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Million Women Study Collaborative Group. The million women study: design and characteristics of the study population. Breast Cancer Res 1999;1: 73-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patnick J. 2002 NHS breast screening programme review. Sheffield, UK: NHS Breast Screening Programme, 2002.

- 5.McCann J, Stockton D, Godward S. Impact of false positive mammography on subsequent screening attendance and risk of cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2002;4: R11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]