Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the tolerability and toxicity of PCI in patients with NSCLC.

Background

Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is a standard treatment for patients with small cell lung cancer. There are data showing a decreasing ratio of brain metastases after PCI for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC-non small cell lung cancer) patients but, so far, there is no evidence for increasing overall survival. The main concern in this setting is the tolerance and toxicity of the treatment.

Materials and methods

From 1999 to 2007, 50 patients with NSCLC treated with radical intent underwent PCI (30 Gy in 15 fractions). Mean follow-up was 2.8 years. The tolerability and hematological toxicity were evaluated in all patients, a part of participants had done neuropsychological tests, magnetic resonance imaging with 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, and estimation of pituitary function.

Results

During follow-up, 20 patients developed distant metastases, 4-brain metastases. Fourteen (30%) patients had acute side effects: (headache, nausea, erythema of the skin). The symptoms did not require treatment breaks. Six patients complained of late side effects (vertigo, nausea, anxiety, lower extremity weakness, deterioration of hearing and olfactory hyperesthesia). Hematological complications were not observed. Testosterone levels tended to decrease (p = 0.062). Visual-motor function deteriorated after treatment (p < 0.059). Performance IQ decreased (p < 0.025) and the difference between performance IQ and verbal IQ increased (p < 0.011). Degenerative periventricular vascular changes were observed in two patients. Analysis of the spectroscopic data showed metabolic but reversible alterations after PCI.

Conclusion

PCI in the current series was well tolerated and associated with a relatively low toxicity.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI), Toxicity of radiotherapy, Testosterone level, MRS – 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra

1. Background

The high incidence of brain metastases in patients with lung cancer has led to an increased interest in prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI). PCI is now a standard treatment for patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). It decreases the incidence of brain metastases (BM) and increases the 3-year survival rate from 15% to 21% in limited-disease SCLC and from 13% to 27% at 1 year in extensive-disease SCLC.1,2 After treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), BM develop in 18–54% of patients,3–5 and may develop as the first sign of dissemination in 15–40% of patients.3,4 The risk of BM is particularly high after surgery and in long term survivors.6,7

Most studies on PCI in NSCLC report a decrease in the incidence of BM without an effect on overall survival.3–5,8–10,6 After PCI, BM are reported in 4–9% of patients.5,8,10,11 The phase III RTOG 0214 study5 published in 2011 comparing PCI versus observation in patients with advanced NSCLC demonstrated a reduced probability of BM by a factor of 2.52. Many patients and physicians consider the decrease in the incidence of BM to be a sufficient reason for PCI because of the devastating influence of CNS involvement on the patient's and family's quality of life, but a widespread use of PCI is withheld mainly due to concerns about the toxicity of the treatment.

2. Aim

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the tolerability and toxicity of PCI in patients with NSCLC treated with standard therapy.

3. Materials and methods

From 1999 to 2007, 50 patients with NSCLC treated at MCS Memorial Institute of Oncology in Gliwice with definitive therapy were asked to undergo PCI during the final phase of standard treatment. The group was not homogeneous and comprised both patients who had undergone surgery and patients who had undergone definitive radiotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy.

All the patients participating in the study fulfilled the inclusion criteria: histologically proven NSCLC, definitive treatment, ECOG performance status 0–2, age 18–75 years, white blood cell count of at least 4 × 103, platelet count of at least 150 × 103, no history of other malignant tumors, and informed consent provided. Exclusion criteria included distant metastases, diseases potentially impairing CNS tolerance for radiotherapy (uncontrolled diabetes, demyelinating disease, paraneoplastic symptoms, and generalized atherosclerosis). The study was approved by the institutional review board and conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The sixth edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) tumor-node-metastases classification was used for staging. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 50 |

| Men/women | 41/9 |

| Age range (years)/mean age | 38–73/56 |

| Staging (6th UICC) | |

| Tx/T1/T2/T3/T4 | 1/1/32/6/10 |

| Nx/N1/N2/N3 | 1/11/36/2 |

| Clinical stage: undetermined/II B/III A/III B | 1/6/29/14 |

| Histology | |

| NSCLC (NOS) | 3 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 14 |

| Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | 3 |

| Definitive surgery | |

| Yes/no | 4/46 |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes/no | 37/13 |

| Chemotherapy protocol | |

| Cisplatin + Vinorelbin | 30 |

| Cisplatin + Etoposide | 4 |

| Cisplatin + Gemcitabine | 3 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | |

| Range (mean) | 1–6 (mean 2.4) |

| 1–2 | 8 |

| 3–4 | 24 |

| 5–6 | 4 |

| Type of treatment | |

| Surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy ± radiotherapy | 3 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy + surgery + radiotherapy | 1 |

| Radical radiotherapy | 13 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 33 |

| Radiotherapy dose | |

| Mean (range) | 66 (44–72) Gy |

NSCLC – non-small cell lung cancer, NOS – not otherwise specified.

PCI was defined as whole brain radiotherapy to total dose of 30 Gy in 15 fractions, given daily 5 times per week, during the last 3 weeks of radiotherapy or at least 2 weeks after the end of adjuvant chemotherapy (in patients not treated with radiotherapy). The minimum interval between chemotherapy and PCI was 2 weeks. Three-dimensional computed tomography-based radiotherapy planning was used in all cases and treatment was delivered by 6 and/or 20 MV photons. Patients were immobilized with thermoplastic masks.

Any complaints related to PCI during and after treatment were recorded, as well as events of alopecia and time to hair regrowth.

A full blood count was performed before and immediately after PCI in all patients.

Steroids were used at the discretion of the physician.

Pituitary function was estimated by measuring serum testosterone levels before and immediately after PCI, and during follow-up in 10 male patients.

Neuropsychological tests: the Benton Visual Retention Test (method A, BVRT) and Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test (BVMGT) – scored using the Pascal-Suttell method were performed before and immediately after PCI (n = 32) and 6 months after PCI (n = 10). The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) test was performed before (n = 32) and 6 months after the treatment (n = 10).

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed: before PCI (exam 1), up to 1 month after PCI (exam 2), and 3 months after PCI (exam 3) in 10 patients. All magnetic resonance images were reviewed by one radiologist (ŁZ). In patients who underwent MRI, forty-four in vivo 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (MRS) were acquired (in the same scheme) with the whole-body MRI/MRS 2T system operating at the proton resonance frequency of 81.3 MHz (during MRI examination). For each patient, volumes of interest of 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm were located in the left frontal and occipital normal-appearing white matter (NAWM). The absolute concentrations of the main brain metabolites: N-acetylaspartate (NAA), choline (Cho), myoinositol (mI), total creatine (tCr), glucose (Glc), glutamine and glutamate (Glx), lactate (Lac), and lipids (Lip) were calculated as previously described.12 To compare the obtained results with data from the available literature, the metabolite concentrations were additionally presented as the following ratios: NAA/tCr, Cho/tCr, Cho/NAA, mI/tCr, Lac/NAA, Lip/NAA, Glc/tCr, Glx/tCr, Lac/tCr, Lip/tCr.

Mean follow-up was 2.8 years (calculated from the last treatment day).

Statistics: Overall survival was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier test.

The Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were applied for statistical analysis of neuropsychologic tests and clinical data.

For evaluation of the spectroscopic data, the absolute metabolite concentrations and metabolite ratios were paired according to the examination schedule and subjected to the Wilcoxon matched pair test: exam 1 vs. exam 2, exam 1 vs. exam 3, and exam 2 vs. exam 3. Analyzes were performed separately for frontal and occipital volumes of interest. The correlations between the absolute metabolite ratios were tested with Pearson product-moment method.

4. Results

Median overall survival was 1.8 years (range 0.15–5.1). The 3-year survival rate was 32%.

Twelve (40%) patients developed distant metastases, 4 (8%) had BM. In three patients (6%), BM appeared during the first 2 years of follow-up, two patients had isolated BM, and one had local recurrence simultaneously with BM. In the fourth patient, cerebral involvement was simultaneous with bone metastases and was diagnosed 4.8 years after treatment.

Determination of quality of life (QoL) in all patients based on RTOG questionnaires was impossible due to logistical reasons and thus, it was not included in the study protocol. Instead, we asked patients to report the complaints during PCI and on follow-up visits. They were also asked how their well-being had changed after PCI.

During PCI, 14 (30%) patients had acute side effects: 10 headache, 2 nausea, and 2 erythema of the irradiated skin. All of the symptoms were easily treated and did not cause any breaks or cessation of the treatment.

After PCI, 6 (13%) patients complained of late side effects (one or two of the following): 3 for vertigo, 1 for nausea, 2 for anxiety, 1 for deterioration of hearing and olfactory hyperesthesia, and 1 for lower extremity weakness.

All patients developed alopecia after PCI. In all but one patient, hair regrowth was observed between 1.5 and 6 months after PCI (median 2.5 months).

There was no significant change in blood count at the completion of PCI. White blood cell counts tended to increase at the end of PCI. Conversely, platelet counts tended to decrease but without statistical significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean value of hemoglobin, white blood cell and platelet before and after PCI.

| Mean value of | Hemoglobin (g/dl) | White blood cells × 103 | Platelet × 103 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before PCI | 12.8 | 8.2 | 275 |

| After PCI | 12.9 | 11.5 | 264 |

| p value | 0.6 | 0.21 | 0.5 |

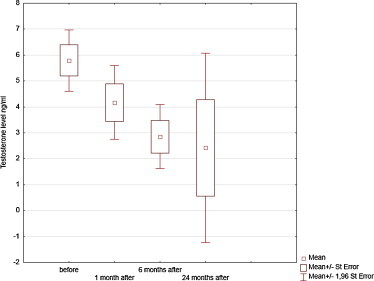

Serum testosterone levels declined during treatment and during the first months after treatment, but still the difference did not reach statistical significance (Wilcoxon test p = 0.062) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Testosterone serum level before and after treatment.

In neuropsychological tests intelligence and visual memory (assessed in WAIS-R and BVRT) did not change between subsequent examinations (before and after PCI). Before brain irradiation 13% of patients demonstrated visual memory impairment (adjusted to age and IQ). After the treatment the percentage decreased to 9%, but the difference was not statistically significant. The statistical difference was found in visual-motor function (assessed in Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Test) that deteriorated immediately after treatment (Wilcoxon test p < 0.05), but after 6 months the difference was no longer statistically significant. Performance IQ slightly but significantly decreased by 5 points 6 months after PCI (p < 0.02). Similarly, the difference between performance IQ and verbal IQ increased 6 months after treatment (p < 0.011), which could suggest a slight psychoorganic cognitive deterioration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of neuropsychological tests.

| Variable | Before PCI (32 pts) | After PCI (32 pts) | 6 months after PCI (10 pts) | p – Friedman Anova |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ (WAIS-R) Mean points (SD) |

97.1 (SD = 16.5) | – | 94.9 (SD = 22.5) | p = 0.31 |

| Verbal IQ (VIQ) Mean points (SD) |

100.53 (SD = 14.8) | – | 101.2 (SD = 20) | p = 0.09 |

| Performance IQ (PIQ) Mean points (SD) |

95.4 (SD = 14.6) | – | 90.6 (SD = 18.4) | p = 0.02 |

| Difference between PIQ and VIQ (Δ) Mean points (SD) |

3.9 (SD = 12.4) | – | 10.6 (SD = 12.4) | p = 0.011 |

| Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) Mean number of correct answers (SD) |

6.4 (SD = 2) | 6.4 (SD = 2.6) | 6.2 (SD = 2.6) | p = 0.89 |

| BVRT No of errors Mean (SD) |

5.4 (SD = 3.3) | 5 (SD = 3.9) | 4.8 (SD = 3.9) | p = 0.60 |

| BVRT – Cognitive function damage adjusted to age and IQ – percentage of patients with damage | 13% | 9% | 0 | p = 0.51 |

| BVMGT Bender Visual-Motor Gestalt Testa Mean points (SD) |

88.3 (SD = 20.5) | 92.9 (SD = 26) | 101.6 (SD = 19.4) | p = 0.40 |

| Wilcoxon test before and after PCI – p = 0.059 | ||||

| BVMGT Visual-motor function damage adjusted to age and education – percentage of patients with damage | 31% | 41% | 67% | p = 0.44 |

SD – standard deviation.

In BVMGT normal score for Polish population is less than 100 points (the less points is for the better results).

In MRI, degenerative periventricular vascular changes were observed in 2/10 patients.

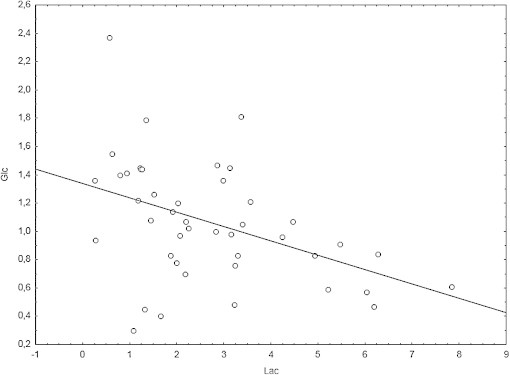

The analysis of spectroscopic data showed no statistically significant differences in the occipital normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) between examinations, while in the frontal NAWM statistically significant differences were observed only between exam 1 (before PCI) and exam 2 (up to 30 days post PCI) in both the absolute metabolite concentrations and their ratios. These differences were detected by Wilcoxon matched pair test in tCr (p = 0.0277), Lac (p = 0.018), and Glc (p = 0.0464) as well as in Lac/NAA (p = 0.028), Lac/tCr (p = 0.018), and Lip/tCr (p = 0.0425) (Table 4). Moreover, statistically significant inverse correlations in subsequent examinations were found between Lac and Glc in the frontal NAWM (r = −0.44, p = 0.038, Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Results of the analysis of spectroscopic data.

| Before PCI | Up to 30 days | More than 90 days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute metabolite concentrations median (min–max). Valid cases 7 | |||

| tCr | 3.2 (1.35–5.2) | 1.75 (1.0–3.09) | 2.51 (1.25–3.09) |

| p = 0.023 | |||

| Lac | 1.1 (0.2–4.13) | 3.2 (1.2–7.9) | 2.95 (1.1–6.2) |

| p = 0.018 | |||

| Glc | 1.45 (0.44–2.39) | 0.79 (0.4–1.81) | 1.0 (0.3–1.39) |

| p = 0.046 | |||

| Metabolite ratios median (min–max). Valid cases 7 | |||

| Lac/NAA | 0.4 (0.09–2.69) | 2.1 (0.4–5.0) | 2 (0.4–2.9) |

| p = 0.028 | |||

| Lac/tCr | 0.49 (0.1–2.07) | 0.48 (1.2–7.95) | 1.2 (0.5–3.9) |

| p = 0.018 | |||

| Lip/tCr | 3 (2–11.5) | 16.1 (3–23) | 9.8 (6–25.5) |

| p = 0.042 | |||

Fig. 2.

Correlation between Lac and Glc absolute concentration in the frontal normal-appearing white matter.

5. Discussion

In oncology, radiotherapy of regions potentially harboring micrometastases has got a well established role in treatment of many types of cancer. Particularly well examined and widely used is the positive effect of elective radiotherapy in nodal regions in patients with squamous-cell cancer of the head and neck. A total dose of 50 Gy in 2 Gy fractions reduces nodal recurrences by 60%.13 Assuming similar radiosensitivity of brain micrometastases from NSCLC, it can be theoretically estimated that the incidence of BM after PCI with a dose of 30 Gy would be reduced by 20–30%.13 The high probability of developing BM in patients with NSCLC (up to 58%) has raised the question about the effectiveness of PCI. The RTOG 0214 study comparing PCI versus observation in patients with advanced NSCL demonstrated a reduced probability of BM by a factor of 2.52 after elective treatment, which is higher than predicted based on theoretical calculations.5 Data from earlier studies on PCI in SCLC have indicated deterioration of cognitive function after PCI (mainly in cases of concomitant use of PCI and chemotherapy) raising doubts about safety of PCI.14,15

The RTOG 0214 study5 was closed prematurely due to slow accrual, reflecting the uncertainly and anxiety of patients and physicians regarding the potential toxicity of brain irradiation. Whole brain irradiation was the standard treatment for BM for many years16 with an estimated response rate for BM after whole brain irradiation of 60%.17 The paucity of data on acute and especially late toxicity after whole brain irradiation for BM is likely due to the short survival of patients with NSCLC. Data on toxicity after PCI in SCLC are focused mainly on the neuropsychological changes.

The toxicity of PCI in the current series was mild and mostly self-limiting. We did not observe significant decline in blood count at the end of PCI. It is important to note that inclusion criteria required enrollment of patients without significant hematological toxicity after chemotherapy. Surprisingly, in the available literature (according to our best knowledge), there are no data on hematologic tolerance of WBRT. The present findings demonstrated good hematologic tolerance of PCI. Only slight and statistically not significant decrease in platelet count was noted. White blood cells count even increased at the end of treatment. It may be explained by the use of steroids in some patients.

Although 30% of the patients experienced acute toxicity: headache, nausea, or erythema of the irradiated skin, the symptoms did not present a serious problem, and were quickly and successfully relieved by standard pharmacologic treatments (steroids and non-steroids).

The late toxicity is the main concern of the treatment. In the presented study vertigo was the most common late side effect (6%) which may be related to irradiation of the inner ear during the course of PCI. It cannot be excluded, however, that the late symptoms were caused by the disease itself, paraneoplastic syndromes, late effects of chemotherapy, or prolonged stress. It is important to note that the severity of the symptoms was low and the patients did not consider them noticeably detrimental to their quality of life.

Alopecia after PCI was transient with median time to hair regrowth of 2.5 months. One patient died 2 months after treatment, before the hair regrowth, because of dissemination to the lung. It is worth mentioning that fear of alopecia was the most frequently given reason for not participating in the study.

Endocrine changes are the least of all evaluated alterations after PCI and whole brain irradiation. For the sake of simplicity, we chose testosterone level as the most direct indicator of pituitary dysfunction. Testosterone is the feedback hormone for luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), so the decline in LH/FSH level after pituitary irradiation will cause proportional decline in testosterone level. Other hormones, as estradiol or thyroid hormone, are much more dependent on other factors, like menstrual cycle or iodine contrast used for computed tomography. Although our analysis included only 10 male patients, to the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first estimation of endocrine changes after PCI in the literature. In the current analysis a non-significant decline in the serum testosterone levels after PCI was observed. Fatigue is the most common adverse effect reported by patients with SCLC after PCI.18 In older men, a decline in testosterone levels is associated with fatigue and deterioration of cognitive function,19,20 and the same effect might be caused by endocrine changes after PCI. Simple supplementation with testosterone could possibly be beneficial for those patients.

To the best of our knowledge, spectroscopic analysis before and after PCI has not been previously reported. The observed elevation in the Lac concentration as well as the Lac/NAA and Lac/tCr ratios were most prominent within 30 days after irradiation. This phenomenon could be explained by radiation damage leading to impaired lactate washout due to post-irradiation edema, an increased lactate concentration caused by radiation-induced cell-kill, or by disturbed glucose metabolism.21,22 The decreased glucose concentration in the early period after PCI coinciding with the elevation of lactate level and the reverse tendency later suggest that the last mechanism may play a significant role in this phenomenon. The decrease of glucose concentration can be caused both by its increased consumption due to repair processes in neural and glial cells or by impaired delivery caused by radiation-induced edema. The exact reason of the observed inverse correlation between glucose and lactate concentrations in the frontal NAWM in all time-points is unclear but this observation can be a groundwork for further studies. Similarly, an increase in the Lip/tCr ratio could be explained by cell membrane disintegration due to ionization. Both Lac/tCr and Lip/tCr ratios reached the highest level immediately after irradiation (<30 days) and varied widely among individual patients. Whether the observed alterations are solely the effect of irradiation or the previous treatment like chemotherapy influenced the results is not known. The most prominent alterations were, however, observed immediately after irradiation as compared to the spectra acquired before PCI which suggests that the damaging action of ionizing radiation played the main role here.

White matter changes seen in radiological imagining after whole brain radiotherapy, defined as hyperintensity from focal to confluent, are reported in 38–50% patients.23 These changes are usually asymptomatic, and discovered only by imaging studies.23,24 Changes after PCI observed in the present study were moderate and reflected demyelination in the periventricular region with no clinical relevance.

Precise neuropsychologic tests performed during the RTOG 0214 study showed no significant differences in global cognitive function or QOL after PCI, but there was a significant decline in memory at 1 year after treatment.25 In the present study, neuropsychologic tests revealed a slight decrease in cognitive function (in WAIS-R examination) 6 months after treatment. The patients themselves did not complain about deterioration of cognitive functions, consequently, the observed decline can be considered clinically irrelevant and not influencing the patients’ quality of life.

In SCLC patients there were attempts to decrease the deteriorative effects of PCI on cognitive function by using specific techniques of irradiation (intensity-modulated radiotherapy, helical TomoTherapy, and Rapid Arc) allowing to spare neural stem cells (found mainly in hippocampus).26,27 Similar techniques may be used in NSCLC patients. Possibly sparing the pituitary gland and the inner ears from high dose of irradiation may also be beneficial for this group of patients, hopefully by alleviation of the hormonal changes after PCI and possibly also vertigo.

To date, clinical trials have not demonstrated positive effect of PCI on overall survival, the reasons for that are complex. The reduction in the incidence of BM stated in almost all papers on PCI confirm the radiosensitivity of cerebral micrometastases. Consequently, PCI could possibly increase survival in patients who are at high risk of death from metastases to the brain. The cause of death in NSCLC (also in case of patients after PCI) is mainly dissemination to other sites or (rarely) locoregional progression. Thus, patients with a high probability of brain dissemination and a low probability of non-central nervous system (CNS) dissemination are probably more likely to achieve a survival gain from PCI. According to Gaspar et al., isolated brain metastases occur in 11% of patients and this subgroup should gain maximum benefit from PCI.28 This assumption is confirmed by data showing benefits for patients with isolated brain metastases from NSCLC when chemo-irradiation of the primary tumor and WBRT is applied unless there are no excessive lymph node metastases.29

Currently there are no good tools to select such patients. Consequently, the aim of future studies should be to determine the subset of patients with a high probability of BM, a high probability of locoregional cure, and low risk of distant non-CNS metastases. Still, the reduced probability of BM could be beneficial even for patients with dissemination to other sites (which proved to be true for patients with SCLC), but for this group of patients a close follow-up with brain imaging studies for occult metastases may be a reasonable option.

6. Conclusions

Prophylactic cranial irradiation can be safely performed in NSCLC patients with relatively low impact on their cognitive status and self-assessed well-being. The decrease of blood testosterone level can be suggestive of pituitary dysfunction and requires further studies, especially in patients subject to WBRT with relatively good prognosis and anticipated long-term survival. WBRT alters prominently the cerebral metabolism in the early period after irradiation which may contribute to mechanisms underlying the observed acute toxicity symptoms. The metabolic alterations triggered by PCI seem temporal and tended to reverse but more detailed studies are needed to gain deeper insight into the metabolism of the brain subject to irradiation in the particular clinical setting.

To alleviate side effects and to further increase the tolerance of PCI, specialized techniques of irradiation sparing the inner ear, pituitary gland and hippocampus should be considered.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

The paper was supported by grant No 402 350 638.

References

- 1.Auperin A., Arriagada R., Pignon J., Le Péchoux C., Gregor A., Stephens R.J. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with SCLC in complete remission. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:476–484. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viani G.A., Boin A.C., Ikeda V.Y., Vianna B.S., Silva R.S., Santanella F. Thirty years of prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38(3):372–381. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132012000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albain K., Rusch V., Crowley J., Turrisi A.T., III Concurrent cisplatin/etoposide plus chest radiotherapy followed by surgery for stages IIIA (N2) and IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer: mature results of Southwest Oncology Group phase II study 8805. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1880–1892. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stusche M., Eberhardt W., Pottgen C., Stamatis G., Wilke H., Stüben G. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after trimodality treatment: long-term follow up and investigations of late neuropsychological effects. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2700–2709. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gore E.M., Bae K., Wong S.J., Sun A., Bonner J.A., Schild S.E. Phase III comparison of prophylactic cranial irradiation versus observation in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: primary analysis of radiation therapy oncology group study RTOG 0214. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(3):272–278. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss G., Hernodon J., Sherman D.D., Mathisen D.J., Carey R.W., Choi N.C. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy and definitive surgery in stages IIIA NSCLC: report of Cancer and Leukemia Group B phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1237–1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.8.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komaki R., Scott C., Byhardt R., Emami B., Asbell S.O., Russell A.H. Failure patterns by prognostic group determined by recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of 1547 patients on four Radiation Therapy Oncology group (RTOG) studies in inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox J., Stanley K., Petrovich Z., Paig C., Yesner R. Cranial irradiation in cancer of lung of all cell types. JAMA. 1981;245:469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lester J.F., MacBeth F.R., Coles B. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for preventing brain metastases in patients undergoing radical treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer: a Cochrane Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(3):690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umsawasdi T., Valdiviesco M., Chen T., Barkley H.T., Jr., Booser D.J., Chiuten D.F. Role of elective brain irradiation during combined chemoradiotherapy for limited disease non-small-cell lung cancer. J Neuro-Oncol. 1984;2:253–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00253278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell A., Pajak T., Selim H. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for lung cancer patients at high risk for development of cerebral metastasis: results of a prospective randomized trial conducted by the RTOG. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:637–643. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90681-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokół M. In vivo 1H MR spectra analysis by means of second derivative method. Magn Reson Mat Phys Biol Med. 2001;12:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s1352-8661(01)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Withers H.R., Suwiński R. Radiation dose response for subclinical metastases. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1998;8:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s1053-4296(98)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Oosterhout A.G., Ganzevles P.G., Wilmink J.T., De Geus B.W., Van Vonderen R.G., Twijnstra A. Sequelae in long-term survivors of small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34(5):1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahles T.A., Silberfarb P.M., Herndon J., II, Maurer L.H., Kornblith A.B., Aisner J. Psychologic and neuropsychologic functioning of patients with limited small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy with or without warfarin: a study by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1954–1960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lokich J.J. The management of cerebral metastasis. JAMA. 1975;234:748–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaspar L., Scott C., Rotman M., Asbell S., Phillips T., Wasserman T. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slotman B.J., Mauer M.E., Bottomley A., Faivre-Finn C., Kramer G.W., Rankin E.M. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in extensive disease small-cell lung cancer: short-term health-related quality of life and patient reported symptoms: results of an international Phase III randomized controlled trial by the EORTC Radiation Oncology and Lung Cancer Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):78–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holland J., Bandelow S., Hogervorst E. Testosterone levels and cognition in elderly men: a review. Maturitas. 2011:322–337. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogervorst E., Bandelow S., Combrinck M., Smith A.D. Low free testosterone is an independent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39(11–12):1633–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mader I., Roser W., Kappos L., Hagberg G., Seelig J., Radue E.W., Steinbrich W. Serial proton MR spectroscopy of contrast-enhancing multiple sclerosis plaques: absolute metabolic values over 2 years during a clinical pharmacological study. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(7):1220–1227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowling C., Bollen A.W., Noworolski S.M., McDermott M.W., Barbaro N.M., Day M.R. Preoperative proton MR spectroscopic imaging of brain tumors: correlation with histopathologic analysis of resection specimens. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(4):604–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowley H.A., Dillon W.P. Iatrogenic white matte diseases. Neuroimaginig Clin North Am. 1993;3:379–404. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong C.L., Hunter J.V., Ledakis G.E., Cohen B., Tallent E.M., Goldstein B.H. Late cognitive and radiographic changes related to radiotherapy: initial prospective findings. Neurology. 2002;59(1):40–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun A., Bae K., Gore E.M., Movsas B., Wong S.J., Meyers C.A. Phase III trial of prophylactic cranial irradiation compared with observation in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: neurocognitive and quality-of-life analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(3):279–286. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarnawski R., Michalecki L., Blamek S., Hawrylewicz L., Piotrowski T., Ślosarek K., Kulik R. Feasibility of reducing the irradiation dose in regions of active neurogenesis for prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Neoplasma. 2011;58(6):507–515. doi: 10.4149/neo_2011_06_507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazda T., Pospíšil P., Doleželová H., Jančálek R., Slampa P. Whole brain radiotherapy: consequences for personalized medicine. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2013;18(3):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaspar L.E., Chansky K., Albain K.S., Vallieres E., Rusch V., Crowley J.J. Time from treatment to subsequent diagnosis of brain metastases in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective review by the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2955–2961. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arrieta O., Villarreal-Garza C., Zamora J., Blake-Cerda M., de la Mata M.D., Zavala D.G. Long-term survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and synchronous brain metastasis treated with whole-brain radiotherapy and thoracic chemoradiation. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:166. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]