Abstract

2H (two-histidine) phosphoesterase enzymes are distributed widely in all domains of life and are implicated in diverse RNA and nucleotide transactions, including the transesterification and hydrolysis of cyclic phosphates. Here we report a biochemical and structural characterization of the Escherichia coli 2H protein YapD, which was identified originally as a reversible transesterifying “nuclease/ligase” at RNA 2′,5′-phosphodiesters. We find that YapD is an “end healing” cyclic phosphodiesterase (CPDase) enzyme that hydrolyzes an HORNA>p substrate with a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester to a HORNAp product with a 2′-phosphomonoester terminus, without concomitant end joining. Thus we rename this enzyme ThpR (two-histidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase acting on RNA). The 2.0 Å crystal structure of ThpR in a product complex with 2′-AMP highlights the roles of extended histidine-containing motifs 43HxTxxF48 and 125HxTxxR130 in the CPDase reaction. His43-Nε makes a hydrogen bond with the ribose O3′ leaving group, thereby implicating His43 as a general acid catalyst. His125-Nε coordinates the O1P oxygen of the AMP 2′-phosphate (inferred from geometry to derive from the attacking water nucleophile), pointing to His125 as a general base catalyst. Arg130 makes bidentate contact with the AMP 2′-phosphate, suggesting a role in transition-state stabilization. Consistent with these inferences, changing His43, His125, or Arg130 to alanine effaced the CPDase activity of ThpR. Phe48 makes a π–π stack on the adenine nucleobase. Mutating Phe28 to alanine slowed the CPDase by an order of magnitude. The tertiary structure and extended active site motifs of ThpR are conserved in a subfamily of bacterial and archaeal 2H enzymes.

Keywords: RNA repair, 3′ end healing, 2H phosphoesterase

INTRODUCTION

RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate ends figure prominently in RNA metabolism, as the products of site-specific RNA incision by transesterifying ribonucleases and as the substrates for diverse RNA break repair systems. Two pathways of RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate repair are distinguished by the end requirements of their respective RNA ligase components. In pathways driven by classic ATP-dependent RNA ligases, which join 3′-OH and 5′-PO4 ends, the RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate must either be removed entirely, or hydrolyzed to a 2′-phosphomonoester, prior to the ligation step. These preparatory reactions are referred to as 3′ end healing and are performed by enzymes other than the ligase (Schwer et al. 2004). In the repair pathway spearheaded by the unconventional GTP-dependent RNA ligase RtcB, which joins 3′-PO4 and 5′-OH ends, the initial RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate is hydrolyzed to a 3′-PO4 by RtcB per se (Tanaka et al. 2011a; Chakravarty et al. 2012; Chakravarty and Shuman 2012).

Bacteriophage T4 polynucleotide kinase phosphatase (Pnkp) exemplifies the 3′ end healing enzymes that completely remove the cyclic phosphate, via sequential 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase (to generate a 3′-PO4 RNA end) and 3′-phophomonoesterase reactions (Das and Shuman 2013). Pnkp phosphatase belongs to the DxDxT phosphotransferase superfamily that acts via a covalent enzyme–aspartylphosphate intermediate. T4 Pnkp functions in vivo in tandem with T4 RNA ligase 1 to repair tRNA damage inflicted by the Escherichia coli host as an innate antiviral response to phage infection (Amitsur et al. 1987).

The 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase (CPDase) domain of fungal and plant tRNA ligases typifies a separate group of 3′ end healing enzymes that hydrolyze the RNA cyclic phosphodiester to form a 2′-PO4 RNA end (Greer et al. 1983a; Wang et al. 2006). The 2′-PO4 is required for the subsequent 3′-OH/5′-PO4 ligation step of tRNA splicing, which ensures that end sealing is targeted to the proper RNA substrates (Remus and Shuman 2013). The CPDase domains of fungal and plant tRNA ligases belong to the 2H (two-histidine) phosphoesterase superfamily, defined by a pair of Hx(T/S) motifs (Mazumder et al. 2002). Mammalian 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (CNPase) is a biochemically and structurally characterized 2H enzyme that has been the focus of much attention because it is a major protein component of myelin (Braun et al. 2004). Whereas CNPase hydrolyzes 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotides to 2′-NMP products, its biological functions and physiological substrates remain unclear. The finding that mammalian CNPase can replace the CPDase domain of yeast tRNA ligase in vivo suggests that CNPase may function in RNA metabolism (Schwer et al. 2008).

2H phosphoesterase homologs are distributed widely among taxa in all domains of life (Mazumder et al. 2002). Although relatively few have been studied biochemically or structurally, the biochemical activities that have been demonstrated entail the hydrolysis of diverse cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesters and RNA phosphodiesters (Hofmann et al. 2000, 2002; Hilcenko et al. 2013; Myllykoski et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). One of the early examples of an enzyme that would eventually define a branch of the 2H family was discovered by Greer and Abelson in E. coli as an activity that could join tRNA halves with 2′,3′-cyclic-PO4 and 5′-OH ends to form a 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage at the splice junction (Fig. 1A; Greer et al. 1983b). Arn and Abelson (1996) purified the 2′,5′-RNA ligase activity, cloned the gene encoding the 20 kDa enzyme, and showed that disruption of this gene effaced ligase activity in cell extracts, but had no effect on bacterial growth under laboratory conditions. A key insight from their biochemical analysis was that the 2′,5′-ligase catalyzed the incision of a RNA 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage (by transesterification, as depicted in Fig. 1A), while being inert with an otherwise identical RNA with a 3′,5′-phosphodiester (Arn and Abelson 1996). Moreover, the “nuclease” activity of the E. coli enzyme was favored over the sealing activity under equilibrium conditions. Whereas Arn and Abelson did not attach a name to the E. coli enzyme (other than 2′,5′-RNA ligase) or its gene, the yapD open reading frame encoding the E. coli enzyme has since been annotated as ligT, which signifies “ligase tRNA.” This nomenclature has been propagated widely to the scores of bacteria and archaea that encode a homologous 2H protein, notwithstanding that (i) E. coli and many other bacteria that encode this 2H enzyme do not have any intron-containing tRNAs; (ii) there are, to our knowledge, no examples of E. coli RNAs with 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkages; and (iii) E. coli has a valid RNA splicing enzyme in RtcB that generates a 3′,5′-phosphodiester at the splice junction (Tanaka and Shuman 2011; Tanaka et al. 2011b).

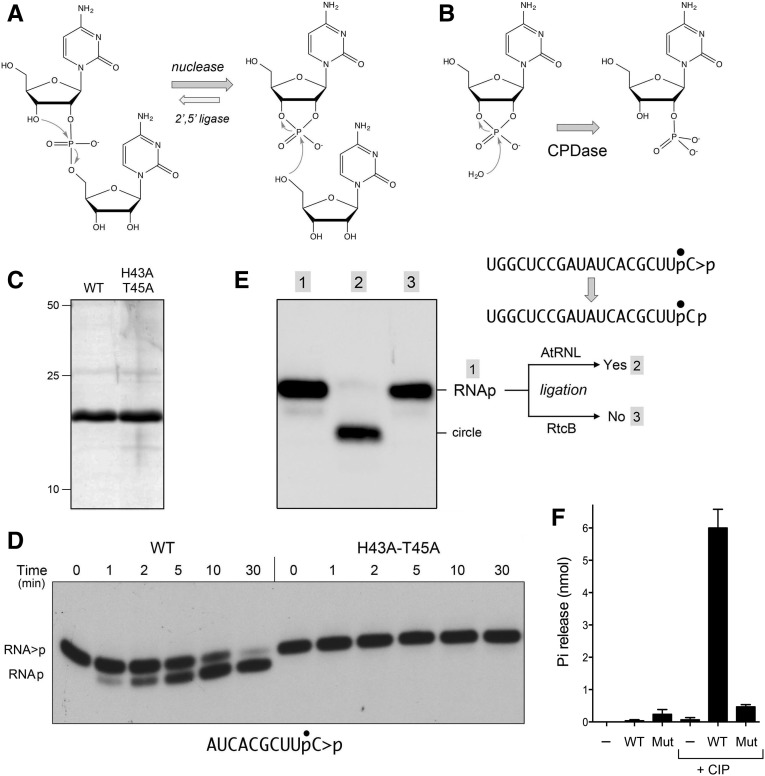

FIGURE 1.

E. coli ThpR is an RNA 2′,3′-CPDase. (A) Scheme for reversible transesterification by the E. coli 2H enzyme at an RNA 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkage, initially discovered by Abelson and colleagues. (B) Scheme for hydrolysis of an RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester to a 2′-phosphomonoester. (C) ThpR purification. Aliquots (4 µg) of the Superdex-200 fractions of wild-type (WT) ThpR and mutant H43A-T45A were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The Coomassie-blue stained gel is shown. The positions and sizes (kDa) of marker polypeptides are indicated on the left. (D) RNA 2′,3′-CPDase activity. Reaction mixtures (20 µL) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM EDTA, 20 nM 32P-labeled 10-mer HORNA>p substrate (as shown, with the labeled phosphate denoted by •), and 200 nM wild-type ThpR or mutant H43A-T45A were incubated at 37°C for the times specified. The reactions were quenched with an equal volume of 90% formamide and 50 mM EDTA. The products were analyzed by electrophoresis through a 40-cm 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea in TBE and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of the radiolabeled RNA>p substrate and the RNAp product are indicated on the left. (E) ThpR generates a 2′-PO4 RNA product. A reaction mixture (40 μL) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM EDTA, 20 nM 32P-labeled 20-mer HORNA>p substrate (as shown, with the labeled phosphate denoted by •), and 200 nM wild-type ThpR was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, then extracted with phenol–chloroform. The de-proteinized 20-mer RNAp product in the aqueous phase was then subjected to diagnostic tests of ligation by AtRNL (CPDase-defective mutant T1001A) and E. coli RtcB. The RNAp samples in lanes 1 and 2 were incubated (in 20 µL) with 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ATP, and either 1 µM AtRNL-T1001A (lane 2) or no ligase enzyme (lane 1) at 37°C for 30 min. The RNAp sample in lane 3 was incubated (in 20 μL) with 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.1 mM GTP, and 1 µM RtcB at 37°C for 30 min. The reactions were quenched with formamide and EDTA and the products were analyzed by urea-PAGE. An autoradiograph of the gel is shown. The position and identities of the radiolabeled RNAp substrate and the ligated RNA circle are indicated on the right. (F) Hydrolysis of 2′,3′-cAMP. Reaction mixtures (20 µL) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM 2′,3′-cAMP (Sigma), 5 µg wild-type ThpR (WT) or mutant H43A-T45A (Mut) where indicated, and 10 U calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP, New England Biolabs) where indicated, were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The reactions were quenched by adding 980 µL of Malachite Green reagent (Enzo). Phosphate release was determined after incubation for 30 min at 22°C by measuring the absorbance at 620 nm and then interpolating the value to a phosphate standard curve. Each datum in the bar graph is the average of three separate experiments ± SEM.

Our view is that the 2′,5′ “nuclease” and “ligase” reactions of the E. coli 2H enzyme (Fig. 1A), though historically key to its discovery, may not be pertinent to the function of the enzyme in RNA metabolism. Rather, we suspected, by analogy to the yeast and plant RNA end healing enzymes, that the E. coli 2H phosphoesterase is an RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase. Here we affirm this point by showing that the E. coli enzyme hydrolyzes an HORNA>p substrate with a 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester to a HORNAp product with a 2′-phosphomonoester terminus (as in Fig. 1B) without end joining. Accordingly, we rename the E. coli enzyme YapD/LigT as ThpR, signifying a “two-histidine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase acting on RNA.” We report the 2.0 Å crystal structure of ThpR in a complex with 2′-AMP, which, in conjunction with structure-guided mutagenesis, provides insights into substrate recognition and catalysis by this branch of the 2H superfamily.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase activity of E. coli ThpR generates a 2′-PO4 product

We produced recombinant ThpR (formerly YadP or LigT) as a His10Smt3•ThpR fusion and isolated it from a soluble bacterial extract by Ni-affinity chromatography. After cleaving the tag during overnight dialysis in the presence of the Smt3 protease Ulp1, we recovered tag-free ThpR in the flow-through fraction during a second Ni-affinity step. After a subsequent step of gel filtration, during which ThpR eluted as a monomer, the preparation comprised a predominant ∼20 kDa polypeptide (Fig. 1C). Reaction of 200 nM ThpR with 20 nM HORNA>p substrate (a 10-mer oligoribonucleotide with 5′-OH and 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate termini and a single 32P label at the penultimate phosphate) resulted in time-dependent conversion of HORNA>p to a HORNAp phosphomonoester product that migrated slightly ahead of the substrate during urea-PAGE (Fig. 1D). We did not detect the formation of a 10-mer RNA circle, which migrates faster than RNAp (Remus and Shuman 2014), or a slower migrating 20-mer dimer species, leading us to conclude that the dominant, if not exclusive, reaction of ThpR with this substrate was as a hydrolytic CPDase rather than as an end-joining ligase. (Note, it is not the case that a 10-mer is inherently too short to circularize; plant tRNA ligase readily catalyzes intramolecular ligation of a 10-mer to form a 10-mer circle [Remus and Shuman 2014].) A mutated version of ThpR with alanine substitutions at His43 and Thr45 of the proximal HxT motif that was purified in parallel with the wild-type enzyme through all chromatography steps (Fig. 1C) displayed no CPDase activity during a 30 min reaction with HORNA>p (Fig. 1D), from which we infer that the CPDase activity inheres to the recombinant ThpR enzyme.

The PAGE procedure does not distinguish whether the CPDase reaction product has a 3′-phosphate or 2′-phosphate terminus. In order to determine the nature of the RNAp end, we reacted ThpR with a 20-mer HORNA>p substrate to achieve conversion to a HORNAp product, then exploited the distinctive end specificities of two RNA ligases, plant AtRNL (specifically the CPDase-defective mutant T1001A) and E. coli RtcB, to discern the position of the phosphomonoester. AtRNL-T1001A joins 2′-phosphate and 5′-OH RNA ends via the following steps: (i) a 5′-kinase transfers the γ phosphate from ATP to the 5′-OH RNA end to yield a 5′-phosphate; (ii) an ATP-dependent ligase joins the healed 3′-OH/2′-PO4 and 5′-PO4 ends to yield a 3′,5′-phosphodiester, 2′-PO4 splice junction. The 2′-PO4 is strictly required for the sealing reaction of plant tRNA ligase. E. coli RtcB joins 3′-phosphate and 5′-OH RNA ends by a different set of chemical steps to generate a conventional 3′,5′-phosphodiester splice junction. RtcB strictly requires a 3′-PO4 end for ligation; it does not seal a 2′-PO4 end.

In the experiment in Figure 1E, a 20-mer RNAp product generated by ThpR was incubated with the respective ligases and the requisite NTPs and metal cofactors. The outcome of successful ligation is intramolecular end joining to yield a circular RNA product that migrates faster than the linear RNA substrate. Whereas AtRNL-T1001A effected virtually complete circularization of the RNAp strand (Fig. 1E, lane 2), RtcB was inert (lane 3). These results indicate that the CPDase reaction of ThpR generates a 2′-PO4 RNA product.

We tested the ability of ThpR to hydrolyze a cyclic mononucleotide, 2′,3′-cAMP, by assaying the capacity of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP) to release inorganic phosphate (Pi) from the adenylate nucleotide after reaction with ThpR, using a colorimetric assay to quantify Pi. Whereas the input 2′,3′-cAMP substrate with a phosphodiester linkage was resistant to hydrolysis by CIP, reaction with wild-type ThpR rendered the adenylate sensitive to CIP (Fig. 1F), signifying that the ThpR reaction product was a phosphomonoester. The mutated version of ThpR with alanine substitutions at His43 and Thr45 was ineffective in converting 2′,3′-cAMP to a CIP-sensitive product (Fig. 1F). In the experiment shown in Figure 1F, 24 pmol of 2′,3′-cAMP was hydrolyzed per pmol of input ThpR.

Atomic structure of a product complex of ThpR bound to 2′-AMP

ThpR crystals were grown by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method after mixing a solution containing 0.25 mM selenomethione (SeMet)-substituted ThpR and 10 mM 2′-AMP with an equal volume of a precipitant solution containing 2 M NaCl and 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 4.8–5.0. Diffraction data to 2.02 Å resolution were collected from a single crystal in space group P4212 with two ThpR protomers in the asymmetric unit. Phases were derived using 2.5 Å SAD data that identified four selenium atoms corresponding to Met92 and Met105 of each protomer. Automated and manual model building into electron density yielded a refined 2.02 Å model with R/Rfree of 0.176/0.230 and excellent geometry (Table 1). The B protomer comprised a continuous polypeptide from Glu3 to Gln176; the A protomer spanned Pro4 to Gln176 with a two amino acid gap at Asn119-Arg120. 2′-AMP was modeled into Fo-Fc density in the active site of the B promoter (Fig. 2E). There was no density for a nucleotide substrate in the active site of the A promoter. The tertiary structures of the A and B protomers were virtually identical (RMSD of 0.24 Å at 142 Cα positions). All depictions and descriptions of the ThpR structure that follow refer to the 2′-AMP complex with the B protomer.

TABLE 1.

SeMet-EcoThpR crystallographic data and refinement statistics

FIGURE 2.

ThpR structure and active site. (A) Stereo view of the tertiary structure of E. coli ThpR is shown as a ribbon trace with magenta β strands, cyan α helices, blue 310 helices, and beige intervening loops and turns. The N terminus of the polypeptide is indicated; the α helices are numbered. The 2′-AMP in the active site is depicted as a stick model. (B) A surface electrostatic model of ThpR, in the same orientation as in panel A, was generated in Pymol. (C) The primary structure of E. coli ThpR (Eco) polypeptide is aligned to that of the homologous PH0099 protein from Pyrococcus horikoshii (Pho). The 43HxTxxF48 and 125HxTxxR130 motifs are highlighted in yellow. Gaps in the alignment are indicated by dashes. Positions of side chain identity/similarity are denoted by dots. The secondary structure elements of ThpR are shown above the amino acid sequence, with β strands rendered as arrows and helices as cylinders, colored as in panel A. Three conserved α helices are numbered. A fourth distinctive α helix in PH0099 is shown in gray. (D) Stereo view of the active site of ThpR with selected amino acid side chains depicted as stick models with beige carbons. The 2′-AMP is shown as a stick model with gray carbons. Atomic contacts are indicated by dashed lines. (E) Fo-Fc electron density map for the 2′-AMP at the binding site is shown as a red mesh contoured at 3.5 σ level. The 2′-AMP is shown as a stick model.

Overview of the ThpR structure

The tertiary structure is organized around two central four-strand anti-parallel β-sheets that form the 2′-AMP binding site: sheet 1 on the left in Figure 2A having topology β10↓,β9↑,β1↓,β3↑ and sheet 2 on the right having topology β5↑,β6↓,β7↑,β2↓. Sheet 1 is flanked on its lateral surface by helices α2 and α3; sheet 2 is flanked by helix α1 and two short 310 helices. A two-strand sheet (β4↑,β8↓) forms the basal surface of ThpR. The signature 2H motifs are located in strands β3 and β7. A surface electrostatic model of ThpR in Figure 2B highlights a nucleotide binding pocket in which the ribose 3′-OH and the 2′-phosphate moieties of AMP are oriented downward against the enzyme surface, whereas the nucleobase (which is in the syn conformation over the ribose) (Fig. 2E) and the ribose 5′-OH are projecting outward. Positive electrostatic potential surrounds the 2′-AMP, which we presume is synonymous with the terminal nucleotide of the RNA2′p product of the CPDase reaction. A positively charged groove extending down from the ribose 5′-OH in Figure 2B is a potential docking site for the RNA segment preceding the 3′-terminus.

A DALI search (Holm et al. 2008) of the ThpR structure against the protein database identified Pyrococcus horikoshii PH0099 (Rehse and Tahirov 2005; Gao et al. 2006) and Thermus thermophilus TT0787 (Kato et al. 2003) as the top hits, with Z-scores >20 and RMSD values of ∼2.0 Å at ≥165 Cα positions (Table 2). PH0099 and TT0787 were deemed a “putative 2′-5′-RNA ligase” and “the 2′-5′-RNA ligase” from their respective thermophilic archaeal and bacterial taxa, albeit absent enzymatic characterization of either protein. An alignment of the E. coli ThpR and PH0099 primary and secondary structures highlights (i) 74 positions of side chain identity/similarity (denoted by dots in Fig. 2C); and (ii) an α helix inserted into the PH0099 fold (colored gray in Fig. 2C) that has no counterpart in E. coli ThpR.

TABLE 2.

Structural homologs of EcoThpR

Retrieved in the second tier of homologous 2H crystal structures (with Z-scores between 14 and 18) were the following: Bacillus subtilis YjcG, a protein of indeterminate activity (Li et al. 2008); rat AKAP18, which binds 5′-AMP and is suggested to serve as a noncatalytic AMP sensor (Gold et al. 2008); human USB1, a transesterifying RNase that catalyzes the terminal 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate end maturation step of U6 snRNA biogenesis (Hilcenko et al. 2013); and Arabidopsis thaliana CPDase (Hofmann et al. 2000, 2002), which hydrolyzes ADP-ribose 1″,2″ cyclic phosphate to ADP-ribose 1″-phosphate and nucleoside 2′,3′-cyclic phosphates to 2′-NMPs (Genschik et al. 1997). Also retrieved in the second group was the NMR structure of Pyrococcus furiosus PF0027, a thermophilic enzyme with vigorous 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase activity on a tetranucleotide RNA>p substrate yielding an RNA2′p product, and comparatively weak activity in joining tRNA halves with 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate and 5′-OH ends (Kanai et al. 2009). Two unusual, and somewhat mysterious, features of the strand joining activity of PF0027 (i.e., ones not shared with the E. coli 2H enzyme) include a dependence on GTP and a capacity to join tRNA halves with RNA2′p and 5′-OH ends (Kanai et al. 2009). Mammalian CNPase, for which multiple structures are available (Myllykoski et al. 2013), was retrieved in a distinctly lower tier with respect to its homology with ThpR (Z-score 7.3 and 3.5 Å RMSD at 126 positions).

Active site of ThpR

The architecture of the 2′-AMP site provides insights into substrate recognition and phosphoesterase chemistry. The adenosine nucleoside in syn conformation packs against two aromatic side chains lining the nucleotide pocket: Phe48 in β3 makes an intimate (3.3 Å) π–π stack with the adenine nucleobase and Phe8 in β1 makes van der Waals contact to the ribose C5′ (Fig. 2D). The ribose O3′ is coordinated jointly by His43 and Thr45 of the proximal HxT motif. The O3′, which is the leaving group in the CPDase reaction, makes a hydrogen bond to His43-Nε in the product complex, implicating His43 as the general acid catalyst that donates a proton to the bridging O3′ atom of the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate substrate. A productive rotameric and tautomeric state for His43 is enforced by a hydrogen bond from His43-Nδ to the main chain carbonyl of Asn41 (Fig. 2D). His125-Nε of the distal HxT motif donates a hydrogen bond to the O1P oxygen of the AMP 2′-phosphate. We infer that the O1P in the 2′-AMP product complex derives from the attacking water nucleophile in the CPDase reaction, insofar as the O1P is situated in the most favorable orientation with respect to the ribose O3′, at an O3′–P–O1P angle of 130°. (The O3′–P–O2P and O3′–P–O2P angles are 56° and 120°, respectively.) This implicates His125 as the general base catalyst that abstracts a proton from the water nucleophile. A proper rotamer/tautomer of His125 is imposed by a hydrogen bond from His125-Nδ to the main chain carbonyl of His123 (Fig. 2D). The other 2′-phosphate oxygens are coordinated by Thr127-Oγ of the distal HxT motif and a bidentate electrostatic interaction with the Arg130 terminal guanidinium nitrogens (Fig. 2D). These contacts, especially those of Arg130, might play a role in stabilizing the extra negative charge developed on the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate in the putative pentacoordinate phosphorane transition state of the CPDase reaction.

Structure-guided mutagenesis

Single alanine substitutions were introduced in lieu of His43, Thr45, Phe48, His125, Thr127, and Arg130. The recombinant ThpR-Ala and wild-type ThpR proteins were purified in parallel by Ni-affinity chromatography, tag-cleavage with Ulp1, and a second Ni-affinity step to remove the His10Smt3 tag. The proteins were tested for RNA CPDase activity under conditions of enzyme excess, by tracking the rate of conversion of RNA>p to RNAp. The results are plotted in Figure 3. Whereas wild-type ThpR hydrolyzed 63% of the RNA>p strand in 1 min, the H43A and T45A mutants were inert up to 30 min. We infer that ribose O3′ coordination by His43 and Thr45 is critical for CPDase activity. The F48A mutation slowed the rate of the CPDase reaction by a factor of 14 under the conditions tested (Fig. 3), implicating the π stack of Phe48 on the terminal nucleobase as important for proper positioning of the terminal nucleotide in the active site. His43, Thr45, and Phe48 are located in strand β3 where they comprise an expanded motif, HxTxxF, that is conserved in Pyrococcus PH0099 (Fig. 2C), Thermus TT0787, and mouse CNPase, but not in Bacillus YjcG, rat AKAP18, human USB1, or Arabidopsis CPDase.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of alanine mutations on CPDase activity. Reaction mixtures (20 µL) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 10 mM EDTA, 20 nM 32P-labeled 10-mer HORNA>p, and 0.2 µM ThpR (wild-type or mutants H43A, T45A, F48A, H125A, T127A, and R130A) were incubated at 37°C for the times specified. The reactions were quenched with formamide, EDTA and the products were analyzed by urea-PAGE. The extents of cyclic phosphate hydrolysis were quantified by scanning the gel with a Fujix imager and are plotted as a function of time. Each datum in the graph is the average of three separate experiments ± SEM.

ThpR mutant H125A was also unreactive with the RNA>p substrate during 30-min incubation (Fig. 3), consistent with the proposed essential role of His125 as general base. However, the T127A mutant displayed vigorous CPDase activity, at the same rate as wild-type ThpR (Fig. 3), signifying that the hydrogen bond of Thr127 with the terminal phosphate is not crucial for CPDase activity. The R130A mutant was inert under the conditions tested, from which we surmise that the arginine contacts to the cyclic phosphate are essential for catalysis. The expanded distal motif, HxTxxR, is conserved in Pyrococcus PH0099 (Fig. 2C) and Thermus TT0787, but not in Bacillus YjcG, rat AKAP18, human USB1, Arabidopsis CPDase, or mouse CNPase.

Concluding remarks

The results presented here shed new light on the structure and biochemistry of E. coli ThpR as an RNA end healing enzyme. The RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase reaction of ThpR yields an RNA 2′-phosphomonoester, signifying that water is the preferred nucleophile for this enzyme when acting on a single-stranded HORNA>p substrate. An RNA 5′-OH is clearly not its obligate nucleophile, notwithstanding that ThpR was originally detected via its ability to direct the reversible transesterification of an RNA 5′-OH to an RNA>p within the context of a broken tRNA stem–loop structure (Fig. 1A; Greer et al. 1983b; Arn and Abelson 1996). Given that ThpR is genetically dispensable in E. coli (Arn and Abelson 1996), we can only speculate as to what use might be made of its CPDase activity. For example, it could act in series with an RNA phosphomonoesterase to completely remove a cyclic phosphate RNA end that might otherwise interfere with RNA 3′-processing by an exonuclease or phosphorylase enzyme. Alternatively, it might perform an end healing step in an RNA repair pathway, by generating a 3′-OH end that can be used by a classic ATP-dependent 3′-OH/5′-PO4 RNA ligase (akin to the role of the 2H CPDases in fungal and plant RNA repair pathways). The problem with the latter idea is that standard laboratory strains of E. coli do not encode a recognizable classic RNA ligase enzyme.

The structure of the ThpR•2′-AMP product complex draws attention to an expanded definition of the catalytic motifs, as HxTxxF48 and HxTxxR130, whereby Phe48 provides a π stacking platform for the terminal RNA nucleobase and Arg130 plays an essential role in catalysis, presumably via transition-state stabilization. The primacy of the dual contacts of Arg130 with the terminal phosphate oxygens likely explains the benign effects of subtracting Thr127, which makes a single hydrogen bond to one of the phosphate oxygens coordinated by Arg130. Indeed, prior studies hinted that the functional importance of the hydroxyamino acid of the distal Hx(T/S) motif can vary among members of the 2H superfamily. To wit, mutating the distal threonine (Thr311) to alanine in mammalian CNPase reduced kcat/Km by >1000-fold (Kozlov et al. 2003). Mammalian CNPase has a cysteine at the position corresponding to Arg130 in ThpR, thereby making it more acutely dependent on the phosphate contacts made by Thr311. In contrast, replacing the serine hydroxyamino acid of the distal HxS motif of yeast ADP-ribose 1″,2″ cyclic phosphodiesterase Cpd1 with alanine had no effect on Cpd1 activity with its physiological substrate Appr>p (Nasr and Filipowicz 2000). Yeast Cdp1 has a tyrosine at the position corresponding to ThpR Arg130. This tyrosine is conserved in the Arabidopsis CPDase ortholog of Cdp1, where it is poised to interact with the scissile phosphate (Hofmann et al. 2000, 2002). Thus, the reliance on a defining motif residue can be overshadowed, or made redundant, by additional contacts to substrate from other moieties that vary among 2H family members.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant EcoThpR

The yadP (hereafter thpR) open reading frame was amplified by PCR from E. coli genomic DNA with primers that introduced a BamHI site at the start codon and an XhoI site 3′ of the stop codon. The PCR product was inserted between the BamHI and XhoI sites of pET28b-His10Smt3 to generate pET-His10Smt3•ThpR, which encodes the full-length ThpR polypeptide fused to an N-terminal His10Smt3 domain. Alanine mutations were introduced into the pET-His10Smt3•ThpR plasmid by quick-change PCR with Pfu DNA polymerase. The inserts were sequenced to exclude the acquisition of unwanted changes during amplification and cloning.

Selenomethionine (SeMet)-substituted ThpR was prepared by transforming pET28-His10Smt3•ThpR into E. coli DE3-B834, a methionine auxotroph. A single transformant was inoculated into 5 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and incubated for 7 h at 37°C. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in 200 mL of complete LeMaster medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. The centrifugation and resuspension steps were repeated twice, after which the cells were resuspended in 200 mL of complete LeMaster medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 50 μg/mL L(+)-SeMet (Acros Organics). The culture was incubated overnight at 37°C with constant shaking, then diluted to A600 of 0.1 in 4 L of fresh LeMaster medium containing kanamycin and SeMet. Growth was continued at 37°C until the A600 reached 0.6. The cultures were chilled on ice for 30 min and then adjusted to 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and 2% (v/v) ethanol. Incubation was continued at 17°C for 16 h with constant shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. All subsequent procedures were performed at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 200 mL buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Triton X-100) and lysozyme was added to 0.2 mg/mL. After 30 min, the lysate was sonicated and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 45 min. The supernatant was mixed for 1 h with 10 mL of His60 Ni Superflow resin (QIAGEN) that had been equilibrated in buffer A. The resin was recovered by centrifugation and washed three times with 75 mL of buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Triton X-100) containing 40 mM imidazole, before a final wash step with 75 mL of Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 3 M KCl. The washed resin was then poured into a column. Bound proteins were eluted with 500 mM imidazole in buffer B. The elution profile was monitored by SDS-PAGE. Peak fractions containing His10Smt3•ThpR were treated with the Smt3-specifc protease Ulp1 (at a His10Smt3•ThpR:Ulp1 ratio of 500:1) during overnight dialysis against buffer B. The dialysate was mixed with 5 mL of His60 Ni Superflow resin that had been equilibrated in buffer B and the mixture was poured into a column. The column was washed with buffer B and bound material was eluted with 500 mM imidazole. The tag-free SeMet-ThpR protein was recovered in the flow-through and wash fractions; the cleaved His10Smt3 tag was bound to the resin and recovered in the imidazole eluate. The SeMet-ThpR preparation was concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration to 4 mg/mL in 4 mL and then gel-filtered through a 120-mL 16/60 HiLoad Superdex-200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer C (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, while collecting 5-mL fractions. The peak SeMet-ThpR fractions were pooled and concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Biorad dye reagent with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Native ThpR and ThpR-Ala mutants were produced by transforming the pET-His10Smt3-ThpR plasmids into E. coli BL21(DE3). Single transformants were grown in LB medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin to a volume of 1 L and A600 of 0.6. The cultures were induced with IPTG and grown overnight at 17°C as described above. The native ThpR proteins were purified from soluble bacterial extracts by Ni-affinity chromatography, tag-cleavage with Ulp1, and a second Ni-affinity step to remove the tag, all as described above for SeMet-ThpR. The second Ni flow-through fractions containing ThpR or ThpR-Ala were dialyzed against 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.05% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol and stored at −80°C.

Crystallization of SeMet-ThpR, diffraction data collection, and structure determination

SeMet-ThpR crystals were grown at 22°C by hanging drop vapor diffusion: 1.5 µL of SeMet-ThpR (5 mg/mL) and 10 mM 2′-AMP (Sigma) were mixed with an equal volume of precipitant solution containing 2 M NaCl and 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8–5.0). Crystals appeared after 1 d and were cryoprotected with precipitant solution containing 25% glycerol before freezing in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction was performed at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 24-ID-C equipped with a Pilatus 6M detector. Diffraction data at 2.02 Å resolution were collected with high redundancy from a single crystal at 0.979 Å (the energy of the K-edge adsorption for selenium) in one sweep of 400 continuous increments of 0.5° each with 0.5-sec exposure per frame. Data from all the images were indexed and integrated using MOSFLM and scaled using SCALA (Winn et al. 2011). The diffraction statistics are compiled in Table 1. The SeMet•ThpR crystals belonged to orthorhombic space group P4212. Substructure solution and initial SAD phase calculations were performed in PHENIX.AUTOSOL (Adams et al. 2002) using diffraction data to 2.5 Å resolution. Four selenium sites were located. Density modification was performed in PHENIX.AUTOSOL assuming two protomers per asymmetric unit and 50% solvent content, after which ∼90% of the amino acids in both the protomers were placed by the auto-build function. The model was adjusted in COOT (Emsley and Cowtan 2004) and subjected to six rounds of refinement in PHENIX using TLS and individual B-factor restraints but without using noncrystallographic symmetry restraints. The model contents and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

Preparation of 3′ 32P-labeled RNA>p substrates

HORNA3′p oligonucleotides labeled with 32P at the penultimate phosphate were prepared by T4 Rnl1-mediated addition of [5′-32P]pCp to a 9-mer or 19-mer synthetic oligoribonucleotide (Tanaka et al. 2011a). The resulting 10-mer or 20-mer HORNA3′p oligonucleotides were treated with E. coli RNA 3′-terminal phosphate cyclase (RtcA) and ATP to generate the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate derivatives, HORNA>p (Tanaka et al. 2011a), which were gel-purified, eluted from an excised gel slice, and recovered by ethanol precipitation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM42498. S.S. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor. We thank Yehuda Goldgur for help with data collection and Ushati Das and Paul Smith for advice on structure refinement.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.046797.114.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. 2002. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D58: 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitsur M, Levitz R, Kaufman G. 1987. Bacteriophage T4 anticodon nuclease, polynucleotide kinase, and RNA ligase reprocess the host lysine tRNA. EMBO J 6: 2499–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arn EA, Abelson JN. 1996. The 2′-5′ RNA ligase of Escherichia coli: purification, cloning, and genomic disruption. J Biol Chem 271: 31145–31153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun PE, Lee J, Gravel M. 2004. 2′,3′-Cyclic nucleotide 3′-phoshodiesterase: structure, biology and function. Myelin Biol Disorders 1: 499–521 [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty AK, Shuman S. 2012. The sequential 2′,3′ cyclic phosphodiesterase and 3′-phosphate/5′-OH ligation steps of the RtcB RNA splicing pathway are GTP-dependent. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 8558–8567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty AK, Subbotin R, Chait BT, Shuman S. 2012. RNA ligase RtcB splices 3′-phosphate and 5′-OH ends via covalent RtcB-(histidinyl)-GMP and polynucleotide-(3′)pp(5′)G intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 6072–6077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das U, Shuman S. 2013. Mechanism of RNA 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate end-healing by T4 polynucleotide kinase-phosphatase. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 355–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. 2004. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YG, Yao M, Okada A, Tanaka I. 2006. The structure of Pyrococcus horikoshii 2′-5′ RNA ligase at 1.94 Å resolution reveals a possible open form with a wider active-site cleft. Acta Crystallogr F62: 1196–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschik P, Hall J, Filipowicz W. 1997. Cloning and characterization of the Arabidopsis cyclic phosphodiesterase which hydrolyzes ADP-ribose 1″,2″-cyclic phosphate and nucleoside 2′,3′-cyclic phosphates. J Biol Chem 272: 13211–13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MG, Smith FD, Scott JD, Barford D. 2008. AKAP18 contains a phosphoesterase domain that binds AMP. J Mol Biol 375: 1329–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer CL, Peebles CL, Gegenheimer P, Abelson J. 1983a. Mechanism of action of a yeast RNA ligase in tRNA splicing. Cell 32: 537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer CL, Javor B, Abelson J. 1983b. RNA ligase in bacteria: formation of a 2′,5′ linkage by an E. coli extract. Cell 33: 899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilcenko C, Simpson PJ, Finch AJ, Bowler FR, Churcher MJ, Lin L, Packman LC, Shlien A, Campbell P, Kirwan M, et al. 2013. Aberrant 3′ oligoadenylation of spliceosomal U6 small nuclear RNA in poikiloderma with neutropenia. Blood 121: 1028–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann A, Zdanov A, Genschik P, Ruvinov S, Filipowicz W, Wlodawer A. 2000. Structure and mechanism of the cyclic phosphodiesterase of Appr>p, a product of the tRNA splicing reaction. EMBO J 19: 6207–6217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann A, Grella M, Botos I, Filipowicz W, Wlodawer A. 2002. Crystal structures of the semireduced and inhibitor bound forms of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 277: 1419–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Kääriäinen S, Rosenström P, Schenkel A. 2008. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics 24: 2780–2781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai A, Sato A, Fukuda Y, Okada K, Matsuda T, Sakamoto T, Muto Y, Yokoyama S, Kawai G, Tomita M. 2009. Characterization of a heat-stable enzyme possessing GTP-dependent RNA ligase activity from a hyperthermophilic archaeaon, Pyrococcus furiosus. RNA 15: 420–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus PA, Dietrich K. 2012. Linking crystallographic model and data quality. Science 336: 1030–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Shirouzu M, Terada T, Yamaguchi H, Murayama K, Sakai H, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S. 2003. Crystal structure of the 2′-5′ RNA ligase from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J Mol Biol 329: 903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Lee J, Elias D, Gravel M, Gutierrez P, Ekiel I, Braun PE, Gehring K. 2003. Structural evidence that brain cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase is a member of the 2H phosphodiesterase superfamily. J Biol Chem 278: 46021–46028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Liu C, Liang YH, Li LF, Su XD. 2008. Crystal structure of B. subtilis YjcG characterizing the YjcG-like group of 2H phosphoesterase family. Proteins 72: 1071–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder R, Iyer LM, Vasudevan S, Aravind L. 2002. Detection of novel members, structure–function analysis and evolutionary classification of the 2H phosphoesterase family. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 5229–5243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllykoski M, Raasakka A, Lehtimäki M, Han H, Kursula I, Kursula P. 2013. Crystallographic analysis of the reaction cycle of 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodesterase, a unique member of the 2H phosphoesterase family. J Mol Biol 425: 4307–4322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasr F, Filipowicz W. 2000. Characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase involved in the metabolism of ADP-ribose 1″,2″-cyclic phosphate. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 1676–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehse PH, Tahirov TH. 2005. Structure of a putative 2′,5′ RNA ligase from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Acta Crystallogr D61: 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus BS, Shuman S. 2013. A kinetic framework for tRNA ligase and enforcement of a 2′-phosphate requirement for ligation highlights the design logic of an RNA repair machine. RNA 19: 659–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus BS, Shuman S. 2014. Distinctive kinetics and substrate specificities of plant and fungal tRNA ligases. RNA 20: 462–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Sawaya R, Ho CK, Shuman S. 2004. Portability and fidelity of RNA-repair systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 2788–2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Aronova A, Ramirez A, Braun P, Shuman S. 2008. Mammalian 2′,3′ cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (CNP) can function as a tRNA splicing enzyme in vivo. RNA 14: 204–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Shuman S. 2011. RtcB is the RNA ligase component of an Escherichia coli RNA repair operon. J Biol Chem 286: 7727–7731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Chakravarty AK, Maughan B, Shuman S. 2011a. A novel mechanism of RNA repair by RtcB via sequential 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesterase and 3′-phosphate/5′-hydroxyl ligation reactions. J Biol Chem 286: 43134–43143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Meineke B, Shuman S. 2011b. RtcB, a novel RNA ligase, can catalyze tRNA splicing and HAC1 mRNA splicing in vivo. J Biol Chem 286: 30253–30257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LK, Schwer B, Englert M, Beier H, Shuman S. 2006. Structure–function analysis of the kinase-CPD domain of yeast tRNA ligase (Trl1) and requirements for complementation of tRNA splicing by a plant Trl1 homolog. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 517–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, et al. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D67: 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Jha BK, Ogden KM, Dong B, Zhao L, Elliott R, Patton JT, Silverman RH, Weiss SR. 2013. Homologous 2′,5′-phosphodiesterases from disparate RNA viruses antagonize antiviral innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 13114–13119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]