Abstract

We previously discovered a small-molecule inducer of cell death, named 1541, that non-covalently self-assembles into chemical fibrils (“chemi-fibrils”) and activates procaspase-3 in vitro. We report here that 1541-induced cell death is caused by the fibrillar, rather than the soluble form of the drug. An shRNA screen reveals that knockdown of genes involved in endocytosis, vesicle trafficking, and lysosomal acidification causes partial 1541 resistance. We confirm the role of these pathways using pharmacological inhibitors. Microscopy shows that the fluorescent chemi-fibrils accumulate in punctae inside cells that partially co-localize with lysosomes. Notably, the chemi-fibrils bind and induce liposome leakage in vitro, suggesting they may do the same in cells. The chemi-fibrils induce extensive proteolysis including caspase substrates, yet modulatory profiling reveals that chemi-fibrils form a distinct class from existing inducers of cell death. The chemi-fibrils share similarities to proteinaceous fibrils and may provide insight into their mechanism of cellular toxicity.

Introduction

Many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with the accumulation of protein fibrils in the brain. These include superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), amyloid-β in Alzheimer's disease, prion protein in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and α-synuclein in Parkinson's disease1. In these disorders, the accumulation of abnormally folded proteins, rich in β-sheets, results in the formation of aggregates that can lead to cytotoxicity. Numerous studies have revealed many important features of these protein misfolding diseases both at the structural and biological levels2. However, the precise cellular mechanisms by which extracellular protein aggregates lead to cellular toxicity remain unresolved.

A high-throughput screen performed in our laboratory identified a small molecule, called 1541 (Fig. 1a), that activates the executioner procaspase-3 in vitro3. The compound induces caspase activation and cell death in various cancer cell lines as fast as the most potent apoptotic inducers known. Compound 1541 (M.W. = 411 Da) and its derivatives induce caspase-3 activation and cell death through a mechanism that is not wholly dependent upon the well-studied intrinsic (caspase-9) or extrinsic (caspase-8) pathways3. Surprisingly, we found that 1541 and other active analogs rapidly self-assemble in aqueous solution into chemical fibrils4 (Fig. 1b); we call them “chemi-fibrils” to distinguish them from natural proteinaceous fibrils. We showed that procaspase-3 localize and become activated on the chemi-fibrils in vitro as well as to proteinaceous amyloid-β fibrils5. Compared to proteinaceous fibrils, 1541 and analogs are remarkably simple to synthesize and form fibrils immediately upon addition to aqueous solution, making them much easier to handle and to study in vitro and in cells.

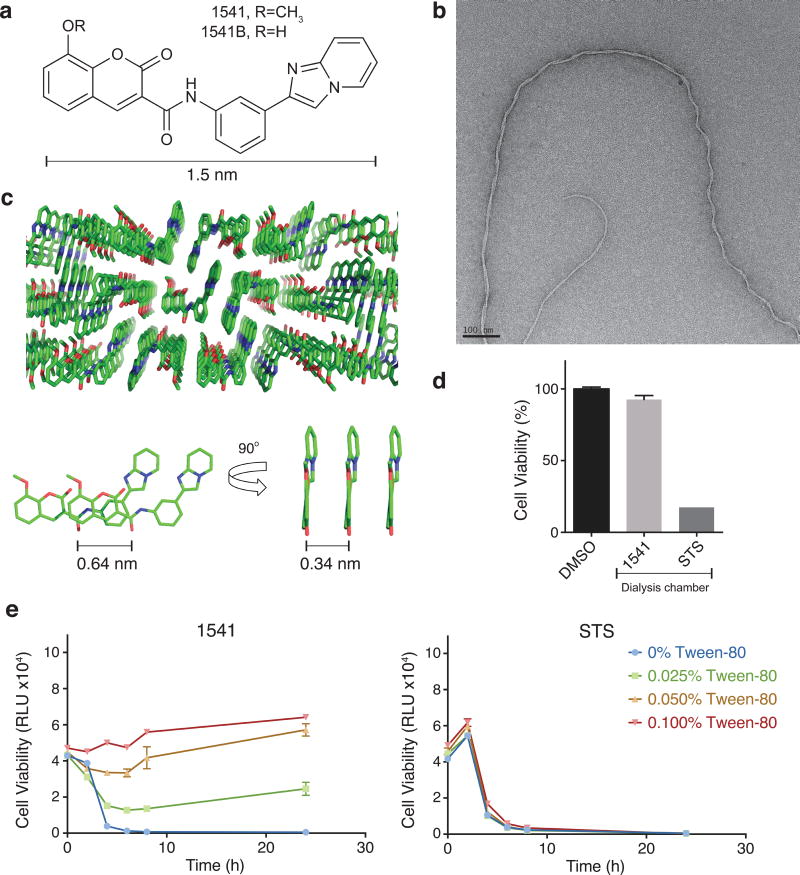

Figure 1. 1541 forms nanofibrils (chemi-fibrils) that induce cell death in cell culture.

(a) Chemical structure of 1541 (R=CH3) and analog 1541B (R=OH). (b) Transmission electron micrographs of the chemical fibrils. (c) Crystal structure of 1541 showing the small-molecule stacking from three different views. (d) Chemi-fibrils induce cell death, but the monomers do not. 1541 or STS were added into a dialysis chamber which was placed into a dish of K562 cells. Cell viability after 24 hours was measured. (e) The non-ionic detergent Tween-80 disrupts 1541 cell-death activity, but has no effect on staurosporine (STS). Cell viability was monitored using CellTiter-Glo (raw luminescence unit). The data represent mean values ± s.d. (n=3).

Here, using various biochemical and biophysical methods, we show that the chemi-fibrils, and not the free soluble small molecule, induce cell death in mammalian culture. We employed diverse methods including shRNA screens6-8, chemical genetic approaches9, N-terminomics to identify proteases involvement10-12, modulatory profiling to help classify their cellular mechanism13, and cell biology tools to show how these enter cells and induce cell death. Remarkably, the chemi-fibrils enter through the endocytic pathway and traffic to lysosomes leading to activation of intracellular proteases, including caspases. We believe these synthetic chemi-fibrils may provide important insights into how extracellular fibrillar structures can induce cell death.

Results

Structural characterization of 1541

Individual molecules of compound 1541 rapidly self-assembles into well-ordered nanofibrils as observed by electron microscopy4 (Fig. 1b). We wished to understand the intermolecular packing of 1541 because unlike protein forming fibrils, 1541 contain very little opportunity for hydrogen bonding. We determined the X-ray structure of 1541 at atomic resolution to reveal the intermolecular interactions between the small molecules, as shown in Figure 1c; crystal data and structure refinement can be found in the Supplementary Results and Supplementary Figure 1. The small molecules are strictly planar and stack on each other with a separation of 0.34 nm. However, each small molecule is shifted by 0.64 nm so that there is no perpendicular ring stacking. Considering that each 1541 molecule is 1.5 nm wide, and that each individual fibril is as thin as 2.6 nm, as observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), it is conceivable that the fibrils may be composed of only two to three 1541 molecules in width. Fiber diffraction studies will be needed to confirm that this packing arrangement is preserved in the chemi-fibrils, as well as to define the fiber axis. Nonetheless, these data show tight packing can be achieved in these chemi-fibrils forming molecules without intricate hydrogen bonding networks typical of proteinaceous fibrils14.

Cell death is induced by the chemi-fibrils not monomers

We have previously shown by TEM and dynamic light scattering (DLS) that the chemi-fibrils of 1541 form within the mixing time when added from DMSO to neutral buffers. The chemi-fibrils also form immediately when transferred from DMSO to cell culture media (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, the threshold concentration for formation of 1541 chemi-fibrils in cell culture (∼2 μM) observed by DLS, matches the approximate EC50 for cell death induced by mammalian cells3. We have shown that once the chemi-fibrils have formed they are apparently kinetically trapped. For example, when a dialysis chamber is placed in a buffer containing 1541 chemi-fibrils, we cannot detect 1541 inside the chamber over a 12 hour period at 37°C (Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, 1541 will not activate procaspase-3 in vitro when the two are separated by a dialysis membrane4. Here, we conduct an analogous experiment to determine if 1541 can induce cell death when partitioned by a dialysis membrane. We utilized the immortalized myelogenous leukemia line K562, which is commonly used in cell death studies. Also, K562 cells conveniently grows readily in suspension and performs well in pooled shRNA screens7. As with other cell lines we have tested, K562 cells are highly sensitive to 1541-induced cell death as monitored by drop in ATP levels and caspase activation (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, when K562 cells are exposed to 1541 sequestered in a dialysis bag (M.W. cutoff of 3.5 kDa) the cells do not undergo cell death over a 48-hour period (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, staurosporine (STS; M.W. 466 Da), a promiscuous protein kinase inhibitor that induces apoptosis in a variety of cell types and that does not form aggregates, causes rapid cell death when cells are exposed directly or isolated behind the dialysis membrane. The same results occurred when cells were placed inside the dialysis bag and the small molecules outside (Supplementary Fig. 6).

One way to perturb small molecule aggregators is to use small amounts of non-ionic detergent in cell culture15. Specifically, Tween-80 is able to dissolve small molecule aggregators and has negligible toxicity in cell culture when dosed less than 0.1% (Supplementary Fig. 7)15. We find that Tween-80 protects cells in a dose dependent manner from 1541 induced cell death (Fig. 1e, left), but does not protect cells from killing by STS (Fig. 1e, right). Tween-80 does not perturb the cellular uptake of 100 nm wide fluorescent nanoparticles16 so these effects are unlikely to be caused by blocking endocytosis. In addition, we found that centrifugation of the 1541-containing cell culture media led to a toxic pellet and a non-toxic supernatant (Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, all our results indicate that 1541 chemi-fibrils induce cell death, as opposed to the 1541 monomer.

shRNA screen reveals genes important for fibril toxicity

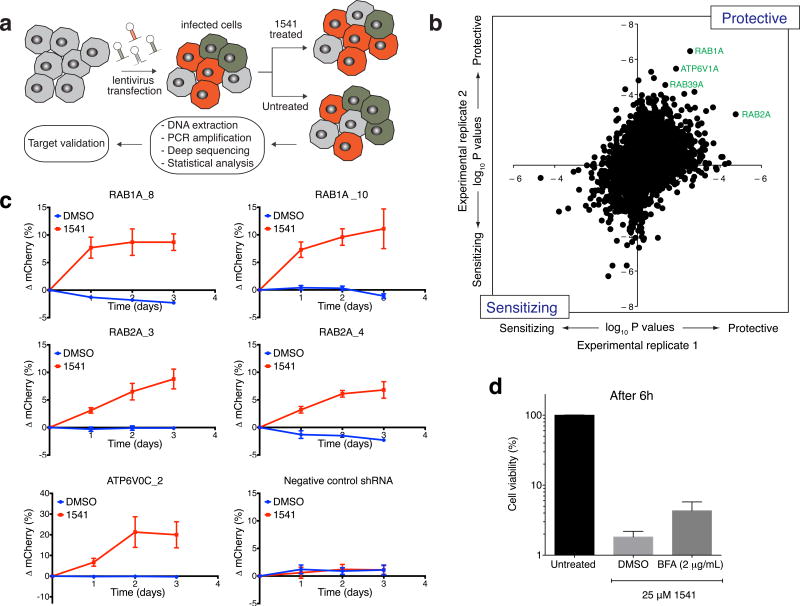

To probe how the chemi-fibrils induce cell death in cell culture, we performed a functional genomic screen using ultracomplex short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) libraries (Fig. 2a). We sought to identify genes that when knocked down would protect or sensitize cells against chemi-fibril-induced apoptosis. K562 cells were transduced using lentiviral shRNA libraries. Together, the sublibraries we used target more than 4,000 genes with 25 shRNAs each, and include more than 500 negative control shRNAs per sublibrary7. Cells were stimulated with compound 1541 (treated) or DMSO (untreated) for 4-5 cycles over 20 days (Supplementary Fig. 9). The cellular DNA was then extracted from the two populations and the shRNA-encoding cassette was PCR amplified. The frequencies of cells expressing each shRNA were quantified in both populations by deep-sequencing and quantitative phenotypes were derived using previously described methodology8. After averaging shRNA phenotypes from two replicate screens, statistically significant protective and sensitizing genes were identified by comparing the phenotypes of shRNAs targeting a given gene to the phenotypes of the negative control shRNAs using the Mann–Whitney U test. We found several strong hit gene, such as RAB1A (Supplementary Fig. 10), for which the vast majority of 25 shRNAs that targeted them protected cells from 1541 toxicity. The top hits are labelled in Figure 2b, showing the good reproducibility between experimental replicates. The full list of genes for the two replicate screens and their p values are presented in Supplementary Dataset 1. Interestingly, we identified several strong hits for genes encoding proteins involved in endocytosis and vesicle trafficking. More specifically, the shRNA screen analysis revealed an important role for the Rab GTPase family in chemi-fibrils induced cell death, including RAB1A, RAB2A, RAB39A, RAB7A, as well as RABEP1 (Supplementary Dataset 1). These small proteins play an important role in vesicle trafficking: RAB1A and RAB2A are particularly important for ER-Golgi transport17, RAB7A has been involved in vesicle trafficking from late endosomes to lysosomes18, RABEP1 is involved in early endosome fusion19, while RAB39A has recently been linked to phagosome acidification20,21 (see ref. 21 for a review). Moreover, we found that V-ATPase, a protein complex essential for acidification of intracellular organelles including lysosomes, also plays an important role in cell death induced by chemi-fibrils.

Figure 2. shRNA screen reveals an important role of vesicle trafficking and lysosome acidification for 1541 chemi-fibrils induced cell death.

(a) Experimental strategy to screen for protective and sensitizing genes against chemi-fibrils. The shRNA screen was performed in two independent duplicates. (b) Protective and sensitizing genes (∼4,000 tested genes) as determined by two-sided Mann–Whitney U test score for sensitization in two independent primary screens. Some of the strongest hits are members of the Rab family of GTPases, regulating steps of vesicle formation and trafficking. (c) Protective effect of knocking-down RAB1A, RAB2A and ATP6V0C genes. Starting at a 50:50 population of wild-type and transfected cells, the population of cells expressing a shRNA (and mCherry) targeting a gene of interest showed important protection against 1541 after 24h-72h of treatment, as monitored by flow cytometry. The error bars represent mean change ± SEM for five independent experiments. (d) Cell viability assay quantifying the protection effect of Brefeldin A (BefA) against chemi-fibril-induced cell death. HeLa cells were treated with BefA for 30 min, and then treated with 25 μM 1541. Cell viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo, and the reported values correspond to mean values ± s.d (n=3). See Supplementary Figure 8 for full dose response of BefA as a function of time, including DMSO and STS controls.

To validate the screening results, we created stable knockdown cell lines expressing single shRNA targeting RAB1A, RAB2A, or the V-ATPase subunit ATP6V0C (Fig. 2c); based on their protective p-values, Rab1A, Rab2A and V-ATPase were ranked #1, #2, and #4, respectively. In these cell lines, the targeted genes were depleted by more than 60% as assessed by real-time PCR (Supplementary Fig. 11). To validate the protective effect of these genes, we mixed equal amounts of wild-type K562 cells and K562 cells expressing a given shRNA (and mCherry) and monitored the phenotype caused by the shRNA as change in the percentage of mCherry-positive cells in the population, as quantified by flow cytometry. As expected, the fraction of cells expressing a protective shRNA targeting RAB1A or RAB2A showed important increase over the wild-type population after chemi-fibrils treatment (Fig. 2c), while the population of cells expressing a control shRNA did not show any change. Consistent with these results, we found that the pre-treatment of HeLa cells with Brefeldin A, an inhibitor of vesicular transport between the ER and the Golgi apparatus, delayed cell death induced by chemi-fibrils (Fig. 2d), but not by STS (Supplementary Fig. 12). To mimic the knockdown of V-ATPase, we found that chloroquine, a lysosomotropic agent, and bafilomycin, an endosomal acidification inhibitor, also weakly protected against 1541 cell death (Supplementary Fig. 13). Together, the shRNA knockdown and pharmacological inhibitor studies suggest intracellular vesicle trafficking and lysosome acidification are important for chemi-fibril-induced cell death.

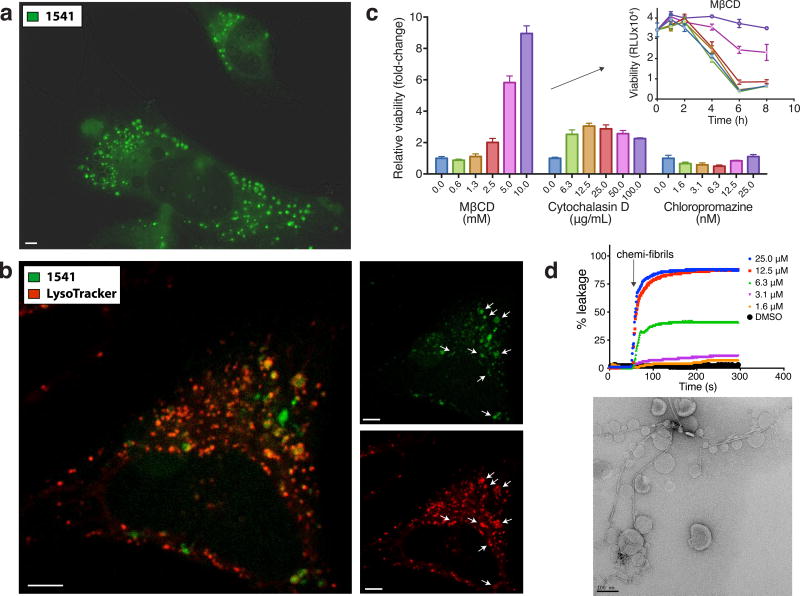

Chemi-fibrils enter cells and traffic to lysosomes

The presence of the coumarin ring in 1541 makes it conveniently fluorescent for microscopy studies (Supplementary Fig. 14). We exploited the fluorescence of 1541 to examine the uptake of chemi-fibrils and their intracellular trafficking. To facilitate analysis by fluorescence microscopy we utilized HeLa cells which are adherent and have a similar sensitivity to 1541-induced cell death as K562 cells15. Prior to cell death, large fluorescent punctae formed within hours of treatment of HeLa cells with 1541 (Fig. 3a). We attribute these fluorescent punctae to 1541 since they were not observed in cells treated with other non-fluorescent cell-death inducers like FasL (Supplementary Fig. 15). To determine the localization of these punctae, we used organelle markers such as ER-Tracker, MitoTracker and LysoTracker (Invitrogen). The fluorescent punctae partially localized with LysoTracker (Fig. 3b), suggesting some localization to lysosomes and/or endosomes, and not with the ER or the mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Fig. 17). We further confirmed the colocalization of fluorescent punctae with lysosomes using HeLa expressing LAMP1-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 18). It is possible that some of the few fluorescent punctae that do not overlap with known organelle markers are present in non-lysosomal vesicles, or correspond to the accumulation of cytosolic chemi-fibrils. Overall, these images support that chemi-fibrils are able to enter mammalian cells, most likely via endocytosis, before inducing cell death.

Figure 3. Internalization of fluorescent aggregates in cell and specific endocytosis inhibition delays cell death.

The presence of a fluorescent coumarin ring in the chemical structure of 1541 (see Fig. 1a) is a convenient way to track chemi-fibrils in live cells. (a) HeLa cells are treated with 1541 and live cell imaging (DAPI channel, shown in green) is used to monitor the accumulation of chemi-fibrils into punctae inside a cell. (b) Lyso-tracker images show partial co-localization to acidic vesicles. Scale bars = 5 μm. (c) Inhibition of endocytosis can partially protect against chemi-fibrils induced cell death after 6 hours of treatment with 20 μM of 1541. MβCD and cytochalasin D delayed cell death by chemi-fibrils, while chloropromazine did not. Cell viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo in triplicate experiments, and the reported protection values correspond to raw luminescence unit (mean values ± s.d.) normalized on cells treated with only 1541 (no inhibitors). (d) Chemi-fibrils induce liposome leakage in vitro (top) and electron microscopy image shows the clear interaction between the chemi-fibrils and liposomes (below). The data is representative of two independent experiments.

Inhibitors of endocytosis partially protect against death

To validate the importance of endocytosis in the 1541 cell death mechanism using an orthogonal approach, we tested specific endocytosis inhibitors (cytochalasin D, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), and chloropromazine) that have previously been used to study the uptake of ALS-causing superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) mutant aggregates22. We discovered that inhibition of certain endocytic pathways could protect cells against chemi-fibril-induced cell death (Fig. 3c). Specifically, MβCD, which disrupts lipid rafts by removing cholesterol from membranes, showed the strongest protective effect. The MβCD was shown by DLS not to disrupt chemi-fibril formation (Supplementary Fig. 19), a distinct possibility since it is known to bind hydrophobic molecules like 1541. The fact that MβCD is not disruptive to 1541 chemi-fibrils is consistent with the very slow dissociation of monomers from the chemi-fibrils. Cytochalasin D, which inhibits actin polymerization, had a small protective effect, and chloropromazine, which disrupts clathrin-dependent endocytosis, had no effect. We did not observe co-localization of 1541 chemi-fibrils with HIV TAT-TAMRA peptides, a common marker of macropinocytosis that colocalizes with SOD114 and tau aggregates14 (Supplementary Fig. 20). These results suggest that chemi-fibrils enter cells using endocytosis to induce cell death.

Chemi-fibrils lead to liposome leakage

Given that chemi-fibrils can directly enter the endocytic pathway, we asked if or how these fibrils may escape vesicles. The release of encapsulated self-quenching carboxyfluorescein from liposomes is commonly used to test the integrity of lipid bilayers23. Various concentrations of 1541 chemi-fibrils were added to carboxyfluorescein-containing liposomes. The addition of chemi-fibrils rapidly caused a large fluorescence increase in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3d) that matched the threshold concentration for fibril formation as monitored by DLS, as well as the EC50 for cell death. Moreover, the chemi-fibrils directly bind liposomes as evidenced by TEM (Fig. 3d). These results indicate that chemi-fibrils are capable of binding lipid vesicles and inducing leakage. Thus, the chemi-fibrils may escape from or cause leakage of endocytic vesicles or downstream compartments, such as lysosomes.

Given the broad activity and unique mechanism for cell death by 1541 we wondered if 1541 would be cytotoxic to microbes as well. Many anti-bacterials kill by puncturing membranes, and 1541 could potentially behave similarly. However, we found 1541 had no impact on growth or survival of yeast, E. coli or B. subtilis (Supplementary Fig. 21).

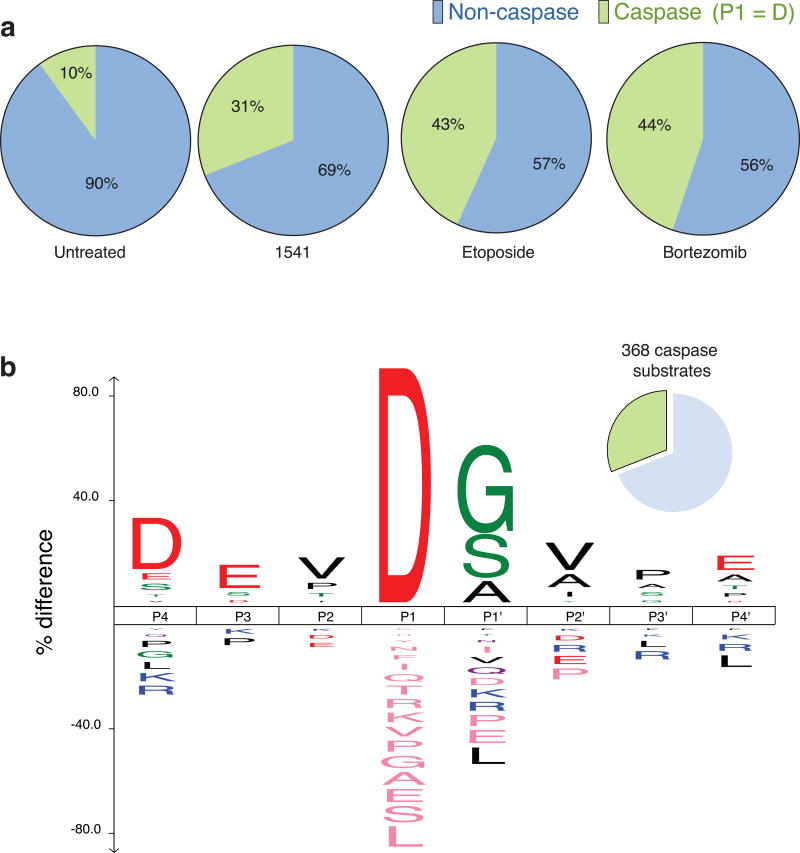

Chemi-fibrils induce widespread proteolysis

Previous studies had shown that 1541-mediated cell death was independent of both typical intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways yet does activate caspases3. We investigated the extent to which 1541 induced proteolysis using a method our lab has developed for identifying the products of intracellular proteases through enzymatic tagging of newly generated N-termini11, called N-terminomics. Using the N-terminomics technology, we determined that cell death induced by chemi-fibrils generates many proteolytic cleavage sites typical of executioner caspases. Nearly 31% (703 of 2980 peptides, 368 of 1187 proteins) of the substrates identified from 1541-treated cells resulted from cleavage after aspartic acid, a hallmark of caspase cleavages (Fig. 4a). These results were generated across two cell lines, HeLa S3 and DB lymphoma cells, and many of the cleaved substrates were found in common with other apoptotic inducers, such as etoposide and bortezomib11,24,25 (http://wellslab.ucsf.edu/degrabase/index.htm)10. Only 10% of these protein substrates were observed in untreated cells, which probably represent a typical small population of dying cells in the cell culture. More than 70% of the substrates found in the chemi-fibrils dataset are identical to those found in cells treated with bortezomib, a stronger inducer of intrinsic apoptosis (Supplementary Dataset 2). Furthermore, the consensus sequence from P4-P4′ for the caspase cleavage sites identified during cell death induced by chemi-fibrils shows the presence of the hallmark DEVD consensus sequence (Fig. 4b), consistent with the activation of executioner caspases. There are many other non-caspase substrates that are generated, suggesting the potential activation of other proteases too. In addition to the activation of caspases and their substrates, we observed important membrane blebbing in HeLa cells upon 1541 treatment using live cell imaging (see Supplementary movie 1 and Supplementary movie 2 online), which is one of the hallmarks of apoptosis. We also observed the formation of very large clumps of cells only a few hours after adding chemi-fibrils to suspension cells (Supplementary Fig. 22).

Figure 4. Cell death induced by chemi-fibrils induces proteolysis with prominent caspase cleavages.

(a) Using our N-terminal labeling technology12, we found 703 peptides containing an aspartic acid at P1 position (out of 2980 peptides). This corresponds to 368 substrates (31% total) having caspase-like cleavage sites plus 819 substrates cleaved by other unidentified proteases. These results were obtained using two independent experiments: one treating HeLa cells with 1541 and one adding 1541B to DB lymphoma cells. In comparison, only 10% of protein substrates can be observed in untreated cells10 (b) Consensus sequence from P4-P4′ for the caspase cleavage sites identified during cell death induced by chemi-fibrils. The figure shows the dominance of a DEVD consensus sequence, supporting the activation of executioner caspases during apoptosis.

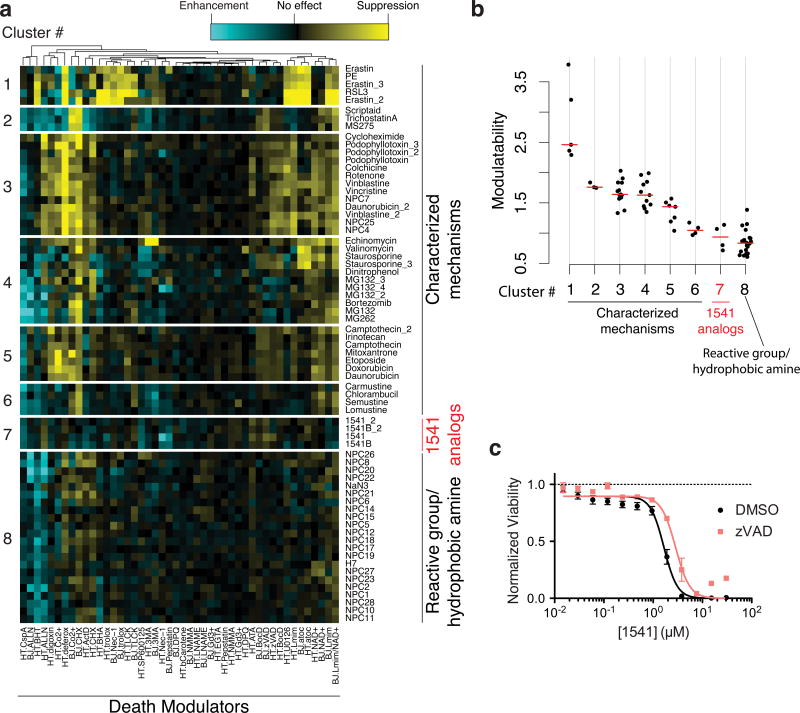

Modulatory profiling suggests an atypical death mechanism

To further compare chemi-fibril-induced cell death to other known cell death inducers, we profiled small molecules for their ability to modulate the lethality of 1541 using a previously described method13. In short, the changes in the lethality of chemi-fibrils when used in combination with each member of a panel of cell death modulators are reported. Model-based clustering26 identified eight distinct clusters and the membership of 71 lethal profiles in these clusters (Fig. 5a). Compound 1541 and its analog (1541B) formed a unique cluster in this analysis. The modulatability scores for 1541 were as low as compounds possessing reactive moieties or hydrophobic amines (Fig. 5b). However, because 1541 and its analog do not contain hydrophobic amines or reactive moieties, and since we found that the lethality of 1541 and its analog could be suppressed by specific shRNAs and vesicle trafficking inhibitors, we conclude that these compounds induce cell death through a distinct mechanism. Interestingly, the pan-caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk, provided only mild protection from 1541-induced cell death (1.7-fold) (Fig. 5c), suggesting 1541 can also induce caspase-independent cell death. From the modulatory profiling experiments, it appears that chemi-fibrils belong to a novel cluster of cell death inducers distinct from those covered by the original modulatory profiles of Wolpaw and colleagues13. This non-covered cluster could potentially include other fibrillar structures not tested like amyloid-β or crystalline substances, such as cholesterol crystals and sodium urate, which are capable of inducing an inflammatory response27,28.

Figure 5. Modulatory profiling suggests 1541 and an analog forms a unique class of compounds that induce cell death only partially delayed by blocking caspases.

The changes in the lethality of chemi-fibrils when used in combination with each member of a panel of cell death modulators are presented. (a) Lethal compounds are clustered based on their “modulatability”, the extent to which their effect is modulated by other molecules. Modulatability values are represented by heatmap colors. Model-based clustering identified eight distinct clusters among 1541 analogs and other characterized lethal compounds. The profiles of all 1541 analogs formed a unique cluster, which suggest their mechanism of cell death is distinct from the other tested compounds. They have a low modulatability overall (i.e. the lethality did not change very much with chemical modulators). (b) Modulatability scores of compounds in eight clusters. Cluster # is the same as in (a). The red bar indicates the median modulatability score of each cluster. The modulatability of 1541 analogs is as small as that of reactive or hydrophobic amines, although their physicochemical properties are distinct from 1541 analogs. (c) Representative dose-curve showing that 1541 analogs are mildly suppressed by pan-caspase inhibitors. The shift in EC50 values for 1541 lethality upon zVAD treatment was 1.7 fold, which was significantly deviated from zero with a probability of 1.5×10-5 (extra sum-of-squares F test). The data represent mean values ± s.e.m. (n=3).

Discussion

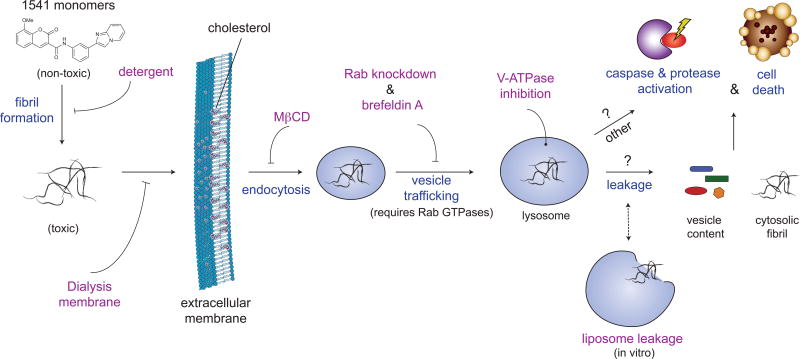

Using a combination of technologies, we have further elucidated the cellular mechanism of 1541-induced cell death and present a working hypothesis that summarizes our data (Fig. 6). We find that 1541 chemi-fibrils form instantaneously in water, buffer solutions or cell culture media. Dialysis, Tween-80, and MβCD protection studies strongly suggest the fibrils, and not the monomer, enter the cell and are responsible for cell killing. In fact, 1541 fibril formation, liposome leakage, and cell death all occur in the same concentration range starting at ∼2-3 μM. Several lines of evidence suggest that the chemi-fibrils enter cells through endocytosis. For example, inhibitors of endocytosis such as Brefeldin A and MβCD restrict 1541-induced cell death, without interfering with fibril formation. We see fluorescent punctae in cells that we attribute to the fluorescent chemi-fibrils accumulating intracellularly, which precedes cell death. We do not observe obvious cell breakage in cell culture, but we do observe membrane blebbing that is typical of apoptosis.

Figure 6. Proposed mechanism of cell death induced by 1541 chemi-fibrils.

The small-molecules forms fibrils in cell culture media. Dialysis or non-ionic detergents can block the cellular entry of chemi-fibrils. Otherwise, the chemi-fibrils enter the cells, as shown by fluorescence microscopy, using endocytic mechanisms, which can be partially blocked by MβCD and brefeldin A. The chemi-fibrils likely traffic within the cells, as shown by shRNA protection experiments, and can localize to lysosomes. They can cause vesicles to leak their content, which could allow the chemi-fibrils and/or the vesicles content to reach the cytosol. The chemi-fibrils result in activation of the caspases and possibly other proteases. The chemi-fibrils can induce a mixed form of cell death, unique from other compounds profiled, that shares some hallmarks of apoptosis such as membrane blebbing.

Our data suggest that the vesicles containing the chemi-fibrils can traffic partly to lysosomes based on their co-localization with acidic vesicles, and not to mitochondria or ER. The shRNA screen identified several genes that when knocked down provided some protection from cell death, including several Rab GTPases important in vesicle trafficking and V-ATPase, an important lysosomal proton pump. We have shown that chemi-fibrils bind to liposomes and induce leakage in vitro, suggesting that the fibrils might be able to escape intracellular vesicles. One possibility is that chemi-fibrils traffic to lysosomes, induce their breakage, and leak their contents. The caspases, among other proteases ultimately become activated, and more than 85% of the observed cleaved products are in common with those described for other apoptotic inducers (Supplementary Dataset 2). Based on the sequence logo of the substrates with non-aspartic acid at P1, some of these unidentified proteases could be cathepsins, trypsin-like proteases, or calpains. The major obstacle in confirming these important proteases is to distinguish meaningful cleavages over background (i.e. untreated cells). Yet, the precise mechanism of cell death appears distinct from other known cell death-inducing small molecules based on comparisons with other toxic compounds using modulatory profiling13. However, much like crystalline substances capable of inducing an inflammatory response in macrophages, such as cholesterol and sodium urate crystals27,28, the chemi-fibrils similarly involve uptake to lysosomes and induce caspase activation that leads to cell death. The chemi-fibrils are more potent than these inflammatory stimuli and induce cell death in mammalian cell lines3 that are not known to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Pan-caspase inhibitors were only mildly protective, and caspases were not strong hits in the shRNA screen. In fact, the protective effects we observed in the shRNA screen were partial, suggesting that none of the 4,000 targets genes are able to completely protect from 1541 cell-death. Our data suggest that there may be parallel cell death mechanisms at work, involving both caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. For example, two uncharacterized GPCR (GPR171 and 174) have been identified as protective hits (see Supplementary Dataset 1). It is possible that an alternate mechanism involving extracellular receptors like GPCRs could play a role here, by regulating endocytosis or by initiating signal transduction.

There are intriguing parallels and differences between these synthetic chemi-fibrils and natural protein amyloid fibrils29, which also form micron-long fibrillar structures. The X-ray structure of crystalline 1541 suggests a tight and dry intermolecular packing of the small molecules, which is much like the steric zipper structures of short protein segments that form fibrils from SOD1, tau and Amyloid-β2. However, intermolecular 1541 interactions lack any of the characteristic hydrogen bonding interactions prominent in the β-sheet structures. It has been shown that amyloid fibrils of mammalian prion proteins are toxic to cultured cells and primary neurons30, and that adding them to cell culture leads to cell aggregation and the formation of cell clumps. Similarly, we observed that formation of very large clumps of cells only a few hours after adding chemi-fibrils to K562 cells. Also, the same small molecules that slow the uptake of fluorescently labeled SOD1 aggregates by human cells22 also protect against chemi-fibrils, suggesting analogous uptake mechanisms. The compound that provided the greatest protection from 1541-induced cell death was MβCD, which has been recently shown to have a protective effect in neuronal cell culture and in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease31. Interestingly, both 1541 fibrils and Aβ-fibrils can activate procaspase-3 in vitro4. Compelling evidence in the neurodegenerative disease field also suggest that small protein oligomers play a major role in neurotoxicity32. This might be the case for chemi-fibrils as well, but more studies will be required to address this complex subject.

Chemi-fibrils may prove to be useful tools to better understand the mechanism of extracellular neurotoxic fibrils, and presents several advantages relative to proteinaceous fibrils. First, the chemi-fibrils form instantly when diluted from DMSO into cell culture and the fibrillar structure is very reproducible. Cell death occurs within a few hours, making chemi-fibrils highly amenable for high-throughput screening to look for inhibitors. Lastly, high yield chemical synthesis provides unlimited material and the potential for detailed structure-activity studies. We believe that our findings, paired with the genetic and pharmacological tools presented, will help future research to better compare the mechanisms for chemi-fibril and proteinaceous fibril induced cell death.

Online Methods

Chemical synthesis and reagents

Synthesis, purification, and characterization of 1541 and related analogs were made as previously described3. Inhibitors were purchased as following and used as is: brefeldein A (Sigma, B5936, >98%), staurosporine (Cayman chemicals, 81590, >98%), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma, C4555), cytochalasin D (Sigma, C2618, >98%), chloropromazine (Sigma, C8138, >98%), chloroquine (Sigma, C6628, >98%), and bafilomycin A1 (Sigma, B1793, >90%).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Chemi-fibrils were generated by diluting DMSO stocks directly into water, buffer, or cell culture media. Solutions were immediately placed on glow-discharged grids (formvar/carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grids from Ted Pella, Inc.) after mixing at room temperature. 1 μL of sample was adsorbed onto the grids for 30 sec. followed by wash in 25 μL water (2×) followed by negative staining in 25 μL drops (×2) of filtered 1% uranyl acetate, pH 7.4. The grids were viewed in a Tecnai T12 electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 120 kV. The images were recorded on a Gatan 4k × 4k CCD camera (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) at 52,000x magnification, unless otherwise specified.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Assays

Particles of 1541 were detected by DLS (Wyatt Technology DynaPro MS/X). The instrument has a 55 mW laser at 826.6 nm, and the laser power was set to 100%, unless otherwise noted. The intensity of scattered light was monitored at an angle of 90°. Again, compound mixtures were prepared in standard assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1% CHAPS) or in water. 1541 was diluted in the buffer from concentrated DMSO stocks and water containing equivalent amount of DMSO was used as control sample to determine the background. Mixtures were analyzed immediately. Each measurement was repeated in triplicate.

Crystallography and structure determination of 1541

Very small pale yellow needle crystals of 1541 were grown by the slow evaporation of a DMF solution at 0°C. Diffraction data were collected using a Bruker D8 platform diffractometer equipped with a Nonius FR-591 rotating-anode Cu source and an APEXII CCD detector. The crystal packing revealed a C2/c space group and a total of 3076 reflections were used for the structure determination. A structural figure with probability ellipsoids is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Cell culture

K562 cells were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% FBS. HeLa cells and 293T cells were grown in DMEM medium with high glucose, further supplemented with glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% FBS. Cells were infected lentivirus-packaged plasmids expressing puromycin resistance, mCherry and an shRNA in a minimal mir30a-context (plasmid backbone pMK1098 for individual shRNA experiments and plasmid backbone pMK1047 for pooled libraries7). For individual shRNA experiments, lentivirus was produced in 6-well plates, and 1 ml viral supernatant adjusted to 8 μg/mL polybrene was used to infect 1×105 cells by spin infection at 1,000 × g for 2 hours at 33°C7. For library infections, virus was produced in 15-cm plates of 293T cells. Library infections were performed on 3.5×107 cells in 70 mL virus supernatant with 8 μg/mL polybrene. Cells were divided into wells of a 6-well plate, and spin-infected as above to get a target multiplicity of infection of ∼30%–40%, as monitored by mCherry expression. This low multiplicitiy of infection was chosen such that most cells would only express one shRNA. Three days after infection, cells were selected with puromycin at 0.7 μg/mL to increase the fraction of infected cells to ∼85%, washed and transferred into fresh medium and allowed to recover for 2 days.

Primary shRNA screen

Design and generation of shRNA libraries in K562 cells was performed as previously described7. Two libraries covering more than 4,000 genes were used in these studies. The shRNA screen was performed in two biological replicates. For both replicates, a population size of at least ∼150 million live cells was maintained at all times, of which ∼85% were infected with an element of the shRNA library, as measured by mCherry fluorescence, to guarantee an average representation of at least ∼1,000 cells per shRNA. K562 cells were treated with 1541 or DMSO for 24 hours, after which the cell culture media was replaced with drug-free medium to let the cells recover during 2-4 days before treating the cells for another cycle. Cell density was re-adjusted to 0.5×106 cells/mL daily and cell growth was monitored using a Scepter cell counter (Millipore) (Supplementary Fig. 7). After more than 20 days of differential growth, 300 million cells were lysed for each the treated and untreated pools and the DNA was extracted. As previously described7, DNA was size-fractionated and the shRNA-encoding cassette was PCR-amplified using primers that introduced Illumina adapters and 4-nucleotide indices. PCR products were gel purified and deep-sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500. Computational analysis was performed using GImap software (gimap.ucsf.edu) as previously described8.

Secondary shRNA validation

shRNAs targeting individual hit genes from the primary screen were cloned into vector pMK10988, in which shRNAs are expressed from an EF1A-promoter driven mRNA also encoding puromycin resistance and the fluorescent protein mCherry. Sequences corresponding to the shRNA guide strands were as follows: RAB1A_8: 5′-TTTAACATTGGACTTCTCAGCA-3′, RAB1A_10: 5′-ATGGAAAGTGACAGACACTGCT-3′, RAB2A_3: 5′-TTATACAAGAATTTGACGGATT-3′, RAB2A_4: 5′-TTATTAATGTCAAAGACTCCT-3′, ATP6V0C_2: 5′-TAAATCATCCGCATACACAGAG-3′, Negative control shRNA: .5′-TTTCTTACTCACCCTAAGAACT-3′.

qPCR

For qPCR, 5×106 cells were collected and RNA was purified using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). 2 ug total of RNA was used for reverse transcription using AMV RT (Roche) and oligo dT. Samples were then quantitated by qPCR using Go-Taq polymerase (Promega) and SYBR green using a LightCycler 480 (Roche).

Cell viability and caspase activity assays

Using one plate per time point, 2 to 5×103 cells are plated into a 96-well plate the day before the experiment for adherent cells, or the same day for K562 or other suspension cell lines. Cell viability was monitored using CellTiter-Glo and DEVDase activity was measured using Caspase-Glo 3/7 (Promega). Detection reagents were added at a 1:1 volume ratio directly into the wells as per manufacturer instructions, and luminescence recorded on a SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices).

Flow cytometry and cellular imaging

Flow cytometry data were obtained on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences) cytometer. The percentages of infected cells were obtained by gating live cells based on forward and side scattering for 10,000 events or more, and mCherry levels were then measured. Live cell imaging was performed on a Nikon Ti-E Microscope wide-field epifluorescence system equipped with a 37°C incubation chamber and CO2 control, or a Zeiss Observer Z1 for shorter experiments. Colocalization experiments with LysoTracker were performed on a Nikon Ti-E Microscope spinning disk confocal. Images were all taken using oil immersion lens with maximum magnification of 63x or 100x in 35 mm No. 1.5 coverslip bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation). Excitation and emission wavelengths of 405 and 460 nm, respectively, were used to monitor 1541. The organelle markers were all purchased from Invitrogen: Hoechst 33342 (H-3570), ER-Tracker Red (E34250) LysoTracker Red (L-7528), MitoTracker Green (M7514). Image processing and analysis was done using ImageJ or Fiji.

Liposomes

Lipid thin films containing 60% DPPC and 40% cholesterol were prepared in 10×25 mm glass test tubes by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure followed by high vacuum for 18 hours. The resultant lipid film was rehydrated in 500 μL of 20 mM HEPES, 20 mM MES buffer containing 100 mM carboxyfluorescein at pH =7.4 (5 mM final concentration). The formulation was then heated to 55°C for 1 hour and sonicated at 55 °C for 15 minutes and extruded through 100 nm polycarbonate membranes to achieve a homogeneous distribution of particles of 100 nm in diameter as determined by Malvern Zetasizer NanoZS. Liposomes were then eluted through Sephadex G-25 resin to remove unencapsulated carboxyfluorescein using an isotonic buffer of 20 mM HEPES, 20 mM MES and 100 mM NaCl. Leakage experiments were performed by monitoring the increase in carboxyfluorescein fluorescence (Ex: 490 nm; Em: 535 nm). Solutions of 1541 were prepared in DMSO and 5 μL of each solution was added directly to the liposomes. Fluorescence was monitored for five minutes and 10 μL of a 1% solution of triton X-100 was added to lyse the liposomes to determine the total carboxyfluorescein present in the sample. Percent leakage was calculated by normalizing the increase in fluorescence over time to the total fluorescence of the sample. For TEM image acquisition, chemi-fibrils (25 μM of 1541) were prepared in water, then liposomes were added to the fibrils, and 1 μL of the mixed solution was placed on a grid as quickly as possible. Staining and data acquisition was performed as described above.

N-terminomics and mass spectrometry

Free N-termini in cells either treated or not treated with 1541 were detected as previously described12. Two independent cellular experiments were carried out. First, HeLa S3 (3×109 cells) were grown in the presence or absence of EGF (100 ng/mL for 10 min), and treated with 25 μM of 1541 fibrils for 16 hours. Cell lysates were collected, free N-termini biotinylated and captured, and on-bead trypsin-digested protein fragments were identified by LC-MS/MS on a QSTAR Elite (AB Sciex). In the second experiment, B lymphoblast (DB) cells were treated with 12.5 μM of 1541B fibrils for 5, 7, 9, 10.5, 12, 16, and 17.5 hours, all in separate dishes containing more than 4×108 cells. Samples were processed as described above. Peptide identification was performed using Protein Prospector (v. 5.6 or higher) (University of California, San Francisco), and all datasets were combined herein. All spectra were searched using the full human SwissProt database (downloaded 2009/12/15 or 2011/07/08) with reverse sequence database for false discovery rate determination. Search parameters included: Fixed modification N-terminal aminobutyric acid and cysteine carbamidomethylation; Variable modifications methionine-loss (N-terminus) and methionine oxidation; up to three missed tryptic cleavages; C-terminal trypsin cleavage; non-specific cleavage N-terminus; parent mass tolerance 100 ppm; fragment mass tolerance 200 ppm. Expectation value cut-off was adjusted to maintain <1% false-discovery rate at the peptide level in each sample.

Modulatory profiling

Chemi-fibrils were examined using modulatory profiling, following the method described previously with a slight modification13. In brief, fibrosarcoma HT-1080 and engineered BJeLR tumor cells were treated with the three compounds in a 14-point, 2-fold dilution series. The highest concentrations used were 1541 (30.4 μM) or the hydroxyl analog 1541B (31.5 μM). The cells were simultaneously treated with a set of cell death modulators13 to produce modulatory profiles. The experiment was done in biological duplicates. The resulting modulators' effects on the lethality of 1541 and its analog, alongside lethal compounds with known mechanism of action, were assessed by computing the difference between area under dose-response curves with or without each modulator treatment. Assembled profiles were analyzed with model-based clustering and visualized in a heatmap. A modulatability score was computed by averaging the absolute values of all the modulators' effects. Computation and visualization were performed using the R statistical language except for Figure 3c. The dose-response curve was generated with GraphPad Prism 5. The significance of difference between EC50 values for two dose-response curves was computed with extra sum-of-squares F test. For the z-VAD-fmk experiment (Fig. 5c), HT-1080 fibrosarcoma or BJeLR engineered fibroblast were seeded into 384 well plates at 1000 cells/well. They were pretreated with 20.9 μg/mL (45 μM) of zVAD-fmk for 1 hour before adding lethal compounds. Cells were incubated for 48 hours. zVAD-fmk was purchased from ENZO (BIOMOL).

Referenced accessions

Crystal structure data for 1541 can be accessed from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC; www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk) and have been allocated accession number CCDC 1009102.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Frances Brodsky, Brian Shoichet, William Degrado, Min Zhuang, Arun Wiita, Zachary Hill, JT Koerber, Nathan Thomsen, Joel Watts, Sue-Ann Mok and Justin Rettenmaier for insightful discussions and/or critical reading of the manuscript. A special thanks to Yuwen Chen (cell culture and laboratory practices expertise), Yifan Cheng and Michael Braunfield (EM), Allison Doak (DLS), Hai Tran (yeast expertise), Delaine Larsen (live cell imaging), Jessica Lund (deep-sequencing), Mike Hornsby and Klim Verba (fluorescence), and Tet Matsuguchi (qPCR) for technical help. Brent R. Stockwell is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA136779 (to J.A.W.), R01 CA097061 (to B.R.S.) and F32AI095062 (to V.J.V.). J.A.Z. received an ARCS Foundation Award and a Schleroderma Research Foundation Evnin-Wright Fellowship. M.K. was supported by a postdoctoral Fellowship from the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund. O.J. is the recipient of a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Government of Canada.O.J. and M.K. received a Fellowship/grant from the UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, which is funded in part by the Sandler Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: O.J. performed the cell culture experiments, electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering, flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy under J.A.W. supervision. O.J. performed the shRNA screen and made the stable cell lines, with help and guidance of M.K. and M.B. supervised by J.S.W.; M.K. analyzed the deep-sequencing data. J.A.Z. synthesized the 1541 analogs and provided general expertise on the project. A.L.R. performed the crystallography and structure determination. V.J.V. performed the liposome leakage assays. K. Shimbo and N.J.A. performed the degradomics experiments, and O.J. compiled the results. K. Shimada performed the modulatory profiling experiments under B.R.S. supervision. O.J. and J.A.W. wrote the manuscript with contributions from M.K., J.A.Z, and B.R.S, and input from all authors.

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jucker M, Walker LC. Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2013;501:45–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg D, Jucker M. The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases. Cell. 2012;148:1188–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolan DW, Zorn JA, Gray DC, Wells JA. Small-molecule activators of a proenzyme. Science. 2009;326:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1177585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zorn JA, Wille H, Wolan DW, Wells JA. Self-assembling small molecules form nanofibrils that bind procaspase-3 to promote activation. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19630–19633. doi: 10.1021/ja208350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zorn JA, Wolan DW, Agard NJ, Wells JA. Fibrils colocalize caspase-3 with procaspase-3 to foster maturation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33781–33795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassik MC, et al. Rapid creation and quantitative monitoring of high coverage shRNA l ibraries. Nat Methods. 2009;6:443–445. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassik MC, et al. A systematic Mammalian genetic interaction map reveals pathways underlying ricin susceptibility. Cell. 2013;152:909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampmann M, Bassik MC, Weissman JS. Integrated platform for genome-wide screening and construction of high-density genetic interaction maps in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2317–E2326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss WA, Taylor SS, Shokat KM. Recognizing and exploiting differences between RNAi and small-molecule inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1207-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford ED, et al. The DegraBase: a database of proteolysis in healthy and apoptotic human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:813–824. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.024372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahrus S, et al. Global sequencing of proteolytic cleavage sites in apoptosis by specific labeling of protein N termini. Cell. 2008;134:866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiita AP, Seaman JE, Wells JA. Global analysis of cellular proteolysis by selective enzymatic labeling of protein N-termini. Methods Enzymol. 2014;544:327–358. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417158-9.00013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolpaw AJ, et al. Modulatory profiling identifies mechanisms of small molecule-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E771–E780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106149108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes BB, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3138–E3147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301440110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen SC, Doak AK, Wassam P, Shoichet MS, Shoichet BK. Colloidal aggregation affects the efficacy of anticancer drugs in cell culture. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1429–1435. doi: 10.1021/cb300189b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen SC, et al. Colloidal Drug Formulations Can Explain “Bell-Shaped” Concentration-Response Curves. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:777–784. doi: 10.1021/cb4007584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tisdale EJ, Bourne JR, Khosravi-Far R, Der CJ, Balch WE. GTP-binding mutants of rab1 and rab2 are potent inhibitors of vesicular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:749–761. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucci C, Thomsen P, Nicoziani P, McCarthy J, van Deurs B. Rab7: a key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenmark H, Vitale G, Ullrich O, Zerial M. Rabaptin-5 is a direct effector of the small GTPase Rab5 in endocytic membrane fusion. Cell. 1995;83:423–432. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seto S, Tsujimura K, Koide Y. Rab GTPases Regulating Phagosome Maturation Are Differentially Recruited to Mycobacterial Phagosomes. Traffic. 2011;12:407–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Münch C, O'Brien J, Bertolotti A. Prion-like propagation of mutant superoxide dismutase-1 misfolding in neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3548–3553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein JN, Yoshikami S, Henkart P, Blumenthal R, Hagins WA. Liposome-cell interaction: transfer and intracellular release of a trapped fluorescent marker. Science. 1977;195:489–492. doi: 10.1126/science.835007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimbo K, et al. Quantitative profiling of caspase-cleaved substrates reveals different drug-induced and cell-type patterns in apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12432–12437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208616109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiita AP, et al. Global cellular response to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Elife. 2013;2:e01236. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraley C, Raftery AE. Model-based clustering, discriminant analysis, and density estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 2002;97:611–631. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duewell P, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halle A, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huff ME, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Pathological and functional amyloid formation orchestrated by the secretory pathway. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novitskaya V, Bocharova OV, Bronstein I, Baskakov IV. Amyloid fibrils of mammalian prion protein are highly toxic to cultured cells and primary neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13828–13836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao J, et al. Neuroprotection by cyclodextrin in cell and mouse models of Alzheimer disease. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2501–2513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.