Abstract

Objective

Otitis media (OM) in children is the most frequent reason for physician visits in developed countries and burdens caregivers, society, and the child. Our objective was to describe the impact of OM severity on parent/caregiver quality of life (QoL).

Study Design

Multi-institutional prospective cross-sectional study.

Setting

Otolaryngology, family, and pediatric practices.

Subjects and Methods

Children 6 to 24 months old with and without a primary diagnosis of recurrent OM and their caregivers. Physicians provided patient history, and parents/caregivers completed a Family Information Form, the PedsQL Family Impact survey, the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) survey, and the OM 6-item severity survey (OM-6).

Results

A total of 2413 subjects were enrolled and data from 1208 patients and physician were analyzed. The average child age was 16 months, and 54% were male. The mean OM-6 score was 3.2. The mean PedsQL Family Impact score for parents was 66.9 from otolaryngology sites and 78.8 from pediatrics/family practice sites (P <.001). Higher (worse) OM-6 scores correlated significantly with worse PedsQL Family Impact scores (Pearson r = −0.512, P <.01). Similarly, increasing OM-6 scores strongly correlated with increased parental anxiety, depression, and fatigue, as well as decreased satisfaction (all P <.01).

Conclusions

Worse PedsQL Family Impact and PROMIS scores were highly correlated with elevated OM-6 scores, suggesting that severity of childhood OM significantly affects parent/caregiver QoL. Understanding the impact of a child’s illness on parent/caregiver QoL can help physicians counsel patients and families and provide better family-centered, compassionate care.

Keywords: OM, quality of life, tympanostomy tube, pressure equalization tube, caregiver

Otitis media (OM) is the most frequent reason for physician visits, antibiotic use, and surgery for children in developed countries. Up to 40% of children will experience recurrent OM (defined as ≥3 distinct episodes in 6 months or ≥4 episodes in 12 months).1 Most children have at least 1 episode of acute OM by age 3 years, with the incidence peaking between 6 and 11 months of age.2 Since children with OM often have sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, and earache, as well as psychosocial and behavioral problems, parents/caregivers (“caregivers”) may also have decreased quality of life (QoL). When caring for a child with OM, caregivers may miss work, pay extra childcare expenses, and experience increased stress and anxiety at home and work.3 Research suggests that not only does recurrent OM negatively affect caregiver QoL, but it also negatively affects a caregiver’s perception of his or her child’s QoL in relation to the disease.1 Thus, it is likely that there is a compound effect on health care costs and utilization driven not only by the child’s OM but also the distress that caregivers experience related to their child’s illness.

Our study explored the impact that children with OM, aged 6 to 24 months, has on the family and caregivers. Using a series of validated surveys distributed to caregivers of children with OM, we explored the impact and predictability of OM severity on caregiver QoL. We hypothesized that the greater the severity of OM in children, the poorer the QoL of their caregivers. In addition, we explored the possibility that caregiver perception of the severity of illness in a child may drive parents to seek out specialists and potentially different treatment options, such as tympanostomy tube placement.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a multi-institutional prospective cross-sectional study conducted at 23 participating sites, including family practice, pediatrics, and otolaryngology (Peds Oto) clinics. The sites were recruited through the BEST-ENT (Building Evidence for Successful Treatments in Otolaryngology) and CHEER (Creating Healthcare Excellence through Education and Research) research networks. Participating sites recruited interested caregivers of the eligible patients at the time they were seen between January 2009 and February 2012. Inclusion criteria at the participating otolaryngology site were children aged 6 to 24 months who presented with a chief complaint of OM. The lone inclusion criterion at a participating family practice or pediatric site (PCP) was children aged 6 to 24 months who presented for routine well-child visits and immunization, regardless of history of OM. The patients recruited from pediatrics and family practice sites came to the clinic for well-child visits and served as normal well-child controls. We oversampled for patients presenting to an otolaryngology practice, with the intent of obtaining as many children from the most severely affected end of the spectrum of OM severity as from the less affected end of the spectrum. Exclusion criteria were (1) children younger than 6 months or older than 24 months, (2) caregivers who were unable to provide consent, and (3) caregivers who were unable to complete the survey forms in English.

Caregivers who chose to participate were given a packet of surveys to complete either during their visit or later with a mail-in option. We obtained an institutional review board waiver of written informed consent for caregivers from the Washington University Medical Center Human Research Protection Office, and we obtained written informed consent from participating physicians.

Background Data

Demographics and an overall health and OM history form were provided by the caregiver. Collected information included family income; parental insurance status and educational level; number of adults and children in the household; age, sex, and ethnicity of the child; daycare attendance status; and parental reports on the number of OM episodes and the perceived problems resulting from these episodes. Physician-provided information included assessment of the child’s current condition, number of visits in the past 3 months with a diagnosis of ear infections or middle ear fluid, hearing level, comorbidities, number of sets of ear tubes, and candidacy for tube placement. Physicians also filled out a practice profile form once at the start of the study.

Outcomes Assessed

Validated surveys were used to assess QoL of children and their caregivers. The OM-6 survey is a 6-item, disease-specific questionnaire that is a valid and reliable measure of QoL of children with OM. It represents the domains of physical suffering, hearing loss, speech impairment, emotional distress, activity limitations, and caregiver concerns.4 Caregivers serve as proxy to answer questions regarding their perception of the child’s functional health status. Scores can range from 1 to 7. Higher OM-6 scores indicate increased severity and impact of OM on the child resulting in decreased disease-specific QoL.4

The PedsQL Family Impact Module measures the impact of pediatric health conditions on caregivers and family. Domains of physical, emotional, social functioning, cognitive functioning, communication, worry, daily activities, and relationships are measured. Scores can range from 0 to 100. A lower Family Impact score correlates with poorer QoL.5

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) individual item response questions were selected to assess the QoL impact of a child’s health on the adult caregiver, with respect to anxiety, fatigue, depression, and satisfaction.6 The PROMIS tool is generalizable to all adults, whereas the PedsQL Family Impact module focuses on the QoL of parents and caregivers specifically. By using both, we aimed to understand the impact on a scale that is generalizable to a broader population. The PROMIS raw scores were converted into t scores, where higher PROMIS t scores indicated poorer reported levels of anxiety, fatigue, and depression. For the category of satisfaction, a lower t score indicated worse reported satisfaction.6

Statistical Analysis

Scores for OM-6 were correlated to the impact on caregiver QoL (both PedsQL Family Impact and PROMIS scores). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 (SPSS, Inc, an IBM Company, Chicago, Illinois). Bivariate analysis was performed using the independent Student t test for dichotomous predictor variables, analysis of variance (ANOVA) for categorical predictor variables (using Tukey’s honestly significant difference for post hoc testing), and Pearson’s correlation for continuous predictor variables. Multivariable analysis was performed using linear regression modeling. Statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed a level of 0.05.

Results

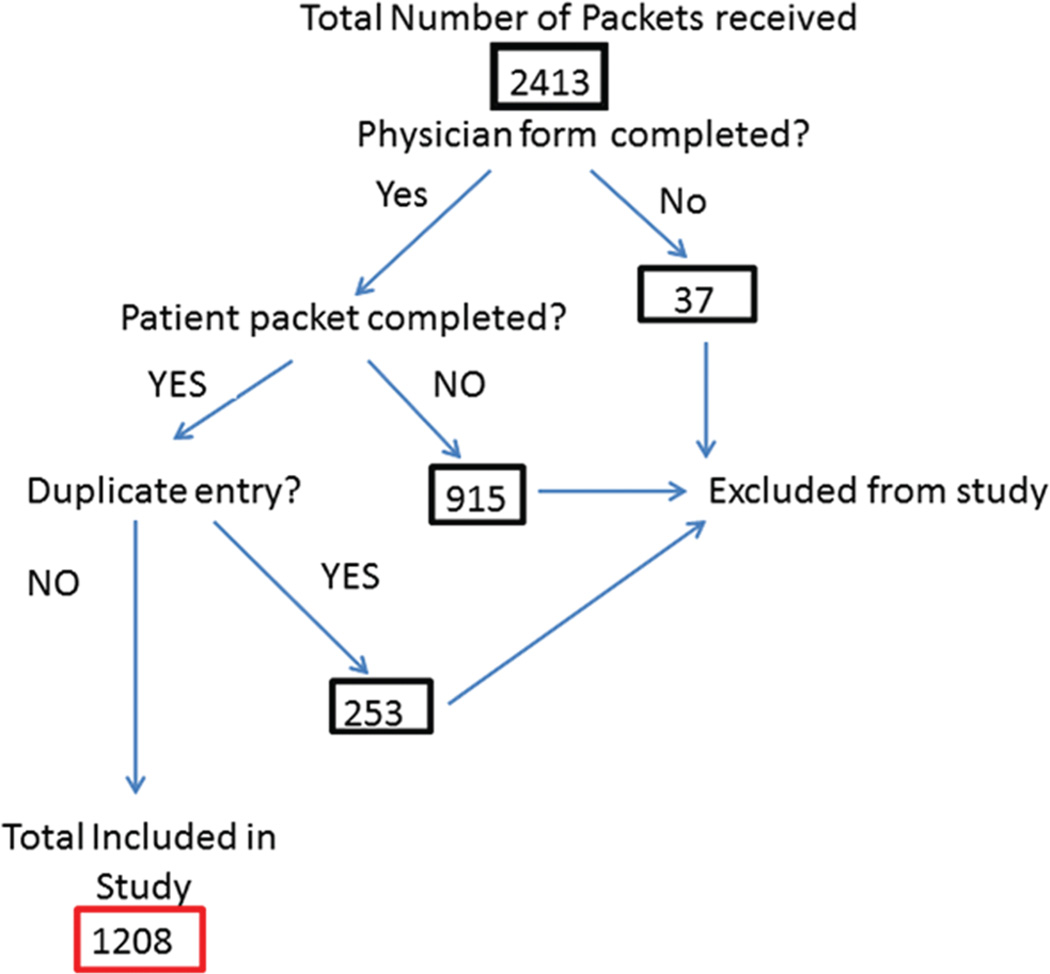

Study personnel distributed 2413 survey packets. After performing data quality checks, we excluded from analysis surveys that represented duplicate entries or that were missing a completed physician form, a completed patient survey packet, or both. Data for 1208 children were used in our analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included patients.

Demographics

The average age of participants was 14.7 months, and 54% were male. Of the patients, 83% were enrolled by otolaryngology practices, and 15% were enrolled by either family practice or pediatrics clinics. Two percent of participants were not linked to a particular site ID. Additional demographics of the study population can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of Children and Caregivers.a

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Child’s age, mean (SD), mo | 14.7 (4.5) |

| Child’s sex | |

| Male | 652 (54.0) |

| Female | 556 (46.0) |

| Child’s race | |

| White | 1004 (86.2) |

| Black or African American | 104 (8.9) |

| Asian | 12 (1.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (0.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 41 (3.5) |

| Total | 1165 (100) |

| Child’s ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 55 (6.0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 863 (94.0) |

| Total | 918 (100) |

| Educational level of mother | |

| 7th–9th grade or less | 2 (0.2) |

| 9th–12th grade | 34 (2.9) |

| High school graduate | 97 (8.3) |

| Some college or certificate course | 328 (27.9) |

| College graduate | 414 (35.2) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 299 (25.5) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.1) |

| Total | 1175 (100) |

| Household income | |

| <$20,000 | 160 (14.0) |

| $20,000–39,999 | 172 (15.1) |

| $40,000–59,999 | 136 (11.9) |

| $60,000–79,999 | 198 (17.3) |

| $80,000–99,999 | 172 (15.1) |

| $100,000 or higher | 300 (26.3) |

| Other | 3 (0.3) |

| Total | 1141 (100) |

| Child’s insurance status | |

| None | 3 (0.3) |

| Medicaid | 300 (25.8) |

| Private or employer sponsored | 796 (68.5) |

| Other government insurance | 63 (5.4) |

| Total | 1162 (100) |

Values are presented as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Correlation of OM-6 with Parental QoL

For our entire study population, the mean (SD) OM-6 score was 3.2 (1.3). As Table 2 shows, the mean OM-6 score for patients enrolled by otolaryngologists was significantly worse than the OM-6 for those seen at primary care clinics. The overall mean (SD) PedsQL Family Impact Score in our study was 68.7 (18.9). The mean PedsQL Family Impact Score for caregivers of children seen at otolaryngology practices was significantly worse than that for caregivers of children seen at a PCP. The mean PROMIS scores for anxiety, fatigue, depression, and satisfaction were all significantly worse for caregivers of children seen by otolaryngologists than for those seen by a PCP. Among the children whose clinic site could not be linked, the scores qualitatively appear to be similar to otolaryngology sites.

Table 2.

Child Severity of Disease (OM-6) and Quality-of-Life Scores for Caregivers (PROMIS and PedsQL Family Impact) of Children Seen by Otolaryngology (Peds Oto) vs Primary Care (PCP) Clinicians.

| Quality-of-Life Measure | Overall (n = 1208) |

Peds Oto (n = 1001 [82.9%]) |

PCP (n = 184 [15.2%]) |

Unknown (n = 23 [1.9%]) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMIS—parental proxy, mean (SD) | |||||

| Anxiety | 52.1 (10.2) | 53.2 (9.8) | 45.9 (9.9) | 54.0 (10.5) | <.001 |

| Fatigue | 52.8 (9.7) | 53.6 (9.5) | 47.9 (10.0) | 53.8 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Depression | 46.6 (9.3) | 47.3 (9.4) | 42.8 (7.9) | 44.9 (8.3) | <.001 |

| Satisfaction | 50.3 (8.6) | 50.0 (8.5) | 51.6 (9.5) | 49.4 (7.2) | .090 |

| PedsQL Family Impact, mean (SD) | 68.7 (18.9) | 66.9 (18.4) | 78.8 (18.7) | 69.2 (16.1) | <.001 |

| OM-6, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.0) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: OM-6, otitis media 6-item severity survey; PROMIS, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Worse OM-6 scores were moderately correlated with poorer PedsQL Family Impact scores (Pearson’s r = −0.51, P <.01). Similarly, more severe OM-6 scores were correlated with increased caregiver anxiety, fatigue, and depression, as well as decreased satisfaction. PedsQL Family Impact scores were moderately to strongly correlated with caregiver reported anxiety, fatigue, depression, and satisfaction (Pearson’s r −0.70, −0.73, −0.71, and 0.53, respectively). All correlations were statistically significant (P < .001).

OM-6 and Caregiver QoL vs Physician Tube Recommendation

We analyzed reported severity of OM as well as caregiver QoL compared with the status of the physician’s recommendation for tube placement. There were 1167 responses to the question on the presence or absence of tubes. A total of 194 of 1167 (16.6%) patients had tubes in place. Providers recommended tube placement in 252 of 464 (54.3%) patients aged 6 to 12 months and in 382 of 567 (67.4%) patients aged 13 to 24 months. Because primary care physicians made recommendations for tube placement in only 3 patients aged 6 to 12 months and 6 patients aged 13 to 24 months, we did not analyze them separately. As summarized in Table 3, mean OM-6 and PedsQL Family Impact scores for children in whom ear tubes were recommended were significantly worse than for children in whom tubes were not recommended and in children who already had tubes placed (P <.001). Mean PROMIS t scores for parental anxiety, fatigue, and depression were all significantly worse for parents of children in whom ear tubes were recommended by a physician than for those in whom tubes were not recommended and in children who already had tubes.

Table 3.

Child Severity of Disease (OM-6 Score) and Caregiver Quality-of-Life (PROMIS and PedsQL Family Impact) Mean Scores Based on Tube Recommendation Status (n = 1167).

| Tube Recommendation Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Child Already Has Tubes | P Value | |

| PROMIS—parental proxy, mean (SD) | ||||

| Anxiety | 54.9 (9.6) | 46.5 (9.3) | 50.8 (10.2) | <.001 |

| Fatigue | 55.0 (9.0) | 47.8 (9.4) | 51.8 (9.8) | <.001 |

| Depression | 48.3 (9.5) | 43.1 (7.7) | 46.3 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Satisfaction | 49.3 (8.5) | 51.9 (8.8) | 51.0 (8.8) | <.001 |

| PedsQL Family Impact, mean (SD) | 64.1 (18.2) | 78.4 (17.4) | 68.8 (19.1) | <.001 |

| OM-6, mean (SD) | 3.6 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: OM-6, otitis media 6-item severity survey; PROMIS, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Multivariable analyses were performed to further confirm our findings. Simple linear regression showed that OM-6 alone explained 26% of the variance in PedsQL Family Impact scores. In the multiple linear regression model shown in Table 4, however, the caregiver PROMIS scores for anxiety, fatigue, and depression explained 65.5% of the variance in Family Impact scores, and child severity of disease, as measured by OM-6, added only 1% of variance.

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Showing the Cumulative Percent Variance of PedsQL Family Impact Scores Explained by Caregiver Anxiety, Fatigue, and Depression (Measured by NIH PROMIS Items) and Burden of Otitis Media on Health Care–Related Quality of Life in the Child (Measured by OM-6).

| Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | t value | P value | Cumulative Percent Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 156.8 | 2.17 | 72.30 | <.001 | |

| Anxiety | −0.33 | 0.0452 | −6.34 | <.001 | 45.4 |

| Fatigue | −0.67 | 0.050 | −13.4 | <.001 | 60.2 |

| Depression | −0.66 | 0.054 | −12.30 | <.001 | 65.5 |

| OM-6 | −1.77 | 0.32 | −5.46 | <.001 | 66.5 |

Abbreviations: NIH, National Institutes of Health; OM-6, otitis media 6-item survey; PROMIS, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Discussion

Caregiver QoL is strongly associated with the burden of OM disease in a child, as well as by a physician’s recommendation for tympanostomy tubes. Our study examined these effects while allowing for comparison between caregivers of children with OM evaluated at an otolaryngology practice and those at a family or pediatric practice.

Elevated OM-6 scores, a proxy for evaluating the impact of OM on children, correlated with poorer overall caregiver QoL, as determined by PedsQL Family Impact scores. The mean PedsQL Family Impact score for our study was worse than the reported mean in the literature of 81.0 for parents of children with chronic disease in a convalescent hospital.5 In addition, higher OM-6 scores were correlated with increased caregiver anxiety, depression, and fatigue, as well as decreased satisfaction. Similar to prior studies, these results imply that the QoL burden of OM, not just the presence of disease, is an important factor in caregiver QoL.7, 8 Caregiver QoL was directly correlated with caregiver levels of anxiety, depression, and fatigue and inversely correlated with caregiver satisfaction.

Not surprisingly, otolaryngology practices saw patients with a significantly higher burden of OM disease as reported by caregivers, as well as significantly poorer caregiver QoL as determined by the PedsQL Family Impact scores. This suggests that otolaryngologists appropriately evaluate and treat patients who experience greater disease impact, since caregiver QoL was significantly correlated with OM-6 scores. In addition, parental anxiety, depression, and fatigue are much higher in caregivers whose children were evaluated by an otolaryngology practice. This suggests that parents with children with a more severe impact on QoL have higher levels of anxiety, depression, and fatigue and that perhaps these parents are more likely to seek referral to a specialist. However, these associations do not imply causality, that either higher burden of OM disease or higher parental anxiety, depression, or fatigue is the driving factor for seeking subspecialty care.

A physician recommendation for the placement of tubes was significantly associated with greater impact of OM on the child and poorer QoL of caregivers. The PedsQL Family Impact scores were best for caregivers of those children in whom a physician did not recommend ear tubes at all, followed by those children who already had ear tubes. They were worst for caregivers of children in whom ear tubes were recommended by a physician. PROMIS scores of anxiety, fatigue, and depression were similarly worse for caregivers of children in whom ear tubes were recommended. This shows that increased impact of OM on the child, which would lead a physician to recommend ear tubes, is associated with worse caregiver QoL. Eligibility for ear tubes may be more of a factor in driving caregiver QoL than is the actual placement of ear tubes.

The mean PROMIS t scores for parental satisfaction for parents of children in whom tubes were recommended were also statistically significantly worse than for those in whom tubes were not recommended and in children who already had tubes; however, these means were very tightly clustered and do not represent clinically important differences. The PROMIS domain of satisfaction is related to the adults’ satisfaction in their ability to continue performing daily routines and caring for their family. This suggests that while caregivers of children with a severe burden of OM can still be functional in their activities of daily living, their QoL as related to anxiety, fatigue, and depression is diminished.

Our findings suggest that parental QoL, including levels of anxiety, fatigue, and depression, are strongly influenced by caregivers’ perception of the severity of their child’s illness. Caregivers’ understanding of their child’s illness may be affected not only by objective measures of the severity of illness or child QoL but also the referral to a specialist, as well as a specialist’s recommendation for pressure equalization tubes. It is also possible that because of this poor QoL, caregivers seek referral to specialists and the placement of pressure equalization tubes, even when the recommendations for tube placement are becoming more conservative. The most recent practice guidelines for tympanostomy tube placement, released by the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) in July 2013, have become more restrictive in which patients are offered tubes than in previous years. Particularly, the recommendations state that clinicians should not offer tympanostomy tube placement to children with recurrent acute OM who do not have an effusion in either ear at the time of tube candidacy assessment.9

One of the major limitations of our study is that it was a cross-sectional study. Because of this, we could not evaluate the changes in QoL for the individual child and family before and after placement of ear tubes. It is possible, based on clinical experience, that there is a larger difference in QoL than we observed in this study, as suggested by an earlier study; however, we cannot confirm the anticipated size of improvement in QoL with this study design.10 A longitudinal observational study is needed to look at the change in QoL before and after tube placement in children with OM.

The survey method and cross-sectional design of this study further limited the independent confirmation of the diagnosis of OM, number of OM episodes, and severity of the burden of disease for the children in this study. Caregiver perception of the number of episodes of OM tends to be significantly higher than the number of episodes diagnosed by physicians.11, 12 Furthermore, overdiagnosis of acute OM is thought to be common, due to the difficulty with examining an uncooperative child, distinguishing between acute OM and otitis media with effusion, and varying criteria used to define OM.13 Nevertheless, the child’s burden of OM correlated well with caregiver QOL, and thus the results supported our initial hypothesis.

Another limitation is that we do not know if the practitioners in the study followed the AAO-HNS guidelines for recommendation of tympanostomy tube placement. Medical decision making can be influenced by parental concerns and anxiety, and it is possible that parental concerns and perceptions of their child’s illness are stronger driving forces in the decision to place ear tubes than the actual severity of a child’s illness.

The present study gathered information from a large number of children with a broad range of impact from OM from many sites across the United States. The population was not limited to healthy children but included a number of children with medical problems. This is likely to be representative of a broad cross section of patients who present to otolaryngology offices. Well-validated adult and child surveys were used to gather data, and the outcomes correlate with expectations of the effects of OM on caregiver QoL. Understanding the impact of a child’s illness on caregiver QoL can help physicians counsel patients and families and provide better family-centered, compassionate care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following clinics and medical centers for their assistance with patient enrollment and recruitment: Washington University School of Medicine; Coastal Ear, Nose and Throat; Otolaryngology Consultants of Memphis; Park Nicollet Clinic; Peytan Manning Children’s Hospital (PMCH) Ear, Nose and Throat Center; Boys Town Ear, Nose & Throat Institute; ENT & Allergy Associates, LLP; Frisco Family (formerly McKinney ENT); Advanced ENT & Allergy (formerly Commonwealth ENT); Medical University of South Carolina; David John Bailey, MD, PA; John Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Otolaryngology–HNS, Division of Pediatric Otolaryngology; Medical College of Wisconsin, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin; University of Texas Medical Branch; Summit Medical Group; University of Kansas Pediatric Otolaryngology; University of Michigan; Mayo Clinic; Caryn Garriga MD LLC (formerly Chesterfield Pediatrics); Tots Thru Teens Pediatric; Pediatric Healthcare Unlimited; and Fenton Pediatrics. We would also like to thank the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head Neck and Surgery Foundation (AAOHNSF) and its BEST ENT Network and Outcomes, Research and Evidence-Based Medicine (OREBM) Committee for its oversight and assistance in early study organization. We would especially like to thank Stephanie Jones for her project management of the study and Sarah O’Connor for coordination and data entry. Last, we would like to acknowledge Sam Walters for his assistance in data clean-up.

Funding source: This study was funded solely by the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation: Provided access to the BEST-ENT and the CHEER research network for recruitment of patients; provided reimbursement to participants for their time; collated and entered data into a Microsoft Access database.

Footnotes

This article was presented at the 2013 AAO-HNSF Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO; September 29–October 3, 2013; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Author Contributions

Sarah J. Blank, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; David J. Grindler, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; Kristine A. Schulz, conception and design of the study, acquisition and interpretation of the data, revision of the article, final approval of the manuscript; David L. Witsell, conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, revision of the article, final approval of the manuscript; Judith E. C. Lieu, conception and design of the study, acquisition/analysis/interpretation of the data, revision of the article, final approval of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

Sponsorships: None.

References

- 1.Boruk M, Lee P, Faynzilbert Y, Rosenfeld RM. Caregiver well-being and child quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chenevier DG, LeLorier J. A willingness-to-pay assessment of parents’ preference for shorter duration of treatment of acute OM in children. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:1243–1255. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523120-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberger D, Bilenko N, Liss Z, Shagan T, Zamir O, Dagan R. The burden of acute OM on the patient and the family. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:576–558. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, Balzano A. Quality of life for children with OM. Arch Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049–1054. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900100019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Neighbors K, et al. The PedsQL Infant Scales: feasibility, internal consistency, reliability, and validity in healthy and ill infants. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. PROMIS® Parent Proxy Report Scales: an item response theory analysis of the parent proxy report item banks. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1223–1240. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0025-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouwer CNM, Rovers MM, Maillé AR, et al. The impact of recurrent acute OM on the quality of life in children and their caregivers. Clin Otolaryngol. 2005;30:258–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2005.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tube placement in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(1) suppl:S1–S35. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Witsell DL, Dolor RJ, Stinnett S, Hannley M. Quality of life of patients with otitis media and caregivers: a multicenter study. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1798–1804. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000231305.43180.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witsell DL, Stewart MG, Monsell EM, et al. The cooperative outcomes groups for ENT: a multicenter prospective cohort study on the outcomes of tympanostomy tubes for children with otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;130:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laine MK, Tähtinen PA, Ruuskanen O, et al. Symptoms or symptom-based scores cannot predict acute otitis media at otitis-prone age. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1154–e1161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grindler DJ, Blank SJ, Schulz KA, Witsell DL, Lieu JEC. Impact of otitis media on severity of children’s quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1177/0194599814525576. [published online March 13, 2014] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman R, Owens T, Simel DL. Does this child have acute otitis media? JAMA. 2003;290:1633–1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]