Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine patterns of pharmacotherapy for beneficiaries in a high risk Medicare Advantage population diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of 2,338 Medicare Advantage beneficiaries diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Pharmacotherapy treatment was assessed via receipt of 1) a mood stabilizer and/or antipsychotic (i.e. guideline concordant bipolar care) and 2) unopposed antidepressant (AD) (i.e., without prescription of a mood stabilizer or an antipsychotic). Logistic regression was used to examine correlates of bipolar disorder care.

Results

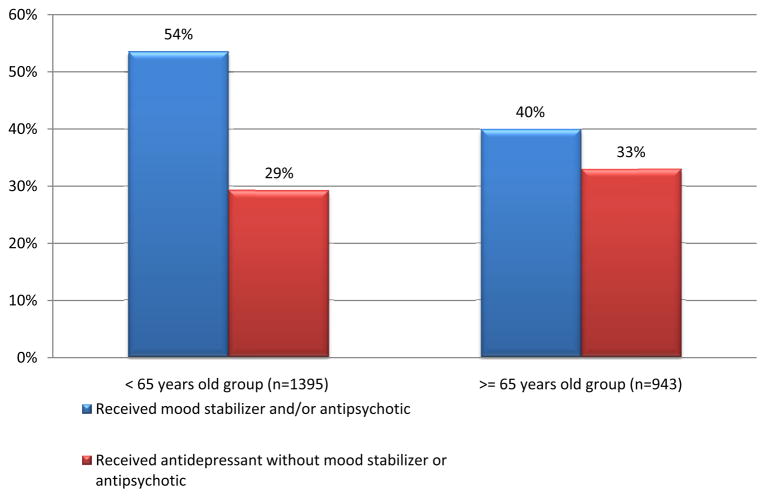

Among those less than 65 years old (n=1395), 54% received guideline concordant therapy, and 29% received unopposed AD therapy. Among those 65 years old and older (n=943), 40% received guideline concordant therapy, and 33% received unopposed AD therapy.

Conclusion

Overall, about one-half of beneficiaries in this Medicare Advantage plan received guideline concordant pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder, while approximately one-third received an unopposed antidepressant prescription. Antipsychotic medications accounted for the majority of mono-therapy observed. This study identified opportunities for further improvements in the pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder in high risk Medicare patients.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder, Mental Health, Mood Disorders, Old age, Medicare, Quality of Care

Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental illness that frequently co-occurs with other medical illnesses, including cardiovascular conditions, and is associated with significant morbidity/mortality (1). Recent studies suggest that those with this affective illness die approximately 10 years earlier than the general population, primarily from medical disorders (2). This disorder, especially during depressive episodes, has also been found to be associated with decreased productivity and increased days missed at work (3). Nationally representative estimates of community dwelling older individuals have reported a 12-month prevalence of 0.9% (4). In an epidemiologic study of a nationally representative sample of Americans, only about half (49%) of patients with bipolar disorder have received any treatment (either in the mental health or general medical system) in the past 12 months (5), while in another study of bipolar patients served in a Health Maintenance Organization (6), up to 83% had at least one bipolar medication filled in a one year study period. However, little data is available describing the quality of bipolar care in Medicare beneficiaries.

Medicare Advantage plans (developed by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003) are private health plans paid by Medicare to provide benefits to their beneficiaries (7). As of 2012, 13.1 million Medicare beneficiaries have chosen to enroll in these private plans. The purpose of this descriptive study is to examine the patterns of pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder for a large sample of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries and to identify opportunities for improvements in care for this high risk population.

Methods

Study setting and participants

The study sample includes Humana beneficiaries enrolled from November 2008 to January 2010 (n=2338) who had a claims diagnosis of bipolar disorder (International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) codes: 296.0, 296.1, 296.4-8). Those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (295.0-9) were excluded from this study as treatment with an antipsychotic medication is a first line treatment, which would contribute to an overestimate of guideline concordant bipolar care. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Washington, Seattle and by Humana’s privacy and legal departments.

Measurements

Based on evidence based treatment guidelines, two indicators of bipolar disorder pharmacotherapy were created: 1) Receipt of mood stabilizer and/or antipsychotic (i.e. guideline concordant bipolar care) and 2) Receipt of an antidepressant without a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic (i.e., unopposed antidepressant treatment) (8, 9). The mood stabilizer group included carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, and lithium. Although treatment guidelines recommend second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) only, we also included first generation antipsychotics (FGAs) in order to reflect real world prescribing practices. The FGAs included chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, pimozide, perphenazine, thioridazine, thiothixene, loxapine, and trifluoperazine, while the SGAs included aripiprazole, clozapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone, molindone, risperidone, quetiapine, and olanzapine. The following antidepressants were included in this study: amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, doxepin, clomipramine, desipramine, amoxapine, maprotiline, nefazodone, trazodone, bupropion, mirtazapine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, citalopram, escitalopram, duloxetine, and venlafaxine.

Member level factors include age, gender, hierarchical condition category (HCC) score (10), insurance type, and region of country. The HCC was introduced by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services as a risk adjustment method to adjust capitation payments to private Medicare plans. The HCC model takes into account demographic and diagnostic codes (based on ICD-9) to generate a summary risk score for patients (10, 11). HCC was used to adjust for medical complexity of patients in our analysis. Psychiatric comorbidities were based on ICD-9 diagnostic codes in claims diagnoses and included the following: depressive disorders (296.2, 296.3, 296.90, 300.4, 309.28, 311) and dementia (290).

Statistical analyses

This study is a descriptive secondary analysis of prospectively collected administrative data. As this is an exploratory study, an a priori hypothesis was not formulated. Data were analyzed using STATA version 11. The sample consisted of 2338 members who had a bipolar disorder diagnosis in one or more insurance claims during the study period. Beneficiaries who qualify for Medicare before age 65 represent a distinctly different population than those who are eligible to enroll in Medicare upon reaching age 65 (e.g. younger Medicare beneficiaries are typically also eligible for Medicaid and thus are considered “dually eligible”). Therefore, two main age groups were created: those less than 65 years old and those 65 years old and older.

To describe the correlates of receipt of bipolar disorder treatment, logistic regression models were constructed with the following independent variables for each age cohort independently: gender, hierarchical conditional categories, dual eligibility, depression, dementia, and region (South, Northeast, Midwest, and West, as defined by Humana Cares markets. The dependent variables were: 1) Receipt of guideline concordant bipolar care and 2) Receipt of unopposed antidepressant treatment.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with bipolar disorder stratified by age. The mean age was 52.7 (±8.1) and 73.9 (±7.0)for those under and over 65 years, respectively. The majority of participants in both groups were female (70% for the younger group and 66% for the older group). Overall, just under half (48.1%) of patients received guideline concordant pharmacotherapy, with 9.0% and 29.6% of patients prescribed mood stabilizer mono-therapy or antipsychotic mono-therapy, respectively. Thirty-one percent of the sample received unopposed antidepressant treatment. Rates of receipt of guideline concordant care or unopposed antidepressant treatment, stratified by age, are shown in Figure 1. In the younger age group, dually eligible individuals were more likely to receive guideline concordant treatment (OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.45–2.23) and were less likely to receive unopposed antidepressant care (OR=0.77, 95% CI: 0.77–0.98) (Table 2). Individuals with bipolar disorder who received unopposed antidepressant care had greater medical severity (OR=1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.24) and rates of depression diagnoses (OR=2.22, 95% CI: 1.58–3.11), while also having lower rates of dementia (OR=0.70, 95% CI: 0.52–0.94) than those who did not receive this type of treatment (Table 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample with bipolar disorder diagnosis (%(n) or mean±SD) stratified by age groups

| < 65 y.o. (n=1,395) | ≥ 65 y.o. (n=943) | |

|---|---|---|

| age (sd) | 52.7±8.1 | 73.9±7.0 |

| gender (F) % | 69.8 (974) | 65.5 (618) |

| Hierarchical conditional categories (sd) | 1.9±1.5 | 2.1±1.4 |

| Dual eligible % | 48.5 (677) | 24.6 (232) |

| Region % | ||

| Northeast | 2.9 (41) | 3.3 (31) |

| Midwest | 18.9 (263) | 24.2 (228) |

| South | 69.3 (967) | 61.7 (582) |

| West | 8.9 (124) | 10.8 (102) |

| Depression % | 75.3 (1051) | 71.7 (676) |

| Dementia % | 12.2 (170) | 36.0 (339) |

Figure 1.

Bipolar disorder care stratified by age groups (%)

Table 2.

Logistic regression models for the correlates of receiving bipolar disorder care for patients < 65 years old (Odds ratio=OR)a

| Received any bipolar disorder care (mood stabilizer or antipsychotic) | Received unopposed antidepressant care | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| gender (F) | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 1.30 (0.99–1.69) |

| Hierarchical conditional categories | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) |

| Dual eligible | 1.80 (1.45–2.23)c | 0.77 (0.61–0.98)b |

| Region (South is reference) | ||

| Northeast | 1.08 (0.57–2.03) | 1.10 (0.56–2.2) |

| Midwest | 1.23 (0.93–1.62) | 0.81 (0.59–1.10) |

| West | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | 1.10 (0.73–1.65) |

| Depression | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 1.33 (0.99–1.77) |

| Dementia | 1.05 (0.76–1.46) | 1.04 (0.73–1.47) |

Adjusted for time enrolled in program,

p<0.05,

p<0.005

Table 3.

Logistic regression models for the correlates of receiving bipolar disorder care for patients ≥ 65 years old (Odds ratio=OR)a

| Received any bipolar disorder care (mood stabilizer or antipsychotic) | Received unopposed antidepressant care | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| gender (F) | 1.07 (0.81–1.42) | 1.35 (0.99–1.83) |

| Hierarchical conditional categories | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 1.13 (1.02–1.24)b |

| Dual eligible | 1.15 (0.85–1.57) | 0.93 (0.67–1.28) |

| Region (South is reference) | ||

| Northeast | 1.11 (0.53–2.33) | 0.72 (0.32–1.62) |

| Midwest | 0.99 (0.72–1.36) | 0.71 (0.51–1.00) |

| West | 1.29 (0.84–1.97) | 0.82 (0.51–1.31) |

| Depression | 1.31 (0.97–1.77) | 2.22 (1.58–3.11)c |

| Dementia | 1.31 (0.99–1.72) | 0.70 (0.52–0.94)b |

Adjusted for time enrolled in program,

p<0.05,

p<0.005

Discussion

Our study showed that among these chronically ill Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, slightly less than half (48%) received guideline concordant pharmacologic treatments, while about one-third (31%) receive unopposed antidepressant treatment. When examining mono-therapy care, antipsychotics accounted for a greater portion of guideline concordant care than mood stabilizers (30% compared with 9%). This figure reflects the trend of increased use of antipsychotic medications for multiple mental health disorders (12). Similar to our previous study of Humana beneficiaries with depression, we found some regional variations in care, although there was less regional variation in care for bipolar disorder compared with depressed patients. We found substantially lower rates of guideline concordant pharmacologic treatment of those with bipolar disorder compared in this earlier study of patients with depression served in the same program (13).

In the younger age group, those with dual eligibility were more likely to receive guideline concordant care, perhaps because dual eligibility serves as a proxy for psychiatric severity. This group was also less likely to receive unopposed antidepressant treatment possibly due to closer monitoring of mental health care for these individuals. In the older age group, those with higher medical complexity were more likely to receive unopposed antidepressant care. Those with depression diagnoses were more likely to receive unopposed antidepressant treatment, while those dementia diagnoses were less likely to receive such treatment. Depression diagnoses may reflect greater severity of depressive symptoms in those with bipolar disorder and the fact that bipolar patients most commonly present to health care providers with symptoms of depression rather than mania, accounting in part for the association with unopposed antidepressant prescriptions. However, the use of unopposed antidepressants in bipolar disorder is not recommended as it may increase the risk for the development of mixed or manic episodes and rapid cycling and decrease the likelihood of overall treatment response (14, 15).

In a prior study of the general population, only 49% of patients received any care for bipolar disorder. To address such issues, a number of care management programs have been developed and offered as part of Medicare Advantage services to coordinate the care of high risk and high cost Medicare beneficiaries with multiple medical and behavioral health conditions (16). Opportunities for improving the quality of bipolar disorder care for chronically ill Medicare beneficiaries could include additional primary care provider interventions, community based behavioral health services, and specialized programs such as telephonic and in home care management. Specific services could include: educating and supporting the beneficiary to follow their provider’s concordant treatment (i.e. receipt of a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication and not receiving unopposed antidepressants) or ongoing patient monitoring, and care managers could monitor patients’ health status including behavioral health symptoms and work to support any provider recommended changes in psychotropic medications when indicated (i.e. stepped model of care) (17)

Given that this Medicare Advantage program offered enhanced care through telephonic care coordination, it is interesting that the rate of guideline concordant pharmacologic treatment was less than 50%. This highlights the importance programmatic evaluation with implementation of alternate or supplemental care models. Thus, it is important to seek further study and new and responsive ways to deliver care management, looking for effective in person, community based as well as telephonic models of care.

Another interesting point is that one third of patients received unopposed antidepressant treatment and the remaining patients received no care. Clearly, neither of these practices is supported by evidence based treatment guidelines. It is possible that these patients had less severe illness or chose not to fill prescriptions for mood stabilizers or antipsychotics and therefore represent a population in need of outreach. Thus, programs to identify effective strategies to engage patients in treatment are needed.

The major strength of this study is the nationally representativeness of the sample. Our study also has several limitations. The study is limited by its observational nature as well as limitations inherent in using claims data to identify patients with bipolar disorder. Although we have information on mood stabilizer/antipsychotic/antidepressant prescription fills, we do not have information on patient adherence to these medications. We were also unable to measure beneficiary demographics (including race/ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and medical diagnoses), provider, and health services factors that may influence the receipt of bipolar disorder care. Finally, we did not have reliable information on other services received for bipolar disorder such as the nature and frequency of psychotherapy or other mental health treatments.

Conclusion

Approximately one-half of patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in this Medicare Advantage population received guideline concordant bipolar treatment, while approximately one-third received unopposed antidepressant treatment. This study highlights the need for innovative inter-disciplinary models of care and quality improvement projects aimed at improving bipolar disorder care.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support:

The research was supported by the following grant from the Health Services Division of NIMH: T32 MH20021-14 (Dr. Katon) U01 (NIMH): Medicare Health Support Grant (MH0751590) (Dr. Unützer)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification:

Drs. Huang, Gören, Chan, Russo, and Unützer have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr. Katon has received honorariums for lectures from Eli Lilly, Forest, and Pfizer.

Dr. Hogan is employed by Humana Cares, St. Petersburg, FL

Additional Contributions:

The authors also thank Nikesh Seth of Humana Cares for collection of the data used in the analyses.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fagiolini A, Forgione R, Maccari M, Cuomo A, Morana B, Dell’osso MC, et al. Prevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westman J, Hallgren J, Wahlbeck K, Erlinge D, Alfredsson L, Osby U. Cardiovascular mortality in bipolar disorder: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Unutzer J, Operskalski BH, Bauer MS. Severity of mood symptoms and work productivity in people treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(6):718–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High Occurrence of Mood and Anxiety Disorders Among Older Adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):489–96. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unutzer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, Bond K, Katon W. The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Special needs plans. Overview. [5/4/13]; Available from: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/specialneedsplans/

- 8.Duffy FF, Narrow W, West JC, Fochtmann LJ, Kahn DA, Suppes T, et al. Quality of care measures for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76(3):213–30. doi: 10.1007/s11126-005-2975-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children, and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. 2006 [cited 2013 May 4]; Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG38. [PubMed]

- 10.Pope G, Kautter J, Ellis R, Ash A, Ayanian J, Lezzoni L, et al. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financing Review. 2004;25(4):119–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P, Kim M, Doshi J. Comparison of the performance of the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) risk adjuster with the charlson and elixhauser comorbidity measures in predicting mortality. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10(1):245. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996–2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):195–205. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang H, Russo J, Bauer AM, Chan YF, Katon W, Hogan D, et al. Depression care and treatment in a chronically ill Medicare population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Risk of switch in mood polarity to hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar depression during acute and continuation trials of venlafaxine, sertraline, and bupropion as adjuncts to mood stabilizers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):232–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tondo L, Vazquez G, Baldessarini RJ. Mania associated with antidepressant treatment: comprehensive meta-analytic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(6):404–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCall N, Cromwell J. Results of the Medicare Health Support Disease-Management Pilot Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(18):1704–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1011785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Korff M, Tiemens B. Individualized stepped care of chronic illness. West J Med. 2000;172(2):133–7. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]