Abstract

Objectives

To investigate use of dual tests for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae on samples collected through the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) in England.

Design and setting

During May–July 2013, we delivered an online survey to commissioners of sexual health services in the 152 upper-tier English Local Authorities (LAs) who were responsible for commissioning chlamydia screening in people aged 15–24 years.

Main outcome measures

(1) The proportion of English LAs using dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP; (2) The estimated number of gonorrhoea tests and false positives from samples collected by the NCSP, calculated using national surveillance data on the number of chlamydia tests performed, assuming the gonorrhoea prevalence to range between 0.1% and 1%, and test sensitivity and specificity of 99.5%.

Results

64% (98/152) of LAs responded to this national survey; over half (53% (52/98)) reported currently using dual tests in community settings. There was no significant difference between LAs using and not using dual tests by chlamydia positivity, chlamydia diagnosis rate or population screening coverage. Although positive gonorrhoea results were confirmed with supplementary tests in 93% (38/41) of LAs, this occurred after patients were notified about the initial positive result in 63% (26/41). Approximately 450–4500 confirmed gonorrhoea diagnoses and 2300 false-positive screens might occur through use of dual tests on NCSP samples each year. Under reasonable assumptions, the positive predictive value of the screening test is 17–67%.

Conclusions

Over half of English LAs already commission dual tests for samples collected by the NCSP. Gonorrhoea screening has been introduced alongside chlamydia screening in many low prevalence settings without a national evidence review or change of policy. We question the public health benefit here, and suggest that robust testing algorithms and clinical management pathways, together with rigorous evaluation, be implemented wherever dual tests are deployed.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The English National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) aims to diagnose and control chlamydia in all sexually active people aged 15–24 years, but no such community-based screening programme exists for gonorrhoea.

We undertook a national survey of Local Authority (LA) commissioners of chlamydia screening to investigate use of dual tests, which simultaneously test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, in community-based settings (excluding specialist sexual health services).

Response to the LA survey was high and similar across the geographical regions in England. There was no evidence to suggest participation was associated with area-level Index of Multiple Deprivation or NCSP characteristics.

The study is limited by the self-reported nature of the survey responses, which might be subject to reporting bias. Our data might underestimate the proportion of LAs using dual tests because commissioners might not always be aware that dual tests are being used for NCSP samples. Most survey questions had item non-response of around 14%.

In over half of LAs in England, dual tests are already being used on samples collected by the NCSP, and in many areas gonorrhoea test results are returned to patients prior to the result being confirmed.

Introduction

The English National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) offers sexually active, asymptomatic, women and men, aged 15–24 years, opportunistic testing to diagnose and control Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia) infection in England.1 In 2012, over 1.2 million screening tests were performed for young people in community-based sexual health clinics in England (ie, outside of specialist sexual health clinics, called genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics in the UK), with over 80 000 chlamydia infections diagnosed.2 Screening is offered by a variety of providers, including contraception, sexual health and termination of pregnancy services, pharmacies and primary care. Since 2013, commissioning arrangements have been undertaken through Local Authorities (LAs), which are regional local government administrative bodies.3

The test of choice for chlamydia detection is the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), and a range of assays, with extremely high sensitivity and specificity, are available.4 Many NAATs allow dual detection of chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea) using a single specimen and the same assay,4 and it has become inexpensive and straightforward to simultaneously test for both infections.5 From a simplistic viewpoint, this technological development may appear advantageous to public health.5–7 However, new guidance for England on testing for gonorrhoea found only sparse evidence for selective community screening, and no evidence to support widespread unselected screening in community-based settings.8 9 Although chlamydia and gonorrhoea cause similar disease and symptoms, there are important differences in the population distribution and the microbiology of testing for these infections that need consideration.10 Unlike chlamydia, the prevalence of gonorrhoea is very low in the general population (<0.1% and therefore approximately 10-fold lower),11 and concentrated in specific groups (including those attending specialist GUM clinics).12

Where prevalence is low, the positive predictive value (PPV) of a single test will also be low, but the problem of low PPV can be resolved by undertaking a supplementary test on samples that initially screen positive. Although the prevalence of gonorrhoea in patients attending community-based services, such as NSCP settings, might be higher than in the general population (ranging from 0.3% to 1.7% outside London,6 13–15 and up to 4.1% in South London),16 lack of proper confirmatory strategies means that the available studies might overestimate prevalence.9 Together, the low prevalence of gonorrhoea and the potential for cross-reaction with non-gonococcal Neisseria spp. mean that high rates of false-positive results might occur if gonorrhoea screening is undertaken on NCSP samples.10

In 2007, a laboratory survey found that 29% of hospital-based microbiology laboratories in England and Wales were already using dual tests to diagnose chlamydia and gonorrhoea.17 A recent repeat of this survey suggests that this proportion has increased to 85% (Toby et al, Public Health England (PHE), unpublished study). However, it is not known whether this has led to widespread gonorrhoea screening being undertaken on samples collected by the NCSP. In this study, we (1) undertook a survey of LA commissioners to understand the extent to which dual tests are being deployed for samples collected by the NCSP, (2) collected data about the clinical care pathways used when gonorrhoea is detected and (3) linked the survey data with national surveillance data to estimate the likely number of gonorrhoea diagnoses and false-positive gonorrhoea results occurring in England through the use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP.

Methods

Survey methodology

During May–July 2013, we delivered an online questionnaire (using the PHE web-based survey tool, ‘Select Survey’) to commissioners of sexual health services who were responsible for commissioning chlamydia testing in people aged 15–24 years for each of the 152 upper tier LAs in England (upper tier LAs are administrative bodies with a wide range of local government responsibilities, including public health). Such web-based surveys are easy to use and maximise response rates.18 The questionnaire used closed questions and dropdown menus to ask about: use of dual tests outside of GUM settings (ie, community-based sexual health screening), service setting and sample types, use of confirmatory testing where the screening test was reactive for gonorrhoea, patient information, and consent processes. Since not all commissioners were likely to understand technical molecular definitions used in relation to confirmatory testing, the questionnaire used the following pragmatic definition for a confirmatory test: “a second test used to confirm the diagnosis of gonorrhoea where the initial screening test is positive for gonorrhoea.” The questionnaire was piloted to test usability, understanding, clarity and question flow; it included 29 questions and took approximately 20 min to complete. Respondents were recruited by email using a national list of LA sexual health commissioners, which covered the whole of England, and the survey was advertised in the quarterly NCSP newsletter.

Statistical analysis

Survey data were extracted to Microsoft Excel and a descriptive analysis was undertaken. The denominator for descriptive analyses was the number of LAs, which varied by item non-response. Using Stata (V.12.1), independent samples t test compared area-level characteristics between LA responders and non-responders and between LAs using and not using dual tests. Chlamydia diagnosis rates (per 100 000 population) and chlamydia testing coverage included diagnoses and testing in community-based and GUM settings collected through the Chlamydia Testing Activity Dataset (CTAD) and the GUM Clinic Activity Dataset (GUMCAD), and gonorrhoea diagnosis rates (per 100 000 population) included diagnoses made in GUM clinics collected through GUMCAD.2 19

Estimating the number of gonorrhoea false positives and confirmed positives

For each LA using dual tests, PHE CTAD2 data on the number of chlamydia tests performed outside of GUM clinics in 2012 was used as a proxy for the total number of gonorrhoea tests performed through use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP (excluding screening in GUM). Using this figure, we estimated the absolute number of unconfirmed reactive tests and the number of confirmed diagnoses, using published specificity estimates for a commercial dual test assay.20 We did this for two scenarios for the overall prevalence of gonorrhoea in community-based settings, 0.1% and 1%, which represent plausible minimum and maximum values, respectively.9 11

Ethics

This work was undertaken with data collected and held within the requirements of the Data Protection Act and in accordance with data sharing best practice and PHE guidelines.21 The study did not use individual patient data and did not require or seek ethical approval.

Results

LA survey response and use of dual tests

Overall, 98/152 of LAs responded to the survey, which equates to a response rate across England of 64% (table 1). The proportion of LAs responding was at least 50% in all 15 PHE centre areas, and the area-level characteristics of responding and non-responding LAs were statistically similar. Comparison between responding and non-responding LAs included area-level Index of Multiple Deprivation22 (mean Index of Multiple Deprivation score 22.9 vs 23.1; p=0.89), mean chlamydia positivity among those testing and aged 15–24 years (7.9% vs 7.8%; p=0.63), mean chlamydia diagnosis rate (2152/100 000 vs 1870/100 000; p=0.06), mean chlamydia testing coverage among those aged 15–24 years (27% vs 24%; p=0.06) and mean GUM gonorrhoea diagnosis rate estimated from GUM diagnoses (43/100 000 vs 39/100 000; p=0.68) for each LA area.

Table 1.

LA survey response and reported use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP for people aged 15–24 years, with estimated numbers of gonorrhoea (NG) tests performed, confirmed diagnoses, and unconfirmed reactive tests for 2012

| PHE region | Number of LAs | Survey response, number of LAs (%) | LAs (%) using dual tests* | Non-GUM CT tests† | If community-based NG prevalence is 0.1% | If community-based NG prevalence is 1.0% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated NG diagnoses‡ | Estimated unconfirmed reactive NG tests (PPV=17%)§ | Estimated NG diagnoses‡ | Estimated unconfirmed reactive NG tests (PPV=67%)§ | |||||

| All | 152 | 98 (64) | 52 (53) | 456 085 | 456 | 2278 | 4561 | 2258 |

| London | 33 | 21 (64) | 14 (67) | 98 250 | 98 | 491 | 983 | 486 |

| Midlands and East of England | 35 | 26 (74) | 6 (23) | 67 362 | 67 | 336 | 674 | 333 |

| North of England | 50 | 34 (68) | 21 (62) | 194 321 | 194 | 971 | 1943 | 962 |

| South of England | 34 | 17 (50) | 11 (65) | 96 152 | 96 | 480 | 962 | 476 |

*Number and percentage of LAs using dual tests out of those responding to the survey.

†Number of non-GUM CT tests performed in all LAs using dual tests as a proxy for the number of gonorrhoea screening tests performed, using data extracted from CTAD which comprises all chlamydia testing carried out in England.

‡Estimated number of confirmed NG diagnoses arising from use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP (non-GUM) if NG prevalence is 0.1% or 1%.

§Estimated number of reactive but unconfirmed NG tests arising from use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP (non-GUM) if NG prevalence is 0.1% or 1% and the sensitivity and specificity of test are 99.5%.

CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; CTAD, Chlamydia Testing Activity Dataset; GUM, genitourinary medicine; LA, Local Authority; NCSP, National Chlamydia (CT) Screening Programme; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; PPV, positive predictive value.

Over half (53% (52/98)) of responding LAs reported commissioning use of dual tests for samples collected by the NCSP, 45% (44/98) had never commissioned dual tests, and 2% (2/98) had previously commissioned dual tests or did not know (table 1). Most LAs (82% (37/45)) reported using dual tests in at least five different non-GUM settings, including Contraception and Sexual Health and Sexual and Reproductive Health services (98% (44/45)) and primary care (91% (41/45)) settings, as well as in termination of pregnancy services (87% (39/45)) and through remote sample collection by post or internet (80% (36/45)).

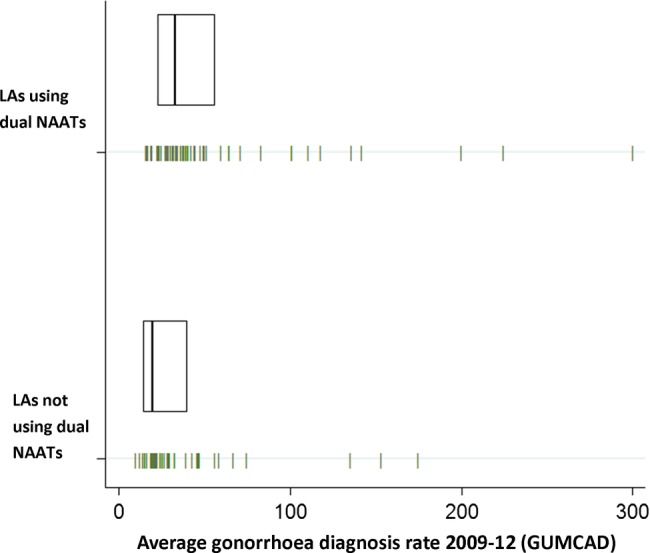

At an area level, there was no significant difference in Index of Multiple Deprivation, chlamydia positivity among those testing and aged 15–24 years, chlamydia diagnosis rate, or mean chlamydia testing coverage among those aged 15–24 years, when comparing LAs using and not using dual tests (table 2). Mean gonorrhoea diagnosis rates based on diagnoses made in GUM clinics were higher (53 vs 32/100 000; p=0.03) in LAs using dual tests compared with those not using. Nevertheless, most LAs had low gonorrhoea diagnosis rates that were below 50/100 000 (figure 1). We noted three LAs where dual tests were not being used, all in London, where GUM gonorrhoea diagnosis rates were above 100/100 000, placing these areas inside the top 10% nationally.

Table 2.

Comparison of area-level characteristics between LAs reporting current commissioning of dual tests and those not*

| Number of LAs | Mean chlamydia diagnosis rate/100 000† | Mean chlamydia testing coverage‡ | Mean gonorrhoea diagnosis rate/100 000§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using dual tests | 52 | 2254.8 | 28.6% | 52.7 |

| Not using dual tests | 46 | 2063.2 | 26.2% | 32.4 |

| p Value difference | – | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.03 |

*No significant difference was found by NCSP chlamydia positivity rate (p=0.93), LA Index of Multiple Deprivation (p=0.88), or the proportion of NCSP services provided by GUM or GP, but the proportion of services provided by CSHS was higher in those LAs using dual tests (19.4% vs 8.6%; (p<0.01)).

†Chlamydia diagnosis rates (per 100 000 population) include diagnoses made in community-based and GUM settings collected through CTAD and GUMCAD.

‡Chlamydia testing coverage includes tests performedin community-based and GUM settings collected through CTAD and GUMCAD.

§Gonorrhoea diagnoses (per 100 000 population) include diagnoses made in GUM clinics collected through GUMCAD.

CSHS, community sexual health services; CTAD, Chlamydia Testing Activity Dataset; GP, general practice; GUM, genitourinary medicine; GUMCAD, GUM Clinic Activity Dataset; LA, Local Authority; NCSP, National Chlamydia (Chlamydia trachomatis) Screening Programme; PPV, positive predictive value.

Figure 1.

Mean gonorrhoea (NG) diagnoses per 100 000 population (made in GUM clinics) between 2009–2012 by whether LAs use dual tests on samples collected by the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (1) Each vertical dash represents an LA, giving the four year average (2009–2012) for gonorrhoea diagnoses (per 100 000 population) for the 98 LAs responding to the survey, including diagnoses made in GUM clinics collected through GUMCAD (2) Boxes shows the median and lower and upper quartiles for four year average gonorrhoea diagnoses in each group. NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; GUM, genitourinary medicine; GUMCAD, GUM Clinic Activity Dataset; LA, Local Authority; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

Clinical care pathway for gonorrhoea

NCSP standards stipulate that patients should be given specific information about any testing that is additional to chlamydia and that informed consent for such testing is obtained.23 The standards also recommend that laboratories should not test for any infection unless this has been specifically requested, and that patients diagnosed with gonorrhoea in community-based settings should usually be referred to a GUM clinic.23

Overall, 36% (15/42) of LAs using dual tests reported providing gonorrhoea-specific patient information materials to patients, 45% (19/42) provided no gonorrhoea-specific information materials and 19% (8/42) did not know. Of those without gonorrhoea-specific patient information materials, 84% (16/19) reported that gonorrhoea was discussed within their NCSP patient information leaflet, while only 5% (1/19) of these LAs reported providing no gonorrhoea information (11% (2/19) did not know). Informed consent for testing of gonorrhoea was reported as assumed (on the basis that information was provided and the testing kit was returned) in 71% (25/35) of LAs, and taken in writing in 14% (5/35). Three per cent (1/35) of LAs did not obtain consent.

Although confirmatory testing (defined in the survey as a second test confirming the diagnosis of gonorrhoea) was reported as being used in 93% (38/41) of LAs, in practice, confirmation only occurred after referral to specialist sexual health services in most areas. In total, 63% (26/41) of LAs reported referring patients to sexual health services on the basis of a reactive screening test, 17% (7/41) referred after confirmatory testing, 15% (6/41) did not refer patients to another service and 10% (4/41) did not know.

Estimating the number of false-positive and confirmed positive gonorrhoea tests

We used the LA survey data, national surveillance data,2 and published data on gonorrhoea prevalence in community-based settings9 11 to estimate the number of confirmed gonorrhoea diagnoses and false positives that might occur each year through the use of dual tests on samples collected by the NCSP (table 1). Using CTAD surveillance data from only the 52 LAs that reported using dual tests, we estimated that at least 456 085 screening tests for gonorrhoea might be undertaken per year in non-GUM settings in England, which would lead to around 456 diagnoses of confirmed gonorrhoea per year if the overall prevalence is 0.1%. In this scenario, and assuming test sensitivity and specificity of 99.5% (which is likely to be at the upper end of existing platform specificity), approximately 2278 false-positive reactive screens would occur and the PPV of the screening test would be 17%. If the true prevalence of gonorrhoea was 1%, the number of false-positive tests occurring would be 2258, the number of confirmed diagnoses would be 4561 and the PPV would be 67%.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This is the first national study to investigate the use of dual tests for chlamydia and gonorrhoea on samples collected by the NCSP. Although the NCSP does not recommend simultaneous screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, our data suggest that over half of LAs in England already commission dual tests for NCSP samples. Thus, in many areas across England, screening for asymptomatic gonococcal infection has been introduced in low prevalence settings without a national evidence review or any change in national screening policy. Furthermore, we found evidence that reactive screening test results are being returned to patients prior to gonorrhoea infection being confirmed. Given that many reactive screening tests for gonorrhoea will be false positives due to low prevalence, this finding raises considerable concerns. We question the public health benefit of deploying dual tests for NCSP samples without careful consideration of the risks. Commissioners and providers may need to undertake appropriately powered pilot studies to decide whether dual tests are appropriate in their local areas. If dual tests are used, there are important implications for resource allocation in managing unconfirmed reactive tests and for the personal toll on an individual's well-being if the test is not confirmed; confirmatory tests should be performed before patients are informed about gonorrhoea diagnoses.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Response to the LA survey was high and similar across the geographical regions in England. There was no evidence to suggest participation bias associated with Index of Multiple Deprivation or NCSP area-level characteristics. It therefore seems likely that the responding LAs are representative of English LAs in their use of dual tests and that the data are generalisable. However, the study is limited by the self-reported nature of the survey responses, which might be subject to reporting bias. Furthermore, most survey questions had an item non-response of around 14%, which might reflect respondents’ lack of understanding, lack of knowledge about service specifications or reluctance to answer questions that might reveal suboptimal practice. Our data might underestimate the proportion of LAs using dual tests because commissioners might not always be aware that dual tests are being used for NCSP samples.

Although LAs using dual tests were more likely to be areas with higher rates of gonorrhoea diagnosis made in GUM clinics, which might indicate evidence-based policy making, this finding might also be explained by increased diagnosis of gonorrhoea in these areas arising from the introduction of dual tests.

Meaning of the study: possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policymakers

This study has significant implications for commissioners of sexual health services in LAs and for clinical services providing chlamydia screening. While screening for gonorrhoea in community-based settings might be appropriate in some areas where the prevalence is high, we show that dual tests are being used in areas where the prevalence and PPV are likely to be extremely low. Conversely, we also show that dual tests are not being used in some high prevalence areas that might benefit from targeted gonorrhoea screening.

The increased availability, technical ease, and declining cost of dual and, in due course, multiplex molecular testing platforms for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) make them attractive tools for laboratories that process high specimen volumes. The emergence of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) gonorrhoea is a major threat to global health and these molecular tests offer considerable public health benefits by facilitating detection and control of gonorrhoea.24 However, for commissioners, policymakers and providers, our study draws attention to the risk of false-positive test results and the need to minimise potential distress caused to patients. The harms of misdiagnoses include the direct emotional harm to individual patients arising from incorrect and stigmatising diagnoses and unnecessary partner notification,24 25 as well as the possibility of physical harm in the rare event that the unnecessary treatment causes side effects. Indirect harm may occur at a population level due to avoidable antibiotic usage (with implications for AMR) and clinical expense. Before any STI screening is introduced, the evidence on potential harms as well as benefits should be rigorously assessed and, wherever screening is introduced, robust testing algorithms and clinical management pathways implemented. A PHE toolkit is available to support LA sexual health commissioners in estimating PPVs for gonorrhoea testing in different population groups.26 Essential pathways include those for obtaining informed consent for testing of gonorrhoea and for performing confirmatory testing (using a supplementary NAAT with a different nucleic acid target) before returning results to patients or initiating management. These steps are likely to improve patient autonomy and safety, and avoid misdiagnosis, unnecessary clinical management and their associated costs.

Unanswered questions and future research

This paper highlights a broader issue that decisions about screening may be driven by the availability of diagnostic testing platforms rather than the evidence base.24 27 A WHO synthesis of emerging screening criteria, based on the Wilson and Yungner criteria, highlights the importance of identifying and responding to a recognised heath need, defining a target population, scientific evidence of screening effectiveness, and ensuring the overall benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms.28 Molecular-based testing brings considerable public health opportunities through rapid and highly sensitive detection of one or more pathogens simultaneously, often using non-invasive samples, with benefits to individual patients diagnosed with treatable infections, as well as enhancing surveillance and prevention efforts.27 29 For example, a multiplex point of care assay has already been developed to detect nucleic acid targets for 10 different pathogens.30 The US Food and Drug Administration cleared multiplex panels for respiratory infections in 2011, indicating a new era for the diagnosis of respiratory infection.31 However, there is an onus on healthcare commissioners and providers to understand the tests being ordered for individual patients and consider the implications for their deployment at a population level. The risk is that the availability and low costs of testing technologies may drive local policies and lead to inconsistent screening practices that lack an evidence base.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janette Clarke and Jane Hocking for their valuable comments as reviewers of the report. NF is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Lectureship.http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf

Footnotes

Contributors: NF contributed to the planning and design, wrote the first and revised subsequent drafts, designed and piloted the survey and undertook statistical analyses. IK designed and piloted the survey, contributed to statistical analyses, interpreted data and reviewed successive drafts. KF contributed to the planning and design, designed and piloted the survey, interpreted data and reviewed successive drafts. SD and KT did statistical analyses and reviewed successive drafts. CI contributed to the planning and design, interpreted data and reviewed successive drafts. GH led the study team, contributed to the planning and design, interpreted data and reviewed successive drafts. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.National chlamydia screening programme—NCSP home. http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ (accessed 25 Feb 2011).

- 2.HPA—CTAD: Chlamydia Testing Activity Dataset. http://www.hpa.org.uk/sexualhealth/ctad (accessed 30 May 2014).

- 3.Health and Social Care Act 2012, c.7. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted (accessed 30 May 2014).

- 4.British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Chlamydia trachomatis UK Testing Guidelines. 2010. http://www.bashh.org/documents/3352.pdf (accessed 21 Feb 2014).

- 5.Bignell CJ. Commentary. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:179–80. doi:10.1136/sti.2006.021816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavelle SJ, Jones KE, Mallinson H, et al. Finding, confirming, and managing gonorrhoea in a population screened for chlamydia using the Gen-Probe Aptima Combo2 assay. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:221–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavelle SJ, Mallinson H, Henning SJ, et al. Impact on gonorrhoea case reports through concomitant/dual testing in a chlamydia screening population in Liverpool. Sex Transm Infect 2007;83:593–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidance for the detection of gonorrhoea in England; including guidance on the use of dual testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Public Health England © Crown copyright (2014)

- 9.Fifer H, Ison CA. Nucleic acid amplification tests for the diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in low-prevalence settings: a review of the evidence. Sex Transm Infect 2014:pii: sextrans-2014-051588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ison C. GC NAATs: is the time right? Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1795–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Public Health England. Health Protection Report. 2013. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2013/hpr2313.pdf (accessed 6 Feb 2014).

- 13.Skidmore S, Copley S, Cordwell D, et al. Positive nucleic acid amplification tests for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in young people tested as part of the National Chlamydia Screening Programme. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:398–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler T, Edeghere O, Inglis N, et al. Estimating the positive predictive value of opportunistic population testing for gonorrhoea as part of the English Chlamydia Screening Programme. Int J STD AIDS 2013;24:185–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downing J, Cook PA, Madden HCE, et al. Management of cases testing positive for gonococcal infection in a community-based chlamydia screening programme. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:474–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao GG, Bacon L, Evans J, et al. Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in young subjects attending community clinics in South London. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:117–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benzie A, Alexander S, Gill N, et al. Gonococcal NAATs: what is the current state of play in England and Wales? Int J STD AIDS 2010;21:246–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayan Y, Paine CS, Johnson AJ. Responding to sensitive questions in surveys: A comparison of results from Online panels, face to face and self-completion interviews. 2009. http://www.ipsos-mori.com/Assets/Docs/Publications/Ops_RMC_Responding_Sensitive_Questions_08_03_10.pdf (accessed 21 Feb 2014).

- 19.Public Health England. Genitourinary Medicine Clinic Activity Dataset (GUMCADv2). http://www.hpa.org.uk/gumcad (accessed 30 May 2014).

- 20.Gen-Probe products. Aptima Combo 2 product information webpage. http://www.gen-probe.com/products-services/aptima-combo (accessed 30 May 2014).

- 21.Hughes G, Evans BG, Ncube F, et al. PHE HIV and STI Data Sharing Policy version 4. 2014. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1247816526850 (accessed 27 Jun 2014).

- 22.Payne RA, Abel GA. UK indices of multiple deprivation—a way to make comparisons across constituent countries easier. Health Stat Q 2012;53:22–3722410690 [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Chlamydia Screening Programme, Health Protection Agency. National Chlamydia Screening Programme Standards. 6th edn. 2012. http://www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk/ps/resources/core-requirements/NCSP%20Standards%206th%20Edition_October%202012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Low N, Unemo M, Skov Jensen J, et al. Molecular diagnostics for gonorrhoea: implications for antimicrobial resistance and the threat of untreatable gonorrhoea. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz AR, Effler PV, Ohye RG, et al. False-positive gonorrhea test results with a nucleic acid amplification test: the impact of low prevalence on positive predictive value. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:814–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidance for the detection of gonorrhoea in England—Publications—GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-for-the-detection-of-gonorrhoea-in-england (accessed 27 Aug 2014).

- 27.Klausner JD. The NAAT Is Out of the Bag. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:820–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andermann A, Blancquaert I, Beauchamp S, et al. Revisiting Wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: a review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/4/07–050112/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker JD, Bien CH, Peeling RW. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: recent advances and implications for disease control. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26:73–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriesel J, Bhatia A, Vaughn M, et al. P3-S5.05 Rapid point of care testing for ten sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87:A294–5 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russek-Cohen E, Feldblyum T, Whitaker KB, et al. FDA perspectives on diagnostic device clinical studies for respiratory infections. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:S305–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.