Abstract

Objective

To describe the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) burden of cervical dystonia (CD) and report on the HRQOL and patient perception of treatment benefits of abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport).

Design

The safety and efficacy of a single injection of abobotulinumtoxinA for CD treatment were evaluated in a previously reported international, multicenter, double-blind, randomised trial. HRQOL measures were assessed in the trial and have not been previously reported.

Setting

Movement disorder clinics in the USA and Russia.

Participants

Patients had to have a diagnosis of CD with symptoms for at least 18 months, as well as a total Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS) score of at least 30; a Severity domain score of at least 15; and a Disability domain score of at least 3. Key exclusion criteria included treatment with botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) or botulinum toxin type B (BoNT-B) within 16 weeks of enrolment.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to receive either 500 U abobotulinumtoxinA (n=55) or placebo (n=61).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Efficacy assessments included TWSTRS total (primary end point) and subscale scores at weeks 0, 4, 8, 12; a pain visual analogue scale at weeks 0 and 4; and HRQOL assessed by the SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36; secondary end point) at weeks 0 and 8.

Results

Patients with CD reported significantly greater impairment for all SF-36 domains relative to US norms. Patients treated with abobotulinumtoxinA reported significantly greater improvements in Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health and Role Emotional domains than placebo patients (p≤0.03 for all). The TWSTRS was significantly correlated with Physical Functioning, Role Physical and Bodily Pain scores, for those on active treatment.

Conclusions

CD has a marked impact on HRQOL. Treatment with a single abobotulinumtoxinA injection results in significant improvement in patients’ HRQOL.

Trial registration number

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, numbers NCT00257660 and NCT00288509.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The efficacy and safety of a single injection of abobotulinumtoxinA for cervical dystonia treatment were evaluated in an international, multicenter, randomised double-blind trial.

This paper presents previously unreported findings of health-related quality of life assessed during the international, multicenter, randomised double-blind trial of abobotulinumtoxinA.

The size of this study was small; therefore, studies with a larger sample size are required to demonstrate the outcomes of abobotulinumtoxinA treatment in a study population that is more representative of the general population.

Introduction

Dystonia, one of the most common movement disorders, with a spectrum of clinical features that range from severe generalised childhood dystonia, to adult-onset focal dystonias, to secondary dystonias and dystonias as a feature of complex neurological disorders.1 Dystonia can be focal (localised to a single body region) or can be spread to segmental (contiguous) or multifocal (non-contiguous) regions. Dystonia is characterised by motor manifestations, primarily sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements, postures or both.1 Cervical dystonia (CD), the most common form of focal dystonia, is characterised by sustained involuntary muscle contraction and/or twitching of cervical musculature resulting in abnormal postures and repetitive movements of the head.2 Depending on the muscles involved, the following head positions or combination of head positions, may occur: torticollis (rotation), laterocollis (tilting), anterocollis (flexion) and retrocollis (extension).3 CD may be accompanied by pulling or stiffness, pain and sensory symptoms in the affected area.4 The diagnosis of CD is based on clinical signs and symptoms: deviation in head/neck posture; involuntary neck movements resulting in turn, tilt and/or shoulder elevation; and neck pain.3 5

Besides the clinical problems of involuntary abnormal postures and repetitive movements frequently associated with pain, patients with CD present with a wide range of social disabilities and impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQOL).6 HRQOL is defined as the subjective perception of the impact of health status, including disease and treatment, on physical, psychological and social functioning and well-being.

Recognising the critical link between physical and psychological health allows a more holistic approach to patient care. By measuring HRQOL, we can ascertain the effects of a disease on individuals from the patient perspective and, thereafter, to some extent, be able to judge the benefit of therapeutic interventions. With CD, several physical and emotional factors such as reduced mobility, pain, low self-esteem, embarrassment, depression, anxiety and limited social interaction may be present. Pain is a predominant feature of CD and is reported in up to 75% of patients7 and is associated with reduced HRQOL. A study conducted by Degirmenci et al8 evaluated anxiety and depression in dystonia patients using the Hospital Anxiety Depression (HAD) scale and assessed quality of life using the SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36), a general measure widely used to assess HRQOL. Mean Anxiety and Depression subscale scores were higher in patients with dystonia when compared with the control group. Moreover, patients with dystonia had worse (lower) SF-36 scores for all domains when compared with controls.

AbobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport) 500 U was compared with placebo in two multicenter, double-blinded, randomised trials: one international9 and one in the USA.10 The international study included the SF-36 to evaluate treatment benefit with 500 U abobotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo as a secondary end point. As a result of the tremendous amount of research conducted using the SF-36 over the past two decades, population norms are available that can facilitate the interpretation of research results across a wide variety of patient populations, putting specific study data into ‘larger context.’11 In order to understand the HRQOL impairment unique to CD, SF-36 scores for the study sample were compared with other published scores for populations with various neurological conditions, in particular Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis; like CD, these conditions are generally progressive and affect motor and non-motor function. Specifically, because the HRQOL impairment of Parkinson's disease and that of multiple sclerosis have been well established,12 these conditions were deemed appropriate comparisons in evaluating the unique nature of HRQOL impairment due to CD.

Botulinum toxin (BoNT), a treatment with established safety and efficacy, has been recommended as first-line treatment for symptoms of CD.13 14 No botulinum toxin is indicated for improving HRQOL in CD. The reported benefits from BoNT are relief from pain, increased range of free movement and improved resting posture.15 16 BoNT injections typically offer temporary relief, and the symptoms gradually return. For CD, as for most other neurological disorders, more data exist regarding the efficacy of the Botulinum toxin type A (BoNT-A) compared with type B. BoNT-A and BoNT-B have been shown to reduce both symptom severity and pain.15 Currently, there are three major commercially available preparations of type A toxins: abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport (Ipsen Biopharm Ltd, Wrexham, UK)), onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox (Allergan, Inc; Irvine, California, USA)) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin (Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH; Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The potency units of abobotulinumtoxinA are specific to the preparation and assay method utilised. They are not interchangeable with other preparations of botulinum toxin products and, therefore, units of biological activity of one BoNT product cannot be compared to or converted into units of any other botulinum toxin products. Accordingly, information regarding the specific benefits of a particular BoNT-A preparation and the impact on HRQOL would be valuable.

The objectives of this article are to describe the HRQOL burden of CD, as measured at baseline in a previously reported randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pivotal clinical study,9 as well as report on the HRQOL and treatment benefits of abobotulinumtoxinA.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study design has been reported previously.9 An international, multicenter (movement disorder clinics in the USA (n=16) and Russia (n=4)), double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial was conducted between 10 October 2005 and 7 September 2006 to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a single injection of abobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of CD. To be eligible for study entry, patients had to have a diagnosis of CD with symptoms for at least 18 months, as well as the following baseline Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS) scores: a total score of at least 30; a Severity domain score of at least 15; and a Disability domain score of at least 3. The TWSTRS is an assessment of CD that includes a total CD rating score and three domain scores (Torticollis Severity, Disability and Pain).

Key exclusion criteria were standard for efficacy trials of BoNT and included treatment with BoNT-A or BoNT-B within 16 weeks of enrolment, any disease of the neuromuscular junction, previous phenol injection to the neck muscles, myotomy or denervation surgery in the neck/shoulder region, cervical contracture, suspected secondary non-responsiveness or a history of poor response to BoNT-A, pure anterocollis or retrocollis, symptom remission at screening, symptoms that could interfere with TWSTRS scoring or BoNT-A neutralising antibodies.

A total of 120 patients were to be recruited in the study to allow for 47 patients per treatment group to be evaluable on the primary efficacy end point (TWSTRS).9 Patients were randomised using a pregenerated randomisation code in a 1:1 ratio to receive an intramuscular injection of either 500 U abobotulinumtoxinA or placebo. Study medication was administered in a double-blind manner by intramuscular injection into two, three or four clinically indicated neck muscles during a single dosing session at baseline. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed by the ethics committee responsible for each site. All patients provided written, informed, institutional review board–approved consent before participation.

Assessments

Assessments have been described previously.9 The TWSTRS was determined at week 0 (baseline), at week 4 (primary), and at weeks 8 and 12 (post-treatment) by investigators trained in TWSTRS scoring. Pain was evaluated with the pain domain of the TWSTRS and a self-reported visual analogue scale (VAS) assessing pain in the past 24 h. Participants completed the pain VAS at baseline and week 4.

HRQOL was assessed using the SF-36, V.1.0. The SF-36 is a commonly used health profile that contains 36 items and includes multi-item domains to measure health status across eight dimensions: Physical Functioning, Role Limitations due to Physical Health Problems (Role Physical), Bodily Pain, Social Functioning, General Mental Health, Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems (Role Emotional), Vitality and General Health Perceptions. Responses to questions within each domain are summed and transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores suggesting better functioning. Participants completed the SF-36 at week 0 (baseline; prior to dosing) and at week 8 (post-treatment). SF-36 scores were generated according to published algorithms.11

Safety assessments included incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events, ECG, neurological and physical examinations and vital signs.

Statistical analyses

Burden of CD

Population norms are available for the SF-36 that can facilitate the interpretation of research results across a wide variety of patient populations.11 The unique burden of illness associated with CD was assessed by comparing patients’ baseline domain scores (regardless of enrolment location) to age-adjusted and gender-adjusted SF-36 domain scores for the US population norms.11 The 95% CI was computed for the baseline SF-36 scores relative to the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US population norms.

For comparisons relative to other neurological conditions, baseline SF-36 scores for the study sample were compared with other published scores for populations with Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. The patients with Parkinson's disease were patients attending six neurology centers in the USA, with a mix of Hoehn and Yahr scores representing early-stage, middle-stage and late-stage disease.17 The patients with multiple sclerosis were part of a longitudinal study in Ontario, Canada.18

Treatment effect analysis

Analyses were conducted on the full analysis set (ie, all randomised participants according to the treatment assigned at randomisation) for participants with a baseline and a week 8 SF-36 assessment.

Continuous primary (TWSTRS) and secondary variables (SF-36 domains) were analysed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for treatment group, baseline score (where appropriate), treatment history (ie, previous treatment with BoNT) and centre.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated among the eight week 8 SF-36 domain scores and the week 4 and week 8 TWSTRS domain scores and total score by treatment group.

A responder was defined, a priori, as a patient with a decrease in TWSTRS total score of at least 30% (at week 4) compared with baseline.9 Mean SF-36 scores by TWSTRS responder status were evaluated using a t test. Safety assessments were based on the safety population, which included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. Safety variables were summarised by descriptive statistics. Safety results have been reported previously.9

Results

Patient disposition and demographics

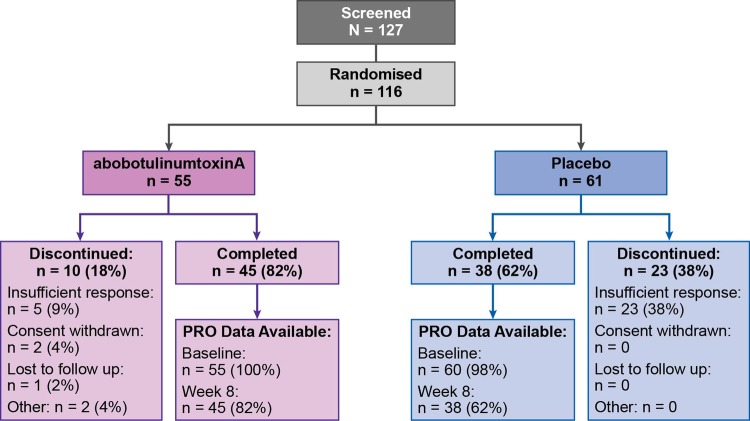

All 116 randomised patients (abobotulinumtoxinA n=55; placebo n=61) received at least one dose of study medication in the double-blind phase of the study and were included in the intent to treat and safety populations. Of these, 83 patients (abobotulinumtoxinA n=45; placebo n=38) were analysed in the HRQOL assessment. The mean (SD) age was similar across treatment groups: 51.9 (13.4) years for the abobotulinumtoxinA group and 53.9 (12.5) years for placebo group. Similarly, both treatment groups were predominantly female (67% in the abobotulinumtoxinA group and 62% in the placebo group). All other patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups (table 1).9 A total of 33 patients discontinued the study because of insufficient response, withdrawal of consent, loss to follow-up or other reasons (figure 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (intent-to-treat population)

| Characteristic | AbobotulinumtoxinA (n=55) | Placebo (n=61) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 51.9 (13.4) | 53.9 (12.5) |

| Median (range) | 53.0 (20–79) | 56.0 (28–78) |

| Sex, n (%) male | 18 (33) | 23 (38) |

| Race, n (%) Caucasian | 55 (100) | 61 (100) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (5) | 4 (7) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 52 (95) | 57 (93) |

| Height, cm | ||

| Mean (SD) | 167 (10.3) | 170 (8.5) |

| Median (range) | 167 (147–196) | 168 (154–193) |

| Weight, kg | ||

| Mean (SD) | 73.4 (13.8) | 77.4 (15.0) |

| Median (range) | 73.0 (46.4–108.0) | 75.5 (48.2–118.0) |

| Time since onset of cervical dystonia, years | 12.0 (8.8) | 11.8 (8.8) |

| Patients previously treated with botulinum toxin, n (%) | 45 (82) | 51 (84) |

| TWSTRS total score—mean (SD) | 43.8 (8.0) | 45.8 (8.8) |

| Participant's VAS for symptom severity, mm—mean | 67.7 (19.7) | 63.6 (18.9) |

| Investigator's VAS for symptom severity, mm—mean (SD) | 62.3 (15.8) | 65.3 (18.0) |

| SF-36 mental health summary score—mean (SD) | 44.5 (10.4) | 43.3 (11.1) |

| SF-36 physical health summary score—mean (SD) | 39.4 (8.8) | 43.2 (7.9) |

| Participant's VAS for pain severity, mm—mean (SD) | 47.4 (25.0) | 49.6 (24.5) |

| TWSTRS severity subscale score—mean (SD) | 20.4 (3.0) | 21.2 (2.8) |

| TWSTRS disability subscale score—mean (SD) | 12.9 (3.8) | 13.8 (4.5) |

| TWSTRS pain subscale score—mean (SD) | 10.6 (4.2) | 10.9 (4.6) |

SF-36, SF-36 Health Survey; TWSTRS, Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Comparison with US population and other neurological conditions

Baseline SF-36 scores for the patients with CD were lower (worse) than US population normative values11 for patients without CD in all domains. Before treatment with either abobotulinumtoxinA or placebo, patients with CD in this study reported significantly greater impairment for all eight domains of the SF-36 relative to the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US population normative values (table 2). For example, on study entry, patients with CD reported role physical impairments that were approximately 32% lower (worse) than the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US norm (domain score of 52.4 among patients with CD vs 76.6 for the US norm, p<0.05). Similarly, patients with CD reported experiencing significantly more pain than the age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US norm on study entry, with Bodily Pain scores that were 23% points lower (worse) for patients with CD than the US norms (47.7 vs 71.3, p<0.05).

Table 2.

Mean SF-36 scores for the normative US population and patients with cervical dystonia, Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis

| SF-36 domain | Cervical dystonia study sample (n=116) Mean (SD)* |

US normative sample† Mean |

Parkinson's disease‡ (n=150) Mean |

Multiple sclerosis§ (n=300) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Functioning | 67.2 (22.2) | 79.7 | 50.4 | 40.5 (30.2) |

| Role Physical | 52.4 (29.5) | 76.6 | 31.4 | 24.0 (36.8) |

| Bodily Pain | 47.7 (21.6) | 71.3 | 59.9 | 59.5 (27.2) |

| General Health | 61.4 (19.7) | 68.6 | 51.5 | 51.7 (24.1) |

| Vitality | 50.6 (18.1) | 60.1 | 46.1 | 35.1 (21.7) |

| Social Functioning | 64.8 (24.6) | 82.0 | 62.6 | 57.3 (27.6) |

| Role Emotional | 68.8 (27.1) | 80.6 | 49.0 | 56.1 (44.9) |

| Mental Health | 64.1 (18.4) | 74.8 | 67.1 | 67.1 (20.8) |

Like individuals with CD, patients with Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis report substantial impairments in HRQOL relative to US norms (table 2). However, each of these neurological conditions presents with a unique profile of HRQOL impairment. Patients with CD report the greatest limitation in the Bodily Pain domain, whereas patients with Parkinson's disease report the greatest impairments in the Role Physical domain and patients with multiple sclerosis report the greatest impairments in the Vitality domain. Each of these neurological conditions impairs patients physically, yet the presentation of the disease manifests itself differently in terms of HRQOL impairment.

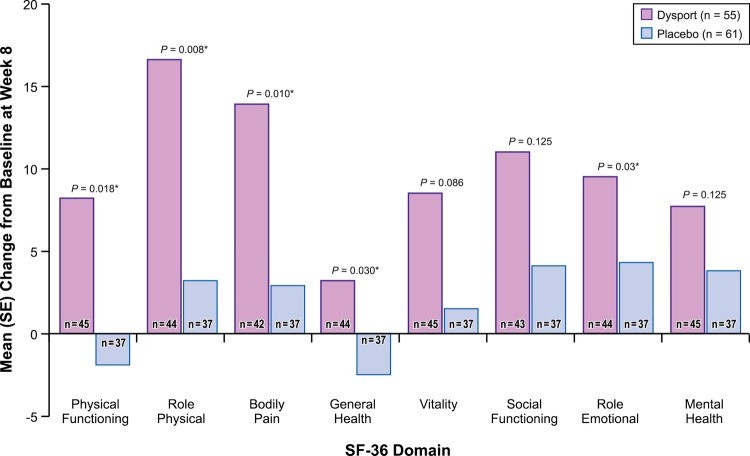

Treatment effect

Improvements from baseline to week 8 were observed for all eight SF-36 domains in the abobotulinumtoxinA group, whereas the placebo group showed some decline in Physical Functioning and little to no change in other SF-36 domains (table 3; figure 2). The largest improvements occurred in the Role Physical and Bodily Pain domains.

Table 3.

Mean (SE) SF-36 scores by treatment group: baseline and week 8

| SF-36 Domain | AbobotulinumtoxinA |

Placebo |

p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Baseline mean (SD) | Week 8 mean (SD) | Change mean (SD) | N | Baseline mean (SD) | Week 8 mean (SD) | Change mean (SD) | ||

| Physical Functioning* | 45 | 61.9 (20.0) | 70.1 (20.1) | 8.2 (16.0) | 37 | 68.2 (21.7) | 66.4 (23.4) | −1.9 (16.8) | 0.018 |

| Role Physical* | 44 | 46.3 (28.5) | 62.9 (25.1) | 16.6 (21.1) | 37 | 50.5 (29.9) | 53.7 (25.6) | 3.2 (24.0) | 0.008 |

| Bodily Pain* | 42 | 47.9 (23.0) | 61.8 (20.4) | 13.9 (19.7) | 37 | 49.0 (19.7) | 51.9 (22.0) | 2.9 (20.3) | 0.010 |

| General Health* | 44 | 58.9 (19.4) | 62.1 (18.4) | 3.2 (11.1) | 37 | 62.2 (19.6) | 59.7 (21.1) | −2.5 (10.6) | 0.030 |

| Vitality | 45 | 47.5 (15.6) | 56.0 (16.8) | 8.5 (15.0) | 37 | 50.5 (19.5) | 52.0 (19.2) | 1.5 (17.8) | 0.086 |

| Social Functioning | 43 | 62.2 (26.8) | 73.3 (22.9) | 11.0 (25.8) | 37 | 63.2 (25.0) | 67.2 (25.6) | 4.1 (15.6) | 0.125 |

| Role Emotional* | 44 | 71.0 (25.4) | 80.5 (21.5) | 9.5 (20.9) | 37 | 62.2 (28.0) | 66.4 (25.3) | 4.3 (26.8) | 0.030 |

| Mental Health | 45 | 62.6 (16.3) | 70.2 (15.8) | 7.7 (14.5) | 37 | 60.1 (20.9) | 63.9 (21.0) | 3.8 (15.2) | 0.125 |

Comparison between AbobotulinumtoxinA and placebo for change from baseline to week 8 using an ANCOVA model with baseline value as covariate.

*SF-36 domains that differed significantly (p<0.05) between abobotulinumtoxinA and placebo.

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; SF-36, SF-36 Health Survey.

Figure 2.

Mean (SE) change in SF-36 scores at week 8. *p<0.05. Positive changes in score indicate improvement.

Patients treated with abobotulinumtoxinA reported significantly greater improvements than placebo patients from baseline to week 8 in five of the eight SF-36 domains (table 3; figure 2). Specifically, patients treated with abobotulinumtoxinA reported significantly greater improvements in the Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health and Role Emotional domains (p≤0.03 for all) than patients treated with placebo.

Table 4 presents the correlations between the TWSTRS total and domain scores at week 4 with the week 8 SF-36 domain scores. As expected, the TWSTRS was significantly correlated with the Physical Functioning, Role Physical and Bodily Pain domain scores. The correlations between TWSTRS domain and total scores were consistently significantly correlated with the Role Physical and Bodily Pain domain scores for both treatment groups. The correlations ranged from −0.29 to −0.44 at week 4. Correlations were similar when evaluated with week 8 TWSTRS scores and week 8 SF-36 scores: −0.33 to −0.53 (week 8 correlations not shown).

Table 4.

Correlations between the week 8 SF-36 scores with the TWSTRS at week 4 by treatment group

| Week 4: correlation; p value; n |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total |

Disability |

Severity |

Pain |

|||||

| Abobotulinum-toxinA | Placebo | Abobotulinum-toxinA | Placebo | Abobotulinum-toxinA | Placebo | Abobotulinum-toxinA | Placebo | |

| Physical Functioning | −0.34; | −0.19; | −0.34; | −0.03; | −0.35; | −0.31; | −0.13; | −0.10; |

| 0.0278; | 0.2801; | 0.0257; | 0.8978; | 0.0223; | 0.0694; | 0.3969; | 0.55; | |

| 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | |

| Role Physical | −0.34; | −0.34; | −0.34; | −0.27; | −0.35; | −0.37; | −0.12; | −0.18; |

| 0.0295; | 0.0422; | 0.0270; | 0.1069; | 0.0229; | 0.0255; | 0.4265; | 0.2811; | |

| 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | |

| Bodily Pain | −0.41; | −0.35; | −0.31; | −0.29; | −0.20; | −0.44; | −0.53; | −0.14; |

| 0.00080; | 0.0345; | 0.0523; | 0.0871; | 0.2133; | 0.0076; | 0.0003; | 0.4296; | |

| 40 | 36 | 41 | 36 | 40 | 36 | 41 | 36 | |

| General health | −0.31; | 0.08 | −0.26 | 0.16 | −0.43 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.02 |

| 0.0422 | 0.6521 | 0.1459 | 0.3639 | 0.0045 | 0.7217 | 0.5785 | 0.9235 | |

| 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | |

| Vitality | −0.26 | −0.20 | −0.25 | −0.06 | −0.38 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.27 |

| 0.0983 | 0.2517 | 0.0963 | 0.7272 | 0.0123 | 0.4201 | 0.7860 | 0.1172 | |

| 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | |

| Social Functioning | −0.25 | −0.11 | −0.32 | 0.15 | −0.32 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.31 |

| 0.1217 | 0.5206 | 0.0394 | 0.3909 | 0.0437 | 0.6437 | 0.7280 | 0.0683 | |

| 41 | 36 | 42 | 36 | 41 | 36 | 42 | 36 | |

| Role Emotional | −0.18 | −0.14 | −0.29 | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.01 | −0.19 |

| 0.2877 | 0.4150 | 0.0612 | 0.9460 | 0.3874 | 0.3947 | 0.9383 | 0.2634 | |

| 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 42 | 36 | 43 | 36 | |

| Mental Health | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.22 | −0.38 | 0.16 | 0.14 | −0.24 |

| 0.2668 | 0.7815 | 0.3990 | 0.1949 | 0.0128 | 0.3365 | 0.3786 | 0.1502 | |

| 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | 43 | 36 | 44 | 36 | |

Correlations are negative as the TWSTRS and SF-36 are scored in opposite directions.

SF-36, SF-36 Health Survey; TWSTRS, Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale.

The proportion of participants classified as responders (achieving the predetermined 30% improvement in TWSTRS) was consistently higher for the abobotulinumtoxinA group than for the placebo group. For the abobotulinumtoxinA treatment group, 49% were classified as responders at week 4 and 58% were classified as responders at week 8. In contrast, for the placebo treated group, only 16% were classified as responders at week 4 and 26% at week 8.

Patients classified as TWSTRS responders (ie, those with a ≥30% improvement in TWSTRS at week 4) reported significantly greater improvements from baseline to week 8 in five of the eight SF-36 domains compared with patients who did not respond to treatment (table 5). Specifically, the largest improvements occurred in Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Bodily Pain, Vitality and Social Functioning (p≤0.03 for all).

Table 5.

Mean change in SF-36 scores by TWSTRS response status

| SF-36 domain | TWSTRS responder status Mean change in SF-36 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWSTRS non-responder (n=47) |

TWSTRS responder (n=36) |

Difference (responder–non-responder) | p Value | |

| Physical Functioning | −0.6 | 9.1 | 9.7 | 0.0091 |

| Role Physical | 3.5 | 19.3 | 15.8 | 0.0020 |

| Bodily Pain | 1.8 | 17.6 | 15.8 | 0.0005 |

| General Health | −1.5 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 0.0552 |

| Vitality | 0.8 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 0.0067 |

| Social Functioning | 2.8 | 14.3 | 11.5 | 0.0251 |

| Role Emotional | 2.8 | 12.5 | 9.7 | 0.0665 |

| Mental Health | 3.9 | 8.5 | 4.6 | 0.1691 |

SF-36, SF-36 Health Survey; TWSTRS, Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale.

SF-36, SF-36 Health Survey.

Discussion

Although CD is limited to involuntary muscle spasms of the neck, its detrimental effect on health status is comparable to progressive and generalised conditions clinically perceived to be of greater severity (such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease). Camfield19 conducted a survey of 150 patients with CD that included the SF-36 and the Beck anxiety and depression indexes. Patients with CD had lower scores in all eight SF-36 domains compared with controls in the UK, particularly in the Role Physical (41.6 vs 85.8), Bodily Pain (54.6 vs 81.5) and General Health (46.2 vs 73.5) domains. Domain scores were comparable to data from patients with mild-to-moderate multiple sclerosis and moderate epilepsy. Our results are similar to those of Camfield,19 in that baseline scores for patients with CD were lower (worse) than for US normative data, particularly for the Role Physical (52.4 vs 76.6) and Bodily Pain (47.7 vs 71.3) domains. Our findings support the implication that CD has a significant impact on health status that is comparable with other neurological disorders of high morbidity. CD appears to have a disproportionate negative impact on patients’ physical role limitation, despite their good physical functioning. One possible explanation is that pain limits such activities. Another possibility is that patients with CD consciously limit activities that make their dystonia visible to others to avoid mockery.20

A few studies have investigated the impact of CD on HRQOL and factors modifying a patient's ability to cope with this disease. Slawek et al21 conducted an HRQOL survey study in 101 patients previously treated with BoNT-A using the TWSTRS, a pain VAS (0–100%), the SF-36 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Patients’ baseline SF-36 scores were worse than those of healthy controls in all eight SF-36 domains. Improvements were observed 4 weeks after the single BoNT-A injections in all SF-36 domains, and in the VAS, TWSTRS and MADRS scores. The TWSTRS results did not correlate with any of the SF-36 domains. Longer treatment with BoNT-A was associated with better scores. Hefter et al22 23 conducted a prospective, open-label study of abobotulinumtoxinA in 516 de novo CD patients using the TWSTRS, the Craniocervical Dystonia Questionnaire (CDQ-24), patient diaries and a global assessment of pain. In contrast with the SF-36, which is a general measure of HRQOL, the CDQ-24 is a disease-specific questionnaire that evaluates HRQOL in patients with CD.24 The CDQ-24 has five subscales: Stigma, Emotional Well-being, Pain, Activities of Daily Living and Social/Family Life. At week 4, significant improvements were observed in CDQ-24 total and subscale scores that were sustained up to week 12. Significant reductions in patient diary item scores for activities of daily living, pain, and pain duration at week 4 and 12 were observed. Sixty-six per cent of patients reported pain relief (less or no pain) at week 4 and 74% at week 12. Improvements in quality of life and pain intensity for up to 12 weeks in patients with CD were observed after treatment with abobotulinumtoxinA.

Likewise, in our findings, patients treated with abobotulinumtoxinA reported significantly greater improvements in TWSTRS total mean scores at weeks 4, 8 and 12 (p≤0.019) compared with placebo.9 Improvements from baseline to week 8 were observed for all eight SF-36 domains in the abobotulinumtoxinA group, whereas the placebo group either stayed the same or became worse (with a decline in physical functioning). In this study, the SF-36 results did correlate with the TWSTRS for the Role Physical and Bodily Pain domains across treatment groups and time periods. AbobotulinumtoxinA was well tolerated in this study, as previously published.9

Our study is not without limitations that should be considered. First, the exclusion of those with suspected secondary non-responsiveness or a history of poor response to BoNT-A may have excluded those who might not experience a positive change in their HRQOL. Second, the size of this study was small. Studies with a larger sample size are required to demonstrate the outcomes of abobotulinumtoxinA treatment in a study population that is more representative of the general population. Lastly, there were quite a few withdrawals from the study, which could affect overall findings. There were a total of 33 patients (abobotulinumtoxinA n=10; placebo n=23) who discontinued the study, two-thirds of whom were in the placebo group.

Conclusion

CD has a marked impact on HRQOL for patients. Patients with CD report significantly worse functioning than that of their peers (age-adjusted and gender-adjusted US normative values). Results from this prospective, randomised controlled trial support the ability of abobotulinumtoxinA 500 U to provide efficacy in reducing motor symptoms in conjunction with significant improvements in HRQOL for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Jean Hubble, MD, formerly of Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc, for her clinical contributions to this paper; and Stephen Chang, PhD, formerly of Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc, for conduct of the statistical analyses of the trial data reported in this manuscript. Rosemarie Kelly, PhD, consultant to Ipsen, provided critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM, CM, CA and KC-M contributed substantially to the conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. MM and CM drafted the article. MM, CM, CA and KC-M revised it critically for important intellectual content. MM, CM, CA and KC-M approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc, Basking Ridge, NJ, USA.

Competing interests: CA is a former employee of Neurology Medical Affairs, Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals Inc, Basking Ridge, NJ, USA. MM, CM and KC-M, employees of RTI Health Solutions, were contracted by Ipsen Biopharmaceuticals, Inc to perform and report on the research described here.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Albanese A, Del Sorbo F, Comella C, et al. Dystonia rating scales: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord 2013;28:874–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Zandijcke M. Cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis). Some aspects of the natural history. Acta Neurol Belg 1995;95:210–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geyer HL, Bressman SB. The diagnosis of dystonia. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:780–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutvonen O, Dastidar P, Nurmikko T. Pain in spasmodic torticollis. Pain 1997;69:279–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan J, Brin MF, Fahn S. Idiopathic cervical dystonia: clinical characteristics. Mov Disord 1991;6:119–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pekmezovic T, Svetel M, Ivanovic N, et al. Quality of life in patients with focal dystonia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009;111:161–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Shlomo Y, Camfield L, Warner T. What are the determinants of quality of life in people with cervical dystonia? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:608–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degirmenci Y, Oyekcin DG, Bakar C, et al. Anxiety and depression in primary and secondary dystonia: a burden on health related quality of life. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res 2013;19:80–5 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truong D, Brodsky M, Lew M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A (Dysport) in cervical dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:316–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truong D, Duane DD, Jankovic J, et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum type A toxin (Dysport) in cervical dystonia: results of the first US randomized, double-blind, placeo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2005;20:783–91. 4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welsh M. Parkinson's disease and quality of life: issues and challenges beyond motor symptoms. Neurol Clin 2004;22:S141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson DM, Blitzer A, Brashear A, et al. Assessment: botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2008;70:1699–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallett M, Albanese A, Dressler D, et al. Evidence-based review and assessment of botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders. Toxicon 2013;67:94–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa J, Espirito-Santo C, Borges A, et al. Botulinum toxin type A therapy for cervical dystonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(1):CD003633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankovic J, Brin MF. Therapeutic uses of botulinum toxin. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damiano AM, McGrath MM, Willian MK, et al. Evaluation of a measurement strategy for Parkinson's disease: assessing patient health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 2000;9:87–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopman W, Coo H, Edgar C, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 2007;34:160–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camfield L. Quality of life in cervical dystonia. Mov Disord 2000;15(Suppl):143 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camfield L, Ben-Shlomo Y, Warner TT; Epidemiological Study of Dystonia in Europe Collaborative Group. Impact of cervical dystonia on quality of life. Mov Disord 2002;17:838–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slawek J, Friedman A, Potulska A, et al. Factors affecting the health-related quality of life of patients with cervical dystonia and the impact of botulinum toxin type A injections. Funct Neurol 2007;22:95–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefter H, Benecke R, Erbguth F, et al. An open-label cohort study of the improvement of quality of life and pain in de novo cervical dystonia patients after injections with 500 U botulinum toxin A (Dysport). BMJ Open 2013;3:e001853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hefter H, Kupsch A, Mungersdorf M, et al. ; on behalf of the Dysport Cervical Dystonia Study Group. A botulinum toxin A treatment algorithm for de novo management of torticollis and laterocollis. BMJ Open 2011;2:e000196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller J, Wissel J, Kemmler G, et al. Craniocervical dystonia questionnaire (CDQ-24): development and validation of a disease-specific quality of life instrument. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:749–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.