Abstract

Objective

Railway workers performing maintenance work of trains and tracks could be at risk of developing noise-induced hearing loss, since they are exposed to noise levels of 75–90 dB(A) with peak exposures of 130–140 dB(C). The objective was to make a risk assessment by comparing the hearing thresholds among train and track maintenance workers with a reference group not exposed to noise and reference values from the ISO 1999.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

A major Norwegian railway company.

Participants

1897 and 2730 male train and track maintenance workers, respectively, all exposed to noise, and 2872 male railway traffic controllers and office workers not exposed to noise.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the hearing threshold (pure tone audiometry, frequencies from 0.5 to 8 kHz), and the secondary outcome was the prevalence of audiometric notches (Coles notch) of the most recent audiogram.

Results

Train and track maintenance workers aged 45 years or older had a small mean hearing loss in the 3–6 kHz area of 3–5 dB. The hearing loss was less among workers younger than 45 years. Audiometric notches were slightly more prevalent among the noise exposed (59–64%) group compared with controls (49%) for all age groups. They may therefore be a sensitive measure in disclosing an early hearing loss at a group level.

Conclusions

Train and track maintenance workers aged 45 years or older, on average, have a slightly greater hearing loss and more audiometric notches compared with reference groups not exposed to noise. Younger (<45 years) workers have hearing thresholds comparable to the controls.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of the study.

The size of the study with a close to 100% participation rate.

The use of two groups for comparison.

High quality of the audiometric data and exposure assessment.

Cross-sectional study with only the most recent audiogram from the participants.

Introduction

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) accounts for more than 60% of occupational disorders reported to the Norwegian Labor Inspection Authority.1 Age is, however, the main cause of hearing loss.2 Heritability, gender, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol level, the use of ototoxic medication and exposure to ototoxic chemicals may also affect the hearing and so may leisure time noise, first and foremost from the use of firearms.3–5

Train and track maintenance workers are occupationally exposed to noise. Noise measurements in the railway companies that we have studied reveal average 8 h noise exposure levels of 75–90 dB(A) in both groups with peak exposures reaching 130–140 dB(C).

In studies of train and track maintenance workers, NIHL has been described by Virokannas,6 but the exposure levels were much higher than in our study. In the US National Health Interview Survey, railroad employees had the highest prevalence of hearing difficulties among the occupational groups examined, but the study did not present audiometric data, only self-reported symptoms.7

Norwegian physicians are legally obliged to report occupational diseases, such as NIHL, to the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. More than 70% of the male 20–64-year-old workers that we have studied, have an audiogram meeting the national criteria for NIHL, namely a sufficiently strong noise exposure and a hearing loss of 25 dB or more at 3, 4 or 6 kHz, worse ear, or 20 dB for all of the 3, 4 and 6 kHz, worse ear, not adjusted for age or sex.8

A recent study of hearing status among train drivers and train conductors in the Norwegian State Railways showed a normal mean hearing threshold for their age.9 Still many of them, just like the maintenance workers that we have studied, had audiograms compatible with the Norwegian criteria for NIHL.

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to assess the risk of NIHL among train and track maintenance workers by comparing their audiograms with audiograms from a reference group of railway workers not exposed to noise and a Norwegian reference population (HUNT),10 which has recently been included in the 2013 revision of the ISO 1999 reference database.11

Methods

Exposure assessment

As a part of the risk assessment of train and track maintenance workers, the occupational hygienists of the occupational health service (OHS) have conducted an extensive programme of measurements of the noise exposure by dosimetry and peak noise measurements. The exposure shows high variability, depending on the type of work being done. On an 8 h average level, the exposure varies from 75 dB(A) up to 90 dB(A), averaging 85–86 dB(A), and with peak exposures up to 130 dB(C)–140 dB(C). Since workers should wear hearing protection when the exposure exceeds 85 dB(A), the actual exposure to the ear will become somewhat lower.

The study group

Most of the train and track maintenance workers have to perform an audiometric test as a part of a mandatory health assessment due to national and European Union regulations for railway safety personnel in order to be certified. The test is to be conducted before employment and later, depending on age, with 1–5-year intervals. All the tests are conducted by the OHS of the Norwegian state railways (NSB).

The most recent available audiograms of the participating subjects, recorded during the period 1994–2011, were obtained from the electronic medical records along with age, sex and type of job information. Since there were only a few female maintenance workers, only male workers were used in the analysis.

Audiograms from train and track maintenance workers were compared with those of a control group of non-exposed male railway office workers, mainly doing traffic controlling, and with a similar social and educational background and salary as the maintenance workers. The study population was also compared with external reference data from the ISO 1999:2013, annex B, table 2, based on a Norwegian reference population.11

Hearing examination

Madsen Xeta Otometrics pure tone audiometric testing using a TDH-39P earphone headset in a soundproof booth at frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz was performed by trained nurses. The audiometric test was conducted in line with standard procedures according to the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority.8 The audiometer was calibrated every second year according to the requirements of the equipment provider.

Since grouped median and percentile values from the better ear are used in the ISO 1990:2013, the same values of the hearing threshold of frequencies from 0.5 to 8 kHz were computed and compared with values from reference groups.

The prevalence of notches was calculated since audiometric notches are regarded as an indicator of NIHL.12 The Coles notch was used. It is defined as hearing thresholds at 3, 4 or 6 kHz of 10 dB or more compared with those at 1 or 2 and 8 kHz.13 The criteria established by Coles et al have been proven to correlate well with clinical assessments.14

Finally, the prevalence of hearing loss meeting the Norwegian NIHL criteria, a hearing loss of 25 dB or more at either 3, 4 or 6 kHz or 20 dB for all of 3, 4 and 6 kHz, worse ear was computed and compared with that in the reference group.

Ethical considerations

The audiograms have been obtained as a part of regular OHSs work. Risk assessment of NIHL is a part of the OHS tasks. Therefore, an application to the regional ethical committee is not necessary according to Norwegian regulations.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used in this study. Groups were compared using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. The data analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics V.20) with percentile values estimated by the FREQUENCIES/GROUPED command.15 A significance level of 5% was chosen.

Results

Audiograms from 1897 train and 2730 track maintenance workers, all males, were compared with audiograms from 2872 male railway office workers working as traffic controllers or in other types of jobs without any significant noise exposure.

An overview of age distribution in train and track maintenance workers and non-exposed office workers is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Background data and noise exposure in male train and track maintenance workers compared with an internal male non-noise exposed reference group

| Age | Train maintenance | Track maintenance | Internal reference | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.6 (11.9) | 46.2 (13.0) | 45.7 (11.8) | <0.001* |

| Age, N | ||||

| −24 | 118 | 286 | 129 | |

| 25–34 | 225 | 275 | 504 | |

| 35–44 | 330 | 529 | 692 | |

| 45–54 | 555 | 801 | 738 | |

| 55–64 | 669 | 839 | 809 | |

| Total | 1897 | 2730 | 2872 | |

| Occupational noise exposure (dB(A)) | 75–90+peak | 75–90+peak | <70 |

*Analysis of variance.

The average age and the distribution of age were similar in the three groups. The noise exposure of train and track maintenance workers is in the order of 75–90 dB(A). In addition, there may be peak exposures of 130–140 dB(C). Hearing protection in terms of ear muffs or ear plugs is to be used when the noise exposure exceeds 80 dB(A).

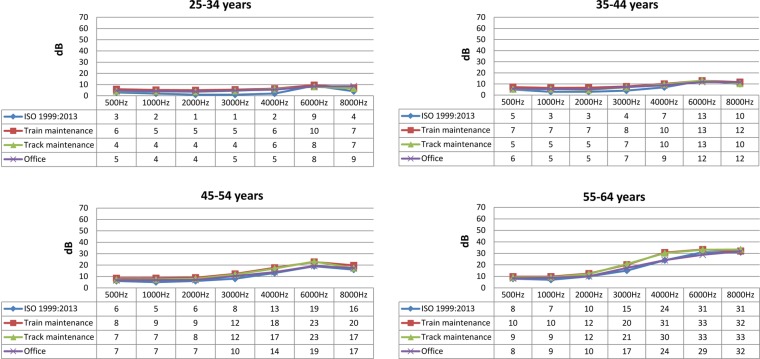

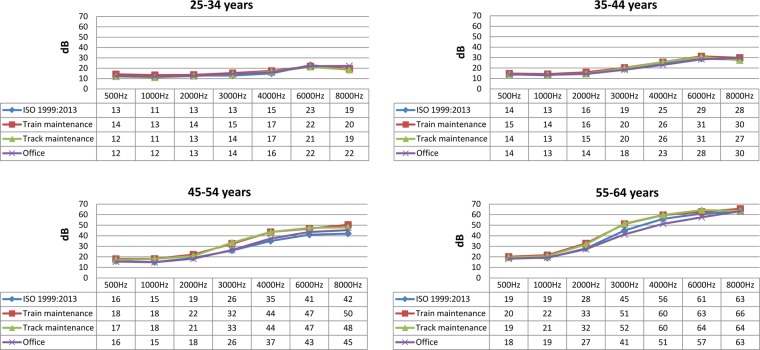

Figure 1 shows the grouped median values of the hearing thresholds of the maintenance workers, the internal control group and the ISO 1999. The largest difference between the noise exposed and the control groups, 2–7 dB for 3 and 4 kHz, was found for the age group 45 years or older compared with the control groups. The grouped 90 centile (figure 2) of the hearing thresholds reveals similar findings with an elevated hearing threshold of 6–10 dB in the same age groups of noise exposed workers compared with control groups. In the younger age groups (25–44 years), there are only minor differences between those with noise exposure compared with those in the internal control group and ISO standards.

Figure 1.

Hearing threshold of male train and track maintenance workers compared with ISO 1999:2013 and an internal reference group of office workers; 50 centile.

Figure 2.

Hearing threshold of male train and track maintenance workers compared with ISO 1999:2013 and an internal reference group of office workers; 90 centile.

The hearing loss and the prevalences of audiometric notches and NIHL criteria in the maintenance workers compared with the internal control group are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Hearing loss (better ear) and prevalence of audiometric notches (worse ear) and NIHL (worse ear) in male train and track maintenance workers compared with an internal male non-noise exposed reference group

| Age | Train maintenance | Track maintenance | Internal reference | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing loss compared with the internal reference, mean 3, 4 and 6 kHz, better ear (95% CI) | ||||

| −24 | 2.3 (0.8 to 3.7) | 1.1 (−0.1 to 2.3)* | 0 (Ref) | |

| 25–34 | 0.8 (−0.5 to 2.1) | 0.0 (−1.2 to 1.3) | 0 (Ref) | |

| 35–44 | 1.8 (0.3 to 3.3) | 1.1 (−0.2 to 2.4) | 0 (Ref) | |

| 45–54 | 3.3 (1.6 to 5.0) | 3.1 (1.5 to 4.6) | 0 (Ref) | |

| 55–64 | 4.6 (2.5 to 6.6) | 4.9 (2.9 to 6.8) | 0 (Ref) | |

| Coles audiometric notch, prevalence, worse ear (%) | ||||

| −24 | 50 | 56 | 39 | <0.001† |

| 25–34 | 50 | 53 | 39 | <0.001 |

| 35–44 | 59 | 62 | 50 | <0.001 |

| 45–54 | 65 | 71 | 55 | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 60 | 66 | 52 | <0.001 |

| Total | 59 | 64 | 49 | <0.001 |

| NIHL criteria hearing loss‡, prevalence, worse ear, (%) | ||||

| −24 | 26 | 21 | 20 | 0.432§ |

| 25–34 | 36 | 29 | 28 | 0.116 |

| 35–44 | 63 | 56 | 50 | <0.001 |

| 45–54 | 87 | 85 | 74 | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 95 | 95 | 92 | 0.005 |

| Total | 76 | 70 | 63 | <0.001 |

*Analysis of variance (ANOVA), Bonferroni post hoc.

†χ2 Test.

‡A hearing threshold of 25 dB or more at 3, 4 or 6 kHz, worse ear, or 20 dB for all of the 3, 4 and 6 kHz, worse ear.

§ANOVA.

From the age of 45, there is a significant hearing loss among maintenance workers of 3–5 dB compared with controls. In the younger age groups, the hearing is comparable with that of the controls group.

An increase in audiometric notches in all groups with increasing age up to the age of 54 and then declining is revealed with significantly higher prevalences in the exposed groups compared with the control group for all age groups.

The prevalence of the Norwegian criteria for NIHL is in line with the audiometric notches found in the present study (table 2), but is only significant for exposed workers compared with controls above 35 years. The prevalence of audiometric NIHL criteria is almost as high in the reference group (63%) as in train and track maintenance workers (70–76%).

The results indicate that there is only a small but significant NIHL in the noise sensitive area (3–6 kHz) in exposed workers from the age of 35.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of 4627 male train and track maintenance workers demonstrates hearing thresholds similar to that of the non-exposed groups, but the oldest workers have a small but significantly greater hearing loss with more notched audiograms than the control group. This indicates a small NIHL in the noise exposed groups. The magnitude of the hearing loss of the noise sensitive area (3–6 kHz) is in the order of 5 dB or less, which is about as expected. According to ISO 1999,11 an unprotected noise exposure of 85 and 90 dB(A) at an 8 h daily basis will lead to a median expected hearing loss of 4 and 9 dB, respectively, after 10 years of exposure.

The hearing of the younger workers is close to normal. This is probably due to the shorter time of noise exposure, better preventive measures, such as the use of noise protection and the use of hearing protection, during the last years and in line with studies of similar noise-exposed groups in the developed world.16–18 Workers aged 45 years or older, however, had a small NIHL. This could be due to the longer time of noise exposure and former high levels of workplace noise. This finding is also in line with previous studies showing that railroad workers are at risk of getting NIHL.6 7

The prevalences of notched audiograms are statistically significantly higher among noise exposed workers compared with controls for all age groups, but only for workers above 35 for the prevalence of the Norwegian NIHL criteria. This may indicate that a notched audiogram is more sensitive than the NIHL criteria in disclosing an early NIHL at a group level. The main problem with both the notched audiograms and the NIHL criteria, however, is the almost as high prevalence of these finding among the controls compared to the exposed. This means that the specificity is low, and these diagnostic criteria for NIHL are therefore of limited value at an individual level.

The strengths of the present study include a large number of maintenance workers and large control groups. We also assess the audiometric measurements to be of good quality. Since audiometric testing is mandatory for most of the workers, we assume that the participation rate is close to100%. The use of two comparison groups strengthens the study. The results from the two comparison groups are very similar. Furthermore, the internal control group of office workers was examined by the same OHS professionals and with the same audiometric equipment as were the train and track maintenance workers.

There are, however, also some limitations of this study.

This cross-sectional assessment is based on only one audiogram from each of the participants, the most recent measurement. Longitudinal data would be favourable in such a study, because selective dropout may have occurred. Since selection in and selection out of work due to hearing loss is quite uncommon, we believe that the limitation of using cross-sectional data in this study is of minor importance.

Information of factors other than noise that may modify hearing loss such as smoking, high blood pressure, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, exposure to ototoxic medication or chemicals, leisure time noise exposure, etc were not available. Thus, the possible confounders were not assessed. The maintenance workers have probably been more exposed to chemicals than the reference groups. For the other factors, we have no reason to believe that they would influence the results since we doubt that they have a different prevalence among workers compared with controls.

Most of the maintenance workers went through a health examination before they were employed, and a severe hearing loss would normally have been regarded as a disqualification preventing employment. One may therefore expect some selection at recruitment. The requirements regarding hearing acuity are not very strict, however, and are identical for the maintenance workers and the control group of railway workers. We therefore believe that selection factors are of minor importance.

We are lacking information of years of employment for maintenance workers and even for office workers. Most of the train and track maintenance workers, however, are recruited at an early age and are quite stable with only a small turnover. The same is the case for the office personnel. We cannot rule out the possibility that these groups have had a previous job with occupational noise exposure, but we assess the possibility for this to influence the results to be unlikely.

Before we conducted this study, there was a general perception that train and track maintenance workers are at risk for getting NIHL. On the basis of individual assessments of workers and their audiograms and using the diagnostic guidelines of the Norwegian Labor Inspection Authority, 70–76% were suspected to have NIHL. The prevalence according to these criteria was 63% in the internal control group with office workers. This indicates that the use of these criteria has strong limitations with respect to the validity of predicting NIHL.

To distinguish between NIHL and age-related hearing loss based solely on audiograms is problematic. Some indications of differences may be given by audiometric notches, but they are also present in workers without any noise exposure as shown in the present and other studies.19 20

The results might be valid for male railway maintenance workers in other countries with similar type of work, noise exposure and legislation.

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study has detected a small average hearing loss among the older part of the 4627 male train and track maintenance workers compared with non-exposed workers in the same company and reference values from ISO 1999:2013.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Per Frode Hove, Ingvill M Hornkjøl and the rest of the staff at the Norwegian State Railways (NSB) Occupational Health Service are greatly acknowledged for providing exposure data, data from the medical records and for valuable criticism and advice.

Footnotes

Contributors: AL and MS have written the first draft of the manuscript. BE and KT have given valuable advice on the manuscript and statistics. TSJ has provided data from the OHS and has also been involved in the drafting of the manuscript. All the authors have given substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising of the article and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Samant Y, Parker D, Wergeland E, et al. The Norwegian Labour Inspectorate's Registry for Work-Related Diseases: data from 2006. Int J Occup Environ Health 2008;14:272–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:879–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Prell CG, Henderson D. Perspectives on noise-induced hearing loss. In: Le Prell CG, Henderson D, Fay RR, et al., eds. Noise induced hearing loss. New York: Springer, 2012:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kvestad E, Czajkowski N, Krog NH, et al. Heritability of hearing loss. Epidemiology 2012;23:328–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tambs K, Hoffman HJ, Borchgrevink HM, et al. Hearing loss induced by noise, ear infections, and head injuries: results from the Nord-Trondelag Hearing Loss Study. Int J Audiol 2003;42:89–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virokannas H, Anttonen H, Niskanen J. Health risk assessment of noise, hand-arm vibration and cold in railway track maintenance. Int J Ind Ergon 1994;13:247–52 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tak S, Calvert GM. Hearing difficulty attributable to employment by industry and occupation: an analysis of the National Health Interview Survey—United States, 1997 to 2003. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority. Audiometric testing in noise exposed workers (in Norwegian). 2013

- 9.Lie A, Skogstad M, Johnsen TS, et al. Hearing status among Norwegian train drivers and train conductors. Occup Med (Lond) 2013;63:544–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engdahl B, Tambs K, Borchgrevink HM, et al. Screened and unscreened hearing threshold levels for the adult population: results from the Nord-Trondelag Hearing Loss Study. Int J Audiol 2005;44:213–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Organization for S. ISO 1999. Acoustics—estimation of noise-induced hearing loss. International Standard 2013;1999: 2013 (E)(1)

- 12.McBride D, Williams S. Characteristics of the audiometric notch as a clinical sign of noise exposure. Scand Audiol 2001;30:106–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coles RR, Lutman ME, Buffin JT. Guidelines on the diagnosis of noise-induced hearing loss for medicolegal purposes. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2000;25:264–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinowitz PM, Galusha D, Slade MD, et al. Audiogram notches in noise-exposed workers. Ear Hear 2006;27:742–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyndman RJ, Fan Y. Sample quantiles in statistical packages. Am Statistician 1996;50:361–5 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubak T, Kock SA, Koefoed-Nielsen B, et al. The risk of noise-induced hearing loss in the Danish workforce. Noise Health 2006;8:80–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruehl P, Ivarsson A, Toremalm NG. Noise-induced hearing loss in an automobile sheet-metal pressing plant. Scand Audiol 1994;23:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engdahl B, Tambs K. Occupation and the risk of hearing impairment—results from the Nord-Trondelag study on hearing loss. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:250–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nondahl DM, Shi X, Cruickshanks KJ, et al. Notched audiograms and noise exposure history in older adults. Ear Hear 2009;30:696–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osei-Lah V, Yeoh LH. High frequency audiometric notch: an outpatient clinic survey. Int J Audiol 2010;49:95–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.