Abstract

Mechanical stress regulates development by modulating cell signaling and gene expression. However, the cytoplasmic components mediating mechanotransduction remain unclear. In this study, elimination of muscle contraction during chicken embryonic development resulted in a reduction in the activity of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the cartilaginous growth plate. Inhibition of mTOR activity led to significant inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation, cartilage tissue growth, and expression of chondrogenic genes, including Indian hedgehog (Ihh), a critical mediator of mechanotransduction. Conversely, cyclic loading (1 Hz, 5% matrix deformation) of embryonic chicken growth plate chondrocytes in 3-dimensional (3D) collagen scaffolding induced sustained activation of mTOR. Mechanical activation of mTOR occurred in serum-free medium, indicating that it is independent of growth factor or nutrients. Treatment of chondrocytes with Rapa abolished mechanical activation of cell proliferation and Ihh gene expression. Cyclic loading of chondroprogenitor cells deficient in SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (Shp2) further enhanced mechanical activation of mTOR, cell proliferation, and chondrogenic gene expression. This result suggests that Shp2 is an antagonist of mechanotransduction through inhibition of mTOR activity. Our data demonstrate that mechanical activation of mTOR is necessary for cell proliferation, chondrogenesis, and cartilage growth during bone development, and that mTOR is an essential mechanotransduction component modulated by Shp2 in the cytoplasm.—Guan, Y., Yang, X., Yang, W., Charbonneau, C., Chen, Q. Mechanical activation of mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is required for cartilage development.

Keywords: mechanotransduction, mTOR, chondrocyte, Shp2

Mechanical signals regulate cartilage homeostasis, not only during fracture healing and joint repair in adults, but also during endochondral bone formation in development (1–3). It has been suggested that mechanical loading regulates the rate of chondrocyte proliferation, maturation, and hypertrophy (4–7). During embryonic development, mechanical loading of growth plate cartilage due to spontaneous muscle contraction profoundly influences the rate of bone growth, as evidenced by the significant reduction of chondrocyte proliferation in the growth plate when muscle contraction was eliminated by midgestation chemical paralysis in chicken embryos (8).

Cellular perception and transduction of mechanical signal within cartilaginous tissues are important modulators of chondrocyte function. Mechanical forces trigger cellular responses that involve different types of receptors through multiple intracellular signaling pathways (3, 6). Chondrocyte mechanoreceptors have been proposed to incorporate integrins, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), and mechanosensitive ion channels. They function in a concerted manner to maintain the chondrocyte phenotype, prevent chondrocyte apoptosis, and regulate chondrocyte differentiation (9–11). However, much is still unknown about the identity of the intracellular multiprotein complexes that transduce mechanical signals in the cytoplasm.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central controller of organ growth and development by functioning as a sensor of growth factors, stress, energy status, oxygen, and amino acids in many major cellular processes (12). mTOR is an atypical serine/threonine protein kinase that interacts with several proteins to form 2 distinct multicomponent signaling complexes, named mTORC1 and mTORC2 (13–16). mTORC1 is the better characterized of these two complexes, which integrates inputs from various signals and modulates many major processes, including protein and lipid synthesis and autophagy (12, 16, 17). When mTORC1 is activated, it phosphorylates p70S6Kinase and 4E-BP1 translation-initiation factor, which are by far the best characterized substrates of mTORC1. They further activate the downstream targets of ribosomal proteins S6 and EIF4E, which in turn, promote protein synthesis. Rapamycin (Rapa) is a specific inhibitor of mTORC1, which has been used for understanding the role of mTOR in cellular regulation.

Previous studies have shown that mTOR signaling is essential for bone development by promoting chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Local infusion of Rapa directly into the proximal tibia growth plates of rabbits inhibits overall long-bone growth (18). Intraperitoneal injection of Rapa impairs longitudinal growth in fast-growing rats, and Rapa delays fracture healing by inhibiting cell proliferation and neovascularization in the callus (8, 19). These studies suggest that mTOR signaling plays an important role in cartilage and bone development. However, it remains unknown whether activation of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway is involved in the mechanical stimulation of bone growth.

The SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (Shp2), a widely expressed cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase with two SH2 domains, has been implicated in signaling events downstream of receptors for growth factors, cytokines, and hormones (20, 21). Most important, it has been shown recently that Shp2 plays a critical role in cartilage homeostasis, since its deficiency in chondroid cells, especially in chondroprogenitors at the groove of Ranvier, causes excessive cell proliferation and cartilage tumor formation (22). However, it is not clear whether Shp2 is involved in mechanical activation of chondrogenesis.

In the current study, cyclic loading induced sustained activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in both primary growth plate chondrocytes and ATDC5 chondroprogenitor cells. Furthermore, mTOR activation was necessary for mechanical stimulation of chondrogenesis, chondrocyte proliferation, and cartilage growth both in vitro and in ovo. Shp2 deficiency elevated mTOR activities in chondroprogenitor cells, which sensitized them to undergo chondrogenesis in response to mechanical loading. These results demonstrate that mechanical stimulation of cartilage growth requires activation of mTOR, an essential intracellular mechanotransduction component negatively regulated by Shp2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against actin, phospho-Akt (Ser473, Akt, phospho-p70S6K (Thr389), p70S6 kinase, phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), phospho-S6 (pS6) ribosomal protein (Ser235/236), S6, and Shp2 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antiproliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). IRDye800-labeled anti-mouse and Alexa Fluor 680-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA, USA) and Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA) separately. Reagent-grade chemicals, including human transferrin, sodium selenite, Rapa, and decamethonium bromide (Deca) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

Chicken primary proliferative, prehypertrophic, and hypertrophic chondrocytes were isolated from the proximal tibia growth plate of 17-d-old embryos (Charles River Laboratories, Inc. Wilmington, MA, USA) and cultured in F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). At 95% confluence, the cells were trypsinized and seeded into 3-dimensional (3D) organotypic chondrocyte culture, as described previously (6, 23). Stable Shp2-deficient chondroprogenitor cell lines and their controls were generated by retroviral infection of ATDC5 cells with pSuper (retro/puro)-based shRNA against murine Shp2 (22) and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, human transferrin, sodium selenite, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin.

Mechanical stimulation

Chicken proliferating chondrocytes or ATDC5 cells (106) were cultured in 3D collagen sponges (3). Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were applied to 2- × 2- × 0.25-cm gel foam sponges (Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) presoaked with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS; Life Technologies). After overnight incubation, >80% of the cells had attached to the collagen scaffolding in the sponges. The sponges were stretched in an intermittent pattern (5 or 10% elongation, 60 stretches/min) for different times with a Biostretch device (ICCT Technologies, Markham, ON, Canada). The extent of matrix deformation generated by this device was found to be comparable with in vivo conditions (3). Nonloaded sponges seeded with cells were kept in the same culture condition, with the exclusion of cyclic loading, and used as the control (24). At the indicated mechanical loading duration, sponges were washed thoroughly with HBSS, cut into small pieces, and digested in 0.03% (w/v) collagenase in HBSS at 37°C for 10 min. Chondrocytes were collected by centrifugation for RNA or protein preparations. Rapa was added to the medium at a concentration of 20 nM for 1 h before and during application of mechanical stimulation.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from cells in collagen sponges (23). Total proteins of chicken tibia growth plate were collected by homogenization in RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with proteinase inhibitors (Cell Signaling Technology). Equal amounts of protein lysates were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were detected with a fluorescence scanner (Odyssey; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Quantification of Western blot data was performed with the Odyssey software.

Chick model of midgestation chemical paralysis and secondary muscle atrophy

Fertilized eggs were incubated at 37°C until they reached the appropriate embryonic stage. The eggs were windowed at embryonic day 12 (E12) of incubation, as described previously, with modifications (2, 25). Briefly, 18 embryos were windowed and randomly assigned to 3 groups to receive a paralyzing drug, Deca (1 mg/ml, 0.5 ml vol), Rapa (2.5 μg/g), or an equivalent volume of normal saline for 2 d, followed by a half dose for an additional 2 d. Embryo motility was determined by counting discrete movements of the right hindlimb during a 3 min observation period. At 5 d after the onset of treatment (E17), tibia growth plate cartilage was collected under a dissecting microscope. Proximal tibial growth plates from the right hindlimbs were collected for histologic study, and the growth plates from the left hindlimbs were collected for protein lysates and RNA isolation.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Right hindlimbs were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin, and a frontal sectioning plane passing down the center line of the proximal tibia was defined by marking the resin surface with a fine scalpel blade while the limb was transilluminated under a dissecting microscope. The plane captured the full length of the growth plate cartilage of the tibia in vertical section. Serial sections were cut along this plane in a sliding microtome. For Safranin-O/Fast Green staining, 5 μm paraffin-embedded sections of tibia from mice were counterstained with hematoxylin before being stained with 0.02% aqueous Fast Green for 4 min (followed by 3 dips in 1% acetic acid) and then 0.1% Safranin-O for 6 min. The slides were then dehydrated and mounted with crystal mounting medium. For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized sections were digested with bovine testicular hyaluronidase (0.1 mg/ml in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C and then washed with PBS and treated with peroxidase-quenching solution to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. After the reaction was blocked for 30 min at room temperature, the sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated at room temperature with biotinylated secondary antibodies for 10 min, then with a streptavidin–peroxidase conjugate for 10 min. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Photography was performed with a Nikon microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). PCNA-positive cellular profiles were calculated as the percentage of total counted cellular profiles in the proximal tibia growth plates. Twelve sections from 3 animals were used to perform the PCNA study.

Cell proliferation assay

Chondrocyte proliferation in 3D organotypic chondrocyte culture was measured by the 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, after overnight incubation, 3D chondrocytes were changed to fresh culture medium containing Rapa (20 nM) or vehicle (DMSO) control. The sponges were then mechanically loaded to induce 5% elongation, as mentioned in the description of mechanical stimulation. Nonloaded sponges seeded with cells were used as the control. BrdU solution was added to 3D chondrocytes for 18 h. After mechanical stimulation, collagen sponges with cultured cells were washed in HBSS before digestion with 0.03% (w/v) collagenase in HBSS for 10 min at 37°C. The cells were collected by centrifugation and then resuspended in 450 μl cell culture medium and plated in a 96-well plate (100 μl/well, 4 wells/sponge) followed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The BrdU assay was continued according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm on a Fusion universal microplate reader (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT, USA). The number of cells was also determined by counting with a hemacytometer (American Optical, Buffalo, NY, USA) under a microscope. Experiments were performed using 3 sponges/chamber/group.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA of cultured chondrocytes and embryonic chicken growth plate cartilage was extracted with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Total RNA (1 μg) from mechanically loaded and nonloaded samples was used for each reverse transcription reaction with the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) by using the QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA (500 ng) from chicken tibial growth plate cartilage was used for cDNA synthesis, and the 18S rRNA was amplified at the same time as an internal control. The PCR profile; the primer sequences used for detecting mRNA level of chicken type II collagen α1 (Col II), Indian hedgehog (Ihh), runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), and SRY-box 9 (Sox9); and the calculations of relative transcript abundance are described elsewhere (23). The following sequence-specific primers were synthesized: Gallus mTOR, 5′-GACCTTGCCAAACTGCTGTG-3′ and 5′-TAATTGCCATCAAGGCCCGT-3′; mouse Col II 5′-TGGTGGAGCAGCAAGAGCAA-3′ and 5′-CAGTGGACAGTAGACGGAGGAAA-3′; mouse Ihh, 5′-GCTCGTGCCTCTTGCCTACA-3′ and CGTGTTCTCCTCGTCCTTGA-3′; mouse polo-like kinase 1 (Plk-1), 5′-CCGCCTCCCTCATCCAGAAG-3′ and 5′-GCGGGGATGTAGCCAGAAGTG-3′; and mouse parathyroid hormone-related protein (Pthrp), 5′-CCCCCAACTCCAAACCTGCTC-3′ and 5′-CCGGGTGTCTTGAGTGGCTGT-3′. For each gene, 3 independent PCRs from the same reverse transcription sample were performed. The presence of a single specific PCR product was verified by melting-curve analysis and confirmed on an agarose gel.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as means ± sd. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey's test were performed in R software to determine significant differences (P<0.05 or P<0.01) in the levels of genes of interest.

RESULTS

Elimination of mechanical stimulation or mTOR activation inhibited cartilage growth and chondrocyte proliferation

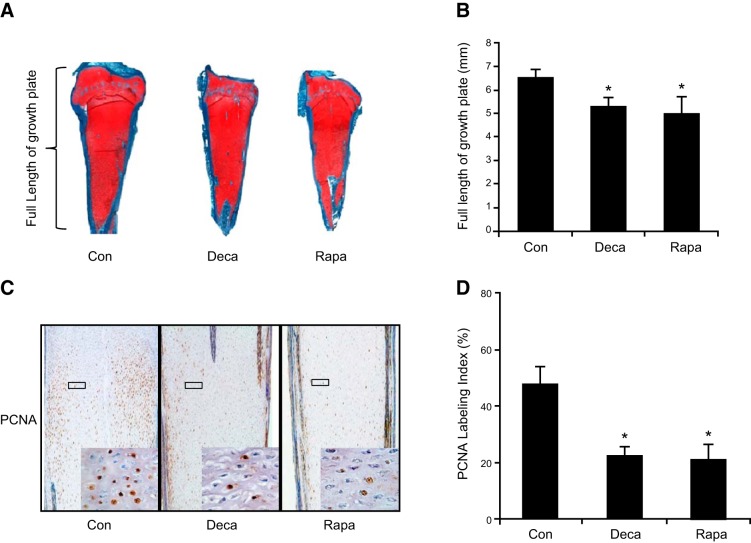

We have shown that local infusion of the mTOR inhibitor Rapa disrupts cartilage growth plate development in young rabbits (18). To determine the role of muscle contraction and mTOR signaling in cartilage during chicken embryonic development, we injected Deca, a muscle-paralyzing agent, or the mTOR inhibitor Rapa in ovo. Deca or Rapa injection resulted in a smaller tibiotarsal growth plate, as evidenced by the significant reduction of the length of cartilaginous tissue (Fig. 1A, B), although they did not alter the overall structure of the growth plate cartilage (Fig. 1A). To determine whether cell proliferation was affected, immunohistochemical analysis of PCNA, an antigen expressed in the nuclei of cells during the DNA synthesis phase of the cell cycle, was performed. Muscle paralysis with Deca or inhibition of mTOR activity with Rapa significantly reduced the number of PCNA-positive cells in the proliferative zone of the tibiotarsal growth plate (Fig. 1C), resulting in a 46.8 ± 6.6 and a 43.9 ± 10.9% reduction of the PCNA labeling index in the muscle paralysis groups and the mTOR inhibition groups relative to their controls, respectively (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Elimination of mechanical stimulation inhibited cartilage growth and chondrocyte proliferation. A) Tibiotarsal growth plate cartilage isolated from E17 chicken embryos injected with Deca, Rapa, or saline (Con), after routine histological processing, sectioning, and staining with safranin O. B) The whole length of the tibiotarsal growth plate was shorter in the Deca and Rapa treatment groups than in the saline control group. Data are means ± sd for n = 6/group. C) Immunohistochemical staining of PCNA in the proliferation zone. Brown staining indicates positive signals of proliferating chondrocytes. Inset: higher magnification micrograph (×400) of the corresponding boxed areas, which indicate the nuclear staining of PCNA. D) PCNA labeling index was calculated by the percentage of PCNA-positive nuclei/total nuclei in the proliferation zone of growth plates. Results are shown as means ± sd from 6 tibiae. *P < 0.05 vs. normal-saline–treated control.

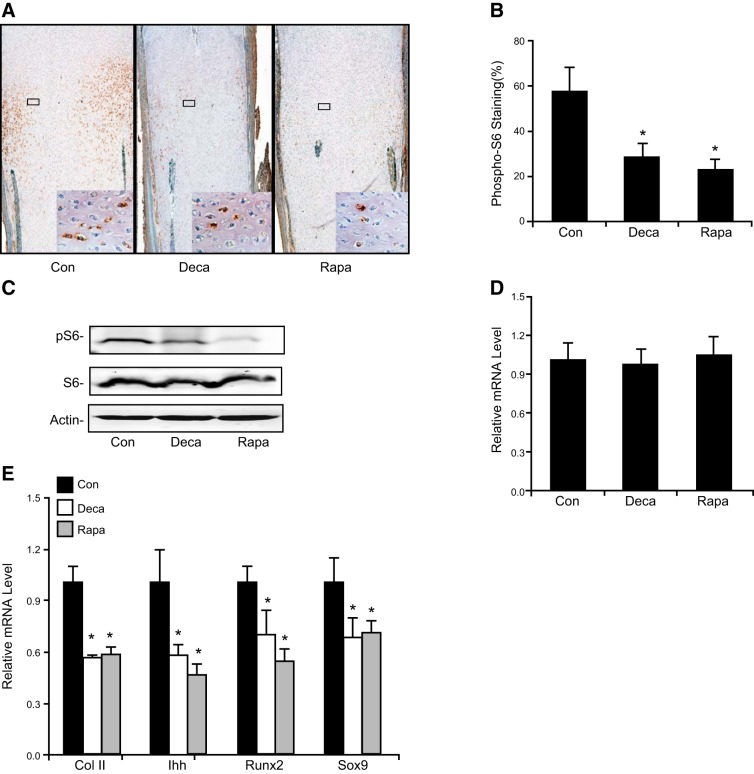

Elimination of mechanical stimulation inhibited mTOR activity and chondrogenic gene expression in growth plate cartilage in ovo

To determine whether inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation and cartilage growth in the muscle paralysis group is due to attenuation of mTOR activity in chondrocytes, we quantified the phosphorylation of ribosome protein S6 on Ser235/236 in embryonic growth plates by immunostaining and Western blot analysis. Phosphorylation of these two sites is generally accepted as a downstream readout for mTOR signaling activation. Indeed, there was a significant reduction of both the number of pS6-positive chondrocytes (Fig. 2A, B) and the phosphorylation of S6 protein isolated from cartilaginous growth plates after muscle paralysis (Fig. 2C). Notably, Rapa treatment of chicken embryonic growth plate cartilage replicated these findings (Fig. 2A–D). Neither the S6 protein level nor the mTOR transcripts were altered as a result of muscle paralysis (Fig. 2C, D). Furthermore, the expression of the chondrogenic marker genes SOX9, Col II, Ihh, and Runx2 in growth plate cartilage was significantly compromised by muscle paralysis or by mTOR inhibition (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that mechanical loading influences chondrogenesis and cartilage growth, most likely via the activation of the mTOR signaling pathway.

Figure 2.

Elimination of mechanical stimulation inhibited mTOR activity and down-regulated chondrogenic gene expression in ovo. A) Immunohistochemical staining of pS6 in the proliferation zone. Brown staining indicates positive signals of pS6 (mTOR activity). Tibiotarsal growth plate cartilage was isolated from E17 chicken embryos injected with Deca, Rapa, or saline control (Con), and subjected to routine histologic processing, sectioning, and immunohistochemical staining with an antibody against pS6. Inset: higher-magnification micrographs (×400) of the corresponding boxed areas, which indicate the cytoplasmic and perinuclear staining of pS6. B) Quantification of pS6 staining is shown as the percentage of pS6-positive cells/total cell nuclei in the proliferation zone of growth plates. C) Western blot analysis of tissue lysates extracted from E17 tibiotarsal growth plates after chick embryos were treated with Deca, Rapa, or saline (normal control). Equal amounts of protein were immunoblotted with antibodies against pS6, total S6, or actin antibodies. D, E) mRNA levels of mTOR (D) and Col II, Ihh, Runx2, and Sox9 (E) in tibia growth plate cartilage were determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from tibia growth plate cartilage from E17 embryos, followed by cDNA synthesis. The mRNA levels of Col II, Ihh, Runx2, Sox9, and mTOR relative to the saline-treated group are shown as means ± sd (n=6). *P < 0.01 vs. saline-treated control.

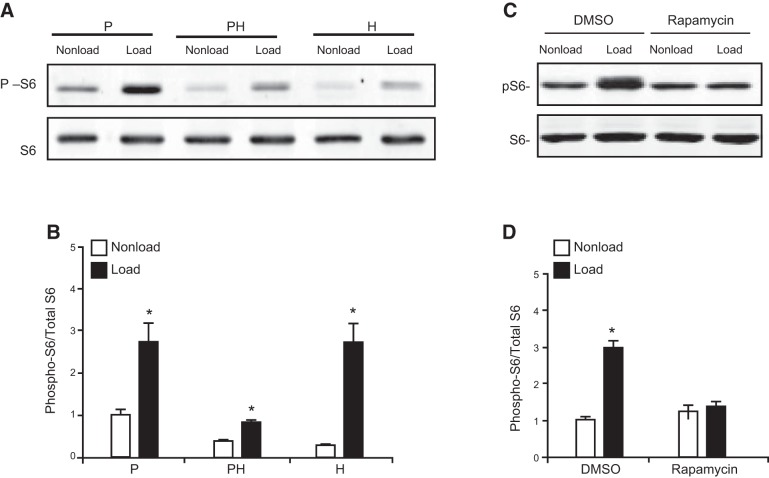

Mechanical loading activated the mTOR signaling pathway in primary growth plate chondrocytes

To gain more insight about the molecular mechanism through which mechanical loading regulates the mTOR pathway in growth plate chondrocytes, we isolated primary chondrocytes from the proliferative, prehypertrophic, and hypertrophic zones in the proximal tibiotarsal growth plate of chicken embryos and characterized their response to mechanical signaling in vitro. Primary chondrocytes from each zone were seeded into 3D collagen scaffolding and subjected to cyclic loading (5% matrix deformation, 1 Hz) for 24 h. Phosphorylation of S6 was examined by Western blot analysis. Cyclic loading significantly increased phosphorylation of S6 in all the developmental stages of chondrocytes. Among them, the highest basal activity and the greatest mechanical response was observed in the proliferating chondrocytes (Fig. 3A). Pretreatment of growth plate chondrocytes with the specific mTOR inhibitor Rapa (20 nM) completely abolished the cyclic-loading-induced phosphorylation of S6 (Fig. 3C, D) Rapa did not block the phosphorylation of S6 at basal level, indicating that another Rapa-insensitive kinase is responsible for this modification. Collectively, these results indicate that cyclic loading induces activation of the mTOR pathway in growth plate chondrocytes. To further study the mechanism of mTOR activation by mechanical signaling, we focused on the proliferating chondrocytes in the following experiments.

Figure 3.

Mechanical loading activated mTOR signaling in growth plate chondrocytes, and the activation was abolished by Rapa. A) Western blot analysis of the levels of pS6 and total S6 protein extracted from primary chondrocytes cultured in 3D collagen scaffolding under cyclic loading (1 Hz, 5% matrix elongation) or static conditions (nonloaded) for 6 h. Cells were isolated from the proliferative (P), prehypertrophic (PH), and hypertrophic (H) zones of the tibiotarsal growth plate of E17 chicken embryos. B) Level of S6 activity (phosphorylated S6 band densities normalized to those of the total S6 protein) in chondrocytes under loaded or nonloaded conditions (means± sd from 3 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. static control cells. C) Western blot analysis of the level of phosphorylated S6 and total S6 protein. Proliferating chondrocytes were pretreated with Rapa (20 nM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 1 h, followed by cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5% elongation for 24 h. D) Level of S6 activity (pS6 band densities normalized to those of the total S6 protein) in chondrocytes under loaded or nonloaded conditions (means± sd from 3 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. nonloaded controls.

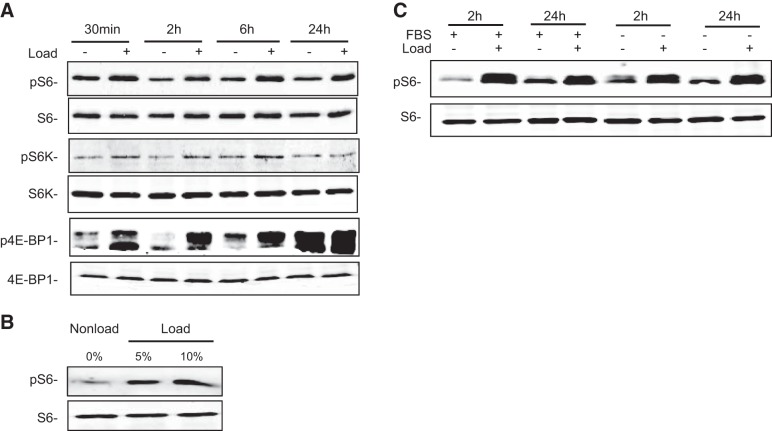

Mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway depended on loading amplitude and length of time but was independent of growth factors and nutrients

To further determine the time course of mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway, primary proliferative chondrocytes were subjected to cyclic loading (5% matrix deformation, 1 Hz) in 3D culture for 30 min and 2, 6, or 24 h. Phosphorylation of the key components of the mTOR pathway, including S6, p70S6 kinase, and 4E-BP1, were examined by Western blot analysis. Cyclic loading induced phosphorylation of these molecules as early as 30 min, and the activation was sustained for the 24 h loading period (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cyclic loading did not change the total protein levels of S6 and p70S6K (Fig. 4A). The chondrocytes subjected to cyclic loading that induced 10% matrix deformation exhibited higher levels of phosphorylated S6 than those with loading of 5% deformation (Fig. 4B). Therefore, activation of mTOR was dose dependent on the amplitude of cyclic loading. To determine whether mTOR activation was dependent on the presence of growth factors or nutrients in serum, we applied cyclic loading of primary proliferative chondrocytes in the presence or absence of serum. Depletion of FBS did not affect mechanical stimulation of S6 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway was dependent on the loading amplitude and length of time but was independent of growth factors and nutrients. A) Western blot analysis of pS6, total S6 protein, P70S6K (pS6K), S6K, p4EBP1, and 4EBP1 from protein extracts of primary proliferating chondrocytes cultured in 3D under loaded (cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5% matrix elongation) or nonloaded conditions for 0.5, 2, 6, or 24 h. B) Activation of the mTOR pathway is dependent on mechanical loading amplitude. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated S6 and total S6 protein extracted from primary proliferative chondrocytes cultured in 3D collagen scaffolding under loaded (cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5 or 10% elongation) or nonloaded conditions for 6 h. C) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated S6 and total S6 protein extracted from primary proliferative chondrocytes cultured in F12 supplemented with or without 10% FBS under loaded or nonloaded conditions for 2 or 24 h.

Mechanical activation of cell proliferation and Ihh gene expression depended on the mTOR activity

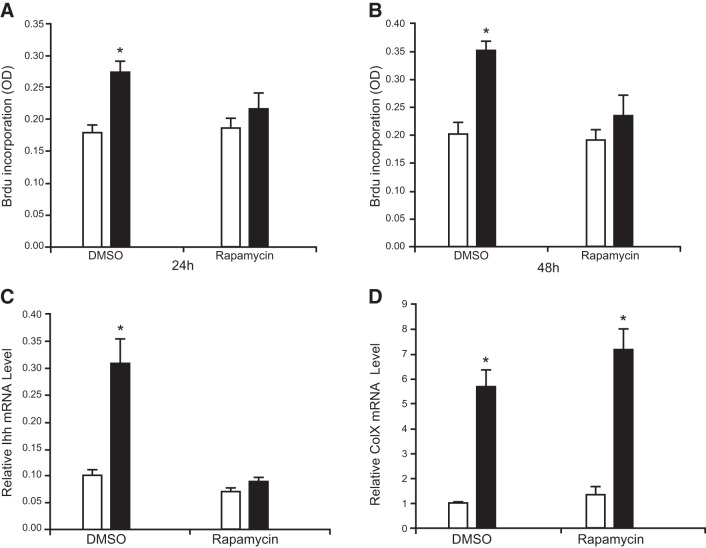

To investigate whether the mTOR activity was necessary for mechanical stimulation of chondrocyte proliferation, we quantified the rate of cell proliferation with BrdU incorporation. Cyclic loading of proliferative chondrocytes for 24 and 48 h resulted in a significant increase in BrdU-positive cells (52.8±3.2 and 75±4.5%, respectively; Fig. 5A, B; DMSO). Pretreating chondrocytes with 20 nM Rapa abolished mechanical stimulation of chondrocyte proliferation (Fig. 5A, B; Rapa).

Figure 5.

Mechanical activation of cell proliferation and Ihh gene expression depended on mTOR activity. A, B) BrdU incorporation index of the primary proliferative chondrocytes cultured under loaded (cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5% matrix elongation) or nonloaded conditions for 24 h (A) or 48 h (B) after pretreatment with Rapa (20 nM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 1 h. Chondrocytes were cultured for 18 h in labeling medium containing BrdU, which became incorporated into the replicating DNA in place of thymidine. Immunodetection of BrdU using specific monoclonal antibodies allows labeling of proliferating cells. Magnitude of the absorbance of the developed color, which is proportional to the quantity of BrdU incorporated into the cells, is shown as means ± sd of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.01 vs. corresponding nonloaded control. C, D) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the mRNA levels of Ihh (C) and Col X (D) of the primary proliferative chondrocytes cultured under loaded (cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5% matrix elongation) or nonloaded conditions for 6 h after pretreatment of Rapa (20 nM) or vehicle control (DMSO) for 1 h. Results are shown as means ± sd (n=3). *P < 0.01 vs. corresponding nonloaded control. Cells were collected after digestion of sponges, and total RNA was extracted, followed by cDNA synthesis.

We have shown in other studies that Ihh, a marker of prehypertrophic chondrocytes, and type X collagen α1 (Col X), a marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, were mechanosensitive genes (6, 10). To investigate whether mechanical activation of these genes depends on the mTOR activity, the abundance of Ihh and Col X transcripts was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Cyclic loading increased the mRNA levels of Ihh and Col X, and Rapa treatment abolished mechanical induction of Ihh mRNA levels (Fig. 5C). However, pretreatment of chondrocytes with Rapa did not affect mechanical up-regulation of Col X mRNA levels (Fig. 5D).

Deficiency of tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 sensitized mechanical stimulation of mTOR and chondrogenesis

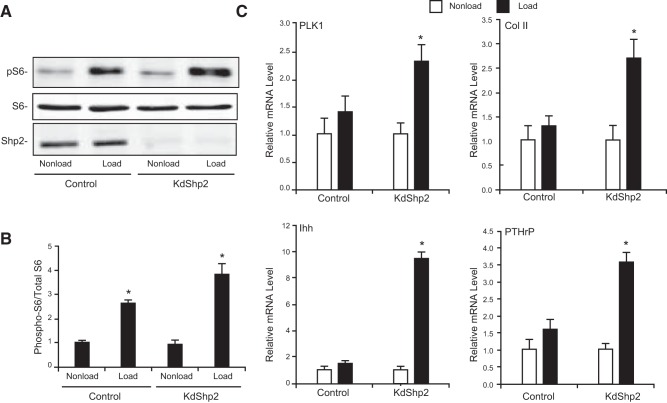

To determine whether mechanical activation of mTOR was modulated by Shp2, we quantified the mTOR activity in the Shp2-deficient ATDC5 chondroprogenitor cells in response to cyclic loading in 3D culture. More than 90% of Shp2 protein was knocked down with short-hairpin RNA against murine Shp2 in ATDC5 chondroprogenitors (Fig. 6A, KdShp2). Cyclic loading significantly increased the phosphorylation of S6 in control ATDC5 cells (Fig. 6A, control), consistent with the pattern of mechanical activation of primary growth plate chondrocytes. Interestingly, The Shp2-deficient ATDC5 cells showed a higher level of mechanical activation of pS6 than did the control cells (Fig. 6A, B).

Figure 6.

Deficiency of tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 sensitizes mechanical stimulation of mTOR (A, B) and chondrogenesis (C). A) Western blot analysis of pS6, total S6 protein, and Shp2 in chondroprogenitor ATDC5 cell (control) or Shp2-deficient ATDC5 cells (KdShp2). Knocking down Shp2 in chondroprogenitor cells enhanced mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway. Cells seeded into 3D collagen scaffolding were cultured under loaded (cyclic loading at 1 Hz, 5% matrix elongation) or nonloaded conditions for 48 h. B) Level of S6 activity (phosphorylated S6 band densities normalized to those of the total S6 protein) in ATDC5 cells under loaded or nonloaded conditions (means ± sd of results in 3 independent experiments). *P < 0.05 vs. nonloaded controls. C) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of chondrogenesis markers, including Col II, Ihh, Pthrp, and Plk1, in control ATDC5 cells or Shp2-deficient ATDC5 cells (KdShp2). Total RNA was extracted from the cells cultured in 3D under loaded or nonloaded conditions, followed by cDNA synthesis. Data are means ± sd (n=3). *P < 0.01 vs. nonloaded controls.

To determine whether Shp2 deficiency affects mechanical stimulation of cell proliferation and chondrogenesis, we used the mRNA level of Plk1, an early trigger for G2/M transition as an indicator of cell proliferation (26, 27), and the mRNA levels of chondrogenesis marker genes, including Col II, Ihh, and Pthrp, were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Cyclic loading of ATDC5 chondroprogenitor cells increased the mRNA levels of Plk1, Col II, Ihh, and Pthrp. However, the increases were not statistically significant (Fig. 6C). Deficiency of Shp2 greatly increased the extent of mechanical stimulation of all 4 genes, compared with that in their nonloaded control. Thus, knockdown of Shp2 enhanced mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway and sensitized mechanical stimulation of cell proliferation and chondrogenesis in chondroprogenitor cells.

DISCUSSION

The longitudinal growth of long bones occurs in the growth plates, where chondrocytes synthesize a cartilaginous tissue that is subsequently ossified. It is known that bone growth and remodeling can be modulated by mechanical stress (28, 29). For example, application of mechanical loading has been used to stimulate bone formation in clinical procedures such as distraction osteogenesis, whereas a lack of joint movement results in skeletal deformities such as arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (30–32). A landmark study by Hall and Herring (33) revealed that paralysis affects bone growth in the embryonic chick. However, the underlying molecular mechanism is unknown. In the current study, we uncovered a novel mechanism by which mechanical loading induces chondrocyte proliferation and long-bone growth through the activation of the mTOR pathway in growth plate chondrocytes. The mTOR signaling pathway has been shown to play a role in modulating chondrocyte function in response to growth factors, such as insulin, or to nutrition, such as amino acids (25, 34). In the current study, we wanted to determine whether the mTOR pathway is activated by mechanical loading, and if so, what role it plays in the biomechanical modulation of bone growth.

We have shown that cyclic loading is sufficient to activate mTOR activity in growth plate chondrocytes. During development, connected tissues growing at different rates may generate complicated distributions of physical deformations (strains) and pressures (2). Although stress due to growth is quasi-static, stress due to muscular activity is cyclic. To mimic the effect of muscle contraction in vitro, we cultured primary embryonic chondrocytes in 3D collagen scaffolding. Cyclic loading was applied to induce a physiological level of tissue strain in the cartilage (1 Hz, 5% matrix deformation). Our study is the first to show that the mTOR pathway is activated by cyclic loading in growth plate chondrocytes in vitro and in vivo, as well as in chondroprogenitor ATDC5 cells. We discovered 4 characteristics of mechanical activation of mTOR in chondrogenic cells. First, the exposure of chondrocytes to cyclic mechanical stimulation rapidly activated the mTOR signaling pathway (e.g., in minutes). Phosphorylation of mTOR led to its activation and subsequent phosphorylation of p70S6K, S6, and 4E-BP1. Second, mTOR activity was sustained during a longer period of mechanical loading (e.g., for 24 and 48 h). Third, mechanical activation of mTOR activity was dependent on the amplitude of mechanical loading. Most interesting, mechanical activation of mTOR occurred in serum-free medium, suggesting a direct mechanical activation of mTOR activity in cells, rather than an indirect pathway through growth factors and nutrients. Some of these properties of mTOR distinguish it from other second messengers mediating mechanical signals in the cytoplasm, such as Ca2+, which is induced by mechanical loading in seconds in an oscillating manner (35, 36). The characteristics of mechanical activation of mTOR are similar to those of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), such as ERK activation in bone cells by oscillating fluid flow (37). This observation indicates a possible relationship between these signaling pathways in mechanotransduction. Consistent with this hypothesis, application of oscillatory shear stress (OSS) to human osteoblast-like MG63 cells induces sustained activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K (p70S6 kinase) signaling cascades and cell proliferation (38).

We have shown that inhibition of mTOR activity is sufficient to abolish mechanical stimulation of growth plate chondrocytes in vitro and in vivo. In cartilage, mechanotransduction is mediated by so-called mechanosensitive genes. The translational products of these genes comprise the molecular components of the mechanotransduction pathway, including pericellular matrix proteins, which physically link interstitial extracellular matrix with cytoskeleton through membrane receptors (6, 39). In addition, morphogens and growth factors such as Ihh and BMP 2/4 mediate the conversion of mechanical signals into diffusible chemical signals affecting neighboring cells and tissues (10). In our study, inhibiting mTOR activity with Rapa abolished mechanical up-regulation of chondrocyte proliferation and Ihh mRNA levels. These findings suggest that mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway is responsible for mechanical stimulation of chondrocyte proliferation, which has been shown to be mediated by Ihh (10). Thus, Ihh may be a downstream target of mTOR in mechanical activation of chondrocyte proliferation. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been shown that addition of Ihh to the culture medium is sufficient to reverse the effect of Rapa on chondrogenesis (25).

To determine the biological consequence of mTOR activation in mechanical regulation of bone development, we induced muscle paralysis in chicken embryos. Injection of neuromuscular blocking agents into chick embryos is a widely used technique for the study of immobilization during limb development (33, 40–42). Movement in the chick embryo begins at 3.5 d (stages 21–23), but motility in the wings and legs does not occur until 6.5 d (stage 30) (43). It has been shown that muscle contraction is necessary to maintain proliferation and differentiation of the growth plate chondrocytes (41). Our results suggest that the muscle contraction requirement for long-bone growth is mediated by mechanical activation of mTOR activity in growth plate chondrocytes. mTOR activation is essential for mechanical stimulation of chondrocyte proliferation and chondrogenic gene expression. In the absence of muscle contraction, mTOR activity is significantly reduced in the growth plate. As a consequence, the developing limb without muscle contraction mimics that of the limb with normal muscle contraction, but without mTOR activation. The similarities of the two phenotypes are multifold, including the inhibition of mTOR activity, chondrocyte proliferation, cartilage tissue growth, and the expression of chondrogenic genes, including Col II, Ihh, Runx2, and Sox9. These inhibitions are due to the reduction of mTOR activity, rather than to a general suppression of protein synthesis, since the levels of mTOR mRNA and S6 protein remained unchanged in the chondrocytes. Thus, we demonstrated that mechanical activation of mTOR is necessary for maintaining the normal rate of cell proliferation, chondrogenesis, and cartilage growth in endochondral bone formation during embryonic development.

Long-bone growth occurs not only through cell mitosis, but also through ECM production and increased cell size (hypertrophy; refs. 24, 44, 45). It has been proposed that local mechanical cues influence development by modulating not only growth rates but also tissue differentiation (46–50). We showed in another study that cyclic loading not only stimulates the mitosis rate but also the rate of ECM production and cell hypertrophy (6). We showed in the current study that cyclic loading induces mTOR activity in the proliferating, prehypertrophic, and hypertrophic chondrocytes, suggesting that chondrocytes in all differentiation stages of the growth plate can respond to cyclic loading by inducing mTOR activity. However, the highest basal level and the greatest mechanical activation of mTOR activity occur in proliferating chondrocytes, suggesting that mechanical activation of mTOR plays a more prominent role in regulating the properties of proliferating chondrocytes. Indeed, the major phenotype of the growth plate that lacks muscle contraction is the reduction of chondrocyte proliferation and cartilage tissue growth, similar to Rapa-treated, mTOR-deficient growth plate cartilage. In contrast, Rapa treatment of chondrocytes did not suppress mechanical stimulation of Col X mRNA, a marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, which suggests that other mTOR-independent mechanisms account for mechanical stimulation of chondrocyte hypertrophy.

Our data indicate that the effect of mechanical activation of mTOR activity may be different from that of mTOR activation by growth factors or nutrients. It was shown in a prior study that inhibiting mTOR activity in the growth plate affects both chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy (18) and that insulin-induced mTOR activation selectively enhances chondrocyte hypertrophy (25). However, in our study, cyclic loading–activated mTOR mainly stimulated chondrocyte proliferation. Furthermore, inhibiting mechanical activation of mTOR activity did not reduce mechanical activation of Col X mRNA, a marker of chondrocyte hypertrophy. These observations strongly suggest that the mTOR pathway, when activated by mechanical factors, diverges from that activated by growth factors or nutrients. It further suggests differential modulation of mTOR activity in the cytoplasm.

One of the modulators of the mechanical activation of mTOR may be Shp2, a cytoplasmic tyrosine phosphatase. Knockdown of Shp2 in chondroprogenitor cells greatly increased mechanical stimulation of the mTOR signaling pathway and the expression levels of chondrogenesis markers. These data indicate that Shp2 is a negative regulator of mTOR during cellular mechanotransduction. That the level of Shp2 is not altered by cyclic loading suggests that it is the inherent, preexisting Shp2 level in the cytoplasm that determines how sensitive chondroprogenitor cells respond to mechanical signals. This possibility is consistent with the previous finding that Shp2 suppresses mTOR/S6K1 activity under growth factor deprivation conditions (20). Interestingly, Shp2 has been shown recently to be a potent inhibitor of chondrocyte proliferation and chondrogenesis in vivo (22, 51). Furthermore, chondroprogenitor cells populate the groove of Ranvier in the growth plate. The deficiency of Shp2 in these cells results in tumorigenesis, which can be ameliorated by in vivo administration of an Smo/hedgehog inhibitor (22). It is intriguing, as shown in the current study, that both mTOR activation and cell proliferation occur at or around the groove of Ranvier in the embryonic chicken tibiotarsal growth plate. Elimination of cyclic loading by muscle paralysis inhibits mTOR activation, cell proliferation, and activation of Ihh and other chondrogenic gene expression. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that Shp2 inhibits mechanical activation of the mTOR pathway in chondroid cells.

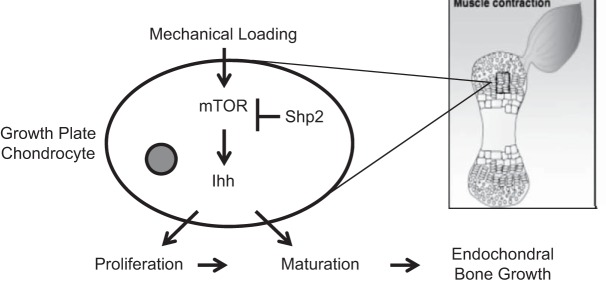

In summary, the current study demonstrated that mTOR is an essential component of the mechanotransduction pathway in cartilage and is necessary for mechanical regulation of embryonic cartilage development in vivo. Based on these data, we hypothesize the existence of an mTOR/Shp2/Ihh axis that mediates mechanotransduction in growth plate cartilage during development (Fig. 7). Our study suggests a model by which a mechanical signal activates mTOR, which induces its downstream target Ihh. Ihh, in turn, regulates proliferation and/or maturation of chondrocytes. Shp2 desensitizes chondrocytes' response to mechanical stimulation by inhibiting the mTOR activation. These findings may have important implications, not only for treating skeletal deformities due to abnormal mechanical loading, but also for cartilage and bone repair with tissue engineering.

Figure 7.

Model of mechanoregulation of growth plate cartilage during embryonic development via the mTOR/Shp2/Ihh axis. During embryonic development, mechanical loading of growth plate cartilage due to muscle contraction profoundly influences the rate of long-bone growth. Our findings demonstrate that activation of the mTOR activity in growth plate chondrocytes by muscle contraction is necessary for mechanical stimulation of cartilage development in vivo. In addition, we propose that this regulation is mediated by the mTOR/Shp2/Ihh axis in growth plate chondrocytes. Our study suggests a model by which an external mechanical signal activates mTOR signaling in chondrocytes, which induces its downstream target Ihh. Ihh, in turn, regulates proliferation and maturation of chondrocytes. Shp2 desensitizes chondrocytes' response to mechanical stimulation by inhibiting mTOR activation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Phornphutkul for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants GM104937 and AG017021) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) of China (grant 81271978).

Footnotes

- 3D

- 3-dimensional

- BrdU

- 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- Col II

- type II collagen α1

- Col X

- type X collagen α1

- Deca

- decamethonium bromide

- E

- embryonic day

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- Ihh

- Indian hedgehog

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- Plk1

- polo-like kinase 1

- pS6

- phosphorylated S6

- Pthrp

- parathyroid hormone-related protein

- Rapa

- rapamycin

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- Runx2

- runt-related transcription factor 2

- Shp2

- SH2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2

- Sox9

- SRY-box 9

REFERENCES

- 1. Kim Y. J., Sah R. L., Grodzinsky A. J., Plaas A. H., Sandy J. D. (1994) Mechanical regulation of cartilage biosynthetic behavior: physical stimuli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 311, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carter D. R., Orr T. E., Fyhrie D. P., Schurman D. J. (1987) Influences of mechanical stress on prenatal and postnatal skeletal development. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 237–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schneiderman R., Keret D., Maroudas A. (1986) Effects of mechanical and osmotic pressure on the rate of glycosaminoglycan synthesis in the human adult femoral head cartilage: an in vitro study. J. Orthop. Res. 4, 393–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sibonga J. D., Zhang M., Evans G. L., Westerlind K. C., Cavolina J. M., Morey-Holton E., Turner R. T. (2000) Effects of spaceflight and simulated weightlessness on longitudinal bone growth. Bone 27, 535–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong M., Siegrist M., Goodwin K. (2003) Cyclic tensile strain and cyclic hydrostatic pressure differentially regulate expression of hypertrophic markers in primary chondrocytes. Bone 33, 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu Q. Q., Chen Q. (2000) Mechanoregulation of chondrocyte proliferation, maturation, and hypertrophy: ion-channel dependent transduction of matrix deformation signals. Exp. Cell Res. 256, 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ueki M., Tanaka N., Tanimoto K., Nishio C., Honda K., Lin Y. Y., Tanne Y., Ohkuma S., Kamiya T., Tanaka E., Tanne K. (2008) The effect of mechanical loading on the metabolism of growth plate chondrocytes. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 36, 793–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alvarez-Garcia O., Carbajo-Perez E., Garcia E., Gil H., Molinos I., Rodriguez J., Ordonez F. A., Santos F. (2007) Rapamycin retards growth and causes marked alterations in the growth plate of young rats. Pediatr. Nephrol. 22, 954–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramage L., Nuki G., Salter D. M. (2009) Signalling cascades in mechanotransduction: cell-matrix interactions and mechanical loading. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 19, 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu Q., Zhang Y., Chen Q. (2001) Indian hedgehog is an essential component of mechanotransduction complex to stimulate chondrocyte proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35290–35296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nowlan N. C., Prendergast P. J., Murphy P. (2008) Identification of mechanosensitive genes during embryonic bone formation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. (2006) TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang Q., Guan K. L. (2007) Expanding mTOR signaling. Cell Res. 17, 666–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loewith R., Jacinto E., Wullschleger S., Lorberg A., Crespo J. L., Bonenfant D., Oppliger W., Jenoe P., Hall M. N. (2002) Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol. Cell 10, 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sarbassov D. D., Ali S. M., Kim D. H., Guertin D. A., Latek R. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Sabatini D. M. (2004) Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 14, 1296–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sparks C. A., Guertin D. A. Targeting mTOR: prospects for mTOR complex 2 inhibitors in cancer therapy. Oncogene 29, 3733–3744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soulard A., Cohen A., Hall M. N. (2009) TOR signaling in invertebrates. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 825–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phornphutkul C., Lee M., Voigt C., Wu K. Y., Ehrlich M. G., Gruppuso P. A., Chen Q. (2009) The effect of rapamycin on bone growth in rabbits. J. Orthop. Res. 27, 1157–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holstein J. H., Klein M., Garcia P., Histing T., Culemann U., Pizanis A., Laschke M. W., Scheuer C., Meier C., Schorr H., Pohlemann T., Menger M. D. (2008) Rapamycin affects early fracture healing in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 1055–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zito C. I., Qin H., Blenis J., Bennett A. M. (2007) SHP-2 regulates cell growth by controlling the mTOR/S6 kinase 1 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6946–6953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dance M., Montagner A., Salles J. P., Yart A., Raynal P. (2008) The molecular functions of Shp2 in the Ras/Mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2) pathway. Cell. Signal. 20, 453–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang W., Wang J., Moore D. C., Liang H., Dooner M., Wu Q., Terek R., Chen Q., Ehrlich M. G., Quesenberry P. J., Neel B. G. (2013) Ptpn11 deletion in a novel progenitor causes metachondromatosis by inducing hedgehog signalling. Nature 499, 491–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guan Y. J., Yang X., Wei L., Chen Q. (2011) MiR-365: a mechanosensitive microRNA stimulates chondrocyte differentiation through targeting histone deacetylase 4. FASEB J. 25, 4457–4466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Q., Johnson D. M., Haudenschild D. R., Goetinck P. F. (1995) Progression and recapitulation of the chondrocyte differentiation program: cartilage matrix protein is a marker for cartilage maturation. Dev. Biol. 172, 293–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phornphutkul C., Wu K. Y., Auyeung V., Chen Q., Gruppuso P. A. (2008) mTOR signaling contributes to chondrocyte differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 237, 702–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stuermer A., Hoehn K., Faul T., Auth T., Brand N., Kneissl M., Putter V., Grummt F. (2007) Mouse pre-replicative complex proteins colocalise and interact with the centrosome. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 37–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spankuch B., Heim S., Kurunci-Csacsko E., Lindenau C., Yuan J., Kaufmann M., Strebhardt K. (2006) Down-regulation of Polo-like kinase 1 elevates drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 66, 5836–5846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robling A. G. (2009) Is bone's response to mechanical signals dominated by muscle forces? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 41, 2044–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forwood M. R. (2001) Mechanical effects on the skeleton: are there clinical implications? Osteoporos. Int. 12, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ji B., Jiang G., Fu J., Long J., Wang H. (2010) Why high frequency of distraction improved the bone formation in distraction osteogenesis? Med. Hypotheses 74, 871–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moore D. C., Leblanc C. W., Muller R., Crisco J. J., 3rd, Ehrlich M. G. (2003) Physiologic weight-bearing increases new vessel formation during distraction osteogenesis: a micro-tomographic imaging study. J. Orthop. Res. 21, 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dane B., Dane C., Aksoy F., Cetin A., Yayla M. (2009) Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita: analysis of twelve cases. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 36, 259–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall B. K., Herring S. W. (1990) Paralysis and growth of the musculoskeletal system in the embryonic chick. J. Morphol. 206, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sengupta S., Peterson T. R., Sabatini D. M. (2010) Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol. Cell 40, 310–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Godin L. M., Suzuki S., Jacobs C. R., Donahue H. J., Donahue S. W. (2007) Mechanically induced intracellular calcium waves in osteoblasts demonstrate calcium fingerprints in bone cell mechanotransduction. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 6, 391–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Donahue S. W., Jacobs C. R., Donahue H. J. (2001) Flow-induced calcium oscillations in rat osteoblasts are age, loading frequency, and shear stress dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C1635–C1641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. You J., Yellowley C. E., Donahue H. J., Zhang Y., Chen Q., Jacobs C. R. (2000) Substrate deformation levels associated with routine physical activity are less stimulatory to bone cells relative to loading-induced oscillatory fluid flow. J. Biomech. Eng. 122, 387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee D. Y., Li Y. S., Chang S. F., Zhou J., Ho H. M., Chiu J. J., Chien S. (2010) Oscillatory flow-induced proliferation of osteoblast-like cells is mediated by alphavbeta3 and beta1 integrins through synergistic interactions of focal adhesion kinase and Shc with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kanbe K., Yang X., Wei L., Sun C., Chen Q. (2007) Pericellular matrilins regulate activation of chondrocytes by cyclic load-induced matrix deformation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pitsillides A. A. (2006) Early effects of embryonic movement: ‘a shot out of the dark.’ J. Anat. 208, 417–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Germiller J. A., Goldstein S. A. (1997) Structure and function of embryonic growth plate in the absence of functioning skeletal muscle. J. Orthop. Res. 15, 362–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lamb K. J., Lewthwaite J. C., Lin J. P., Simon D., Kavanagh E., Wheeler-Jones C. P., Pitsillides A. A. (2003) Diverse range of fixed positional deformities and bone growth restraint provoked by flaccid paralysis in embryonic chicks. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 84, 191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Provine R. R. (1980) Development of between-limb movement synchronization in the chick embryo. Dev. Psychobiol. 13, 151–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mackie E. J., Tatarczuch L., Mirams M. (2011) The skeleton: a multi-functional complex organ: the growth plate chondrocyte and endochondral ossification. J. Endocrinol. 211, 109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pines M., Hurwitz S. (1991) The role of the growth plate in longitudinal bone growth. Poult. Sci. 70, 1806–1814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Villemure I., Stokes I. A. (2009) Growth plate mechanics and mechanobiology: a survey of present understanding. J. Biomech. 42, 1793–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Studer D., Millan C., Ozturk E., Maniura-Weber K., Zenobi-Wong M. (2012) Molecular and biophysical mechanisms regulating hypertrophic differentiation in chondrocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. Cell Mater. 24, 118–135; discussion, 135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Forriol F., Shapiro F. (2005) Bone development: interaction of molecular components and biophysical forces. Clin Orthop. Relat. Res. 14–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Duke P. J., Montufar-Solis D. (1999) Exposure to altered gravity affects all stages of endochondral cartilage differentiation. Adv. Space Res. 24, 821–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Henderson J. H., Carter D. R. (2002) Mechanical induction in limb morphogenesis: the role of growth-generated strains and pressures. Bone 31, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krejci P., Masri B., Salazar L., Farrington-Rock C., Prats H., Thompson L. M., Wilcox W. R. (2007) Bisindolylmaleimide I suppresses fibroblast growth factor-mediated activation of Erk MAP kinase in chondrocytes by preventing Shp2 association with the Frs2 and Gab1 adaptor proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2929–2936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]