Abstract

Blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) is a frequent emergency and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in spite of improved recognition, diagnosis and management. Trauma is the second largest cause of disease accounting for 16% of global burden. The World Health Organization estimates that, by 2020, trauma will be the first or second leading cause of years of productive life lost for the entire world population. This study endeavors to evaluate 71 cases of BAT with stress on early diagnosis and management, increase use of non operative management, and time of presentation of patients. A retrospective analysis of 71 patients of BAT who were admitted in Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences hospital (KIMS, Bangalore, India) within a span of 18 months was done. Demographic data, mechanism of trauma, management and outcomes were studied. Most of the patients in our study were in the age group of 21-30 years with an M:F ratio of 3.7:1. Motor vehicle accident (53%) was the most common mechanism of injury. Spleen (53%) was the commonest organ injured and the most common surgery performed was splenectomy (30%). Most common extra abdominal injury was rib fracture in 20%. Mortality rate was 4%. Wound sepsis (13%) was the commonest complication. Initial resuscitation measures, thorough clinical examination and correct diagnosis forms the most vital part of management. 70% of splenic, liver and renal injuries can be managed conservatively where as hollow organs need laparotomy in most of the cases. The time of presentation of patients has a lot to do with outcome. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can save many lives.

Key words: Blunt abdominal trauma, trauma, spleen, computed tomographic scan, early diagnosis, resuscitation

Introduction

Trauma has been called the neglected disease of modern society, despite its close companionship with man. Trauma is the leading cause of death and disability in developing countries and the most common cause of death under 45 years of age.1 World over injury is the 7th cause of mortality and abdomen is the third most common injured organ. Abdominal injuries require surgery in about 25% of cases. 85% of abdominal traumas are of blunt character.2 The spleen and liver are the most commonly injured organs as a result of blunt trauma. Clinical examination alone is inadequate because patients may have altered mental status and distracting injuries. Initial resuscitation along with focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) and computed tomography (CT) abdomen are very beneficial to detect those patients with minimal and clinically undetectable signs of abdominal injury and are the part of recent management guidelines. Approach to trauma should be systemic and prioritized. About 10% of patients have persistent hypovolemic shock as a result of continuous blood loss in spite of aggressive fluid resuscitation and require an urgent laparotomy. Damage control laparotomy is a life saving procedure for such patients with life-threatening injuries and to control hemorrhage and sepsis. On the other spectrum, there has been increasing trend towards non operative management (NOM) of blunt trauma amounting to 80% of the cases with failure rates of 2-3%.3 NOM is a standard protocol for hemodynamically stable solid organ injuries.

Pre-hospital transportation, initial assessment, thorough resuscitative measures and correct diagnosis are of utmost importance in trauma management.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study of 71 cases of blunt abdominal trauma patients presenting to Kempegowda Institute of medical sciences, Bangalore from May 2009 to November 2010 was done. After initial resuscitation, detailed clinical history, physical examination, laboratory tests and x-rays, ultrasonography (FAST) was done to arrive at the diagnosis. CT scan was done in most of the cases. Patients were categorized to stable vs unstable. The progress of patients was closely monitored and decision was taken to either continue with conservative management or to undertake laparotomy. Patients who did not respond to conservative management and were hemodynamically unstable and continued to deteriorate despite adequate resuscitation or who had evidence of bowel involvement were taken for immediate laparotomy. Inferences were made for various variables like age, sex, cause of blunt abdominal trauma, time of presentation of patient, signs and symptoms, operative findings, various procedures employed, associated extra-abdominal injuries, post operative complications and mortality.

Results

Demographic profile

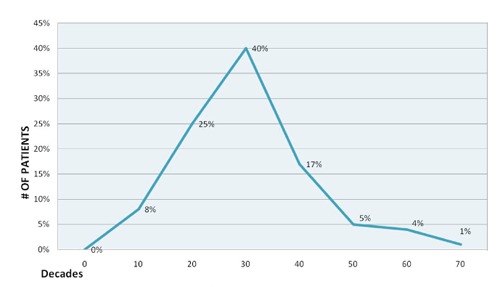

We included 71 blunt trauma patients; 56 (79%) were males and 15 (21%) females; mean age was 25 years. The predominant age group was 21-30 years constituting 40% of patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age distribution of patients.

Epidemiological factors

Road traffic accidents involving both pedestrians and vehicular accidents accounted for 53% majority of injuries (Table1).

Clinical features

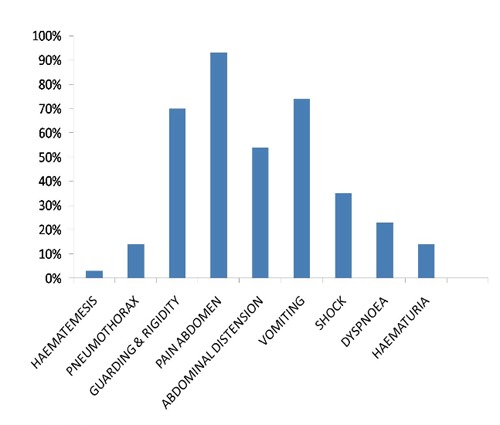

Majority of patients presented with pain abdomen (66) followed by vomiting in 52 patients. Dyspnea was present in 16 patients and hematuria in 8 patients. Among physical signs generalized abdominal tenderness and guarding were present in 50 (70%) patients where as 24 (34%) were in hypovolemic shock (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical features of patients.

Extra-abdominal injuries

Commonly associated extra-abdominal injuries were soft tissue injury including retroperitoneal hematoma 14 (20%), head injury 10 (14%), and hemothorax 10 (14%). Associated orthopedics injuries in our study were mainly rib fractures in 14 (20%) (Table 2). Most of the associated injuries were treated conservatively where as hemothorax and pneumothorax required intercostal drainage.

Table 2.

Associated injuries.

| Sn. | Associated injury | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Head injury | 10 | 14 |

| 2. | Hemothorax | 10 | 14 |

| 3. | Pneumothorax | 4 | 6 |

| 4. | Rib fracture | 14 | 20 |

| 5. | Femur fracture | 7 | 10 |

| 6. | Spine fracture | 4 | 6 |

| 7. | Pelvis fracture | 7 | 10 |

Sn., serial number.

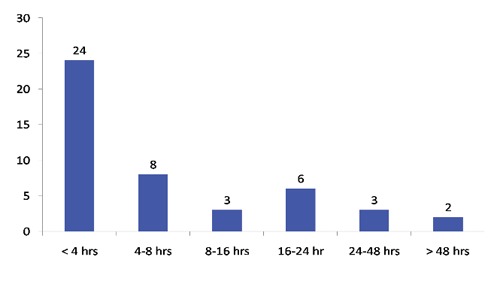

Time of presentation

More than half of the (38) patients presented within 4 h of the incident to us (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time of presentation of patients (hours).

Abdominal injuries

X-ray abdomen, ultrasound abdomen and CT scan abdomen and pelvis were done and multiple injuries were revealed. Splenic injury was observed in 42 (53%) cases, liver trauma in 25 (35%) and small bowel in 12 (17%) cases.

Among genitourinary trauma; renal injuries were commonest in 12 (17%) followed by bladder rupture in 2 cases (Table 3). Retrograde cystogram was done in 2 patients of bladder trauma. Some patients had multiple injuries. Commonest surgery performed was splenectomy in 22 patients followed by perforation closure (Table 4).

Table 3.

Distribution of cases.

| Sn. | Organ involved | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Spleen | 42 | 53 |

| 2. | Liver | 25 | 35 |

| 3. | Small intestine | 12 | 17 |

| 4. | Stomach | 1 | 1 |

| 5. | Mesenteric tear | 8 | 11 |

| 6. | Retroperitoneum hematoma | 14 | 20 |

| 7. | Kidney | 12 | 17 |

| 8. | Bladder | 2 | 3 |

Sn., serial number.

Table 4.

Various procedures performed.

| Sn. | Operative procedures | Number of patients | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Splenectomy | 22 | 30 |

| 2. | Splenorraphy | 3 | 4 |

| 3. | Hepatectomy | 1 | 1 |

| 4. | Resection anastomosis | 3 | 4 |

| 5. | Mesenteric repair | 7 | 10 |

| 6. | Primary bowel repair | 10 | 14 |

| 7. | Gastric rupture repair | 1 | 1 |

| 8. | Nephrectomy | 1 | 1 |

| 9. | Bladder repair | 1 | 1 |

Sn., serial number.

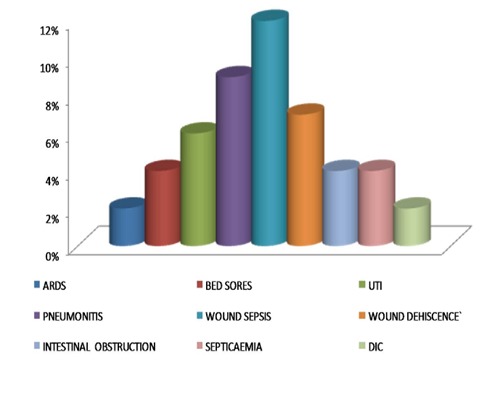

Morbidity and mortality

Mortality rate in our study was seen in 3 (4%) cases in our study out of which 1 was intra-operative. Commonest cause was irreversible shock in 2 (3%) followed by cardiopulmonary arrest 1 (1%). Hepatic injury, splenic laceration and small bowel perforation accounted for the above. Post-operative complications most frequently observed in our study were wound infection in 8 (12%) and wound dehiscence in 5 (7%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Post operative complications. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; UTI, urinary tract infections; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Discussion

Blunt abdominal trauma is an arduous task even to the best of traumatologists. Injuries ranging from single organ to mutilating multi organ trauma may be produced by blunt abdominal trauma. Abdominal findings may be absent in 40% of patients with hemoperitoneum. Sometimes, clinical evaluation of blunt abdominal injuries may be masked by other more obvious external injuries.4 Non therapeutic laparotomies have significantly reduced with proper and timely applications of imaging methods in BAT patients along with physical examination. Unrecognized abdominal injury is a frequent cause of preventable death after trauma.5

The patients who had sustained blunt abdominal trauma may have sustained injury simultaneously to other systems and it is particularly important to examine for injuries of head, thorax and extremities. Vigilance and care of injuries in any of these systems may take precedence over abdominal trauma.

Out of 71 cases in our study 40% of patients were in 21-30 years of age group. This goes in accord with studies of Davis et al.6 and Lowe et al.7 79% cases were males and 21% were females with an M:F ratio of 3.7:1. The male preponderance in our study reflects that the greater mobility of males for either work, such as drivers and mechanics for automobiles or recreational activities may be resulting in a higher exposure to the risk of traffic injuries. Automobile accidents accounted for 53% of cases. This was equivocal with other studies conducted by Perry8 and Morton et al.9 Thus prevention of accidents can decrease fatality.

Commonest intra-abdominal injury was splenic injury in 53% followed by liver injury. Commonest hollow organ injury was small bowel perforation. Most common bowel injured was ileum. These results were consistent with other studies of Davis6 and Morton et al.9

In blunt trauma surgeon’s main concern is control of hemorrhage, but how it can be best done with safety and less morbidity, depends on grade, severity and site of injury. Procedures done for splenic trauma in our study were splenectomy in 22 (30.4%) and splenorraphy in 3 (4%) cases. Splenectomy was done for most of grade 4 and 5 trauma and hemodynamically unstable patients of lesser grades. In 3 cases of grade 3 unstable patients of splenic trauma splenorraphy using prolene mesh was performed. Hemodynamically stable patients were followed with series physical examinations; ultrasonography or CT scans thus avoiding unnecessary laparotomy.

Kidney and urinary bladder injuries were frequently associated with pelvic fractures. Nephrectomy through transperitoneal approach was done in 1 case of extensive renal lacerated Grade 5 injury and the patient recovered uneventfully, otherwise renal injuries were treated conservatively. All patients of renal trauma who were managed conservatively were followed with regular CT scans and all performed well in their course. Most grade I-IV renal injuries can be managed non-operatively. The absolute indications for surgery include renal pedicle injury, shattered kidney, expanding hematoma, and hemodynamic instability. In patients with intraperitoneal urinary bladder injury, laparotomy followed by repair of the bladder was carried out in 2 layers and the patients recovered uneventfully.

Perforation closure was done in 17% cases of bowel injury. Resection and anastomosis was done in 3 cases. Bowel injuries form the major chunk of failure of non-operative management.

One patient of grade V hepatic injury was taken for damage control surgery but the patient was in cardiogenic shock and succumbed to death intra-operatively due to cardiorespiratory arrest in spite of prompt resuscitative measures. The other 2 deaths occurred in postoperative course due to disseminated intravascular coagulation and shock belonged to grade V splenic injury and small bowel trauma.

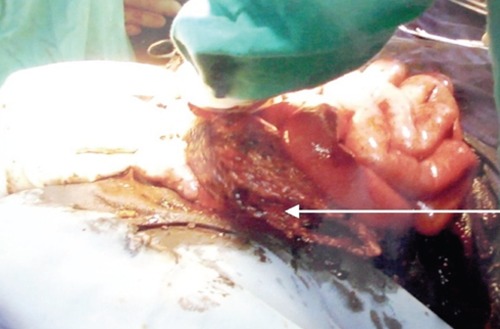

We accounted for 1 rare case of posterior gastric rupture which was closed in 2 layers (Figure 5). The patient had meal 2 h prior and mechanism of injury was assault.

Figure 5.

Posterior gastric rupture with contents.

Surgeon should cautiously look for other sites of trauma to rule out extra-abdominal injuries. Abdominal injuries were associated with various extra-abdominal injuries amongst which most common were rib fractures (20%) and soft tissue injury (20%). Incidence of rib fracture was consistent with study conducted by Fazili10 et al. but we accounted for higher amount of hemothorax and retroperitoneal hematomas. The higher amount of rib fractures were probably due to increase number of upper abdominal trauma. These injuries in any of the systems may take precedence over abdominal trauma. Non-recognition of an extra abdominal injury may contribute to the patients’ death when a relatively simple procedure might otherwise have saved the patient’s life.

Mortality rate in our study was 4% i.e. 3 patients. The major cause of mortality was delayed presentation of patients and poor general condition of patient. This was in contrast to studies conducted by Karamercan,2 Ghulam11 and Alli et al.12 The reason for this was early presentation of patients in our study, early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention. The earliest presentation was at 30 min with one case presenting as late as 15 days after the injury. The early presentation of our patients helped us to start appropriate resuscitation at time and save many lives.

Commonest post operative complication in our study was wound infection (12%) which in most cases were minor infections and were managed conservatively. This was consistent with studies conducted by Beall et al.13 The cause of sepsis/infection in these patients were necrotic tissue, mutilating injuries and late presentation in some patients.

To conclude initial resuscitation measures and correct diagnosis forms the most vital part of blunt abdominal trauma management. Prompt evaluation of abdomen is mandatory to minimize preventable morbidity and mortality. Early diagnosis can decrease mortality by 50%.14 Mortality is related to delayed presentation and diagnosis, associated injuries and delayed surgical intervention. Clinical abdominal assessment is inaccurate of the BAT patients since there are often distracting injuries, altered levels of consciousness, non-specific signs and symptoms, and large differences in individual patient reactions to intra-abdominal injury. Out of multiple modalities available for evaluating stable patients; CT scan along with hemodynamical stability are best in evaluating which patient requires surgery or in deciding which patient can be safely discharged from emergency. The main drawbacks of CT scan are its cost, low sensitivity in detecting bowel injuries and hemodynamically unstable patients. Damage control laparotomy is a potentially life-saving procedure with the potential to mitigate the devastating clinical outcomes.15 Swift recognition, timely and proper application of imaging methods in BAT patients along with physical examination have significantly decreased the number of non-therapeutic and unnecessary laparotomies as a result and has increased NOM of solid organ injuries.

It is the golden hour of injury when prior comprehensive action can save lives. Stitch in time saves nine.

Table 1.

Causes of trauma.

| Sn. | Causes of blunt trauma | Number of patients | Percentage of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Motor vehicle accident | 38 | 53 |

| 2. | Fall from height | 30 | 43 |

| 3. | Assault | 3 | 4 |

Sn., serial number.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Department of General Surgery and Head of the Department Surgery for providing support in preparing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

Funding: funds were provided by Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangalore, India.

References

- 1.van der Vlies CH, Olthof DC, Gaakeer M. Changing patterns in diagnostic strategies and the treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs. Int J Emerg Med 2011;4:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmet K, Tongue Y. Blunt abdominal trauma: evaluation of diagnostic options and surgical outcomes. Turkish J Trauma Emerg Surg 2008;14:205-10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandes T Marconi, Escocia Dorigatti A, Monteiro BT. Nonoperative management of splenic injury grade IV is safe using rigid protocol. Rev Col Bras Cir 2013;40: 323-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan R, Aziz AA. Computerized tomography (CT) imaging of injuries of blunt abdominal trauma: a pictorial assay. Malays J Med Sci 2010;17:29-39 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taviloglu K, Yanar H. Current trends in the management of blunt solid organ injuries. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2009;35:90-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis J, Cohn I, Nance F. Diagnosis and management of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Surg 1996;183:880-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe RJ, Boyd DR, Frank CM, Baker RJ. The negative laparotomy for abdominal trauma. J Trauma 1997; 2:853-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry JF, Jr, McCleelan RJ. Autopsy findings in 127 patients following fatal traffic accidents. Surg Gynaec Obstet 1964;119: 586-90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton J, Hinshaw R. Blunt trauma to the abdomen. Ann Surg 1957;145:699-711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazili A, Nazir S. Clinical profile and operative management of blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective one year experience at SMHS hospital, Kashmir, India. JK Practit 2001;8:219-21 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diercks DB, Mehrotra A, Nazarian DJ. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 2011;4:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alli N. Management of blunt abdominal trauma in Maiduguri: a retrospective study. Niger J Med 2005;14:17-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beall AC, Bricker DL, Alessi FJ, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of civilian colon injuries. Ann Surg 1970;173:971-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majid S, Gholamreza F, Mahmoud YM. New scoring system for intraabdominal injury diagnosis after blunt trauma. Chin J Traumatol 2014;17:19-24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S-Y, Liao C-H, Fu C-Y, Kang S-C. An outcome prediction model for exsanguinating patients with blunt abdominal trauma after damage control laparotomy: a retrospective study. BMC Surg 2014;14:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]