Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is an extremely prevalent but poorly understood gastrointestinal disorder. Consequently, there are no clear diagnostic markers to help diagnose the disorder and treatment options are limited to management of the symptoms. The concept of a dysregulated gut-brain axis has been adopted as a suitable model for the disorder. The gut microbiome may play an important role in the onset and exacerbation of symptoms in the disorder and has been extensively studied in this context. Although a causal role cannot yet be inferred from the clinical studies which have attempted to characterise the gut microbiota in IBS, they do confirm alterations in both community stability and diversity. Moreover, it has been reliably demonstrated that manipulation of the microbiota can influence the key symptoms, including abdominal pain and bowel habit, and other prominent features of IBS. A variety of strategies have been taken to study these interactions, including probiotics, antibiotics, faecal transplantations and the use of germ-free animals. There are clear mechanisms through which the microbiota can produce these effects, both humoral and neural. Taken together, these findings firmly establish the microbiota as a critical node in the gut-brain axis and one which is amenable to therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Microbiome, Anxiety, Tryptophan, Abdominal pain, Gastrointestinal motility, Cognition

Core tip: A dysregulated gut-brain axis may be responsible for the main features of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). However, the role of the gut microbiota is an underappreciated but critical node in this construct. Numerous clinical studies have documented various alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota in IBS, indicating defects in stability and diversity of this virtual organ. Manipulation of the gut microbiome influences the symptom profile in IBS and clear mechanisms have been elucidated to explain these interactions. This has important clinical implications and may offer hope for future treatment options to alleviate the suffering caused by this debilitating disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder accounting for up to 50% of visits to general practitioners for GI complaints[1]. Despite considerable research efforts, adequate treatment of GI symptoms in IBS has proved a considerable challenge and remains a venture undermined by a poorly understood pathophysiology[2]. That such a rudimentary grasp of this debilitating condition persists despite a high worldwide community prevalence, between 10%-25% in developed countries, offers some perspective on the complex character of the disorder[3-5]. Impairments in the quality of life of afflicted individuals are associated with a chronic symptom profile incorporating abdominal pain, bloating and abnormal defecation[6]. Patients with IBS were painfully aware of the kind of signals the gut can send to the brain long before the concept of a dysregulated gut-brain axis emerged as the favoured explanation for their travails[7]. This bidirectional communication system provided the basis for incremental and much needed improvements in our understanding of IBS[8]. In parallel, it has become increasingly apparent that the gut microbiome constitutes a critical node within this axis in both health and disease[9-11].

In this review, we briefly detail the key components of the microbiota-gut-brain axis and critically evaluate the evidence, both direct and indirect, supporting a role for microbiome perturbations in IBS. The ability of this virtual organ to influence the gut-brain axis and relevant behaviours is explored and putative mechanisms outlined. Finally, we discuss the diagnostic and therapeutic implications arising from this corpus of knowledge.

MICROBIOME-GUT-BRAIN AXIS

The microbiome-gut-brain axis comprises a number of fundamental elements including the central nervous system (CNS), the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems, both the sympathetic and parasympathetic limbs of the autonomic nervous system, the enteric nervous system (ENS) and, of course, the gut microbiome[9,12]. Signalling along the axis is facilitated by a complex reflex network of afferent fibers projecting to integrative cortical CNS structures and efferent projections to the smooth muscle in the intestinal wall[13]. Thus, a triad of neural, hormonal and immunological lines of communication combine to allow the brain to influence the motor, sensory, autonomic and secretory functions of the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 1). These same connections allow the gastrointestinal tract to modulate brain function[7,10]. Although reciprocal communication between the ENS and the CNS is well described, the proposed role of the gut microbiota within this construct remains to be fully defined. The commitment to building a more complete picture of our legion of gastrointestinal inhabitants in both health and disease and their myriad of functions is clear from large-scale projects such as the NIH funded Human Microbiome Project[3]. Thus, it is becoming increasingly certain that our gut microbiome has a hand in virtually all aspects of normal physiological processes including those immunological features which buttress the gut-brain axis[14,15]. Interestingly, in the context of IBS as a stress-related disorder, the composition of the gut microbiota can be influenced by stressors[16,17] and the gut microbiome can itself regulate the host endocrine repertoire[18,19].

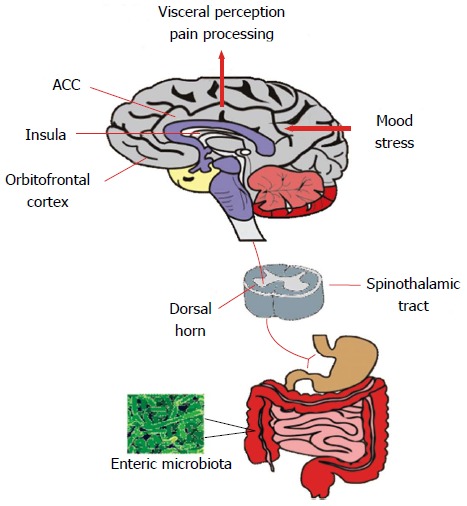

Figure 1.

Microbiome-gut-brain Axis. The central nervous system (CNS) and enteric nervous system (ENS) communicate along vagal and autonomic pathways to modulate many gastrointestinal (GI) functions. The enteric microbiota influence the development and function of the ENS and immune system which affects CNS function. The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis forms a key component of brain-gut signalling, responding to stress or heightened immune activity. Mood and various cognitive processes can mediate top-down bottom / bottom-up signalling. The HPA axis can be activated in response to environmental stress or by elevated systemic proinflammatory cytokines. Cortisol released from the adrenal glands feeds back to the pituitary, hypothalamus (HYP), amygdala (AMG), hippocampus (HIPP) and prefrontal cortex (PFC) to shut off the HPA axis. Cortisol released from the adrenals has a predominantly anti-inflammatory role on the systemic and GI immune system. In response to stress, GI activity can be altered and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) increased. Stress can increase systemic proinflammatory cytokines which can act at the pituitary to activate the HPA axis and can signal to the central nervous system via the vagus nerve, which also transmits changes due to mast cell activation in the GI tract.

IBS AND MICROBIOME: DIRECT EVIDENCE

The true nature of gut microbiota disturbances in IBS and the functional consequences remains elusive and although direct evidence for alterations does exist, it is perhaps not as conclusive or consistent as one might expect for consideration as a prototypical microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder (Table 1). Much of the evidence predates the metagenomic approaches which now dominate this terrain and these early studies indicated subtle qualitative and quantitative alterations as well as a temporal instability in the composition of the microbiota in IBS compared to healthy controls[20-24]. Since a stable but diverse microbiota is generally considered beneficial to health, these studies provided a plausible basis to further consider shifts in microbiota composition as a pathogenic factor in IBS.

Table 1.

Microbiota alterations in irritable bowel syndrome

| Sample type/method | Subjects recruited | Key finding | Ref. |

| Faecal microbiota (at 3 mo intervals)/Q-PCR (covering about 300 bacterial species) | IBS (27, Rome II Criteria; IBS-D = 12; IBS-C = 9; IBS-A = 6); Healthy Controls (22) | Decreased Lactobacillus spp in IBS-D; Increased Veillonella spp in IBS-C; Differences in the Clostridium coccoides subgroup and Bifidobacterium catenulatum group between IBS patients and controls | [22] |

| Faecal microbiota/Q-PCR (10 bacterial groups), Culture, HPLC | IBS (26, Rome II/III; IBS-D = 8; IBS-C = 11, IBS-A = 7); Healthy Controls (26) | Higher counts of Veillonella and Lactobacillus in IBS vs controls; Higher levels of acetic acid, propionic acid and total organic acids in IBS vs controls | [52] |

| Faecal microbiota(0, 3, 6 mo)/Culture-based techniques, PCR-DGGE analysis | IBS (26, Rome II; IBS-D = 12; IBS-C = 9; IBS-A = 5); Healthy Controls (25) | More temporal instability in IBS group; No difference in the bacteroides, bifidobacteria, spore-forming bacteria, lactobacilli, enterococci or yeasts, Slightly higher numbers of coliforms as well as an increased aerobe:anaerobe ratio in IBS group | [23] |

| Faecal microbiota/DNA-based PCR-DGGE, RNA-based RT-PCR-DGGE | IBS (16, Rome II; IBS-D = 7; IBS-C = 6; IBS-A = 3); Healthy Controls (16) | Higher instability of the bacterial population in IBS compared to controls; Decreased proportion of C. coccoides-Eubacterium rectale in IBS-C | [24] |

| Faecal Microbiota/GC Fractionation, 16S ribosomal RNA gene cloning and clone sequencing, qRT-PCR | IBS (24, Rome II; IBS-D = 10; IBS-C = 8; IBS-A = 6); Healthy Controls (23) | Significant differences in phylotypes belonging to the genera Coprococcus, Collinsella and Coprobacillus | [20] |

| Faecal Microbiota/GC Fractionation, 16S ribosomal RNA gene cloning and clone sequencing, qRT-PCR | IBS (12, Rome II, All IBS-D); Healthy Controls (22) | Significant differences between clone libraries of IBS-D patients and controls; Microbial communities of IBS-D patients enriched in Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, reduced Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes compared to control; Greater abundance of the family Lachnospiraceae in IBS-D | [26] |

| Faecal Microbiota/qRT-PCR | IBS (20, Rome II; IBS-D = 8; IBS-C = 8; IBS-M = 4); Healthy Controls (15) | Intestinal microbiota of the IBS-D patients differed from other sample groups; A phylotype with 85% similarity to C. thermosuccinogenes significantly different between IBS-D and controls/IBS-M; A phylotype with 94% similarity to R. torques more prevalent in IBS-D than controls; A phylotype with 93% similarity to R. torques was altered in IBS-M compared to controls; R. bromii-like phylotype altered in IBS-C comparison to controls | [244] |

| Faecal Microbiota/DGGE 16s rRNA | IBS (11, Rome II); Healthy Controls (22) | Biodiversity of the bacterial species was significantly lower in IBS than controls; presence of B. vulgatus, B. ovatus, B. uniformis and Parabacteroides sp. in healthy volunteers distinguished them from IBS | [31] |

| Faecal Microbiota/DGGE 16s rRNA, qRT-PCR, GC-MS | IBS (11, Rome II; Non-IBS patients (8) | IBS subjects had a significantly higher diversity Bacteroidetes and Lactobacillus groups; Less diversity for Bifidobacteria and C. coccoides; Elevated levels of amino acids and phenolic compounds in IBS which correlated with the abundance of Lactobacilli and Clostridium | [51] |

| Faecal Microbiota and sigmoid colon biopsies/DGGE 16s rRNA | IBS (47, Rome II); Healthy Controls (33) | Significant difference in mean similarity index between IBS and healthy controls; Significantly more variation in the gut microbiota of healthy volunteers than that of IBS patients | [29] |

| Faecal Microbiota and brush duodenal samples/FISH + qRT-PCR | IBS (41, Rome II; IBS-D = 14, IBS-C = 11; IBS-A = 16); Healthy Controls (26) | 2-fold decrease in the level of bifidobacteria in IBS patients compared to healthy subjects; no major differences in other bacterial groups. At the species level, B. catenulatum significantly lower in IBS patients in both faecal and duodenal brush samples than in healthy subjects | [21] |

| Faecal Microbiota and brush duodenal samples/DGGE 16s rRNA, q-RT-PCR | IBS (37, Rome II; IBS-D = 13, IBS-C = 11; IBS-A = 13); Healthy Controls (20) | Higher levels P. aeruginosa in the small intestine and faeces of IBS than healthy subjects | [47] |

| Faecal Microbiota and colonic mucosal samples/Culture, qRT-PCR | IBS (10, Rome III, all IBS-D); Healthy Controls (10) | Significant reduction in the concentration of aerobic bacteria in faecal samples from D-IBS patients when compared to healthy controls 3.6 fold increase in concentrations of faecal Lactobacillus species between D-IBS and healthy controls; No significant differences were observed in the levels of aerobic or anaerobic bacteria in colonic mucosal samples between D-IBS patients healthy controls; No significant differences in mucosal samples between groups for Clostridium, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species and E. coli | [46] |

| Faecal Microbiota and colonic mucosal samples/T-RFLP) fingerprinting of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene | IBS (16, Rome III, All IBS-D); Healthy Controls (21) | 1.2-fold lower biodiversity of microbes within faecal samples from D-IBS compared to healthy controls; No difference in biodiversity of mucosal samples between D-IBS and healthy controls | [30] |

| Faecal Microbiota/Phylogenetic microarray, qRT-PCR | IBS (62, Rome II; IBS-D = 25; IBS-C = 18; IBS-A = 19); Healthy Controls (46) | 2-fold increased ratio of the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in IBS; 1.5-fold increase in numbers of Dorea, Ruminococcus and Clostridium spp; 2-fold decrease in the number of Bacteroidetes; 1.5-fold decrease in Bifidobacterium and Faecalibacterium spp; 4-fold lower average number of methanogens | [28] |

| Rectal biopsies/FISH | IBS (47, Rome III; IBS-D = 27, IBS-C = 20); Healthy Controls (26) | Greater numbers of total mucosa-associated bacteria per mm of rectal epithelium in IBS than controls, comprised of bacteroides and Eubacterium rectale-C. coccoides; Bifidobacteria lower in the IBS-D group than in the IBS-C group and controls; Maximum number of stools per day negatively correlated with the number of mucosa-associated Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli only in IBS | [33] |

| Faecal Microbiota/16s rRNA amplicon pyrosequencing | IBS (37, Rome II; IBS-D = 15, IBS-C = 10, IBS-A = 12); Healthy Controls (20) | IBS subgroup (n = 22) defined by large microbiota-wide changes with an increase of Firmicutes-associated taxa and a depletion of Bacteroidetes-related taxa | [27] |

| Faecal Microbiota/Phylogenetic microarray, qRT-PCR | IBS (23, Rome II; IBS-D = 12, PI-IBS = 11); 11 Healthy Controls (11); Subjects who 6 mo after gastroenteritis experienced no bowel dysfunction (PI-nonBD, n = 12) or had recurrent bowel dysfunction (PI-BD, n = 11) | Bacterial profile of 27 genus-like groups separated patient groups and controls; Faecal microbiota of patients with PI-IBS differs from that of healthy controls and resembles that of patients with IBS-D; Members of Bacteroidetes phylum were increased 12-fold in patients, while healthy controls had 35-fold more uncultured Clostridia; Correlation between index of microbial dysbiosis and amino acid synthesis, cell junction integrity and inflammatory response | [50] |

| Faecal Microbiota/Phylogenetic Microbiota Array, high-throughput DNA sequencing, r-RT- PCR, FISH | IBS (22, pediatric Rome III, All IBS-D); Healthy Controls (22) | At the higher taxonomical level gut microbiota was similar between healthy and IBS-D children. Levels of Veillonella, Prevotella, Lactobacillus and Parasporo bacterium increased in IBS, Bifidobacterium and Verrucomicrobium less abundant in IBS | [35] |

| Faecal Microbiota/16s rRNA pyrosequencing, DNA microarray (Phylochip) | IBS (22, Pediatric Rome III; IBS-D = 1, IBS-C = 13; IBS-U = 7, other = 1); Healthy Controls (22) | Greater percentage of the class gamma-proteobacteria in IBS compared to controls; Novel Ruminococcus-like microbe associated with IBS; Greater frequency of pain in IBS correlated with an increased abundance of several bacterial taxa from the genus Alistipes | [34] |

IBS (D/C/A/U): Irritable bowel syndrome (diarrhoea/constipation/alternating/unsub typed); PI: Post-infectious; Q: Quantitative; DGGE: Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis; qRT: Quantitative reverse transcriptase; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; HPLC: High performance liquid chromatography; GC: Gas chromatograph; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid; RNA: Ribonucleic acid; rRNA: Ribosomal ribonucleic acid; FISH: Fluorescence in situ hybridization; T-RFLP: Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Although no consensus has emerged regarding the precise differences which are present, the application of modern high-throughput culture-independent techniques of superior resolution has largely supported the general thrust of the earlier findings[25]. At the phylum level, one of the more consistent findings across techniques appears to be the enrichment of Firmicutes and a reduced abundance of Bacteroidetes[26-28]. Such alterations may contribute to the reported lower diversity in the gut microbiota of IBS subjects compared to healthy controls[29-31]. More work remains to determine whether the Rome III defined subtypes of IBS[32] are reflected in distinct microbiota conformations but it has been reported that there is a lower abundance of mucosa-associated Bifidobacteria in diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D) compared to constipation predominant IBS (IBS-C) patients[33]. There are also reports of subtype specific faecal microbiome compositions in children with IBS[34]. Interestingly, it has also been reported that children diagnosed with IBS-D also have a lower abundance of some members of the Bifidobacterium genera compared to healthy controls[35]. This suggests that alterations in the gut microbiota occur early in life and could be a chronic feature of IBS across the lifespan but this possibility requires further investigation and verification. The application of pyrosequencing technology to faecal samples has yielded a number of interesting findings including cohorts within the overall IBS group with both an altered and similar microbiota compared to healthy controls suggesting that microbiota differences might only be a feature in a subset of IBS patients[27]. Of further note in this study was the presence of distinct microbiota defined subtypes of IBS among those cohorts with an altered microbiota which were unrelated to the Rome III defined categories.

Differential microbiota compositions might not necessarily have functional consequences but there are some indications that the reported alterations have relevance for symptom expression in IBS. Of note is the report in healthy adults that subjects who experienced pain, assessed by questionnaire, over the 7 wk duration of the study had over five-fold less Bifidobacteria compared to those without pain[36]. However, in general, the association between specific symptoms and microbiota alterations remains under-investigated in IBS. Studies which have examined this topic have reported associations between stool frequency and musoca-associated Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli[33], a correlation between Firmicutes and Proteobacteria and symptom scores[28] as well as a correlation between symptom scores and a Ruminococcus-torques-like phylotype[37].

Although the findings discussed above affirm the likelihood of a perturbed microbiome in IBS, some caution is advisable and a number of caveats should be considered before reaching this conclusion. All studies, not just those concerned with characterising the microbiota, must contend with the considerable heterogeneity within this patient group. There is no doubt that this lack of uniformity contributes to some of the inconsistencies in the reported data and larger studies are required which factor in not just IBS subtypes but also the influence of gender, genetics, presence of comorbidities, whether the patients recruited are in the active or quiescent phase at the time of sampling and increased standardisation in healthy control cohorts[38]. This feature is then superimposed on our rapidly evolving impressions of what constitutes a healthy microbiome which is highly individual specific but still lacks full definition[39-41]. Diet plays a major role in shaping the gut microbiota[42-44] and given the often self-imposed dietary restriction practises among the IBS population[45], it is difficult to rule out the possibility that the observed alterations are a consequence of these changes. Indeed, in isolation, the studies outlined do not clearly establish a causal role for the microbiome in IBS and the alterations described could be a consequence not just of dietary alterations but also the main GI symptoms, which wax and wane, as well as the altered stress reactivity.

Considerable debate also exists surrounding the sample type used across the various studies. Practical logistical reasons favour faecal sampling protocols but this strategy fails to capture the complexity of the gut microbiota and the clear distinction between the mucosa-associated and lumen residing microbiota. There is also a microbiota gradient along the gastrointestinal tract which is not captured by a faecal microbiota analysis. Although some studies have logically attempted to link alterations in the faecal microbiota with disturbances in the musosa-associated microbial complement[21,29,30,33,46,47], the precise relationship between altered composition, diversity and/or stability in the faecal compartment and microbe-mucosa interactions remains to be fully defined. Indeed, the subtleties of any equilibrium between these different microbial niches is the subject of on-going investigation in both and health and disease and we cannot yet confidently predict how one affects the other, either positively or negatively. Other methodological considerations relating to the merits and limitations of the variety of techniques which have been used to characterise the microbiome in IBS are likely to have contributed to some of the inconsistencies reported[48,49]. The consequences of any altered composition are less frequently reported although a number of interesting studies have taken this approach[50-52] which is likely to feature more prominently as the field undertakes to establish not just who is or isn’t there but also what they are or are not doing.

IBS AND MICROBIOME: INDIRECT EVIDENCE

The lack of consensus in studies which have sought to directly quantify microbiota alterations in IBS has prompted the consideration of alternative but more indirect lines of support. These approaches are in line with the recognised requirement for a better knowledge of the mechanisms through which changes in microbiota composition can promote disease to help the transition for correlation to causation[53,54].

An endorsement of the importance of the gut microbiome is taken from the emergence of IBS following an enteric infection, post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), which bears most similarity to IBS-D[55]. One of the highest incidences of this phenomenon, 36%, was reported following a gastroenteritis outbreak in Walkerton due to contamination of the town water supply[56]. The ability of certain probiotic strains to ameliorate some symptoms of IBS also indicts dysbiosis of the microbiota as an important factor in the disorder[57]. Interestingly, antibiotic usage has been linked with both an increased risk for IBS[58,59] as well having some beneficial effects as in the case of rifaximin[60,61]. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) has also been proposed as a factor in IBS and while it can be responsible for IBS-like symptoms, it remains a controversial topic and inadequately substantiated[62]. The presence of low grade inflammation could potentially be driven by an altered microbiota composition and in turn support a proinflammatory microbial community and offers a further strand of support[8,25,63]. Taken together, this direct and indirect evidence makes a plausible case to include the microbiome as a critical conceptual node in a framework for understanding the disorder.

IBS SYMPTOMS AND MICROBIOTA

If gut microbiome disturbances are pertinent to IBS, then this virtual organ should demonstrate an ability to influence the canonical symptoms of the disorder as well as other prominent behavioural alterations. In addition, it should be possible to therapeutically target the microbiome to ameliorate the symptoms which are purported to be under its influence. This certainly seems to be the case for the abdominal pain component of the disorder which is underpinned by visceral hypersensitivity (Figure 2) in a large proportion of individuals with IBS[64-66]. It appears, for example, that the visceral hypersensitivity phenotype characteristic of IBS can be transferred via the microbiota of IBS patients to previously germ-free rats[67]. In other preclinical approaches, visceral hypersensitivity is also induced following manipulation of the intestinal microbiome with antibiotics[68] and following deliberate infection[69,70] or endotoxin administration[71]. Moreover, maternal separation, an early-life stress based animal model of IBS, produces an adult phenotype with both an altered microbiota and visceral hypersensitivity[13,17].

Figure 2.

Visceral pain perception. The microbiota can influence the spinothalamic projections from the gastrointestinal tract which reach higher cortical areas including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex where visceral sensory and pain signals reach the conscious awareness. These regions mediate the cognitive processing of visceral signals and integrate mood and stress-related information and initiate autonomic and behavioural responses. ACC: Anterior cingulate cortex.

From a therapeutic perspective, certain probiotic strains, such as B. infantis 35624 and Lactobacillus acidophilus, can ameliorate colonic hypersensitivity in animal models[72-74] and this and other probiotic strains are also of some benefit in clinical populations[57,75]. Interestingly, visceral hypersensitivity due to chronic psychological stress in mice can be prevented by pre-treatment with oral rifaximin[76]. Also of note is that mast cells have been implicated as a downstream mediator of microbiota-driven immune alterations in the pain component of IBS[77-80] and a mast cell stabiliser, disodium cromoglycate, can reverse colonic visceral hypersensitivity in a stress-sensitive rat strain used to model IBS[81].

Although not simply a bowel habit disorder of disrupted gastrointestinal motility and transit[82], it does appear likely that these features might at least partially explain the altered defecatory patterns that are typical of IBS[83]. Clearly, it has long been known that both enteric infections and antibiotics can induce diarrhoea[84,85]. Certain strains of probiotic have demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of diarrhoea[86]. Thus, a role for the microbiota in the regulation of colonic motility has been proposed[87] and the interaction between the intestinal microbiota and the gastrointestinal tract also regulates absorption, secretion and intestinal permeability[88]. The olfactory bulbectomy mouse model of depression has recently been shown to have both an altered microbiota and aberrant colonic motility[89]. However, the effect of the gut microbiota on gastrointestinal transit is complex and studies in humanized mice indicate that while GI transit can be regulated by the microbiota, this is a diet-dependent feature[90]. Of course, gut motor patterns can also influence the microbiota, highlighting further the bidirectional, intricate nature of the relationship[91]. Studies in mice indicate a role for gut microbial products in the regulation of gastrointestinal motility via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)[92]. Given the recent association between this receptor and the control of stress-induced visceral pain in mice[93], it may represent an interesting target for modulation of two cardinal features of IBS.

Psychiatric comorbidity in IBS

It is well established that psychiatric comorbidities, particularly anxiety and depression, are common among patients with IBS[94,95]. Although concerns about the screening instruments such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) used in research studies are noted[96-98], psychiatric co-morbidity is readily identifiable in IBS when well validated instruments such as the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR are employed[99]. Following acute gastroenteritis, prior anxiety and depression has been identified as a risk factor for the subsequent development of PI-IBS[100,101]. Higher anxiety and depression scores have also been reported in this population following the initial infection[102]. Prenatal infection can also result in a depressive phenotype in adult mice[103]. Following endotoxin challenge in rodents, depressive-like behaviours can emerge once the initial inflammation-induced sickness behaviours subside[104]. This complexity indicates that a reciprocal relationship is likely, an important consideration when discussing the association between changes in the gut microbiota in IBS and central disturbances. Such alterations may then be secondary to changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, or indeed, perturbations of the gut microbiota, via pathways of the brain-gut axis, may arise as a result of changes in central function.

While as yet neither correlative or causative clinical studies exist that directly interrogate the qualitative and quantitative structure of the gut microbiome in psychiatric illnesses for abnormalities, there is now strong evidence from the preclinical literature that changes in the microbiome can influence these aspects of brain and behaviour[12,14]. This is most convincing for anxiety-like behaviours and multiple independent teams of researchers have confirmed in proof of principle studies that germ-free mice are less anxious than their conventionally colonised counterparts[105-107] while reintroduction of the microbiota prior to critical time windows can normalise these behaviours[105]. Ablation of the microbiota in mice using a non-absorbable antimicrobial cocktail reproduces this behavioural feature while it has also been established that this is a trait which is transmissible via the microbiota[108]. Interesting, in germ-free rats, absence of the microbiota seems to confer elevated levels of anxiety-like behaviours[109] but regardless of the direction of the alterations, these studies confirm that this is a behaviour under the influence of the microbiota. Deliberate infection of the GI tract in mice also consistently produces an anxious phenotype[110-112] while certain probiotic strains may have anxiolytic potential[113].

Although there are now a number of examples of animal models of depression which have an altered microbiota[17,89,114], the preclinical evidence linking the microbiota to depressive-like behaviours is mostly derived from probiotic studies where certain strains such as L. rhamnosus[115], B. infantis[116] and a formulation of L. helveticus and B. longum displayed antidepressant like properties[117]. Interestingly, the latter study also demonstrated that at least in healthy volunteers, targeting the microbiota in this manner could alleviate psychological distress including an index of depression.

Evidence from the clinical domain comes indirectly from the utility of a variety of antibacterial agents in the modulation of depression. This includes, in addition to support from preclinical studies[118,119], preliminary clinical confirmation that minocycline (a broad-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic) possesses antidepressant properties[120,121]. Whether this effect generalises to all tetracycline antibiotics is not known but another member of this class, doxycycline, seems to have similar beneficial effects, at least in preclinical studies[122]. The mechanism of action of minocycline has been considered in the context of neuroprotection, suppression of microglial activation or anti-inflammatory actions and it does reach clinically relevant concentrations in the CNS[123]. Even if its anti-inflammatory action is distinct from its antimicrobial action as when used in preclinical stroke models[124], the action of minocycline against bacteria in the gut now need to be considered in its putative antidepressant effects. Indeed, a number of other antimicrobial agents have shown some potential as antidepressants but all have other relevant mechanisms of action which have been preferentially adopted to explain their efficacy. This includes D-cycloserine[125] [antibiotic effective against tuberculosis which is also a partial agonist of the N-methyl-D-asparate (NMDA) receptor] and ceftriaxone[126] (a beta-lactam antibiotic that also stimulates uptake of glutamate). Moreover, in aged populations fluoroquinolone antibiotics can potentially induced depressive symptoms[127]. Similarly, norfloxacin (a quinoline antibiotic with antibacterial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria) has been linked with depressive side effects in the clinic[128]. It is also interesting to note that iproniazid, a drug which in many ways sparked the monoamine hypothesis of depression and heralded the psychopharmacological era in the management of depression, is primarily an antimicrobial agent whose antidepressant effects were presumed to be mediated via inhibition of monoamine oxidase[129]. It would not be without irony if future treatment options for depression, as has been suggested, focus instead on targeting the microbiota[114,130].

Cognition function in IBS

Extensive cognitive testing in germ-free animals has not been carried out, likely as it is logistically challenging and the difficulty in conducting the lengthy testing protocols required while simultaneously maintaining the animal in a germ-free state should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, studies which have used the most feasible paradigms such as novel object recognition and the T-maze have demonstrated non-spatial, hippocampal mediated, and working memory deficits[131]. In addition, germ-free animals also exhibit pronounced social-cognitive deficits relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders which can be partially ameliorated by bacterial colonisation of the gut[132]. Studies in conventional mice have shown that infection with C. rodentium combined with acute stress, leads to memory dysfunction which could be prevented by daily administration of a probiotic prior to infection[131], thus highlighting a complex interaction between stress and the gut microbiota on brain function. In addition, modulating the composition of the gut microbiota using a specific diet has been shown to affect cognition in conventional mice[133,134].

Clinically, the influence of microbial disturbances on cognitive performance has long been recognised in hepatic encephalopathy where cognitive impairment, which in some cases may present as dementia, can be reversed with oral antibiotic treatment[135,136]. Although data linking changes in the gut microbiota with cognitive function in IBS is currently lacking, there is nevertheless a growing body of evidence that cognitive alterations may be a key feature of IBS and other brain-gut axis disorders[7,137]. Initial studies focusing on cognitive function within the cognitive-behavioural model of IBS[138,139] identified that patients exhibit greater attention to GI symptom and pain related stimuli (Table 2 for details). This enhanced attention to, and inability to re-direct attention from, GI symptoms, purportedly maintains a continual cycle of symptom exacerbation which can be ameliorated in some patients using cognitive-behavioural psychotherapeutic techniques (for extensive review of the cognitive-behavioural model of IBS[137]).

Table 2.

Cognitive performance in irritable bowel syndrome

| Cognitive domain | Sample size: IBS/Control/Other | IBS subtype | Sex Male:Female | Mean age IBS/Control/Other | Key finding | Ref. |

| Visuospatial memory | 39/40 | IBS-D = 7; IBS-C = 4; IBS-A = 28 | 6:33 (IBS) | 28/28 | Impaired performance which correlated with salivary cortisol levels | [140] |

| 11:29 (Control) | ||||||

| 40/41 | N.S. | 13:27 (IBS) | 37/43 | No group differences | [245] | |

| 16:25 (Control) | ||||||

| Working memory | 39/40 | IBS-D = 7; IBS-C = 4; IBS-A = 28 | 6:33 (IBS) | 28/28 | No group differences | [140] |

| 11:29 (Control) | ||||||

| 40/41 | N.S. | 13:27 (IBS) | 37/43 | No group differences | [245] | |

| 16:25 (Control) | ||||||

| Cognitive flexibility | 30/30 | IBS-D = 13; IBS-C = 13; IBS-A = 4 | 15:15 (IBS) | 21/21 | Impaired cognitive flexibility and altered frontal brain activity in IBS | [141] |

| 15:15 (Control) | ||||||

| 39/40 | IBS-D = 7; IBS-C = 4; IBS-A = 28 | 6:33 (IBS) | 28/28 | No group differences | [140] | |

| 11:29 (Control) | ||||||

| 40/41 | N.S. | 13:27 (IBS) | 37/43 | No group differences | [245] | |

| 16:25 (Control) | ||||||

| Selective attention | 39/40 | IBS-D = 7; IBS-C = 4; IBS-A = 28 | 6:33 (IBS) | 28/28 | No group differences | [140] |

| 11:29 (Control) | ||||||

| 40/41 | N.S. | 13:27 (IBS) | 37/43 | No group differences | [245] | |

| 16:25 (Control) | ||||||

| 27/27 | N.S. | 3:24 (IBS) | 45/42 | No group differences | [246] | |

| 3:24 (Control) | ||||||

| Reaction time | 40/41 | N.S. | 13:27 (IBS) | 37/43 | No group differences | [245] |

| 16:25 (Control) | ||||||

| Affective attention | 15/15 | IBS-D = 6; IBS-C = 3; IBS-A = 3; Other = 3 | 4:11 (IBS) | 30/30 | Enhanced attention to GI symptom-related words | [247] |

| 5:10 (IBS) | ||||||

| 20 (Rome II Criteria)/33 | N.S. | 2:18 (IBS) | 31/27 | Enhanced attention to pain-related words | [248] | |

| 12:21 (Control) | ||||||

| 36 (Rome II Criteria)/40 (mixed organic GI disease) | N.S. | 12:24 (IBS) | 35/36 | Enhanced recognition of GI-related words | [249] | |

| 16:24 (mixed organic GI disease) | ||||||

| Affective memory | 30 (Manning criteria)/30/28 (depressed patients)/28 (organic GI disease) | N.S. | N.S. | 36/35/38/27 (median age) | Enhanced recall of negative words compared to control and organic GI disease - no difference in comparison to depression group | [250] |

GI: Gastrointestinal; IBS (D/C/A): Irritable bowel syndrome (diarrhoea/constipation/alternating); N.S.; Not specified.

An advanced understanding of cognitive alterations in IBS has been provided by recent studies utilising well validated and sensitive neuropsychological measures with patients. For example, patients with IBS have been found to exhibit a hippocampal mediated visuospatial memory deficit which was related to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity[140]. In addition, a study employing functional brain imaging reported that patients were impaired on a test of cognitive flexibility, whilst also displaying abnormal brain activity in frontal brain regions during the task[141]. However, there is a disparity in findings between studies (Table 2) which likely reflects the noted heterogeneity of IBS and different approaches to subject matching on the basis of demographic and other important variables. Regardless of these methodological drawbacks, such studies have added to our understanding of the complex behavioural phenotype of IBS. When considering the gut microbiota mediated alterations in brain function and cognition that have been shown pre-clinically[115,131,132,134], it is likely that an altered gut microbiota may leverage a significant influence on cognitive dysfunction in IBS. Of note then, is a recent study in a healthy human population which has provided preliminary evidence that intake of a fermented milk product with probiotic can modulate brain activity in regions involved in mediating cognitive performance[142]. As such, interventions targeting the gut microbiota in IBS may prove beneficial in alleviating impaired cognition and associated central alterations.

STRESS, IBS AND THE GUT MICROBIOTA

Stress impacts greatly on virtually all aspects of gut physiology relevant to IBS including motility, visceral perception, gastrointestinal secretion and intestinal permeability while also having negative effects on the intestinal microbiota[17,143,144]. A maladaptive stress response may thus be fundamental to the initiation, persistence and severity of symptoms in IBS as well as the stress-related psychiatric comorbidities[145]. Although the findings pertaining to HPA axis irregularities in IBS are far from consistent[8,137], the well validated Trier Social Stress Test (TSST)[146] has recently been used to demonstrate a sustained HPA axis response to an acute stress in IBS, possibly indicating an inability to appropriately shutdown the stress response[147].

Accumulating evidence suggests aberrant stress responses could be mediated via the gut microbiota. A landmark study by Sudo et al[148] neatly validated this possibility by demonstrating the absence of a gut microbiota impaired control of the stress response, at least in terms of the exaggerated corticosterone production following acute stress in germ-free mice[148]. Subsequently independently replicated[105], the ability of the microbiota to modulate the stress response is also evident following probiotic administration[115], C. rodentium infection[131] and indeed following colonisation of germ-free mice[148]. Many now view the gut microbiota as an endocrine organ and as a key regulator of the stress response[18,19]. It must also be acknowledged that whilst the microbiota can modulate the stress response, stress can also affect the composition of the gut microbiota[17]. Thus, stress induced changes in the microbiota may precede any subsequent GI and central disturbances in IBS.

Mechanisms

When considering the preclinical evidence reviewed above, and preliminary evidence from healthy humans[142] it appears that the perturbations in composition of the gut microbiota may be considered as a primary factor in driving changes in central function in IBS. However, as IBS is a stress related disorder, the preclinical evidence indicating that chronic stress can alter the gut microbiota must also be borne in mind. As noted, stress and the gut microbiota have been shown to interact in a complex manner to influence brain function, at least in rodents[131] and it will be important to delineate this interaction in IBS. Nevertheless, when considering the gut microbiota as the primary factor in driving changes in central functioning, a number of potential mechanisms have been considered, with varying degrees of evidence supporting both humoral and neural lines of communication to the level of the CNS as well as more localised effects from compositional alterations.

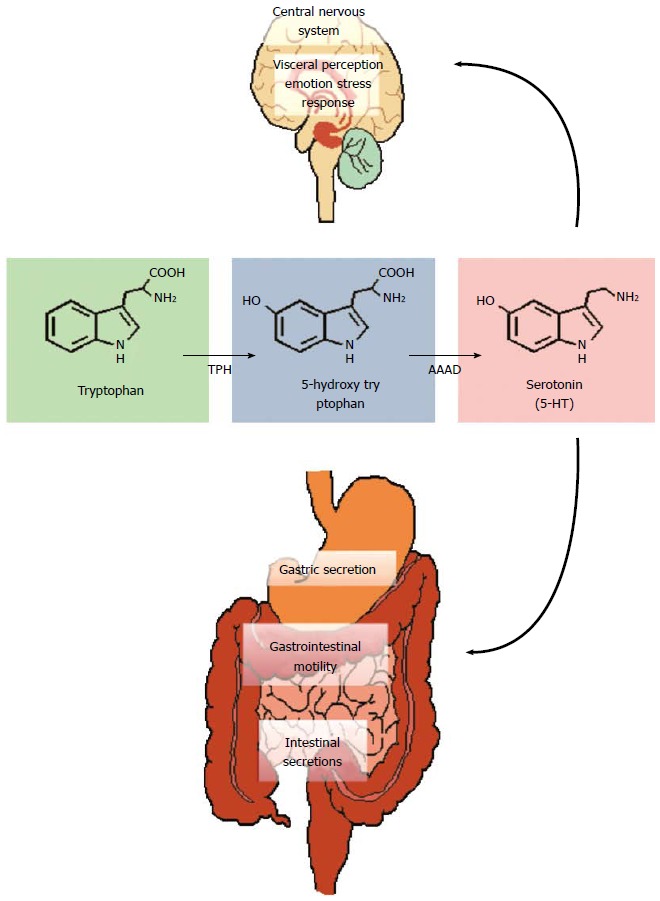

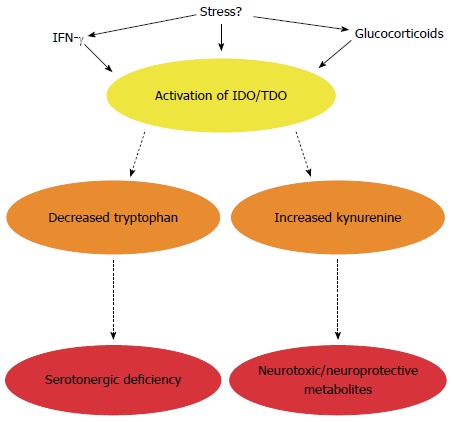

Tryptophan, an essential amino acid and precursor for the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT), in particular has received much attention (Figure 3). 5-HT is a key signalling molecule in the brain-gut axis, both in the enteric nervous system[149] and the CNS[150]. The information gleaned from studies in germ-free animals suggests that the peripheral availability of tryptophan, which is critical for CNS 5-HT synthesis, is coordinated by the gut microbiota[105]. Plasma tryptophan concentrations can be normalised following colonisation of germ-free animals[105] and can also be augmented following administration of the probiotic B. infantis[116]. How the bacteria in our gut regulate circulating tryptophan concentrations is unclear but may involve controlling the degradation of tryptophan along an alternative and physiologically dominant metabolic route, the kynurenine pathway[151,152]. The enzymes responsible for the initial metabolic step in this pathway, indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), are immune and glucocorticoid responsive respectively and the decreased ratio of kynurenine to tryptophan (an index of IDO/TDO activity) in germ-free animals implicates this pathway in the reported alterations (Figure 4)[105]. Moreover, an increased ratio is observed following infection with Trichuris Muris, likely due to increased IDO activity following the associated chronic gastrointestinal inflammation[153].

Figure 3.

Tryptophan metabolism. Tryptophan is converted to 5-hydroxytryptophan by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) and this is the rate limiting step in the pathway. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) subsequently converts 5-HTP into serotonin (5-HT). These reactions occur both in the central nervous system (CNS) (where 5-HT regulates a myriad of functions including emotion, cognition, stress and visceral perception) and in the enteric nervous system (gastrointestinal motility and secretion).

Figure 4.

Impact of altered tryptophan metabolism in irritable bowel syndrome. In addition to serotonin, tryptophan can also be metabolised along the kynurenine pathway to generate neurotoxic and neuroprotective metabolites. The enzymes responsible for degradation along this pathway are immune (indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase, IDO) and stress (tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase, TDO) responsive. In IBS, this pathway is activated leading to a potential serotonergic deficiency and/or altered enteric nervous system (ENS) and central nervous system (CNS) availability of kynurenine and its metabolites. The microbiota appears to directly or indirectly regulate enzyme activity.

The relevance of these preclinical findings to IBS is well reflected in the clinical literature which has demonstrated increased IDO activity in both male and female IBS populations[154-156]. Interestingly, TLR receptors, which have altered expression and activity in both clinical IBS populations[157,158] and animal models of the disorder[159], might drive the low grade inflammation in IBS and mediate the immune consequences of the misfiring engagement between the microbiota and the host in IBS. In this context, it is interesting to note that once TLR receptors are engaged by their cognate ligands, degradation of tryptophan can ensue in general[155,160,161] and there appears to be a differential TLR-specific pattern of kynurenine production in IBS[155].

There are also other potential explanations for the alterations in tryptophan supply due to microbiota alterations and in addition to the growth requirements for bacteria[162], a bacteria-specific tryptophanase enzyme also recruits tryptophan for indole production[163,164]. One such bacteria, Bacteroides fragilis, harbours this enzyme and has recently been linked to gastrointestinal abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders[165]. Of further interest and adding to the complexity of the narrative is that, in contrast to eukaryotes, bacteria retain a capacity for tryptophan biosynthesis via enzymes such as tryptophan synthase[166,167]. It seems a curious quirk of the evolutionary process that we have lost the capacity for endogenous tryptophan synthesis, given the pivotal nature of this amino acid not alone as a precursor to serotonin, which itself has an expansive physiological repertoire[168], but also the other metabolic pathways it serves[150,151].

The production of serotonin from tryptophan, at least in-vitro, is also possible in some bacterial strains[169-171]. Harnessing this knowledge to specifically target the 5-HT receptors and receptor subtypes expressed in the gut of most relevance to IBS[172-175] or indeed alternative receptors activated by kynurenine pathway metabolites that interact with gastrointestinal functions[176] presents an interesting challenge. Similarly, whether we can accurately “titer” the gut microbiota to deliver precise circulating or regional tryptophan concentrations is an intriguing possibility but one beyond our current capabilities.

Of course, immune system mediators and glucocorticoids can impact both locally in the gut and at the level of the CNS independently of their effects on tryptophan metabolism and represent viable alternative routes through which the gut microbiota can modulate gut-brain axis signalling and influence IBS symptoms[14,19,104,177,178]. In addition, the more general concept of a “leaky gut” has been proposed to explain the common feature of a low-grade circulating inflammation in both IBS itself and depression, which, as outlined above, is a prominent psychiatric comorbidity in IBS[179-182]. This model relies on the presence of increased intestinal permeability in IBS which allows the gut microbiota to drive the reported proinflammatory state and influence the CNS via the ensuing elevations in circulating cytokines[104] as well as visceral hypersensitivity via local gut mechanisms[183]. There is certainly accumulating evidence to support the hypothesis of altered intestinal permeability, a compromised integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier and related tight junction disturbances in IBS, if not in depression[183-187].

Defects of the intestinal epithelial barrier may also play a significant role in cognitive dysfunction in IBS. The maternal immune activation (MIA) mouse model produces epithelial barrier defects, changes in the gut microbiota, and associated cognitive and behavioural features of neurodevelopmental disorders in rodents[188]. A recent study has provided strong evidence that maternal infection in the MIA model drives changes in the gut microbiota in the offspring, which subsequently leads to the cognitive and behavioural alterations in this model. Treatment with B. fragillis in MIA offspring restored gut barrier integrity and alleviated some of the cognitive and behavioural defects displayed by these animals[189]. Importantly, restoration of gut barrier integrity in MIA offspring appeared to stop a number of neuroactive metabolites being released systemically to reach the CNS and affect behavioural and cognitive function[189]. Thus, when extrapolated to IBS, epithelial barrier dysfunction may lead to the release of numerous metabolites that could impact centrally and impair cognitive performance. Of note, some probiotic strains have shown efficacy in repairing epithelial barrier function[190] in preclinical models which may also explain the efficacy in treating some GI symptoms in IBS[57]. If probiotics also prove beneficial in alleviating central disturbances in IBS, this may potentially be via restoration of epithelial barrier integrity leading to the reduction of harmful neuroactive metabolites being released from the gut and impacting centrally.

The gut microbiome can also be considered a metabolic organ[191,192] and the array of microbial metabolites produced can impact greatly on GI health and the gut-brain axis scaffolding. Interestingly, dietary restriction of fermentable carbohydrates (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols: the low FODMAP diet) has received much attention for the management of symptoms in IBS[193,194]. Although microbial metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and amino acids by human gut bacteria generates a variety of compounds[195], short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) may be of particular importance in the context of microbiome-gut-brain axis signalling. For example, these organic acids are altered in IBS and may be related to symptoms[52,196]. Preclinically, administration of sodium butyrate increases visceral sensitivity in rats[197]. Interestingly, it has recently been demonstrated that butyrate can regulate intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition[198] which is in line with the proposed epigenetic mechanism of gut-brain axis dysfunction[199,200]. Butyrate can also mediate its immunomodulatory effects via G-protein coupled receptors[201] or indirectly via TLRs[202].

Receptors and transporters for SCFAs are expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and appear to be of relevance to gastrointestinal function[203-208]. For example, SCFAs may modulate both 5-HT secretion[18] and peptide YY release, an important neuropeptide at multiple levels of the gut-brain axis[209]. Thus, there is patently a role for these microbial metabolites beyond the regulation of energy homeostasis[210]. Interestingly, intraventricular administration of propionic acid in rats induces a variety of behavioural alterations although it is unclear if this occurs via similar mechanisms to the periphery[211]. It is worth noting that G protein-coupled receptor (GPR) 41, a receptor activated by propionic acid, is highly expressed in rat brain tissue[212]. Although we know that fibre metabolized by the gut microbiota can increase the concentration of circulating SCFAs[213], it remains to be established if this is reflected at physiologically relevant concentrations in the CNS.

The gut microbiota can also engage neural mechanisms to influence brain-gut axis signalling. In particular, many of the behavioural effects of specific probiotic strains are abolished in vagotomized animals[113,115]. Germ-free studies have confirmed that the presence of intestinal bacteria is also essential for normal postnatal development of the ENS[214] and for normal gut intrinsic primary afferent neuron excitability in the mouse[215]. Thus, there is direct evidence of bacterial communication to the enteric nervous system while as indicated above, the microbiota is also a potential source of relevant ENS neurotransmitters including serotonin and GABA[216-218]. Interestingly, colorectal distension induces specific of patterns of prefrontal cortex activation in the viscerally hypersensitive maternal separation model of IBS, in which microbiota alterations are also manifested[219]. Taken together, it seems likely that the gut microbiota can modulate both the physiological information flow to the CNS via vagal afferents and the noxious information that is encoded by spinal afferents[10,220].

Implications and perspectives

Human microbiome science has become a focal point across multiple research domains and is now a mainstream endeavour. The benefits of the associated theoretical, practical and technological advances can be accrued to advance research in IBS. From a diagnostic perspective, it is difficult on the basis of the present clinical data to pinpoint with accuracy a microbiota-derived signature of IBS. Conceptually, the notion of the microbial community as a pathological entity is challenging for traditional biomarker approaches. Moreover, it is unclear if the current subtyping of IBS according to the dominant bowel habit aligns with specific alterations in the microbiota. In fact, research points to subtypes defined by the microbiota which are bowel-habit independent[27,50,221]. The constant stream of improvements in the technology used to qualitatively and quantitatively describe the gut microbiome make it likely that if a microbiota-based biosignature is present, it will be uncovered[49]. However, the challenges associated with analysis of these datasets should not be underestimated and it will be interesting to see if a format can be devised which would facilitate more routine and affordable screening.

The fact that the composition of the gut microbiota is malleable make it an interesting therapeutic target. Of the options available, certain probiotic strains have already shown some potential[57] while antibiotics also seem beneficial in some cases[222]. Probiotics are probably the more appealing option given their long record of safety although as for their efficacy, this does need to be evaluated on a strain-by-strain basis[223]. Prebiotics should also be considered on the basis of some studies indicating efficacy in the treatment of GI symptoms in IBS[224-226], and preclinical data indicating that prebiotic administration can modulate levels of important cognitive and behavioural related neurotrophins such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glutamatergic receptor expression[227]. Diet offers an alternative mechanism to sculpt the gut microbiome[44] although it is difficult to grapple with the subtleties of using the approach to engender a switch from a “diseased” to a “healthy” microbiota. It is also worth noting the capacity of the gut microbiota to metabolise dietary components and associated health consequences, as in the case of L-carnitine which is associated with cardiovascular risk[228].

There is much current interest in the therapeutic potential of faecal microbiota transplantation[229]. This has largely stemmed from the demonstrated efficacy of donor faecal infusions in the treatment of recurrent C. difficile[230-232]. However, there are legitimate safety concerns regarding, for example, the provenance of the donor sample. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has taken a two track approach to its regulation strategy, opting not to enforce an investigational new drug (IND) requirement for use in C. difficile infections but adopting a stricter policy for other indications[229]. The IND requirement is an onerous and time consuming process which may impede or delay the emergence of FMT as a potential treatment option for IBS, if indeed it does prove effective. However, it is interesting to note the emergence of stool banks like OpenBiome (http://www.openbiome.org/) that provide screened, filtered, and frozen material ready for clinical use in the treatment of C. difficile. It is thus likely an extensive infrastructure will already be in place by the time FMT is more fully evaluated in IBS.

The contribution of the gut microbiome to drug metabolism, with potential implications for efficacy and toxicity, is also an emerging area of interest[233]. Recently, for example, it has been demonstrated that digoxin, a cardiac drug, can be inactivated by the gut Actinobacterium Eggerthella lenta[234]. Whether specific enzyme targets expressed by the microbiota can be selectively targeted to achieve desirable clinical outcomes is an interesting question[235] and may be of relevance to IBS. Clearly, achieving a superior mechanistic understanding of how the gut microbiota directly and indirectly affects drug metabolism could be of great benefit[236]. This is likely a bidirectional relationship with host-targeted drugs also modulating the composition and activity of the gut microbiome[237]. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the adverse impact of olanzapine (an antipsychotic) on metabolic function, possibly mediated by alterations in microbiota composition, can be attenuated by concurrent antibiotic administration in rats[238,239]. Some members of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may also possess antimicrobial activity[240]. This will need to be considered in the context of antidepressant agents used to treat IBS[241] or in any renewed attempts to more successfully target specific serotonergic receptors in the future[174,242]. The therapeutic potential in targeting microbial metabolites or their receptors (e.g. SCFAs) also warrants consideration[243].

CONCLUSION

There are biologically plausible mechanisms through which the gut microbiome can influence both the cardinal symptoms and other prominent features of IBS. Moreover, the outcomes of a variety of experimental strategies offer convincing evidence that this is indeed the case. Although no consensus exists on the precise compositional alteration of the gut microbiota, the clinical data converges to support the concept of a less diverse and unstable community of bacteria in the disorder. While a causal role is yet to be verified clinically, it seems likely that this will be addressed once the necessary longitudinal studies are embraced. Moving forward the concept of IBS as a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder offers a solid framework to further advance our understanding of the disorder. This approach promises much needed diagnostic and therapeutic innovations, but requires a continued concerted effort from researchers and clinicians across multiple disciplines.

Footnotes

Supported by Science Foundation Ireland, No. SFI/12/RC/2272, No. 02/CE/B124, No. 07/CE/B1368; Health Research Board No. HRA_POR/2011/23; Brain and Behaviour Research Foundation No. 20771

P- Reviewer: Bellini M, Chiba T, Gazouli M, Hauser G, Lee YY, Sinagra E S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Wilson A, Longstreth GF, Knight K, Wong J, Wade S, Chiou CF, Barghout V, Frech F, Ofman JJ. Quality of life in managed care patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Manag Care Interface. 2004;17:24–28, 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood JD. Taming the irritable bowel. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:142–156. doi: 10.2174/13816128130119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quigley EM, Abdel-Hamid H, Barbara G, Bhatia SJ, Boeckxstaens G, De Giorgio R, Delvaux M, Drossman DA, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Guarner F, et al. A global perspective on irritable bowel syndrome: a consensus statement of the World Gastroenterology Organisation Summit Task Force on irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:356–366. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318247157c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilleri M. Peripheral mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1626–1635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1207068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quigley EM. Changing face of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:453–466. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke G, Quigley EM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Irritable bowel syndrome: towards biomarker identification. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:478–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grenham S, Clarke G, Cryan J, Dinan TG. Brain-Gut-Microbe Communication in Health and Disease. Frontiers in Gastrointestinal Science. 2011:In Press. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:306–314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bercik P, Collins SM, Verdu EF. Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterol Moti. 2012;24:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moloney RD, Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The microbiome: stress, health and disease. Mamm Genome. 2014;25:49–74. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Mahony SM, Hyland NP, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Maternal separation as a model of brain-gut axis dysfunction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:71–88. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tannock GW, Savage DC. Influences of dietary and environmental stress on microbial populations in the murine gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun. 1974;9:591–598. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.3.591-598.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P, Codling C, Ceolho AM, Quigley EM, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans JM, Morris LS, Marchesi JR. The gut microbiome: the role of a virtual organ in the endocrinology of the host. J Endocrinol. 2013;218:R37–R47. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Mäkivuokko H, Rinttilä T, Paulin L, Corander J, Malinen E, Apajalahti J, Palva A. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerckhoffs AP, Samsom M, van der Rest ME, de Vogel J, Knol J, Ben-Amor K, Akkermans LM. Lower Bifidobacteria counts in both duodenal mucosa-associated and fecal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2887–2892. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malinen E, Rinttilä T, Kajander K, Mättö J, Kassinen A, Krogius L, Saarela M, Korpela R, Palva A. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mättö J, Maunuksela L, Kajander K, Palva A, Korpela R, Kassinen A, Saarela M. Composition and temporal stability of gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome--a longitudinal study in IBS and control subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;43:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maukonen J, Satokari R, Mättö J, Söderlund H, Mattila-Sandholm T, Saarela M. Prevalence and temporal stability of selected clostridial groups in irritable bowel syndrome in relation to predominant faecal bacteria. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55:625–633. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffery IB, Quigley EM, Öhman L, Simrén M, O’Toole PW. The microbiota link to irritable bowel syndrome: an emerging story. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:572–576. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Malinen E, Aarnikunnas J, Tuimala J, Paulin L, Mäkivuokko H, Kajander K, Palva A. Microbial community analysis reveals high level phylogenetic alterations in the overall gastrointestinal microbiota of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffery IB, O’Toole PW, Öhman L, Claesson MJ, Deane J, Quigley EM, Simrén M. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61:997–1006. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajilić-Stojanović M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, Kajander K, Kekkonen RA, Tims S, de Vos WM. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1792–1801. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Codling C, O’Mahony L, Shanahan F, Quigley EM, Marchesi JR. A molecular analysis of fecal and mucosal bacterial communities in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:392–397. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Keku TO, Chang YH, Packey CD, Sartor RB, Ringel Y. Molecular analysis of the luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G799–G807. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00154.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noor SO, Ridgway K, Scovell L, Kemsley EK, Lund EK, Jamieson C, Johnson IT, Narbad A. Ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel patients exhibit distinct abnormalities of the gut microbiota. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkes GC, Rayment NB, Hudspith BN, Petrovska L, Lomer MC, Brostoff J, Whelan K, Sanderson JD. Distinct microbial populations exist in the mucosa-associated microbiota of sub-groups of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saulnier DM, Riehle K, Mistretta TA, Diaz MA, Mandal D, Raza S, Weidler EM, Qin X, Coarfa C, Milosavljevic A, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiome signatures of pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1782–1791. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigsbee L, Agans R, Shankar V, Kenche H, Khamis HJ, Michail S, Paliy O. Quantitative profiling of gut microbiota of children with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1740–1751. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salonen A, Nikkilä J, Immonen O, Kekkonen R, Lahti L, Palva A, de Vos WM. Intestinal microbiota in healthy adults: temporal analysis reveals individual and common core and relation to intestinal symptoms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malinen E, Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Nikkilä J, Jääskeläinen A, Rinttilä T, Vilpponen-Salmela T, von Wright AJ, Palva A. Association of symptoms with gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4532–4540. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pimentel M, Talley NJ, Quigley EM, Hani A, Sharara A, Mahachai V. Report from the multinational irritable bowel syndrome initiative 2012. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:e1–e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Toole PW. Changes in the intestinal microbiota from adulthood through to old age. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 4:44–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parfrey LW, Knight R. Spatial and temporal variability of the human microbiota. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 Suppl 4:8–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bäckhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, Sanders ME, Sartor RB, Sherman PM, Versalovic J, Young V, Finlay BB. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome: current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moschen AR, Wieser V, Tilg H. Dietary Factors: Major Regulators of the Gut’s Microbiota. Gut Liver. 2012;6:411–416. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.4.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes P, Corish C, O’Mahony E, Quigley EM. A dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27 Suppl 2:36–47. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carroll IM, Chang YH, Park J, Sartor RB, Ringel Y. Luminal and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Pathog. 2010;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerckhoffs AP, Ben-Amor K, Samsom M, van der Rest ME, de Vogel J, Knol J, Akkermans LM. Molecular analysis of faecal and duodenal samples reveals significantly higher prevalence and numbers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in irritable bowel syndrome. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:236–245. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.022848-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fraher MH, O’Toole PW, Quigley EM. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: a guide for the clinician. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:312–322. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clarke G, O’Toole PW, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Characterizing the Gut Microbiome: Role in Brain-Gut Function. In: Coppola G, editor. The OMICS: Applications in Neuroscience: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jalanka-Tuovinen J, Salojärvi J, Salonen A, Immonen O, Garsed K, Kelly FM, Zaitoun A, Palva A, Spiller RC, de Vos WM. Faecal microbiota composition and host-microbe cross-talk following gastroenteritis and in postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2014;63:1737–1745. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ponnusamy K, Choi JN, Kim J, Lee SY, Lee CH. Microbial community and metabolomic comparison of irritable bowel syndrome faeces. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:817–827. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.028126-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tana C, Umesaki Y, Imaoka A, Handa T, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S. Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:512–519, e114-e115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Power SE, O’Toole PW, Stanton C, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF. Intestinal microbiota, diet and health. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:387–402. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513002560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Vos WM, de Vos EA. Role of the intestinal microbiome in health and disease: from correlation to causation. Nutr Rev. 2012;70 Suppl 1:S45–S56. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spiller R, Lam C. An Update on Post-infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Role of Genetics, Immune Activation, Serotonin and Altered Microbiome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:258–268. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2012.18.3.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marshall JK, Thabane M, Garg AX, Clark WF, Salvadori M, Collins SM. Incidence and epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome after a large waterborne outbreak of bacterial dysentery. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:445–450; quiz 660. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Quigley EM. Review article: probiotics for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome--focus on lactic acid bacteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shanahan F, Quigley EM. Manipulation of the microbiota for treatment of IBS and IBD-challenges and controversies. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1554–1563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, Gundrum JD. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, Mareya SM, Shaw AL, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pimentel M, Morales W, Chua K, Barlow G, Weitsman S, Kim G, Amichai MM, Pokkunuri V, Rook E, Mathur R, et al. Effects of rifaximin treatment and retreatment in nonconstipated IBS subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2067–2072. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quigley EM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: what it is and what it is not. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:141–146. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Candela M, Biagi E, Maccaferri S, Turroni S, Brigidi P. Intestinal microbiota is a plastic factor responding to environmental changes. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenwood-van Meerveld B. Importance of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors on intestinal afferents in the regulation of visceral sensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19 Suppl 2:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quigley EM. Disturbances of motility and visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome: biological markers or epiphenomenon. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:221–233, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talley NJ, Spiller R. Irritable bowel syndrome: a little understood organic bowel disease? Lancet. 2002;360:555–564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09712-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crouzet L, Gaultier E, Del’Homme C, Cartier C, Delmas E, Dapoigny M, Fioramonti J, Bernalier-Donadille A. The hypersensitivity to colonic distension of IBS patients can be transferred to rats through their fecal microbiota. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:e272–e282. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verdú EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, Huang XX, Blennerhassett P, Jackson W, Mao Y, Wang L, Rochat F, Collins SM. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006;55:182–190. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bercik P, Verdú EF, Foster JA, Lu J, Scharringa A, Kean I, Wang L, Blennerhassett P, Collins SM. Role of gut-brain axis in persistent abnormal feeding behavior in mice following eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R587–R594. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90752.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ibeakanma C, Miranda-Morales M, Richards M, Bautista-Cruz F, Martin N, Hurlbut D, Vanner S. Citrobacter rodentium colitis evokes post-infectious hyperexcitability of mouse nociceptive colonic dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Physiol. 2009;587:3505–3521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]