Abstract

AIM: To report the clinical impact of adrenal endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the evaluation of patients with adrenal gland enlargement or mass.

METHODS: In a retrospective single-center case-series, patients undergoing EUS-FNA of either adrenal gland from 1997-2011 in our tertiary care center were included. Medical records were reviewed and results of EUS, cytology, adrenal size change on follow-up imaging ≥ 6 mo after EUS and any repeat EUS or surgery were abstracted. A lesion was considered benign if: (1) EUS-FNA cytology was benign and the lesion remained < 1 cm from its original size on follow-up computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging or repeat EUS ≥ 6 mo after EUS-FNA; or (2) subsequent adrenalectomy and surgical pathology was benign.

RESULTS: Ninety-four patients had left (n = 90) and/or right (n = 5) adrenal EUS-FNA without adverse events. EUS indications included: cancer staging or suspected recurrence (n = 31), pancreatic (n = 20), mediastinal (n = 10), adrenal (n = 7), lung (n = 7) mass or other indication (n = 19). Diagnoses after adrenal EUS-FNA included metastatic lung (n = 10), esophageal (n= 5), colon (n = 2), or other cancer (n = 8); benign primary adrenal mass or benign tissue (n = 60); or was non-diagnostic (n = 9). Available follow-up confirmed a benign lesion in 5/9 non-diagnostic aspirates and 32/60 benign aspirates. Four of the 60 benign aspirates were later confirmed as malignant by repeat biopsy, follow-up CT, or adrenalectomy. Adrenal EUS-FNA diagnosed metastatic cancer in 24, and ruled out metastasis in 10 patients. For the diagnosis of malignancy, EUS-FNA of either adrenal had sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of 86%, 97%, 96% and 89%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Adrenal gland EUS-FNA is safe, minimally invasive and a sensitive technique with significant impact in the management of adrenal gland mass or enlargement.

Keywords: Adrenal gland neoplasms/diagnosis, Adrenal glands/pathology, Adrenal gland/ultrasonography, Adrenal gland neoplasms/secondary, Endosonography, Biopsy, Fine-needle

Core tip: Studies evaluating endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of the adrenal gland generally include patients with underlying malignancy only and most lack follow-up for benign lesions. We report the clinical utility of adrenal gland EUS-FNA in a retrospective study that included 94 patients who underwent EUS-FNA of either adrenal for various indications and provide follow-up information for those with benign EUS-FNA cytology results. For the diagnosis of malignancy, EUS-FNA of either adrenal had sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of 86%, 97%, 96% and 89%, without serious adverse events.

INTRODUCTION

The development of modern imaging techniques such as ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has led to increased detection of adrenal masses, which are found in up to 5% of patients undergoing CT of the abdomen[1]. The incidence of an adrenal incidentaloma (detection of an otherwise unsuspected adrenal mass on imaging), ranges from 0.2%-7% as reported in autopsy series[2]. Most of these incidentally found lesions are non-functioning adenomas, but 2% are metastatic lesions[3].

About 75% of adrenal masses identified during staging of patients with cancer are metastatic lesions which are most commonly metastases from lung, breast, stomach and kidney, as well as, melanomas and lymphomas[2]. The sensitivity and specificity of imaging techniques are currently insufficient to differentiate benign from malignant masses, therefore, patients with a high index of suspicion for malignancy are often referred for percutaneous biopsy[4].

Image-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA), using either ultrasound (US) or CT and percutaneous approach, have traditionally been used for sampling of the adrenal glands[5,6]. However, this technique yields non-diagnostic samples in up to 14% of patients and is associated with adverse events in 0.4%-12%[7,8].

Endoscopic ultrasound guided-fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of either adrenal offers a minimally invasive and accurate method for sampling the adrenals with a low risk profile[3,9-12]. However, studies to date have mostly included patients with underlying malignancy and the great majority lack follow-up imaging for benign lesions or include follow-up for few patients[4,12,13]. This study reports the utility of EUS-FNA in patients with known adrenal gland enlargement or a mass, and the impact of the EUS-FNA cytology result on patient care, final diagnosis and adverse events from the procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective single-center case series was approved by the institutional Review Boards at the Indiana University Health School of Medicine in Indianapolis Indiana. Cytology and EUS databases between October 1997 and December 2011 were reviewed to identify all patients who underwent EUS-FNA of either adrenal gland. The original 38 patients were previously described in a 2007 publication from our hospital[3]. Medical records were reviewed and results of imaging (CT and MRI) prior to the procedure, EUS indications and findings, cytological investigations and complications were recorded. In addition, follow-up clinical information and any repeat adrenal imaging or surgery of the adrenal gland was abstracted. For patients without available follow-up on our medical records, referring physicians were contacted by phone to obtain this information. Through institutional protocol, all patients were called within 48 h after EUS to assess for any short-term adverse events not already identified. Adverse events were defined as: systolic blood pressure less than 80 mmHg at any time during the procedure, hypoxemia (oxygen saturation less than 85% on room air or on baseline oxygen supplementation), bradycardia (heart rate less than 50 beats per minute), bleeding recognized during EUS or subsequent imaging studies with hemoglobin drop of ≥ 2 g/dL from baseline, need for blood transfusion within 48 h of the procedure, pneumothorax, abdominal pain, hypertensive urgency and, requirement for hospitalization.

EUS

After obtaining written informed consent, patients received conscious sedation using various combinations of intravenous midazolam, meperidine, fentanyl or propofol under appropriate cardiorespiratory monitoring. All procedures were done by or under the supervision of one of seven attending endoscopists. Radial endosonography (Olympus GFUM-20, GFUM-130, GFUM-160 or GFUE160-AL5; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA; United States), was performed initially in some patients. Linear EUS (Olympus GF-UC30P, Olympus GF-UC140P, or Pentax 32-UA or 36-UX; Pentax Medical, Montvale, NJ; United States), was performed in all patients.

The left adrenal gland was visualized by one of 2 methods. First, the descending aorta was followed to the celiac axis; once this was seen, the left adrenal gland was visualized after a slight clockwise rotation and withdrawal movement. Alternatively, the splenic vein posterior to the body of the pancreas was identified by transgastric imaging; clockwise rotation and withdrawal of the echo endoscope following the splenic vein laterally then permitted the identification of the left adrenal gland superior to the upper pole of the left kidney. Transduodenal imaging of the right adrenal gland with EUS was performed with the echoendoscope in the long position along the greater curvature of the stomach. The inferior vena cava or the right kidney was then visualized, and then right adrenal gland was uniformly present between the superior pole of the right kidney, the liver and the inferior vena cava. EUS exams for patients in this study attempted to image a known or suspected adrenal mass or enlargement and did not routinely attempt to visualize both adrenal glands

The size of the adrenal gland for study purposes was the maximal cross-sectional diameter of the gland. An adrenal gland mass was considered to be a focal enlargement of the gland with a notable discrete mass, whereas, adrenal gland enlargement was considered when the gland was diffusively increased size without a visible discrete mass.

EUS-FNA was performed using a 19, 22 or 25 gauge, 8 cm needle (Cook-Medical, Winston-Salem, NC; United States or Boston Scientific, Natick, MA; United States). Minimal clotting parameters required to perform EUS-FNA were a platelet count of ≥ 50000 and INR ≤ 1.5. Color Doppler imaging was used to ensure the absence of intervening vascular structures along the anticipated needle path. After needle puncture of the adrenal gland, the stylet was removed. At the discretion of the endosonographer, suction was applied to the proximal end of the needle with a vacuum containing syringe. If excess blood was present in the initial specimen, subsequent passes with the same needle were attempted without suction. There was no maximum number of biopsy attempts allowed. Biopsy attempts were performed at the discretion of the endosonography until considered that useful clinical information was provided, or that further attempts would be futile. According to our routine endoscopy unit protocol, patients were monitored in the recovery area after EUS imaging for at least 60 min before discharge. No additional monitoring was performed after adrenal biopsy.

Cytological examination

Aspirates were expressed and smeared onto 2 glass slides. One slide was air-dried and stained with a modified Giemsa stain for on-site interpretation, while the other slide was alcohol-fixed and stained using the Papanicolaou method. A cytotechnologist and/or cytopathologist, not blinded to the patient’s clinical history, were available on-site for real-time preliminary interpretation for all procedures; this added an additional 2-3 min to the procedure for each FNA pass. Additional aspirates were submitted for immunocytochemical analysis at the discretion of the cytopathologist to confirm metastatic malignancy when required.

Cytology reports were characterized as “diagnostic for malignancy”, “benign adrenal tissue”, or “non-diagnostic”. The following were considered to be cytologic features of benign adrenocortical tissue: clusters of cells with a foamy cytoplasm and smoothly contoured, round to oval nuclei, all within a vacuolated or foamy background with occasional single cells[13]. Diagnostic cytology specimens were considered to include any of the following: benign-appearing cytologic features of the adrenal gland, primary adrenal neoplastic tissue, or metastatic malignant cells. Non-diagnostic cytology specimens had none of these three features but did show any of the following: amorphous debris, blood, or gastric contaminant.

Study definitions

The final diagnosis was made on the basis of the surgical pathology if resection was performed, unequivocal cytology from EUS-FNA, clinical follow-up, or the stability of lesion size as assessed by subsequent imaging studies. An adrenal lesion was considered stable (and therefore benign) if size was within 1 cm by follow-up imaging (CT or MRI) obtained at least 6 mo after EUS-FNA[14]. EUS-FNA of either adrenal gland was considered to have had an impact on patient care if the cytology resulted in either: (1) benign cytology which excluded adrenal metastasis and permitted resection of the primary tumor; or (2) initial diagnosis of malignancy, distant metastasis, tumor recurrence or primary adrenal neoplasm.

Statistical analysis

For analysis, continuous variables were described as means and standard deviations, and dichotomous variables were expressed as simple proportions, with or without 95%CI. Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact tests were used to test for differences in comparisons between continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. For calculating test characteristics of EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of malignancy, only aspirates interpreted as diagnostic for malignancy on cytological examination were considered as true positives. Patients with subsequent adrenalectomy, percutaneous adrenal biopsies or follow-up abdominal imaging of the adrenal at least 6 mo after EUS were utilized to calculate the test characteristics of EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of non-malignant (benign or non-diagnostic) specimens. 95% confidence intervals were calculated when appropriate. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

94 consecutive patients (52% men; median age: 66 years, range 32-86) underwent 95 attempted EUS-FNA of the left (n = 90) and/or right (n = 5) adrenal gland during the study period. There were no adverse events related to these procedures. Patient characteristics and EUS findings by results of diagnostic and non-diagnostic biopsies are summarized in Table 1. Patients with diagnostic malignant biopsies had smaller lesions than those with diagnostic benign lesions (P = 0.027) otherwise the clinical and EUS features of the two groups were similar. Indications for EUS in all 94 patients are summarized in Table 2. Known adrenal gland enlargement, fullness or mass according to previous imaging was present in 55 (59%). A previous diagnosis of cancer was present in 40 patients (42%) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and endoscopic ultrasound findings n (%)

| Characteristics |

Diagnostic

(n = 85) |

Non-diagnostic (n = 9) | P value | |

| Benign (n = 60) | Malignant (n = 25) | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 67 ± 11 | 63 ± 14 | 0.161 | |

| 66 ± 12 | 66 ± 11 | 0.992 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 57 (95) | 25 (100) | 7 (78) | |

| African American | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Gender | ≥ 0.993 | |||

| Male | 26 (27) | 19 (20) | 5 (5) | |

| Female | 34 (36) | 6 (7) | 4 (5) | |

| Adrenal biopsied | ≥ 0.994 | |||

| Left | 58 (61) | 23 (24) | 9 (10) | |

| Right | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| EUS image of adrenal | ||||

| Mass | 49 (52) | 25 (26) | 6 (6) | 0.145 |

| Diffuse enlargement | 11 (12) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.096 |

| Size by EUS, cm | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 0.0277 | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 0.418 | |

| Range | 0.7-5.2 | 1.3-7.0 | 1.0-4.0 | |

| Echogenicity | ||||

| Hypoechoic | 40 (42) | 22 (24) | 4 (4) | |

| Hyperechoic | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.149 |

| Not reported or unavailable | 19 (20) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | |

| Number of FNA passes | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 1.5 | 0.461 |

Mean age diagnostic vs non-diagnostic;

Diagnostic vs non-diagnostic cytology result based on gender;

Adrenal Gland FNA side and Diagnostic vs non-diagnostic cytology result;

Presence or absence of an adrenal mass and diagnostic vs non-diagnostic cytology result;

Presence of absence of an adrenal mass and benign vs malignant FNA cytology;

Median size by EUS (cm) and malignant vs benign FNA cytology;

Median size by EUS (cm) and Diagnostic vs non-diagnostic cytology;

Adrenal Echogenicity on EUS and Diagnostic vs non-diagnostic cytology;

Number of FNA passes; and Diagnostic vs non-diagnostic FNA; 10Mean age benign vs malignant. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; FNA: Fine-needle aspiration.

Table 2.

Indications for endoscopic ultrasound

| Indication for EUS | n (%) |

| Cancer staging1 | 26 (27) |

| Suspected cancer recurrence2 | 5 (6) |

| Abnormal CT/PET-CT or MRI | |

| Pancreatic mass | 20 (21) |

| Mediastinal mass | 10 (11) |

| Lung mass | 7 (7) |

| Adrenal mass | 7(7) |

| Gastric mass | 2 (2) |

| Liver mass | 3 (3) |

| Kidney mass | 1 (1) |

| Retroperitoneal mass | 1 (1) |

| Other3 | 12 (13) |

| Total of patients | 94 |

Esophageal cancer (n = 3), gastric cancer (n = 2), breast (n = 1), jejunal adenocarcinoma (n = 1), renal cell cancer (n = 2), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 1), lung cancer (n = 16); 2Suspected recurrence of oral cancer (n = 1), breast cancer (n = 1), hepatoma (n = 1), lung adenocarcinoma (n = 1), esophageal adenocarcinoma (n = 1);

Chronic pancreatitis (n = 3), abnormal upper endoscopy (n = 3), common bile duct stricture (n = 2), celiac nerve block (n = 1), suspected metastatic disease on imaging (n = 1), Barrett’s esophagus with high grade dysplasia (n = 1), ectatic pancreatic duct (n = 1). EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; PET: Positron emission tomography; CT: Computed tomography.

Table 3.

Previous diagnosis of cancer in patients undergoing endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration

| Previous diagnosis of cancer (n = 40) | Benign cytology on EUS-FNA (n = 21) | Malignant cytology on EUS-FNA (n = 15) | Non-diagnostic cytology on EUS-FNA (n = 4) |

| Penile cancer | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Oral SCC | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lung cancer | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Esophageal ADC | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Breast cancer | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Gastric ADC | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pulmonary carcinoid | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Colon ADC | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SCC of the duodenum | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Basal cell cancer of the skin | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bladder cancer | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Melanoma | 0 | 1 | 0 |

EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration; SCC: Squamous cell carcinoma; ADC: Adenocarcinoma.

Prior attempt with percutaneous CT-guided approach for adrenal biopsy was performed and unsuccessful in 3 patients, two of them subsequently had a diagnostic adrenal EUS-FNA (1 malignant, 1 benign); the third patient had a non-diagnostic EUS-FNA of the adrenal gland.

EUS findings and cytology

The mean maximal diameters for the right and left adrenal masses were 3.5 ± 0.88 cm and 2.72 ± 1.36 cm, respectively. EUS identified an adrenal mass in the 5 (100%) patients who underwent right adrenal EUS-FNA and in 75/90 (83%) who underwent left EUS-FNA. The left 15 adrenals without mass demonstrated only diffuse enlargement (one patient had bilateral adrenal EUS-FNA) (Table 1).

Nine aspirations were non-diagnostic (9.5%). Four of these, had a previous diagnosis of cancer and 6 had an identified adrenal mass during EUS with a mean mass diameter of 2.4 ± 1.2 cm. Non-diagnostic aspirations occurred mostly before 2004, however the frequency before and after 2004 was not different (P = 0.14), and this was considered to be related to operator’s learning curve (Table 4).

Table 4.

Timing of diagnostic and non-diagnostic biopsies n (%)

| Timing of EUS-FNA | Diagnostic EUS-FNA | Non diagnostic EUS-FNA | Total EUS-FNA |

| Before 01/2004 | 31 (33) | 6 (7) | 37 |

| After 2004 | 54 (57) | 3 (3) | 57 |

| Total | 85 (90) | 9 (10) | 94 |

Non diagnostic EUS-FNA before 2004 vs after 2004 (P = NS). EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration.

Diagnostic cytology was obtained in 86 biopsies after a mean of 3.2 ± 1.4 needle passes. There was no statistical significance between the number of needle passes for diagnostic biopsies and non-diagnostic biopsies (P = 0.98). All nondiagnostic biopsies were from the left adrenal gland; all right adrenal biopsies were diagnostic. Ninety-one fine-needle aspirations were performed with a 22G needle and included all the specimens that yielded a non-diagnostic sample. Only 3 and 1 biopsies on these series were obtained with a 25 G and a 19 G needle, respectively.

Adrenal gland FNA was malignant in 26% (n = 25) and benign in 64% (n = 60). Details about adrenal gland EUS-FNA cytology results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cytology results from adrenal gland endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration

| EUS-FNA cytologic diagnosis |

| Malignant EUS-FNA cytology (26%, n = 25) |

| Metastatic lung cancer |

| Metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma |

| Metastatic colon adenocarcinoma |

| Metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

| Metastatic breast adenocarcinoma |

| Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma |

| Metastatic melanoma |

| Metastatic oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma |

| Benign EUS-FNA cytology (64%, n = 60) |

| Benign adrenal tissue |

| Aldosteronoma |

| Paraganglioma |

| Pheochromocytoma1 |

Previously negative normal plasma catecholamines and, 24-h urine normetanephrines, vanillylmandelic acid and metanephrines. EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration.

Clinical follow-up

Follow-up was available for 36/60 (60%) patients with benign adrenal cytology. The remaining 24 patients either were: lost to follow-up (n = 4), did not get repeat adrenal gland imaging (n = 5) or died (n = 15). The 15 patients died a mean of 28 ± 36 mo after EUS without follow imaging.

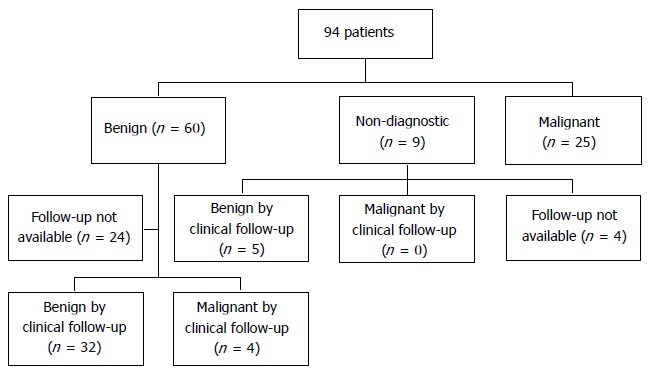

Available follow-up for 5/9 (55%) patients with non-diagnostic biopsies, demonstrated a stable adrenal lesion on repeat CT or MRI; the remaining four died before follow-up imaging (Figure 1). Median follow-up for benign and non-diagnostic biopsies was 24 mo (range 4-96) and 12 mo (range 7-36), respectively.

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart .

In 36 patients with benign adrenal cytology, available follow-up from imaging in 28 showed a stable adrenal lesion on CT (n = 27) or repeat EUS (n = 1). Five additional patients underwent adrenalectomy and without repeat imaging in 4. In these five, surgical pathology was benign in 4 and demonstrated an adrenocortical carcinoma in 1 (Table 6). For the remaining three, 2 had subsequent CT-guided adrenal biopsy showing metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in one (4 mo after EUS) and large cell neuroendocrine tumor in another (EUS-FNA biopsy of the pancreas had previously showed neuroendocrine tumor). Finally, one patient had follow-up CT 6 mo after EUS that demonstrated a new contralateral adrenal mass with findings of metastatic disease to the adrenals (Table 6).

Table 6.

Final diagnosis for patients with non-malignant biopsies for who follow up was available

| Final diagnosis | Benign FNA | Non-diagnostic FNA |

| Confirmed benign on follow up | 321 | 51 |

| Confirmed malignant on follow up | 42 | 0 |

| Total of patients with follow up | 36 | 5 |

Follow up CT;

Subsequent CT-guided adrenal biopsy (n = 2), enlargement on repeat CT (n = 1) or adrenalectomy (n = 1). FNA: Fine-needle aspiration; CT: Computed tomography.

In one additional patient with history of melanoma, CT scan for surveillance revealed a left adrenal mass. EUS-FNA of the mass was malignant, however, adrenalectomy 1 mo later showed benign pathology.

Clinical impact of EUS-FNA

For the diagnosis of malignancy EUS-FNA of the adrenal gland had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of 86% (95%CI: 68%-95%), 97% (95%CI: 83%-100%), 96% (95%CI: 79%-100%) and 89% (95%CI: 74%-96%), respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of adrenal gland EUS-FNA for benign lesions was 97% (95%CI: 83%-100%), 86% (95%CI: 68%-95%), 89% (95%CI: 74%-96%) and 96% (95%CI: 79%-100%), respectively.

The diagnostic accuracy of adrenal gland EUS-FNA was 92% for both benign and malignant lesions.

Only 2 patients died within 6 mo of the procedure. If these two were hypothetically included as false-negative biopsies, test characteristics for the diagnosis of malignancy would change to: sensitivity 80%, specificity 97%, positive predictive value 96% and negative predictive value to 84%.

In patients with benign adrenal gland cytology, EUS-FNA ruled out adrenal metastasis in 10 patients with underlying malignancy available follow-up (adrenalectomy or follow-up imaging). EUS-FNA of the adrenal gland made the initial diagnosis of stage IV cancer in 18 patients (lung cancer in 10, undifferentiated carcinoma in 1 and, esophageal in 4, colon in 2 and pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 1), and initial diagnosis of cancer recurrence in 6 patients (RCC in 2, oral SCC in 1, HCC in 1, esophageal cancer in 1 and breast cancer in 1).

Benign cytology and exclusion of metastases in 10/36 patients with malignancy or a precancerous lesion (non-small cell cancer in 7, gastrointestinal stromal tumor in 1, esophageal adenocarcinoma in 1, and gastric adenocarcinoma in 1) permitted subsequent surgery. EUS-FNA of the adrenal gland confirmed an initial diagnosis of unsuspected pheochromocytoma in one patient. Finally, unnecessary surgery was avoided in 18 patients with metastatic disease and 6 patients with cancer recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Adrenal gland adenomas are discovered in 5% of abdominal CT exams, in 2%-9% of autopsy studies and up to 4%-7% of patients with potentially resectable lung cancer, therefore accurate characterization of these lesions in cancer patients is essential[12,15]. Unfortunately, sensitivity and specificity of imaging techniques are currently insufficient to differentiate benign from malignant masses and, false-negative and false-positive rates by CT scan both average 10%[4].

Distinguishing a metastatic lesion from a primary adrenal tumor is aided by the knowledge of past cancer type and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is increasingly used in restaging protocols for FDG-avid malignant tumors and can aid to document other extra-adrenal metastatic lesions[16]. According to the AACE/AAES (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons) guidelines, CT-guided FNA of an adrenal lesion can be performed to confirm metastatic disease if a definitive diagnosis is needed for oncologic treatment planning[16].

In our series, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of adrenal gland EUS-FNA for the diagnosis of malignancy was of 86%, 97%, 96% and 89%, respectively. These results are similar to other series which report adrenal gland EUS-FNA sensitivity and negative predictive value rates ranging from 86%-100% and 70%-100%, respectively yet most of these studies have only included patients with underlying lung cancer [6,13].

With the widespread availability of CT and therefore percutaneous CT-guided fine-needle aspiration of the adrenals, the use of EUS-FNA to obtain adrenal gland biopsy could be questioned. While percutaneous CT-guided adrenal gland EUS-FNA of lesions of 2.8-5 cm in size, has been reported to be reliable and predict a benign course on long term follow up in patients with a benign cytology result[17], the reported rate of complications from percutaneous CT-guided adrenal gland EUS-FNA ranges from 0%-12% with an overall rate of 5.3%[7,15]. The most frequent adverse events related to percutaneous adrenal biopsies include hemorrhage and pneumothorax. Less common adverse events are pain, pancreatitis, and rarely needle-tract seeding. In our study we identified no short term (< 48 h) adverse events in any patient and no adverse events in those with available long term follow-up. In the current series, we performed diagnostic left adrenal biopsies in 2 of 3 patients in whom percutaneous approach of the left adrenal gland had been previously attempted unsuccessfully. These findings have been reported by others and emphasize that EUS-FNA may be utilized as a rescue procedure for those in whom percutaneous biopsies are contraindicated or unsuccessful[9]. Taken together, EUS-FNA appears to be a safe procedure and an acceptable alternative to percutaneous sampling of the adrenal glands.

About 5% of all incidentally discovered adrenal lesions are pheochromocytomas, and 25% of all pheochromocytomas are discovered incidentally. Typical features of pheochromocytomas include paroxysmal hypertension, headaches, sweating and palpitations; but, patients may not present with classical symptoms and up to 8% may be asymptomatic[18]. Sood et al[18] reported 3 cases of patients with catecholamine secreting tumors who underwent CT-guided percutaneous mass biopsy, including one with a pheochromocytoma and did not experience any adverse events related to the biopsy. In our series, one patient was unexpectedly diagnosed with pheochromocytoma by EUS-FNA and did not experience any adverse events from the procedure.

EUS shows a normal or minimally enlarged left adrenal gland in 98% of patients compared with only a 69% by transabdominal ultrasound[19]. A normal or minimally enlarged right adrenal gland, however, is seen in only 30% of patients on EUS, whereas transabdominal ultrasound permits detection in nearly all patients. Therefore, left adrenal EUS-FNA is attempted more often than right adrenal biopsies[19]. Recently, Uemura reported a rate of visualization of the right adrenal gland of 87.3% (n = 150) on EUS[13]. To date, there have been only a few reports of successful right adrenal gland EUS-FNA, but no large case-series[9-12,20]. The utility of EUS-FNA of right adrenal masses requires further clarification.

In our case series, the median adrenal gland diameter was higher in patients with diagnostic benign biopsies compared to malignant FNA specimens. This is in contrast with the results reported by Eloubeidi et al[12] who found larger masses in patients with malignancy (3.1 cm) compared to those with benign lesions (2.3 cm). A potential reason for this difference is that our group has aggressively biopsied adrenal masses over 3 cm in size in the following patients: (1) a history of malignancy; (2) a new diagnosis of cancer; or (3) a suspected recurrence due to the significant impact a diagnosis of metastatic malignancy has in this population.

Various techniques have been used to estimate the probability of malignancy of an adrenal mass, including its size, imaging characteristics and growth rate on serial imaging[16]. Asymptomatic patients with an indeterminate initial imaging study are advised to have follow-up imaging in 3-12 mo to assess for growth[16]. Surgical resection is recommended for lesions that grow; however, the threshold increase in size and growth rate that triggers resection have not been determined[16]. Guidelines from the AACE/AAES in 2009 on the management of adrenal incidentalomas recommend that benign appearing lesions smaller than 4 cm should have repeat adrenal imaging at 3-6 mo and then annually for 1-2 years. These same guidelines recommend surgery for growth rate more than 1cm or development of a hormonally active lesion (grade 3, Level C evidence)[16]. Based on these recommendations above, we utilized adrenal growth rate of ≤ 1 cm at follow imaging 6 mo or longer after EUS to correct confirm benign cytology as a benign lesion.

Other studies evaluating adrenal gland EUS-FNA and its clinical impact in patients with established or suspected malignancy, have either used survival at ≥ 2 years as confirmation for benignancy or not reported follow-up for benign lesions[4,12,21]. Schuurbiers et al[17] reported follow-up imaging for 10/30 patients with either benign or non-diagnostic EUS-FNA of the left adrenal gland. Similarly, Uemura et al[13] reported follow-up imaging at 6 mo for 4/7 patients with benign EUS-FNA and underlying lung cancer. To our knowledge, our series represents the first large study to utilize growth rates to confirm benign adrenal lesions and utilize these data to calculate test characteristics of EUS-FNA in non-cancer patients undergoing right and/or left adrenal gland EUS-FNA (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of different Studies evaluating adrenal gland endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration

| Ref. | Year | Number of patients | Patient population | EUS-FNA Left adrenal, n | Patient population | EUS-FNA Left adrenal, n | EUS-FNA Right adrenal, n | Benign EUS-FNA cytology, n | Malignant EUS-FNA cytology (n) | Non-Diagnostic rate | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | F/U for benign lesions | Method for F/U |

| Current research | 2014 | 94 | Patients undergoing EUS-FNA of either adrenal | 94 | Patients undergoing EUS-FNA of either adrenal | 90 | 5 | 60 | 25 | 10% | 86% | 97% | 96% | 89% | Available on 36/60 | CT/MRI, repeat EUS at ≥ 6 mo or surgical pathology from adrenalectomy |

| 1Uemura et al[13] | 2013 | 150 | Potentially resectable lung cancer | 150 | Potentially resectable lung cancer | 91 | 51 | 7 | 4 | 0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Available in 4/7 | F/U CT at 6 months |

| Schuurbiers et al[17] | 2011 | 85 | Lung cancer | 150 | Lung cancer | 85 | 0 | 25 | 55 | 6% | 86% | 96% | 91% | 70% | Available in 23/30 | Clinical (n = 11) or F/U CT (n = 10)2 |

| Eloubeidi et al[12] | 2010 | 59 | Known or suspected malignancy | 59 | Known or suspected malignancy | 54 | 5 | 37 | 22 | 0% | NR | NR | NR | NR | Clinical F/U for 37 | Not part of study protocol |

| Bodtger et al[4] | 2009 | 40 | Known or suspected lung cancer | 40 | Known or suspected lung cancer | 40 | 0 | 29 | 11 | 0% | 94% | 43% | 91% | 55% | Available | Survival at 2 yr |

EUS-FNA was done in 11 patients, 3 had bilateral EUS-FNA;

Two patients had CT at 3 mo. EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; FNA: Fine-needle aspiration; F/U: Follow up; N/A: Not available; NR: Not reported; CT: Computerized Tomography.

False positive results for malignancy have been reported with EUS-FNA and its incidence varies anywhere from 1% to 15%[22]. Our rate was 1% and it was considered to be secondary to cytological misinterpretation.

Potential limitations of this study include limited assessment of long-term adverse events after EUS-FNA due to inability to contact patients within weeks of the procedure. Nevertheless, a careful review of the available records was performed and all patients were contacted for short term events within 48 h of the procedure. Secondly, many patients with benign adrenal gland FNA cytology had underlying cancer and died before follow-up CT or never followed up, which could have affected the final diagnosis of the nature of the adrenal gland abnormality. However, because follow-up imaging was not available for these patients, they were excluded from the sensitivity analysis.

Another potential limitation is that during several years of the study time period, PET scan was not available and therefore is not applicable to this case series. With the advent of PET, any decision to pursue a biopsy for a positive or indeterminate PET scan is generally at the discretion of the referring physician. With widespread metastatic disease, a positive scan within either adrenal is likely considered as diagnostic for metastatic disease and therefore a biopsy would not be necessary. However, in a patient with known or suspected malignancy and a positive adrenal gland on PET in isolation, we advocate EUS-FNA of the adrenal as this may signify novel metastatic disease which may merit additional or novel chemotherapy or possibly adrenalectomy.

In conclusion, EUS-FNA of the adrenal is a safe, minimally invasive and sensitive technique with significant impact in the management of patients with malignancy diagnosed either prior or during the procedure. It permits surgical treatment for cancer in patients with localized malignancy and a benign adrenal lesion. This technique also diagnoses metastatic disease and cancer recurrence, avoiding unnecessary invasive surgical procedures in patients with established metastatic disease by adrenal biopsy.

COMMENTS

Background

Different modalities can be used to sample the adrenal glands. Image guided fine-needle aspiration using either CT and ultrasound guidance have traditionally been used. With the advent of new endoscopic techniques, endoscopic ultrasound guidance for fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of either adrenal gland has become a very plausible technique for this matter. There have been reports of adrenal gland EUS-FNA and this has shown to be a very safe and minimally invasive procedure.

Research frontiers

When sampling adrenal gland lesions, especially in patients with known or suspected underlying malignancy, it is of supreme importance not only the technique used possesses a great deal of diagnostic accuracy, but also to understand how did previous studies obtain that diagnostic accuracy; this relates to the method for follow up of lesions with benign cytology results. This is a very important area of research in this subject.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Most publications regarding EUS-FNA have universally included patients with underlying malignancy and, have had small patient numbers and/or have not included repeat imaging to document follow up on lesions with benign cytology results. According to the recommendations of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, adrenal lesions with benign appearance and smaller than 4cm, should have repeat adrenal imaging at 3-6 mo. These same guidelines also recommend surgery if the growth rate exceeds 1cm or if the lesion becomes hormonally active. In our study, we included 94 patients that had EUS-FNA of either adrenal gland, reviewed records and, abstracted information about EUS indication, EUS findings, EUS-FNA results, clinical and follow up imaging if this was available. A true diagnosis of a benign lesion was considered when there was a benign EUS-FNA result and the lesion had not grown more than 1 cm from its original size on follow up CT/MRI or repeat EUS or if the patient underwent adrenalectomy when the surgical pathology was benign. The clinical impact of adrenal EUS-FNA was analyzed on a case by cases basis. In the present study, the authors showed that adrenal gland EUS-FNA is a sensitive, specific, and safe minimally invasive diagnostic technique that has a great impact in patient care. Adrenal gland EUS-FNA ruled out metastatic disease in patients with underlying malignancy, therefore permitting surgery for primary tumor; it also made the initial diagnosis of stage IV cancer or recurrent malignancy in others.

Applications

This study suggests that adrenal gland EUS-FNA is a clinically useful, accurate and a safe technique in patients with adrenal gland mass or enlargement regardless or the presence of underlying malignancy.

Terminology

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or echo-endoscopy is a procedure in which endoscopy is combined with ultrasound to obtain images of the internal anatomy. Combined with Doppler imaging, nearby blood vessels can be evaluated. During the performance of this procedure, abnormal structures can be biopsied using a fine-needle aspiration technique.

Peer review

This is a retrospective single-center case-series evaluating the impact of EUS-FNA (Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration) in the evaluation of patients with left and/or right adrenal gland lesions discovered at EUS as part of a staging procedure or incidentally for other indications. The authors should be congratulated in their effort to present real clinical impact of EUS-FNA in patients with both malignant and benign adrenal lesions/findings that has never been done before, where patient population were mainly patients with cancer who were undergoing EUS-FNA for staging purposes.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Braden B, Chen Z, Larghi A, Pompili M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Pantalone KM, Gopan T, Remer EM, Faiman C, Ioachimescu AG, Levin HS, Siperstein A, Berber E, Shepardson LB, Bravo EL, et al. Change in adrenal mass size as a predictor of a malignant tumor. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:577–587. doi: 10.4158/EP09351.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuruba R, Gallagher SF. Current management of adrenal tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:34–46. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f301fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeWitt J, Alsatie M, LeBlanc J, McHenry L, Sherman S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of left adrenal gland masses. Endoscopy. 2007;39:65–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodtger U, Vilmann P, Clementsen P, Galvis E, Bach K, Skov BG. Clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration of left adrenal masses in established or suspected lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1485–1489. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b9e848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma KV, Venkatesan AM, Swerdlow D, DaSilva D, Beck A, Jain N, Wood BJ. Image-guided adrenal and renal biopsy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;13:100–109. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harisinghani MG, Maher MM, Hahn PF, Gervais DA, Jhaveri K, Varghese J, Mueller PR. Predictive value of benign percutaneous adrenal biopsies in oncology patients. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:898–901. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumachi F, Borsato S, Brandes AA, Boccagni P, Tregnaghi A, Angelini F, Favia G. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of adrenal masses in noncancer patients: clinicoradiologic and histologic correlations in functioning and nonfunctioning tumors. Cancer. 2001;93:323–329. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arellano RS, Garcia RG, Gervais DA, Mueller PR. Percutaneous CT-guided radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: efficacy of organ displacement by injection of 5% dextrose in water into the retroperitoneum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1686–1690. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eloubeidi MA, Beydoun M, Jurdi N, Husari A. Transduodenal EUS-guided FNA of the right adrenal gland to diagnose lung cancer where percutaneous approach was not possible. J Med Liban. 2011;59:173–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Varadarajulu S. Diagnosis of bilateral adrenal metastases secondary to malignant melanoma by EUS-guided FNA. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1862–1863. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeWitt JM. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of right adrenal masses: report of 2 cases. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:261–267. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eloubeidi MA, Black KR, Tamhane A, Eltoum IA, Bryant A, Cerfolio RJ. A large single-center experience of EUS-guided FNA of the left and right adrenal glands: diagnostic utility and impact on patient management. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:745–753. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uemura S, Yasuda I, Kato T, Doi S, Kawaguchi J, Yamauchi T, Kaneko Y, Ohnishi R, Suzuki T, Yasuda S, et al. Preoperative routine evaluation of bilateral adrenal glands by endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration in patients with potentially resectable lung cancer. Endoscopy. 2013;45:195–201. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu HH, Cramer HM, Kho J, Elsheikh TM. Fine needle aspiration cytology of benign adrenal cortical nodules. A comparison of cytologic findings with those of primary and metastatic adrenal malignancies. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1352–1358. doi: 10.1159/000332167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsitouridis I, Michaelides M, Stratilati S, Sidiropoulos D, Bintoudi A, Rodokalakis G. CT guided percutaneous adrenal biopsy for lesions with equivocal findings in chemical shift MR imaging. Hippokratia. 2008;12:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Duh QY, Hamrahian AH, Angelos P, Elaraj D, Fishman E, Kharlip J. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15 Suppl 1:1–20. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.S1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuurbiers OC, Tournoy KG, Schoppers HJ, Dijkman BG, Timmers HJ, de Geus-Oei LF, Grefte JM, Rabe KF, Dekhuijzen PN, van der Heijden HF, et al. EUS-FNA for the detection of left adrenal metastasis in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;73:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood SK, Balasubramanian SP, Harrison BJ. Percutaneous biopsy of adrenal and extra-adrenal retroperitoneal lesions: beware of catecholamine secreting tumours! Surgeon. 2007;5:279–281. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich CF, Wehrmann T, Hoffmann C, Herrmann G, Caspary WF, Seifert H. Detection of the adrenal glands by endoscopic or transabdominal ultrasound. Endoscopy. 1997;29:859–864. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma R, Ou S, Ullah A, Kaul V. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the right adrenal gland. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E385–E386. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ang TL, Chua TS, Fock KM, Tee AK, Teo EK, Mancer K. EUS-FNA of the left adrenal gland is safe and useful. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleeson FC, Kipp BR, Caudill JL, Clain JE, Clayton AC, Halling KC, Henry MR, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Wang KK, et al. False positive endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration cytology: incidence and risk factors. Gut. 2010;59:586–593. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.187765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]