Abstract

Background:

Because of more frequency of suicidal attempts in females, we need to study about its relationship with the female hormones. The aim of this study was to evaluate the serum estrogen and progesterone concentration and their relationship with suicidal attempt ranking in the attempted females.

Materials and Methods:

The studied cases chose from patients who had referred to clinical toxicology emergency of Noor Hospital (Isfahan, Iran), during 2012, because of suicidal attempt. The estrogen and progesterone serum level of the 111 females were measured during 24 hours after suicidal attempt. The rank of their suicide, the demographic properties, and the menstrual cycle phase of them were also registered, as the patient's statement. The results were analyzed by ANCOVA and Kruscal-Wallis under SPSS16.

Results:

Mean serum concentration of the estrogen was 76.8 pg/mL, and the mean serum concentration of progesterone was 2.99 ng/mL. Of them, 62.2% were in the luteal phase, and 37.8% were in the follicular phase, as they said. The serum progesterone concentration of the patients with more than two times suicidal attempts was significantly higher than the others.

Conclusion:

The suicidal attempt ranks significantly related to the serum progesterone concentration and the luteal phase.

Keywords: Estrogen, progesterone, suicidal attempt

INTRODUCTION

More than 1000 of people die every day because of suicide, and about ten times attempt suicide, worldwide.[1] Suicide attempts are more common in females. Suicide is a sign of psychiatric disorder in which different psychological, biological, social, and economic factors may play role in predisposing it. Considering more suicidal attempts in females, recently researchers have noted about the probable relationship between the suicidal attempts and the hormonal factors, especially female hormones.[2,3,4]

Studies about the relation between the suicidal attempt and menstrual cycles have different results, which can be divided in four categories: (1) no relationship between suicidal behaviors and the menstrual cycle;[5,6,7] (2) more frequency of suicidal attempts during the premenstrual phase;[8,9,10] and (3) more frequency of suicidal attempt during the menstrual bleeding phase,[11,12,13,14,15,16] and (4) the more frequency of suicidal attempts during the first and fourth weeks of menstrual cycles.[17,18] Most of these studies used the interview technique for assessing the menstrual cycle phase,[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] although few of them measured hormones, but even some of these assessed the hypothalamo-hypophyseal and adrenal hormones for their studies.[2,8] One may suppose that the menstrual cycle phase can be assessed accurately by postmortem endometrial histology, but even this cannot be without bias, because some of the suicides are reported as a nonsuicidal one.[13] Besides, the rank of the suicidal attempt was not an important variable in most of the past studies.

Considering the controversies of the results of the previous studies about the relationship between the suicidal attempt and menstrual cycle, and the scarcity of objective studies which directly have appraised the hormonal levels of patients, we have measured the estrogen and progesterone levels of the female patients who have attempted suicide. We also evaluated the relationship between these hormones and the rank of suicidal attempt.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive analytic study has been performed on females, who have attempted suicide and were referred to the of the central province toxicology emergency of Isfahan Province, of the Noor Hospital (Isfahan, Iran) during 2012. The ethics committee of the Behavioral Sciences Research Center (BSRC) of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) approved the study ethics issues, and the informed consent was signed by patients or their caregivers. The inclusion criteria were suicide attempt in recent 24 hours and ages of 15-49 years old (y/o). The exclusion criteria were menopause, irregular menstrual cycle, using contraceptives during the last month, and disorientation about the menstrual cycle day. The sampling method was a convenience one. The demographic properties and the rank of suicidal attempt of patients were registered. A blood sample was obtained from the patients during 24 hours after the suicidal attempt and their serum estrogen and progesterone levels measured by the immunoassay method in a specific laboratory by a given technician. The data were analyzed by ANCOVA (for studying the relationship between the hormonal levels and the suicidal attempt ranks and the demographic properties) and the Kruskal-Wallis (for studying the relationship between the estrogen and progesterone levels and the suicidal attempt ranks) under SPSS16.

RESULTS

A total of 136 patients were enrolled in the study, but 25 of them were excluded; 2 patients because of menopause, 12 because of menstrual cycle irregularity, 4 because of using contraceptives, 4 because of disorientation about the menstrual cycle days, and 3 patients because of nonconsent to enter the study. Eventually, 111 persons were studied. The patient ages were 15-48 years (M ± SD = 25 ± 7), 48.6% were single (i.e. 54 patients), 48.6% were married (54 patients), and 2.7% were divorced (3 patients). Their educational status was no one illiterate, 9.9% of them were at the primary school level (11 patients), 16.2% at the guidance level (18 patients), 44.1% at the high school level (49 patients), 4.5% at the associate of arts (5 patients), 8.1% college students (9 patients), and 17.1% bachelor's degree (19 patients). Their career were 18% unemployed (20 patients), 28.8% home workers (32 patients), and 16.2% were member of staff (18 patients), 12.6% independent careers (14 patients), 8.1% college students (9 patients), and 16.2% were students (18 patients). Of them, 18.9% had psychiatric history (21 patients).

Of the total patients, 62.2% were single attempter (69 patients), 37.8% were recurrent attempters (49 patients). Of them, 62.2% mentioned their menstrual cycle as at the luteal phase, 27.2% at the second-half of the follicular phase, and 10.8% at the first-half of the follicular phase.

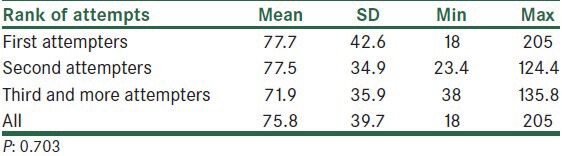

The mean estrogen level was 75.8 pg/mL, and the mean progesterone level was 2.99 ng/mL. Table 1 shows the relationships of the estrogen concentration with the suicidal attempt rankings. Kruskal-Wallis did not show any significant relationship between the estrogen level and the suicidal attempt rankings, but this relation was significant for the progesterone level; that is, in patients with three and more suicidal attempts the progesterone level was significantly higher [Table 2]. The ANCOVA shows similar conclusion, while using the suicidal ranks as an independent variance and the age year as a covariate one (P = 0.7 for estrogen levels, and 0.02 for progesterone).

Table 1.

Serum estrogen concentration (pg/mL) of suicidal attempters in accordance to suicide attempt ranks

Table 2.

Serum progesterone concentration (ng/mL) of suicidal attempters in accordance to suicide attempt ranks

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between estrogen and progesterone of attempted suicide females and their relationship with suicidal attempt rankings, regardless of their medical or psychiatric disorders. The results showed the serum progesterone level was 2.99 ± 3.16 ng/mL and the estrogen level was 7.58 ± 39.7 pg/mL, and there was a significant relationship between the progesterone level and the suicidal attempt history, i.e. the patients with three and more suicidal attempts have higher progesterone serum concentration (P = 0.02) [Table 2]. In contrast, most of the patients reported the luteal phase as the current menstrual cycle situation. The previous study,[21] which was based on the patient's statements about their menstrual days, and also, the Targum results,[7] Forest study,[10] and the Tanks study showed that most female suicidal patients attempt during the luteal phase.

CONCLUSION

These findings can guide us to some conclusions. First, the relationship between the female suicidal attempt and the feminine hormones is a reality and cannot be renunciated, as in some previous studies have been noted. Second, lower levels of estrogen may make patients susceptible to suicidal attempt, as this study data show more suicidal attempts in patients with lower levels of estrogen [Table 1]. Third, higher levels of the progesterone produce a condition similar to estrogen withdrawal, even if this condition occurred in the presence of higher estrogen levels. This high progesterone condition may weaken the action of the estrogen receptors.[22] No significant difference between the estrogen levels in patients with recurrent suicidal attempts may be due to this estrogen withdrawal-like conditions. These findings may somehow guide us to the cause of the controversies between the past studies.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

LIMITATIONS

This study, like every study, had some limitations. Focusing the sampling on mere the suicidal attempters via the self-toxication is one of these limitations. Although in our society most of the suicidal attempts do by self-poisoning. We did not calculate the progesterone-to-estrogen ratio in each patient, which may be another limitation. The third one was the renunciation of the patient's psychiatric diagnosis of the current disorder (s), but we focused on the suicidal attempt as a symptom because of its importance.

The future studies can evaluate our data reliability by analyzing the effect of the different methods of suicidal attempts and the different diagnoses on the relationship between the female hormones and the suicidal attempt ranks.

Briefly, the results of this study showed that the suicidal attempts ranks are significantly related to the higher level states of serum progesterone. This fact guides us to more cautious care of patients in the luteal phase.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Behavioral Sciences Research Center of the IUMS, Isfahan, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pallis DJ, Holding TA. The menstrual cycle and suicidal intent. J Biosoc Sci. 1976;8:27–33. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000010427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorga TD, Anderson AA, Kareday F. Menstrual cycle and suicide. Psycho Rep. 2007;707:430–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeis M, Shan P, Powl J. Incidence des period et syndrome pre ouperimenstrual study compartment suicide. Ann Med Psycho. 1997;145:429–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baca-García E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, Diaz FJ, de Leon J. Association between the menses and suicide attempts: A replication study. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:237–44. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000058375.50240.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sein AJ, Chodorowski Z, Ciechanowicz R, Wisniewski M, Pankiewicz P. The relationship between suicidal attempts and menstrual cycle in women. Przegl Lek. 2005;62:431–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zayas LH. A Retrospective on “The Suicidal Fit” in Mainland Puerto Ricans: Research Issues. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1989;11:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Targum SD, Caputo KP, Ball SK. Menstrual cycle phase and psychiatric admissions. J Affect Disord. 1991;22:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baca-García E, Díaz-Sastre C, de Leon J, Saiz-Ruiz J. The relationship between menstrual cycle phases and suicide attempts. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:50–60. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedmann E, Katcher AH, Brightman VJ. A prospective study of the distribution of illness within the menstrual cycle. Motiv Emot. 1978;2:355–68. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fourestié V, de Lignières B, Roudot-Thoraval F, Fulli-Lemaire I, Cremniter D, Nahoul K, et al. Suicide attempt in hypo strojenic phases of menstrual cycle. Lancet. 1996;2:1357–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass GS, Heninger GR, Lansky M, Talan K. Psychiatric emergency related to the menstrual cycle. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128:705–11. doi: 10.1176/ajp.128.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonks CM, Rose MJ. Attempted suicide and menstrual cycle. J Psychosome Res. 1998;11:319–23. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(68)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseny WS. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 2001. Handbook of cultural psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvard S. Psychiatric emergences. In: Sadock B, Sadock V, editors. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fourestie V, de LB, Roudot-Thoraval F, Fulli-Lemaire I, Cremniter D, Nahoul K, et al. Suicide attempts in hypo-oestrogenic phases of the menstrual cycle. Lancet. 1986;2:1357–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, García Resa E, Oquendo MA, Saiz-Ruiz J, et al. Premenstrual symptoms and luteal suicide attempts. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:326–9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caykoylu A, Capoglu I, Ozturk I. The possible factors affecting suicide attempts in the different phases of the menstrual cycle. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:460–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baca G, Sanchez A, Gonzalez D. Menstrual cycle and profile of suicidal behavior. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:33–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luggin R, Tal B, Peterson B. Acute psychiatry admission related to the menstrual cycle. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;69:461–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekeberg O, Jacobsen D. Self-poisoning and the menstrual cycle. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;73:239–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb02680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mousavi SGh, Koocheky A, Bateni V, Mardanian M. The relationship of suicide attempt and different phases of menstrual cycle in women referred to Isfahan Emergency Poisoning Center. J Res Behav Sci. 2008;1:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Reiz P. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Kapaln and Sadocks Comprehensive text book of psychiatry. [Google Scholar]