Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most important reasons of death. Hence, trials to prevent or lessen the complications originated by stroke are a goal of public health worldwide. The ischemia-reperfusion causes hypoxia, hypoglycemia and incomplete repel of metabolic waste products and leads to accumulation of free radicals triggering neuronal death. The A1 adenosine receptoras an endogenous ligand of adenosine is known to improve cell resistance to destructive agentsby preventing apoptosis. Vitamin C as a cellular antioxidant is also known as an effective factor to reduce damages initiated by free radicals. We studied the protective effects of A1 receptor agonist in combination with vitamin C against ischemia-reperfusion.

Methods

Ischemia was induced by common carotid artery occlusion in bulb-c mice (20-30 gr). Y-Maze was employed to scale the short-term memory and Nissl staining was used to count the cells in hippocampus.

Results

We found that concurrent treatment of A1 receptor agonist and vitamin C significantly reduced neuronal death in CA1. The Memory scores were also significantly improved (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our data point to the therapeutic effects of CPA/vitamin C co-administration and highlight the beneficial role of A1 adenosine receptor signaling in the context of stroke.

Keywords: Ischemia-Reperfusion, Hippocampus, A1 receptor, Vitamin C

1. Introduction

Cerebral ischemia, after heart attack and cancer, is the third cause of mortality and disability in people older than65 years in the world with no satisfactory cure (Camarata, Heros, & Latchaw, 1994; Organization, 2004).

Hippocampus which is known to be involved in memory formation and spatial information processing, is among the first areas of the brain affected by degenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and Parkinson's diseases and injuries caused by trauma and ischemia Hippocampus is very sensitive to hypoxia and free radicals formed during ischemic conditions. During ischemia reperfusion, released oxygen free radicals cause severe damage to cells. Rapid medical interventions may reduce ischemic necrosis and apoptosis (Bast, Haenen, & Doelman, 1991; Parman, Wiley, & Wells, 1999).

It has already found that the model of global cerebral ischemia leads to neurodegenerative lesions inCA1 area of hippocampus, stratum and the neocortex. It is also known that global cerebral ischemia can cause neuronal death in CA1 pyramidal hippocampus and reduces the spatial learning and memory in rats (McBean & Kelly, 1998).

Antioxidants are substances that remove free radicals, prevent damage to cell membranes and DNA, and reduce cell death. The usage of antioxidants has been recommended to prevent free radicals damaging the cells especially to lessen the destructive effects of ischemia. Vitamin C is a powerful antioxidant that is accessible in a proper diet (Iwata, Okazaki, Kamiuchi, & Hibino, 2010; Miura et al., 2009; Sato & Hall, 1992). Neuroprotective role of vitamin C as a powerful and available antioxidant was verified in several animal models (Iwata, et al., 2010).

A1 receptor, a member of purinergic receptors family, is distributed widely throughout the body including CA1 region (Deckert & Jorgensen, 1988). One of the important functions of this receptor is enhancing cell resistance to various environmental stresses preventing the process of programmed cell death, apoptosis (Becker et al., 2004; Drury & Szent-Györgyi, 1929; Hatfield, Belikoff, Lukashev, Sitkovsky, & Ohta, 2009; Kulinsky, Minakina, & Usov, 2001; Londos, Cooper, & Wolff, 1980). It has been approved that the accumulation of A1 receptors in the hippocampus (CA1) is correlated to neuroprotection against brain degenerative disease (Dirnagl, Iadecola, & Moskowitz, 1999; Velazquez, Frantseva, & Carlen, 1997).

Due to less information on administration of A1 receptor agonist, N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA) in combination with vitamin C on hypoxia complications, we designed this study to evaluate the effects of co-administration of vitamin C and CPA on ischemia-reperfusion induced cell death in hippocampus.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Fifty six adult bulb-c mice (20-30 gr) were obtained from Iranian Razzi Institute, Iran. Mice were maintained in Specific pathogen free unit at 21 ± 1C (50 ± 10% humidity) on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with access to water and food ad libitum.

2.2. Experimental Design

Mice were assigned to 8 experimental groups (n = 7/group) as follows:

1. Intact group: no ischemia, no treatment; 2. Ischemia control group: ischemia without any treatment; 3. Vehicle group: received treatment with vehicle from one week after ischemia to the end (second week after ischemia); 4. Pretreatment group: received vitamin C (100mg/kg) from one week before ischemia to the end; 5. A1 receptor agonist treatment: received CPA (1mg/ kg); 6. Combination treatment with vitamin C/CPA: received vitamin C (100mg/kg)/A1receptor agonist (1mg/ kg); 7. A1 receptor antagonist (DPCPX) treatment: received DPCPX (2.25mg/kg); 8. Combination treatment with vitamin C and DPCPX: received vitamin C (100mg/kg)/DPCPX (2.25mg/kg). Animals in groups 5 to 8 received their treatments from one week after ischemia to the end.

2.3. Ischemia Procedure

Animals in 2-8groups were subjected to 15 min of global brain ischemia induced by clamping the common carotid artery. Treatments were injected intraperitoneally after one week following reduction of inflammation in ischemic zone.

In order to evaluate the protective effects of vitamin C pretreatment, it was started one week prior to ischemia induction. The y-maze memory test performed two weeks following ischemia and then brains prepared for histological studies.

2.4. Y-maze Test

This working memory test is based on spontaneous exploration and alternations between arms with neither training nor food restriction (Lees, K.R., et al. 2006). Three identical arms are mounted symmetrically on an equilateral triangular center. In the test each mouse was placed at the end of one arm a permitted to walk through the maze for 300 second.

The ability to alternate requires that the animals know which arm they have already visited. In the task, each mouse was placed at the end of one arm and allowed to move through the maze for eight minutes. The percentage of alternation (defined as consecutive entries into all three arms without repetitions in overlapping triplet sets, to all possible alternations × 100%) was counted. For example, if the arms were marked as X, Y and Z and the animal entered the arms in the following order XYZXZYZXYXYZXZ, the actual alternation would be seven, and total number of arm entries would be fourteen and the percent alternation would be 58.33%.

2.5. Nissl Staining

This staining was used for identifying the basic neuronal structure from necrotic neurons in CA1 region.

Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (5/1) and perfused with cold PBS. Brains were removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 72 hours. Fixed tissues were paraffin-embedded and 5µm sections were prepared from each brain (from a minimum of three animals per group). Sections were then deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated through series of alcohol and rinsed in distilled water. Sections were then incubated with 0.1% cresyl violet solution for 3-10 minutes. Then slides were rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated in series of alcohol, cleared in xylene and finally mounted with permanent mounting medium and prepared for microscopy.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Comparisons of data were performed by one-way ANOVA. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

Co-administration of CPA and vitamin C inhibited short-term memory disruption

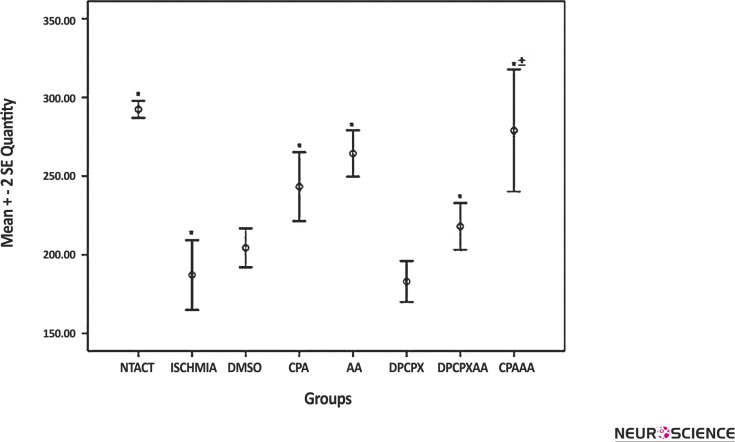

Y-maze behavioral test showed severe damage to short-term memory following ischemia with a significant difference compared to intact group(P < 0.05, Fig. 1). Treatment withCPA or vitamin C significantly reduced short-term memory disruption following ischemia compared to the ischemia group (P < 0.05, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of short term memory status among the experimental groups

Short term memory status was measured using Y maze. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Ischemic group represents significant difference compare to the intact group (*P < 0.05). Treatment groups, except DMSO and DPCPX treated groups represent significant difference compared to ischemic group (*P < 0.05). The group named CPA/AA treated with CPA and vitamin C showed a significant increase in Y-Maze results, compared to the CPA or vitamin C groups (±P < 0.05).

Co-adminisration of CPA and vitamin C significantly improved memory scores compared to single administration of CPA or vitamin C (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). DPCPX showed a decrease in short memory with no significant difference compared to the ischemia group (Fig. 1).

Co-administration of CPA and vitamin C reduced number of dead neurons in CA1 region

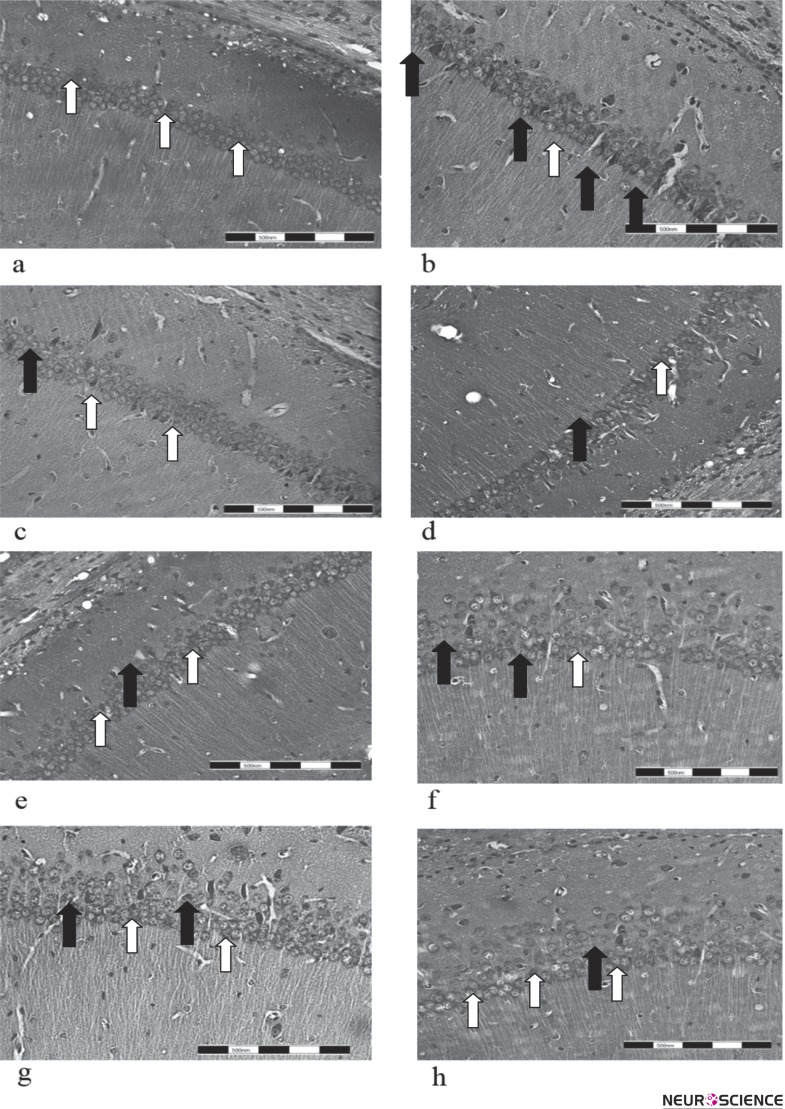

Cresyl violet (Nissl) staining showed the situation of normal and necrotic cells in tissue sections (Fig. 2). Ischemia reduced the density of normal cells in the CA1 area whereas animals treated with CPA or vitamin Chad less dead cells and a significant increased cell density (P < 0.05, Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Neuronal death in CA1 region of hippocampus

Cresyl violet staining of brain sections from experimental groups was performed at the end of treatment used to evaluate the neuronal density and structure. The Animals treated with CPA (f) or vitamin C (g) had more cell density which is representative of less dead neurons compared to the ischemia group (b). Co-administration of both CPA and vitamin C reduces cell death (h) compared to ischemia groups and groups received CPA (f) or vitamin C (g). Administration of A1 receptor antagonist (DPCPX) intensified the cell death among ischemic neurons and reduced cell density (d). White and black arrows are representative of normal and dead cells, respectively. Experimental groups including Intact, Ischemia, DMSO, DPCPX, DPCPX/AA, CPA, AA (vitamin C) and CPA/AA are shown a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h digital images prepared at 40 x magnifications, respectively. Scale bars: 200 µm.

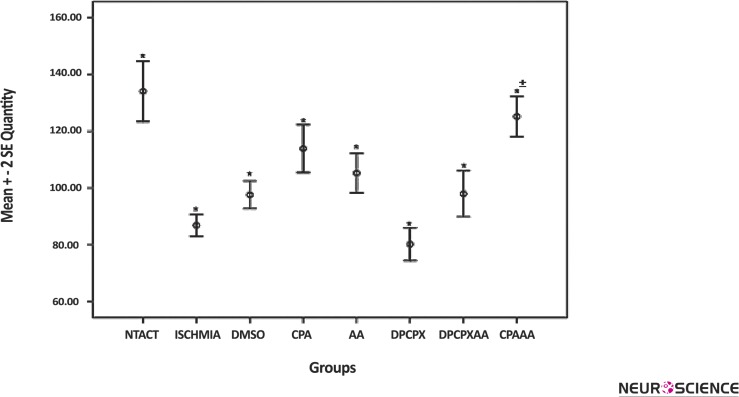

Figure 3.

Comparison of the normal cells density in the CA1 region of hippocampus

Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Cell density was measured by counting normal neurons in CA1 region using cresyl violet staining. Cell density in groups treated with CPA or vitamin C (shown with AA) is significantly increased compared to the ischemic group (*P < 0.05). The group named CPA/ AA, treated with both CPA and vitamin C showed a significant increase in density of normal cells in the CA1 region compared to the CPA or vitamin C (AA) groups (±P < 0.05).

Co-adminisration of CPA and vitamin C caused a significant decreased in number of dead neurons compared to single administration of CPA or vitamin C (P < 0.05, Fig. 3). DPCPX intensified cell death among ischemic neurons and reduced cell density significantly compared to the ischemia group (P < 0.05, Fig. 3)

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that co-administration of CPA and vitamin C can reduce destructive effects of ischemia reperfusion such as spatial memory loss and neuronal death. Less number of dead cells in CA1 region of hippocampus in CPA and vitamin C treatment group suggests neuroprotective effects for combination therapy against tissue destruction following ischemia.

Our study reveals the protective effects of CPA/Vitamin C co-administration for the first time. The results of this study showed that improvement of memory status in treatment groups has been closely correlated with the effects of therapeutic strategy on neuronal death. This study showed that vitamin C and CPA, as protective and/or therapeutic agents, can increase the survival of hipocampal neurons in the brain and thus improves hipocampal function by reducing damage to neurons caused by free radicals in stressful conditions. But also introduce CPA/vitamin C as a successful approach containing both vitamin C and CPA positive effects.

A previous study by Miura, 2009 demonstrated that treatment with vitamin C during hypoxia in newborn animals’ brain can reduces the number of both necrotic and apoptotic cells in cortex, caudate putamen, thalamus and hippocampus (Miura, et al., 2009). Their results showed that vitamin C is neuroprotective after hypoxic ischemia in immature rat brain.

Moreover, protective effects of CPA has been demonstrated on heart and cardiovascular system before by Urmaliya, with improved post-ischemic contractility, left ventricular developed pressure, end diastolic pressure and reduced infarct size (Urmaliya et al., 2010; Urmaliya, Pouton, Ledent, Short, & White, 2010). Other studies revealed that activation of adenosine receptors in neuronal membranes prevents the onset of enzymatic cascade responsible for neuronal apoptosis and gives them enough time to repair their structures and resume normal activities (Dirnagl, et al., 1999; Regan et al.,2003; Velazquez, et al., 1997). Thus using a combination of these two components as shown in our study can be more favorable than taking each medication alone. This can be due to the fact that vitamin C decrease neuronal vulnerability to ischemia and if it fails and neurons are damaged, adenosine A1 receptor agonist postpones the onset of apoptosis and gives them time to repair which results is reducing ischemic complications.

In conclusion, concurrent treatment with vitamin C and adenosine A1 Receptor agonist (CPA) can be tested as a pharmaceutical approach to lessen destructive effects of ischemia reperfusion on hippocampus.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank research council of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for financial support of the present study.

References

- Bast, A., Haenen, G. R. M. M., & Doelman, C. J. A. (1991). Oxidants and antioxidants: state of the art. The American journal of medicine, 91(3), S2–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, O. M., Marantz, Y., Shacham, S., Inbal, B., Heifetz, A., Kalid, O., et al. (2004). G protein-coupled receptors: in silico drug discovery in 3D. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(31), 11304–11309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarata, P. J., Heros, R. C., & Latchaw, R. E. (1994). “Brain Attack”: The Rationale for Treating Stroke as a Medical Emergency. Neurosurgery, 34(1), 144–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckert, J., & Jorgensen, M. B. (1988). Evidence for pre-and postsynaptic localization of adenosine A1 receptors in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain research, 446(1), 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl, U., Iadecola, C., & Moskowitz, M. A. (1999). Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends in neurosciences, 22(9), 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, A., & Szent-Györgyi, A. (1929). The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. The Journal of physiology, 68(3), 213–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, S., Belikoff, B., Lukashev, D., Sitkovsky, M., & Ohta, A. (2009). The antihypoxia-adenosinergic pathogenesis as a result of collateral damage by overactive immune cells. Journal of leukocyte biology, 86(3), 545–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, N., Okazaki, M., Kamiuchi, S., & Hibino, Y. (2010). Protective effects of oral administrated ascorbic acid against oxidative stress and neuronal damage after cerebral ischemia/ reperfusion in diabetic rats. Journal of Health Science, 56(1), 20–30 [Google Scholar]

- Kulinsky, V., Minakina, L., & Usov, L. (2001). Role of adenosine receptors in neuroprotective effect during global cerebral ischemia. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine, 131(5), 454–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees KR, Zivin JA, Ashwood T, Davalos A, Davis SM, Diener H-C, et al. , NXY-059 for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med, 2006. 354(6): p. 588–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londos, C., Cooper, D., & Wolff, J. (1980). Subclasses of external adenosine receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 77(5), 2551–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBean, D. E., & Kelly, P. A. T. (1998). Rodent models of global cerebral ischemia: a comparison of two-vessel occlusion and four-vessel occlusion. General Pharmacology: The Vascular System, 30(4), 431–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura, S., Ishida-Nakajima, W., Ishida, A., Kawamura, M., Ohmura, A., Oguma, R., et al. (2009). Ascorbic acid protects the newborn rat brain from hypoxic-ischemia. Brain and Development, 31(4), 307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. (2004). The World Health Report 2004: Changing History, Annex Table 3: Burden of disease in DALYs by cause, sex, and mortality stratum in WHO regions, estimates for 2002. Geneva: WHO [Google Scholar]

- Parman, T., Wiley, M. J., & Wells, P. G. (1999). Free radical-mediated oxidative DNA damage in the mechanism of thalidomide teratogenicity. Nature medicine, 5(5), 582–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan, S. E., Broad, M., Byford, A. M., Lankford, A. R., Cerniway, R. J., Mayo, M. W., et al. (2003). A1 adenosine receptor overexpression attenuates ischemia-reperfusion-induced apoptosis and caspase 3 activity. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 284(3), H859–H866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, P. H., & Hall, E. D. (1992). Tirilazad Mesylate Protects Vitamins C and E in Brain Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Journal of neurochemistry, 58(6), 2263–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urmaliya, V. B., Pouton, C. W., Devine, S. M., Haynes, J. M., Warfe, L., Scammells, P. J., et al. (2010). A novel highly selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist VCP28 reduces ischemia injury in a cardiac cell line and ischemia–reperfusion injury in isolated rat hearts at concentrations that do not affect heart rate. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology, 56(3), 282–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urmaliya, V. B., Pouton, C. W., Ledent, C., Short, J. L., & White, P. J. (2010). Cooperative cardioprotection through adenosine A1 and A2A receptor agonism in ischemia-reperfused isolated mouse heart. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology, 56(4), 379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez, J. L. P., Frantseva, M. V., & Carlen, P. L. (1997). In vitro ischemia promotes glutamate-mediated free radical generation and intracellular calcium accumulation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. The Journal of neuroscience, 17(23), 9085–9094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]