Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor initially identified because of its role in controlling the cellular response to environmental molecules. More recently, AHR has been shown to play a crucial role in controlling innate and adaptive immune responses through several mechanisms, one of which is the regulation of tryptophan metabolism. Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) are considered rate-limiting enzymes in the tryptophan catabolism and play important roles in the regulation of the immunity. Moreover, AHR and IDO/TDO are closely interconnected: AHR regulates IDO and TDO expression, and kynurenine produced by IDO/TDO is an AHR agonist. In this review, we propose to examine the relationship between AHR and IDO/TDO and its relevance for the regulation of the immune response in health and disease.

Keywords: aryl hydrocarbon receptor; 2,3-dioxygenase; tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase

AHR Signaling Pathways

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor belongs to the family of basic-helix–loop–helix/Per–Arnt–Sim transcription factors. It is abundantly expressed in numerous tissues, such as liver, lung, and placenta (1, 2). Interestingly, AHR is highly conserved through evolution (3), highlighting its importance across the animal kingdom. Originally, AHR was studied in the context of the biological response to environmental toxins such as 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). However, it was later found that AHR has an important role in the regulation of immune responses by small molecules provided by the diet, the commensal flora, and metabolism. In its inactive state, AHR resides in the cytosol as part of a complex that includes other proteins such as the 90 kDa heat shock protein (HSP90), the AHR-interacting protein, p23, and the c-SRC protein kinase (4–7). It is thought that HSP90 and p23 protect the receptor from proteolysis and maintain a conformation suitable for ligand binding (8).

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is activated by ligands binding the PAS-B domain (9), triggering a conformational change that results in the dissociation of AHR from the chaperone proteins and the exposure of its nuclear localization sequence (10). Ligand activation of AHR elicits genomic and non-genomic AHR-dependent signaling pathways. Genomic AHR signaling involves the interaction of AHR with other transcription factors and co-activators to directly regulate the transcription of target genes (7). After ligand activation, AHR translocates to the nucleus where it dimerizes with the AHR nuclear translocator (ARNT) (11) to form an active DNA-binding complex and control the expression of target genes containing xenobiotic response elements (XREs) in their regulatory regions (9). The AHR–ARNT complex can promote or inhibit the expression of its target genes. Moreover, ChIP-seq and microarray studies with different cell types and ligands (12–14) suggest that the AHR target genes in a specific cell are determined by the ligands, and also the identity and developmental stage of the target cells (15).

Non-genomic AHR signaling is more diverse and encompasses, for example, the release of c-SRC from its complex with AHR, resulting in the phosphorylation of c-SRC cellular targets (7). In addition, AHR can promote the degradation of specific target proteins such as estrogen and androgen receptors by the proteasome. This ability to trigger the degradation of specific proteins results from its E3 ligase activity, by which AHR selects proteins for ubiquitination by E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. The resulting ubiquitinated proteins are then recognized by the 26S proteasome and degraded (16–18). Indeed, following activation AHR itself is eventually exported out from the nucleus and degraded by the 26S proteasome pathway (19–21).

Structure–activity relationship studies showed that AHR’s ligand binding pocket is promiscuous and able to accommodate numerous hydrophobic planar compounds (22). From an historic point of view, AHR can be seen as an endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) receptor, as it is known that EDCs affect the endocrine system either directly by AHR-dependent changes in gene expression or indirectly via AHR cross-talk with endocrine signaling pathways (23). However, both endogenous and exogenous AHR ligands have been identified. Classical AHR ligands include synthetic aromatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (HAHs and PAHs) as well as natural ligands tetrapyrroles, flavonoids, tryptophan derivatives, and dietary carotinoids (24). Interestingly, some of the natural AHR ligands, such as resveratrol (25) and 7-ketocholestrol (26) can act as antagonists rather than agonists. Within the endogenous AHR ligands, tryptophan-derived metabolites have become one of the most interesting and utmost studied group (7). It should be noted that AHR activation in the absence of ligand binding has also been described. Although the relevance of this observation for vertebrates is not completely understood, the ligand-independent activation of AHR might play a physiological role in invertebrates (see below).

AHR Evolution

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor homologs have been identified in most major groups of animals, including the two main clades of protostome invertebrates as well as deuterostomes (27, 28) highlighting the biological importance of AHR throughout the animal kingdom. AHR homologs identified in invertebrates share similarities with their vertebrate counterparts, such as the interaction with ARNT to recognize XRE (29–31). However, invertebrate AHR homologs do not bind known AHR ligands like TCDD or β-naphthoflavone (29, 31). Indeed, it was recently reported that the metabolic response to xenobiotics in Caenorhabditis elegans is not controlled by AHR (32).

In C. elegans, the orthologs of AHR and ARNT are encoded by the AHR-related (ahr-1) and ahr-1 associated (aha-1) genes, respectively. AHR-1 and AHA have HSP90 binding properties comparable to those of their mammalian counterparts (31). AHR-1 shares 38% amino acid identity with the human AHR over the first 395 amino acids. Furthermore, AHR-1 contains a PAS domain with both PAS-A and PAS-B repeats as well as a bHLH domain where specific residues mediating the recognition of mammalian XREs are conserved (31). However, AHR-1 does not have a glutamine-rich transcriptional activation domain similar to the one present in mammals.

Notably, mutations in AHR-1 affect several aspects of neuronal development determining, for example, the fate of GABAergic neurons in the L1 larval stage, regulating both cell and axon migrations as well as specifying the fate of AVM light touch sensory neuron (33–35). In addition, AHR-1 is involved in social feeding (36), in which nematodes form groups on the border of the bacterial lawn (37).

Recent studies have also demonstrated a role for AHR-1 in regulating the synthesis of long-chain unsaturated fatty acids that eventually produce lipid signaling molecules (38). This finding is consistent with findings in mouse models, where ligand activation of AHR has been linked to alterations in gene expression of fatty acid metabolism (39, 40).

The homologs of mammalian AHR and ARNT are encoded by spineless and tango in Drosophila melanogaster (41, 42). In agreement with observations made in C. elegans, spineless does not bind TCDD or β-naphthoflavone (29). In addition, sequence alignments suggest that key residues required for the interaction of mammalian AHR with TCDD are not conserved in spineless (29, 41). Thus, although it is still possible that the localization and/or the activity of spineless are modified by unknown endogenous ligands, it appears that this protein does not bind classical AHR ligands functional in mammalian systems. Moreover, in certain cells spineless appears to be constitutively active (43). Spineless plays a role in several aspects of antenna and leg development (41, 44), photoreceptor cell differentiation (45), and in controlling the morphology of sensory neurons (46).

Not surprisingly, most of our knowledge on mammalian AHR comes from studies on human beings and mice. Key features characterizing mammalian AHR are (1) in contrast to other vertebrates (47) all studied mammalians have a single AHR gene and (2) AHR in mammals is not only involved in the toxic effects of environmental pollutants (48, 49), it also has important roles in development (50–53) and immune responses [reviewed in Ref. (7)]. Indeed, it has been hypothesized that the original function of the AHR might have been developmental regulation and that AHR’s ability to bind HAHs, PAHs, and mediate adaptive responses involving induction of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes is a vertebrate innovation (3, 47).

Kynurenine Pathways TDO/IDO and Immune Regulation

Tryptophan metabolites have become one of the most interesting groups of endogenous AHR ligands. Especially kynurenine, an immediate tryptophan metabolite, has been extensively studied in recent years. The metabolic fate of tryptophan is conversion into a range of neuroactive substances, such as serotonin and melatonin. In addition, tryptophan can be catabolized into kynurenine metabolites. Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1), tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), and recently discovered IDO-related enzyme IDO2 (54) are the first and rate-limiting enzymes converting tryptophan to N-formylkynurenine (55, 56) which is then metabolized to l-kynurenine. Both TDO and IDO1 are thought to be intracellular enzymes (57, 58). Therefore, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (59), enzyme facilitating cellular entry of tryptophan, is considered to be another rate-limiting factor in tryptophan catabolism (60). l-Kynurenine can be catabolized by three different ways: (1) kynurenine monooxygenase, kynureninase, and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid oxidase catalyze the synthesis of anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, quinolinic acid, and 3-hydroxykynurenine. (2) Kynurenine aminotransfereases catalyze the synthesis of kynurenic acid. (3) Kynurenine monooxygenase and kynurenine aminotransfereases catalyze the synthesis of xanthurenic acid (Figure 1) [reviewed in Ref. (61)].

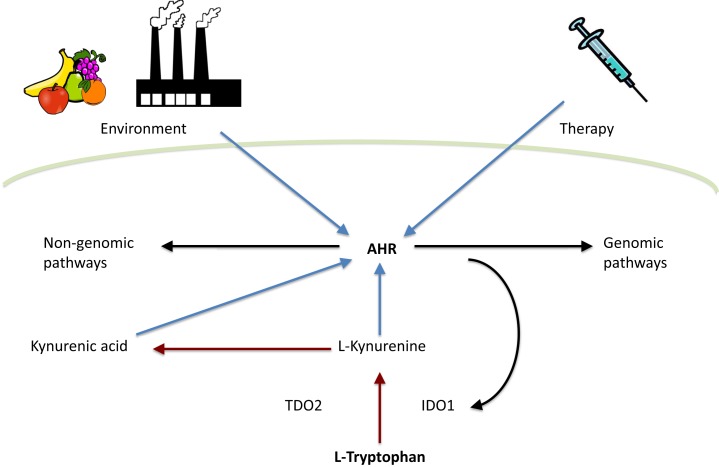

Figure 1.

Interplay between tryptophan metabolism and AHR. Tryptophan is metabolized by TDO2 and IDO1 to l-kynurenine, which is further converted to kynurenic acid. Both l-kynurenine and kynurenic acid can activate AHR. In addition, AHR activity is influenced by environment and therapy. Finally, AHR can activate either genomic or non-genomic AHR-dependent signaling pathways. Red arrows indicate tryptophan catabolism pathways, blue arrows indicate AHR activation, and black arrows indicate pathways activated by AHR.

In human beings, IDO1 is expressed in various tissues and cell subsets following cytokine stimulation during infection, transplantation, pregnancy, autoimmunity, and neoplasia (62–64). IDO1 is constitutively expressed in many human tumors, creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment as a result of tryptophan depletion and the synthesis of immunosuppressive metabolites such as kynurenine (65, 66). Surprisingly, the expression of IDO1 is controlled by AHR (67) via an autocrine AHR-IL6-STAT3 signaling loop (68). In addition, tryptophan starvation caused by IDO1 activity, together with IDO1-dependent tryptophan catabolism, inhibits the proliferation and activation of antigen-specific T lymphocytes and induces immune tolerance (69–72). In addition, strong evidence suggests that tryptophan catabolism can inhibit T-cell based adaptive immunity by inducing the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Treg) in tumors (62, 73–75). Interestingly, kynurenine is also indicated to promote the differentiation of Tregs (76) while suppressing antigen-specific T-cell responses (77).

In mammals, TDO2 is expressed primarily in the liver (78–80) but can also be detected in other tissues such as the brain (79, 81–83). TDO2 is constitutively expressed and activated in gliomas (84). Recently, lipopolysaccharide was demonstrated to induce TDO2 expression and via consequent production of kynurenine activate AHR-dependent pathways leading to protection against endotoxin challenge (85). In addition, this study also reported that endotoxin tolerance is also mediated by AHR as it was demonstrated that AHR activation by kynurenine elicits the c-SRC dependent phosphorylation of IDO1, which further regulates TGFβ1 production by dendritic cells as well as limits immunopathology triggered by both Salmonella typhimurium and group B Streptococcus (85). Furthermore, TDO2 derived kynurenine has been demonstrated to suppress antitumor immune responses as well as promote survival and motility of tumor cells via AHR in an autocrine manner (84). Note that kynurenic acid can also activate AHR signaling (86).

IDO/TDO Evolution

Unfortunately, not much is know about the kynurenine pathway in nematodes. However, the study of intestinal autofluorescence in relation to tryptophan catabolism revealed that nematodes having a mutated flu-1 gene show altered gut granule autofluoresence as well as decreased kynurenine hydroxylase activity (87). Whereas, flu-2 mutants have reduced kynureninase and gut granule autofluorescence (87). In support of these observations, the C. elegans genome has homologs of kynurenine hydroxylase and kynureninase in the vicinity of flu-1 and flu-2 loci (88).

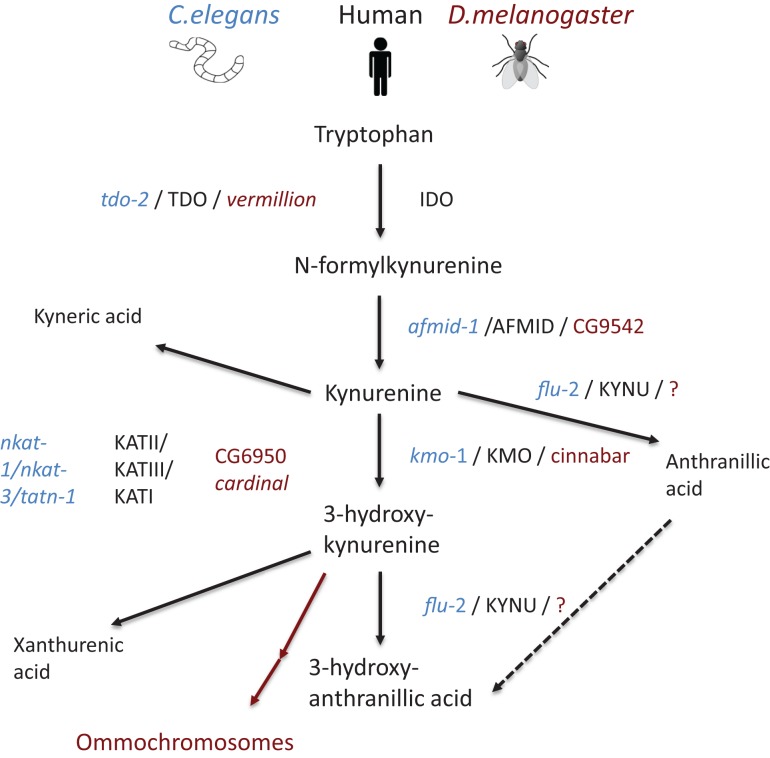

Additional putative kynurenine pathway related genes have been identified in the C. elegans genome (89) (Figure 2). The knock down of tdo-2, for example, abrogated the gut granule fluorescence (90, 91). Involvement of the C. elegans kynurenine pathway has been demonstrated in neurodegeneration and aging: in a C. elegans model of Parkinson’s disease; RNAi knock down of tdo-2 reduced α-synuclein aggregation-induced toxicity and increased life span (92). However, these effects were proven to be a result of increased tryptophan rather than changed levels of kynurenines (92).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the kynurenine pathway in human beings (mammal), C. elegans, and D. melanogaster. Pathway tree demonstrates differences between mammalian and invertebrate tryptophan catabolism. Mammalian enzymes are depicted in black, C. elegans enzymes in blue, and D. melanogaster in red. Modified from Ref. (89)

In D. melanogaster, tryptophan catabolism takes place in pigmented eyes (93–95). Remarkably, the role of kynurenine pathway in eye function is conserved from flies to mammals, as it plays an essential role in protecting the lens from ultraviolet irradiation (96). D. melanogaster TDO2 is encoded by vermillion. Flies having the vermillion mutation lack brown pigment in their eyes and have been thought to be deficient for TDO2 activity (93, 94, 97, 98). This was verified when kynurenine pathway and related genes were described in full in 2003 (99). In the same way, as in C. elegans, loss of vermillion function has been demonstrated to be neuroprotective in D. melanogaster model of Huntington’s disease (100). In addition, loss of vermillion function extend the life span of D. melanogaster (101, 102) while resulting gradual memory decline (103). Furthermore, white eye mutants having impaired ABC transport show extended life spans (102). In addition, other D. melanogaster mutants, cardinal and cinnabar, resulting in excess of 3-hydroxykynurenine and neuroprotective kynurenic acid, have been demonstrated to modify the brain plasticity (104).

Conclusion

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, a member of the dHLH-PAS superfamily, has been identified both in invertebrates and vertebrates, suggesting that the ancestral AHR gene arose over 500 million years ago (3). In vertebrates, especially in mammals, the activity of AHR is mostly regulated by its interactions with ligands. However, in invertebrates (e.g. C. elegans) AHR does not seem to interact with TCDD or any other known ligand (105), and it is constitutively localized in the nuclei of certain cells suggesting ligand-independent activation (34). Similar observations have been made for D. melanogaster’s spineless (29). Although one cannot rule out the possibility that invertebrates require a different kind of AHR ligands than vertebrates, it has been speculated that in early metazoans AHR might have had a ligand-independent roles in development. Thus, the ability of AHR to interact with ligands, bind HAHs and PAHs, and regulate xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes has been postulated to be a vertebrate novelty (3, 47).

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling modulates development and immune function in mammals (7). Fairly recently, the involvement of tryptophan metabolism has been implicated in regulating both innate and adaptive immune responses. Most importantly, kynurenine produced by TDO or IDO1 during tryptophan catabolism has been identified as an AHR ligand, linking IDO/TDO to AHR. Considering the evolutionary conservation of the kynurenine pathway, it is tempting to speculate that the cross-talk between AHR and IDO/TDO immunoregulatory pathways is a recent evolutionary innovation aimed at providing a mechanism to fine tune the immune response in response to environmental cues provided by the tissue microenvironment. This interpretation suggests that approaches targeting both AHR and IDO/TDO are likely to provide efficient new avenues for the therapeutic manipulation of the immune response.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project has been supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the National Institutes of Health, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, and the Finnish Multiple Sclerosis Foundation.

References

- 1.Dolwick KM, Schmidt JV, Carver LA, Swanson HI, Bradfield CA. Cloning and expression of a human Ah receptor cDNA. Mol Pharmacol (1993) 44:911–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolwick KM, Swanson HI, Bradfield CA. In vitro analysis of Ah receptor domains involved in ligand-activated DNA recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1993) 90:8566–70. 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn ME. Aryl hydrocarbon receptors: diversity and evolution. Chem Biol Interact (2002) 141:131–60. 10.1016/S0009-2797(02)00070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazlauskas A, Poellinger L, Pongratz I. Evidence that the co-chaperone p23 regulates ligand responsiveness of the dioxin (Aryl hydrocarbon) receptor. J Biol Chem (1999) 274:13519–24. 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Q, Whitlock JP, Jr. A novel cytoplasmic protein that interacts with the Ah receptor, contains tetratricopeptide repeat motifs, and augments the transcriptional response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Biol Chem (1997) 272:8878–84. 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perdew GH. Association of the Ah receptor with the 90-kDa heat shock protein. J Biol Chem (1988) 263:13802–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintana FJ, Sherr DH. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of adaptive immunity. Pharmacol Rev (2013) 65:1148–61. 10.1124/pr.113.007823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox MB, Miller CA, III. Cooperation of heat shock protein 90 and p23 in aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling. Cell Stress Chaperones (2004) 9:4–20. 10.1379/460.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukunaga BN, Probst MR, Reisz-Porszasz S, Hankinson O. Identification of functional domains of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Biol Chem (1995) 270:29270–8. 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikuta T, Kobayashi Y, Kawajiri K. Phosphorylation of nuclear localization signal inhibits the ligand-dependent nuclear import of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2004) 317:545–50. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyes H, Reisz-Porszasz S, Hankinson O. Identification of the Ah receptor nuclear translocator protein (Arnt) as a component of the DNA binding form of the Ah receptor. Science (1992) 256:1193–5. 10.1126/science.256.5060.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi J, Mori Y, Matsui S, Matsuda T. Comparison of gene expression patterns between 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and a natural arylhydrocarbon receptor ligand, indirubin. Toxicol Sci (2004) 80:161–9. 10.1093/toxsci/kfh129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao N, Lee KL, Furness SGB, Bosdotter C, Poellinger L, Whitelaw ML. Xenobiotics and loss of cell adhesion drive distinct transcriptional outcomes by aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling. Mol Pharmacol (2012) 82:1082–93. 10.1124/mol.112.078873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo R, Matthews J. High-resolution genome-wide mapping of AHR and ARNT binding sites by ChIP-Seq. Toxicol Sci (2012) 130:349–61. 10.1093/toxsci/kfs253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray IA, Morales JL, Flaveny CA, Dinatale BC, Chiaro C, Gowdahalli K, et al. Evidence for ligand-mediated selective modulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity. Mol Pharmacol (2010) 77:247–54. 10.1124/mol.109.061788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtake F, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S. AHR acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to modulate steroid receptor functions. Biochem Pharmacol (2009) 77:474–84. 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohtake F, Baba A, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S. Intrinsic AHR function underlies cross-talk of dioxins with sex hormone signalings. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2008) 370:541–6. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohtake F, Baba A, Takada I, Okada M, Iwasaki K, Miki H, et al. Dioxin receptor is a ligand-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase. Nature (2007) 446:562–6. 10.1038/nature05683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davarinos NA, Pollenz RS. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor imported into the nucleus following ligand binding is rapidly degraded via the cytosplasmic proteasome following nuclear export. J Biol Chem (1999) 274:28708–15. 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Q, Baldwin KT. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced degradation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Role of the transcription activaton and DNA binding of AHR. J Biol Chem (2000) 275:8432–8. 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollenz RS, Barbour ER. Analysis of the complex relationship between nuclear export and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol (2000) 20:6095–104. 10.1128/MCB.20.16.6095-6104.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waller CL, McKinney JD. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationships of dioxins and dioxin-like compounds: model validation and Ah receptor characterization. Chem Res Toxicol (1995) 8:847–58. 10.1021/tx00048a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson DB, Perdew GH. A dynamic role for the Ah receptor in cell signaling? Insights from a diverse group of Ah receptor interacting proteins. J Biochem Mol Toxicol (2002) 16:317–25. 10.1002/jbt.10051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denison MS, Nagy SR. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by structurally diverse exogenous and endogenous chemicals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol (2003) 43:309–34. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casper RF, Quesne M, Rogers IM, Shirota T, Jolivet A, Milgrom E, et al. Resveratrol has antagonist activity on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor: implications for prevention of dioxin toxicity. Mol Pharmacol (1999) 56:784–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savouret JF, Antenos M, Quesne M, Xu J, Milgrom E, Casper RF. 7-ketocholesterol is an endogenous modulator for the arylhydrocarbon receptor. J Biol Chem (2001) 276:3054–9. 10.1074/jbc.M005988200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson KJ, Butterfield NJ. Origin of the Eumetazoa: testing ecological predictions of molecular clocks against the Proterozoic fossil record. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2005) 102:9547–52. 10.1073/pnas.0503660102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson KJ, Lyons JB, Nowak KS, Takacs CM, Wargo MJ, McPeek MA. Estimating metazoan divergence times with a molecular clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2004) 101:6536–41. 10.1073/pnas.0401670101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler RA, Kelley ML, Powell WH, Hahn ME, Van Beneden RJ. An aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) homologue from the soft-shell clam, Mya arenaria: evidence that invertebrate AHR homologues lack 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and beta-naphthoflavone binding. Gene (2001) 278:223–34. 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00724-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emmons RB, Duncan D, Estes PA, Kiefel P, Mosher JT, Sonnenfeld M, et al. The spineless-aristapedia and tango bHLH-PAS proteins interact to control antennal and tarsal development in Drosophila. Development (1999) 126:3937–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell-Coffman JA, Bradfield CA, Wood WB. Caenorhabditis elegans orthologs of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its heterodimerization partner the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1998) 95:2844–9. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones LM, Rayson SJ, Flemming AJ, Urwin PE. Adaptive and specialised transcriptional responses to xenobiotic stress in Caenorhabditis elegans are regulated by nuclear hormone receptors. PLoS One (2013) 8:e69956. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang X, Powell-Coffman JA, Jin Y. The AHR-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its co-factor the AHA-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator specify GABAergic neuron cell fate in C. elegans. Development (2004) 131:819–28. 10.1242/dev.00959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin H, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans aryl hydrocarbon receptor, AHR-1, regulates neuronal development. Dev Biol (2004) 270:64–75. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith CJ, O’Brien T, Chatzigeorgiou M, Spencer WC, Feingold-Link E, Husson SJ, et al. Sensory neuron fates are distinguished by a transcriptional switch that regulates dendrite branch stabilization. Neuron (2013) 79:266–80. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin H, Zhai Z, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans AHR-1 transcription complex controls expression of soluble guanylate cyclase genes in the URX neurons and regulates aggregation behavior. Dev Biol (2006) 298:606–15. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Bono M, Bargmann CI. Natural variation in a neuropeptide Y receptor homolog modifies social behavior and food response in C. elegans. Cell (1998) 94:679–89. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81609-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aarnio V, Storvik M, Lehtonen M, Asikainen S, Reisner K, Callaway J, et al. Fatty acid composition and gene expression profiles are altered in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-1 mutant Caenorhabditis elegans. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol (2010) 151:318–24. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boverhof DR, Burgoon LD, Tashiro C, Chittim B, Harkema JR, Jump DB, et al. Temporal and dose-dependent hepatic gene expression patterns in mice provide new insights into TCDD-Mediated hepatotoxicity. Toxicol Sci (2005) 85:1048–63. 10.1093/toxsci/kfi162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato S, Shirakawa H, Tomita S, Ohsaki Y, Haketa K, Tooi O, et al. Low-dose dioxins alter gene expression related to cholesterol biosynthesis, lipogenesis, and glucose metabolism through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated pathway in mouse liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol (2008) 229:10–9. 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duncan DM, Burgess EA, Duncan I. Control of distal antennal identity and tarsal development in Drosophila by spineless-aristapedia, a homolog of the mammalian dioxin receptor. Genes Dev (1998) 12:1290–303. 10.1101/gad.12.9.1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonnenfeld M, Ward M, Nystrom G, Mosher J, Stahl S, Crews S. The Drosophila tango gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is orthologous to mammalian Arnt and controls CNS midline and tracheal development. Development (1997) 124:4571–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudo K, Takeuchi T, Murakami Y, Ebina M, Kikuchi H. Characterization of the region of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor required for ligand dependency of transactivation using chimeric receptor between Drosophila and Mus musculus. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1789:477–86. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Struhl G. Spineless-aristapedia: a homeotic gene that does not control the development of specific compartments in Drosophila. Genetics (1982) 102:737–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wernet MF, Mazzoni EO, Celik A, Duncan DM, Duncan I, Desplan C. Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature (2006) 440:174–80. 10.1038/nature04615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. The bHLH-PAS protein spineless is necessary for the diversification of dendrite morphology of Drosophila dendritic arborization neurons. Genes Dev (2006) 20:2806–19. 10.1101/gad.1459706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hahn ME, Karchner SI, Evans BR, Franks DG, Merson RR, Lapseritis JM. Unexpected diversity of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in non-mammalian vertebrates: insights from comparative genomics. J Exp Zoolog A Comp Exp Biol (2006) 305:693–706. 10.1002/jez.a.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez-Salguero PM, Hilbert DM, Rudikoff S, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice are resistant to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol (1996) 140:173–9. 10.1006/taap.1996.0210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mimura J, Yamashita K, Nakamura K, Morita M, Takagi TN, Nakao K, et al. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells (1997) 2:645–54. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1490345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benedict JC, Lin TM, Loeffler IK, Peterson RE, Flaws JA. Physiological role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mouse ovary development. Toxicol Sci (2000) 56:382–8. 10.1093/toxsci/56.2.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lahvis GP, Lindell SL, Thomas RS, McCuskey RS, Murphy C, Glover E, et al. Portosystemic shunting and persistent fetal vascular structures in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2000) 97:10442–7. 10.1073/pnas.190256997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robles R, Morita Y, Mann KK, Perez GI, Yang S, Matikainen T, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor of the PAS gene family, is required for normal ovarian germ cell dynamics in the mouse. Endocrinology (2000) 141:450–3. 10.1210/endo.141.1.7374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt JV, Su GH, Reddy JK, Simon MC, Bradfield CA. Characterization of a murine AHR null allele: involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1996) 93:6731–6. 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ball HJ, Sanchez-Perez A, Weiser S, Austin CJD, Astelbauer F, Miu J, et al. Characterization of an indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-like protein found in humans and mice. Gene (2007) 396:203–13. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu T, Nomiyama S, Hirata F, Hayaishi O. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Purification and some properties. J Biol Chem (1978) 253:4700–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takikawa O, Kuroiwa T, Yamazaki F, Kido R. Mechanism of interferon-gamma action. Characterization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in cultured human cells induced by interferon-gamma and evaluation of the enzyme-mediated tryptophan degradation in its anticellular activity. J Biol Chem (1988) 263:2041–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Tryptophan degradation by human placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase regulates lymphocyte proliferation. J Physiol (2001) 535:207–15. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00207.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfefferkorn ER, Rebhun S, Eckel M. Characterization of an indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase induced by gamma-interferon in cultured human fibroblasts. J Interferon Res (1986) 6:267–79. 10.1089/jir.1986.6.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mackenzie SM, Brooker MR, Gill TR, Cox GB, Howells AJ, Ewart GD. Mutations in the white gene of Drosophila melanogaster affecting ABC transporters that determine eye colouration. Biochim Biophys Acta (1999) 1419:173–85. 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00064-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan DT, Bell LA, Paton DR, Sullivan MC. Genetic and functional analysis of tryptophan transport in Malpighian tubules of Drosophila. Biochem Genet (1980) 18:1109–30. 10.1007/BF00484342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell BM, Charych E, Lee AW, Möller T. Kynurenines in CNS disease: regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Front Neurosci (2014) 8:12. 10.3389/fnins.2014.00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Curti A, Trabanelli S, Salvestrini V, Baccarani M, Lemoli RM. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the induction of immune tolerance: focus on hematology. Blood (2009) 113:2394–401. 10.1182/blood-2008-07-144485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu X, Liu Y, Ding M, Wang X. Reduced expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase participates in pathogenesis of preeclampsia via regulatory T cells. Mol Med Rep (2011) 4:53–8. 10.3892/mmr.2010.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maby-El Hajjami H, Amé-Thomas P, Pangault C, Tribut O, DeVos J, Jean R, et al. Functional alteration of the lymphoma stromal cell niche by the cytokine context: role of indoleamine-2,3 dioxygenase. Cancer Res (2009) 69:3228–37. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest (2007) 117:1147–54. 10.1172/JCI31178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Platten M, Wick W, Van den Eynde BJ. Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res (2012) 72:5435–40. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vogel CFA, Goth SR, Dong B, Pessah IN, Matsumura F. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling mediates expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2008) 375:331–5. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Litzenburger UM, Opitz CA, Sahm F, Rauschenbach KJ, Trump S, Winter M, et al. Constitutive IDO expression in human cancer is sustained by an autocrine signaling loop involving IL-6, STAT3 and the AHR. Oncotarget (2014) 5:1038–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frumento G, Rotondo R, Tonetti M, Damonte G, Benatti U, Ferrara GB. Tryptophan-derived catabolites are responsible for inhibition of T and natural killer cell proliferation induced by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Exp Med (2002) 196:459–68. 10.1084/jem.20020121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grohmann U, Fallarino F, Puccetti P. Tolerance, DCs and tryptophan: much ado about IDO. Trends Immunol (2003) 24:242–8. 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00072-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mellor AL, Keskin DB, Johnson T, Chandler P, Munn DH. Cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibit T cell responses. J Immunol (2002) 1950(168):3771–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sznurkowski JJ, Zawrocki A, Emerich J, Sznurkowska K, Biernat W. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase predicts shorter survival in patients with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (vSCC) not influencing on the recruitment of FOXP3-expressing regulatory T cells in cancer nests. Gynecol Oncol (2011) 122:307–12. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Curti A, Trabanelli S, Onofri C, Aluigi M, Salvestrini V, Ocadlikova D, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing leukemic dendritic cells impair a leukemia-specific immune response by inducing potent T regulatory cells. Haematologica (2010) 95:2022–30. 10.3324/haematol.2010.025924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Curti A, Pandolfi S, Valzasina B, Aluigi M, Isidori A, Ferri E, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by human leukemic cells results in the conversion of CD25- into CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood (2007) 109:2871–7. 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levina V, Su Y, Gorelik E. Immunological and nonimmunological effects of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase on breast tumor growth and spontaneous metastasis formation. Clin Dev Immunol (2012) 2012:173029. 10.1155/2012/173029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, Bradfield CA. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J Immunol (2010) 1950(185):3190–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Platten M, Ho PP, Youssef S, Fontoura P, Garren H, Hur EM, et al. Treatment of autoimmune neuroinflammation with a synthetic tryptophan metabolite. Science (2005) 310:850–5. 10.1126/science.1117634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Britan A, Maffre V, Tone S, Drevet JR. Quantitative and spatial differences in the expression of tryptophan-metabolizing enzymes in mouse epididymis. Cell Tissue Res (2006) 324:301–10. 10.1007/s00441-005-0151-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haber R, Bessette D, Hulihan-Giblin B, Durcan MJ, Goldman D. Identification of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase RNA in rodent brain. J Neurochem (1993) 60:1159–62. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuasa HJ, Takubo M, Takahashi A, Hasegawa T, Noma H, Suzuki T. Evolution of vertebrate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenases. J Mol Evol (2007) 65:705–14. 10.1007/s00239-007-9049-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller CL, Llenos IC, Dulay JR, Barillo MM, Yolken RH, Weis S. Expression of the kynurenine pathway enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase is increased in the frontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis (2004) 15:618–29. 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Minatogawa Y, Suzuki S, Ando Y, Tone S, Takikawa O. Tryptophan pyrrole ring cleavage enzymes in placenta. Adv Exp Med Biol (2003) 527:425–34. 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Suzuki S, Toné S, Takikawa O, Kubo T, Kohno I, Minatogawa Y. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in early concepti. Biochem J (2001) 355:425–9. 10.1042/0264-6021:3550425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Sahm F, Ott M, Tritschler I, Trump S, et al. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature (2011) 478:197–203. 10.1038/nature10491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bessede A, Gargaro M, Pallotta MT, Matino D, Servillo G, Brunacci C, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature (2014) 511:184–90. 10.1038/nature13323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.DiNatale BC, Murray IA, Schroeder JC, Flaveny CA, Lahoti TS, Laurenzana EM, et al. Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol Sci (2010) 115:89–97. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Siddiqui SS, Babu P. Kynurenine hydroxylase mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Gen Genet (1980) 179:21–4. 10.1007/BF00268441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol (1990) 215:403–10. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Van der Goot AT, Nollen EAA. Tryptophan metabolism: entering the field of aging and age-related pathologies. Trends Mol Med (2013) 19:336–44. 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Coburn C, Allman E, Mahanti P, Benedetto A, Cabreiro F, Pincus Z, et al. Anthranilate fluorescence marks a calcium-propagated necrotic wave that promotes organismal death in C. elegans. PLoS Biol (2013) 11:e1001613. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coburn C, Gems D. The mysterious case of the C. elegans gut granule: death fluorescence, anthranilic acid and the kynurenine pathway. Front Genet (2013) 4:151. 10.3389/fgene.2013.00151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van der Goot AT, Zhu W, Vázquez-Manrique RP, Seinstra RI, Dettmer K, Michels H, et al. Delaying aging and the aging-associated decline in protein homeostasis by inhibition of tryptophan degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:14912–7. 10.1073/pnas.1203083109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baillie DL, Chovnick A. Studies on the genetic control of tryptophan pyrrolase in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet (1971) 112:341–53. 10.1007/BF00334435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tartof KD. Interacting gene systems: I. the regulation of tryptophan pyrrolase by the vermilion-suppressor of vermilion system in Drosophila. Genetics (1969) 62:781–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tearle R. Tissue specific effects of ommochrome pathway mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet Res (1991) 57:257–66. 10.1017/S0016672300029402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roberts JE. Ocular phototoxicity. J Photochem Photobiol B (2001) 64:136–43. 10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00196-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beadle GW, Ephrussi B. Development of eye colors in Drosophila: transplantation experiments with suppressor of vermilion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1936) 22:536–40. 10.1073/pnas.22.9.536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Searles LL, Voelker RA. Molecular characterization of the Drosophila vermilion locus and its suppressible alleles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1986) 83:404–8. 10.1073/pnas.83.2.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Savvateeva-Popova EV, Popov AV, Heinemann T, Riederer P. Drosophila mutants of the kynurenine pathway as a model for ageing studies. Adv Exp Med Biol (2003) 527:713–22. 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Campesan S, Green EW, Breda C, Sathyasaikumar KV, Muchowski PJ, Schwarcz R, et al. The kynurenine pathway modulates neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease. Curr Biol (2011) 21:961–6. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Oxenkrug GF. The extended life span of Drosophila melanogaster eye-color (white and vermilion) mutants with impaired formation of kynurenine. J Neural Transm (2010) 1996(117):23–6. 10.1007/s00702-009-0341-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oxenkrug GF, Navrotskaya V, Voroboyva L, Summergrad P. Extension of life span of Drosophila melanogaster by the inhibitors of tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism. Fly (Austin) (2011) 5:307–9. 10.4161/fly.5.4.18414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Savvateeva EV, Popov AV, Kamyshev NG, Iliadi KG, Bragina JV, Heisenberg M, et al. Age-dependent changes in memory and mushroom bodies in the Drosophila mutant vermilion deficient in the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova (1999) 85:167–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Savvateeva E, Popov A, Kamyshev N, Bragina J, Heisenberg M, Senitz D, et al. Age-dependent memory loss, synaptic pathology and altered brain plasticity in the Drosophila mutant cardinal accumulating 3-hydroxykynurenine. J Neural Transm (2000) 1996(107):581–601. 10.1007/s007020070080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Powell-Coffman JA, Qin H. Invertebrate AHR homologs: ancestral functions in sensory systems. In: Pohjanvirta R, editor. The AH Receptor in Biology and Toxicology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; (2011). p. 405–11 [Google Scholar]