Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether the timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) differed by race and comorbidity among older (≥ 50 years) people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).

Methods. We conducted frequency and descriptive statistics analysis to characterize our sample, which we drew from 2005–2007 Medicaid claims data from 14 states. We employed univariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses to evaluate the relationship between race, comorbidity, and timely ART initiation (≤ 90 days post-HIV/AIDS diagnosis).

Results. Approximately half of the participants did not commence ART promptly. After we adjusted for covariates, we found that older PLWHA who reported a comorbidity were 40% (95% confidence interval = 0.26, 0.61) as likely to commence ART promptly. We found no racial differences in the timely initiation of ART among older PLWHA.

Conclusions. Comorbidities affect timely ART initiation in older PLWHA. Older PLWHA may benefit from integrating and coordinating HIV care with care for other comorbidities and the development of ART treatment guidelines specific to older PLWHA. Consistent Medicaid coverage helps ensure consistent access to HIV treatment and care and may eliminate racial disparities in timely ART initiation among older PLWHA.

Current trends in the epidemiology of HIV in the United States indicate that older persons (≥ 50 years) are a burgeoning population affected by HIV.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in 2009, older persons constituted 33% of all people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).2 Emerging data project that by 2020, half of all PLWHA will be aged 50 years or older.2 Within this age group, persons aged between 50 and 64 years account for the majority (89%) of all HIV diagnoses.1 As seen in the national data, racial/ethnic, gender, and regional disparities also exist in the HIV disease burden among older persons.1,3 Older African Americans and Hispanics are, respectively, 13 and 5 times more likely to receive an HIV diagnosis than are White Americans, and men are more likely to be diagnosed than are women.1 The southern United States is disproportionately burdened by HIV cases occurring in this age group.1,3 Surveillance reports showed that the southern United States accounted for the greatest number of HIV cases among all older persons in 2010.1,3

Besides the increased survival of PLWHA, various explanations have been offered for the HIV prevalence among older people in the United States. Older persons are more likely to underestimate their personal risk for contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections because they assume that HIV is an infection primarily affecting younger persons.4,5 Older women may also be more inclined to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse because of the minimal risk of pregnancy6,7 even though they are at increased risk for HIV during penetration because of the vaginal and cervical thinning that occurs during menopause.7,8 Ageism and stigma surrounding HIV testing in this age group7,9,10 as well as a failure of health care providers to inquire about and provide information on safe sex to this population are other reasons for the high HIV infection rates.7 Other factors include greater avenues for sexual activity such as Internet dating sites that target older persons11 and the increased availability of drugs for erectile dysfunction,2,7 both of which facilitate sexual partnerships among this age group. Lastly, older persons are too often left out of HIV prevention efforts, as the majority of HIV prevention programs target younger persons, African Americans, and men who have sex with men.12,13

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly changed the clinical course of HIV and enabled the long-term survival of PLWHA. However, older PLWHA are more likely to rapidly progress to AIDS and have shorter survival times than are younger persons, although they are more likely to be ART adherent.14–17 Among persons aged 50 years or older, African Americans and other minorities are also more likely to be diagnosed with HIV late in the course of the disease, contributing to disparities in HIV survival and mortality even with ART.1,2 Immune senescence18,19 and comorbidities20,21 are other factors unique to older PLWHA that may play a role in the clinical course of HIV. Studies have shown that older PLWHA have a less robust immunological response to ART, because of either diminished thymic function that occurs with aging or lower CD4 counts at baseline.18,19,22

Comorbidities such as coronary artery disease; diabetes mellitus; hypertension; dyslipidemia; bone, liver, and kidney disease; chronic respiratory disorders; cancers; and psychiatric and neurocognitive conditions are common among older persons.23,24 HIV is also associated with increased prevalence of these comorbidities.24 Comorbidities are more prevalent among older persons, especially older PLWHA, than they are among younger populations.2,20,21,25 Comorbidities can complicate and accelerate the HIV disease process, manifesting as frailty, organ and functional impairment, and increased likelihood of hospitalization and death.2,24–26 The increased prevalence of comorbidities may impact the clinical management of HIV/AIDS.20,21 These comorbidities may interfere with the timing of ART initiation, disrupt ART metabolism, or require drug treatment that may interact with ART, complicating HIV/AIDS disease treatment and survivability.20,21 However, research on the influence of comorbidities on ART receipt and initiation among older PLWHA is sparse, with the findings of 1 study showing that comorbidities did not influence ART receipt.27

Research examining the correlates of ART initiation or receipt has focused mainly on racial disparities in age-diverse populations.28–38 Although older PLWHA represent the growing face of HIV, are at higher risk for HIV disease progression, and have comorbidities that are likely to influence treatment decisions in this population, research examining the interaction of aging, race, and ART receipt and initiation is lacking. Because of this, we sought to determine the influence of race and comorbidity on the timely initiation of ART among older persons. We hypothesized that African Americans and persons with comorbidities would report delayed ART initiation.

METHODS

We used a retrospective cohort design with a study population that we abstracted from Medicaid claims data from 14 US states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2007. Persons from these states account for approximately one third of all US Medicaid enrollees and about half of all African American Medicaid enrollees in the United States.39 These states, mostly in the southern United States, also account for the greatest burden of HIV among older people.1 Medicaid is also the largest source of health coverage for PLWHA.40 We used Medicaid Analytic eXtract files, which are individual-level data files on health care utilization and include personal summary (demographic and enrollment data), inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and long-term care files for all enrollees in each state for each calendar year.

Patient Selection and Measures

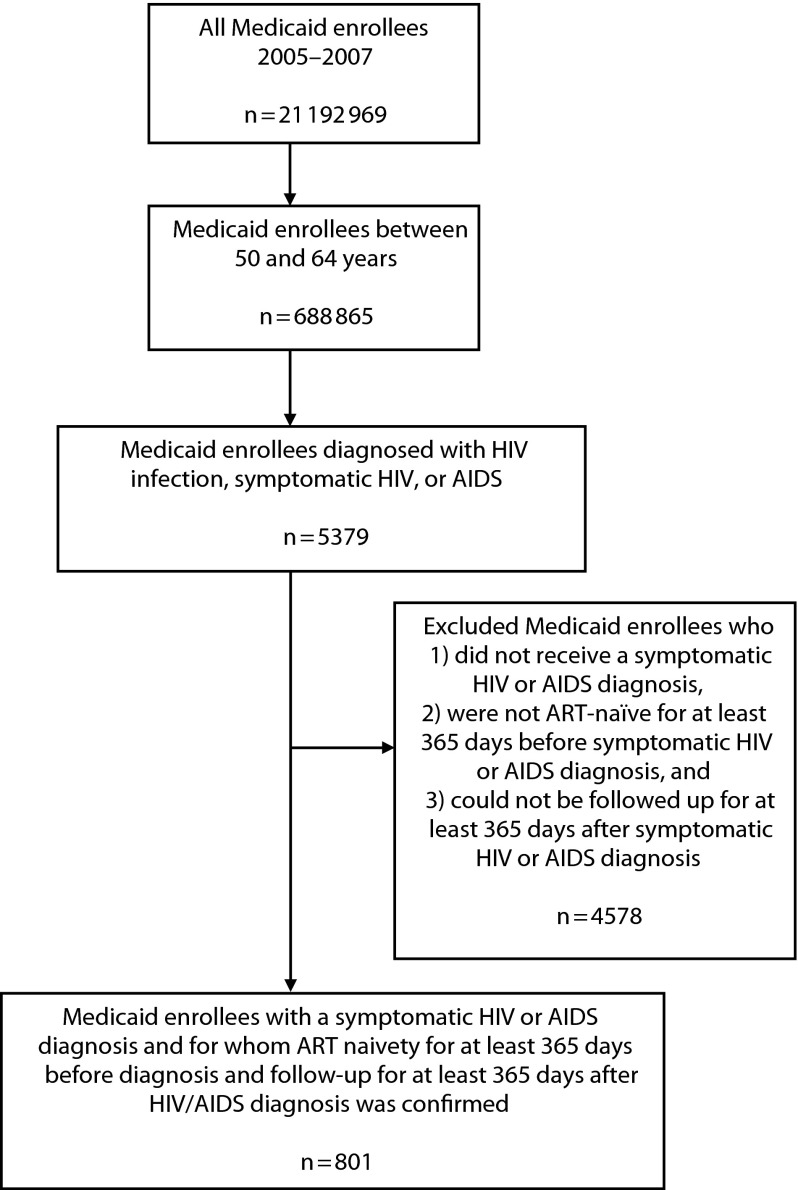

To be eligible for the study, participants had to (1) be aged between 50 and 64 years, (2) receive a diagnosis of symptomatic HIV or AIDS to be ART-eligible, and (3) be enrolled for at least 365 days before HIV/AIDS diagnosis to determine ART naïveté (medical records indicating no prior ART use) and 365 days after HIV/AIDS diagnosis to determine time to ART initiation. We excluded participants who did not meet all inclusion criteria. We selected participants aged between 50 and 64 years because most (89%) HIV/AIDS diagnoses occur in this age subgroup, and we wanted to minimize the number of dual eligible (Medicaid and Medicare) participants. Medicaid claims data do not include CD4 counts, so we limited study participants to those who had claims for symptomatic HIV disease or AIDS (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification41 code 042). We used the date of symptomatic HIV or AIDS diagnosis as our index date because the clinical guidelines at the time the data were collected recommended ART initiation upon receiving either diagnoses.42 Figure 1 illustrates the participant selection criteria we used in this study. Of the approximately 21 million Medicaid enrollees from the 14 states in 2006, 688 865 were aged between 50 and 64 years. Of this number, 5379 received a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS and 801 met our inclusion criteria.

FIGURE 1—

Flow diagram showing participant selection: Medicaid claims data, United States, 2005–2007.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

The independent variables were race (White, African American, and other races) and comorbidity (yes and no) at time of HIV/AIDS diagnosis. We included gender (male and female), residential status (urban and rural), age, and state of residence as covariates. We measured age as a continuous variable. We categorized participants who identified as non-White or non-African American as other because of their small sample size.

We used the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index43 to measure non–HIV-related comorbid medical conditions, using an algorithm developed by Quan et al.,44 and categorized them into 2 groups on the basis of whether any comorbidity was reported (0 = no; ≥ 1 = yes). We determined residential status, a covariate, by merging the Medicaid Analytic eXtract data with county-level data from the Area Resource File—a health data resource that includes a compilation of publicly available data such as population, environmental characteristics, and geographical descriptors (urban vs rural).45 We included gender, residential status, and age as covariates because of their role as conceptual confounders in ART receipt and initiation,33 and we included state of residence because of the varying state Medicaid eligibility criteria. Georgia was the reference state because it has one of the highest numbers and rates of persons living with a diagnosis of HIV.46 Our outcome variable of interest was time to initiation of ART. We measured time to initiation of ART as a continuous variable (in days) and as a dichotomized variable (≤ 90 days or > 90 days). We chose this time point because of its use as a benchmark in determining early or late engagement in HIV care47 and its use in previous research.48,49

Analysis

We conducted frequencies and descriptive statistics to characterize the sample overall and by race. We employed the χ2 test and analysis of variance to determine the association between race and categorical (gender, urban vs rural status, and comorbid status) and continuous (age) variables, respectively. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to evaluate whether time to ART initiation varied by race.

We conducted univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses to examine the influence of race and comorbidity on time to initiation of ART. We estimated the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for timely ART initiation and set a 2-tailed level of statistical significance at .05. We calculated a Kaplan–Meir survival curve to estimate the cumulative probability of ART initiation by race and comorbidity. We conducted all analyses with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the characteristics of our study sample overall and by race. Our sample was predominantly (75.0%) African American; Whites made up 15.9%. The remainder (9.1%) included all other races combined (Asian, non-Hispanic White, and Native American). Of all study participants, 54.9% were male, 83.3% of participants resided in urban areas, and 8.5% reported at least 1 comorbid condition. The mean age of our study sample was 54.5 years. Only half of our ART-eligible participants initiated ART promptly (≤ 90 days). The median duration to ART initiation was 96 days overall but 114 days for African Americans, the longest duration of all racial groups. There were no significant differences in comorbid status, gender, age, and median time to initiate ART by race. However, African Americans were significantly more likely to report urban residence (P < .01).

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics of Older People Living With HIV/AIDS Enrolled in Medicaid (n = 801) by Race: Medicaid Claims Data, United States, 2005–2007

| Variable | Total, No. (%), Mean ±SD, or Median (Q1, Q3) | African American, Total, No. (%), Mean ±SD, or Median (Q1, Q3) | White, Total, No. (%), Mean ±SD, or Median (Q1, Q3) | Other, Total, No. (%), Mean ±SD, or Median (Q1, Q3) | P |

| Total | 801 (100.0) | 601 (75.0) | 127 (15.9) | 73 (9.1) | |

| Comorbiditya | |||||

| Yes | 68 (8.5) | 54 (9.0) | 6 (4.7) | 8 (11.0) | .21 |

| No | 733 (91.5) | 547 (91.0) | 121 (95.3) | 65 (89.0) | |

| Gendera | |||||

| Female | 361 (45.1) | 279 (46.4) | 48 (37.8) | 34 (46.6) | .19 |

| Male | 440 (54.9) | 322 (53.6) | 79 (62.2) | 39 (53.5) | |

| Residential statusa | |||||

| Urban | 667 (83.3) | 513 (85.4) | 102 (80.3) | 52 (71.2) | < .01 |

| Rural | 134 (16.7) | 88 (14.6) | 25 (19.7) | 21 (28.8) | |

| Age,b y | 54.5 ±3.7 | 54.6 ±3.7 | 54.2 ±3.6 | 54.4 ±3.9 | .52 |

| Timely ART initiationa | |||||

| Yes, ≤ 90 d | 397 (49.6) | 289 (48.1) | 64 (50.4) | 44 (60.3) | .18 |

| No, > 90 d | 404 (50.4) | 312 (51.9) | 63 (49.6) | 29 (39.7) | |

| Time to ART initiation,c d | 96 (13, 365) | 114 (13, 365) | 66 (15, 365) | 28 (7, 365) | .16 |

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; Q = quartile.

χ2 test.

Analysis of variance.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

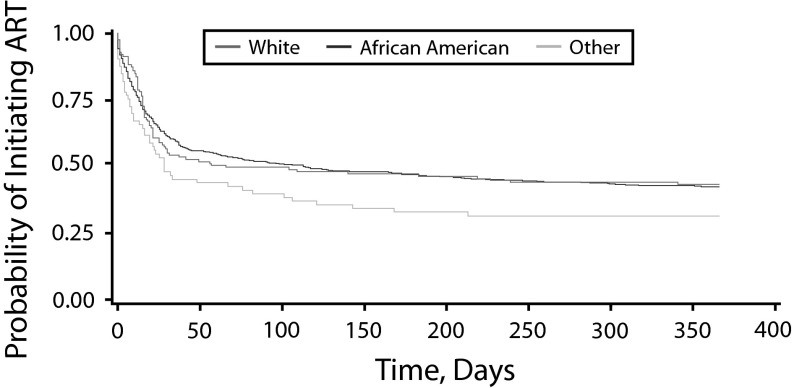

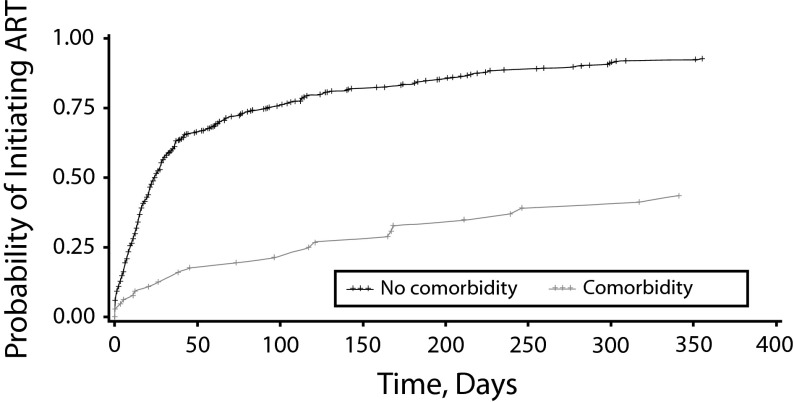

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted HR of the univariate and multivariable Cox regression models. Race was not independently associated with time to initiation of ART in the univariate analysis, but comorbidity was. Participants who reported a comorbidity were significantly less likely to initiate ART promptly (HR = 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.29, 0.66; P < .01) than were participants who did not. Other covariates, including gender, residential status, age, and state of residence were not associated with prompt ART initiation. After we adjusted for covariates, there were still no differences in timely ART initiation by race but comorbidity remained significantly associated with timely ART initiation (HR = 0.40; 95% CI = 0.26, 0.61; P < .01). ART-eligible participants without any comorbidity were 2.5 times as likely to initiate ART promptly upon receiving a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS. The covariates were not significantly associated with time to initiate ART. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed no racial differences in the ART initiation rate (Figure 2). Figure 3 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curve, showing that older PLWHA without any comorbidity initiated ART at a more rapid rate than did older PLWHA with a comorbidity.

TABLE 2—

Univariate (Unadjusted) and Multivariable (Adjusted) Cox Regression Models Showing Relationship Between Variables and Timely Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Among Older People Living With HIV/AIDS: Medicaid Claims Data, 2005–2007

| Variable | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) |

| Race | ||

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.01 (0.78, 1.30) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.28) |

| Other | 1.40 (0.98, 2.02) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.74) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.43* (0.29, 0.66) | 0.40* (0.26, 0.61) |

| Gender | ||

| Female (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 1.05 (0.88, 1.26) | 1.13 (0.94, 1.37) |

| Residential status | ||

| Urban (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 1.13 (0.89, 1.44) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.48) |

| Age | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Adjusted for state

*P < .01.

FIGURE 2—

Kaplan–Meier estimate of time to antiretroviral therapy initiation by race: Medicaid claims data, United States, 2005–2007.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

FIGURE 3—

Kaplan–Meier estimate of time to antiretroviral therapy initiation by comorbidity: Medicaid claims data, United States, 2005–2007.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy.

DISCUSSION

Older PLWHA are the changing face of HIV in the United States but have received less focused attention as a public health priority. Correspondingly, there is limited research examining deficits in prompt ART initiation by race and comorbidity despite their respective importance and prevalence in this population. Our data are among the first to demonstrate the influence of these factors on the timely initiation of ART among older PLWHA. We hypothesized that African Americans and participants with comorbidities would not initiate ART promptly. Contrary to our hypothesis, the results of our study did not demonstrate any racial disparities in the prompt initiation of ART in our study sample. Our inability to detect racial disparities in this study could be attributed to numerous factors. Because our sample was drawn from Medicaid claims data, all study participants had consistent health insurance coverage and presumably the same level of health care access during the study period (2005–2007). Consequently, persons with barriers to accessing care, persons who disengaged from care during the study period, uninsured and underinsured persons, and other vulnerable groups (most of which include disproportionate minority representation) were underestimated or excluded from the study sample. The consistent source of health care in this population before HIV infection may have also facilitated health literacy, trust in health care providers, and motivation to commence treatment, consequently mitigating racial disparities in timely ART initiation in this study sample. Additionally, because Medicaid data contain only claims information, we could not include and control for key social determinants of health such as income, educational level, and employment status, all of which drive racial disparities.50

Although no study to our knowledge has examined racial disparities in ART initiation or receipt among older persons exclusively, many studies have examined racial disparities in ART initiation and receipt on age-diverse populations with mixed findings. Consistent with our findings, some previous studies did not demonstrate racial differences in ART receipt or initiation28,31,32,51,52 and about half of ART-eligible persons commenced ART promptly.52 However, other studies have identified racial disparities in ART receipt or initiation, noting that African Americans and non-Whites were less likely than were Whites to initiate or receive ART.29,33–37 Most of the participants in the aforementioned studies were younger than 50 years. Our study therefore contributes to the existing literature on aging and HIV by examining the influence of race on the timely initiation of ART initiation among older PLWHA.

The findings also suggest that consistent access to HIV care, facilitated by Medicaid and other HIV/AIDS discretionary programs, may mitigate racial disparities in ART initiation. For example, a recent study on Medicaid enrollees who had consistent access to HIV care over time has demonstrated the absence of disparities between African Americans and Whites in ART receipt.52 Another study, by Moore et al., also attributed the absence of racial disparities in ART receipt in their study to consistent access to HIV care facilitated by the Ryan White Program.28 Similarly, a study using participants in the US Military HIV Natural History Study, who had consistent access to HIV care, also noted the absence of racial disparities in ART initiation.51 Because of these findings, the decision by many states—particularly southern states with large racial/ethnic minority populations and high rates of HIV/AIDS—not to expand Medicaid and the uncertainty surrounding the future of the Ryan White Program will likely limit access to consistent HIV care and may hinder efforts at eliminating racial disparities in Medicaid nonexpansion states.54

Another key finding was that older PLWHA with at least 1 comorbidity were more likely to report delayed ART initiation. This finding may be because of the risk of aggravating an existing organ dysfunction55,56 or concerns related to drug–drug (ART and comorbid medication) interaction.57,58 For example, tenofovir and emtricitabine, both HIV medications, are directly nephrotoxic and may worsen renal impairment.55,56 Atazanavir, another HIV medication, reduces the potency of warfarin, a blood thinner used in patients with atrial fibrillation,57 whereas proton-pump inhibitors used in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease decreases the absorption of atazanavir, hindering its effectiveness.58 There are also no controlled data on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of ART among older PLWHA; nor are there established treatment guidelines or recommendations for older PLWHA, especially those with comorbidities.42 All these factors may make health care providers reluctant to commence HIV treatment, resulting in delayed ART initiation among older PLWHA.

Because of the increase in comorbidities as people age, older PLWHA may receive care from multiple providers for their comorbidities (e.g., nephrologist, endocrinologist, cardiologist) in addition to their HIV care. Failure to integrate and coordinate medical care and medication history—a challenge across many aspects of the health care system—can lead to gaps and delays in care, including delayed ART initiation. Psychiatric comorbidities such as depression may also negatively affect the readiness and motivation of treatment-eligible patients to promptly commence ART.59,60 Comorbidities may therefore drive delayed ART initiation and, consequently, shorter survival times and elevated mortality among older PLWHA.

Our findings indicate that as the incidence and prevalence of HIV/AIDS among older people continues to grow, the impact of comorbidities on HIV treatment warrants additional attention. This might suggest the need for improved integration and coordination of care and medication prescription practices among all health care providers, similar to patient-centered medical homes or accountable care organizations to harmonize the management of HIV/AIDS and comorbidities without undermining HIV treatment efficacy.54 Other services such as check-in appointments to allow dose adjustments and evaluate drug tolerance and medication substitution should also be incorporated into the routine health care of older PLWHA on ART. Leverage of electronic health records both within and across practices to ensure that older PLWHA initiate ART in a timely manner and are retained in care is critical to the optimal management of HIV/AIDS and other comorbidities. Finally, incorporating nonmedical modalities such as lifestyle modifications (e.g., exercise, healthy diet, and alcohol and smoking cessation) into the concurrent management of comorbidities in older PLWHA on ART in lieu of medications when applicable may prove beneficial.

Strengths and Limitations

As with any study, ours was subject to limitations. First, our data did not allow us to control for clinical indicators such as CD4 count and viral load, both of which may influence ART initiation. Second, our data precluded us from controlling for variables such as income, educational level, employment status, HIV/AIDS stigma, mode of transmission, substance use, and stressful life events, variables that affect ART initiation and receipt.31,34,61,62 Additionally, because we used Medicaid claims data, we underrepresented older PLWHA who were uninsured or underinsured and those who had alternate insurance coverage. Finally, we used Medicaid claims data from enrollees in predominantly southern states, so our sample is not nationally representative. Persons receiving Medicaid must meet eligibility criteria, which is set by each state and therefore restricts Medicaid enrollees to certain categories of people. Thus, our sample may be neither representative of nor generalizable to all older PLWHA.

Despite these limitations, our study has its strengths. Our study is among the few that have examined factors influencing the timely initiation of ART in older PLWHA. Because most of the participants in our study were diagnosed with HIV/AIDS as older persons, we could determine ART naïveté and control for the aging cohort effect on our outcome.63 Our study design was a retrospective, not cross-sectional, cohort study, which enabled us to establish temporal trends (from time of diagnosis and comorbidity to ART initiation) and conduct time-to-event analysis rather than associations. Finally, because we used Medicaid claims data, patients and health care providers were unaware that this information would be used for research, reducing the likelihood of reporter bias.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that comorbidities affect timely ART initiation in older PLWHA. There were no disparities in ART initiation by race. Understanding that HIV tends to be diagnosed at a later disease stage in older persons and that only half of our study participants received ART promptly, it is critical that strategies to support prompt ART initiation be developed to prevent incident HIV infections, halt rapid clinical progression, and improve long-term survival.64 To meet the challenges of the HIV epidemic and meet the objectives of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy,65 HIV treatment and prevention efforts should include a targeted focus on older adults. Health care providers should inquire about risk factors for HIV in older patients, promptly link older PLWHA to HIV care, and maintain coordinated care with specialty providers, especially for patients with comorbid conditions.

Emphasizing healthy lifestyle modifications and scheduling follow-up appointments to evaluate and manage concurrent comorbidities, drug tolerance, and drug adjustments are equally important. It is essential that older PLWHA with comorbidities receive coordinated care without undermining ART efficacy and timeliness. To this end, specific treatment guidelines for older persons are required. Finally, we call for further research to better understand the impact of aging on HIV and HIV treatment and to develop HIV/AIDS education and prevention interventions that target older persons.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ grant 1R24HS019470-01) as part of the Multiple Chronic Conditions Research Collaborative.

Note. The findings and conclusions of this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection

This research was conducted with approval of the institutional review board of the Morehouse School of Medicine, which also waived the requirement for individual informed consent.

References

- 1.Linley L, Prejean J, An Q, Chen M, Hall HI. Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV diagnoses among persons aged 50 years and older in 37 US States, 2005–2008. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1527–1534. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks JT, Buchacz K, Gebo KA, Mermin J. HIV infection and older Americans: the public health perspective. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1516–1526. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prejean J, Tang T, Hall HI. HIV diagnoses and prevalence in the southern region of the United States, 2007–2010. J Community Health. 2013;38(3):414–426. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9633-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy JA, Ory MG, Crystal S. HIV/AIDS interventions for midlife and older adults: current status and challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(suppl 2):S59–S67. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savasta AM. HIV: associated transmission risks in older adults—an integrative review of the literature. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004;15(1):50–59. doi: 10.1177/1055329003252051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindau ST, Leitsch SA, Lundberg KL, Jerome J. Older women’s attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: a community-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(6):747–753. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among older Americans. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans. Accessed May 3, 2014.

- 8.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(suppl 1):S1–S18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):781–790. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams M, Oye J, Parker T. Sexuality of older adults and the internet: from sex education to cybersex. Sexual Relationship Therap. 2003;18(3):405–425. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of evidence-based HIV behavioral interventions. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/complete.html. Accessed May 3, 2014.

- 13.Abara W, Coleman JD, Fairchild AJ, Gaddist B, White J. A faith-based community partnership to address HIV/AIDS in the southern US: implementation, challenges, and lessons learned. J Relig Health. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9789-8. published online October 31, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):542–553. doi: 10.1086/590150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabar S, Weiss L, Costagliola D. HIV infection in older patients in the HAART era. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57(1):4–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez JL, Moore RD. Greater effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on survival in people aged > or =50 years compared with younger people in an urban observational cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(2):212–218. doi: 10.1086/345669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adler WH, Baskar PV, Chrest FJ, Dorsey-Cooper B, Winchurch RA, Nagel JE. HIV infection and aging: mechanisms to explain the accelerated rate of progression in the older patient. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;96(1–3):137–155. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(97)01888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Althoff KN, Justice AC, Gange SJ et al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2469–2479. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e6d14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lederman MM, McKinnis R, Kelleher D et al. Cellular restoration in HIV infected persons treated with abacavir and a protease inhibitor: age inversely predicts naive CD4 cell count increase. AIDS. 2000;14(17):2635–2642. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simone MJ, Appelbaum J. HIV in older adults. Geriatrics. 2008;63(12):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(3):453–472. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manfredi R, Chiodo F. A case-control study of virological and immunological effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with advanced age. AIDS. 2000;14(10):1475–1477. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Council of Aging. Healthy aging. Available at: http://www.ncoa.org/assets/files/pdf/FactSheet_HealthyAging.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2014.

- 24.Rodriguez-Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK et al. Co-morbidities in persons infected with HIV: increased burden with older age and negative effects on health-related quality of life. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(1):5–16. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilbourne AM, Justice AC, Rabeneck L, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Weissman S. VACS 3 Project Team. General medical and psychiatric comorbidity among HIV-infected veterans in the postHAART era. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(12):S22–S28. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlando G, Meraviglia P, Cordier L et al. Antiretroviral treatment and age-related comorbidities in a cohort of older HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2006;7(8):549–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah SS, McGowan JP, Smith C, Blum S, Klein RS. Comorbid conditions, treatment, and health maintenance in older persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(10):1238–1243. doi: 10.1086/343048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Bartlett JG. Improvement in the health of HIV-infected persons in care: reducing disparities. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(9):1242–1251. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Gebo KA, Agwu AL. HIV Research Network. Disparities in receipt of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults (2002–2008) Med Care. 2012;50(5):419–427. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanna DB, Buchacz K, Gebo KA et al. Trends and disparities in antiretroviral therapy initiation and virologic suppression among newly treatment-eligible HIV-infected individuals in North America, 2001–2009. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1174–1182. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pence BW, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Whetten K, Thielman N, Mugavero MJ. The influence of psychosocial characteristics and race/ethnicity on the use, duration, and success of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(2):194–201. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ace7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(1):41–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meditz AL, MaWhinney S, Allshouse A et al. Sex, race, and geographic region influence clinical outcomes following primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(4):442–451. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R et al. Racial and gender disparities in receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy persist in a multistate sample of HIV patients in 2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(1):96–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King WD, Minor P, Ramirez Kitchen C et al. Racial, gender and geographic disparities of antiretroviral treatment among US Medicaid enrolees in 1998. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(9):798–803. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guwani JM, Weech-Maldonado R. Medicaid managed care and racial disparities in AIDS treatment. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;26(2):119–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemly DC, Shepherd BE, Hulgan T et al. Race and sex differences in antiretroviral therapy use and mortality among HIV-infected persons in care. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(7):991–998. doi: 10.1086/597124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oramasionwu CU, Skinner J, Ryan L, Frei CR. Disparities in antiretroviral prescribing for Blacks and Whites in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(11):1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S, Senteio C, Felizzola J, Rust G. Racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected pregnant Medicaid enrollees, 2005–2007. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):e46–e53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid and HIV/AIDS. Available at: http://kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/medicaid-and-hivaids. Accessed May 3, 2014.

- 41.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammer SM, Saag MS, Schechter M et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2006;296(7):827–843. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Health Resource and Services Administration. Area Health Resources Files. Available at: http://arf.hrsa.gov. Accessed May 2, 2014.

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2014.

- 47.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paz-Bailey G, Pham H, Oster AM et al. Engagement in HIV care among HIV-positive men who have sex with men from 21 cities in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(suppl 3):348–358. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0605-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aliyu MH, Blevins M, Parrish DD et al. Risk factors for delayed initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in rural north central Nigeria. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):e41–e49. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829ceaec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Milwood) 2005;24(2):325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson EN, Roediger MP, Landrum ML et al. Race/ethnicity and HAART initiation in a military HIV infected cohort. AIDS Res Ther. 2014;11(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, McGoy SL, Dawes D, Fransua M, Rust G, Satcher D. The potential for elimination of racial-ethnic disparities in HIV treatment initiation in the Medicaid population among 14 southern states. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e96148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reif S, Whetten K, Thielman N. Association of race and gender with use of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals in the Southeastern United States. South Med J. 2007;100(8):775–781. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3180f626b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abara W, Heiman HJ. The Affordable Care Act and low-income persons living with HIV/AIDS: looking forward in 2014 and beyond. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.05.002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Izzedine H, Launay-Vacher V, Deray G. Renal tubular transporters and antiviral drugs: an update. AIDS. 2005;19(5):455–462. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162333.35686.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Post FA, Moyle GJ, Stellbrink HJ et al. Randomized comparison of renal effects, efficacy, and safety with once-daily abacavir/lamivudine versus tenofovir/emtricitabine, administered with efavirenz, in antiretroviral-naive, HIV-1-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(1):49–57. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181dd911e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Busti AJ, Hall RG, Margolis DM. Atazanavir for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(12):1732–1747. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.17.1732.52347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomilo DL, Smith PF, Ogundele AB et al. Inhibition of atazanavir oral absorption by lansoprazole gastric acid suppression in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(3):341–346. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yun LW, Maravi M, Kobayashi JS, Barton PL, Davidson AJ. Antidepressant treatment improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy among depressed HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(4):432–438. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000147524.19122.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vranceanu AM, Safren SA, Lu M et al. The relationship of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression to antiretroviral medication adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(4):313–321. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mugavero MJ, Norton W, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl 2):S238–S246. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cunningham WE, Markson LE, Andersen RM et al. Prevalence and predictors of highly active antiretroviral therapy use in patients with HIV infection in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(2):115–123. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoeymans N, Feskens EJ, van den Bos GA, Kromhout D. Age, time, and cohort effects on functional status and self-rated health in elderly men. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(10):1620–1625. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eaton JW, Johnson LF, Salomon JA et al. HIV treatment as prevention: systematic comparison of mathematical models of the potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV incidence in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National HIV/AIDS strategy. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/nhas.html. Accessed May 2, 2014.