Short abstract

Attempts to prevent trafficking are increasing the problems of those who migrate voluntarily

Trafficking in women and children is now recognised as a global public health issue as well as a violation of human rights. The UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children states that trafficking involves force, threat, or fraud and intent to exploit individuals.1 Intermediaries often smuggle victims across international borders into illegal or unsafe occupations, including agriculture, construction, domestic labour, and sex work. A recent study identified trafficking to be associated with health risks such as psychological trauma, injuries from violence, sexually transmitted infections, HIV and AIDS, other adverse reproductive health outcomes, and substance misuse.2 These risks are shaped by lack of access to services in a foreign country, language barriers, isolation, and exploitative working conditions. However, as this article shows, efforts to reduce trafficking may be making conditions worse for voluntary migrants.

Response to trafficking

Multinational, governmental, and non-governmental groups working to counter trafficking sometimes misinterpret the cultural context in which migration occurs.3 They often seek to eradicate labour migration rather than target specific instances of exploitation and abuse.4,5 Regulatory measures, such as introducing new requirements for documentation and strengthening of border controls, criminalise and marginalise all migrants, whether trafficked or not. This exacerbates their health risks and vulnerability by reducing access to appropriate services and social care. Such approaches do not adequately distinguish between forced and voluntary migrants, as it is extremely difficult to identify the motivations of migrants and their intermediaries before travel.6

We illustrate these concerns with evidence from research conducted among child migrants in Mali who had been returned from the Ivory Coast and Vietnamese sex workers in Cambodia. The evidence draws from studies conducted between 2000 and 2002.7,8 In both settings, the international media has reported emotively on the existence of “child slaves,” “sex slaves,” and “trafficking” and oriented donors and nongovernmental organisations to this agenda.9-11

Child migrants in Mali

Although no substantiated figures exist, an estimated 15 000 Malian children have been “trafficked” to the cocoa plantations in the Ivory Coast.12 This study responded to a demand from several international non-governmental organisations that wanted to improve their understanding of the situation.7 We compiled a sampling frame with the assistance of nongovernmental organisations working with children and their governmental partners. It included young people from communities deemed to be at high risk of trafficking, as well as intercepted or repatriated children thought to have been trafficked. However, a survey of nearly 1000 young people from this list found that only four could be classified as having been deceived, exploited, or not paid at all for their labour. Rather, young people voluntarily sought employment abroad, which represented an opportunity to experience urban lifestyles, learn new languages, and accumulate possessions. For both boys and girls, the experience provided a rite of passage with cultural as well as financial importance.

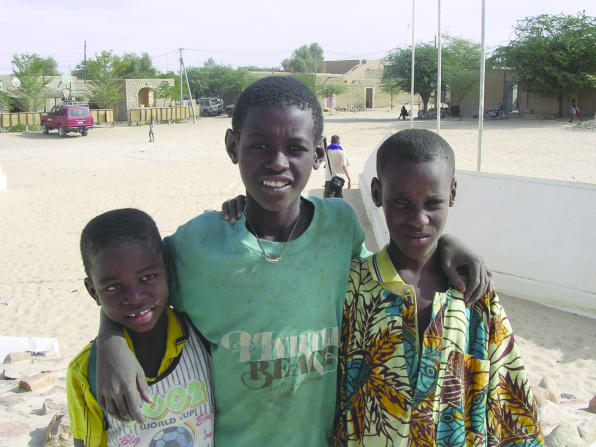

Figure 1.

Malian child migrants

For many of these migrants, movement across international borders depended on assistance from intermediaries, often family members. In Mali there is a longstanding tradition of using intermediaries to facilitate a range of social and economic activities, such as looking for employment, negotiating purchases, handling disputes, and even seeking a spouse. Our research found that intermediaries could protect the migrants during their journey and help them search for work. In destination areas, they advocated for young people in cases of non-payment of salary or abrupt termination of employment. Migrants also relied on intermediaries to negotiate with corrupt authorities that demanded bribes at international borders. Classifying such assistance as “trafficking” simplifies a much deeper cultural reality.

Local anti-trafficking policies and interventions, however, have not acknowledged these complex dynamics and have instead posed obstacles to safe, assisted migration. For example, interviews with Malian legal experts showed that new legislative measures do not enable them to distinguish between a trafficker with intent to exploit and an intermediary who, for a fee, facilitates a young migrant's journey and search for housing and employment. Local anti-trafficking surveillance committees have been established; these have come to view all migration as negative and local leaders seem to seek to arrest children if they attempt to leave. At the national level, a new child's passport is required for all children under the age of 18 who wish to travel. In reality, young people find the document difficult to obtain, and failure to possess it provides an easy excuse for law enforcement officers to extort additional bribes at borders.

These measures discourage community members from assisting in traditional labour migration and have the potential to force migrants to rely increasingly on corrupt officials to waive travel documents or provide forgeries. Clandestine migrants are generally more difficult to reach at destination points, as they may be reluctant to seek health care or other help if they fear being forcibly repatriated or detained. Child migrants who left home of their own free will report being returned home against their wishes by non-governmental organisations, only to leave for the border again a few days later.

The study found that rehabilitation centres for trafficked children run by two non-governmental organisations in the Malian town of Sikasso were usually empty. Such interventions are neither appropriate nor cost effective and do not tackle the exploitative conditions encountered by children in the Ivory Coast. Children would be better served through services offered in the Ivory Coast or support through protective networks of intermediaries and community members.

Vietnamese sex workers in Cambodia

As with Malians in the Ivory Coast, it is difficult to obtain accurate data on the number of Vietnamese migrants in Cambodia. Some estimates suggest that up to 10 000 Vietnamese women are sex workers in Cambodia.13 The research presented here was conducted in collaboration with a local non-governmental organisation as part of a wider investigation of sex workers' perceptions, motivations, and experiences.8 The study formed one component of a service delivery programme to about 300 brothel based Vietnamese sex workers in Svay Pak district, Phnom Penh. Before the research, medical services, outreach, and counselling had been provided to sex workers for over five years, and a trusting relationship had been established between non-governmental organisation staff and both sex workers and brothel managers. Young, female, Vietnamese speaking project staff familiar to the sex workers conducted indepth interviews with 28 women and focus group discussions with 72 participants to explore patterns of entry into sex work.

Most women knew before they left Vietnam that they would be engaged in sex work under a system of “debt bondage” to a brothel. The work would repay loans made to them or their families. Some women showed clear ambition in their choices to travel to Cambodia for sex work, citing economic incentives, desire for an independent lifestyle, and dissatisfaction with rural life and agricultural labour. As in Mali, intermediaries from home communities were instrumental in facilitating safe migration. Many women were accompanied by a parent, aunt, or neighbour who provided transport, paid bribes to border patrols, and negotiated the contract with brothel managers.

Of the 100 participants in this qualitative study, six women reported having been “tricked” into sex work or betrayed by an intermediary. Many sex workers, however, expressed dissatisfaction with their work conditions or stated that they had not fully appreciated the risks they would face, such as clients who refused to use condoms, coercion from brothel owners, and violence from both clients and local police.

A policy focus on combating “trafficking” again seemed to threaten rather than safeguard migrants' health and rights. Local and international non-governmental organisations conducted raids on brothels during which sex workers were taken to “rehabilitation centres,” often against their will. Police sometimes assisted in these raids, although they also conducted arrests independently.

Our research found that “rescued” women usually returned to their brothel as quickly as possible, having secured their release through bribes or by summoning relatives from Vietnam to collect them. Furthermore, police presence in the raids scared off custom, thus reducing earnings, increasing competition for clients, and further limiting sex workers' power in negotiating improved work conditions. Bribes and other costs were added to sex workers' debts, increasing their tenure in the brothel and adding pressure to take on additional customers or agree to condom-free sex to maximise income. Raids and rescues could also damage the relationship between service providers and brothel managers, who restricted sex workers' mobility, including access to health care, to avoid arrest. These findings mirror recent reports from other sex worker communities throughout the region.14-16

The way forward

Our research in Mali and Cambodia shows disturbing parallels in ways that anti-trafficking measures can contribute to adverse health outcomes. Without wanting to minimise the issue of trafficking, these studies show that a more flexible and realistic approach to labour migration among young people is required. The needs of vulnerable young migrants, whether trafficked or not, can be met only through comprehensive understanding of their motivations and of the cultural and economic contexts in which their movements occur. Criminalising migrants or the industries they work in simply forces them “underground,” making them more difficult to reach with appropriate services and increasing the likelihood of exploitation.

We do not dispute that in both settings migrants have suffered hardship and abuse, but current “anti-trafficking” approaches do not help their problems. The agendas need to be redrawn so that they reflect the needs of the populations they aim to serve, rather than emotive reactions to sensationalised media coverage. This requires deeper investigation at both local and regional levels, including participatory research to inform interventions from the experiences of the migrants and their communities. From the research that we have conducted in Mali and Cambodia, we recommend the following:

Policy makers need to recognise that migration has sociocultural as well as economic motivations and seeking to stop it will simply cause migrants to leave in a clandestine and potentially more dangerous manner. Facilitating safe, assisted migration may be more effective than relying on corrupt officials to enforce restrictive border controls.

Instead of seeking to repatriate migrants, often against their will, interventions should consider ways to provide appropriate services at destination points, taking into consideration specific occupational hazards, language barriers, and ability to access health and social care facilities.

Programmes aimed at improving migrants' health and welfare should not assume that all intermediaries are “traffickers” intending to exploit migrants. Efforts to reach migrants in destination areas could use intermediaries.

Organisations that have established good rapport with migrant communities should document cases of abuse and advocate for improved labour conditions. In the case of sex work, however, this can be politically difficult. For example, the United States Agency for International Development recently announced its intention to stop funding organisations that do not explicitly support the eradication of all sex work.

Ultimately, trafficking and other forms of exploitation will cease only with sustainable development in sending areas combined with a reduction in demand for cheap, undocumented labour in receiving countries. Non-governmental organisations and government partners therefore need to focus on the root causes of rural poverty and exploitation of labour as well as mitigating the health risks of current migrants. At the moment, trafficking is big business not just for traffickers but also for the international development community, which can access funds relatively easily to tackle the issue without investing in a more comprehensive understanding of the wider dynamics shaping labour migration.

Summary points

Anti-trafficking interventions often ignore the cultural context of migration and can increase migrants' risk of harm and exploitation

Attempts to eradicate migration of young people for work will increase their reliance on corrupt officials and use of clandestine routes

In Mali and Cambodia, intermediaries often assist safe migration and should not necessarily be seen as exploitative “traffickers”

Programmes should provide migrants with appropriate services and help advocate for better work conditions in destination countries

Contributors and sources: The authors have considerable practical experience of research on reproductive and sexual health issues among vulnerable groups. JB conducted operations research in South East Asia from 1997-2001 on community based HIV prevention interventions, primarily with migrant sex workers. SC has worked in Mali for 15 years, mainly in the Mopti region which has high rates of out-migration. AD has worked for many years in Mali in women's health and women's rights.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.United Nations. Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United National Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime. New York: United Nations, 2000.

- 2.Zimmerman C, Yun K, Shvab I, Watts C, Trappolin L, Treppete M, et al. The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents. Findings from a European study. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2003.

- 3.Butcher K. Confusion between prostitution and sex trafficking. Lancet 2003;361: 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall P. Globalization, migration and trafficking: some thoughts from the South-East Asian region. Bangkok: UN Inter-Agency Project on Trafficking in Women and Children in the Mekong Sub-region, 2001. (Occasional paper No 1.)

- 5.Taran PA, Moreno-Fontes G. Getting at the roots. UN Inter-Agency Project Newsletter 2002;7: 1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coomaraswamy R. Integration of the human right of women and the gender perspective: violence against women: report of the special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. New York: UN Economic and Social Council, 2000.

- 7.Castle S, Diarra A. The international migration of young Malians: tradition, necessity or rite of passage? London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2003.

- 8.Busza J, Schunter BT. From competition to community: participatory learning and action among young, debt-bonded Vietnamese sex workers in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters 2001;9: 72-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobak L. For sale: the innocence of Cambodia. Ottawa Sun 1996. Oct 24.

- 10.Chocolate slaves carry many scars. Daily Telegraph 2001. Apr 24.

- 11.Child slavery: Africa's growing problem. CNN 2001. Apr 17.

- 12.United States Agency for International Development. Trafficking in persons: USAID's response. Washington, DC: USAID Office of Women in Development, 2001: 10-6.

- 13.Unicef. Unicef supports national seminar on human trafficking. www.unicef.org/vietnam/new080.htm (accessed 11 Nov 2003).

- 14.Jones M. Thailand's brothel busters. Mother Jones 2003. Nov/Dec.

- 15.Phal S. Survey on police human rights violations in Toul Kork. Phnom Penh: Cambodia Women's Development Association, 2002.

- 16.Sutees R. Brothel raids in Indonesia—ideal solution or further violation? Research for Sex Work 2003;6: 5-7. [Google Scholar]