Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To characterize the integration of phytotherapy in primary health care in Brazil.

METHODS

Journal articles and theses and dissertations were searched for in the following databases: SciELO, Lilacs, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Theses Portal Capes, between January 1988 and March 2013. We analyzed 53 original studies on actions, programs, acceptance and use of phytotherapy and medicinal plants in the Brazilian Unified Health System. Bibliometric data, characteristics of the actions/programs, places and subjects involved and type and focus of the selected studies were analyzed.

RESULTS

Between 2003 and 2013, there was an increase in publications in different areas of knowledge, compared with the 1990-2002 period. The objectives and actions of programs involving the integration of phytotherapy into primary health care varied: including other treatment options, reduce costs, reviving traditional knowledge, preserving biodiversity, promoting social development and stimulating inter-sectorial actions.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past 25 years, there was a small increase in scientific production on actions/programs developed in primary care. Including phytotherapy in primary care services encourages interaction between health care users and professionals. It also contributes to the socialization of scientific research and the development of a critical vision about the use of phytotherapy and plant medicine, not only on the part of professionals but also of the population.

Keywords: Phytotherapy, utilization; Plants, Medicinal; Primary Health Care; Health Services; Review

Abstract

OBJETIVO:

Caracterizar a inserção da fitoterapia em ações e programas na atenção primária à saúde no Brasil.

MÉTODOS:

Realizou-se levantamento bibliográfico de artigos de periódicos e teses e dissertações nacionais. Foram utilizadas as bases de dados: SciELO, Lilacs, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science e Portal de Teses Capes no período entre janeiro de 1988 e março de 2013. Foram analisados 53 estudos originais sobre ações, programas e aceitação de uso de fitoterápicos e plantas medicinais na atenção primária à saúde do Sistema Único de Saúde. Foram analisados dados bibliométricos, características das ações e programas, local e sujeitos envolvidos na pesquisa, tipo e objetivo dos estudos selecionados.

RESULTADOS:

Entre 2003 e 2013 houve aumento das publicações em diferentes áreas de conhecimento, comparado ao período de 1990-2002. As ações e programas de fitoterapia inseridos nos serviços de atenção primária à saúde variaram em objetivos e ações: inserir outras opções terapêuticas, reduzir custos, resgatar saberes tradicionais, preservar a biodiversidade, promover o desenvolvimento social, estimular ações intersetoriais, interdisciplinares, de educação em saúde e a participação comunitária.

CONCLUSÕES:

Nos últimos 25 anos houve aumento pequeno da produção científica sobre ações/programas de fitoterapia desenvolvidos na atenção primária à saúde. A inserção da fitoterapia nos serviços de atenção primária estimulou a interação entre usuários e profissionais de saúde. Também contribui para socialização da pesquisa científica e desenvolvimento da visão crítica tanto dos profissionais quanto da população sobre o uso adequado de plantas medicinais e fitoterápicos.

INTRODUCTION

The trajectory of the use of phytotherapeutics and medicinal plants in primary health care in Brazil has been stimulated by social movements, guidelines from various national health conferences and recommendations from the World Health Organization. The publication of Resolution 971, on May 3, 2006 and Act 5813, on June 22, 2006, which regulated the Política Nacional de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares (National Policy on Integrative and Complimentary Practices) and the Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Fitoterápicos (National Policy on Medicinal and Phytotherapeutic Plants), were decisive steps towards introducing the use of medicinal and phytotherapeutic plants in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). 9 , a

Before these policies, and later stimulated by them, some states and municipalities institutionalized actions and programs with medicinal plants in primary health care. The use of phytotherapy has diverse motives, such as increasing therapeutic resources, reviving traditional knowledge, preserving biodiversity, encouraging agroecology, social development and environmental, popular and ongoing education. 3 Until now there have been few reviews of studies that record and analyze these trials, as the topic is relatively seldom valued within the area of collective health.

The objective of this study was to characterize the integration of phytotherapy in actions and programs in primary health care in Brazil.

METHODS

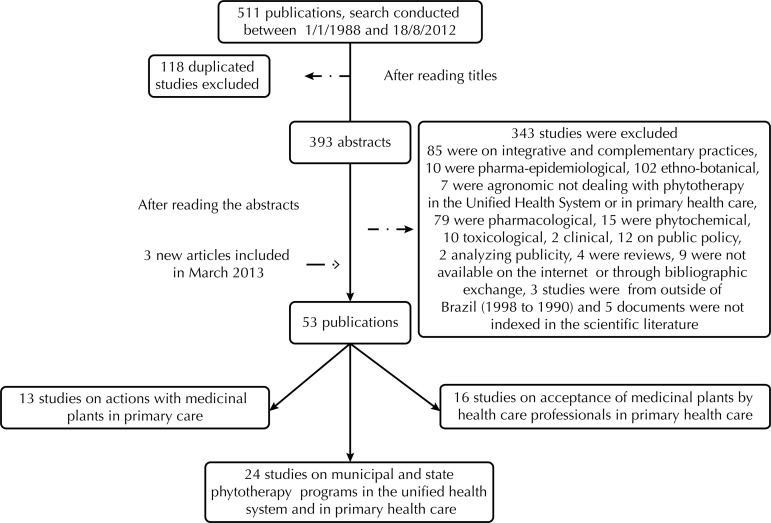

Journal articles and theses and dissertations were searched for in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, SciELO, Lilacs and Portal de Teses Capes, from January 1988 to March 2013. A combination of keywords and descriptors were used in the search strategy. In international databases the following descriptors were searched for: “Herbal” AND “Primary Health Care”; “Plant Preparations” AND “Primary Health Care”; phytotherapy and “Primary Health Care”; “Phytotherapeutic Drugs” AND “Primary Health Care”; “Herbal” AND “Family Health”; phytotherapy AND “Family Health”; “Plant Preparations” AND “Family Health”; “Complementary Therapies” AND phytotherapy AND “Primary Health Care”; “Complementary Therapies” AND phytotherapy AND “Family Health”; “Herbal” AND “Single Health System”; phytotherapy AND “Single Health System”; in the databases SciELO, Lilacs and Theses Portal Capes the keywords searched for were: fitoterapia AND “ Saúde Pública ”, fitoterapia AND “ Saúde da Família ”, “ Plantas Medicinais ” AND “ Saúde da Família ”, “ Plantas Medicinais ” AND “ Atenção Primária à Saúde ”, “ Plantas Medicinais ” AND “ Saúde Coletiva ”. Of the total 511 studies found, only the primary studies that related to/analyzed the integration of actions/programs and/or acceptance/use/prescription of medicinal plants in the context of primary health care services were selected. The following were excluded: editorials, journalistic material, studies evaluating clinical and technical protocols, critical reviews, commentaries, literature reviews, educational manuals, personal information, phytochemical or pharmacognosial research, pharmacological and toxicological studies. Three publications from between 1988 and 1990 were also excluded as they were not available online or in public federal or state university archives, as loans or as copies. In total, 53 publications were selected for analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure. Flowchart of selection of publications.

Tables 1 , 2 and 3 show the relationship and bibliometric characterization of the selected publications (author, year of publication, type of study, intervention reference group and objective/focus of the study). The characterization of the actions and programs developed in the context of Brazilian primary health care is systematized in Table 4 . Cases that involved continued and institutionalized activities in municipalities were considered as programs. Actions or use of medicinal plants by medical professionals and users as a therapeutic resource (indication/prescription) and/or educational, interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral activities developed within primary health care services, were considered as activities.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies on the development and implementation of phytotherapeutic programs in primary health care. Brazil, 1990-2012.

| Authors/Year | Study type | Study location and subjects | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa (1990)a | Case study | Goiânia, GO | Implementation and development of phytotherapy in the municipal Ayurvedic therapy hospital. |

| Araújo (2000)4 | Qualitative research | Londrina, PR; unidentified patients | Interaction between biomedical and traditional knowledge on healing with medicinal plants in the municipality. |

| Negreiro (2002)c | Pharmacology-epidemiological study | Pereiro, CE; 64 patients | Use of phytotherapeutic medicines on primary health care in the municipality. |

| Teixeira (2003)e | Case study | Juiz de Fora, MG; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a phytotherapy program in the municipality. |

| Ogava, Pinto, Kikuchi, Menegueti, Martins, Coelho et al (2003)29 | Experiment report | Maringá, PR; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of the phytotherapeutic Verde Vida program in the municipality. |

| Sacramento (2004)37 | Experiment report | Vitória, ES; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a phytotherapeutic and homeopathic program in the municipality. |

| Graça (2004)16 | Experiment report | Curitiba, PR; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of the Verde Vida program in the municipality. |

| Carneiro & Pontes (2004)10 | Experiment report | Itapipoca, CE; unidentified patients | Use of phytotherapy in primary health care in the municipality. |

| Pires, Borella, Raya (2004)33 | Experiment report | Ribeirao Preto, SP; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a phytotherapeutic and homeopathic program in the municipality. |

| Reis, Leda, Pereira, Tunala (2004)35 | Experiment report | Rio de Janeiro, RJ; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a phytotherapeutic program in the municipality. |

| Michiles (2004)26 | Experiment report | State of Rio de Janeiro; unidentified patients | Situational diagnosis of the municipalities within the state of Rio de Janeiro that provide phytotherapeutic services. |

| Guimarães, Medeiros, Vieira (2006)17 | Experiment report | Betim, MG; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of the Farmácia Viva (Living Drugstore) in the municipality. |

| Silva, Gondim, Nunes, Sousa (2006)41 | Study on the use of medicines | Maracanaú,CE; 1,095 patients | Research on the use of medicinal plants in primary health care in the municipality. |

| Pontes, Monteiro, Rodrigues (2006)34 | Qualitative research | Brasília, DF; 3 professionals (1 nurse and 2 physicians) and 26 patients | Use of medicinal plants in the treatment of pediatric health problems in the district. |

| Matos (2006)24 | Experiment report | Fortaleza, CE; unidentified patients | Model of Farmácia Viva (Living Drugstore) for integrating phytotherapy into the public health network in the municipality. |

| Diniz (2006)12 | Experiment report | Londrina, PR; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a phytotherapeutical program in the municipality. |

| Oliveira, Simões, Sassi (2006)30 | Experiment report | State of Sao Paulo; unidentified patients | Situation of the phytotherapeutic health care in the state. |

| Silveira (2007)d | Study on the use of medicines | Fortaleza, CE; 178 patients | Use and frequency of adverse reactions to phytotherapeutics within the Farmácia Viva (Living Drugstore) program in the municipality. |

| Ministério da Saúde (2008)b | Experiment report | State of Amapá; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of a Center of Reference for natural treatments. |

| Ministério da Saúde (2008)b | Experiment report | Campinas, SP; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of the Botica da Família (Family Drugstore) in the municipality. |

| Brasiliero, Pizziolo, Matos, Germano, Jamal (2008)8 | Study on the use of medicines | Governador Valadares, MG; 2,454 patients | Profile of the use of medicinal plants in the Programa Saúde da Família (PSF – Family Health Program) in the municipality. |

| Nagai & Queiróz (2011)27 | Social study | Campinas, SP, 37 professionals (11 physicians, 18 nurses, 1 psychologist, 1 occupational therapist, 1 dentist, 1 speech therapist, 1 biomedical therapist, 1 sociologist | Social study on the perception of traditional, complementary and alternative practices among health professionals connected to the municipality’s public health network. |

| Santos, Sousa, Gurgel, Bezerra, Barros (2011)39 | Qualitative research | Recife, CE; 20 professionals and managers (focal group) | Participation of political figures in the evolution of municipal policies on integrative practices. |

| Bruning, Mosegui, Viana (2012)9 | Qualitative research | Cascavel and Foz do Iguaçu, PR; 10 professionals (5 nurses, 3 physicians, 1 nursing assistant and 1 nursing technician) | Learnings from managers and health professionals (primary health care) on phytotherapy, in the municipalities. |

|

| |||

| Total | 24 publications | ||

a Barbosa MA, Baptista SS. A fitoterapia como prática de saúde: o caso do hospital de terapia ayurvedica de Goiânia. Rio de Janeiro: Escola de Enfermagem Anna Nery da UFRJ; 1990.

b Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Práticas integrativas e complementares em saúde: uma realidade no SUS. Rev Bras Saude Fam [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2014 Mar 22];9(Ed. Espec.):3-76. Available from: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/revistas/revista_saude_familia18_especial.pdf

c Negreiros MSC. Uso do medicamento fitoterápico na atenção primária do município de Pereiro-Ceará [specialization monograph]. Fortaleza: Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade Estadual do Ceará; 2002.

d Silveira PF. Perfil de utilização e monitoramento de reações adversas a fitoterápicos do Programa Farmácia Viva em uma unidade básica de saúde de Fortaleza [dissertation]. Fortaleza: Faculdade de Farmácia, Odontologia e Enfermagem da UFC; 2007.

e Teixeira JBP. Memória institucional da fitoterapia em Juiz de Fora [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto de Medicina Social da UERJ; 2003.

Table 2. Characteristics of studies concerning actions with medicinal plants and phytotherapeutic medicines developed in the context of primary health care services. Brazil, 1990-2012.

| Authors/Year | Study type | Study location and subjects | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chechetto (2003)c | Case study | Tubarao, SC; 30 participants from the Câmara Setorial (Sectorial Chamber) and/or from the Associação Catarinense de Plantas Medicinais (ACPM − Medicinal Plants Association of Santa Catarina) | Implementation and development of the Rede Catarinense de Plantas Medicinais (Medicinal Plants Network of Santa Catarina). |

| Bieski (2005)a | Ethnobotanical study | Cuiabá, MT; 693 patients | Importance of local traditional knowledge for the implementation of medicinal plants programs in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). |

| Damas (2005)d | Qualitative research | Florianópolis, SC; 5 physicians and 20 volunteers from OFVV | Learnings from physicians from the Health Centre and volunteers from the Oficina de Fitoterapia Vida Verde (OFVV – Green Life Phytotherapy Workshop) regarding phytotherapy and the use of medicinal plants. |

| Leite & Schor (2005)20 | Case study | Itajaí, SC; 17 health professionals (3 nursing assistants, 2 physicians, 2 dentists and 1 nurse; 8 patients and 1 extension program coordinator) | Significance of the use of medicinal plants for health professionals and health unit patients. |

| Cavallazzi (2006)b | Qualitative research | Florianópolis, SC; 23 health professionals (11 physicians, 5 dentists and 7 nurses) 265 patients | Recognition of medicinal plants and phytotherapeutic medicines used in primary health care in the southern zone of the municipality. |

| Tomazzoni, Negrelle, Centa (2006)44 | Ethnobotanic study | Cascavel, PR; 50 families | Planning and introduction of the use of phytotherapeutic medicines in the municipality's basic health care service. |

| Negrelle, Tomazzoni, Ceccon, Valente (2007)28 | Ethnobotanic study | Cascavel, PR; 50 families | Initial diagnosis for establishing the use of phytotherapeutic medicines in the municipality's basic health care service. |

| Guizardi & Pinheiro (2008)18 | Case study | Vitória and Vila Velha, ES; 18 representatives from pastoral care in health and the municipal health council | Community phytotherapeutic pharmacies in pastoral health care. |

| Ministério da Saúde (2008)e | Experiment report | Quatro Varas, CE; unidentified patients | Implementation and development of the integrated community mental health movement in the municipality. |

| Piccinini (2008)f | Etnobotânico | Porto Alegre, RS; 49 patients | Initial diagnosis for establishing the use of phytotherapeutic medicines in public health programs in the municipality. |

| Santos (2008)g | Qualitative research | Rio de Janeiro, RJ; 3 managers (1 physician, 1 agronomist, 1 pharmacist) and 5 health professionals (1 physician, 1 nurse, 1 biologist, 1 pharmacist, 1 health agent) and 14 patients | Interfaces between phytotherapeutic services and the Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF – Family Health Strategy) in the municipality. |

| Paranaguá, Bezerra, Souza, Siqueira (2009)32 | Quali-quantitative research | Goiânia, GO; 35 community health agents | Integrative practices used by the population in the Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF – Family Health Strategy) and patients views regarding the practices. |

| Santos & Tesser (2012)40 | Participatory research | Florianópolis, SC; unidentified patients | Method for implementing and promoting access to integrative and complementary practices including phytotherapy, and an advise facility for the local management in primary health care. |

|

| |||

| Total | 13 publications | ||

a Bieski IGC. Plantas medicinais aromáticas no Sistema Único de Saúde da região sul de Cuiabá-MT [monograph of specialization]. Lavras: Departamento de Agricultura da Universidade Federal de Lavras; 2005.

b Cavallazzi ML. Plantas medicinais na Atenção Primária à Saúde [dissertation]. Florianópolis: Centro de Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2006.

c Chechetto F. Rede Catarinense de Plantas Medicinais: uma abordagem transdisciplinar para a saúde coletiva [dissertation]. Tubarão: Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina; 2003.

d Damas FB. A fitoterapia com estratégia terapêutica na comunidade do Saco Grande II, Florianópolis/SC [end of course project]. Florianópolis: Curso de Graduação em Medicina da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2005.

e Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Práticas integrativas e complementares em saúde: uma realidade no SUS. Rev Bras Saude Fam [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2014 Mar 22];9(Ed. Espec.):3-76. Available from: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/revistas/revista_saude_familia18_especial.pdf

f Piccinini GC. Plantas medicinais utilizadas por comunidades assistidas pelo Programa Saúde da Família,em Porto Alegre: subsídios à introdução da fitoterapia em atenção primária em saúde [thesis]. Porto Alegre: Faculdade de Agronomia da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2008.

g Santos MAP. Estratégia de saúde da família and fitoterapia: avanços, desafios and perspectivas [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Estácio de Sá; 2008.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies on the acceptance of use and prescription of medicinal plants and phytotherapeutic medicines, by health professionals, in the context of primary health care. Brazil, 1990-2013.

| Authors/Year | Study type | Study location and subjects | Study focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alvim & Cabral (2001)1 | Qualitative research | Rio de Janeiro, RJ; 10 nurses | Contexts of medicinal plant use in the institutional nursing environment. |

| Alvim et al (2006)2 | Qualitative research | Uninformed location, 15 nurses | Ethical and legal implications of the use of medicinal plants in nursing. |

| Lima Jr. & Dimenstein (2006)21 | Qualitative research | Natal, RN; 30 dentists | Acceptance among public service dental-surgeons in the municipality, concerning the possibility of integrating phytotherapy into basic health care. |

| Taufne, Ferraço, Ribeiro (2006)42 | Ethnobotanical study | Santa Tereza and Marilândia, ES; 100 patients | Use of medicinal plants by patients from public health units in the municipalities of Santa Teresa, ES and Marilândia, ES. |

| França, Marques, Lira, Higino (2007)15 | Quali-quantitative research | Recife, CE; 37 health professionals (16 nurses, 13 physicians, 8 dentists) | The perception held by health professionals from basic health care teams regarding the use of medicinal plants in oral health. |

| Fontanella, Speck, Piovezan, Kulkamp (2007)13 | Descriptive field survey | Tubarao, SC; 88 families | Analysis of knowledge, access and acceptance regarding integrative and complementary health practices in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). |

| Dutra (2009)a | Quali-quantitative | Anápolis, GO; 220 health professionals (15 physicians, 71 nurses, 120 nursing technicians, 5 physiotherapists, 7 pharmacists and 2 dentists) and 380 patients | Use of medicinal plants phytotherapeutic medicines by health professionals and the population of the municipality. |

| Bastos & Lopes (2010)7 | Quali-quantitative | Joao Pessoa, PB; 15 nurses | Knowledge of nurses on phytotherapy and difficulties found in implementing this therapeutic approach in family health units. |

| Badke, Bodó, Silva, Ressel (2011)5 | Qualitative research | Unspecified location, Rio Grande do Sul; 10 patients | Everyday life of community dwellers attending a family health unit in a municipality of Rio Grande do Sul, relating to the therapeutic use of medicinal plants in health care. |

| Marques, Vale, Nogueira, Mialhe, Silva (2011)23 | Quali-quantitative | Sao Joao da Mata, MG; 35 patients | Knowledge and acceptance of integrative and complementary therapies and pharmaceutical care by Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) patients. |

| Rosa, Câmara, Béria (2011)36 | Qualitative research | Canoas, RS; 27 health professionals (physicians) | Cases and uses of phytotherapy in basic health care and factors related to the objectives of the therapy. |

| Tiago & Tesser (2011)43 | Exploratory research | Florianópolis, SC; 177 professionals (82 physicians and 95 nurses) | Perceptions held by professionals from the Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF – Family Health Strategy) regarding integrative and complementary practices. |

| Machado, Czermainski, Lopes (2012)22 | Case study series | Porto Alegre, RS; 21 health units coordinators (ESF and UBS) | Perceptions held by managers on introducing phytotherapeutic medicines in health care. |

| Cruz & Sampaio (2012)11 | Qualitative research | Unspecified location, 11 health professionals (1 physician, 1 nurse, 2 nursing assistants, 5 community health agents) | Use of complementary practices in a community within the reach of a family health unity. |

| Fontenele, Sousa, Carvalho, Oliveira (2013)14 | Quali-quantitative | Teresina, PI; 68 health professionals (36 nurses, 18 physicians, 14 dentists) | Knowledge of managers and health professionals on phytotherapy, its use and public policies involved. |

| Sampaio, Oliveira, Kerntopf, Brito Jr., Menenzes (2013)38 | Qualitative research | Crato, CE; 15 nurses | Knowledge of nurses on the use of phytotherapy in the Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF – Family Health Strategy). |

|

| |||

| Total | 16 publications | ||

a Dutra MG. Plantas medicinais, fitoterápicos and saúde pública: um diagnóstico situacional em Anápolis, Goiás [dissertation]. Anápolis: UniEvangélica; 2009.

Table 4. Main characteristics of phytotherapy actions and program consolidated in Brazilian primary health care, 1990-2013.

| Location | Basic characteristics of the phytotherapy actions and programs consolidated in primary health care |

|---|---|

| Amapá, APd | Reference Center for natural treatment; introduces greater diversity of Integrative and Complementary Practices in Brazil; institutionalized by state law 10,068/2007. The experience is based on cultural diversity, including indigenous, of the state of Amapá, and also on the biodiversity of the Amazon Rainforest. Interculturality is the background that guides the work practices developed in partnership with midwives, river dwellers and indigenous healers. |

| Betim, MG17 | Appeared due to the need to seek alternatives to control the high cost of medicines and their side effects. As well as increasing interest and need to guide users in the correct use of plant medicine. The program was in partnership with public and private networks in the municipality: Serviço Assistencial Salão do Encontro , Agriculture Secretariat, Environmental Secretariat, Health Surveillance. The inter-disciplinary team was formed of an agronomist, a pharmacist, an agricultural technician, a doctor, nurse, social worker, dentist, community health agents and a physiotherapist. |

| Campinas, SP27 | In Campinas, phytotherapy was implemented through establishing a Farmácia de Manipulação Botica da Família established by municipal ordinance 13/2001, based on prior history of primary health care initiatives in the municipality. The aim was to respect knowledge, customs and practices, providing education to broaden local culture and stimulate correct use of medicinal plants. |

| Cuiabá, MTc | The practices of cultivating medicinal and herbal plants in Cuiabá take place through the Phytotherapy, Medicinal and Herbal Plant Program, created in July 2004 and regulated by Decree 4,188/2004 by the Cuiabá Health Secretariat in Mato Grosso. The program aims to guarantee access to the rational use of medicinal plants and phytotherapeutic medicines safely and efficaciously and with quality, contributing to the development of this sector in Brazil. Medicinal plant gardens were established in health care units and treatment homes and phytotherapy medicines are distributed through the health care network, community education activities, training for professionals, identifying plants and producing publicity material to promote the program and praise awareness among professionals. |

| Curitiba, PR16 | This was the result of an intersectoral and multi-professional project created in 1997 with the aim of providing medicinal plants with botanical identification and scientifically tested for use in medical and dental prescriptions. Moreover, stimulating the use of medicinal plants in the community followed the recommendations of environmental education. The program was incentivized by the Municipal Environmental Secretariat, which coordinated the Integration Program for children and adolescents in partnership with the Universidade Federal do Paraná and the State Universities of Maringá and Ponta Grossa. The partnerships with the universities contributed to training the pharmacists of the future and stimulated the development of the national pharmaceutical industry in the region. |

| Florianópolis, SC41 | Permanent educational actions regarding medicinal plants in Florianópolis/SC were established in six health care units in 2012. The phytotherapy-related actions were supported by the Didactic Garden of Medicinal Plants of the Hospital Universitário da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina and by other local associations. The actions that were developed were: workshop for recognizing medicinal plants aimed at community health agents, didactic gardens in primary health care units, permanent education activities on medicinal plants for doctors, dentists, nurses and pharmacists and creating a municipal treatment memorandum. In the Sul de Ilha health care center, the use of medicinal plants is part of the local community culture, a factor that motivates the professionals to become qualified in this area. The phytotherapy workshop by the Associação Vida Verde Florianópolis/SC , created 28 June 1996, was an initiative of the health department of the Paróquia São Francisco Xavier, in Saco Grande II, Florianópolis/SC, in partnership with women in the community (willing to study, produce and distribute phytotherapy products) and the Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina . The main aim was to spread solidarity in the community, rescuing popular knowledge of medicinal plants and to integrate knowledge in order to improve quality of life. |

| Fortaleza, CE24 | The oldest experience in Brazil, influencing the creation of actions/programs regarding medicinal plants and phytotherapy in primary health care. The project was called Farmácias Vivas . It was created by Francisco José de Abreu Matos of the Universidade Federal do Ceará , in 1984, with the aim of developing methodology of interaction between popular knowledge and science based on a social approach to guide use of medicinal plants based on botanical identification and to create a reference of phytotherapy pharmaceutical formulas accessible to the population of the Northeast. The Farmácias Vivas project includes a set of actions: ethno-botanical field survey or bibliographical research, recording and validating medicinal plants, collecting plants in the field, training human resources, setting up a Farmácia Viva unit, producing informative material and popular education. Farmácia Viva is a great school and a great example to the world of effective social technology that aids treatment of around 80.0% of common illness in primary care, e.g., skin problems, respiratory and digestive problems, rheumatic pain, intestinal parasites and labial and genital herpes. After its creation in the state of Ceará, it became a national reference for the whole country and for structuring ordinance 886/2010. |

| Foz do Iguaçu, PR9 | The Itaipu herbalist was created in 2005 and contains 18 types of plants to treat 10 common illnesses. In 2007, the first training pf doctors, nurses, pharmacists and dentists took place in partnership with the Instituto Brasileiro de Plantas Medicinais (Brazilian Institute of Medicinal Plants). In order to produce the primary material, 54 agriculturists were trained and established in 17 units to demonstrate the cultivation of medicinal plants and provide technical assistance and rural extension activities. |

| Goiânia, GOb | The Goiânia Phytotherapy Project was created in 1986 through an agreement between the Goiás Health Secretariat, the Ministry of Health and the Instituto Brasileiro de Ciência e Tecnologia Maharishi . In Goiânia, Ayurvedic phytotherapy was used. In 1987 an outpatient service was established, with a small phytotherpay laboratory. In 1988, the Ayurvedic Phytotherapy Outpatient clinic was transferred to a wing of the former Hospital Juscelino Kubitschek . The Hospital de Medicina Alternativa is recognized throughout Brazil and internationally as a reference for integrated public health practices. The hospital cultivates around 60 species of medicinal plants in its garden to prepare phytotherapies and to preserve them. |

| Itajaí, SC20 | In Itajaí/SC, the insertion of medicinal plants was an initiative of the arterial hypertension control program in partnership with the extension project by the Universidade do Vale do Itajaí , named the university extension in family health project, covering professors and students of speech therapy, psychology, dentistry, medicine, nursing, nursing and pharmacy courses. The program encourages solidarity, exchanging experiences, linking the individual with life and with the health care team, the social group and humanization. |

| Itapipoca, CE10 | Begun in 1999, with the support of the Municipal Health Secretariat, the Universidade Federal do Ceará , the Fundação Cearense de Pesquisa e Célula de Fitoterapia do Estado do Ceará , social reform support program, with the aim of incentivizing women (who use medicinal plants) to make homemade remedies so as to improve their families health and quality of life, based on botanically identified plants and scientific evidence. |

| Juiz de Fora, MGf | In partnership with the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora , the Society for improving neighborhoods, children, family and health departments, community associations. The aim of this program was to recover popular knowledge and raise awareness of the correct use of medicinal plants in popular medicine. To do this, it was decided to follow regional medicinal plant based medicine, as well as experimental and scientific proof of therapeutic effects. |

| Londrinas, PR4,12 | Established in 1996. The aim was to establish a dialogue between two culturally different universes: popular knowledge and biomedicine. The backdrop to these discussions was the humanization of popular practices and of universal health care in the official services. The project counted on the partnership of care and educational institutions and resulted in the construction of a plant medicine unit in partnership with a variety of local institutions. The program had therapeutic gardens and six industrialized phytotherapies, three of which were psychiatric remedies, aiming to de-medicinalize psychotropic users. |

| Maracanaú, CE42 | Begin in 1992. Its basic structure was composed of a garden with four plots for cultivating medicinal plants and a laboratory of manipulation. The program dispenses phytoterapy medicines to the community through prescriptions from a family health care strategy health care professional. |

| Maringá, PR36 | Officially established in September 2000. The program is supported by the Universidade Estadual de Maringá . It is a pharmacy, following the format established in Resolution 33/2,000 with the aim of providing the population with safe, effective and cheap treatment alternatives. |

| Pereiro, CEe | Begun in 1995 with the establishment of a medicinal plant garden in which there is a technician with medicinal plant knowledge. In 1997, a bio-chemical pharmacist and an agronomist were contracted and the project was broadened according to the instructions of the Farmácia Viva in Ceará. A memorandum was drawn up and a phytotherapy guide. The aim of the project was to meet the population’s needs, taking into consideration cost-benefit and user satisfaction with the treatment response. Phytotherapy medicines were distributed in primary health units, dispensed by the municipal pharmacy in the hospital. The project was supported by the Universidade Federal do Ceará , the Centro Estadual de Fitoterapia (Fortaleza, CE), municipal prefectures, health secretariats and hospitals and health centers. |

| Pindamonhangaba, SP37 | 136 discussions on medicinal plants took place between 1992 and 2010, with 3,626 participants. The municipality provided didactic gardens and phytotherapy medicines. The actions were coordinated by the municipality’s Secretariat of Social Assistance. |

| Presidente Castello Branco, SCa | The aim of the project was to have plant nurseries of vegetable species in home gardens, in schools and in primary care units in the municipality. The initiative was linked to the “ Programa Castellense de coleta seletiva de lixo ”, waste collection program that was a multisectoral project (with municipal administration) linking all of the secretariats and carrying out actions aiming at sustainability, recycling waste, producing organic fertilizer and municipal development. In 2013, the municipality began permanent education actions on medicinal plants for health care professionals, linking educational, health and agricultural workers. It is considered a pioneering intersectorial initiative to insert phytptherapy in the east of Santa Catarina state. |

| Quatro Varas, CE11 | Established in 1988 by Airton Barreto. The aim of the project was to reduce use of psychotropic medicines in cases suffering from panic attacks and to defend the human rights of inhabitants of the Pirambú favela. Moreover, it sought to synthesize popular and biomedical actions intervening in health determinants. |

| Recife, CE43 | Phytotherapy actions in Recife are developed in a center supporting integrative practices and in primary health care units. The actions are guided on the theoretical reference model of defending life and the Paidéia method, (Co-management of collectives, Extended Clinic, Home, Singular Therapeutic Projects and Matrix Support) |

| Ribeirao Preto, SP31,37 | Established in 1992 and regulated by municipal law 8,778/2000 supported by the Sao Paulo state Health Secretariat, the Municipal health conferential and the municipal health council. The municipality had a forest garden, a formula manipulation laboratory, Farmácia Viva in schools, crèches, health care units and community bodies together with family health strategy teams. |

| Rio de Janeiro, RJ29,39 | Stimulated by the Programa Estadual de Plantas Medicinais regulated by state law 2,537/1996. It sought to establish public policies in the area of preservation, research and use of medicinal plants. Moreover, the program provided interaction with other public health programs, sectors and services of the health secretariat and other secretariats in the prefecture in Paquetá, working in the Pedro Bruno municipal school garden, where interaction took place between adolescents and the elderly. |

| Sao Paulo, SP37 | The program to produce phytotherapy and medicinal plants was created by municipal law 14,903/2009 and regulated by municipal decree 51,435/2010 instituting the municipal program of phytotherapy and medicinal plant production in the city of Sao Paulo. The city of Sao Paulo has a municipal health secretariat executive group and a coordinator of sub-prefectures, a municipal relation of phytotherapy that conducted a course on medicinal plants in the municipal school of gardening ( Parque Ibirapuera ), in 2011, with 60 places in the fifth year of the course, 4 multiprofessional courses of 30h in cultivating medicinal plants and a phytotherapy action day in June 2011. |

| Vila Velha, ES23 | Home phytotherapy pharmacy developed by the health department based on solidarity. What the health department did was to establish a counterweight to devices and mechanisms of power that configure the health field, creating new possibilities to constitute citizens’ rights. |

| Vitória, ES23,41 | Established in 1996, by law 4,352. The most notable initiative was the “ Cultivando Saúde: Horta em Casas ” project, which aimed to prevent disease by establishing gardens in wasteland. |

aAntonio GD. Fitoterapia na Atenção Primária à Saúde: interação de diferentes saberes e práticas de cuidado [thesis]. Florianópolis: Centro de Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2013.

bBarbosa MA, Baptista SS. A fitoterapia como prática de saúde: o caso do hospital de terapia ayurvedica de Goiânia. Rio de Janeiro: Escola de Enfermagem Anna Nery da UFRJ; 1990.

cBieski IGC. Plantas medicinais aromáticas no Sistema Único de Saúde da região sul de Cuiabá-MT [monograph of specialization]. Lavras: Departamento de Agricultura da Universidade Federal de Lavras; 2005.

d Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica. Práticas integrativas e complementares em saúde: uma realidade no SUS. Rev Bras Saude Fam [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2014 Mar 22];9(Ed. Espec.):3-76. Available from: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/revistas/revista_saude_familia18_especial.pdf

eNegreiros MSC. Uso do medicamento fitoterápico na atenção primária do município de Pereiro-Ceará [monograph of specialization]. Fortaleza: Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade Estadual do Ceará; 2002.

f Teixeira JBP. Memória institucional da fitoterapia em Juiz de Fora [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto de Medicina Social da UERJ; 2003.

RESULTS

In the studies analyzed we observed an increase in the number of publications after 1990. Between 2003 and 2012 the number of publications produced was greater, compared to the period between 1990 and 2002. This could be related to the introduction of the National Policy on Integrative and Complementary Practices, b and the National Policy on Medicinal Plants, c in 2006, which may have been decisive in the development of integrative practices in primary care. Though small, there has been an increase in scientific production on phytotherapy in primary health care services over the past 25 years, possibly motivated by the institutionalization of the practice by the cited national policies, b , c which developed specific health legislations that can be consulted online via the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA – Brazilian Health Surveillance Agency) website. a

With regard to the publications, we observed the integration of actions and programs using medicinal plants with diverse characteristics, objectives and actions in primary health care, relevant to health promotion and professional and autonomous care. We registered 24 phytotherapy programs introduced and developed in Brazilian states and municipalities ( Table 1 ), 13 studies on isolated actions developed by health professionals in the context of primary care services ( Table 2 ) and 16 studies on the acceptance and use/prescription of medicinal plants and phytotherapy by health professionals in primary health care services ( Table 3 ). The studies used various methods. Case studies and experiment reports were the principle methods used to describe and analyze the introduction and development of phytotherapy programs ( Table 1 ), while ethnographic and ethnobotanical studies and quali-quantitative research were used to analyze actions and acceptance of medicinal plant use by health care professional in primary care services ( Tables 2 and 3 ).

The studies on phytotherapy programs ( Table 1 ) and actions ( Table 2 ) reported that the intregration of phytotherapeutics and medicinal plants in primary health care improved access to other therapeutic options besides combined medicines, 16 , 17 , 24 , 27 , 29 , 37 , 41 they consolidated the implementation of public policies, 25 , 35 local development 1 0, 33 and promoted the revival of the population´s traditional knowledge. 4 , 10 , 16 , 24 , 29 , 3 7 , 41 Additionally, this integration prompted health professionals to organize educational health 10 , 17 , 24 , 27 , 33 , 37 , 40 , 43 and environmental 16 , 37 actions, as well as cross-sectoral actions 10 , 12 , 16 , 17 , 20 , 24 , 33 , 35 , 3 8 , 41 (in partnership with agriculture, education, environment) and extension and research actions with universities. 16 , 20 , 41 Some studies pointed out obstacles in consolidating phytotherapy actions and programs in health services, including the lack of strategy for registration and accompaniment in clinical use (to produce clinical evidence), 17 , 33 low investment in the study of Brazilian medicinal plants, 15 , 16 , 29 , 33 , 37 , 41 training and qualification deficits among human resources, 2 , 3 , 7 , 10 , 13 - 16 , 20 - 22 , 29 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 4 0, 43 and lack of human resources. 27 , 35 They also cited the lack of financial resources and management support 10 , 12 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 22 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 35 , 37 for organizing work spaces and purchasing the equipment and plant supplies required to offer quality phytotherapeutics and medicinal plants in sufficient quantities to meet the demand of the population. 10 , 23 , 28 , 34 , 35

The studies into the acceptance of phytotherapy by health professionals in primary health care services ( Table 3 ) discovered problems relating to the prescription/orientation of medicinal and phytotherapeutic plants in clinical practice among health team doctors, nurses and dentists. They also cited strategies for training health professionals through their everyday professional practice.

The absence of technical-practical training relating to phytotherapy during academic/professional development, which in part reflects the reality of national university teaching, 15 , 22 , 36 , 43 was considered the main obstacle in prescribing phytotheraphy in primary services and advising users on its application. 2 , 3 , 7 , 10 , 13 - 16 , 20 - 22 , 29 , 33 , 3 6 , 38 , 40 , 43 The prescription of phytotherapics and medicinal plants by health professionals could therefore be encouraged through a continuous and long-term education process for professionals, as part of health teams’ daily work routine. 7 , 36 , 43 Trained professionals would thereby be able to recognize those medicinal/phytotherapeutic plants most commonly used by their patients 3 , 7 , 13 , 36 and advise them accordingly. The identification of local therapeutic practices and resources could contribute to the development of adequate clinical communication strategies between professionals and users, 1 , 3 , 16 , 25 avoiding inadequate practices that lead to irrational use, belief in media propaganda, 11 clinical errors and lack of adhesion to treatment. 3 Further to this, it was reported that the integration of medicinal plant actions brings together professionals using medicinal plants in different contexts, who interact with primary health care services through dialogue with users and communities. 4 , 15 , 36 The integration of phytotherapy would presuppose the user’s central role and joint responsibility in the professional-patient dialogue. 1 , 3 - 5

DISCUSSION

Although the present article has not undertaken an exhaustive investigation of the pool of resources available for studies of this nature, it may be taken as a first attempt at scientific production in the area. The available resources in the Lilacs, SciELO and Thesis Portal Capes databases proved valuable to the study, and will also facilitate further studies given their intense use of information technology.

Due to the small number of publications (53 studies), under-represented in the 350 Brazilian municipalities that offer phytotherapy in primary health services in Brazil, it was not possible to discuss existing trends, seasonality and significance in the output on the topic. However, the scientific output on phytotherapy in primary health care services appears to be increasing.

It is notable that in Brazil, the country with the greatest biodiversity in the world, continental land area, cultural richness and medicinal plant knowledge, 6 originating from its three main ethnic groups (Indigenous, African and European), the primary health care field and Unified Health System (SUS) have so few registered experiments involving medicinal plant actions available in scientific literature at the end of the first decade of the 21st century.

With regards to the limited literature, and considering the potential of phytotherapy in health care and promotion, we have formed some hypotheses. In addition to the fact that actions have been under-reported, it is likely that there has been little academic interest in the field, resulting in a relatively poor body of scientific literature in relation to the greater number and diversity of trials involving medicinal plants in primary health care. This could also be linked to the low level of government and scientific support in instigating dedicated research in the field. Given the significant potential of the field and associated knowledge and technology, 46 it may be argued that there has been some wastage during the trials within primary care services, in expansion via the Estratégia Saúde da Família (ESF – Family Health Strategy).

Another theory is that the field of medicinal plants has been undervalued in Brazil 20 due to the widely held belief that treatment should be focused on chemotherapy. Medicinal plant use is seen a relic of an underdeveloped, primitive and archaic era, and not as part of a possible future involving new (and paradoxically ancient) sustainable technology, open to more complex ways of understanding how plants affect human beings. Even the paradigm based on isolating active ingredients is controlled more efficiently through traditional plant use, making Brazil´s pioneering potential indisputable.

Another possible hypothesis for the scarcity of literature on the topic is the lack of integration between different areas of knowledge (chemistry, biochemistry, pharmacology, botany, pharmaceutical technology among others), necessary to obtain an effective result in the research and development of new phytotherapeutics. 46 Additionally, the fact that most journals published on the topic have been given the lowest quality rating (Qualis) for Collective Health may indicate that the subject is underappreciated, or not prioritized in the editorial lines of scientific journals in the area of collective health. 20 , 46

The scientific relevance of developing research into phytotherapeutic programs in Brazil is linked to the importance of building knowledge in an area that is still underdeveloped, with few researchers in Brazil or in collective health. Moreover, the integration of phytotherapeutic and medicinal plant use could improve access to other therapeutic care options, and promote liaison and dialogue between different skills areas, values and practices that, though not scientifically or administratively regulated by the market, are still found in communities and are therefore ‘important for the promotion of health and institutional and autonomous care. 3 , 25 The practical and social relevance of the topic is linked to the need to raise awareness amongst managers, health professionals and researchers of the importance of the topic and its implications for discursive, supportive, participative, interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral practices in a way that is committed to competent and culturally appropriate 25 primary health care, as part of the health promotion discourse. 3

Footnotes

Article based on the doctoral thesis of Antonio GD, entitled: “Fitoterapia na Atenção primária à saúde: interação de saberes e práticas de cuidado em saúde”, presented to the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina , in 2013.

Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Práticas integrativas e complementares: plantas medicinais e fitoterapia na Atenção Básica/Ministério da Saúde. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde, 2012.156 p:il. (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos) (Cadernos de Atenção Básica; n. 31). [cited 2014 Mar]. Available from: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/publicacoes/geral/miolo_CAP_31.pdf

Ministério da Saúde, Gabinete do Ministro. Portaria n° 971, de 3 de maio de 2006. Aprova a Política Nacional de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares (PNPIC) no Sistema Único de Saúde. Brasília (DF); 2006 [cited 2014 Mar 22]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2006/prt0971_03_05_2006.html

Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. Decreto n° 5.813, 22 de junho de 2006. Aprova a Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Fitoterápicos e dá outras providências. Brasília (DF); 2006 [cited 2014 Mar 22]. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004-2006/2006/Decreto/D5813.htm

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvim NAT, Cabral IE. A aplicabilidade das plantas medicinais por enfermeiras no espaço do cuidado institucional. Esc Anna Nery. 2001;5(2):201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvim NAT, Ferreira MA, Cabral IE, Almeida AJ., Filho The use of medicinal plants as a therapeutical resource: from the influences of the professional formation to the ethical and legal implications of its applicability as an extension of nursing care practice. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2006;14(3):316–323. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692006000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonio GD, Tesser DC, Moretti-Pires RO. Interface. 46. Vol. 17. Botucatu: 2013. Contribuições das plantas medicinais para o cuidado e a promoção da saúde na atenção primária à saúde; pp. 615–633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araújo MAM. Interface. 7. Vol. 4. Botucatu: 2000. Bactris e quebras-pedras; pp. 103–110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badke MR, Budó MLD, Silva FM, Ressel LB. Plantas medicinais: o saber sustentado na prática do cotidiano popular. Esc. Anna Nery. 2011;15(1):132–139. doi: 10.1590/S1414-81452011000100019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreiro EJ, Bolzani VS. Biodiversidade: fonte potencial para a descoberta de fármacos. Quim Nova. 2009;32(3):679–688. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422009000300012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastos RAA, Lopes AMC. A fitoterapia na rede básica de saúde: o olhar da enfermagem. Rev Bras Cienc Saude. 2010;14(2):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasileiro BG, Pizziolo VR, Matos DS, Germano AM, Jamal CM. Plantas medicinais utilizadas pela população atendida no “Programa de Saúde da Família”, Governador Valadares, MG, Brasil. Rev Bras Cienc Farm. 2008;44(4):629–636. doi: 10.1590/S1516-93322008000400009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruning MCR, Mosegui GBG, Vianna CMM. A utilização da fitoterapia e de plantas medicinais em unidades básicas de saúde nos municípios de Cascavel e Foz do Iguaçu - Paraná: a visão dos profissionais de saúde. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2012;17(10):2675–2685. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232012001000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carneiro SMO, Pontes LML, Gomes VAF, Filho, Guimarães MA. Da planta ao medicamento: experiência da utilização da fitoterapia na atenção primária à saúde no Município de Itapipoca/CE. Divulg Saude Debate. 2004;(30):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz PLB, Sampaio SF, Gomes TLCS. O uso de práticas complementares por uma equipe de Saúde da Família e sua população. Rev APS. 2012;15(4):486–495. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diniz RC. Programa Municipal de Fitoterapia no município de Londrina, Paraná (PR) Divulg Saude Debate. 2006;(34):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fontanella F, Speck FP, Piovezan AP, Kulkamp IC. Conhecimento, acesso e aceitação das práticas integrativas e complementares em saúde por uma comunidade usuária do Sistema Único de Saúde na cidade de Tubarão/SC. ACM Arq Catarin Med. 2007;36(2):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontenele RP, Sousa DMP, Carvalho ALM, Oliveira FA. Fitoterapia na Atenção Básica: olhares dos gestores e profissionais da Estratégia Saúde da Família de Teresina (PI), Brasil. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2013;18(8):2385–2394. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232013000800023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.França WFA, Marques MMMR, Lira KDL, Higino ME. Terapêutica com plantas medicinais nas doenças bucais: a percepção dos profissionais no Programa de Saúde da Família do Recife. Odontol Clin Cient. 2007;6(3):233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graça C. Treze anos de fitoterapia em Curitiba. Divulg Saude Debate. 2004;(30):36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guimarães J, Vieira LA, Medeiros JC. Programa fitoterápico Farmácia Viva no SUS-Betim-Minas Gerais. Divulg Saude Debate. 2006;(36):41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guizardi FL, Pinheiro R. Interface. 24. Vol. 12. Botucatu: 2008. Novas práticas sociais na constituição do direito à saúde: a experiência de um movimento fitoterápico comunitário; pp. 109–122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein T, Longhini R, Bruschi ML, Mello JCP. Fitoterápicos: um mercado promissor. Rev Cienc Farm Basica Apl. 2009;30(3):241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leite SN, Schor N. Fitoterapia no Serviço de Saúde: significados para clientes e profissionais de saúde. Saude Debate. 2005;29(69):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima JF, Júnior, Dimenstein M. A fitoterapia na saúde pública em Natal/RN: visão do odontólogo. Saude Rev. 2006;8(19):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machado DC, Czermainski SBC, Lopes EC. Percepções de coordenadores de unidades de saúde sobre fitoterapia e outras práticas integrativas e complementares. Saude Debate. 2012;36(95):615–623. doi: 10.1590/S0103-11042012000400013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marques LAM, Vale FVVR, Nogueira VAS, Mialhe FL, Silva LC. Atenção farmacêutica e práticas integrativas e complementares no SUS: conhecimento e aceitação por parte da população sãojoanense. Physis. 2011;21(2):663–674. doi: 10.1590/S0103-73312011000200017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matos FJA. O projeto Farmácias-Vivas e a fitoterapia no nordeste do Brasil. Rev Cienc Agrovet. 2006;5(1):24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menéndez EL. Modelos de atención de los padecimientos: de exclusiones teóricas y articulaciones prácticas. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2003;8(1):185–207. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232003000100014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michiles E. Diagnóstico situacional dos serviços de fitoterapia no Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2004;14(Supl):16–19. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2004000300007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagai SC, Queirós MS. Medicina complementar e alternativa na rede básica de serviços de saúde: uma aproximação qualitativa. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2011;16(3):1793–1800. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negrelle RRB, Tomazzoni MI, Ceccon MF, Valente TP. Estudo etnobotânico junto à Unidade Saúde da Família Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes: subsídios para o estabelecimento de programa de fitoterápicos na rede básica de saúde do município de Cascavel (Paraná) Rev Bras Plantas Med. 2007;9(3):6–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogava SEN, Pinto MTC, Kikuchi T, Menegueti VAF, Martins DBC, Coelho SAD, et al. Implantação do programa de fitoterapia “Verde Vida” na Secretaria de Saúde de Maringá (2000-2003) Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2003;13(Supl. 1):58–62. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2003000300022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira MJR, Simões MJS, Sassi CRR. Fitoterapia no Sistema de Saúde Pública (SUS) no estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Rev Bras Plantas Med. 2006;8(2):39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otani MAP, Barros NF. A Medicina Integrativa e a construção de um novo modelo na saúde. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2011;16(3):1801–1811. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paranaguá TTB, Bezerra ALQ, Souza MA, Siqueira KM. As práticas integrativas na Estratégia Saúde da Família: visão dos agentes comunitários de saúde. Rev Enferm UERJ. 2009;17(1):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pires AM, Borella JC, Raya LC. Práticas alternativas de saúde na atenção básica na rede SUS de Ribeirão Preto/SP. Divulg Saude Debate. 2004;(30):56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pontes RMF, Monteiro PS, Rodrigues MCS. O uso de plantas medicinais no cuidado de crianças atendidas em um centro de saúde do Distrito Federal. Comun Cienc Saude. 2006;17(2):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reis MCP, Leda PHO, Pereira MTCL, Tunala EAM. Experiência na implantação do Programa de Fitoterapia do Município do Rio de Janeiro. Divulg Saude Debate. 2004;(30):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosa C, Câmara SG, Béria JU. Representações e intenção de uso da fitoterapia na atenção básica à saúde. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2011;16(1):311–318. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011000100033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacramento HT. O programa de fitoterapia do Município de Vitória (ES) Divulg Saude Debate. 2004;(30):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampaio LA, Oliveira DR, Kerntopf MR, Brito FE, Júnior, Menezes IRA. Percepção dos enfermeiros da estratégia saúde da família sobre o uso da fitoterapia. REME Rev Min Enferm. 2013;17(1):76–84. doi: 10.5935/1415-2762.20130007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos FAS, Sousa IMC, Gurgel IGD, Bezerra AFB, Barros NF. Política de práticas integrativas em Recife: análise da participação dos atores. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;45(6):1154–1159. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011000600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos MC, Tesser CD. Um método para implantação e promoção de acesso às práticas integrativas e complementares na Atenção Primária à Saúde. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2011;17(11):3011–3024. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232012001100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva MIG, Gondim APS, Nunes IFS, Sousa FCF. Utilização de fitoterápicos nas unidades básicas de atenção à saúde da família no município de Maracanaú (CE) Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2006;16(4):455–462. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2006000400003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taufner CF, Ferraço EB, Ribeiro LF. Uso de plantas medicinais como alternativa fitoterápica nas unidades de saúde pública de Santa Teresa e Marilândia, ES. [2014];Natureza on line. 2006 4(1):30–39. http://www.naturezaonline.com.br/natureza/conteudo/pdf/Medicinais_STer_Mari.pdf Internet. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiago SCS, Tesser CD. Percepção de médicos e enfermeiros da Estratégia de Saúde da Família sobre terapias complementares. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(2):249–257. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102011005000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomazzoni MI, Negrelle RRB, Centa ML. Fitoterapia popular: a busca instrumental enquanto prática terapeuta. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2006;15(1):115–121. doi: 10.1590/S0104-07072006000100014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viegas C, Jr, Bolzani VS, Barreiro EJ. Os produtos naturais e a química moderna. Quím Nova. 2006;29(2):326–337. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422006000200025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villas Bôas GK, Gadelha CAG. Oportunidades na indústria de medicamentos e a lógica do desenvolvimento local baseado nos biomas brasileiros: bases para a discussão de uma política nacional. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(6):1463–1471. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2007000600021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]