Abstract

This study examined mother–adolescent conflict as a mediator of longitudinal reciprocal relations between adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms and maternal psychological control. Motivated by family systems theory and the transactions that occur between individual and dyadic levels of the family system, we examined the connections among these variables during a developmental period when children and parents experience significant psychosocial changes. Three years of self-report data were collected from 168 mother–adolescent dyads, beginning when the adolescents (55.4% girls) were in 6th grade. Models were tested using longitudinal path analysis. Results indicated that the connection between adolescent aggression (and depressive symptoms) and maternal psychological control was best characterized as adolescent-driven, indirect, and mediated by mother–adolescent conflict; there were no indications of parent-driven indirect effects. That is, prior adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms were associated with increased conflict. In turn, conflict was associated with increased psychological control. Within our mediation models, reciprocal direct effects between both problem behaviors and conflict and between conflict and psychological control were also found. Additionally, exploratory analyses regarding the role of adolescent gender as a moderator of variable relations were conducted. These analyses revealed no gender-related patterns of moderation, whether moderated mediation or specific path tests for moderation were considered. This study corroborates prior research finding support for child effects on parenting behaviors during early adolescence.

Keywords: psychological control, aggression, depressive symptoms, mother–adolescent conflict, longitudinal

Parental psychological control, defined as exerting intrusive and covert control through means such as love withdrawal, guilt induction, and instilling anxiety, has been consistently associated with externalizing and internalizing problems among children and adolescents (for review, see Barber, 2002). Psychological control is theorized to exert its destructive effects by undermining adolescents’ ability to function autonomously (Barber & Harmon, 2002). More broadly, psychological control can be framed as parenting that hampers the development of adolescent self-regulation of behavior and affect. Foundational theories of psychological control conceptualized this dimension of parenting as parent-driven and stimulated, in large part, by parental psychological disturbances and associated unwillingness to accept child individuation (Barber, 2002; Schaefer, 1965). Contemporary perspectives have broadened the consideration of predictors of psychological control to include factors beyond the intrapsychic vulnerabilities of parents, such as environmental pressures and child characteristics (e.g., Barber, 1996; Grolnick, 2003; see also Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010).

As part of the consideration of multiple determinants of psychological control, reciprocal connections between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors have been posited (e.g., Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005). According to this perspective, while adolescents may respond to intrusive parenting with dysregulation of affect and behavior, parents may respond to such maladjustment with intrusive control (e.g., Pettit, Laird, Dodge, Bates, & Criss, 2001). Thus, while the effects of psychological control on adolescents have been consistently acknowledged and remain a focus in the literature, more recent longitudinal efforts reveal that adolescent characteristics contribute to psychological control as well (e.g., Albrecht, Galambos, & Jansson, 2007; Barber et al., 2005; Loukas, 2009; Rogers, Buchanan, & Winchell, 2003; Soenens, Luyckx, Vansteenkiste, Duriez, & Goossens, 2008).

The consideration of adolescent influences on parental psychological control derives from developmental theory positing that children actively influence parental behavior (e.g., Belsky, 1984; Kuczynski & Parkin, 2007; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). The examination of adolescent-driven effects is also consistent with conceptual models of family transformation during adolescence. According to such perspectives, adolescents are described as catalysts for change in parent-child relations (Kidwell, Fischer, Dunham, & Baranowski, 1983). For example, early adolescents appear to gain influence during family interactions, as parents yield more to their adolescents’ increasing assertions (for review, see Silverberg, Tennenbaum, & Jacob, 1992). Most relevant to the present study, such changes in parent–adolescent interactions may contribute to a context in which there are heightened adolescent effects on parents (Lytton, 1990; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Therefore, adolescent behavior may begin to have a stronger influence on parenting practices within the family.

Based on theory specifying both parent and adolescent contributions to parenting, several longitudinal studies have found reciprocal relations between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors in externalizing and internalizing domains (e.g., Barber et al., 2005; Rogers et al., 2003; Soenens et al., 2008). For instance, Soenens et al. (2008) found that psychological control and adolescent depressive symptoms were reciprocally related over two of three time points in a sample of mid and late adolescents. Most relevant to the present study, maternal psychological control predicted increased adolescent depressive symptoms, whereas adolescent depressive symptoms predicted increased maternal psychological control. Barber et al. (2005) found similar reciprocal relations between psychological control and antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms in a longitudinal study of young adolescents. More specifically, maternal psychological control predicted adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms from Year 1 to Year 2, whereas adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms predicted maternal psychological control from Year 2 to Year 3.

Contrary to theory specifying reciprocal effects, at least two prior studies investigating relations between psychological control and adolescent behavior have found support only for an adolescent direction of effects (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2007; Loukas, 2009). For instance, Albrecht et al. (2007) found that adolescents’ prior physical aggression and internalizing problems predicted increases in maternal psychological control 2 years later; however, prior psychological control did not predict subsequent aggression or internalizing. Similarly, Loukas (2009) found that adolescent depressive symptoms predicted increased maternal psychological control 1 year later, while prior psychological control did not predict subsequent depressive symptoms. Such results are in accordance with the viewpoint that young adolescents may have particularly strong effects on the parenting that they receive (e.g., Lytton, 1990; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). However, both Albrecht et al. and Loukas considered only adolescent reports of parenting and problem behaviors and also assessed relations over only two time points. It is possible that both parent and adolescent effects might be detected if parent reports were also considered and if relations were assessed over longer periods of time.

The current study extends the literature by utilizing both mother and adolescent reports and by assessing model relations over three time points. Consistent with prior research focused on associations between psychological control and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2007; Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005), we measured adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms in separate models. Although we expected both problem behaviors to operate similarly, separate analyses of aggression and depressive symptoms, rather than analysis of a problem behavior composite, permitted better interpretation of model relations. Additionally, to our knowledge, no prior studies have examined process-oriented models, focusing instead on direct relations between psychological control and adolescent externalizing and internalizing behaviors (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2007; Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005; Conger, Conger, & Scaramella, 1997; Loukas, 2009; Rogers et al., 2003; Soenens et al., 2008; Wang, Pomerantz, & Chen, 2007). Although direct effects are reasonable, it is possible that the reciprocal relations between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors are mediated by other individual or dyadic variables. In particular, we contend that mother–adolescent conflict may mediate connections between psychological control and adolescent externalizing and internalizing behaviors.

Our decision to specify mother–adolescent conflict as a mediator was motivated by family systems theory (e.g., Cox & Paley, 1997), and in particular conceptual descriptions of transactions between individual and dyadic levels of the family system (e.g., Kuczynski & Parkin, 2007). According to this perspective, problems in one family subsystem, such as problems in parenting, are likely to diminish family members’ individual functioning (Kuczynski & Parkin, 2007). At the same time, individual members’ problems are likely to affect dyadic relations, including the occurrence and expression of conflict (e.g., Patterson, 1982). Although is it somewhat difficult to express systems transactions in the linear models afforded by mediation analyses, dyadic properties such as conflict often are posited as mechanisms by which functioning in one family subsystem affects functioning in another (e.g., Patterson, 1982). Consistent with this well-established conceptual viewpoint, we hypothesized that mother–adolescent conflict would function as a mediating mechanism, accounting for relations over time between psychological control and adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms.

In further support of our mediation hypothesis, several cross-sectional studies have revealed a positive correlation between mother–adolescent conflict and maternal psychological control (Forehand & Nousiainen, 1993; Sturge-Apple, Gondoli, Bonds, & Salem, 2003; Yau & Smetana, 1996). In one interpretation of this relation, psychological control might foster parent–adolescent conflict. Parental intrusive and coercive behaviors are inappropriate at any age but may be especially pernicious at the transition to adolescence, when children are attempting to gain autonomy and progress toward independence (Barber, 1996; Silverberg & Gondoli, 1996). Therefore, intrusive and coercive parental control is likely to provoke adolescent resistance and associated parent–adolescent conflict (Smetana & Gaines, 1999; Sturge-Apple et al., 2003; Yau & Smetana, 1996). Alternatively, parent–adolescent conflict might lead to greater parental psychological control. Mothers are more likely to use psychological control when stressed by parenting difficulties, including difficulties caused by aversive parent-child interactions (e.g., Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997; Grolnick, 2003). Thus, mother–adolescent conflict may provoke a mother to use psychological control, in an effort to dampen conflict and manage her adolescent’s behavior (Loukas, 2009; Rogers et al., 2003). Of course, it is possible that both directions of effects may occur; that is, reciprocal connections may exist between psychological control and conflict, a possibility that we examine in the present study.

In addition to being associated with greater parental psychological control, parent–adolescent conflict is also positively correlated with adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems (e.g., Greenberger & Chen, 1996; Vandewater & Lansford, 2005). In interpreting these relations, it is possible that conflict may lead to adolescent problem behaviors. Conflict may set the stage for aggressive behaviors and may also result in depressed feelings (Patterson, 1982; Vandewater & Lansford, 2005). Alternatively, adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems may foster greater parent–adolescent conflict. In support of this adolescent-driven perspective, Gerard, Krishnakumar, and Buehler (2006) examined the associations among marital conflict, parent-youth conflict, and youth problem behaviors over a 5-year period, beginning when the preadolescents were 5–11 years old. Most relevant to the present study, preadolescents’ prior externalizing behaviors at Time 1 predicted subsequent mother–adolescent conflict at Time 2. Adolescents who exhibit depressive symptoms also elicit distressed reactions from their mothers (Sheeber & Sorensen, 1998), and it is reasonable to suggest that parent–adolescent conflict may result from parents’ responses to depressed adolescents’ negative affect and difficult behavior (see also Lindahl & Markman, 1990). Again, reciprocal connections may occur between dimensions of adolescent problem behaviors and parent–adolescent conflict, potential relations that we examine with our longitudinal data.

Adolescent Gender as a Moderator

We also examined adolescent gender as a potential moderator of the longitudinal associations within our models. Some evidence suggests that parent–adolescent relationship quality is more strongly associated with girls’ than with boys’ well-being (Lead-beater, Kuperminc, Blatt, & Hertzog, 1999), and it has also been suggested that parents might be more negatively affected by girls’ externalizing problems because such behavior is more aberrant for girls than for boys (see Pettit et al., 2001). Therefore, it is possible that stronger relations among psychological control, conflict, and problem behaviors might be found for girls than for boys. To date, however, the evidence regarding gender as a moderator of such relations has been mixed, sometimes even within the same study.

For instance, Conger et al. (1997) detected stronger relations between psychological control and adolescent adjustment among girls than boys when contemporaneous associations were examined. When longitudinal patterns of relations were examined, however, boys were more affected by psychological control than were girls. Soenens et al. (2008) also reported that prior maternal psychological control predicted adolescent boys’ but not girls’ depression over time. In contrast, Pettit et al. (2001) reported that prior maternal psychological control was more highly associated with girls’ than with boys’ subsequent internalizing problems and delinquency. Furthermore, other notable longitudinal studies have found no adolescent gender differences in the patterns of relations between psychological control and internalizing or externalizing problems (Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005; Gerard et al., 2006; Loukas, 2009).

In sum, the evidence regarding adolescent gender as a moderator is inconsistent. However, explorations of gender effects occur relatively frequently in the literature, and we were requested during the review process to examine the potential moderating role of adolescent gender in our data. Given that our primary interest was to test reciprocal indirect effects, we examined whether the mediation paths in our models were moderated by adolescent gender. More specifically, we tested whether mother–adolescent conflict served as a mediator of reciprocal relations between adolescent problem behaviors and maternal psychological control only (or more strongly) for male or female adolescents.

Aims of the Present Study

Although emerging research suggests that adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems and parental psychological control are reciprocally related (e.g., Barber et al., 2005; Soenens et al., 2008), additional research that considers both adolescent and parent reports and multiple time periods is warranted. In addition, variables that may mediate such reciprocal connections have not been considered. Consistent with family systems theory and conceptual models of family relations during adolescence, we hypothesized that mother–adolescent conflict would mediate the longitudinal, reciprocal connections between adolescent problems and maternal psychological control. Both directions of indirect effects, relatively adolescent-driven and relatively mother-driven, were examined simultaneously in longitudinal models.

Method

Participants

Data were collected annually from 168 mother–adolescent dyads as the adolescents completed sixth through eighth grade. At the sixth grade assessment, the adolescents (75 boys, 93 girls) were between the ages of 11 and 13 (M = 11.66, SD = 0.51). Most identified themselves as European American (95.8%); fewer identified themselves as African American (1.8%), Latina/o (1.2%), Asian American (0.6%), or multiethnic (0.6%). Of the mothers participating in the current study, 90.4% indicated that they were married and living with their spouse, 7.2% were divorced, and 2.4% were separated. Mothers reported having an average of 2.5 children in their families (SD = 0.96). The mothers were generally well-educated and middle-class: Mothers had completed, on average, 2.5 years of education after receiving their high school diplomas, 79% worked full- or part-time outside the home, and the annual household income per family ranged from U.S.$8,892 to U.S.$450,000 with a mean annual income of U.S.$86,348 (SD = U.S.$64,666).

The present data were collected as part of a larger study focusing on mother and child outcomes during the transition to adolescence. The recruitment and procedures of this 5-year longitudinal study have been described previously (Grundy, Gondoli, & Blodgett-Salafia, 2010). Briefly, initial contact letters were distributed to fourth grade students through primary schools in a medium-sized, Midwestern city. The letter briefly described the study and instructed mothers of fourth graders to call the research office if they were interested in participating. To control for prior parenting experience, mother-child dyads were eligible if the fourth grader was the oldest child in the family. In addition, dyads were eligible if the mother was either currently married to the child’s father and had never been divorced or was currently divorced. Remarried families were not enrolled because they reflected varied patterns of marital transitions and co-residence of older and younger children.

One hundred eighty-one (91%) of the eligible dyads completed the study during the initial fourth grade assessments. After attrition, 168 dyads’ data were available for analysis in the present study. These dyads included 159 with complete data and nine with random missing data that were estimated; dyads with missing data participated in at least one assessment during sixth to eighth grade. These particular grades were selected for the present analyses for both conceptual and pragmatic reasons. First, these grades are similar to those included by prior studies illustrating reciprocal connections between adolescent problem behaviors and parenting (e.g., Barber et al., 2005; Rogers et al., 2003). In addition, all model variables were available during the sixth–eighth grade assessments. According to t test, analysis of variance, and chi-square procedures, the 168 mother–adolescent dyads included in the present analyses did not differ on any of the Time 1 demographic variables from the 13 dyads who had completed Year 1 of the larger study but were not included the present analyses.

Procedure

Each year, mothers and their children visited a university research laboratory for 2 hr to separately and independently complete questionnaire packets. As compensation, each dyad was paid U.S.$50 at the sixth grade assessment, with an increase in this rate by U.S.$10 for each subsequent year; by the eighth grade assessment, each dyad received U.S.$70.

Measures

All measures used in this study were derived from questionnaires administered in identical forms when the adolescents were in sixth–eighth grade.

Adolescent aggression

Adolescents’ reports of their aggressive behaviors were assessed with the Aggression subscale of the Youth Self-Report for Ages 11–18 (YSR/11–18; Achenbach, 1991b). Maternal perceptions of their adolescents’ aggressive behaviors were measured with parallel items of the Aggression subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991a). The YSR and CBCL Aggression subscales consist of 20 items that assess overt and covert aggression, including behaviors such as jealousy and stubbornness. Items were rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true), with higher scores indicating greater aggressive behavior. Sample items included “I argue a lot” and “My child has a hot temper.” Across the 3 years of data collection, internal reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranged from .82 to .84 for adolescent reports and .85 to .88 for maternal reports.

Adolescent depressive symptoms

Adolescent and maternal reports of adolescent depressive symptoms were assessed using corresponding child and parent versions of the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Cole, Gondoli, & Peeke, 1998; Kovacs, 1985). For the present study, the original 27-item scale was reduced to 26 items due to the elimination of a controversial suicide item. Adolescents and mothers were asked to select a statement that best described themselves or their adolescent from three sentences listed in order of increasing severity (scored from 0 to 2), with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. For example, the statement choices from one adolescent item were “I am sad once in a while,” “I am sad many times,” “I am sad all the time.” Across the 3 years of data collection, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .81 to .84 for adolescent reports and .77 to .83 for maternal reports.

Mother–child conflict

Negative mother–adolescent conflict behavior was assessed by the Dyadic Behavior subscale of the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Robin & Foster, 1989; Sturge-Apple et al., 2003). Adolescents and mothers completed parallel versions of the subscale; responses were on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (really false) to 4 (really true). Higher scores indicated greater negative conflict behavior. Sample items included “My mom and I have big arguments about little things” and “My child and I speak to each other only when we have to.” Across the 3 years of data collection, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .90 to .92 for adolescent reports and .89 to .91 for maternal reports.

Maternal psychological control

Maternal psychological control was measured with parallel versions of the Psychological Control Scale—Youth Self-Report (PCS–YSR; Barber, 1996), an eight-item scale that assessed maternal psychological controlling behaviors such as love withdrawal, invalidation of feelings, constraining verbal expression, and personal verbal attack. Adolescents’ and mothers’ reports of maternal psychological control were assessed with parallel items on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always), and items were scored such that higher scores indicated greater psychological control. Sample items included “My mom is always trying to change how I think or feel about things” and “My mom will avoid looking at me when I have disappointed her.” Across the 3 years of data collection, Cronach’s alpha ranged from .81 to .85 for adolescent reports and .76 to .78 for maternal reports.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are displayed in Table 1. Correlations among the variables were statistically significant and in the expected directions. In addition, mothers’ and adolescents’ reports on the study variables were significantly correlated with the exception of psychological control in seventh and eighth grades (see Table 1). We also correlated adolescent gender with all study variables and examined mean differences on the variables by adolescent gender. Results of these exploratory analyses revealed that gender was uncorrelated with all study variables, for both adolescent reports (rs ranged from −.01 to .09, ps > .05) and maternal reports (rs ranged from −.02 to −.13, ps > .05). Furthermore, t tests indicated no gender mean differences in any variables for adolescent reports (ps > .05) or maternal reports (ps > .05).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations of Study Variables (N = 168).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adol. aggression in 6th grade | .40** | .68** | .55** | .50** | .35** | .36** | .51** | .48** | .37** | .38** | .34** | .30** |

| 2. Adol. aggression in 7th grade | .75** | .36** | .70** | .34** | .53** | .45** | .44** | .54** | .42** | .35** | .40** | .36** |

| 3. Adol. aggression in 8th grade | .69** | .80** | .36** | .33** | .41** | .56** | .34** | .38** | .39** | .30** | .24** | .36** |

| 4. Adol. depress. sympt. in 6th grade | .51** | .43** | .41** | .33** | .60** | .56** | .44** | .43** | .43** | .34** | .26** | .38** |

| 5. Adol. depress. sympt. in 7th grade | .44** | .49** | .48** | .77** | .36** | .73** | .45** | .47** | .39** | .34** | .35** | .37** |

| 6. Adol. depress. sympt. in 8th grade | .44** | .45** | .45** | .69** | .70** | .31** | .42** | .43** | .48** | .29** | .28** | .43** |

| 7. Mother–adol. conflict in 6th grade | .53** | .51** | .43** | .41** | .38** | .39** | .41** | .73** | .59** | .72** | .58** | .56** |

| 8. Mother–adol. conflict in 7th grade | .52** | .68** | .54** | .41** | .46** | .35** | .67** | .41** | .73** | .54** | .67** | .59** |

| 9. Mother–adol. conflict in 8th grade | .55** | .62** | .61** | .35** | .40** | .41** | .69** | .74** | .33** | .46** | .54** | .70** |

| 10. Mother psych. control in 6th grade | .38** | .37** | .36** | .25** | .33** | .21** | .42** | .46** | .40** | .19* | .70** | .64** |

| 11. Mother psych. control in 7th grade | .39** | .44** | .34** | .27** | .31** | .18* | .40** | .52** | .39** | .69** | .13 | .68** |

| 12. Mother psych. control in 8th grade | .40** | .43** | .45** | .21** | .20* | .16* | .45** | .45* | .45** | .61** | .64** | .13 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Adolescents | ||||||||||||

| M | 7.14 | 7.93 | 8.26 | 3.66 | 3.96 | 4.72 | 33.70 | 35.20 | 34.65 | 5.05 | 6.20 | 5.99 |

| SD | 4.46 | 4.73 | 5.10 | 4.00 | 4.39 | 4.72 | 8.58 | 9.63 | 8.46 | 4.19 | 4.96 | 4.79 |

| Mothers | ||||||||||||

| M | 6.56 | 6.34 | 5.83 | 4.01 | 4.11 | 3.64 | 35.32 | 35.20 | 35.07 | 7.46 | 7.41 | 7.66 |

| SD | 4.99 | 5.59 | 4.96 | 4.34 | 4.15 | 3.79 | 8.55 | 8.23 | 7.87 | 3.20 | 3.14 | 3.24 |

Note. Adol. = adolescent; depress. sympt. = depressive symptoms; psych. control = psychological control. Correlations using adolescent reports appear above the diagonal, and correlations using maternal reports appear below the diagonal. Correlations between adolescent and maternal reports of the same construct appear directly on the diagonal in bold font. Sample sizes for correlations range from 162 to 167 due to pairwise deletion of missing data.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Plan of Model Testing

Longitudinal path analysis was used to examine relations among adolescent aggression or depressive symptoms, mother–adolescent conflict, and maternal psychological control. Adolescent- and mother-driven indirect effects were examined simultaneously in each model. Thus, adolescent aggression or depressive symptoms predicted conflict, which, in turn, predicted maternal psychological control, while psychological control predicted conflict, which, in turn, predicted aggression or depressive symptoms. To provide cross-informant replication, models were estimated first with adolescent reports on the variables and second with maternal reports on the variables, for a total of four models evaluated.

Consistent with recommendations for testing longitudinal mediation, we measured all variables in our models at all three time points and included all autoregressive paths (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Models were estimated using Mplus Version 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007), using the full information maximum-likelihood estimation procedure (FIML; Arbuckle, 1996) to accommodate missing data in nine of the 168 included dyads. To evaluate model fit, we examined the chi-square statistic, where nonsignificant p values (p > .05) indicate acceptable model fit; the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), in which scores above .95 suggest acceptable model fit; and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Steiger, 1990), in which values at or below .06 indicate acceptable fit. The significance of the indirect effect (ab) was determined by the PRODCLIN procedure (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007).

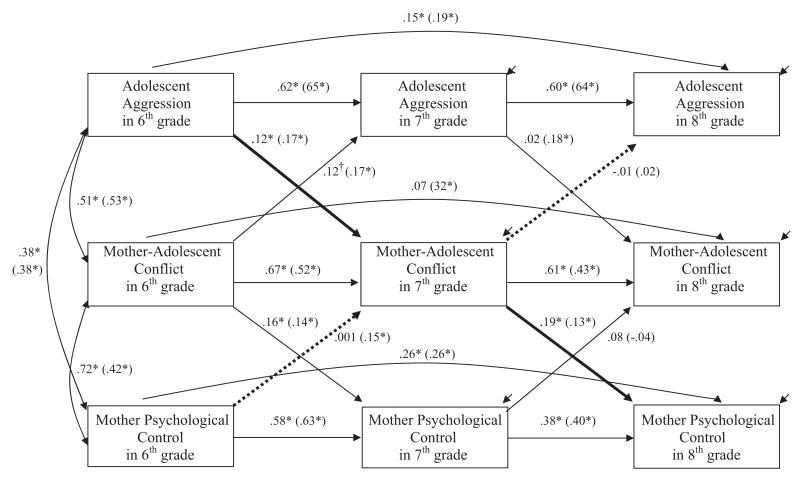

Adolescent Aggression, Mother–Adolescent Conflict, and Maternal Psychological Control

Our first hypothesized model examined whether mother–adolescent conflict mediated the potential reciprocal connections between adolescent aggression and maternal psychological control. To begin, adolescent reports were used to measure all variables in the model. The model fit the data well, χ2(10, N = 168) = 5.492, p = .856; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000 (see Figure 1). As depicted by the central downward paths in the model, adolescent aggression in sixth grade predicted higher levels of mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade. In turn, higher conflict in seventh grade predicted increased psychological control in eighth grade. The confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect of aggression on psychological control via mother–adolescent conflict at p = .05 was [.00173, .05603], indicating that this mediating path was significant. In contrast, maternal psychological control in sixth grade did not significantly predict mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade, nor did conflict in seventh grade predict adolescent aggression in eighth grade (see central upward paths in the model). Given these nonsignificant paths, there was no evidence that mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade mediated the relation between maternal psychological control in sixth grade and adolescent aggression in eighth grade.

Figure 1.

Indirect effects model, with adolescent report path coefficients outside of parentheses and maternal report path coefficients inside parentheses. N = 168 adolescents and mothers. Bolded solid lines indicate the tested adolescent-driven indirect path, and dashed lines indicate the mother-driven indirect path. Error variances at concurrent time points are correlated but not depicted for ease of presentation. †p 7lt; .10. * p < .05.

Our second model again estimated relations among aggression, conflict, and psychological control, this time using maternal reports on all variables. This model fit the data well, χ2(10, N = 168) = 16.487, p = .087; CFI = .993, RMSEA = .062 (see Figure 1). As depicted by the central downward paths in the model, adolescent aggression in sixth grade predicted higher levels of mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade. In turn, higher conflict in seventh grade predicted increased psychological control in eighth grade. The CI for the indirect effect of aggression on psychological control via mother–adolescent conflict at p = .05 was [.00012, .03420], indicating that this mediating path was significant. Examination of the connections between prior maternal psychological control and subsequent conflict and aggression yielded mixed findings. As depicted, maternal psychological control in sixth grade predicted greater mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade; however, mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade did not predict adolescent aggression in eighth grade (see central upward paths in the model). Given the nonsignificant path between mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade and adolescent aggression in eighth grade, there was no evidence for mediation.

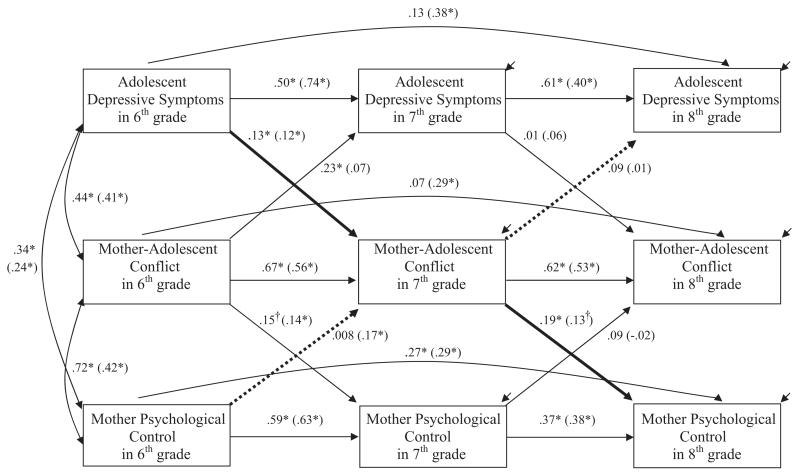

Adolescent Depressive Symptoms, Mother–Adolescent Conflict, and Maternal Psychological Control

Our third hypothesized model examined whether mother–adolescent conflict mediated the potential reciprocal relations between adolescent depressive symptoms and maternal psychological control. We began by using adolescent reports on all variables in the model. The model fit the data well, χ2(10, N = 168) = 8.487, p = .581; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000 (see Figure 2). As illustrated by the central downward paths in the model, adolescent depressive symptoms in sixth grade predicted higher levels of mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade. In turn, higher conflict in seventh grade predicted increased psychological control in eighth grade. The CI for the indirect effect of depressive symptoms on psychological control via mother–adolescent conflict at p = .05 was [.00432, .06629], indicating that this mediating path was significant. In contrast, maternal psychological control in sixth grade did not predict mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade, nor did conflict in seventh grade predict adolescent depressive symptoms in eighth grade (see central upward paths in the model). Given these nonsignificant paths, there was no evidence that mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade mediated the relation between prior maternal psychological control in sixth grade and subsequent adolescent depressive symptoms in eighth grade.

Figure 2.

Indirect effects model, with adolescent report path coefficients outside of parentheses and maternal report path coefficients inside parentheses. N = 168 adolescents and mothers. Bolded solid lines indicate the adolescent-driven indirect path, and dashed lines indicate the mother-driven indirect path. Error variances at concurrent time points are correlated but not depicted for ease of presentation. †p < .10. * p < .05.

Our fourth model again specified relations among depressive symptoms, conflict, and psychological control, with maternal reports on all variables. The model fit was fair, χ2(10, N = 168) = 22.634, p = .0088; CFI = .984, RMSEA = .087 (see Figure 2). As depicted by the central downward paths in the model, adolescent depressive symptoms in sixth grade predicted higher levels of mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade. However, higher conflict in seventh grade did not predict increased psychological control in eighth grade, although a trend was apparent. The CI for the indirect effect of depressive symptoms on psychological control via mother–adolescent conflict at p = .05 was [−.00055, .03032]. Because the CI included zero, mediation was not supported in this model. Furthermore, maternal psychological control in sixth grade predicted mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade; however, mother–adolescent conflict in seventh grade did not predict adolescent depressive symptoms in eighth grade (see central upward paths in the model). Given this nonsignificant path, there was no evidence that mother–adolescent conflict mediated the relation between prior maternal psychological control and subsequent adolescent depressive symptoms.

Exploratory Multigroup Gender Analyses

As noted above, descriptive analyses indicated that adolescent gender was uncorrelated with the model variables. However, it was possible that gender functioned as a moderator of the indirect pathways represented in the models. To test for moderated mediation, we used model constraint methods and examined the unstandardized difference between the indirect effect of the male model and the indirect effect of the female model, which was calculated as âmale* b̂male – âfemale* b̂female (Mplus; Muthén & Muthén, 2007). If this difference was significant at p < .05, then the mediated effect would be different for male and female groups, and this would constitute evidence for gender-moderated mediation (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). We also used model constraint methods to examine whether gender was a moderator of the separate a and b paths (âmale – âfemale for path a, and b̂male – b̂female for path b) for both adolescent and mother directions of indirect effects in each of the four models.

Moderated mediation results indicated that adolescent gender did not moderate any of the mediation pathways (i.e., the ab paths) between adolescent problem behaviors and maternal psychological control in any of the four hypothesized models (all ps > .05). Furthermore, examination of all separate a and b paths within our models indicated that gender appeared to moderate only one: Using mother reports, the path from adolescent depressive symptoms to mother–adolescent conflict was stronger for boys than for girls (âmale – âfemale = .728, SE = .215). In sum, analyses exploring the role of adolescent gender as a moderator of variable relations revealed virtually no patterns of moderation, whether moderated mediation or specific path tests for moderation were considered.

Discussion

Our findings indicated that the relations between prior adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms and subsequent maternal psychological control were indirect and mediated by mother–adolescent conflict, whether adolescent or mother reports were considered. We found no evidence of a reciprocal pattern of indirect effects; that is, there was no evidence that conflict mediated the relation between prior maternal psychological control and subsequent adolescent problem behaviors. These findings are consistent with developmental perspectives noting increased child effects on parenting during early adolescence (e.g., Kidwell et al., 1983; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). However, there was some evidence for reciprocal direct effects between both problem behaviors and conflict and between conflict and psychological control. Exploratory analyses indicated that adolescent gender did not moderate the mediating pathways in the models. Below, we discuss the specific direct links in our mediation pathways and the implications of our findings for research focused on parent and child effects during adolescence.

Adolescent Aggression, Depressive Symptoms, and Mother–Adolescent Conflict

Our findings revealed that higher levels of adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms predicted higher levels of subsequent mother–adolescent conflict, whether adolescent or mother reports were considered. There are several explanations for these relatively adolescent-driven connections between aggression, depressive symptoms, and conflict. Adolescent attributes such as aggressive behaviors may engender destructive parent–child relationships (Patterson, 1982). Aggressive behaviors are difficult for parents to manage, and this difficulty can lead to emotional dysregulation and interpersonal coercion, dyadic features that are likely to promote destructive conflict (e.g., Patterson, 1982; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Parents may also respond to their adolescent’s aggressive behaviors by raising their tolerance for problem behaviors (Bell & Chapman, 1986), enabling greater expressed aggression by the adolescent and fueling more conflict long term.

As with aggression, depressive symptoms may also foster parent–adolescent conflict. Parents’ initial sympathetic responses to their children’s depressive symptoms may erode over time (Coyne, 1976; Sheeber, Hops, & Davis, 2001), and frustrated parental reactions and negative affect likely create a context for increased conflict. In addition, expression of irritability and anger, which can be characteristic of adolescents with depressive symptoms, may elicit parental reciprocity of negative affect and thus increase parent–adolescent aversive exchanges (Sheeber, Allen, Davis, & Sorensen, 2000). Consequently, through mutual deficits in the ability to regulate negative emotions, parent–adolescent conflict is likely to ensue (Lindahl & Markman, 1990).

It is interesting that both aggression and depressive symptoms were similarly related to conflict. Aggression and depression are often comorbid during childhood and early adolescence (Garber, Quiggle, Panak, & Dodge, 1991) and may share similar symptoms and behaviors (e.g., anger, withdrawal, irritability). Such comorbidity may partially be explained by common risk factors including cognitive biases and deficits in emotion regulation (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). In particular, an “ill-tempered” interactional style and negative emotionality among adolescents are risk factors for externalizing and internalizing behaviors (Caspi, Elder, & Herbener, 1990) that may subsequently contribute to increased parent–adolescent conflict.

Mother–Adolescent Conflict and Maternal Psychological Control

We also found that higher levels of prior mother–adolescent conflict predicted higher levels of subsequent maternal psychological control. In interpreting these relations, we posit that parent–adolescent conflict may elicit negative forms of control from mothers who may be unsuccessful in regulating their own negative emotions and who may not be able to access or enact appropriate parenting strategies (see Grolnick, 2003; Sheeber et al., 2000, 2001).

More specifically, parents may use psychologically controlling behaviors during attempts to de-escalate conflict and ultimately control their adolescents. Conflicts engendered by adolescent problem behaviors are likely to be characterized by difficult interactions and coercive exchanges. During such conflicts, parents may blame, criticize, and induce guilt and anxiety without reflecting on their own behaviors. Mothers experiencing emotional distress have been found to use psychological control as a strategy for controlling their adolescents’ behaviors (Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997), indicating that psychological control is more likely when mothers feel overwhelmed (see also Soenens et al., 2008). Mothers engaged in conflict with their adolescents may also be more likely to use psychological control as an efficient, albeit inappropriate, means to manage their adolescents, rather than using affectively neutral control that may require more energy and emotion regulation (Barber & Harmon, 2002).

Adolescent–Versus Parent-Driven Indirect Model Relations

Overall, our results regarding adolescent-driven indirect effects are consistent with developmental and socialization theories proposing that children and adolescents elicit responses from their parents, and therefore contribute to the parenting they receive (Belsky, 1984; Kuczynski & Parkin, 2007; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Our findings are also in accord with conceptual models describing increasing adolescent influence on dyadic and parental behavior (e.g., Kidwell et al., 1983; Silverberg et al., 1992; see also Lytton, 1990; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Furthermore, our mediation findings are consistent with prior research indicating adolescent but not parent directions of effects in examinations of reciprocal relations between dimensions of parenting and adolescent problem behaviors (Albrecht et al., 2007; Loukas, 2009; Stice & Barrera, 1995). It is important to note, however, that although we did not find indirect pathways initiated by parenting in our models, there were significant correlations between prior psychological control and later adolescent problems. Additionally, there were significant model relations between prior psychological control and subsequent mother–adolescent conflict, particularly from sixth to seventh grade. The parent-driven effect was not sustained in these instances because the next pathways in the models, those between conflict and adolescent problems, were not significant. Perhaps in the context of a different mediator, an indirect parent-driven pathway may have been fully supported.

Furthermore, it is possible that the complexity of our models made it difficult to detect parent-driven patterns of indirect relations. Previous studies finding support for both adolescent and parent effects have not explored mediation, focusing instead on only direct reciprocal relations over time (Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005; Pettit et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2003; Soenens et al., 2008). There was also considerable rank-order stability in our measures of adolescent aggression and depressive symptoms over time, particularly from seventh to eighth grade; furthermore, this stability appeared somewhat greater than the stability exhibited by psychological control. The greater stability of adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems over time may have prevented the detection of significant relations between prior parenting and change in these problems (for similar findings, see Albrecht et al., 2007; Loukas, 2009). In addition, our study, while longitudinal and multiwave, considered only the early adolescent years. It is possible that a more complete picture of reciprocal adolescent and parent effects could emerge from a transactional, lifespan-oriented approach that assesses families from early childhood through later adolescence (e.g., Pettit et al., 2001).

Methodological and statistical caveats notwithstanding, the main implication of the present study is that socialization researchers should take seriously the exhortations about child effects on parenting articulated decades ago (e.g., Bell, 1968; Bell & Chapman, 1986; Belsky, 1984; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Our findings suggest that examination of the effects of psychological control on adolescent problem behaviors without simultaneous consideration of adolescent effects on parenting is severely limited (see also Albrecht et al., 2007; Loukas, 2009). Future efforts in this area should therefore be based on longitudinal data and should consider potential reciprocal relations between parenting and adolescent problem behaviors.

Our findings regarding adolescent gender also present implications for future research. We found no compelling gender differences in patterns of relations among psychological control, mother–adolescent conflict, and adolescent problem behaviors, whether adolescent or maternal reports were considered. Although some studies have revealed mixed or rather subtle patterns of adolescent gender effects (e.g., Conger et al., 1997; Pettit et al., 2001; Rogers et al., 2003; Soenens et al., 2008), others have found no evidence that adolescent gender moderates relations between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors (e.g., Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 2005; Loukas, 2009). Future explorations of gender-related effects in the absence of strong theoretical justification are unlikely to yield useful information. Furthermore, if examinations of gender effects are considered essential, researchers should utilize sophisticated approaches such as the multigroup analyses we employed.

Limitations and Contributions

Although there are several strengths of this study, some limitations remain. Although our data were longitudinal, questions of causality remain, as unmeasured variables could account for the pattern of observed relations. This common “third variable” problem is difficult to address, but it might be countered in study designs with direct experimental manipulation or in those evaluating parenting interventions. In addition, we used questionnaire data only, and interactional data might provide additional information on the dynamics assessed.

The current study also did not include father self-reports or adolescents’ reports about fathers. Some studies focused on connections between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors have found differences when mother– versus father–adolescent relations were considered (e.g., Conger et al., 1997; Pettit et al., 2001), whereas others have revealed highly similar patterns for both mother and father data (e.g., Barber et al., 2005; Soenens et al., 2008). Given these mixed findings, future research might productively explore patterns of mother and father differences (Stolz, Barber, & Olsen, 2005). In any case, collection of father data in the present study would have increased the generalizability of our findings beyond the mother–adolescent dyad.

In addition, as in many previous studies in this area (e.g., Barber, 1996; Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994; Conger et al., 1997), our sample was relatively homogenous, consisting mainly of European American dyads. We note that findings concerning potential moderating effects of race or ethnicity on relations between psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors have been mixed, with some studies finding no support for moderation (Barber et al., 2005; Steinberg, 2001; see also Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2010), and others finding at least some support for moderation (e.g., Chao & Aque, 2009). Assessment of diverse samples in future research may help clarify mixed findings, especially when such efforts are motivated by theory about potential cultural differences (e.g., Rudy & Halgunseth, 2005). In the present study, generalization of findings to diverse racial and ethnic groups is limited.

Despite these limitations, the current study makes several important contributions to the literature. We examined the temporal sequencing of indirect effects for simultaneous adolescent-driven and parent-driven longitudinal mediation models during the transition to adolescence. Furthermore, we tested these relations with a theoretically relevant mediating variable, conflict, and we included all variables measured at all time points. In addition, although previous research highlights the importance of using adolescents’ perceptions of psychological control (e.g., Barber & Harmon, 2002), others discuss the possibility of adolescent cognitive biases. For example, Rogers et al. (2003) mentioned that adolescents with higher levels of internalizing or externalizing problems may view their parents more negatively than adolescents without such problems. Our utilization of adolescent and maternal reports in separate models helps counter this potential problem.

Our results pertaining to the adolescent direction of indirect effects converge with recent findings that adolescent problem behaviors predict maternal psychological control, while psychological control does not predict problem behaviors (Albrecht et al., 2007; Loukas, 2009). It is important to replicate these patterns and to examine the possibility of reciprocal parent- and child-driven patterns of relations over different developmental epochs (e.g., childhood, late adolescence). Given our findings, future process-oriented research should also continue to examine mediators that may account for complex relations among parent and adolescent behaviors. Individual and dyadic variables may mediate reciprocal relations, and these potential patterns should be assessed. Such efforts will build a more complete understanding of how and why psychological control and adolescent development are related over time.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants awarded to Dawn M. Gondoli from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R03HD041955, 5R03HD41955-2), the University of Notre Dame Graduate School, and the University of Notre Dame College of Arts and Letters. We thank Scott E. Maxwell for statistical consultation, and we gratefully acknowledge the contributions of our study participants.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; Burlington: 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht AK, Galambos NL, Jansson SM. Adolescents’ internalizing and aggressive behaviors and perceptions of parents’ psychological control: A panel study examining direction of effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:673–684. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9191-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. doi:10.2307/1131780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, editor. Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. doi:10.1037/10422-000. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Harmon EL. Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 15–52. doi:10.1037/10422-002. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JE, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2005;70(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. Serial No. 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. doi:10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ, Chapman M. Child effects in studies using experimental or brief longitudinal approaches to socialization. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:595–603. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.5.595. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. doi:10.2307/1129836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder JMH, Herbener ES. Childhood personalityand the prediction of life-course patterns. In: Robins L, Rutter M, editors. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Aque C. Interpretations of parental control by Asian immigrant and European American youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:342–354. doi: 10.1037/a0015828. doi:10.1037/a0015828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Gondoli DM, Peeke L. Structure and validity of parent and teacher perceptions of children’s competence: A multitrait–multimethod–multigroup investigation. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:241–249. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.10.3.241. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Conger RD, Scaramella LV. Parents, siblings, psychological control and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:113–138. doi:10.1177/0743554897121007. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Nousiainen S. Maternal and paternal parenting: Critical dimensions in adolescent functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;7:213–221. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.213. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Quiggle NL, Panak W, Dodge KA. Aggression and depression in children: Comorbidity, specificity, and social cognitive processing. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction: Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 2. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 225–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:951–975. doi:10.1177/0192513X05286020. [Google Scholar]

- Gondoli DM, Silverberg SB. Maternal emotional distress and diminished responsiveness: The mediating role of parenting efficacy and parental perspective taking. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:861–868. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.861. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:707–716. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.707. [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS. The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy AM, Gondoli DM, Blodgett-Salafia EH. Hier-archical linear modeling analysis of change in maternal knowledge over the transition to adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:707–732. doi:10.1177/0272431609341047. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell JS, Fischer JL, Dunham RM, Baranowski MD. Parents and adolescents: Push and pull of change. In: McCubbin HI, Figley CR, editors. Stress and the family: Vol. 1. Coping with normative transitions. Brunner-Mazel; New York, NY: 1983. pp. 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Parkin CM. Agency and bidirectionality in socialization: Interactions, transactions, and relational dialects. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1268–1282. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM, Markman HJ. Communication and negative affect regulation in the family. In: Blechman EA, editor. Emotions and the family: For better or worse. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A. Examining temporal associations between perceived maternal psychological control and early adolescent internalizing problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:1113–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9335-z. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:683–697. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.5.683. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. doi: 10.3758/BF03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 5.2) [Computer software] Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family processes. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion T. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, Foster SL. Negotiating parent–adolescent conflict: A behavioral-family systems approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KN, Buchanan CM, Winchell ME. Psychological control during early adolescence: Links to adjustment in differing parent/adolescent dyads. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:349–383. doi: 10.1177/0272431603258344. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy D, Halgunseth LC. Psychological control, maternal emotion and cognition, and child outcomes in individualist and collectivist groups. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2005;5:237–264. doi:10.1300/J135v05n04_04. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype-environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parents’ behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. doi:10.2307/1126465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Allen N, Davis B, Sorensen E. Regulation of negative affect during mother-child problem-solving interactions: Adolescent depressive status and family processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:467–479. doi: 10.1023/a:1005135706799. doi:10.1023/A:1005135706799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Davis B. Family processes in adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1009524626436. doi:10.1023/A:1009524626436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Sorensen E. Family relationships of depressed adolescents: A multimethod assessment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:268–277. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_4. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg SB, Gondoli DM. Autonomy in adolescence: A contextual perspective. In: Adams GR, Montemayor R, Gullotta T, editors. Psychosocial development during adolescence. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. pp. 12–61. [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg SB, Tennenbaum DL, Jacob T. Adolescence and family interaction. In: Van Hasselt VB, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of social development: A lifespan perspective. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1992. pp. 347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana J, Gaines C. Adolescent-parent conflict in middleclass African American families. Child Development. 1999;70:1447–1463. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00105. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Luyckx K, Vansteenkiste M, Duriez B, Goossens L. Clarifying the link between parental psychological control and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Reciprocal versus unidirectional models. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54:411–444. doi:10.1353/mpq.0.0005. [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M. A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: Proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Developmental Review. 2010;30:74–99. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2009.11.001. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00001. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M. A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents’ substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.31.2.322. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz HE, Barber BK, Olsen JA. Toward disentangling fathering and mothering: An assessment of relative importance. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1076–1092. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00195.x. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Gondoli DM, Bonds DD, Salem LN. Mothers’ responsive parenting practices and psychological experience of parenting as mediators of the relation between marital conflict and mother-preadolescent relational negativity. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:327–355. doi:10.1207/s15327922par0304_3. [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater EA, Lansford JE. A family process model of problem behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:100–109. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00008.x. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Pomerantz EM, Chen HC. The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development. 2007;78:1592–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JC, Ollendick TH. The comorbidity of conduct problems and depression in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:201–220. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0011-3. doi:10.1007/s10567-006-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau J, Smetana JG. Adolescent-parent conflict among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Development. 1996;67:1262–1275. doi:10.2307/1131891. [Google Scholar]