Abstract

Purpose: This study aims to explore the clinical characteristics of ATP binding cassette E1 (ABCE1) in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) and its roles in the proliferation, invasiveness, migration and apoptosis of the human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells CAL-27. Methods: The expression of ABCE1 and its target protein-RNase L, were first studied in tumor tissues of OSCC and adjacent non-tumor tissues. Moreover, CAL-27cells were transfected by ABCE1-specific shRNA, then MTT assay, the transwell and scratch assay were used to study cell proliferation and migration activity; the apoptosis rate and cell cycle distribution were tested by flow cytometry. Western blot and RT-PCR assay were adopted to measure their silencing efficacy. Results: ABCE1 expression is low in the adjacent non-tumor tissues while the expression is high in the oral cancer; the expression is reversely proportional to the differentiation degrees. The expression of RNaseL was in contrary to ABCE1. After transfected with ABCE1-siRNA, the proliferation, invasiveness and migration capabilities of cells decreased significantly whilst the apoptosis rate enhanced greatly (P < 0.01). Meanwhile, the expression of ABCE1 in CAL-27 cells was blocked (P < 0.01) while the expression of RNase L increased significantly (P < 0.01). Conclusion: ABCE1 is closely connected with the pathogenesis and development of oral cancer, which acts through the cellular pathways of 2-5A/RNase L.

Keywords: ABCE1, RNase L, oral cancer, CAL-27 cells, siRNA

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, with approximately 540,000 new cases annually worldwide [1]. The molecular mechanisms related to the pathogenesis of this disease are still poorly understood. Early diagnosis is therefore fundamental for prognostic definition and therapy. In fact, in maxillofacial surgery, every demolitive operation influences the vital functions of respiration, phonation, chewing, and swallowing and implies complicated and expensive technologies for reconstruction. It is therefore crucial to understand the molecular mechanisms related to the pathogenesis of this disease in order to designate new and more effective diagnostic and prognostic strategies [2,3]. The main target is to identify new molecular markers that may be used in rapid and economic tests, which should be not invasive for OSCC patients.

ABCE1 is a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters superfamily and OABP subfamily, is expressed in the cytoplasm of various tissues and organs in mammals [4,5]. ABCE1 encodes a product of 68KD protein which is described as ribonuclease L (RNase L) inhibitor [6-8], and by forming a heterodimer with RNase L, ABCE1 protein inhibits the IFN-dependent 2-5A/RNase L system thus regulates a broad range of biological functions including viral infection, tumor cell proliferation, and anti-apoptosis [8-11]. Although several studies have reported the characters of ATP-binding cassette in the pathogenesis and development of lung cancer [12], colon cancer [13] and prostate cancer [14], ABCE1 was rarely reported in oral cancer. In the current study, we firstly studied the expression of ABCE1 and RNase L at oral cancer and the adjacent non-tumor tissues resected from oral cancer patients. Then we adopt the small interfering RNA (siRNA) to construct the siRNA vector of ABCE1, and transfect it into the CAL-27 cell lines of oral cancer to block the expression of gene ABCE1, thus investigate its role in the pathogenesis, development and treatment of oral cancer.

Materials and methods

The study was approved and registered by our Hospital Ethics Committee in August 2009, the related screening and analysis of resection sample were approved by the Ethics committee, and written consent for using these samples were signed and agreed by all subjects.

Resection sample collection

The oral cancer tissue and adjacent non-tumor tissue samples (at least 2 cm away from the edge of cancerous tissue) were collected from the sample preservation center of our hospital. These oral cancer (and adjacent non-tumor tissue) samples were all resected in the department of dentistry January 2010 to December 2012.

The inclusion criteria of these sample were: (i) patient did not receive any radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment before; (ii) each patient had received a medical examination which includes, but not limited to, CT scan, MRI and ECT, which could define the TNM stage of the patient clearly; (iii) Patients had received radical surgery with sufficient tissue samples prepared in paraffin blocks for further testing; Patients who had at least two concurrent primary tumors were excluded.

All samples were fixed in 10% formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. The samples were routinely serial sectioned with thickness of 5 µm, and then immunohistochemically stained. The oral cancers were confirmed by two senior pathologists and were classified according to the standard of the WHO histological classification, all cases were phased according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system stipulated by the seventh version of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in a stepwise xylene and graded ethanol, washed with PBS, and recovered through microwave irradiation. A 3% H2O2 solution were added and cultured for 10 minutes, and then washed with PBS. Goat blocking serum was supplied and cultured under room temperature and the diluted primary antibodies were applied (1:100). Sections, after staying overnight in 4°C, were applied PBS washing, then added with secondary antibodies and cultured in 37°C for 20 minutes. The newly-prepared DAB chromogenic reagent was applied, and cultured at 37°C for 5 to 10 minutes. Nuclei were then stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE).

Expressions of ABCE1 and RNaseL protein in tissue sample

Western blot was used to determine the protein level in the cancer tissues. Briefly, frozen tissues were homogenated with lysis buffer, then centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min (12000 r/min). The supernatant was collected; BCA method was used to determine protein concentration. A 10% polyacrylamide gel was prepared to load protein samples, 5% nonfat dry milk was added to block the non-specific antigen. The primary antibodies (Rabbit anti-human ABCE1 polyclonal antibody, and Mouse anti-human RNase L polyclonal antibody, Santa Cruz) and secondary antibodies were applied.

Cell lines

CAL-27 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). It was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C.

Preparation of target vector and transfection

About the strategy of RNA interference, we followed the same procedure described by Huang et al. [15]. Briefly, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting ABCE1 were chemically synthesized by Takara Biotechnology (Dalian) Co., Ltd. The two siRNA sequences were:

(Si-1) F: 5’GATCCGCTACAGCGAGTACGTTTACCTGTGAAGCCACAGATGGGGTAAACGTACTCGCTGTAGCTTTTTTG3’; (Si-1) R: 5’AATTCAAAAAAGCTACAGCGAGTACGTTTACCCCATCTGTGGCTTCACAGGTAAACGTACTCGCTGTAGCG3’; (Si-2) F: 5’GATCCGAGTACGATGATCCTCCTGACTGTGAAGCCACAGATGGGTCAGGAGGATCATCGTACTCTTTTTTG3’; (Si-2) R: 5’AATTCAAAAAAGAGTACGATGATCCTCCTGACCCATCTGTGGCTTCACAGTCAGGAGGATCATCGTACTCG3’; the negative scramble siRNA sequence was (Si-N) F: 5’GATCCGCGAGACCTCAGTATGTTACCTGTGAAGCCACAGATGGGGTAACATACTGAGGTC TCGCTTTTTTG3’ (control group).

The DNA sequence were fully ligated into RNAi-Ready pSIREN-DNR-DsRed-Expression Vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA ) at 4°C overnight by an TaKaRa DNA Ligation Kit. There were two targeted recombinant plasmids (ABCE1-SiRNA-1, ABCE1-SiRNA-2), and 1 negative control (ABCE1-SiRNA-N), untreated cells served as the blank control. Lipofectamine 2000 was used in transfection with the concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well (six-well plate) and 5 μg of recombinant plasmids.

MTT assay

The cells from four groups were loaded in 96-well plate with 4 × 103 cells per well, cultured with the DMEM medium with 10% FBS, at time points of 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours. The medium was removed from each well and 100 μl of 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT; 0.5 mg/ml in PBS) was added in the absence of light; formazan crystals were produced over a 4 h incubation period. To dissolve crystals, 150 μl of 0.04 N HCl in isopropanol was added to each well and the optical density at 540 nm was measured on a Tecan Spectrophotometer (Tecan SPECTRAFluor, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Transwell assay

Forty eight hours after the transfection, the full medium was changed into serum-free culture medium. Eight hours later, they were digested to a suspension with a density of 1 × 104/ml. Cells were seeded into the transwell chamber (Millipore, USA) which membrane was coated by a dilution of Matrigel (50 mg/L). The chamber was placed into a 24 well culture plate, with 500 µl of 1640 medium containing 15% serum added outside of the chamber, and 200 µl cell suspension were added in the chamber. 72 hours later, the cells were stained by crystal blue buffer and placed under the microscope for observation and counting.

Scratch assay

The migration capacity of CAL-27 cells was performed in a 24-well culture plate. After transfection, a horizontal wound (scratch) was made on the cells with a tiny spear. Cell migration was observed at 24, 48 and 72 hours after the transfection, the scratch spaces were analyzed.

Flow cytometry

Forty eight hours after the transfection, the cells were washed with PBS twice, and then digested and centrifuged. Then apoptosis detection was processed according to the instructions of the Detection Kit (PE, Annexin V Apoptosis I): Cells were resuspended with 1 × binding buffer (1 × 106/ml). A total of 100 µl was drawn, 5 µl of PE Annexin V and 5 µl of 7-AAD were added. Cells were cultured in a rotary system under room temperature for 15 minutes, added with 400 µl of 1 × binding buffer, and placed for analysis within one hour.

Knock-down efficiency

Forty eight hours later, western blot and Real time-PCR were used to analyze the knock-down efficiency. The primers of RT-PCR were designed and synthesized by Takara company (Dalian, China), with the sequence of ABCE1-Forward: 5’CCAGGTGAAGTTTTGGGATTAG3’ and ABCE1-Reverse: 5’AGGTTTGATGATGGCTTTTAGG3’. After total cellular RNA was extracted, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a super reverse transcription kit (Life technologies, USA). ABCE1 was amplified using the ABI 7500 Real-time PCR System, GAPDH served as internal control. The amplification performed as follows: one cycle of pre-denaturation at 95°C 5 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturing at 95°C for 15 s and extension at 60°C for 1 min. SYBR® Green Real-Time PCR Master Mixes (Life Technologies, USA) were used.

Western blot was used to determine the protein level of ABCE1 in the four groups and the procedure was same as mentioned above.

Statistical analysis

The images are analyzed by Quantity One software. All laboratory data are represented as “Mean ± Standard Deviation (S.D.)”. The chi-square test and single factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed with the SPSS17.0 software, a significant difference was considered for P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 245 samples were selected successfully, 153 of them were resected from males and 92 from females, with the average age of 61 years (ranging from 38 to 82). Of them, 44 cases were highly differentiated, 110 cases were moderately differentiated, and 94 cases were differentiated lowly. 111 cases were under stage III (stage I and stage II), and 134 cases were stage III and stage IV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relationship between positive expression of ABCE1 protein in oral squamous cell carcinomas and patient characteristics

| ABCE1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N (245) | - | + | ++ | X2 | P | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 193 | 22 | 57 | 74 | 1.634 | 0.442 |

| Female | 92 | 10 | 30 | 52 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | 147 | 24 | 44 | 79 | 1.193 | 0.551 |

| > 60 | 98 | 20 | 24 | 54 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | ||||||

| High | 44 | 17 | 23 | 4 | ||

| Moderate | 110 | 12 | 32 | 66 | 64.373 | 0.000 |

| Low | 91 | 5 | 14 | 72 | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I + II | 111 | 68 | 33 | 10 | 102.971 | 0.000 |

| III + IV | 134 | 12 | 31 | 91 | ||

ABCE1 is highly expressed in low differentiated oral cancer tissue

Immunohistochemistry showed the ABCE1 protein was mainly expressed in cytoplasm as yellow or brown-color staining. Its expression was significantly higher in low differentiated cells compared with highly differentiated cells. A few of expressions existed in the cytoplasm of normal oral cells, yet the expressions decreased in the enveloping layer cells. There are 86.9% (213 cases of 245) positive expressions of ABCE1 protein in oral cancer tissues while the rate of positive expression was significantly low in adjacent non-tumor tissues (8.98%, 22 of 245, P < 0.05). The expression of ABCE1 in the oral cancer tissues had no correlation with the age and gender of the patients (showed in Table 1), yet there was a statistical differences between the differentiation of oral cancer cells (X2 = 64.373, P = 0.000), and the degree of differentiation is negatively correlated with the expression of ABCE1. There is also a statistical differences in the expression of ABCE1 with the TNM stages in oral cancer (X2 = 102.97, P = 0.000), and the expression is positively correlated with the TNM stages.

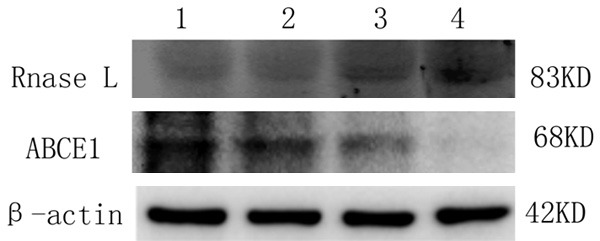

Expression of ABCE1 is low in the adjacent non-tumor tissues while high in oral cancer tissues

Western blot results (Figure 1) showed ABCE1 expressed lowly in adjacent non-tumor tissues of oral cancer, and expressed highly in oral cancer tissues. And the lower the degree of differentiation is, the higher the expression. On the contrary, RNaseL expressed highly in adjacent non-tumor tissues of oral cancer, and the higher the degree of differentiation was, the lower the expression was.

Figure 1.

Expression of ABCE1 protein and RNaseL protein in the oral cancer and its adjacent non-tumor tissues. Sample 1 is poorly-differentiated carcinoma, sample 2 is moderately-differentiated, and sample 3 is well-differentiated, and 4 is the adjacent non-tumor tissues.

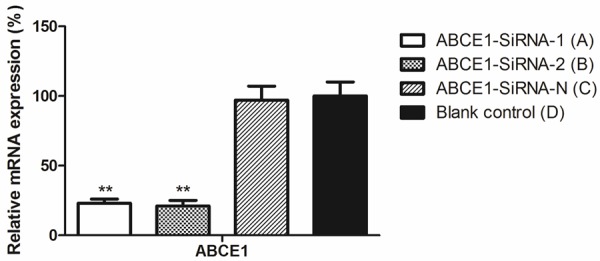

Decreased expression of ABCE1 in transfected CAL-27 cells

Aimed to examine the knocking-down efficiency, we isolated mRNA and protein in the CAL-27 cells from four groups to run real-time PCR and Western blot, to test the expression level of ABCE1. Compared with ABCE1-SiRNA-N group and the empty control group, real time PCR result showed that after the transfection, the RNA expression of ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 significantly decreased (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Transfection of siRNA down-regulated the expression of ABCE1 by real-time PCR. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control.

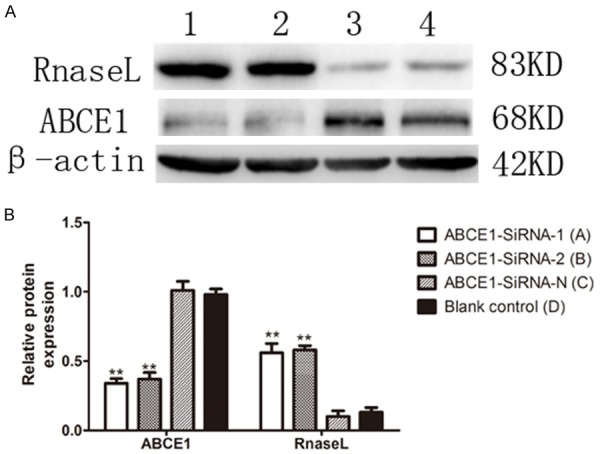

Western blot result (Figure 3A) showed that the expression of ABCE1 protein was inhibited significantly in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 group compared with blank control and ABCE1-SiRNA-N group (P < 0.05, Figure 3B), while the expression of ABCE1SiRNA-N group almost remained unchanged compared to blank control; on the contrary, the expression of RNase L increased significantly in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 group compared with blank control (P < 0.05), and the expression in ABCE1-SiRNA-N group was almost same with blank control (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Expression of ABCE1 decreased while RNase L increased after transfection, β-actin served as control. A. Western blotting representation; B. The expression displayed by column chart. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control. Figure shows the width of the scratch in each time period of each group of cells. *P < 0.01, compared with group D and ABCE1-SiRNA-N group.

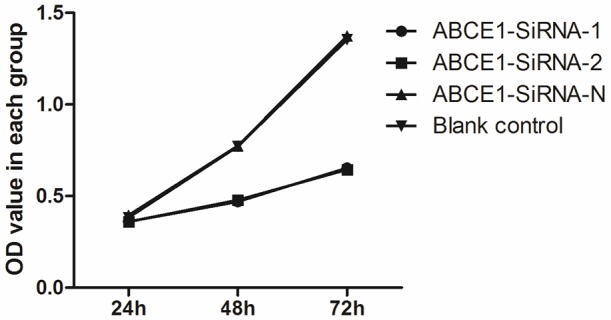

Decreasing of proliferation and migration ability after transfection

MTT test showed the proliferation of cells in ABCE1-SiRNA-N and blank control group increased almost 3 folds within 72 hours after transfection (Figure 4), while the proliferation in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 were relatively slow, which increased only 1 fold within 72 hours. Compared with negative control, the proliferation was retarded significantly (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Proliferation tested by MTT assay. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control.

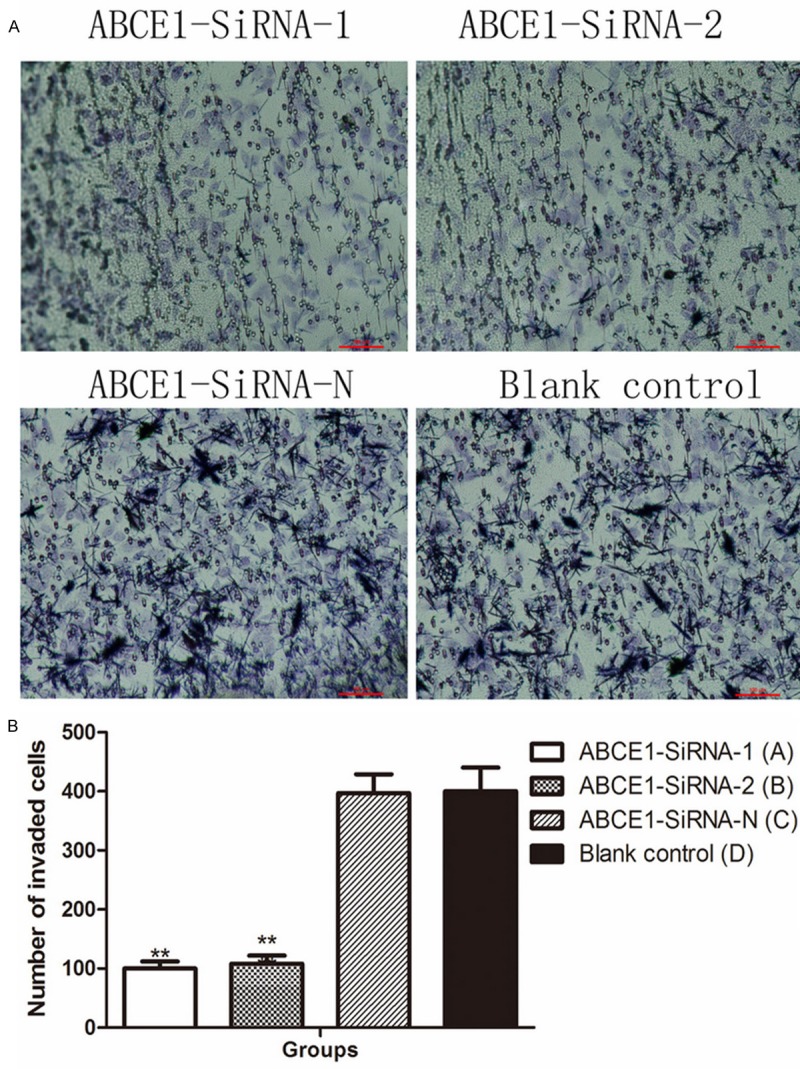

The migration ability test of transfected cell was performed 72 hours after the transfection. The transmembrane cell numbers in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 were only approximately 25% of the numbers in ABCE1-SiRNA-N and blank control group (Figure 5); this indicated that the migration ability was inhibited significantly in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 groups.

Figure 5.

Migration ability was decreased after transfection. (A) Representative pictures of transwell migration assay (B) column diagram of transmembrane cell count. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control.

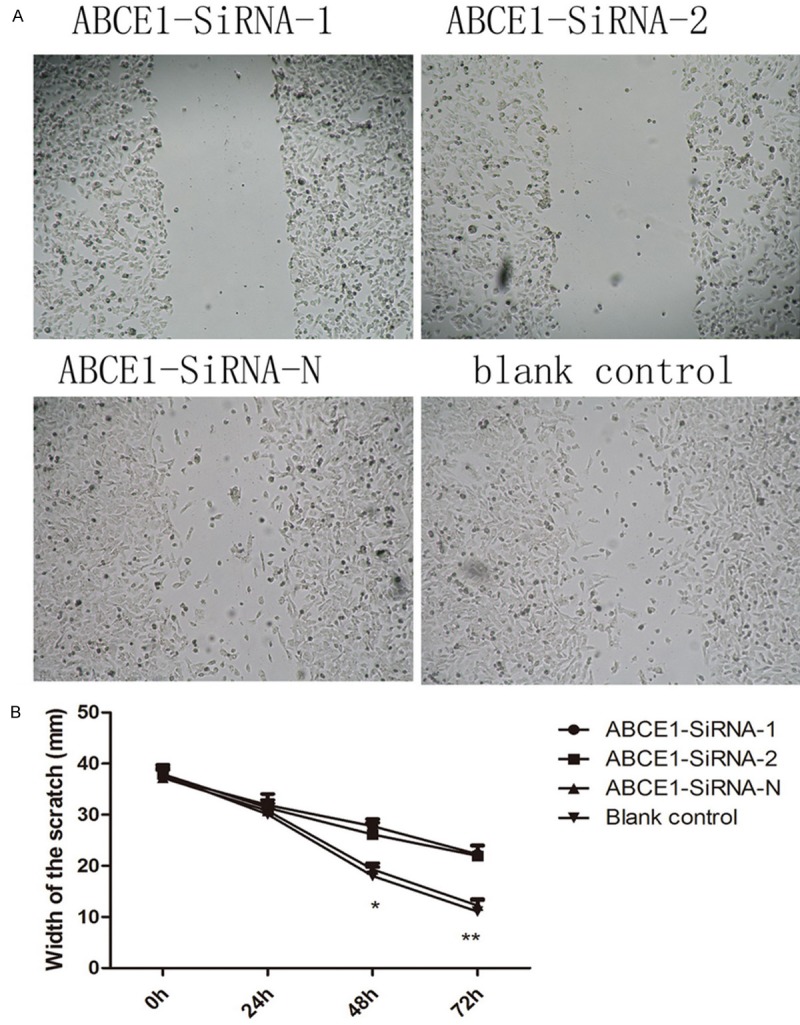

The scratch width measure results supported the results of the transwell assay: the reducing space in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 from 0 to 72 hours after the transfection was far below those measured from ABCE1-SiRNA-N and blank control group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Scratch assay suggests depleting ABCE1 reduces the migration ability of CAL-27. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control.

Apoptosis rate increased and G1/M blocking after transfection

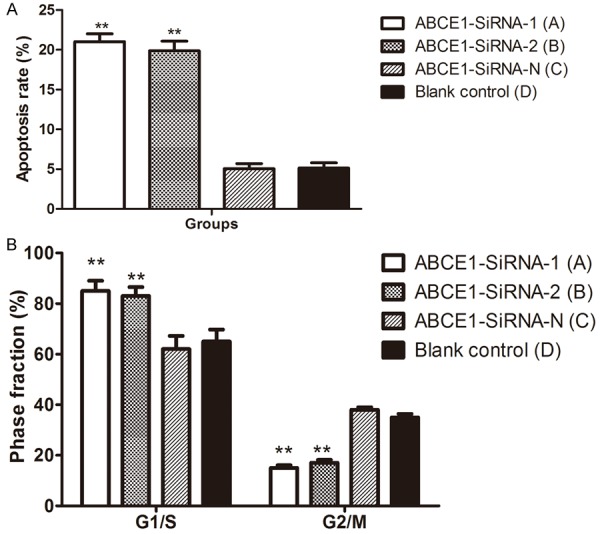

Flow cytometry analysis showed the apoptosis rate increased significantly (P < 0.01) in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 transfected cells, compared to negative control; While there is no significant change in the apoptotic rate between cells transfected with ABCE1-SiRNA-N (P > 0.05) and blank control (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Analysis of the rate of apoptosis (A) and cell cycle distribution (B) of each group of cells. **P < 0.01, compared with blank control.

G1/S arrest was also noticed in ABCE1-SiRNA-1 and ABCE1-SiRNA-2 transfected cells (P < 0.01), compared to negative control; while there is no significant change in the distribution of cell cycle between cells transfected with ABCE1-SiRNA-N (P > 0.05) and blank control (Figure 7B).

Discussion

Recent research have indicated that gene ABCE1 has an over-expression in lung adenocarcinoma [16], esophageal carcinoma [15] and prostatic carcinoma [11]. After the targeted silencing of gene ABCE1, there is a distinct change in the proliferation and apoptosis of tumor cells [16-18]. Some findings suggest that the mutation of gene ABCE1 could lead to the changing of pathogenesis, development and metastasis of genetic prostatic carcinoma [19,20].

So far, there is rare report about the role of gene ABCE1 in the oral cancer. In this report, we observed that ABCE1 was highly expressed in the OSCC tissues from patients, compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues. Importantly, we observed that the expression of ABCE1 is closely related to cancer cell differentiation and TNM stages, which suggested that ABCE1 might contribute to invasion and metastasis of OSCC. Based on that, we depleted it in CAL-27 cells, which showed high level of ABCE1 expression and strong invasive ability, and confirmed that ABCE1 plays a major role in controlling the cell invasion, migration, and motility. All of our results are in consistence with clinical findings, suggesting targeting ABCE1 could be a strategy for the development of OSCC therapy.

ABCE1 belongs to the gene subfamily of ATP-binding cassette transporters which express in the cytoplasm and the karyotheca. Compiling experimental evidences have showed that ABCE1 protein is the inhibitor the ribonuclease L (RNase L) [6-8]. Studies have showed that RNase L could specifically bind with and degrade RNA within cells, thus prevent the biosynthesis of protein at the translation level, and leading to the apoptosis of cells [8-10]. ABCE1 play an important role by forming a heterodimer with RNase L in inhibiting this pathway during the apoptotic process of cells [10,11].

The 2’-5’ oligoadenylate (2-5A)/RNase L system is one of the principle enzymatic pathways induced by interferon (IFN). RNase L mediates cell apoptosis and plays a significant role by regulating RNA expression. Increased 2-5A level within the cells plays an up-regulating role to the RNaseL activity, whilst down-regulates the ABCE1 protein [21,22].

The discovery of 21-23 nucleotide RNA duplexes, called small interference RNA (siRNA) may well be one of the transforming events in biology in the past decade, which has become a powerful tool for studies on gene function, carcinoma and viral disease therapy [23,24]. Zheng et al. constructed an siRNA-expression vector for targeting ABCE1 gene in lung carcinoma cells 95-D and NCI-H446 with a satisfactory transfection efficiency of 42.7% [25]. Enlightened by his work, we studied the expression difference of ABCE1 and RNaseL in oral cancer tissues and their adjacent non-tumor tissues. In our study, knocking down ABCE1 can significantly induce apoptosis and G1/S arrest, while we did not find any difference between blank control and ABCE1-siRNA-N control. These results indicate that the safety and efficacy of interfering vector system is reliable in the cell level, and ABCE1 is an ideal target for oral cancer.

Previous investigation also finds out that the siRNA expression vector transfected with gene ABCE1 has an impact on the proliferation, invasiveness, migration and apoptosis of the tumor cells of human small-cell lung cancer [18]. This suggests that gene ABCE1 might serve as the candidate for the pathogenesis and metastasis of tumors. A wide array of genes which could affect the pathogenesis and development of lung cancer have been investigated, targeted RNAi of CXCR4, MMP-2, XIAP, MTA1and surviving have been reported for the lung cancer in vitro or in vivo with down-regulation ranged from 20%-80% [26-28]. Yet very rare reports study the role of gene ABCE1 to the oral cancer. Our study demonstrates that ABCE1 could be a future target in the treatment of oral cancer.

In summary, our study showed that ABCE1 has a high expression in the oral cancer tissues, and the lower the degree of differentiation is, the higher the expression. The transfection vector system we constructed could inhibit the expression of ABCE1 successfully; the in vivo toxicity and efficiency will be the focus in our future research.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by Independent Innovation Foundation of Shandong University (IIFSDU), No. 2012TS165 & No. 2012JC031; also supported by Medical and Health Technology Development Plan of Shandong Province (No. 2013WSB20018).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Aquino G, Sabatino R, Cantile M, Aversa C, Ionna F, Botti G, La Mantia E, Collina F, Malzone G, Pannone G, Losito NS, Franco R, Longo F. Expression analysis of SPARC/osteonectin in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: from saliva to surgical specimen. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:736438. doi: 10.1155/2013/736438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohavanichbutr P, Houck J, Doody DR, Wang P, Mendez E, Futran N, Upton MP, Holsinger FC, Schwartz SM, Chen C. Gene expression in uninvolved oral mucosa of OSCC patients facilitates identification of markers predictive of OSCC outcomes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C, Mendez E, Houck J, Fan W, Lohavanichbutr P, Doody D, Yueh B, Futran ND, Upton M, Farwell DG, Schwartz SM, Zhao LP. Gene expression profiling identifies genes predictive of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2152–2162. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karcher A, Buttner K, Martens B, Jansen RP, Hopfner KP. X-ray structure of RLI, an essential twin cassette ABC ATPase involved in ribosome biogenesis and HIV capsid assembly. Structure. 2005;13:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braz AS, Finnegan J, Waterhouse P, Margis R. A plant orthologue of RNase L inhibitor (RLI) is induced in plants showing RNA interference. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:20–30. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisarev AV, Skabkin MA, Pisareva VP, Skabkina OV, Rakotondrafara AM, Hentze MW, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The role of ABCE1 in eukaryotic posttermination ribosomal recycling. Mol Cell. 2010;37:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. Characterization of the human ABC superfamily: isolation and mapping of 21 new genes using the expressed sequence tags database. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diriong S, Salehzada T, Bisbal C, Martinand C, Taviaux S. Localization of the ribonuclease L inhibitor gene (RNS4I), a new member of the interferon-regulated 2-5A pathway, to 4q31 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1996;32:488–490. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Deen M, de Vries EG, Timens W, Scheper RJ, Timmer-Bosscha H, Postma DS. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in normal and pathological lung. Respir Res. 2005;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodnina MV. Protein synthesis meets ABC ATPases: new roles for Rli1/ABCE1. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:143–144. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian Y, Han X, Tian DL. The biological regulation of ABCE1. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:795–800. doi: 10.1002/iub.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren Y, Li Y, Tian D. Role of the ABCE1 gene in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:965–970. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shichijo S, Ishihara Y, Azuma K, Komatsu N, Higashimoto N, Ito M, Nakamura T, Ueno T, Harada M, Itoh K. ABCE1, a member of ATP-binding cassette transporter gene, encodes peptides capable of inducing HLA-A2-restricted and tumor-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes in colon cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea PR, Ishwad CS, Bunker CH, Patrick AL, Kuller LH, Ferrell RE. RNASEL and RNASEL-inhibitor variation and prostate cancer risk in Afro-Caribbeans. Prostate. 2008;68:354–359. doi: 10.1002/pros.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang B, Gong X, Zhou H, Xiong F, Wang S. Depleting ABCE1 expression induces apoptosis and inhibits the ability of proliferation and migration of human esophageal carcinoma cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:584–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren Y, Li Y, Tian D. Role of the ABCE1 gene in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:965–970. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu DZ, Tian DL, Ren Y. [Expression and clinical significance of ABCE1 in human lung adenocarcinoma] . Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2008;30:296–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang B, Gao Y, Tian D, Zheng M. A small interfering ABCE1-targeting RNA inhibits the proliferation and invasiveness of small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25:687–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiang Y, Wang Z, Murakami J, Plummer S, Klein EA, Carpten JD, Trent JM, Isaacs WB, Casey G, Silverman RH. Effects of RNase L mutations associated with prostate cancer on apoptosis induced by 2’,5’-oligoadenylates. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6795–6801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman RH. Implications for RNase L in prostate cancer biology. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1805–1812. doi: 10.1021/bi027147i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iordanov MS, Paranjape JM, Zhou A, Wong J, Williams BR, Meurs EF, Silverman RH, Magun BE. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase by double-stranded RNA and encephalomyocarditis virus: involvement of RNase L, protein kinase R, and alternative pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:617–627. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.617-627.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisbal C, Martinand C, Silhol M, Lebleu B, Salehzada T. Cloning and characterization of a RNAse L inhibitor. A new component of the interferon-regulated 2-5A pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13308–13317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia L, Guan W, Wang D, Zhang YS, Zeng LL, Li ZP, Wang G, Yang ZZ. Killing effect of Ad5/F35-APE1 siRNA recombinant adenovirus in combination with hematoporphrphyrin derivative-mediated photodynamic therapy on human nonsmall cell lung cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:957913. doi: 10.1155/2013/957913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi X, Zhao G, Zhang H, Guan D, Meng R, Zhang Y, Yang Q, Jia H, Dou K, Liu C, Que F, Yin JQ. MITF-siRNA formulation is a safe and effective therapy for human melasma. Mol Ther. 2011;19:362–371. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng MG, Gao Y, Huang B, Tian DL, Yang CL. Suppression of ABCE1 Leads to Decreased Cell Proliferation and Increased Apoptosis in 95-D and NCI-H446 Lung Carcinoma Cells. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2009;36:1475–1482. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang T, Mi Y, Pian L, Gao P, Xu H, Zheng Y, Xuan X. RNAi targeting CXCR4 inhibits proliferation and invasion of esophageal carcinoma cells. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Shen YG, Xu YJ, Shi ZL, Han HL, Sun DQ, Zhang X. Effects of RNAi-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene silencing on the invasiveness and adhesion of esophageal carcinoma cells, KYSE150. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:32–37. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1864-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Ding F, Luo A, Chen A, Yu Z, Ren S, Liu Z, Zhang L. XIAP is highly expressed in esophageal cancer and its downregulation by RNAi sensitizes esophageal carcinoma cell lines to chemotherapeutics. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:973–980. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]