Abstract

Glutamine metabolism is essential for tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer, cancer cells remodel their glutamine metabolic pathways to fuel rapid proliferation. SLC1A5 is an important transporter of glutamine various cancer cells. In this study, we investigated SLC1A5 protein expression in colorectal cancer and evaluated its clinical significance and functional importance. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on tissue microarrays containing 90 pairs of cancer and adjacent normal tissues from colorectal cancer patients, we found that SLC1A5 expression increased significantly in colorectal cancer compared with normal mucosa tissues (P < 0.001). We further validated SLC1A5 overexpression in 12 pairs of fresh cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues from colorectal cancer patients by Western blot (P < 0.05). SLC1A5 expression levels were strongly associated with T stage of tumor (P < 0.05), and the tubular adenocarcinoma subtype (P < 0.001). Moreover, downregulation of SLC1A5 by synthetic siRNA could suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis in colorectal cancer cell lines HT29 and HCT116. In conclusion, our results provide for the first time the differential expression in human colorectal cancer and normal tissues, and a functional link between SLC1A5 expression and growth and survival of colorectal cancer, making it an attractive target in colorectal cancer treatment.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, SLC1A5, tumorigenesis, therapeutic target

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third common cancer worldwide, 40-45% of colorectal cancer patients will develop metastases during the disease course, thus leading to a high mortality rate. The surgery based multidisciplinary treatmentincluding chemotherapy, radiotherapy and monoclonal antibodies improved the survival of colorectal cancer patients significantly, however the 5-year survival rate still remain at about 10% [1]. Knowledge on the molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer still remains poor, and more effective therapeutic targets are urgently needed to improve the poor survival of patients.

Energy metabolism reprogramming is considered an important hallmark of cancer cells, emerging discoveries indicate a variety of oncogenes and tumor suppressors participate in maintaining the metabolic hallmark of cancer [2]. Importantly, new therapeutics targeting metabolic pathways demonstrated high translational potential, such as L-asparaginase in treatment of leukemia. Glutamine is an abundant and versatile nutrient in plasma (0.6-0.9 mmol/L), the requirement of glutamine for rapid proliferating cancer outpaces normal supply, making glutamine a conditional essential nutrient [3]. Glutamine is considered at the center of cell growth and metabolism both in normal and cancer cells, glutaminolysis is used to replenish intermediates for TCA cycle and provide nitrogen resource for biosynthesis of nucleotides, proteins and reductive substances, moreover, glutamine participates in cell signaling pathway to promote hallmarks of malignancies including sustaining proliferation, invasion and metastasis [3]. Emerging evidences implied that glutamine metabolism is an appealing target for cancer treatment, c-Myc induced liver tumors displayed glutamine addiction phenotype in vivo [4], a small molecular inhibitor targeting glutaminase, which catalyzes hydrolysis of glutamine to glutamate, inhibits malignant transformation induced by Rho GTPase [5].

Our previous research showed that colorectal cancer also depends on glutamine to proliferate and survive, the key enzyme in glutamine catabolic pathway glutaminase is significantly upregulated in human colorectal cancer tissues,indicating glutamine metabolism pathway might be a promising therapeutic target [6]. SLC1A5 is a high-affinity transporter of glutamine in various cancer, emerging evidence indicate that SLC1A5 might provide survival advantage to cancer cells. Recent research demonstrated that SLC1A5 expression is upregulated in lung cancer and melanoma, and targeting glutamine transport mediated by SLC1A5 inhibits growth and survival of cancer cells [7,8], however the situation in colorectal cancer remains obscure.

In this paper, we compared expression level of SLC1A5 in human colorectal cancer with normal tissues, evaluated functional importance of glutamine transport mediated by SLC1A5 in cancer cell proliferation and survival, and identified SLC1A5 in glutamine metabolism pathway as another promising therapeutic target of colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and tissue microarray

Ninety patients diagnosed with pathologically proven colorectal cancer were selected during 2008-2010 from Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Hubei, China) as approved by the Human Ethics Review Board. All patients were informed and agreed with sample collection. Cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues were collected in surgery and tissue microarrays (TMA) were prepared in cooperation with National Engineering Center for Biochip at Shanghai, according to protocols previously described [9]. The TMA consisted of 79 tubular adenocarcinomas and 11 mucinous adenocarcinomas, demographic and clinical characteristics of the 90 patients are summarized in Table 1, and the 7th AJCC stage system was used.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients in the tissue microarray cohort according to the cancer status and SLC1A5 expression

| Total Number (90) | SLC1A5 (-) | SLC1A5 (+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Patients demographics | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 68.5 ± 11.1 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 47 (52) | 4 (9) | 41 (91) |

| Female | 43 (48) | 3 (7) | 38 (93) |

| Histology | |||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma | 79 (88) | 0 (0) | 79 (100) |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 11 (12) | 7 (64) | 4 (36) |

| T stage | |||

| 1 | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) |

| 2 | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) |

| 3 | 70 (78) | 5 (7) | 65 (93) |

| 4 | 11 (12) | 2 (18) | 9 (82) |

| N stage | |||

| 0 | 56 (62) | 0 (0) | 56 (100) |

| 1 | 25 (28) | 2 (8) | 23 (92) |

| 2 | 9 (10) | 1 (11) | 8 (89) |

| M stage | |||

| 0 | 88 (98) | 7 (8) | 81 (92) |

| 1 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Left semicolon | 48 (53) | 5 (10) | 43 (90) |

| Right semicolon | 32 (36) | 2 (6) | 30 (94) |

| Others | 10 (11) | 3 (30) | 7 (70) |

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohol. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclave sterilization in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 2 minutes. Endogenous peroxidaseactivity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 minutes. Sections were blocked by goat serum solution for 20 minutes at room temperature, and incubated with 1:500 rabbit anti-SLC1A5 antibody (BIOSS, bs-0473R) at 4°C overnight, then sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. SLC1A5 staining were visualized after DAB incubation and followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. PBS was used instead of the primary antibody as negative control. Staining results were assessed by two pathologists independently.

Staining intensity and proportion were both considered in the scoring system: 0 (no or weak staining, positive proportion < 10%), 1 (weak staining, positive proportion 10-40%), 2 (moderate staining, positive proportion 40-70%), 3 (strong staining, positive proportion > 70%).

Cell culture

Human colorectal cancer cell lines HT29 and HCT116 were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37°C, 100% humidity, and 5% CO2. Cells were passaged every 2-3 days and experiments were done when cells in exponential growth.

Tissue homogenization and Western blot

12 pairs of fresh cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues were collected in surgery from pathologically proven colorectal cancer patients. All the patients were selected and informed as described above. Fresh tissues were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 45 minutes, samples were then centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant was collected and subject to protein quantification by Bradford assay.

Western blot were done as described previously [10]. In brief, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% fat free milk dissolved in PBST, incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, and then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce), and β-actin was used as loading control. Intensity of bands were quantitative analyzed with Gel-Pro analyzer (Exon-Intron, Bob Farrell USA). Working concentrations of rabbit anti-SLC1A5 antibody (BIOSS, bs-0473R) 1:500.

MTT and apoptosis assays

After treatment, cells were seeded into 96-well plate and cultured for 24, 48, 72 hours, then incubated with MTT (5 mg/ml) at 37°C for 4 hours, and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured by microplate reader.

Apoptosis was evaluated by Annexin V/PI double staining kit (Merck) according to the instructions. After treatment, cells were harvested and incubated with Annexin V solution for 15 minutes at room temperature, and stained by PI solution. Then cells were subjected to analysis by C6 Accuri Flow Cytometer.

Statistical analysis

The association between SLC1A5 expression and demographic and clinical characteristics of patients was analyzed using Likelihood Ratio test. Data comparing two different conditions were analyzed by Student t test or Pearson’s χ2 test and results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experimental data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and statistical analyses were done with SPSS 18.0.

Results

SLC1A5 expression is upregulated in human colorectal cancer as evidenced by Immunohistochemistry

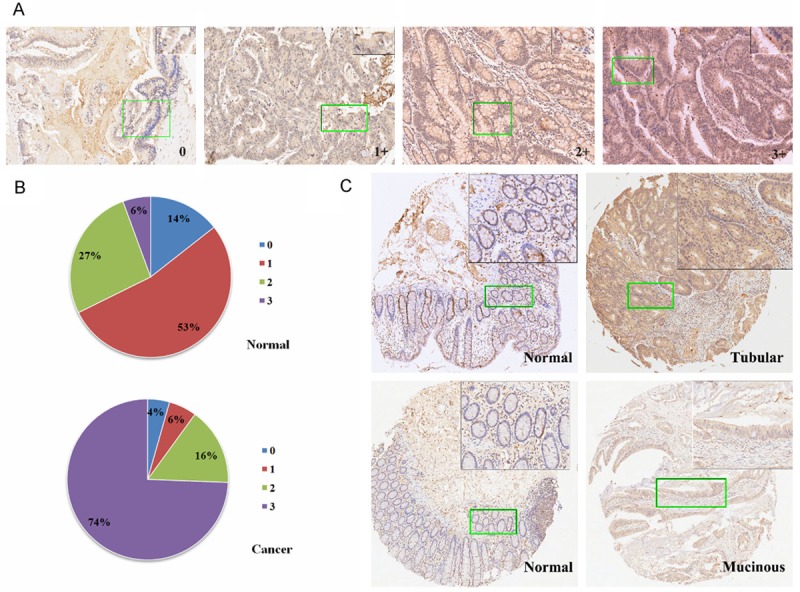

To evaluate the expression pattern of SLC1A5 in colorectal cancer, we conducted immunohistochemical analysis using tissue microarrays containing 90 pairs of primary colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues, which were collected from patients diagnosed with different histologic subtypes of colorectal cancer, representative staining and scoring criteria is shown in Figure 1A. Most cancer tissues exhibited obvious immunoreactivity for SLC1A5 with staining scores ranging from 2+ to 3+, whereas most normal intestinal epithelial cells exhibited weak staining with staining scores ranging from 0+ to 2+ (Figure 1B). Cellular location of SLC1A5 staining was mainly cytoplasmic with less along the cytoplasmic membrane, which is consistent with previous reports [11,12]. Then we analyzed the difference of SLC1A5 staining between normal and cancer tissues statistically, positivity was defined as IHC score > 0. As shown in Table 2, SLC1A5 staining were positive in 83 of 90 (92%) in colorectal cancer tissues and 65 of 90 (72%) in adjacent normal mucosa tissues (P < 0.001). Therefore, SLC1A5 expression is significantly upregulated in colorectal cancer compared with normal mucosa. Moreover, SLC1A5 staining were seen in 79 of 79 (100%) tubular adenocarcinoma and 4 of 11 mucinous adenocarcinoma subtypes (Figure 1C), suggesting different metabolic profiles in mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

SLC1A5 expression is upregulated in human colorectal cancer as evidenced by Immunohistochemistry. A. Representative images of IHC staining for SLC1A5 in a tissue microarray containing 90 pairs of primary colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues. 0, 1+, 2+ and 3+ staining images of colorectal cancer sections were shown, and a zoomed image of a selected area were shown in the top right corner. B. A representative pair of sections of normal colorectal mucosa and adenocarcinoma tissues (above panels), and a pair of normal colorectal mucosa and mucinous adenocarcinoma tissues (inferior panels), a zoomed image of a selected area were shown in the top right corner.

Table 2.

Comparison of SLC1A5 expression in colorectal cancer and normal tissues

| SLC1A5 IHC Scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Patients demographics | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | P value |

| Gender | 0.967 | ||||

| Male | 4 | 2 | 15 | 25 | |

| Female | 3 | 2 | 13 | 26 | |

| Histology | < 0.001 | ||||

| Tubular adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 | 28 | 51 | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| T stage | 0.021 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | |

| 3 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 45 | |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 5 | |

| N stage | 0.978 | ||||

| 0 | 4 | 2 | 18 | 32 | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 14 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |

| M stage | 0.009 | ||||

| 0 | 7 | 4 | 26 | 51 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Tumor location | |||||

| Left semicolon | 5 | 1 | 12 | 30 | 0.083 |

| Right semicolon | 2 | 3 | 13 | 14 | |

| Others | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

Statistics of IHC staining scores for SLC1A5 in a tissue microarray containing 90 pairs of primary colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues, statistical significance was assessed by Pearson’s χ2 test and the difference was significant with P < 0.001.

SLC1A5 expression is upregulated in human colorectal cancer as evidenced by Western blot

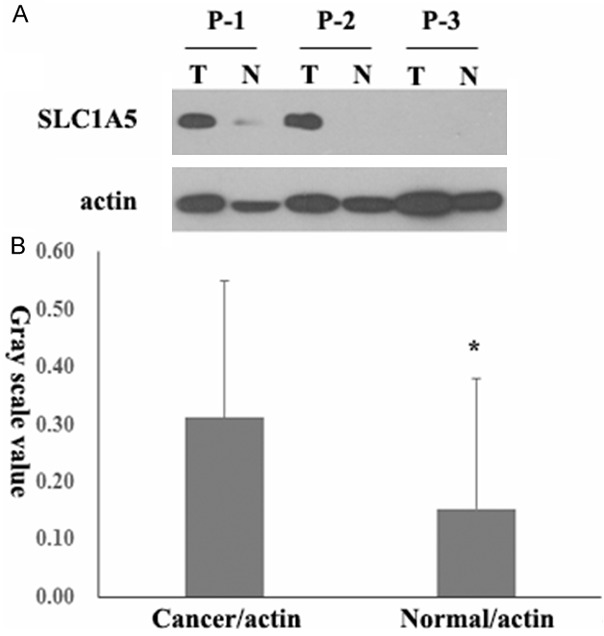

To avoid the false positive possibility of immunohistochemical analysis and bias lead by pathologists who scoring the staining intensity, we further collected 12 pairs of fresh cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues from pathologically proven colorectal cancer patients, and evaluated the expression of SLC1A5 biochemically by Western blot. As shown in Figure 2A, SLC1A5 expression increased significantly in colorectal cancer tissues compared with adjacent normal mucosa tissues from the same patient. After gray scale scanning of the immunoreactive bands, the average SLC1A5 expression level in cancer tissues was more than that in adjacent normal mucosa tissues (P < 0.05, Figure 2B). Based on results of immunohistochemistry and Western blot, we demonstrated that SLC1A5 expression was upregulated in human colorectal cancer, which indicates functional importance of SLC1A5 for tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer.

Figure 2.

SLC1A5 expression is upregulated in human colorectal cancer as evidenced by Western blot. A. 12 pairs of fresh colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues were collected and analyzed for SLC1A5 protein expression by Western blot. 4 representative pairs of tumor (T) and normal (N) tissues were shown, β-actin was used as loading control. B. Statistics of gray scanning scales of SLC1A5/β-actin in 12 pairs of colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues were shown, statistical significance was assessed by Student t test and denoted as *, P < 0.05.

Correlations between SLC1A5 expression and patient clinical factors

Enhanced expression of SLC1A5 and clinical significance was reported in different cancer types, we further validated the clinical relevance of SLC1A5 in our cohort. Statistical correlation was evaluated between SLC1A5 stainingscore and patient clinical parameters including gender, TNM stage and histological subtypes from 90 samples in tissue microarray. As shown in Table 3, SLC1A5 expression was correlated with T stage (P = 0.021) and histologicalsubtype (P < 0.001), in addition, M stage seems relevant but couldn’t be considered statistically significant owing to extremely small sample size.

Table 3.

Correlations between SLC1A5 expression and patient clinical factors

| SLC1A5 Expression | Cancer n (%) | Normal n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 7 (8) | 25 (28) | < 0.001 |

| Positive | 83 (92) | 65 (72) |

Statistics of correlation between IHC staining scores for SLC1A5 and clinical characteristics of patients in a tissue microarray containing 90 pairs of primary colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues. Statistical significance was assessed by Likelihood Ratio test and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

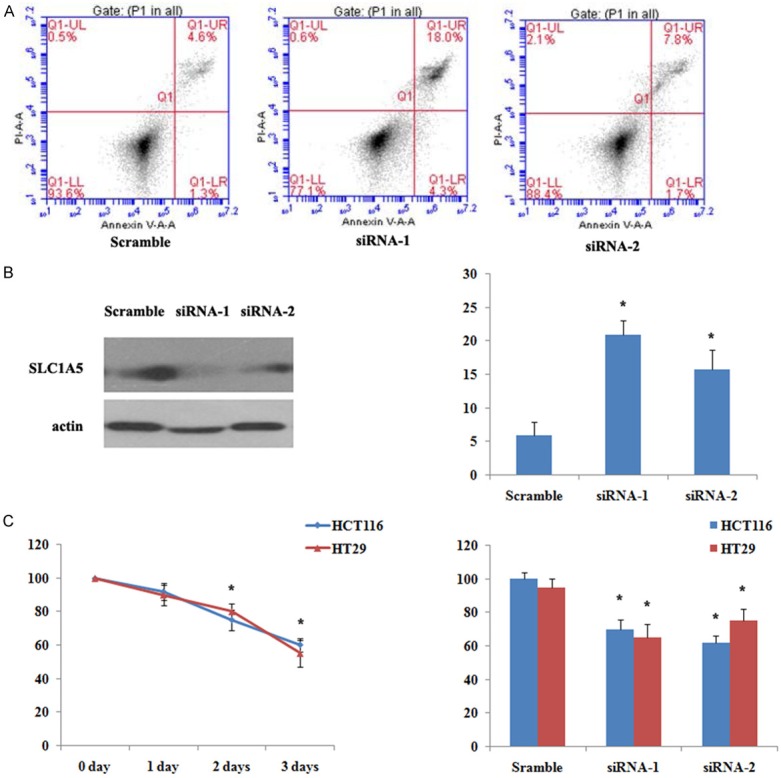

Attenuation of SLC1A5 expression inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis

SLC1A5 is the major glutamine transporter in cancer cells, and many studies showed that SLC1A5 plays an important role in cancer cell survival and proliferation. To evaluate the functional importance of SLC1A5 in colorectal cancer cell, we used synthetic siRNA to attenuate SLC1A5 expression in human colorectal cancer cell lines HT29 and HCT116, and evaluate cell proliferation and apoptosis. As shown in Figure 3B, two synthetic siRNA reduced SLC1A5 expression after transfection. Following starvation for 6 hours, two synthetic siRNA both induced typical apoptosis as evidenced by increase in Annexin V positive population (Figure 3A, 3B) by flow cytometry, in contrast scramble siRNA group had no such effect. After starvation and transfection of synthetic siRNA of SLC1A5, we observed cell growth were inhibited while treating time prolonged as evidenced by MTT assay, and two synthetic siRNA both worked efficiently compared with scramble siRNA in HT29 and HCT116 cells (Figure 3C). Thus enhanced SLC1A5 expression might provide a survival and growth advantage in colorectal cancer cells, and indicates the potential chance to treat colorectal cancer by targeting glutamine transporters such as SLC1A5.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of SLC1A5 expression inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis. A. Representative cell apoptosis detected with Annexin V/PI double staining by flow cytometry. HCT116 cells were starved for 6 hours before transfection of two synthetic siRNA and scramble control siRNA, apoptosis were evaluated after 48 hours. B. Western blot analysis verification of attenuation of SLC1A5 expression in HCT116 cells transfected with siRNA, statistical analysis of apoptosis rate were shown in scramble and anti-SLC1A5 siRNA groups. C. Cell proliferation evaluated by MTT assay. HCT116 and HT29 cells were starved for 6 hours before transfection of two synthetic siRNA and scramble control siRNA, MTT assay were done after 24, 48 and 72 hours, and statistical analysis were shown on the right panel. All of the above data are shown as mean ± SD and represent 3 independent experiments, statistical significance was assessed by Student t test and denoted as *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

Transport of amino acid across the plasma membrane is mediated by integral membrane transport systems including system A, ASC, N and L according to their substrate specificity [13]. The amino acid transporters are further categorized in different gene families based on sequence homology, system ASC transporters belong to solute carrier family (SLC1) which have high affinity to glutamine and neutral amino acids, among which, SLC1A5 plays an important role in glutamine transport in various cancer cells [14].

Enhanced expression of SLC1A5 and clinical significance was reported in different cancer types [11,12,15,16]. Recently Shimizu et al reported in non-small cell lung cancer that SLC1A5 expressed in 66% of patients using tissuemicroarray, and SLC1A5 expression was closely correlated with disease stage and identified as an independent biomarker for poor survival [15]. Witte et al. have reported SLC1A5 expression status in 64 colorectal cancer patients by IHC analysis, they showed that SLC1A5 staining was positive in 59% of the cases, and SLC1A5 staining was negative correlated with patient survival [11]. However, there is no convincing data comparing SLC1A5 expression in human colorectal cancer with normal colorectal mucosa, using immunohistochemical analysis of tissue microarrays containing 90 pairs of primary colorectal cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues, we demonstrated for the first time that SLC1A5 expression was upregulated significantly in colorectal cancer (P < 0.001). We further validated SLC1A5 expression by Western blot in 12 pairs of fresh cancer and adjacent normal mucosa tissues, and proved SLC1A5 overexpression in colorectal cancer (P < 0.05). In our cohort, we found that SLC1A5 expression was correlated with T stage (P = 0.021), indicating the functional importance of SLC1A5 in colorectal tumorigenesis. However, we didn’t find any correlation of SLC1A5 expression with patient survival (data not shown), which is at variance with previous reports, possibly owing to relatively small sample size or heterogeneity of population characteristics.

Glutamine is a nonessential amino acid at normal conditions, however it becomes conditional essential in cancer cells as the demand can often exceed the availability. Cancer cells differ in their need for exogenous glutamine, ranging from completely dependence called “glutamine addiction” to totally independence probably owing to de novo glutamine synthesis [17,18]. Recent studies revealed novel functions of glutamine independent of the metabolic role to sustain cellular growth and survival signaling pathway including mTOR and ERK [19,20]. Since SLC1A5 is mainly responsible for glutamine transport in cancer cells, emerging functional studies indicate SLC1A5 inhibition could retard cancer cell growth and survival [7,8]. Preliminary results by Pawlik et al. showed that glutamine transport inhibitor Phorbol esters could attenuate growth in human colon carcinoma cells [21], however there is no direct evidence indicate functional importance of SLC1A5 in colorectal cancer. We used synthetic siRNA to attenuate SLC1A5 expression in human colorectal cancer cell lines, and found that SLC1A5 downregulation significantly inhibited cell proliferation and induce typical hallmarks of apoptosis. Therefore, the contribution of SLC1A5 to glutamine transport in colorectal cancer cells is significant, and enhanced expression of SLC1A5 might provide survival advantage for colorectal cancer cells.

Interestingly, SLC1A5 expression in tubular adenocarcinoma is significantly higher than mucinous adenocarcinoma in this cohort (P < 0.001), which is in accordance with our previous report that enhanced GLS1 (a major enzyme in glutaminolysis) in tubular adenocarcinoma but not in signet-ring cell and mucinous adenocarcinoma subtypes [6]. These result indicate that mucinous adenocarcinoma have distinct glutamine metabolic pathways from the more common tubular adenocarcinoma subtype. Recently glutamine based PET scan is an alternative choice for tumors with low glucose metabolism due to its better sensibility of certain poorly differentiated carcinomas [22,23]. However, our study found that mucinous adenocarcinoma has low or no expression of SLC1A5 and GLS1, which should be taken into account when glutamine based PET scan is used in colorectal cancer. In addition, therapies targeting glutamine metabolic pathway might be useless in signet-ring cell and mucinous adenocarcinoma subtypes owning to their distinct metabolic profiles.

In conclusion, our results provide for the first time the differential expression in human cancer and normal tissues, and a functional link between SLC1A5 expression and growth and survival of colorectal cancer, making it an attractive target in colorectal cancer treatment. Despite emerging studies emphasized SLC1A5 expression and its functional importance in colorectal cancer, further studies are stilled needed. The molecular mechanism of SLC1A5 overexpression and colorectal tumorigenesis remains elusive, and the prognostic value of SLC1A5 needs to be validated in a larger population.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81101507) to Fang Huang and by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81172152) to Tao Zhang.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hohla F, Winder T, Greil R, Rick FG, Block NL, Schally AV. Targeted therapy in advanced metastatic colorectal cancer: current concepts and perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6102–6112. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hensley CT, Wasti AT, DeBerardinis RJ. Glutamine and cancer: cell biology, physiology, and clinical opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3678–3684. doi: 10.1172/JCI69600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuneva MO, Fan TW, Allen TD, Higashi RM, Ferraris DV, Tsukamoto T, Mates JM, Alonso FJ, Wang C, Seo Y, Chen X, Bishop JM. The metabolic profile of tumors depends on both the responsible genetic lesion and tissue type. Cell Metab. 2012;15:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JB, Erickson JW, Fuji R, Ramachandran S, Gao P, Dinavahi R, Wilson KF, Ambrosio AL, Dias SM, Dang CV, Cerione RA. Targeting mitochondrial glutaminase activity inhibits oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang F, Zhang Q, Ma H, Lv Q, Zhang T. Expression of glutaminase is upregulated in colorectal cancer and of clinical significance. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1093–1100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassanein M, Hoeksema MD, Shiota M, Qian J, Harris BK, Chen H, Clark JE, Alborn WE, Eisenberg R, Massion PP. SLC1A5 mediates glutamine transport required for lung cancer cell growth and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:560–570. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Beaumont KA, Otte NJ, Font J, Bailey CG, van Geldermalsen M, Sharp DM, Tiffen JC, Ryan RM, Jormakka M, Haass NK, Rasko JE, Holst J. Targeting glutamine transport to suppress melanoma cell growth. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1060–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Liu Y, Shen X, Zhang X, Chen X, Yang C, Gao H. The PIWI protein acts as a predictive marker for human gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:315–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang F, Nie C, Yang Y, Yue W, Ren Y, Shang Y, Wang X, Jin H, Xu C, Chen Q. Selenite induces redox-dependent Bax activation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witte D, Ali N, Carlson N, Younes M. Overexpression of the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2555–2557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li R, Younes M, Frolov A, Wheeler TM, Scardino P, Ohori M, Ayala G. Expression of neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human prostate. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3413–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J, Zorzano A. Molecular biology of mammalian plasma membrane amino acid transporters. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:969–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: partners in crime? Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu K, Kaira K, Tomizawa Y, Sunaga N, Kawashima O, Oriuchi N, Tominaga H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Yamada M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. ASC amino-acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) as a novel prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2030–2039. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younes M, Pathak M, Finnie D, Sifers RN, Liu Y, Schwartz MR. Expression of the neutral amino acids transporter ASCT1 in esophageal carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:3775–3779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kung HN, Marks JR, Chi JT. Glutamine synthetase is a genetic determinant of cell type-specific glutamine independence in breast epithelia. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Heuvel AP, Jing J, Wooster RF, Bachman KE. Analysis of glutamine dependency in non-small cell lung cancer: GLS1 splice variant GAC is essential for cancer cell growth. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:1185–1194. doi: 10.4161/cbt.21348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duran RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, Heiserich L, Skendaj R, Gottlieb E, Hall MN. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell. 2012;47:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicklin P, Bergman P, Zhang B, Triantafellow E, Wang H, Nyfeler B, Yang H, Hild M, Kung C, Wilson C, Myer VE, MacKeigan JP, Porter JA, Wang YK, Cantley LC, Finan PM, Murphy LO. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawlik TM, Souba WW, Sweeney TJ, Bode BP. Phorbol esters rapidly attenuate glutamine uptake and growth in human colon carcinoma cells. J Surg Res. 2000;90:149–155. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu W, Zha Z, Ploessl K, Lieberman BP, Zhu L, Wise DR, Thompson CB, Kung HF. Synthesis of optically pure 4-fluoro-glutamines as potential metabolic imaging agents for tumors. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1122–1133. doi: 10.1021/ja109203d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman BP, Ploessl K, Wang L, Qu W, Zha Z, Wise DR, Chodosh LA, Belka G, Thompson CB, Kung HF. PET imaging of glutaminolysis in tumors by 18F-(2S,4R)4-fluoroglutamine. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1947–1955. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.093815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]