Abstract

Objectives: We aimed to determine the predictive factors for central compartment lymph node metastasis (LNM) in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC). The outcome of the current study could assist greatly in decision-making regarding further treatment. Methods: Retrospective analysis of PTMC treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. The predictive risk factors for central lymph node metastases (CLNM) were analyzed with respect to age, sex, tumor size, multifocal and capsular affection. Results: CLNM are common in thyroid microcarcinoma patients. The factors correlated with neoplasm size greater than 5 mm (odds ratio, 0.520; P = 0.001), tumor bilateral (odds ratio, 0.342; P = 0.020), and capsule invasion (odds ratio, 2.539; P = 0.000) were independently predictive of CLNM. In patients with a solitary primary tumor, tumor location in the lower third of the thyroid lobe was associated with a higher risk of CLNM. Conclusions: The risk factors such as male gender, tumor size > 5 mm, bilateral, multifocal location, lower third of the thyroid lobe and capsule invasion that can be identified preoperatively or intraoperatively, be considered for determination of prophylactic CLND in patients with PTMC.

Keywords: Papillary thyroid carcinoma, thyroid microcarcinoma, central lymph node, lymph node dissection, lymph node metastases

Introduction

Thyroid microcarcinoma (TMC) is defined as a malignant tumor measuring 1 cm or smaller in diameter [1]. With the advent of improved methods of diagnostic imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imagingand ultrasonography, the diagnosis of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) has been increased [2]. The treatment may vary from follow-up without surgery to a total thyroidectomy with or without radioactive iodine treatment. Although PTMC has an indolent course, the cervical lymph node metastasis (CLNM) of PTMC was reported in 12.3 to 64.1 per cent of patients and has been known to be associated with locoregional recurrence and distant metastasis [3,4]. The role of central lymph node dissection (CLND) for PTMC has been debated because no evidence has demonstrated that CLND has better prognostic benefit. In addition, CLND can increase the frequency of postoperative transient hypocalcaemia. However, better knowledge about the risk factors for CLNM may guide clinical decisions regarding which cases require CLND. Therefore, we investigated predictive factors for CLNM in PTMC using a large group of Chinese patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and surgical treatment

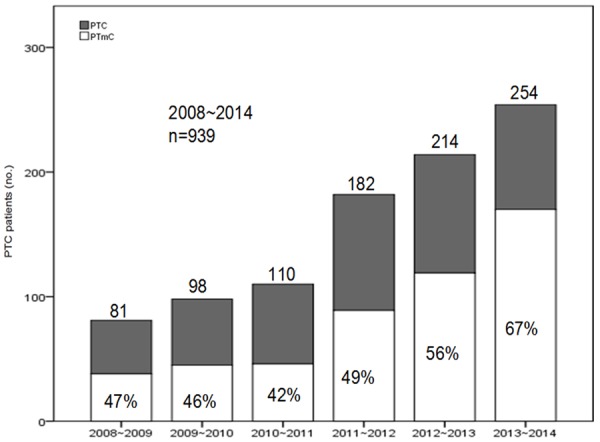

There were 939 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) initially treated at the Department of Thyroid and Breast Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University between January 2008 and January 2014; of these, 507 were diagnosed with PTMC histologically. During the first year of the study (2008~2009), PTMC accounted for 47% of PTC cases treated. However, during subsequent years, while the proportion of PTMC treated have progressively risen from 47% in 2008~2009 to 67% in 2013~2014, the total numbers of PTC patients has also varied over the years (Figure 1). These 507 patients represented 54% of the 939 patients with PTC (of all tumor sizes) who had their initial surgical therapy in our hospital over this time period. The characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Frequency of PTM diagnoses during six years of the follow up. The numbers shown represent all PTC diagnosed during each year; percentages signify proportions of PTMC diagnosed during each year.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of patients (n = 507)

| Number of patients (n) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 412 | 81.3 |

| Male | 95 | 18.7 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| Mean | 45.4 ± 11.2* | |

| < 45 | 234 | 46.2 |

| ≥ 45 | 273 | 53.8 |

| Tumour size (mm) | ||

| ≤ 5 mm | 261 | 51.5 |

| > 5 mm | 246 | 48.5 |

| Bilaterality | ||

| Yes | 120 | 23.7 |

| No | 387 | 76.3 |

| Multifocality | ||

| Yes | 147 | 29.0 |

| No | 360 | 71.0 |

| Thyroid capsular invasion | ||

| Yes | 165 | 32.5 |

| No | 342 | 67.5 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Incidental | 398 | 78.5 |

| Nonincidental (clinically suspected) | 109 | 21.5 |

Mean value ± standard deviation.

CLNM, central lymph node metastasis.

The medical records of all patients with a final pathological report of PTMC were reviewed ret rospectively. Our database included age at the time of surgery, gender, surgical procedure performed, clinical characteristics and final pathology results, including bilaterality, multifocality, cervical lymph node involvement and capsule invasion. The location of the tumor within the gland was classified by which fourth of the thyroid lobe was involved (inferior, middle, superior, or isthmus). The association between primary tumor location and CLNM risk was analyzed using data from 305 patients with solitary primary lesions limited to one lobe. There were 110 patients with a primary lesion in the upper third of the thyroid lobe, 101 patients in the middle third, and 89 patients in the lower third (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of factors on cervical lymph node metastases in patients with PTMC (n = 402)

| Variable | CLNM number (%) | Rate of metastasis (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 117 of 323 (36.2) | 29.1 | 0.032 |

| Male | 39 of 79 (49.4) | 9.7 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| < 45 | 83 of 192 (43.2) | 20.6 | 0.082 |

| ≥ 45 | 73 of 210 (34.7) | 18.2 | |

| Tumour size (mm) | |||

| ≤ 5 mm | 67 of 204 (32.8) | 16.7 | 0.013 |

| > 5 mm | 89 of 198 (44.9) | 22.1 | |

| Location | |||

| Bilateral | 46 of 78 (58.8) | 11.4 | 0.000 |

| Ipsilateral | 110 of 324(34.0) | 27.4 | |

| Tumor number | |||

| Solitary lesion | 103 of 305 (33.8) | 25.6 | 0.000a |

| Upper third | 26 of 110 (23.6) | 6.5 | 0.028b |

| Middle third | 41 of 101 (40.6) | 10.2 | |

| Lower third | 35 of 89 (39.3) | 8.7 | |

| Isthmus | 1 of 5 (20.0) | 0.2 | |

| Multifocal lesions | 52 of 97 (53.6) | 12.9 | |

| Multifocal in both lobes | 46 of 78 (59.0) | 11.4 | 0.032c |

| Multifocal in affected lobe | 6 of 19 (31.6) | 1.5 | |

| Thyroid capsular invasion | |||

| Yes | 57 of 119 (47.9) | 14.2 | 0.015 |

| No | 99 of 283 (35.0) | 24.6 | |

| Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis | |||

| Abscent | 115 of 315 (36.5) | 28.6 | 0.072 |

| Present | 41 of 87 (47.1) | 10.2 |

PTMC: papillary thyroid microcarcinoma.

The P value means the difference between the group solitary lesion and multifocal lesions.

The P value means the difference among the upper third, middle third, lower third, and isthmus in the group of solitary lesion.

The P value means the difference between the group multifocal in both lobes and in affected lobe in the group of multifocal lesions.

Diagnostic pre operative work-up included: clinical examination, chest X-ray, neck and thyroid ultrasonography (US), elastography, and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). During the period of this study, we performed prophylactic CLND for patients without clinical metastatic nodes (cN0). The patients meeting the following conditions could be diagnosed as cN0: 1). No palpable enlarged lymph node in clinical examination or maximumdiameter of enlarged lymph node was less than 2 cm with soft texture; 2). No visible enlarged lymph node in imaging examination or the maximum diameter of enlarged lymph node was less than 1 cm or the maximum diameterwas 1~2 cm with no central liquefaction necrosis, peripheral enhancement or disappeared fat gap adjacent to lymph node. The histology of the frozen sections (FS) guided the extent of the surgical pro cedures. Lobectomy plus psilateral CLND was performed as the initial surgical treatment for PTMC patients with malignant lesions that were limited to a single lobe. When a benign or undetermined nodule was detected in the contralateral lobe by US, a subtotal lobectomy was performed in our hospital. When malignant lesions were found in both lobes of the thyroid by FS, a total thyroidectomy (TT) plus a bilateral CLND was performed.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze the significance of difference in the proportion of variables (univariate analysis). Logistic regression analysis was performed for multivariate analysis to determine significant factors associated with CLNM. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS, Chicago). Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 939 patients diagnosed with PTC, 402 (42.8%) cN0 patients with tumors sized 10 mm or less at the maximum diameter met the inclusion criteria. Of the 402 patients, 79 (16.65%) were men, 323 (83.35%) were women and the male/female ratio was 1/4.1 (Table 2).

The age of these 402 patients ranged from 16 to 78 years (mean 45.4 ± 11.2 years). Based on US and FS results, three different types of surgical procedures were performed: 1) lobectomy with ipsilateral CLND (121 patients); 2) lobectomy + ipsilateral CLND + subtotal lobectomy of the contralateral thyroid lobe (203 patients); 3) TT with a bilateral CLND (78 patients). Mean diameter of PTMC was 0.47 ± 0.17 cm (range, 0.1-1 cm). The characteristics of these 402 patients are listed in Table 2.

Clinicopathologic risk factors

Frequency of CLNM was greater in patients with multifocal neoplasm (P = 0.000), in patients whose tumor size greater than 5 mm (P = 0.000), and in patients with bilateral neoplasm (P = 0.000). Male patients and capsule invasion were also associated with CLNM (P = 0.032 and 0.015, respectively; Table 2). Table 3 shows that there was an increased risk according to the location of the tumor when the location was adjusted for the upper third, which indicates that patients with primary tumor in the lower third had a greater probability of suffering from CLNM than did those with a primary tumor in the upper third. Multivariate analysis showed that neoplasm size greater than 5 mm (odds ratio, 0.520; P = 0.001), tumor bilateral (odds ratio, 0.342; P = 0.020), and capsule invasion (odds ratio, 2.539; P = 0.000) were independently predictive of CLNM (Table 4).

Table 3.

The risk of location in the solitary primary tumor for CLNM adjusted for the factor of upper third

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location upper third | 1 | ||

| Middle third | 2.989 | 1.873~4.345 | 0.001 |

| Lower third | 13.047 | 8.587~20.787 | 0.001 |

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for risk factors of central lymph node metastasis

| 95% CI. for Exp (β) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| P value* | Exp (β)Ψ | Lower | Upper | |

| Gender (male) | .720 | .913 | .556 | 1.500 |

| Size (> 5 cm) | .001 | .520 | .358 | .755 |

| Location (Bilateral) | .020 | .342 | .139 | .845 |

| Multifocal (present) | .820 | .905 | .381 | 2.150 |

| Capsular invasion (present) | .000 | 2.539 | 1.729 | 3.729 |

Logistic regression analysis.

Exp (β): odds ratio for subclinical central lymph node metastasis.

CI: confidence interval.

Complications

Postoperative hypocalcaemia was defined as at least 1 event of hypocalcemic symptoms (perioral numbness, or paresthesia of hands and feet) or at least 1 event of biochemical hypocalcaemia (ionized Ca level < 1.0 mmol/L or total Ca level < 8.0 mg/dL). Among 402 patients, transient hypocalcaemia developed in 28 (6.97%) patients, and resolved within 6 months. Permanent hypocalcaemia developed in 3 patients (0.75%). Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury occurred in 5 patients (1.24%). 4 of these 5 cases was transient, and 1 of the 5 cases were permanent. Postoperative hematoma developed in 2 patients (0.50%) and was treated by reoperation.

Follow-up

All patients received TSH-suppressive hormonal therapy after surgery and thyroxine doses were adjusted to risk (to keep TSH below 0.1 mU/L for high-risk patients and from 0.1 to 0.3 mU/L for low-risk patients). Radioactive iodine therapy was not routinely prescribed for patients in this study because of its strictly controlled use in China. Radioactive iodine therapy was given following thyroxine withdrawal to selected patients with positive lymph nodes on pathology or who had distant metastasis. A routine periodic clinical examination (every 3 months in the initial year and then at yearly intervals) was mandatory, including neck ultrasound, whole body scans and serum TSH and basal thyroglobulin (Tg) levels with measurement of Tg antibodies.

Excluding 170 patients who were diagnosed with PTMC during 2013~2014, 232 patients adhered to a 12-month follow-up period, and many patients had a longer follow-up period. The mean length of follow-up was 28.5 months. The following criteria were used to define disease recurrence: either pathological evidence of disease on excision or cytology or recurrent disease confirmed by two surveillance modalities (e.g. elevated Tg and whole-body scan). During the follow-up period, there were no recurrences in central cervical compartment (level VI). Only 3 patients who underwent lobectomy with ipsilateral CLND (0.75%) suffered from a malignant recurrence in the contralateral lobe. This recurrence was resected; no patient demonstrated distant metastasis or died.

Discussion

The incidence of PTMC has been increasing in China and over the world with the advent of improved methods of diagnostic imaging. PTMCs account for nearly 50% of new cases of PTC [5]. Although the reasons for the rapid increase vary extensively, more and more studies have shown that papillary thyroid microcarcinomas (PTMC) account for a significant proportion of the increase [6]. An interesting finding of our study was that the proportion of PTMC treated have progressively risen from 47% in 2008~2009 to 67% in 2013~2014. The high incidence rate since 2012 may be attributed to the elastography for the evaluation of thyroid nodules. Presently, thyroid nodules areoften diagnosed in asymptomatic patients with many of these nodules frequently presenting as nonpalpable lesions. More than 60% of the population will present with thyroid nodules if screened with cervical ultrasonography. Elastography is a promising new technique that may improve the ultrasonic evaluation of thyroid nodules [7]. This technology evaluates tissue stiffness. Malignant lesions tend to be stiffer than the surrounding benign tissues. Elastography has been easily integrated into a routine ultrasound examination in our hospital since 2012.

Despite the overall prognosis of PTMC is general excellent, CLNM for some patients still exists. CLNM are usually identified only when prophylactic Level VI area lymph node dissection is performed. Wada et al. [8] reported that as high as 64% of all PTMCs had central node involvement after they followed a group of 259 patients, all of whom underwent lymph node dissection at the time of thyroidectomy. CLNM have previously been associated with tumor stage [9], increased risk of neoplastic progression [10], and were characterized as the most important prognostic factors for patients operated on for TMC [11,12]. In our study, 156 patients had cervical lymph node metastases, representing 38.8% of all 402 patients. This percentage leads us to suggest that PTMC is not an indolent disease.

The opinion that patients with lymph node metastasis proved by physical examination or radiological findings must be performed lymphadenectomy has come to a consensus. Routine prophylactic CLND for PTMC has been debated because prophylactic CLND seems to have little prognostic benefit [13,14]. CLNM, however, is an important risk factor of locoregional recurrences and often is not detected clinically. It is relatively difficult to reoperate on patients with regional recurrence in the central compartment. In addition, the central compartment can be dissected during thyroid surgery as it does not extend the wound. Therefore, investigation of the clinicopathologic factors associated with subclinical CLNM is of clinical importance. A variety of studies have been focused on the influencing factors of cervical lymph node metastases [15,16]. Our analyses of influencing factors of cervical lymph node metastases in patients with TMC found that: The factors correlated with neoplasm size greater than 5 mm (odds ratio, 0.520; P = 0.001), tumor bilateral (odds ratio, 0.342; P = 0.020), and capsule invasion (odds ratio, 2.539; P = 0.000) were independently predictive of CLNM. In patients with a solitary primary tumor, tumor location in the lower third of the thyroid lobe was associated with a higher risk of CLNM. Patient age is known to be a significant prognostic factor, but in our study, age was not predictive of CLNM; frequency of subclinical CLNM was slightly greater in patients aged < 45 years. Previous studies suggested that the location of PTMC within the thyroid was related to the prevalence of CLNM [17,18]. In our study of patients with a solitary primary tumor, we found that location in the lower third of thyroid lobe conferred a higher risk for CLNM. These results suggest that CLND may not be necessary for patients with only one tumor located in the upper third of the thyroid.

A meta-analysis on the safety of central lymph node dissection with total thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma was performed by Pan Y et al. [19]. A total of 1524 patients were included, 620 were with total thyroidectomy plus central lymph node dissection and 904 with thyroidectomy alone. In their study, there was a significant increased risk of temporary hypocalcaemia and temporary vocal cord palsy when central lymph node dissection was performed in addition to a thyroidectomy. However, the risk of permanent hypocalcaemia and permanent vocal cord palsy has no statistical difference between the two groups. Recent studies of CLND report the development of permanent hypoparathyroidism in 0~4% of patients and the development of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury in 0~6% of patients, respectively; the temporary complication rates for these conditions were 47 and 5%, respectively[20,21]. Hence, the advantage of prophylactic CLND should be weighed against the associated complications. In our study, permanent hypocalcaemia developed in 3 patients (0.75%). Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury occurred in 5 patients (1.24%). 4 of these 5 cases was transient, and 1 of the 5 cases were permanent. It suggests that routine CLND can be performed safely and with low morbidity by experts. Moreover, parathyroid autotransplantation was effective to reduce the complications related to parathyroid glands.

In our study, there were no recurrences in the central cervical compartment, which may results from effective removal of central LNM by CLND. We cannot, however, exclude the influence of short-term follow-up analysis in this study. This study does not address how to integrate ablative therapies such as radioiodine ablation into the treatment algorithm for patients with PTMC. Certainly, many centers have developed excellent local tumor control with such therapies. In our study, radioactive iodine therapy was not routinely prescribed for PTMC patients after surgery because of its strictly controlled use in China. Once the metastatic or recurrent lesions were detected, either surgical treatment or radioactive iodine therapy was suggested.

Conclusion

Taken together, though PTMC is generally associated with an excellent prognosis, patients may die of PTMC. The management of central lymph node is important in PTMC because recurrence of the central compartment can result in a serious problem such as invasion of the recurrent laryngeal nerve or trachea. Given these observations, it is hypothesized that a prophylactic CLND at the time of the original thyroidectomy would decrease the likehood of cervical disease remaining. In addition, the risk factors such as male gender, tumor size > 5 mm, bilateral, multifocal location, lower third of the thyroid lobe and capsule invasion that can be identified preoperatively or intraoperatively, be considered for determination of prophylactic CLND in patients with PTMC.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hedinger C, Sobin LH. Histologic typing of thyroid tumours. In: Hedinger C, Williams ED, Sobin LH, editors. International histological classification of tumours. 2nd edn. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988. pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kent WD, Hall SF, Isotalo PA, Houlden RL, George RL, Groome PA. Increased incidence of differentiated thyroid carcinoma and detection of subclinical disease. CMAJ. 2007;177:1357–61. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KJ, Cho YJ, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Kim JG, Ahn CJ, Lee DH. Analysis of the clinicopathologic features of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma based on 7-mm tumor size. World J Surg. 2011;35:318–323. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0886-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay ID, Hutchinson ME, Gonzalez-Losada T, McIver B, Reinalda ME, Grant CS, Thompson GB, Sebo TJ, Goellner JR. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 900 cases observed in a 60-year period. Surgery. 2008;144:980–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soares P, Celestino R, Gaspar da Rocha A, Sobrinho-Simões M. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: how to diagnose and manage this epidemic? Int Surg Pathol. 2014;22:113–9. doi: 10.1177/1066896913517394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abboud B, Daher R, Sleilaty G, Abadjian G, Ghorra C. Are papillary microcarcinomas of the thyroid gland revealed by cervical adenopathy more aggressive? Am Surg. 2010;76:306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro-pla D. Ultrasound elastography in the evaluation of thyroid nodules for thyroid cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:1–5. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835a87c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada N, Duh QY, Sugino K, Iwasaki H, Kameyama K, Mimura T, Ito K, Takami H, Takanashi Y. Lymph node metastasis from 259 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: frequency, pattern of occurrence and recurrence, and optimal strategy for neck dissection. Ann Surg. 2003;237:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055273.58908.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimm O, Ukkat J, Dralle H. Determinative factors of biochemical cure after primary and reoperative surgery for sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg. 1998;22:562–8. doi: 10.1007/s002689900435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellegriti G, Scollo C, Lumera G, Regalbuto C, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Clinical behavior and outcome of papillary thyroid cancers smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter: study of 299 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3713–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peixoto Callejo I, Americo Brito J, Zagalo CM, Rosa Santos J. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: multivariate analysis of prognostic factors influencing survival. Clin Transl Oncol. 2006;8:435–43. doi: 10.1007/s12094-006-0198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombardi CP, Bellantone R, De Crea C, Paladino NC, Fadda G, Salvatori M, Raffaelli M. Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastases, and risk factors for recurrence in a high prevalence of goiter area. World J Surg. 2010;34:1214–21. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada N, Duh QY, Sugino K, Iwasaki H, Kameyama K, Mimura T, Ito K, Takami H, Takanashi Y. Lymph node metastasis from 259 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: frequency, pattern of occurrence and recurrence, and optimal strategy for neck dissection. Ann Surg. 2003;237:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055273.58908.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noguchi S, Yamashita H, Uchino S, Watanabe S. Papillary microcarcinoma. World J Surg. 2008;32:747–53. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9453-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roh JL, Kim JM, Park CI. Central cervical nodal metastasis from papillary thyroid microcarcinoma:pattern and factors predictive of nodal metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2482–2486. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwak JY, Kim EK, Kim MJ, Son EJ, Chung WY, Park CS, Nam KH. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: predicting factors of lateral neck node metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1348–55. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Wei WJ, Ji QH, Zhu YX, Wang ZY, Wang Y, Huang CP, Shen Q, Li DS, Wu Y. Risk factors for neck nodal metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 1066 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1250–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada N, Duh QY, Sugino K, Iwasaki H, Kameyama K, Mimura T, Ito K, Takami H, Takanashi Y. Lymph node metastasis from 259 papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: frequency, pattern of occurrence and recurrence, and optimal strategy for neck dissection. Ann Surg. 2003;237:399–407. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055273.58908.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan Y, Zheng Q, Fan Y, et al. Safety of thyroidectomy combined with central lymph node dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Chin J Gen Surg. 2010;25:631–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moo TA, Umunna B, Kato M, Butriago D, Kundel A, Lee JA, Zarnegar R, Fahey TJ 3rd. Ipsilateral versus bilateral central neck lymph node dissection in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:403–408. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b3adab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koo BS, Choi EC, Yoon YH, Kim DH, Kim EH, Lim YC. Predictive factors for ipsilateral or contralateral central lymph node metastasis in unilateral papillary thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;249:840–844. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a40919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]