Abstract

Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, African immigrants have worse cancer outcomes. However, there is little research about cancer behaviors and/or interventions in this growing population as they are generally grouped with populations from America or the Caribbean. This systematic review examines cancer-related studies that included African-born participants. We searched PsychINFO, Ovid Medline, Pubmed, CINHAL, and Web of Science for articles focusing on any type of cancer that included African-born immigrant participants. Twenty articles met study inclusion criteria; only two were interventions. Most articles focused on one type of cancer (n=11) (e.g., breast cancer) and were conducted in disease-free populations (n=15). Studies included African participants mostly from Nigeria (n=8) and Somalia (n=6). However, many papers (n=7) did not specify nationality or had small percentages (<5%) of African immigrants (n=5). Studies found lower screening rates in African immigrants compared to other subpopulations (e.g. US born). Awareness of screening practices was limited. Higher acculturation levels were associated with higher screening rates. Barriers to screening included access (e.g. insurance), pragmatic (e.g. transportation), and psychosocial barriers (e.g. shame). Interventions to improve cancer outcomes in African immigrants are needed. Research that includes larger samples with diverse African subgroups including cancer survivors are necessary to inform future directions.

Introduction

African born immigrants are one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the US; increasing from 881,300 in 2000 to 1,606,914 by 2010.1 The majority of African immigrants come from Western (35.71%) and Eastern Africa (29.612%). Specific top countries of origin include Nigeria (13.65%), Ghana (7.76%), Ethiopia (10.80%), and Kenya (5.51%).2 More than half of the African immigrants arrived recently to the US. Thus, there has been limited research on African immigrant health, and it has mostly focused on infectious diseases (e.g. tuberculosis, HIV) while chronic diseases, such as cancer, have been understudied.3

Previous research has shown disparities among US and immigrant populations in cancer information,4 screening rates,5–10 early diagnosis,11 quality of care,12 receipt of recommended treatment,11,12 and survival outcomes.13 Identified barriers to access health services include access to care factors (e.g. insurance, citizenship status),14–16 pragmatic factors (e.g. language difficulties),16 and psychosocial factors (e.g. limited knowledge, embarrassment and fear of screening procedures, cultural beliefs).10,17–19 Having a usual source of care,8,20,21 provider recommendation,20,21 and acculturation,21,22 are some of the identified protective factors that increase the odds of screening in this population.

However, African immigrants are underrepresented in this research. The scarce research that includes African immigrants has shown cancer-related disparities across the cancer control continuum.13,23–28 However, African-born immigrants tend to constitute small percentages of the samples and/or they tend to be lumped with African Americans or Caribbean, or categorized as “African” or “Black foreign-born” without specifying country of origin.4,9,25 The goal of this paper is to offer a systematic literature review of cancer studies that include African-born populations to suggest venues for further research and interventions that can be implemented in the US.

Methods

Search Strategy

The research team participated on a literature search course conducted by a librarian at Georgetown University. The course included strategies for conducting searches (e.g. selecting, exploding, and combining medical subject heading terms- MeSH terms) as well as the particularities of different search engines (e.g. Ovid, CINHAL). The authors followed the guidelines outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA).29,30

Identification of Studies

We searched PsychINFO, Ovid Medline, Pubmed, CINHAL, and Web of Science for papers on any type of cancer (including disease free) with African-born immigrant participants. The search was conducted in May 1, 2013. We used the following search terms: “cancer” and “African immigrant” to find the appropriate MeSH terms within each search engine. For the cancer keyword we used neoplasm as a MeSH term in all search engines. However, “African immigrant” elicited different MeSH terms in the various search engines. We developed specific search strategies for each search engine to maximize the number of papers retrieved without losing the population target. For instance, when typing African Immigrants in Psychinfo we obtained several MeSH terms including: Immigration, Blacks, and African cultural groups. After examining the scope and the papers retrieved we realized that Black referred to African Americans whereas African cultural groups referred to the cultural groups from Continental Africa. Combining “immigrant” and “African cultural groups” and “neoplasms” yielded fewer results (n= 5), so we decided to use African cultural groups in combination with neoplasm (n=11). We used “African cultural groups” in Psychinfo, “African continental ancestry group” in combination with “emigrants and immigrants” in Ovid Medline, “African” in CINHAL, “African immigrant” in Pubmed, and “African” combined with “immigrant” in Web of Science. An exemplary search with Psychinfo is provided in Table 1. We additionally included other papers retrieved from the reference list of the selected papers and others suggested by scholars. References were imported to Refworks to delete duplicates.

Table 1.

Psych-Info Search

| Steps | Search Terms | Number of Retrieved Papers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exp Neoplasms/ | 31295 |

| 2 | Exp African Cultural Groups/ | 1020 |

| 3 | Exp Immigration/ | 12807 |

| 4 | (African Cultural Groups and Immigration). | 77 |

| 5 | (Neoplasms and (African Cultural Groups and Immigration)) | 5 |

| 6 | (Neoplasms and African Cultural Groups). | 11 |

Exp: exploded terms

Note: Step 6 is bolded to highlight the search we used

Review and Abstraction Process

First, two members of the research team (AH and MS) independently reviewed all the abstracts and categorized the papers based on whether they met the inclusion criteria (i.e. Yes, No, and Maybe). In the second round of review, the two members of the team independently reviewed the full text articles categorized as “Maybe” to further determine eligibility. Discrepancies were solved by discussion until consensus was reached (AH, MS) and a third researcher was consulted (VS) to resolve disagreements. We developed a data abstraction document to capture the information from the studies that met the eligibility criteria (e.g. sample characteristics, main outcomes, main results). Two members of the research team conducted the data abstraction (AH, MS).

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Retrieved papers were eligible if they addressed (1) any type of cancer and included (2) African-born immigrant populations in the sample. No year, language, or study location limits were added in the search. We did not set a threshold for the number or percent of African-born persons in study samples. Case studies, review papers, and epidemiological studies outside the US were excluded.

Results

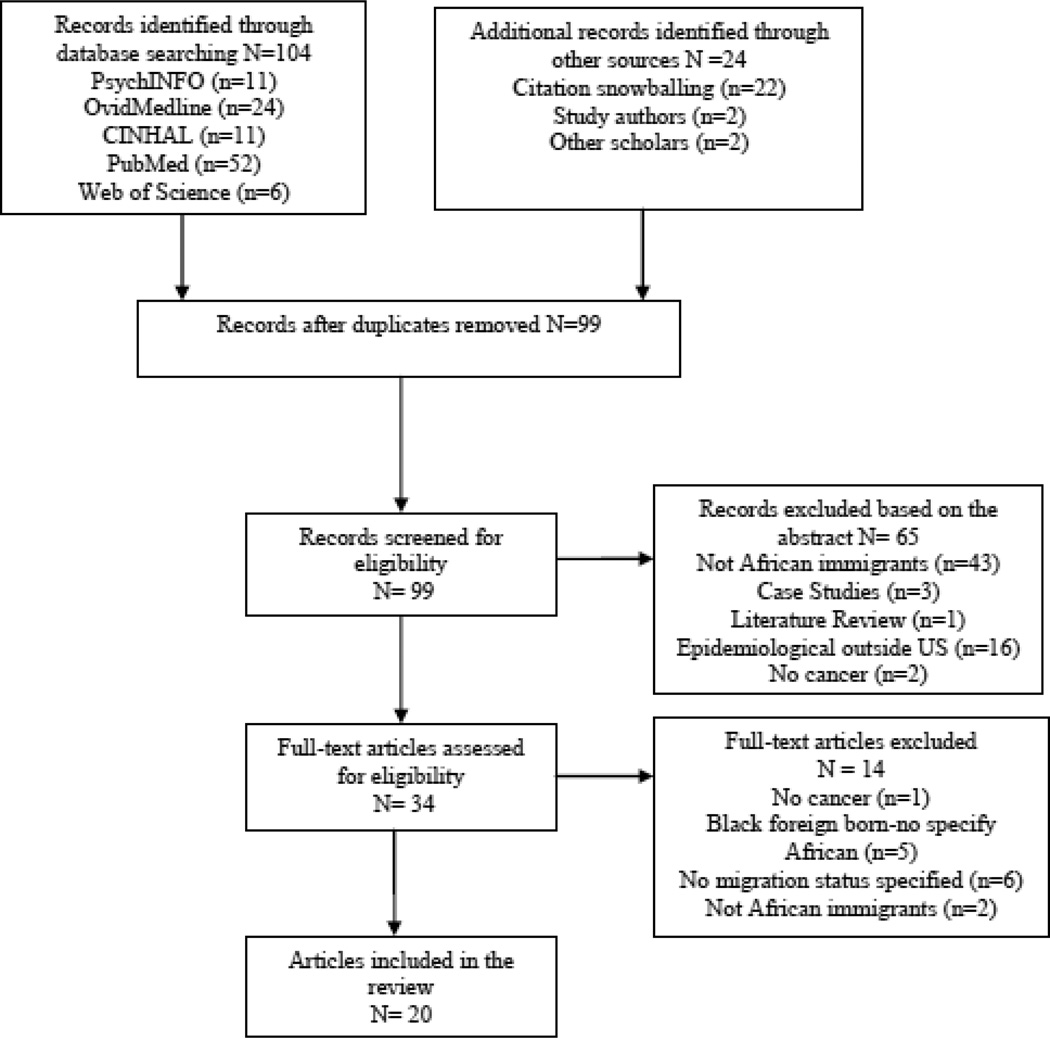

The five search engines yielded a total of 104 records, and 24 additional records were identified through the list of references, scholars, and study authors. After deleting duplicates, 99 records were screened for eligibility. A total of 20 papers met inclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for additional details). Although English language was not an inclusion criteria, all the articles that met the eligibility criteria were written in English.

Figure 1.

Articles Identified and Screened for Eligibility

Most papers focused on a single type of cancer (55%) and breast, cervical, and prostate were the most common among those studies. The majority of the studies were conducted with disease free samples (75%). Half used quantitative methods (50%) and there were only two intervention studies. 31,32 Most research focused on women only (60%), and Nigerians (40%) and Somalis (30%) were the most represented nationalities in the articles. However, a significant number of studies (35%) did not specify nationality or had African immigrant samples (25%) that were less than 5% of the total sample, so no specific results about African immigrants were reported (see Table 2 for summary description). The retrieved main findings from studies are summarized below based on the type of cancer and in relation to the cancer control continuum (see Table 3 for paper’s description).

Table 2.

Summary Characteristics of Cancer-related Papers that include African Immigrant Samples

Note: AI: African immigrants

Table 3.

Description of Cancer-related Papers that include African Immigrant Samples

| Authors/y Ear |

Setting | Sample | Study Design | Type of cancer |

Type of population |

Types of outcomes |

Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdullahi et al., 2009 | UK Urban Community outreach |

Total N=50 AI = 50 (100%) (Somalia) Gender: women Age: 25–64 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in UK: 88% ≥ 4 years |

Qualitative (focus groups/ interviews ) |

Cervical | Disease-free | Knowledge and barriers to screening |

Limited knowledge of cancer screening and risk factors. Barriers to screening included fatalism, anticipating embarrassment due to female circumcision, fear of the test, language, and pragmatic barriers. Need to provide culturally appropriate education and services. |

| Bache et al., 2012 | UK Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 8 AI = 1(12.5%) (Nigeria) Gender: women and men Age: 35–81 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in UK: 87.5% > 10 |

Qualitative (in depth interviews) |

Multiple (prostate and breast) |

Cancer survivors |

Lay explanations of cancer, coping styles, and experiences with health services |

Lay explanations of cancer were biomedical and cultural. Participants were generally satisfied with their health care. Coping strategies included denial, gaining knowledge, living each day at a time, religious coping, and maintaining a positive attitude. |

| Borrell et al., 2006 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 236 AI = 7 (3%) Gender: women Age: 42 median (foreign born only) Education:22.4% < High school Insurance: not reported Years in US: not reported |

Quantitative Cross- sectional survey |

Breast | Disease-free | Association between nativity and breast cancer risk factors |

U.S.-born blacks were more likely to smoke, not breastfeed, and breastfeed for a shorter duration than foreign-born Blacks (all p < 0.01). No specific findings for African immigrants due to small sample sizes. |

| Carroll et al., 2007 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 34 AI = 34(100%) Somali (Bantu and non-Bantu) Gender: women Age: 18–53 (Median=27) Education: 79% < High school Insurance: not reported Years in US: 30% > 5 years |

Qualitative (interviews) |

Multiple (cervical and breast) |

Disease-free | Beliefs and experiences regarding health promotion and screening |

Participants had limited knowledge about breast and cervical cancer screening services, especially Bantu women. Reasons included lack of familiarity with the health care system, language barriers, fear and stigma. |

| Creque et al., 2010 | US Urban Cancer registry |

Total N= 311 AI = 2 (1%) Gender: women Age:22 ≥71 Education: not reported Insurance: 7.1% uninsured Years in US: not reported |

Quantitative Cohort Study |

Uterine | Cancer survivors |

Survival rates of black women with uterine cancer |

5-yr survival rate slightly higher for US-born black women. Age was predictor of death in US-born women and type of treatment was predictor for foreign-born women. No specific findings for African immigrants due to small sample sizes. |

| Ehiwe et al., 2012 | UK Urban Community outreach |

Total N=53 AI = 53(100%) (Ghana, Nigeria) Gender: women and men Age:20–55 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in UK: 100% 3–5 years |

Qualitative (focus group) |

Unspecifie d |

Disease-free | Perceptions and knowledge about cancer |

Feelings of fear, apprehension, shame, and secrecy were mentioned as barriers to cancer screening, health services seeking, and family communication. |

| Ehiwe et al., 2013 | UK Urban Community outreach |

Total N=53 AI = 53(100%) (Ghana, Nigeria) Gender: women and men Age:20–55 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in UK: 100% 3–5 years |

Qualitative (focus group) |

Unspecifie d |

Disease-free | Perceptions and knowledge about cancer |

Participant’s perceptions of cancer were both biomedical and faith- based. There were diverse opinions in relation to God’s role in the cause and cure of cancer and the effectiveness of African herbal medicine to treat cancer. |

| Harcourt et al., 2013 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 533 (112 breast/421 cervical) AI = 533 (100%): Somali and other AI Gender: women Age: M=52.7, SD=10.1 (breast) M=34.4, SD=13.2 (cervical) Education: 76% ≤ High school (breast) 55% ≤ High school (cervical) Insurance: not reported Years in US: 61% > 5 years (breast) 70% >5 years (cervical) |

Quantitative (cross- sectional survey) |

Multiple (breast and cervical) |

Disease-free | Screening rates and factors associated with screening |

Only 61% and 52% had ever been screened for breast and cervical cancer respectively. Duration of residence in the US and ethnicity were significantly associated with non-screening. Somali immigrants had 5 times greater odds of ever having a mammogram than other AI. Recent immigrants had only 15% and 40% odds of ever having a mammogram and a pap smear compared to more established immigrants. |

| Kumar et al., 2009 | outreach | Total N= 249 AI = 121 (48.6%) (Nigeria) Gender: men Age: 35–79 Education: < High school 19.5% Insurance: not reported Years in US: M=16.9 SD=9.19 |

Quantitative (cross- sectional survey) |

Prostate | Disease Free | Behavioral factors that contribute to prostate cancer mortality and morbidity |

Compared with Nigerians who did not migrate, Nigerian migrants had significantly higher fruit and whole grain intake, higher of purposeful physical activity, lower tobacco use and trans fats intake which may contribute to decreased CaP risk in Nigerian migrants. |

| Lepore et al., 2012 | US Urban List of health insurance beneficiaries |

Total N= 490 AI = 22.6%* Gender: men Age:45–70 Education: 31.3% < High school Insurance: not reported Years in US: not reported |

Quantitative (randomized controlled trial intervention) |

Prostate | Disease Free | Intervention outcomes related to screening |

Compared to the control, the intervention group reported significantly greater knowledge and likelihood of discussing screening with their doctors, and lower decision conflict. No significant differences were found in testing, congruence between testing intention and behavior, or anxiety. |

| Morrison et al., 2012 | US Urban Secondary analysis in a primary care practice database |

Total N= 91,557 AI = 810 (0.9%) (Somalia) Gender: women and men Age: 25–54 (57.8%) (Somali) Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in the US: not reported |

Quantitative (medical records) |

Multiple (breast, cervical, colorectal) |

Disease Free | Factors associated with preventive services including cancer screening |

Compared to non-Somali patients, Somali patients had significantly lower completion rates of colorectal cancer screening (38.46% vs. 73.35), mammography (15.38% vs. 48.52%), and pap smears (48.79% vs. 69.1%).Use of medical interpreters and primary care services were generally associated with higher preventive services use. |

| Morrison et al., 2013 | US Urban Secondary analysis in a primary care practice database |

Total N= 310 AI = 310 (100%) (Somalia) Gender: women Age:18–65 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in the US: not reported |

Quantitative (medical records) |

Cervical | Disease Free | Screening rates and factors associated with screening |

51% adhered to cervical cancer screening guidelines. Adherence was associated with greater visits to the health care system. The majority of patients (65.8%) saw male providers. However, screening was more likely to occur during a visit with a female doctor (6.9%) compared to a male doctor (1.2%). |

| Ndukwe et al., 2013 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 38 AI = 38 (100%) (Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, Zambia, Ivory Coast) Gender: women Age:20–70 Education: 13.2% ≤ High school Insurance: 16% uninsured Years in the US: not reported |

Qualitative (focus groups/intervi ews) |

Multiple (breast and cervical ) |

Disease Free + Survivors |

Knowledge and awareness of breast and cervical cancer screening |

Cancer awareness was low, especially cervical cancer. Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening included pragmatic and access barriers as well as fatalism, stigma, privacy concerns, and fear. Motivators for screening were reminders from primary care providers, cancer death in the family, and experiencing cancer symptoms. |

| Odedina et al 2009 | US and Nigeria Urban and Rural Community outreach |

Total N= 249 AI = 121 (48.6%) (Nigeria) Gender: men Age: 35–79 Education: 19.5% < High school Insurance: not reported Years in US : M=16.9 SD=9.19 |

Quantitative (cross- sectional survey) |

Prostate | Disease Free | Cognitive- behavioral factors associated to screening |

Immigrant Nigerian men had higher knowledge, more positive attitudes, and higher screening intentions. The role of acculturation was highlighted. |

| Piwowarczyk et al 2013 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 120 AI = 120 (100%) (Congo, Somalia) Gender: women Age: 25–60 Education: 33% < High school Insurance: not reported Years in US: M=7.16 SD=4.12 |

Quantitative (Single arm intervention) |

Multiple (breast and cervical) |

Disease Free | Intervention outcomes (knowledge and intentions) related to screening |

The tailored DVD-based intervention increased knowledge of purposes of mammograms, pap smears, and mental health services, as well as the intent to pursue them. |

| Perkins et al., 2010 | US Urban Community Outreach |

Total N= 73 AI = 3 (4%) Gender: women and men Age: 31–60 Education: M= 13 years Insurance: 5% uninsured Years in the US: M=16 range=4– 33 |

Qualitative (interviews) |

Cervical | Disease Free | Attitudes toward mandatory HPV vaccination |

Most parents accept HPV vaccination for their Daughters. Caucasian parents mostly opposed school entry requirements, citing parental autonomy and fears of promoting promiscuity. Most minority parents would support the school mandate to protect their own daughters and other young women. |

| Samuel et al., 2009 | US Urban Chart review primary care setting |

Total N= 100 AI = 39 (39%) Gender: women Age: 50–75 M=60 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in US: M=5.5 (1–32) |

Quantitative (chart review + survey) |

Multiple (breast, cervical, and colorectal) |

Disease Free | Screening rates and factors associated with screening |

Somali immigrants had the lowest breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening rates compared to Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants. Uptake of colorectal cancer screening was associated with years of residency in the US. Discomfort with exams conducted by male physicians was reported as one of the most salient barriers for screening. |

| Sheppard et al., 2010 | US Urban Community outreach |

Total N= 20 AI = 20 (100%) (West, South, and East Africa) Gender: Women Age:21–60 Insurance: 25% uninsured Education: not reported Years in the US: 3–20 years |

Qualitative (focus group) |

Breast | Disease Free + Survivors |

Knowledge, experiences and beliefs about breast cancer and barriers to screening |

Breast cancer prevention knowledge and screening was low. Breast cancer was commonly conceived as a boil or God’s punishment. Barriers to screening included limited knowledge, lack of insurance, and stigma and secrecy. |

| Sussner et al., 2009 | US Urban Retrospectiv e study and community outreach |

Total N= 146 AI = 11 (11%)* Gender: women Age: M= 45.8, SD=9.6 Education: not reported Insurance: not reported Years in US: M=0.4, SD=0.3 (proportion of years lived in US) |

Quantitative (cross- sectional survey) |

Breast | Disease Free + Survivors |

Perceived barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer |

Being foreign-born was a significant predictor of anticipated negative emotional reactions to genetic testing. Breast cancer specific distress, in particular avoidance symptoms subscale, was positively correlated with three types of barriers to genetic testing: anticipated negative emotions, confidentiality concerns, and family-related guilt. |

| Tsui et al., 2007 | US NHIS sample |

Total N= 70,775 AI = 178 (0.3%) Gender: women Age:18->70 Education: 3% < High school Insurance: 14.9% uninsured Years in US: 70% ≥ 25% proportion of time in the US |

Quantitative (cross- sectional survey) |

Cervical | Disease Free | Screening rates and factors associated with screening |

Birthplace and length of residence in the US were significant predictors of screening rates. The percentage for never having a pap smear test was 19% for recent immigrants compared to 10% among established immigrants and 6% among US born women. Women from Asia, South East Asia, and India had the highest percentage of having never been screened. |

Note: AI: African-born immigrants

• Papers that specify the percentage of Caribbean and categorize the rest as non-Caribbean

Breast Cancer

Ten studies, all conducted in the US, examined breast cancer, either exclusively24,33,34 or along with other types of cancers.32,35 Six were quantitative23,24,32,34,36,37 and four used qualitative methods.33,35,38,39 Paper foci included breast cancer prevention34 and detection, including barriers to genetic testing 24 and barriers to mammography screening.23,32,37,38,33,35

With regard to prevention, Borrell and colleagues34 found that foreign-born Black women were twice as likely to have breastfed their children (a protective factor) compared to US-born Blacks. However, only 3% of the sample was Africa-born and no specific findings were reported for African immigrants. In relation to quantitative studies focused on detection, Sussner and colleagues24 found that foreign-born women of African descent anticipated having greater negative emotional reactions to genetic testing than US born women from African descent. Nevertheless, African immigrant women were underrepresented (89% were Caribbean), and no specific results for the African born population were described. Other studies reported lower mammography screening rates among Somali women in the US compared to non-Somali patients23 and compared to non-African immigrants from Vietnam and Cambodia.36 However, in a study comparing African immigrants from different nationalities,37 Somali women had 5 times higher odds of having received a mammogram compared to the “other African immigrant groups.” Factors associated with higher screening rates among Somalis in these studies included greater interaction with the medical system, use of trained medical interpreters,23 acculturation, and socio-demographic factors, such as education and employment status.37

Several qualitative studies explored African immigrant women’s perceptions of breast cancer and barriers and facilitators to breast cancer screening. Findings from these studies suggest that African immigrants have limited knowledge about cancer,38 associate breast cancer with fear and certain death,33 and sometimes attribute breast cancer to a punishment from God, a curse, or a boil.33,35 A study by Carroll and colleagues (2007)38 conducted with Somalis from different ethnic groups (Bantu and non-Bantu) and different settlement patterns showed how knowledge and perceptions varied depending on the specific ethnic group and acculturation. Bantu Somali immigrants who lived longer in refugee camps and had arrived more recently to the US lacked terms in their native languages to express cancer and were less familiar with screening practices and the notion of preventive health than their non-Bantu Somali counterparts.

Barriers to screening noted in qualitative studies included limited knowledge and awareness about screening practices,32,33,35,38 emotions (e.g. shame, modesty, fear of screening procedures),33,35,38 access and pragmatic barriers (e.g. lack of insurance, financial barriers, transportation, language difficulties),33,35,38 sociodemographic factors (e.g. age, education),35 and cultural values perceived to be at odds with medical practices. For instance, breast self-examination or mammograms challenged Muslim women’s notions of modesty33 and spousal consent for screening was often necessary.35 Motivators for screening included reminders from primary care providers, death of a family member due to cancer, and experiencing cancer symptoms such as breast lump35. Religiosity and spirituality were mentioned as coping strategies.33,35,38 Finally, the only intervention study retrieved was a single-arm intervention consisting of a linguistically and culturally tailored DVD-centered workshop (n= 120) that showed promise in increasing awareness and intentions toward mammograms in African immigrants and refugees from Congo and Somalia.32

Cervical Cancer

Ten out of 11 identified studies focused on cervical cancer detection (pap smear screening) and most were quantitative studies based on cross-sectional surveys or medical record abstractions23,26,32,36,37,40 and included other types of cancer in addition to cervical cancer.23,26,32,36,37,40 There were four qualitative studies35,38,41,42 and one intervention study.32 Only one study was conducted in the UK.41

A US nationally representative sample that included foreign women,26 found disparities in pap screening based on place of birth and length of stay in the US, as a higher percentage of recent immigrants (19%) had never received a pap smear test compared to established immigrants (10 %) and to US born women (6%). Because African immigrants only constituted 2% of the sample, no specific results were discussed.

Harcourt and colleagues37 found that only 52% of a sample of African immigrant women in the US adhered to cervical cancer screening. Contrary to breast cancer screening, where Somali women were more likely to get tested, women from Somalia were less likely to get tested for cervical cancer than their “other African immigrants” counterparts. Similarly, other studies found that Somali women had lower pap smears screening rates compared to non-Somali patients (48.79% vs. 69.1%),23 and to Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrants (around 70% vs. slightly over 70%, and slightly over 80% respectively).36 Factors associated with greater odds of cervical cancer screening included length of residence in the US,26,37 greater interaction with the health care system, and gender concordance of the visits.23 The only intervention study, A DVD-based program by Piwowarczyk and colleagues (2013),34 showed increased awareness and intention toward pap smears in African immigrants.

Qualitative studies shed light upon women’s perceptions of pap-smear tests, important barriers preventing adherence of recommended guidelines, and attitudes toward the HPV vaccine. Women from Somalia and other African nationalities reported a limited knowledge and familiarity with cervical cancer and screening,35,38,41 and they commonly attributed cervical cancer to the will of God or a curse.35,41 Somali Bantu women tended to associate pap smears with detection of infections and routine care for pregnant women rather than screening for cervical cancer.35,38 Other barriers to screening included language difficulties, distrust of the interpreters, fear of the test (pain, lack of trust in sterilization), negative past experiences, and pragmatic (schedule of appointments, childcare) and cultural barriers.35,41 For instance, as many women were circumcised, they anticipated feeling embarrassed by the possible reaction of practitioners unfamiliar with that practice. Muslim women were also wary of having a male doctor perform the test.41 The only study on the HPV vaccine (< 5% African immigrants) showed that minority parents were more supportive of school entry requirements than Caucasian parents, citing the importance of protecting their adolescent daughters as well as other young women.42

Prostate Cancer

Four papers focused on prostate cancer. Most of them had a cross-sectional quantitative design and focused only on prostate cancer.31,43,44 One focused on prevention44 and two on detection (screening),43 including a cross sectional survey of cognitive behavioral factors related to screening43 and a randomized controlled trial screening decision-making intervention.31 The only qualitative study retrieved39 was conducted in the UK and only had one African immigrant prostate cancer survivor in the sample, so no specific findings about African immigrants were presented.

Odedina and colleagues43 compared cognitive behavioral factors (e.g. attitudes, behavioral intentions) related to prostate screening in Nigerian immigrants living in the US with indigenous non-immigrant Nigerians. Results suggested that Nigerian men who migrated to the US had significantly higher knowledge, perceived behavioral control, more positive attitudes, and higher intentions to get screened compared to indigenous Nigerian men. CaP screening was low among Nigerian immigrants (61% overall, 44% within 1 year) but practically non-existent among the indigenous Nigerian men (7.2% overall, 5.6% within 1 year). Using the same study sample, Kumar and colleagues44 found that Nigerian immigrants in the US practiced healthier lifestyle choices, such as significantly higher fruit and whole grain intake, more hours of purposeful physical activity, and lower tobacco use and intake of trans fats compared to Nigerians who had not migrated.

Lepore and colleagues31 conducted a randomized controlled trial within a sample of predominantly immigrant black men (n= 490) (77% Caribbean) in the US to evaluate the efficacy of a decision support intervention focused on prostate cancer testing. The intervention aimed to provide information, exercises (e.g., values clarification), and encouragement to aid informed testing decisions that were consistent with the men’s own values. The intervention improved prostate cancer testing knowledge, decision conflict, and doctor-patient communication among black men without arousing anxiety or biasing men for or against testing. However, the intervention had no effect on PSA testing.

Uterine Cancer

The only retrieved uterine cancer study13 compared survival rates in a sample of 311 black women from different countries of origin using cancer registry data in the US. US born women had a slightly higher but not significant five-year survival rate compared to their foreign born counterparts (56.7% vs. 49.7%). Nevertheless, most foreign born women were Caribbean (1% African immigrants), so no specific information was displayed.

Colorectal Cancer Screening

Two quantitative studies conducted in the US focused on detection, as they examined colorectal cancer screening rates among Somali immigrants. Morrison and colleagues40 found that Somali patients had lower rates of colorectal cancer screening compared to non-Somali patients (38.46% vs. 73.35%). Higher screening was correlated with higher use of primary care services. Comparing screening rates within immigrant groups, Samuel and colleagues36 found that Somali women had the lowest colorectal (8%) screening rates. Length of stay in the US was related with a 39% increase in undergoing a colonoscopy. An additional survey administered to 15 women (2 Somali) women identified discomfort with a male provider as one of the main screening barriers.

Unspecified Cancer

One qualitative study conducted five focus groups in the UK with immigrants from Nigeria and Ghana stratified by gender, nationality, and religion (Christians and Muslims) to examine cancer perceptions.45,46 Study results suggested that participants had limited knowledge about cancer causes and symptoms and some lacked an equivalent translation in their own languages. Denial, apprehension, fear of a cancer diagnosis, shame, and stigma were mentioned as barriers to seeking medical services and communicating with family members.45,46 Change in the environment and lifestyle in the UK (e.g. nuclear energy, fatty food) were mentioned as factors that increased their cancer risk. Most participants believed in both turning to God for healing and seeking healthcare when one had cancer 46 and expressed mixed opinions about the effectiveness of traditional African herbal medicine to cure cancer.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of cancer control research in this growing subgroup. Findings from this systematic literature review highlight that (1) African immigrants are underrepresented and/or grouped with other populations, limiting our understanding of how results are most relevant to African immigrants; (2) most studies focus on the detection phase of the cancer control continuum (screening) in disease-free populations and suggest suboptimal cancer screening rates in several subpopulations of African immigrants. Higher screening appears to be related to health care factors (provider recommendation) and acculturation (e.g. number of years in the US) while access factors (limited insurance), pragmatic factors (transportation), and psychosocial factors (limited knowledge, fear, stigma, shame, cultural values) were perceived as main barriers; (3) there are limited cancer related interventions specifically designed for African immigrants. These findings highlight research gaps and can inform potential future lines of research and suggest health care related recommendations (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Research and Health Care Related Recommendations

| Research Related Recommendations |

|---|

|

| Healthcare Related Recommendations |

|

There has been a paucity of research with African-born immigrants as more studies focus on Caribbean populations.24,31,39,47,48 While a few studies were conducted in large samples, immigrants constituted less than 5% of the sample. 13,31,39,48 In addition to limited representation in studies, some research often failed to account for the specificities within African-born immigrants and either lump them with other groups (e.g. Caribbean, Latin American), or categorize them as “Black, ” “other Africans,” or “non-Caribbean” without specifying participants’ nationalities.24,26,31,42,47,48 Carefully, examining differences by subgroups is important because the studies that differentiate African born immigrants from other subpopulations suggest that there are important differences in cancer risks, cancer screening, and cancer perceptions and experiences between African born immigrants and US born populations,23,26,40,47 US born Black, 24,48 and with immigrants from other non-African countries.36 Moreover, differences were reported between African immigrants from different nationalities,37 between Africans who migrated and who did not migrate,43,49 and even between different ethnic groups within the same African country.38 Thus, these studies point to the need for more research that examines nuances among specific subpopulations.

Additionally, there is limited diversity within the African immigrant samples, as most studies tend to include immigrants who are mostly from Somalia and Nigeria, mostly insured,23,24,31,33,36,37,47 living in urban settings,24,33,35–37,47,48 English speakers,24,26,35,45,46 and non- recently arrived immigrants.26,33,37,39,43,50 Thus, uninsured, recently arrived, non-English speakers are underrepresented in research, which suggests a challenge in reaching this population. Conducting community-based participatory research with community based organizations like the African Women’s Cancer Awareness Association that serve this type of population (e.g. uninsured, non-English speaker, diverse African nationalities) may be a potential strategy to access this underrepresented group.

Most studies have been conducted in disease free populations and focused mainly on the cancer detection phase of the cancer control continuum (cancer screening). Study results suggested that cancer screening rates are suboptimal23,26,36,37,40 and studies that compare African immigrants with other populations show screening disparities.23,26,36 Barriers to cancer screening included access factors (e.g. health insurance, financial barriers)26,33,35,37,41 and pragmatic constraints (e.g. language difficulties, childcare).35,41 Other psychosocial barriers noted were limited knowledge and awareness, beliefs (e.g. linking cancer with God’s punishment or a death sentence), stigma and secrecy surrounding cancer, and anticipated emotions to the test or diagnosis such as shame, embarrassment, or fear.24,35,41,45,46 Perceiving cultural values to be at odds with medical system posed challenges to cancer screening as well.33,36,41

While some access, pragmatic, and psychosocial barriers have been noted in African Americans and other immigrant populations,14–16 other barriers do not necessarily overlap with the subgroups that African immigrants tend to be lumped with. For instance, language difficulties, including the lack of an equivalent translation to cancer33,35,41 do not constitute a barrier for African Americans or Caribbean. Medical mistrust, which has been identified as a barrier for using cancer services in African Americans and Caribbean51–53 did not emerge as an obstacle for African immigrants. In fact, several studies noted that African immigrants had a positive perception of health services and providers.37–39 Although screening fear and embarrassment have been reported in African American and Caribbean samples,54–56 to our knowledge, embarrassment related to female circumcision 41 has not been reported as a barrier to cervical screening in Caribbean or African American populations. Shame and secrecy related to a cancer diagnosis and the attribution of cancer to a curse or God’s punishment was also salient among African immigrants.33,35 Thus, lumping together African immigrants with other subpopulations may result in overlooking important differences that can inform prevention efforts in specific groups. For instance, it would be important for health care providers working with African immigrants to be aware of the cultural practices (e.g. female circumcision), preferences (e.g. provider-patient gender concordance), and specific barriers African immigrants face for cancer screening in order to provide linguistically and culturally sensitive services. Such services could include incorporating patient navigators to address access and pragmatic barriers, providing written and oral information in their native languages, engaging spiritual leaders as health advocates, and conducting outreach efforts in community settings to increase cancer knowledge and services awareness.33

In relation to acculturation, some studies support previous findings with other non-African immigrants21 that point to the role of acculturation in increasing screening rates. In this review, several factors used as proxies for acculturation such as the length of stay in the US,26,36–38 English preference,38 and higher interaction with the medical system23 were related to higher screening rates in African immigrants. Despite the beneficial impact of acculturation in screening rates, participants in qualitative studies identified acculturation with environmental and life style changes such as exposure to nuclear energy, the lack of physical exercise, and fatty diet, that could increase their cancer risks.38,46 Interestingly, Kumar and colleagues49 study suggested that Nigerians who migrated to the US had a healthier life style (diet and physical exercise) compared to their Nigerians counterparts who did not migrate to the US. Thus, further research is needed to elucidate the impact of acculturation in different cancer preventive behaviors among African immigrants.

Within the 20 articles revised, there were only two intervention studies. One was a RCT but the sample mainly consisted of Caribbean immigrants.31 The single arm intervention with women from Somalia and Congo study showed promising results of a culturally sensitive DVD workshop around breast and cervical cancer screening.32 Thus, developing and testing other culturally targeted interventions for African immigrants across different types of cancers and across the cancer continuum is warranted. Potential intervention targets include increasing cancer knowledge, services awareness, targeting shame and stigma in the community, screening and treatment decision aids, interventions designed to improve doctor-patient communication, and survivorship issues.

The study had certain limitations. Due to publication bias and to the limitations of using MeSH terms, we cannot guarantee that all studies using African-born samples were included in this review. MeSH terms uses automatic mapping, which means that search terms may be translated to the closest MeSH term, which carries the risk of losing accuracy. However, we used five different search engines and we chose broad MeSH terms and eligibility criteria to capture as many studies as possible. We also used the paper’s reference lists and other scholar’s suggestions to complement the search. The fact that we did not set a specific percent of African-born immigrants in the studies study samples as eligibility criteria resulted in the retrieval of studies that included very low percentages of African immigrants. Thus, the study results may not be representative of the African-born population. Despites these caveats, this is the first review that addresses cancer related issues in African immigrant populations. The review suggests the need to advance the research in this underrepresented population and the need to avoid lumping African immigrants with other groups or under broad categories “African.” Conducting more studies with immigrants from diverse African nationalities, reaching out to the uninsured, newly arrived, non-English speaking population, and developing and testing interventions for disease free as well as cancer survivors is warranted.

Highlights.

African immigrants are underrepresented in cancer research

Most research lumps African immigrants with other subpopulations

There are limited intervention studies and survivor’s studies

Studies suggest suboptimal screening rates and screening disparities

Development and testing of interventions and research with survivors is needed

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (Sheppard: PI, Grant Award # 2012-5) and partly by a Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation Baccalaureate Training in Breast Cancer Health Award to Ocla Kigen (PI. Dr. Lucile Adams-Campbell, Award#: PBTDR12228366)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau. [Accessed 4-15-2013, 2013]; http://www.census.gov/2010census/. Updated 2010.

- 2.Immigration Policy Center. [Accessed 04/02, 2014];African immigrants in America: A demographic overview. http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/just-facts/african-immigrants-america-demographic-overview. Updated 2012.

- 3.Venters H, Gany F. African immigrant health. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(2):333–344. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X. Cancer information disparities between U.S.- and foreign-born populations. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(Suppl 3):5–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazargan M, Bazargan SH, Farooq M, Baker RS. Correlates of cervical cancer screening among underserved Hispanic and African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;39(3):465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lofters AK, Hwang SW, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: A population-based cohort study. Prev Med. 2010;51(6):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: Results from the 2000 national health interview survey. Cancer. 2003;97(6):1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shih YC, Elting LS, Levin B. Disparities in colorectal screening between US-born and foreign-born populations: Evidence from the 2000 national health interview survey. Journal of Cancer Education. 2008;23(1):18–25. doi: 10.1080/08858190701634623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goel MS, Wee CC, McCathy EP, Davis RB, Ngo-Metger Q, Phillips RS. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: The importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Consedine NS. Are we worrying about the right men and are the right men feeling worried? conscious but not unconscious prostate anxiety predicts screening among men from three ethnic groups. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(1):37–50. doi: 10.1177/1557988311415513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouri EM, He Y, Winer EP, Keating NL. Influence of birthplace on breast cancer diagnosis and treatment for Hispanic women. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment. 2010;121(3):743–751. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen SS, He Y, Ayanian JZ, et al. Quality of cancer care among foreign-born and US-born patients with lung or colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(23):5497–5506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creque A, Taioli E, Attong-Rogers A, Ragin C. Disparities in uterine cancer survival in a Brooklyn cohort of Black women. Future Oncol. 2010;6(2):319–327. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De AI, Hubbell FA, McMullin JM, Sweningson JM, Saitz R. Impact of U.S. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1525-1497; 0884-8734;3):290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Echeverria SE, Carrasquillo O. The roles of citizenship status, acculturation, and health insurance in breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrant women. Med Care. 2006;44(8):788–792. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215863.24214.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahidi NC, Homayoon B, Cheung WY. Factors associated with suboptimal colorectal cancer screening in US immigrants. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;36(4):381–387. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318248da66. Accessed 20130722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson CE, Mues KE, Mayne SL, Kiblawi AN. Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A systematic review using the health belief model. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008;12(3):232–241. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31815d8d88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consedine NS, Horton D, Ungar T, Joe AK, Ramirez P, Borrell L. Fear, knowledge, and efficacy beliefs differentially predict the frequency of digital rectal examination versus prostate specific antigen screening in ethnically diverse samples of older men. Am J Mens Health. 2007;1(1):29–43. doi: 10.1177/1557988306293495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consedine NS, Ladwig I, Reddig MK, Broadbent EA. The many faces of colorectal cancer screening embarrassment: Preliminary psychometric development and links to screening outcome. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):559–579. doi: 10.1348/135910710X530942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Nguyen TT, et al. Pap smear receipt among Vietnamese immigrants: The importance of health care factors. Ethn Health. 2009;14(6):575–589. doi: 10.1080/13557850903111589. Accessed 20091202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jandorf L, Ellison J, Villagra C, et al. Understanding the barriers and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening among low income immigrant Hispanics. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2010;12(4):462–469. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9274-3. Accessed 20100715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown WM, Consedine NS, Magai C. Time spent in the United States and breast cancer screening behaviors among ethnically diverse immigrant women: Evidence for acculturation? J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(4):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison TB, Wieland ML, Cha SS, Rahman AS, Chaudhry R. Disparities in preventive health services among Somali immigrants and refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):968–974. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sussner KM, Thompson HS, Jandorf L, et al. The influence of acculturation and breast cancer-specific distress on perceived barriers to genetic testing for breast cancer among women of African descent. Psychooncology. 2009;18(9):945–955. doi: 10.1002/pon.1492. Accessed 20090831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeff LC, McKenna MT. Cervical cancer mortality among foreign-born women living in the United States, 1985 to 1996. Cancer Detection & Prevention. 2003;27:203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsui J, Saraiya M, Thompson T, Dey A, Richardson L. Cervical cancer screening among foreign-born women by birthplace and duration in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(10):1447–1457. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel MS, Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: The importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X. Cancer information disparities between U.S.- and foreign-born populations. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 3):5–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lepore S, Wolf RL, Basche CE, et al. Informed decision making about prostate cancer testing in predominantly immigrant black men: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44:320–330. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piwowarczyk L, Bishop H, Saia K, et al. Pilot evaluation of a health promotion program for African immigrant and refugee women: The UJAMBO program. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(1):219–223. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheppard VB, Juleen C, Nwabukwu I. Breaking the silence barrier: Opportunities to address breast cancer in African-born women. National Medical Association. 2010;102:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borrell LN, Castor D, Conway FP, Terry MB. Influence of nativity status on breast cancer risk among US black women. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ndukwe EG, Williams KP, Sheppard V. Knowledge and perspectives of breast and cervical cancer screening among female African immigrants in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. J Cancer Educ. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0521-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samuel PS, Pringle JP, James NW, 4th, Fielding SJ, Fairfield KM. Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening rates amongst female Cambodian, Somali, and Vietnamese immigrants in the USA. Int J Equity Health. 2009;8 doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-30. 30-9276-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harcourt N, Ghebre RG, Whembolua G, Zhang Y, Osman SW, Okuyemi KS. Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening behavior among African immigrant women in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, Volpe E, Diaz K, Omar S. Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and preventive health care among Somali women in the united states. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(4):360–380. doi: 10.1080/07399330601179935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bache RA, Bhui KS, Dein S, Korszun A. African and black Caribbean origin cancer survivors: A qualitative study of the narratives of causes, coping and care experiences. Ethn Health. 2012;17:187–201. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.635785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrison TB, Flynn PM, Weaver AL, Wieland ML. Cervical cancer screening adherence among Somali immigrants and refugees to the united states. Health Care Women Int. 2013 doi: 10.1080/07399332.2013.770002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdullahi A, Copping J, Kessel A, Luck M, Bonell C. Cervical screening: Perceptions and barriers to uptake among Somali women in Camden. Public Health. 2009;123:680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkins RB, Pierre-Joseph N, Marquez C, Iloka S, Clark JA. Parents’ opinions of mandatory human papillomavirus vaccination: Does ethnicity matter? Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20(6):420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Odedina FT, Yu D, Akinremi TO, Reams RR, Freedman ML, Kumar N. Prostate cancer cognitive-behavioral factors in a west African population. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11:258–267. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar NB, Yu D, Akinremi TO, Odedina FT. Comparing dietary and other lifestyle factors among immigrant Nigerian men living in the US and indigenous men from Nigeria: Potential implications for prostate cancer risk reduction. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(5):391–399. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehiwe E, McGee P, Filby M, Thompson K. Black African migrants’ perceptions of cancer: Are they different from those of other ethnicities, cultures and races? Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care. 2012;5:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehiwe E, McGee P, Thomson K, Filby M. How black West African migrants perceive cancer. Diversity and Equality in Health and Care. 2013;10:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creque A, Taioli E, Attong-Rogers A, Ragin C. Disparities in uterine cancer survival in a Brooklyn cohort of black women. Future Oncol. 2010;6(2):319–327. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borrell LN, Castor D, Conway FP, Terry MB. Influence of nativity status women. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1099–3460; 2):211–220. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar NB, Yu D, Akinremi TO, Odedina FT. Comparing dietary and other lifestyle factors among immigrant Nigerian men living in the US and indigenous men from Nigeria: Potential implications for prostate cancer risk reduction. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(5):391–399. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar NB, Yu D, Akinremi TO, Odedina FT. Comparing dietary and other lifestyle factors among immigrant Nigerian men living in the US and indigenous men from Nigeria: Potential implications for prostate cancer risk reduction. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(5):391–399. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halbert CH, Weathers B, Delmoor E, et al. Racial differences in medical mistrust among men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2553–2561. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pedersen VH, Armes J, Ream E. Perceptions of prostate cancer in black African and black Caribbean men: A systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2012;21(5):457–468. doi: 10.1002/pon.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ng P, Schoenfeld ER, Hennis A, Wu SY, Leske MC, Nemesure B. Factors influencing prostate cancer healthcare practices in Barbados, west indies. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(3):653–660. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9654-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Consedine NS, Morgenstern AH, Kudadjie-Gyamfi E, Magai C, Neugut AI. Prostate cancer screening behavior in men from seven ethnic groups: The fear factor. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):228–237. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Consedine NS, Horton D, Ungar T, Joe AK, Ramirez P, Borrell L. Fear, knowledge, and efficacy beliefs differentially predict the frequency of digital rectal examination versus prostate specific antigen screening in ethnically diverse samples of older men. Am J Mens Health. 2007;1(1):29–43. doi: 10.1177/1557988306293495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Consedine NS, Ladwig I, Reddig MK, Broadbent EA. The many faces of colorectal cancer screening embarrassment: Preliminary psychometric development and links to screening outcome. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(3):559–579. doi: 10.1348/135910710X530942. Accessed 20110704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]