Summary

Macrophages are versatile cells of the hematopoietic system that display remarkable functional diversity encompassing innate immune responses, tissue development, and tissue homeostasis. Macrophages are present in almost all tissues of the body and display distinct location-specific phenotypes and gene expression profiles. Recent studies also demonstrate distinct origins of tissue-resident macrophages. This emerging picture of ontological, functional, and phenotypic heterogeneity within tissue macrophages has altered our understanding of these cells, which play important roles in many human diseases. In this review, we discuss the different origins of tissue macrophages, the transcription factors regulating their development, and the mechanisms underlying their homeostasis at steady state.

Keywords: monocytes/macrophages, cell differentiation, immune system ontogeny, lineage commitment

Introduction

Macrophages were identified by Ilya Metchnikoff in the late 19th century by virtue of their phagocytic activity (1). Subsequent development of antibodies against macrophage-specific surface markers such as F4/80 and CD68 led to an appreciation of their widespread distribution in almost all tissues in the body (2–5). Further examination of their morphology, expression patterns of surface markers, and gene expression profile revealed significant differences between macrophages at different locations (6, 7). Such phenotypic differences were also accompanied by distinct functions (Table 1). Originally described as critical cells of the innate immune system, we now recognize their important roles in the development and homeostasis of the tissues in which they reside (6, 8). Recent studies are beginning to uncover the transcriptional regulation of such tissue-specific macrophages (9–12). Macrophage heterogeneity has also raised questions regarding their origin. A long-held dogma in the field has been that all tissue-resident macrophages are derived from local differentiation of circulating monocytes (13). However, recent studies have provided conclusive evidence for the existence of monocyte-independent tissue-resident macrophages, leading to a paradigm shift in this model (14, 15). In this review, we discuss recent conceptual advances in the origin, development, and homeostasis of the diverse tissue-resident macrophages.

Table 1. Tissue-resident macrophages at selected location in mice.

Comments on origins and underlying developmental mechanisms are included for instance where supporting experimental evidence exists in the literature.

| Tissue | Macrophage | Phenotype and function | Origin and development at steady state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Red Pulp Macrophages | F4/80+VCAM+. Phagocytosis of old and damaged erythrocytes, heme degradaion, and iron recycling. | Mixed but predominantly YS-derived. Depends on transcription factor Spic that is induced by heme. |

| Marginal zone macrophages | MACRO+SIGN-R1+. Immune surveillance and retention of marginal zone B cells. | Monocyte-derived. Depends on transcription factor LXRα | |

| Margional zone metallophilic macrophage | CD68+CD169+. Immune surveillance. | Monocyte-derived. Depends on transcription factor LXRα | |

| Tingible body macrophages | CD68+MERTK+MFG-E8+Tim4+. Clearence of apoptotic B cells | ||

| Lung | Alveolar macrophages | CD68+F4/80+CD11C+SiglecF+MARCO+. Immune surveillance and surfactant homeostasis. | Fetal monocyte-derived. Maintained by local proliferation. Depends on GM-CSF signalling and Bach2 transcription factor for normal function. |

| Interstitial macrophages | CD68+F4/80+CD11C−. Modulates DC function to prevent allegic reactions to airborne antigens. | Mixed. | |

| Peritoneal cavity | Large peritoneal macrophages | F4/80hi CD11b+MHC-II−. Immune surveillance and clearance of apoptotic cells | Depends on the transcription factor GATA6 for development. Retinoic acid signaling is also important for its development. |

| Small peritoneal macrophages | F4/80+ CD11b+MHC-II+. Immune surveillance | Monocyte-derived. | |

| Pleural cavity | Pleural macrophages | F4/80+. Immune surveillance | Can proliferate during TH2 inflammation and in the presence of IL-4. |

| CNS | Microglia | F4/80+CD11b+Iba1+CD45lo. Promotes normal neuronal development and function. Synaptic remodelling. Immune surveillance. | YS-derived. Maintained by local proliferation. Dependence on IL-34. |

| Perivascular macrophages | F4/80+CD11b+Iba1+CD163+. Immune surveillance. | Monocyte-derived. | |

| Meningeal macrophages | F4/80+CD11b+Iba1+CD45hi. Immune surveillance. | Monocyte-derived. | |

| Choroid plexus macropahges | F4/80+CD11b+Iba1+CD45hi. Immune surveillance. | Monocyte-derived. | |

| Liver | Kupffer cells | F4/80hiCD11bloCD169+CD68+CD80lo. Clearance of blood-borne particles and microorganisms. | Mostly YS-derived |

| Other liver macrophages | F4/80+CD11b+CD80hi. Immune surveillance. | Monocyte-derived | |

| Skin | Dermal macrophages | F4/80+CD11b+CD169hiCD64hiMERTK+. Immune surveillance. | Mixed but a major fraction is monocyte-derived. |

| Langerhans cells | F4/80+CD11b+CD11C+Langerin+. Immune surveillance. | Most derived from fetal monocytes and maintained by local proliferation. Dependent on IL-34. | |

| Bone | Bone marrow macrophages | F4/80+VCAM1+CD169+. Support erythropoiesis. | Depends on the transcription factor Spic for development. |

| Osteoclast | RANK+. Multinucleated. Bone resoption. | Depends on the transcription factors Mitf, C-fos, and NFATc1 for development. Dependence onRANK-RANKL signaling. | |

| Blood | Ly6Clo patrolling monocytes | CD115+CD11bhiCDLy6CloCD43+. Immune surveillance. Maintains vascular integrity. | Derived from Ly6Chi monocytes. Depends on transcription factor Nr4a1 for development. |

| GI tract | Macrophages of the intestinal lamina propria | F4/80+CD11b+CD64+. Immune response to commensals. Maintains instestinal homeostasis. | Monocyte-derived |

Origin of tissue-resident macrophages

Early work in the 1960s by Van Furth and Zanvil Cohn (13, 16) showed in vitro differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and a developmental continuum between circulating monocytes and some tissue macrophages in vivo. These studies concluded that monocytes and macrophages are essentially non-dividing cells and that proliferative capacity was restricted to their bone marrow progenitors (promonocyte) (17, 18). A linear model was proposed where proliferating promonocytes in the bone marrow give rise to circulating monocytes that extravasate into tissues and differentiate into macrophages. Generalization of this model led to the concept of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) in the early 1970s (19). Of note, most studies validating the MPS model were based on inducing inflammation to promote monocyte extravasation or on generating bone marrow chimeras with irradiated recipients. As discussed below, recent studies now demonstrate this model to be an oversimplification at the steady state.

In mammals, there are two major phases of hematopoiesis: primitive and definitive (20). The initial primitive phase is restricted to the generation of erythrocytes and macrophages and occurs in the yolk sac (YS). The ensuing definitive phase is characterized by the appearance of the adult-type hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that generates all major hematopoietic lineages. Definitive hematopoiesis first occurs in the aorta-gonads-mesonephros (AGM) region of the embryo and then sequentially moves to the liver, spleen, and finally bone marrow where it persists in the adult (21). The presence of macrophages in the yolk-sac before the appearance of definitive hematopoiesis and monocytes has been long recognized (22). These primitive macrophages colonize various tissues in the embryo and differ from adult macrophages in proliferative capacity, lack of peroxidase activity, and the absence of a monocyte precursor (23). This distinction is largely conserved across many species, suggesting that embryonic and adult macrophages likely represent distinct lineages (24). This lineage distinction was perceived to reflect distinct functional requirements where embryonic macrophages are important for tissue remodeling and adult macrophages primarily involved in host defense (24). However, it was unclear whether embryonic macrophages persist into adulthood. The pathways regulating embryonic and adult macrophage development were also unknown. Recent use of genetically engineered mice for lineage definition and lineage tracing has begun to answer some of these questions.

Microgliaare macrophages of the central nervous system (CNS) that play important roles in injury, infection, development, and homeostasis (25). Ginhoux and colleagues (26) used a CX3CR1GFP and a tamoxifen inducible Runx1CreER : Rosa26LSL-eYFP reporter mouse to demonstrate the presence of microglia before the onset of definitive hematopoiesis and their persistence in the adult brain. Indeed, the majority of adult microglia was derived from YS (primitive hematopoiesis) with minimal contributions from HSCs (definitive hematopoiesis). These findings were congruent with other studies demonstrating self-renewal of microglia and their independence from monocytes in adult mice (27–29). Therefore, at the steady state microglia represent YS-derived macrophages that do not require a monocyte intermediate, a major break from the MPS model. Subsequently, important insight into tissue-macrophage ontology was provided by Schultz and colleagues where they show co-existence of F4/80hi CD11blo YS-derived and F4/80int CD11bhi HSC-derived macrophages in various tissues, and demonstrated the selective requirement for the gene C-myb in the development of HSC-derived, but not YS-derived, macrophages. The co-existence of such ontologically distinct macrophage subsets within various tissues have since been corroborated by other groups (30, 31).

The proportion of YS- and HSC-derived macrophages in various tissues varies significantly at the steady state with examples at both ends of the spectrum (31–33). While microglia are predominantly YS-derived, macrophages at intestinal lamina propria, marginal zone of the spleen, and uterus require a constant influx of monocytes for their maintenance (10, 34–37). Other locations such as epidermis, splenic red pulp, liver, lung, etc. display a mix of YS and HSC-derived macrophages (31, 32). However, the situation can change dramatically with tissue insults that deplete resident macrophages. In such instances circulating monocytes can be recruited for long-term reconstitution of the 'lost' tissue-macrophages. A common example of this is seen during macrophage reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation. Macrophages at various locations can also be depleted by clodronate via liposomes. Macrophage recovery after such clodronate-liposome based depletion is also largely driven by monocyte recruitment and differentiation (31). There are additional tissue-specific damages that can effectively deplete specific resident macrophages. For example, resident microglia can be depleted by specific a combination of radiation and chemotherapy drugs. When such 'preconditioning' is followed by HSC transplantation, donor monocytes are recruited to the CNS for long-term reconstitution of microglia (28, 38). This is distinct from the short-lived inflammatory macrophages that are generated from monocytes in response to inflammation (39, 40). Alveolar and parenchymal macrophages in the lungs express the surface integrin CD11c and can be depleted by intra-tracheal administration of diphtheria toxin in CD11c-DTR transgenic mice. Upon depletion, monocytes were found to reconstitute these cells over a period of time (41, 42). Similarly, red pulp macrophages (RPMs) in the spleen can be depleted in the presence of excess environmental heme, which leads to local differentiation of monocytes into RPMs, thus 'replenishing' the lost population (43, 44). These examples demonstrate that YS-derived macrophages can be permanently replaced by monocyte-derived macrophages under certain pathological conditions.

Resident macrophages in most tissue do not require an ongoing input from circulating monocytes and can be maintained by self-renewal (45–47). However, lineage tracing experiments show that not all of these resident macrophages are derived from YS progenitors either (31, 32). This seemingly paradoxical observation is explained by studies demonstrating (discussed below) that fetal monocytes seed various tissues during embryogenesis to give rise to long-lived tissue-resident macrophages. Therefore, although monocyte-derived, these macrophages are not dependent on adult monocytes for their maintenance at the steady state. Langerhans cells (LCs) in the skin display dual characteristics of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages and are maintained largely by self-renewal in the adults (48). Using a tamoxifen-inducible CreER-based fate mapping, Hoeffel and colleagues (49) showed that early embryonic LC-like cells are predominantly derived from YS, of which only a small fraction persist into adulthood. In a second wave, fetal liver-derived monocytes populate the skin in later stages of embryogenesis to generate LC-like cells, which persist into adulthood (49). Alveolar macrophages in the lungs play important roles in lung development, surfactant homeostasis, and pathogen clearance (50). In a recent study, Guilliams and colleagues reported that while YS-derived macrophages were present at early stages of lung development, mature alveolar macrophages make their appearance much later and complete their development during the first week after birth. Importantly, these mature AMFs were found to be predominantly derived from fetal monocytes (51). These studies suggest that while YS-derived macrophages dominate in the early stages of embryogenesis, they are likely overtaken by HSC-derived macrophages as the embryo develops (26, 51, 52).

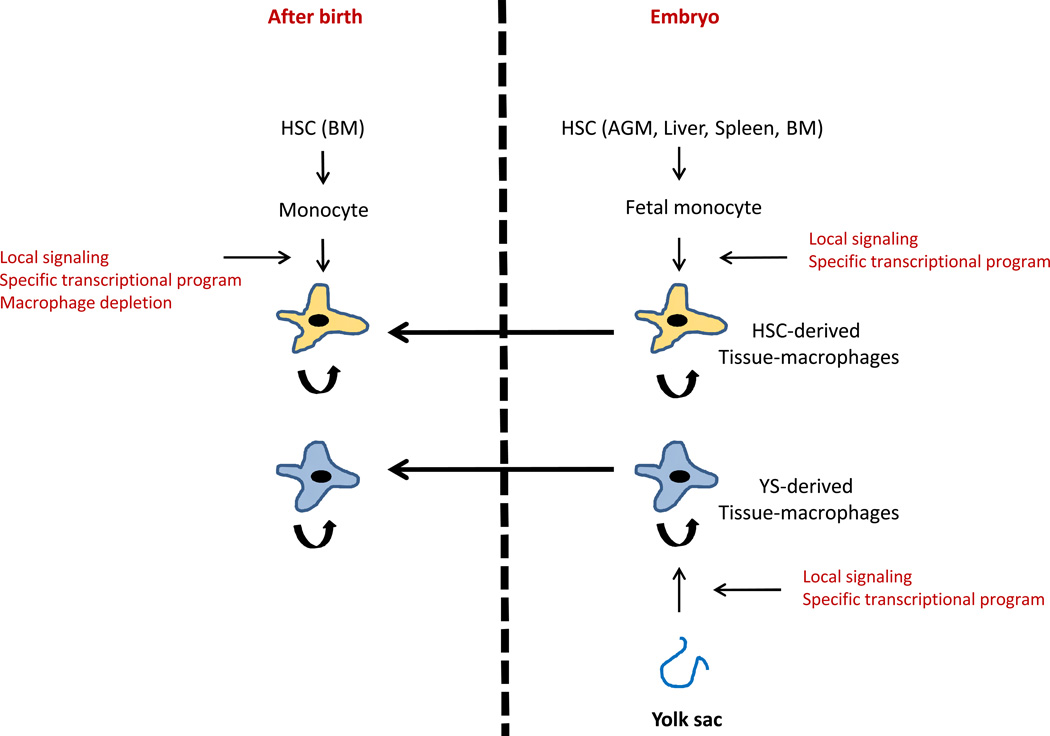

Tissue-resident macrophages may therefore have multiple sources: YS-progenitors, fetal monocytes, or adult monocytes (Fig. 1). While YS- and fetal monocyte-derived macrophages seem to dominate in the steady state, adult monocytes are important for reconstituting these cells after depletion in certain pathological conditions. However, the limited role of monocytes in generating tissue-resident macrophages at the steady state does raise questions regarding the function of monocytes under homeostasis. The field recognizes two major subsets of monocytes in mice; Ly6ChiCX3CR1int (classical monocytes) and Ly6CloCX3CR1hi (non-classical monocytes), with additional markers differentially expressed between the two subsets (15, 53, 54). Ly6Chi classical monocytes have a short life and give rise to inflammatory macrophages and DCs in the tissue under inflammatory conditions (55). Their transient nature and robust differentiation under inflammatory conditions were often cited in support of the MPS model. However, we now know that with the exception of some tissue such as the intestinal lamina propria (discussed above), Ly6Chi monocytes do not differentiate into tissue macrophages in the absence of inflammation. Instead, these cells give rise to the Ly6Clo non-classical monocytes in blood at the steady state (30, 56, 57). The Ly6Clo monocytes were initially suggested to be a source of tissue-macrophages (41). However, subsequent studies describe a unique intravascular 'patrolling' behavior and clearance of damaged endothelial cells by these cells for maintaining the vascular integrity (54, 57). Such a role in the maintenance of tissue (blood vessel) homeostasis is reminiscent of macrophage functionality, suggesting that Ly6Clo non-classical monocytes may be considered as resident blood macrophages. Additionally, Jakubzick and colleagues (58) recently demonstrated that circulating monocytes do extravasate into tissue in the absence of inflammation, but undergo minimal differentiation, instead picking up antigens for delivery to draining lymph nodes. Therefore, the emerging picture suggests that monocytes are not just the obligatory precursors of macrophages or DCs but have their own unique functions at the steady state.

Fig. 1. Embryonic and postnatal origins of tissue-resident macrophages.

Macrophages are color coded to indicate origin. Arrows connecting macrophages indicate persistence into postnatal phase.

The new facets of macrophage origins and ontology discussed above raise several important questions. Are YS-derived tissue resident macrophages and their monocyte-derived replacements under pathological conditions functionally equivalent? Macrophages are also increasingly implicated in various diseases including cancer, atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome (59–61). It will be important to know which ontological subsets are preferentially involved in such pathological processes. The ontological distinction between fetal monocyte- and adult monocyte-derived macrophages may also have functional implications. While adult 'monopoiesis' has been well studied (described below), we know very little about fetal monopoiesis. Definitive hematopoiesis in the fetal liver generates monocytes that are released into the circulation beginning around day E12.5 (49). While these fetal monocytes share several markers with adult monocytes including the expression of CD11b, CSF1R, and Ly6C, unlike adult monocytes they are not dependent on CSF1R for their generation (26). Fetal monocytes also possess high proliferative potential unlike adult monocytes (26). At present the extent of similarities and differences between fetal and adult monocytes as well as its implications on the macrophages they generate is unclear.

Development of tissue-resident macrophages

The development of YS-derived macrophages is poorly understood and awaits further work. However, HSC-derived development of adult MPS comprising monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells has been studied in detail (15, 62). Adult hematopoiesis is a highly regulated and well-coordinated process where multipotent HSCs give rise to all mature blood lineages by step-wise loss of alternative lineage potential (21). Accordingly, myeloid development proceeds via sequential generation of the common myeloid progenitor (CMP), the granulocyte/macrophage progenitor (GMP), and the macrophage/DC progenitor (MDP) with increasingly restricted lineage potential (15). DC and monocyte/macrophage lineages diverge from the MDP via generation of the common monocyte/macrophage progenitor (cMoP) and the common DC progenitor (CDP) (63–66). DCs and macrophages also differ in their requirement of cytokines for their development. While the monocyte/macrophage lineage is dependent on M-CSF signaling, the DC lineage requires FLT3 (67–70).

In the hierarchical development of the hematopoietic lineage, loss of alternate lineage potential and stable commitment to downstream lineages is induced and maintained by transcription factor networks. PU.1 (Spi1) and C/EBP-α are transcription factors that promote myeloid lineages, dramatically exhibited by their ability to reprogram lymphoid cells and fibroblasts into myeloid cells (71–73). Indeed, PU.1 deletion disrupts both YS-and HSC- derived macrophage development (32). However, lymphoid lineage is also affected in PU.1 knockout mice including a complete block in B-cell development (74, 75). Different levels of PU.1 in progenitor cells was found to direct macrophage vs. B-cell identity, with a low concentration promoting B-cell development and higher levels blocking B-cell development and inducing macrophage differentiation (76). Similarly, higher levels of PU.1 were found to promote DC over macrophage and macrophage over neutrophil development (77, 78). One basis for this 'graded response' to PU.1 levels is its antagonistic relationship with other transcription factors. C/EBP-α has been shown to promote neutrophil development and antagonize the 'macrophage-promoting' activity of PU.1, such that the ratio of PU.1/ C/EBP-α controls the choice between neutrophil and macrophage fate (78–80). The cytokine G-CSF induces C/EBP-α expression in the progenitors to skew the PU.1/ C/EBP-α ratio in favor of neutrophil development (78). A similar antagonistic relationship between PU.1 and the macrophage-associated transcription factor MafB underlie the differential effects of PU.1 levels in DC vs. macrophage differentiation (77, 81, 82). Indeed, this type of competition with other stage-specific transcription factors allows PU.1 to steer progenitors towards MPS differentiation. Examples include antagonism between PU.1 and GATA1 in determining myeloid vs. erythroid differentiation (83–85) and PU.1 and GATA2 antagonism in myeloid vs. mast cell fate (86). Synergistic activity of PU.1 and C/EBP-α on the expression of the M-CSF receptor (87, 88) exemplifies the role of cooperative interactions (as opposed to antagonism) between transcription factors in the development of the MPS system. Much like the antagonistic interactions, the identity of the cooperative partners of PU.1 may change with the developmental stage. As an example, PU.1 partners with Runx1 for the induction of M-CSFR expression, but partners with Egr-2 for the maintenance of M-CSFR expression (89, 90). This type of 'partner switch' may involve the use of differential binding site on the same target gene (90). While general macrophage development is induced and maintained by several transcription factors interacting in a network, signaling from myeloid promoting cytokines (M-CSF, GM-CSF, G-CSF) feeds into these networks in a bi-directional manner to modulate their activity. As an example, M-CSF signaling is critical for macrophage development and the M-CSF receptor is expressed throughout MPS development (91, 92). While PU.1 induces M-CSF receptor expression (93), M-CSF signaling itself induces PU.1 expression (94). Furthermore, PU.1 can act on its promoter to potentiate its own expression (95–97). This type of interaction between cytokine signaling and transcriptional networks is critical for the induction, promotion, and homeostasis of the macrophage lineage, and are discussed further in the next section.

Tissue-resident macrophages that are derived from the common MPS lineage display remarkable diversity in phenotype, function, and transcriptional profile (Table 1) (5, 6, 8, 98). Much like early stages of myelopoiesis, transcription factors likely play a defining role in the terminal differentiation of these distinct tissue specific macrophages. Indeed, microarray-based gene expression profiling of different tissue-resident macrophages have identified several transcription factors whose expression is uniquely associated with a specific subset of tissue macrophages (7). Mouse models based on some of these transcription factors have begun to provide important insights into their roles that we now discuss below.

The red pulp region of the spleen contains resident F4/80hiVCAMhiCD11blo macrophages [red pulp macrophages (RPMs)] that phagocytose aged or damaged erythrocytes to recycle the heme-associated iron trapped within these erythrocytes (99, 100). The transcription factor Spic is highly expressed in RPM (7, 9). Importantly, mice lacking Spic were found to be deficient in RPM with disruption in normal iron homeostasis (9). Spic-deficient donor bone marrow failed to regenerate RPMs in irradiated recipients, establishing a cell-intrinsic role of Spic in RPM development. No deficiency was observed within circulating monocytes or upstream myeloid progenitors in the Spic knockout mice, suggesting that the block is likely in terminal maturation within the red pulp niche (9).

Bone marrow is the primary site of adult hematopoiesis and resident bone marrow macrophages (BMM) are important in several aspects of hematopoiesis including the maintenance of erythropoiesis during homeostasis and under stress (101, 102). BMMs and RPMs share a common function; erythrophagocytosis to recycle the precious iron (99). Remarkably, Spic was found to be highly expressed in F4/80hiVCAMhiCD11blo macrophages in the bone marrow in addition to RPM (44). Importantly, these BMM were absent in Spic-deficient mice (44). Therefore, macrophages in different location that share a common function may also share similar developmental and transcriptional pathways.

The splenic marginal zone contains two distinct macrophage subsets: marginal zone macrophages in the outer layer (expressing high levels of CD204 and SIGN-R1) and the metallophilic macrophages in the inner layer (expressing high levels of CD169) (6). Marginal zone macrophages capture blood-borne antigens and help retain marginal zone B cells, while metallophilic macrophages are thought to produce type 1 interferons in response to viral infections (103, 104).The liver X receptors (LXRs) LXRα and LXRβ are highly expressed in both subsets of macrophages in the marginal zone, with the selective requirement of LXRα for their development (10, 105). Notably, transfers of wildtype monocytes were able to generate these macrophages in LXRα deficient recipients without irradiating the host, suggesting that these macrophages may be maintained by ongoing monocyte recruitment at the steady state.

Macrophages in the peritoneal cavity (PEC) have been widely used to study macrophage biology. PEC macrophages are comprised of two subsets, large peritoneal macrophages (LPMs) and small peritoneal macrophages (SPMs), that are morphologically, functionally, and developmentally distinct (106). LPMs are the dominant fraction at the steady state, but rapidly disappear during inflammation when monocyte-derived SPMs take over. During resolution of the inflammation, the balance between LPM and SPM is gradually restored via proliferation of the LPM (106–108). Three recent studies demonstrated a role for the transcription factor GATA6 in LPM development (11, 12, 109). GATA6 was shown to be selectively expressed in LPM and its deficiency led to altered expression of many LPM-associated genes and an overall reduction in the number of these macrophages in the peritoneal cavity. Okabe and colleagues (11) demonstrated that GATA6 expression is induced by retinoic acid and that GATA6 deficiency leads to altered localization of these macrophages in the omentum instead of the peritoneal cavity. Rosas et. al. demonstrated a defect in proliferation of the LPMs in the absence of GATA6 (12), while Gautier and colleagues demonstrated a role of GATA6 in the survival of LPM (109). In bone marrow chimeras, GATA6 expressing LPMs were generated from donor cells but GATA6 expression was not detected in circulating donor monocytes. This suggests tissue specific induction of GATA6 for the maturation and maintenance of LPMs (11).

Osteoclasts are macrophages specialized in resorbing bone via their characteristic osteolytic activity and play a critical role in normal bone turnover (110). Hence, defects in genes regulating osteoclast development manifests as an increase in bone mass (osteopetrosis). Congruent with osteoclasts' identity as macrophages, disruption of factors important in general macrophage development such as PU.1 or M-CSF generates osteopetrosis in mice (111–113). Notably, unlike macrophages at other location, VEGF can compensate for M-CSF deficiency in the generation of osteoclasts in older M-CSF knockout mice (114). Factors selectively affecting the osteoclast lineage were identified in osteopetrotic mutants that displayed normal macrophages elsewhere. Mutations in the bHLH-ZIP transcription factor Mitf display such features, and were subsequently found to drive osteoclast differentiation in collaboration with PU.1 (115, 116). Another such gene is the proto-oncogene and transcription factor C-fos, whose deficiency leads to a selective reduction in the number of osteoclasts (117). Additional work uncovered the pivotal role for the receptor activator of NF-Kb (RANK) and its ligand (RANKL) in osteoclast formation and activity (118–121). Subsequently, NFATc1 was identified as the key effector downstream of RANK in osteoclastogenesis (122).

Alveolar macrophages in the lungs regulate pulmonary surfactant homeostasis to maintain normal alveolar function. Disruption in the GM-CSF signaling pathway leads to abnormal surfactant handling by these macrophages that is manifested as pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (123). More recently, deletion of the transcription factor Bach2 was reported to generate a similar phenotype suggesting a role of this transcription factor in the function of alveolar macrophages (124).

As mentioned before, the Ly6Clo subset of circulating monocytes may be considered as resident blood macrophages given their scavenging functions (57). The transcription factor NR4A1 is a nuclear receptor in the steroid thyroid receptor family that has been recently shown to regulate the development of these Ly6Clo monocytes/macrophages (125). The MDP and Ly6Chi monocytes were largely normal, suggesting a more terminal differentiation block. Further analysis suggested blocked progression of the cell cycle in NR4A1 deficient Ly6Clo monocytes that led to death of these cells in the bone marrow (125).

The examples described above demonstrate the key role of transcription factors in orchestrating tissue-resident macrophage diversity (Table 1 and Fig. 1). While the identities of transcription factors that direct the development of other tissue-specific macrophages are currently unknown, differences in cytokine requirement of some tissue-resident macrophages hint at the existence of distinct mechanisms underlying their development. As an example, Langerhans cells and microglia require the M-CSF receptor for their development like other macrophages. However, unlike other macrophages the ligand driving their development is not M-CSF, but IL-34 (126, 127). Future work will undoubtedly uncover additional details on the nexus of cytokine signaling and transcriptional networks that orchestrate terminal tissue-specific macrophage differentiation

Homeostasis of tissue-resident macrophages

The hematopoietic system is highly responsive to physiological demands where production and release of specific blood components can be modulated according to the requirements of the body. As an example, granulopoiesis and neutrophil release into circulation are both increased during an infectious or inflammatory process (128). Erythropoiesis is similarly modulated depending on the oxygen demands of the body (129). While mechanisms regulating this plasticity have been well studied in the progenitor population, the existence and details of similar processes in the mature population are unclear. Recent studies demonstrate that tissue-resident macrophages can employ their own independent homeostatic mechanisms to maintain appropriate numbers at their location. Such local mechanisms usually involve in situ proliferation or recruitment of precursors followed by in situ differentiation (Fig. 1).

The original MPS model postulated macrophages as terminally differentiated and non-dividing, despite early evidence for macrophage proliferation (130, 131). Recent studies have more conclusively demonstrated macrophage proliferation in different tissues and under different conditions, and have provided some insights into the underlying molecular mechanisms that we discuss here. Monocytes are recruited to differentiate into inflammatory macrophages and DCs during 'type1' inflammatory process typified by microbial infection or necrotic cell death (132, 133). Type 2 inflammation is characterized by production of IL-4 and local accumulation of macrophages that is exemplified by helminth infection (134, 135). Jenkins and colleagues (47) demonstrated that macrophages in the pleural and peritoneal cavities proliferate in situ after infection with the nematode Litomosoides sigmodontis or Brugia malayi, respectively. This proliferation was dependent on the cytokine IL-4. Importantly, IL-4 induced local macrophage proliferation in peritoneal cavity, pleural cavity, and liver without the requirement for infection (47). These results suggest that IL-4 mediated local proliferation can maintain tissue-macrophage homeostasis independent of bone marrow progenitors. Similarly, resident and inflammatory macrophages within the peritoneal cavity were shown to proliferate during the resolution phase of local inflammation, which was dependent on M-CSF, but not IL-4 (107, 108). M-CSF was also shown to drive macrophage proliferation within the myometrium of the growing mouse uterus (37). These findings suggest that cytokines such as M-CSF or IL-4 released from neighboring cells may help maintain tissue macrophage homeostasis. An intriguing mechanistic insight into local proliferation was provided by the observation that double deficiency of MafB and C-maf promotes proliferation of fully differentiated macrophages in vitro in the presence of M-CSF (136). Proliferation occurred without changing the differentiation status or acquisition of oncogenic properties. This uncoupling of cellular differentiation from proliferation of macrophages may be an important clue to the homeostatic mechanisms underlying the maintenance of normal macrophage numbers.

The differentiation of precursor cells into the different types of tissue-resident macrophages likely dependent on tissue-specific signals (Fig. 1). The identity of such signals is important to our understanding of tissue macrophage homeostasis as they are the common determinants of terminal differentiation for both YS- and HSC-derived macrophages. We have recently identified such a tissue-specific signal for the development of F4/80hiVCAMhi iron-recycling macrophages in the bone marrow (BMM) and spleen (RPM) (44). This signal is a tissue specific metabolite, heme that is abundant in the splenic red pulp and bone marrow. The underlying mechanism provides for a novel pathway for physiological regulation of the numbers of these macrophages. RPMs and BMM degrade heme and release the heme-associated iron back into the circulation. The transcription factor Spic is required for the development of both these macrophage subsets. Spic is constitutively repressed in monocytes by the transcriptional repressor Bach1. High levels of environmental heme in the splenic red pulp and bone marrow degrades BACH1 protein in monocytes via a proteasome-dependent mechanism (137, 138). This leads to Spic induction and the subsequent commitment of monocytes to the RPM/BMM fate. Increasing numbers of RPM/BMM restricts the availability of heme (given efficient removal of heme by these macrophages) while reduced RPM/BMM during pathologic hemolysis (given the toxic effects of high intracellular heme) increases the amount of available heme. Therefore, the availability of heme maintains the equilibrium between the precursor and the macrophages. While this mechanism plays an important role in RPM/BMM homeostasis during pathological hemolysis, its role in establishing embryonically-derived RPM and BMM is not known. It is also unclear whether all monocytes are equally capable of inducing Spic or whether this property is restricted to a yet undefined subset of monocytes.

Another tissue metabolite, retinoic acid, has been recently implicated in maintaining homeostasis of large peritoneal macrophages (LPMs) (11). Here, retinoic acid produced by omentum, along with other local factors, is thought to induce GATA6 expression in LPMs. As mentioned before, GATA6 expression in these cells were important for their proper localization, proliferation, and survival (11, 12, 109). The role of metabolite in tissue macrophage biology may also be relevant in disease processes exemplified by a recent study demonstrating the role for lactic acid from tumor cells in the functional polarization of macrophages within the tumor microenvironment (139). We suspect these emerging evidences to be indicative of a much larger role of tissue-metabolite in regulating local macrophage homeostasis that awaits further work.

Concluding remarks

Recent appreciation of the extent of heterogeneity within tissue macrophages comes with new challenges and opportunities. No longer are macrophages considered end product of a hard-wired differentiation program with monocytes as mere intermediates. Instead, the emerging picture of the macrophage lineage is that of a highly dynamic and heterogeneous system where tissue macrophages at different location possess adaptive regulatory mechanisms that ensure homeostasis of their individual lineages. A distinct role of monocytes beyond their precursor relationship with macrophages is also becoming increasingly apparent. Future work will likely uncover additional functional subsets of monocytes and macrophages whose development will like involve interplay between cytokine-signaling, local tissue-derived factors, and transcriptional networks. Understanding these regulatory pathways will be critical for our ability to modulating these cells for therapeutic applications, given their roles in many different diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (K.M.M), National Institutes of Health (T32 CA 9547-27 to M.H and K08AI106953 to M.H), and the physician-scientist training program (PSTP) in the department of pathology and immunology at the Washington University School of Medicine (M.H).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Metchnikoff E. Leçons sur la pathologie comparée de l’inflammation. Masson. 1892 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austyn JM, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur. J. Immunol. 1981;11:805–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holness CL, Simmons DL. Molecular cloning of CD68, a human macrophage marker related to lysosomal glycoproteins. Blood. 1993;81:1607–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon S, Hamann J, Lin H-H, Stacey M. F4/80 and the related adhesion-GPCRs. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2472–2476. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin H-H, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:901–944. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:1118–1128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohyama M, Ise W, Edelson BT, Wilker PR, Hildner K, Mejia C, Frazier WA, et al. Role for Spi-C in the development of red pulp macrophages and splenic iron homeostasis. Nature. 2009;457:318–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A-Gonzalez N, Guillen JA, Gallardo G, Diaz M, Rosa JV de la, Hernandez IH, Casanova-Acebes M, et al. The nuclear receptor LXRα controls the functional specialization of splenic macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:831–839. doi: 10.1038/ni.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue-specific signals control reversible program of localization and functional polarization of macrophages. Cell. 2014;157:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosas M, Davies LC, Giles PJ, Liao C-T, Kharfan B, Stone TC, O’Donnell VB, et al. The transcription factor Gata6 links tissue macrophage phenotype and proliferative renewal. Science. 2014;344:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1251414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furth R van, Cohn ZA. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1968;128:415–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez Perdiguero E, Geissmann F. Myb-Independent Macrophages: A Family of Cells That Develops with Their Tissue of Residence and Is Involved in Its Homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1101/sqb.2013.78.020032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett WE, Cohn ZA. The isolation and selected properties of blood monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1966;123:145–160. doi: 10.1084/jem.123.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furth R van, Hirsch JG, Fedorko ME. Morphology and peroxidase cytochemistry of mouse promonocytes, monocytes, and macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 1970;132:794–812. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.4.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furth R van, Diesselhoff-Den Dulk MM. The kinetics of promonocytes and monocytes in the bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 1970;132:813–828. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.4.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furth R van, Cohn ZA, Hirsch JG, Humphrey JH, Spector WG, Langevoort HL. Bull. Vol. 46. World Health Organ; 1972. The mononuclear phagocyte system: a new classification of macrophages, monocytes, and their precursor cells; pp. 845–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rieger MA, Schroeder T. Hematopoiesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Yamamura F, Naito M. Differentiation, maturation, and proliferation of macrophages in the mouse yolk sac: a light-microscopic, enzyme-cytochemical, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1989;45:87–96. doi: 10.1002/jlb.45.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi K, Naito M. Development, differentiation, and proliferation of macrophages in the rat yolk sac. Tissue Cell. 1993;25:351–362. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(93)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shepard JL, Zon LI. Developmental derivation of embryonic and adult macrophages. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2000;7:3–8. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salter MW, Beggs S. Sublime Microglia: Expanding Roles for the Guardians of the CNS. Cell. 2014;158:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FMV. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, Merkler D, Hanisch U-K, Mack M, Heikenwalder M, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graeber MB, Tetzlaff W, Streit WJ, Kreutzberg GW. Microglial cells but not astrocytes undergo mitosis following rat facial nerve axotomy. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;85:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yona S, Kim K-W, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B, Brija T, et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, Prinz M, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, Kim MV, Bivona MR, Liu K, Pamer EG, et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, Fehling HJ, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, Liu K, et al. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagliani E, Shi C, Nancy P, Tay C-S, Pamer EG, Erlebacher A. Coordinate regulation of tissue macrophage and dendritic cell population dynamics by CSF-1. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1901–1916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capotondo A, Milazzo R, Politi LS, Quattrini A, Palini A, Plati T, Merella S, et al. Brain conditioning is instrumental for successful microglia reconstitution following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:15018–15023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205858109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leuschner F, Rauch PJ, Ueno T, Gorbatov R, Marinelli B, Lee WW, Dutta P, et al. Rapid monocyte kinetics in acute myocardial infarction are sustained by extramedullary monocytopoiesis. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:123–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, McNagny KM, Rossi FMV. Infiltrating monocytes trigger EAE progression, but do not contribute to the resident microglia pool. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landsman L, Varol C, Jung S. Distinct differentiation potential of blood monocyte subsets in the lung. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md. 2007;178:2000–2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2000. @@1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landsman L, Jung S. Lung macrophages serve as obligatory intermediate between blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md. 2007;179:3488–3494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3488. @@1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovtunovych G, Eckhaus MA, Ghosh MC, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Rouault TA. Dysfunction of the heme recycling system in heme oxygenase 1-deficient mice: effects on macrophage viability and tissue iron distribution. Blood. 2010;116:6054–6062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haldar M, Kohyama M, So AY-L, Kc W, Wu X, Briseño CG, Satpathy AT, et al. Heme-mediated SPI-C induction promotes monocyte differentiation into iron-recycling macrophages. Cell. 2014;156:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jakubzick C, Gautier EL, Gibbings SL, Sojka DK, Schlitzer A, Johnson TE, Ivanov S, et al. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2013;39:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, Jones LH, Finkelman FD, Rooijen N van, MacDonald AS, et al. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 2011;332:1284–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1204351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, Wagers A, Peters W, Charo I, Weissman IL, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoeffel G, Wang Y, Greter M, See P, Teo P, Malleret B, Leboeuf M, et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1167–1181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lambrecht BN. Alveolar macrophage in the driver’s seat. Immunity. 2006;24:366–368. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guilliams M, Kleer I De, Henri S, Post S, Vanhoutte L, Prijck S De, Deswarte K, et al. Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long-lived cells in the first week of life via GM-CSF. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1977–1992. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoeffel G, Wang Y, Greter M, See P, Teo P, Malleret B, Leboeuf M, et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1167–1181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, Greenshtein L, Gildor B, Margalit R, Kalchenko V, et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, Hedrick CC, et al. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C(low) monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jakubzick C, Gautier EL, Gibbings SL, Sojka DK, Schlitzer A, Johnson TE, Ivanov S, et al. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2013;39:599–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010;22:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhargava P, Lee C-H. Role and function of macrophages in the metabolic syndrome. Biochem. J. 2012;442:253–262. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman DR, Cumano A, et al. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naik SH, Sathe P, Park H-Y, Metcalf D, Proietto AI, Dakic A, Carotta S, et al. Development of plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell subtypes from single precursor cells derived in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1217–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Schmid MA, Ohteki T, Jarrossay D, Manz MG. Identification of clonogenic common Flt3+M-CSFR+ plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/ni1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko A-C, Krijgsveld J, Feuerer M. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cecchini MG, Dominguez MG, Mocci S, Wetterwald A, Felix R, Fleisch H, Chisholm O, et al. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1994;120:1357–1372. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dai X-M, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, Dominguez MG, Russell RG, Kapp S, Sylvestre V, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKenna HJ, Stocking KL, Miller RE, Brasel K, Smedt T De, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski CR, et al. Mice lacking flt3 ligand have deficient hematopoiesis affecting hematopoietic progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Blood. 2000;95:3489–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from Flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to Flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:305–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Xie H, Andres-Aguayo L de, Graf T. Reprogramming of committed T cell progenitors to macrophages and dendritic cells by C/EBP alpha and PU.1 transcription factors. Immunity. 2006;25:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, Graf T. Stepwise reprogramming of B cells into macrophages. Cell. 2004;117:663–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feng R, Desbordes SC, Xie H, Tillo ES, Pixley F, Stanley ER, Graf T. PU.1 and C/EBPalpha/beta convert fibroblasts into macrophage-like cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:6057–6062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711961105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McKercher SR, Torbett BE, Anderson KL, Henkel GW, Vestal DJ, Baribault H, Klemsz M, et al. Targeted disruption of the PU.1 gene results in multiple hematopoietic abnormalities. EMBO J. 1996;15:5647–5658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeKoter RP, Singh H. Regulation of B lymphocyte and macrophage development by graded expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288:1439–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bakri Y, Sarrazin S, Mayer UP, Tillmanns S, Nerlov C, Boned A, Sieweke MH. Balance of MafB and PU.1 specifies alternative macrophage or dendritic cell fate. Blood. 2005;105:2707–2716. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dahl R, Walsh JC, Lancki D, Laslo P, Iyer SR, Singh H, Simon MC. Regulation of macrophage and neutrophil cell fates by the PU.1:C/EBPalpha ratio and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1029–1036. doi: 10.1038/ni973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reddy VA, Iwama A, Iotzova G, Schulz M, Elsasser A, Vangala RK, Tenen DG, et al. Granulocyte inducer C/EBPalpha inactivates the myeloid master regulator PU.1: possible role in lineage commitment decisions. Blood. 2002;100:483–490. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang DE, Zhang P, Wang ND, Hetherington CJ, Darlington GJ, Tenen DG. Absence of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor signaling and neutrophil development in CCAAT enhancer binding protein alpha-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:569–574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kelly LM, Englmeier U, Lafon I, Sieweke MH, Graf T. MafB is an inducer of monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1987–1997. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moriguchi T, Hamada M, Morito N, Terunuma T, Hasegawa K, Zhang C, Yokomizo T, et al. MafB is essential for renal development and F4/80 expression in macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5715–5727. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00001-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rekhtman N, Radparvar F, Evans T, Skoultchi AI. Direct interaction of hematopoietic transcription factors PU.1 and GATA-1: functional antagonism in erythroid cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1398–1411. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang P, Zhang X, Iwama A, Yu C, Smith KA, Mueller BU, Narravula S, et al. PU.1 inhibits GATA-1 function and erythroid differentiation by blocking GATA-1 DNA binding. Blood. 2000;96:2641–2648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nerlov C, Querfurth E, Kulessa H, Graf T. GATA-1 interacts with the myeloid PU.1 transcription factor and represses PU.1-dependent transcription. Blood. 2000;95:2543–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Walsh JC, DeKoter RP, Lee HJ, Smith ED, Lancki DW, Gurish MF, Friend DS, et al. Cooperative and antagonistic interplay between PU.1 and GATA-2 in the specification of myeloid cell fates. Immunity. 2002;17:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang DE, Hetherington CJ, Meyers S, Rhoades KL, Larson CJ, Chen HM, Hiebert SW, et al. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and AML1 (CBF alpha2) synergistically activate the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1231–1240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petrovick MS, Hiebert SW, Friedman AD, Hetherington CJ, Tenen DG, Zhang DE. Multiple functional domains of AML1: PU.1 and C/EBPalpha synergize with different regions of AML1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:3915–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hoogenkamp M, Lichtinger M, Krysinska H, Lancrin C, Clarke D, Williamson A, Mazzarella L, et al. Early chromatin unfolding by RUNX1: a molecular explanation for differential requirements during specification versus maintenance of the hematopoietic gene expression program. Blood. 2009;114:299–309. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krysinska H, Hoogenkamp M, Ingram R, Wilson N, Tagoh H, Laslo P, Singh H, et al. A two-step, PU.1-dependent mechanism for developmentally regulated chromatin remodeling and transcription of the c-fms gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:878–887. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01915-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pixley FJ, Stanley ER. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sasmono RT, Oceandy D, Pollard JW, Tong W, Pavli P, Wainwright BJ, Ostrowski MC, et al. A macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor-green fluorescent protein transgene is expressed throughout the mononuclear phagocyte system of the mouse. Blood. 2003;101:1155–1163. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang DE, Hetherington CJ, Chen HM, Tenen DG. The macrophage transcription factor PU.1 directs tissue-specific expression of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:373–381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mossadegh-Keller N, Sarrazin S, Kandalla PK, Espinosa L, Stanley ER, Nutt SL, Moore J, et al. M-CSF instructs myeloid lineage fate in single haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;497:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leddin M, Perrod C, Hoogenkamp M, Ghani S, Assi S, Heinz S, Wilson NK, et al. Two distinct auto-regulatory loops operate at the PU.1 locus in B cells and myeloid cells. Blood. 2011;117:2827–2838. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen H, Ray-Gallet D, Zhang P, Hetherington CJ, Gonzalez DA, Zhang DE, Moreau-Gachelin F, et al. PU.1 (Spi-1) autoregulates its expression in myeloid cells. Oncogene. 1995;11:1549–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Okuno Y, Huang G, Rosenbauer F, Evans EK, Radomska HS, Iwasaki H, Akashi K, et al. Potential autoregulation of transcription factor PU.1 by an upstream regulatory element. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:2832–2845. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2832-2845.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gordon S, Plűddemann A. Tissue macrophage heterogeneity: issues and prospects. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013;35:533–540. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ganz T. Macrophages and systemic iron homeostasis. J. Innate Immun. 2012;4:446–453. doi: 10.1159/000336423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:606–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chow A, Huggins M, Ahmed J, Hashimoto D, Lucas D, Kunisaki Y, Pinho S, et al. CD169+ macrophages provide a niche promoting erythropoiesis under homeostasis and stress. Nat. Med. 2013;19:429–436. doi: 10.1038/nm.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ramos P, Casu C, Gardenghi S, Breda L, Crielaard BJ, Guy E, Marongiu MF, et al. Macrophages support pathological erythropoiesis in polycythemia vera and β-thalassemia. Nat. Med. 2013;19:437–445. doi: 10.1038/nm.3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Geijtenbeek TBH, Groot PC, Nolte MA, Vliet SJ van, Gangaram-Panday ST, Duijnhoven GCF van, Kraal G, et al. Marginal zone macrophages express a murine homologue of DC-SIGN that captures blood-borne antigens in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:2908–2916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eloranta ML, Alm GV. Splenic marginal metallophilic macrophages and marginal zone macrophages are the major interferon-alpha/beta producers in mice upon intravenous challenge with herpes simplex virus. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999;49:391–394. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.A-González N, Castrillo A. Liver X receptors as regulators of macrophage inflammatory and metabolic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:982–994. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ghosn EEB, Cassado AA, Govoni GR, Fukuhara T, Yang Y, Monack DM, Bortoluci KR, et al. Two physically, functionally, and developmentally distinct peritoneal macrophage subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:2568–2573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davies LC, Rosas M, Jenkins SJ, Liao C-T, Scurr MJ, Brombacher F, Fraser DJ, et al. Distinct bone marrow-derived and tissue-resident macrophage lineages proliferate at key stages during inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1886. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Davies LC, Rosas M, Smith PJ, Fraser DJ, Jones SA, Taylor PR. A quantifiable proliferative burst of tissue macrophages restores homeostatic macrophage populations after acute inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gautier EL, Ivanov S, Williams JW, Huang SC-C, Marcelin G, Fairfax K, Wang PL, et al. Gata6 regulates aspartoacylase expression in resident peritoneal macrophages and controls their survival. J. Exp. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1084/jem.20140570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Edwards JR, Mundy GR. Advances in osteoclast biology: old findings and new insights from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011;7:235–243. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tondravi MM, McKercher SR, Anderson K, Erdmann JM, Quiroz M, Maki R, Teitelbaum SL. Osteopetrosis in mice lacking haematopoietic transcription factor PU.1. Nature. 1997;386:81–84. doi: 10.1038/386081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wiktor-Jedrzejczak WW, Ahmed A, Szczylik C, Skelly RR. Hematological characterization of congenital osteopetrosis in op/op mouse. Possible mechanism for abnormal macrophage differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 1982;156:1516–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yoshida H, Hayashi S, Kunisada T, Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Okamura H, Sudo T, et al. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990;345:442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Niida S, Kaku M, Amano H, Yoshida H, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Tanne K, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor can substitute for macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the support of osteoclastic bone resorption. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:293–298. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hodgkinson CA, Moore KJ, Nakayama A, Steingrímsson E, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Arnheiter H. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell. 1993;74:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90429-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Luchin A, Suchting S, Merson T, Rosol TJ, Hume DA, Cassady AI, Ostrowski MC. Genetic and physical interactions between Microphthalmia transcription factor and PU. 1 are necessary for osteoclast gene expression and differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36703–36710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grigoriadis AE, Wang ZQ, Cecchini MG, Hofstetter W, Felix R, Fleisch HA, Wagner EF. c-Fos: a key regulator of osteoclast-macrophage lineage determination and bone remodeling. Science. 1994;266:443–448. doi: 10.1126/science.7939685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hsu H, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Solovyev I, Colombero A, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:3540–3545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Morony S, Tarpley J, Capparelli C, Scully S, et al. osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Li J, Sarosi I, Yan XQ, Morony S, Capparelli C, Tan HL, McCabe S, et al. RANK is the intrinsic hematopoietic cell surface receptor that controls osteoclastogenesis and regulation of bone mass and calcium metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, Nishina H, Isshiki M, Yoshida H, Saiura A, et al. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Trapnell BC, Carey BC, Uchida K, Suzuki T. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, a primary immunodeficiency of impaired GM-CSF stimulation of macrophages. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nakamura A, Ebina-Shibuya R, Itoh-Nakadai A, Muto A, Shima H, Saigusa D, Aoki J, et al. Transcription repressor Bach2 is required for pulmonary surfactant homeostasis and alveolar macrophage function. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2191–2204. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hanna RN, Carlin LM, Hubbeling HG, Nackiewicz D, Green AM, Punt JA, Geissmann F, et al. The transcription factor NR4A1 (Nur77) controls bone marrow differentiation and the survival of Ly6C-monocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:778–785. doi: 10.1038/ni.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Greter M, Lelios I, Pelczar P, Hoeffel G, Price J, Leboeuf M, Kündig TM, et al. Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity. 2012;37:1050–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang Y, Szretter KJ, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Rossini C, Cella M, Barrow AD, et al. IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:753–760. doi: 10.1038/ni.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bugl S, Wirths S, Müller MR, Radsak MP, Kopp H-G. Current insights into neutrophil homeostasis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012;1266:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Paulson RF, Shi L, Wu D-C. Stress erythropoiesis: new signals and new stress progenitor cells. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2011;18:139–145. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834521c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Daems WT, Bakker JM de. Do resident macrophages proliferate? Immunobiology. 1982;161:204–211. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(82)80075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Naito M, Umeda S, Yamamoto T, Moriyama H, Umezu H, Hasegawa G, Usuda H, et al. Development, differentiation, and phenotypic heterogeneity of murine tissue macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;59:133–138. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:669–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Soehnlein O, Lindbom L. Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nri2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Anthony RM, Rutitzky LI, Urban JF, Stadecker MJ, Gause WC. Protective immune mechanisms in helminth infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:975–987. doi: 10.1038/nri2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Voehringer D, Shinkai K, Locksley RM. Type 2 immunity reflects orchestrated recruitment of cells committed to IL-4 production. Immunity. 2004;20:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Aziz A, Soucie E, Sarrazin S, Sieweke MH. MafB/c-Maf deficiency enables self-renewal of differentiated functional macrophages. Science. 2009;326:867–871. doi: 10.1126/science.1176056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ogawa K, Sun J, Taketani S, Nakajima O, Nishitani C, Sassa S, Hayashi N, et al. Heme mediates derepression of Maf recognition element through direct binding to transcription repressor Bach1. EMBO J. 2001;20:2835–2843. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zenke-Kawasaki Y, Dohi Y, Katoh Y, Ikura T, Ikura M, Asahara T, Tokunaga F, et al. Heme induces ubiquitination and degradation of the transcription factor Bach1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6962–6971. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02415-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Colegio OR, Chu N-Q, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]