Abstract

Analogies between humans and animals based on facial resemblance have a long history. We report evidence for reverse anthropomorphism and the extension of facial stereotypes to lions, foxes, and dogs. In the stereotype extension, more positive traits were attributed to animals judged more attractive than con-specifics; more childlike traits were attributed to those judged more babyfaced. In the reverse anthropomorphism, human faces with more resemblance to lions, ascertained by connectionist modeling of facial metrics, were judged more dominant, cold, and shrewd, controlling attractiveness, babyfaceness, and sex. Faces with more resemblance to Labradors were judged warmer and less shrewd. Resemblance to foxes did not predict impressions. Results for lions and dogs were consistent with trait impressions of these animals and support the species overgeneralization hypothesis that evolutionarily adaptive reactions to particular animals are overgeneralized, with people perceived to have traits associated with animals their faces resemble. Other possible explanations are discussed.

Comparisons of impressions of animals and humans has recently been a focus of psychological research, with a special issue of Social Cognition (April, 20081 devoted to anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits to animals, and the converse dehumanization, the attribution of animal traits to humans. With the exception of the interesting finding that trait impressions of dogs, like those of humans, are influenced by appearance (Kwan, Gosling, & John, 2008), the role of appearance is not considered in this innovative body of research. Yet, the idea that humans share traits with the animals they resemble, the focus of the present research, has a long history.

The Physiognomica, written in ancient Greece (often ascribed to Aristotle), includes colorful assumptions about people based on their resemblance to animals, For example, it argues that just as animals with coarse hair are brave—the lion, the wild boar, the wolf—so are people with coarse hair. People with smooth, silky hair, on the other hand, are timid as lambs (quoted in Lavater, 1783/1879, pp. 206–207). In the 16th century, Della Porta expressed the logic of animal analogies in syllogisms like: “All parrots are talkers, all men with such noses are like parrots, therefore all such men are talkers” (Della Porta, 1586). Le Brun, a 17th-century French artist produced engravings comparing the facial form and character of animals and men (Sorel, 1980), and Lavater, a prominent physiognomist of that era emphasized the intrinsic meaning of different animal appearance qualities:

Were the lion and the lamb, for the first time, placed before us, had we never known such animals…still we could not resist the impression of the courage and strength of the one, or the weakness and sufferance of the other…A man whose…forehead and nose should resemble that of the lion, would, certainly, be no common man. (Lavater, 1783/1879, p. 212, 214)

It is noteworthy that animal analogies transcend cultures. Chinese folklore categorizes people according to the animal year in which they were born, with individuals presumed to have traits similar to the animal of their birth year. Appearance also plays a role in this reverse anthropomorphism, as shown in an ancient and popular Chinese allegory in which a Chinese monk and his disciples travel to India in search of Buddhist sutras. The disciple in monkey form is rebellious and resourceful, while another in pig form is lazy and greedy (Wu, ~800). Remnants of such reverse anthropomorphism are found in modern caricatures and in linguistic metaphors, such as leonine, foxy, sheepish, bully, bird-brained, dove, hawk, and chicken.

The species lace overgeneralization hypothesis (SFO; Zebrowitz, 1996; Zebrowitz, 1997) captures the reverse anthropomorphism shown in folk psychology by giving facial resemblance to animals a role in the process of attributing traits to humans. Specifically, it is proposed that the evolutionary importance of responding appropriately to various species, such as avoiding lions and approaching lambs, has produced a strong preparedness to react to species appearance qualities that is overgeneralized. The result is that people are judged to have the traits of the animals whom their faces resemble.1

To our knowledge, there has been no previous scientific investigation of SFO. We used connectionist modeling to test the hypothesis for two reasons. First, connectionist models provide objective assessments of physical resemblance to various species that are not biased by trait impressions of the faces, as subjective ratings of resemblance may be. Second, the similarity-based generalizations we tested are a natural property of connectionist models, which are powerful nonlinear statistical modeling tools. The feasibility of training a connectionist network to differentiate faces that vary in species is supported by previous research in which they have been trained to differentiate faces varying in sex (Golomb, Lawrence, & Sejnowski, 1991), race (O’Toole, Abdi, Deffenbacher, & Bartlett, 1991), emotion (Zebrowitz, Kikuchi, & Fellous, 2010), age, and fitness (Zebrowitz, Fellous, Mignault, & Andreoletti, 2003; Zebrowitz, Kikuchi, & Fellous, 2007). Connectionist networks trained to discriminate animal and human faces will react to untrained human faces according to their similarity to the animals vs. humans. Thus, network activation to the untrained faces captures the network’s overgeneralization of species information to those faces. If the neural network’s assessment of the physical similarity of human faces to a particular species predicts impressions of their traits, this will provide support for SFO2

We investigated resemblance to lions, foxes, and dogs. Because lions are viewed as king of the beasts, we predicted that human faces with greater resemblance to lions would be judged more dominant. In keeping with the simile “like a fox” that refers to guile and cleverness, we predicted that human faces with greater resemblance to foxes would be judged more shrewd. Because dogs are viewed as man’s best friend, we predicted that human faces with greater resemblance to dogs would be judged as warmer. Recognizing that selective breeding techniques during the domestication of dogs has yielded variations in appearance and behavioral traits (Coren, 1994), we examined resemblance to Labrador retrievers, a breed ranked low in actual aggression/disagreeableness (Draper, 1995). To verify the animal-trait associations that served as the basis of our SFO predictions, we assessed trait impressions of the lions, foxes, and dogs depicted in the photos used for the connectionist modeling.

We also used the animal trait impressions to test the generalizability to animals of two human face stereotypes. One is the babyface stereotype, whereby child-like traits are attributed more to babyfaced than maturefaced adults (Montepare & Zebrowitz, 1998; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2008). The extension of this stereotype to adult members of other species would be consistent with Lorenz’s (1943) observation that facial cues to neoteny are similar across humans and other animals as well as with supporting empirical evidence (Pittenger, Shaw, & Mark, 1979). The second facial stereotype is the attractiveness halo effect, whereby positively-valued traits are attributed more to attractive than unattractive adults (Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991). The extension of this stereotype to other species would be consistent with the fact that people’s judgments of attractiveness are responsive to averageness/prototypicality, whether judging a human face, fish, or bird (Halberstadt & Rhodes, 2003; Langlois & Roggman, 1990).

METHOD

TRAINING AND GENERALIZATION FACES

Human training faces were 30 Caucasian adults (15 male; M age = 17.35 years, SD = .43) used in previous connectionist modeling research (Zebrowitz et al., 2003). Lion training faces were adult males drawn from websites. Dog faces were 30 adult Labrador retrievers (15 male; approximately 2 years old), obtained from breeder websites. Fox faces were 30 adult red foxes (Canidae Vulpes) gathered from wildlife photo websites. All faces were cropped to show only head and neck; eyes were lined up on a horizontal plane. Generalization faces were 107 Caucasian young adults (60 male; M age = 17.77 years, SD = .42) with neutral expressions, drawn from previous connectionist modeling studies (Zebrowitz et al., 2003). All were 17–18 years.

FACE RATINGS

Human training and generalization faces had been previously rated by 16 judges (8 male) on three 7-point trait scales relevant to the hypotheses (dominant/submissive, warm/cold, shrewd /na ve) and on three 7-point appearance scales (unattractive/attractive and maturefaced/baby faced, no smile/big smile), with ratings on the smile scale confirming that the expressions were neutral (M = 1.54, SD = .54; Zebrowitz et al., 2003), Animal training faces were rated on the same scales (except for smile) by 8 additional judges (4 male).

FACIAL METRICS

Facial metrics for human faces were taken from Zebrowitz et al. (2003), and the same procedure was used to generate metrics for the animal faces. Computer software was used to mark 64 points on digitized images of each face (Figure 1). Points were marked by two judges on a subset of 12 animal faces, with different judges for each species. After establishing inter-judge reliability, each judge marked 9 of the remaining 18 faces of that species. Facial metrics (Figure 2 left) were calculated from the points using automatic procedures written in Visual Basic and Excel. To adjust for variations in head size, each metric was normalized by head length (LO). All facial metrics with acceptable interrater reliability across all species (Mean r = .88) were selected as facial inputs to the network training. In addition to thirteen simple facial distances shown in Figure 2, right, there were two compound measures: Cheekbone prominence (W4/W1) and ratio of the lower face to nose length (C1/N3).

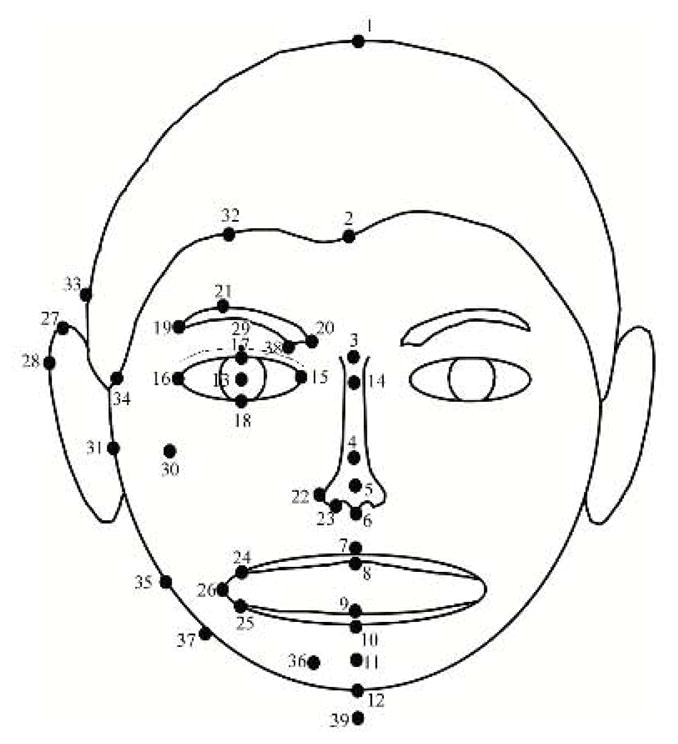

FIGURE 1.

Location of points. When identical points are marked on the right and left sides, only those on the person’s right side are indicated.

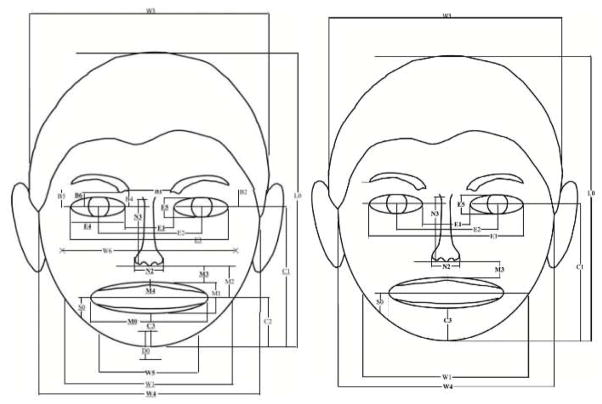

FIGURE 2.

Left: Location of all simple distances generated from paints. Right: Location of the 13 simple distances used as inputs in networks trained to differentiate animal from human faces and the normalization distance. LO, SO indicates length of the jowl, if any.

CONNECTIONIST MODELING

Modeling paralleled previous research. Three networks were trained: one to differentiate lion from human faces; one to differentiate fox from human faces; one to differentiate Labrador from human faces. In the training phase, facial metrics were provided as input to artificial neural networks that were trained with supervised learning to differentiate randomly selected animal (N = 20) and human (N = 20) faces. Next the trained network was tested on the remaining animal (N = 10) and human (N = 10) faces to document successful training. Finally, the trained network was provided with input metrics from the 107 human generalization faces. These three phases were repeated for 20 trials to establish a reliable index of network activation by each generalization face. We used standard back-propagation neural networks with one input layer with 15 facial metrics, one hidden layer with 3 nodes, and one output layer with two units (animal and human) rescaled into reciprocal graded values ranging from 0% to 100% activation. Each input node projected to any or all of the hidden nodes and the hidden nodes projected to the two output units (neutral and one of the emotions). The input weight matrices connecting the layers consisted of numbers between −1 and 1. All units were nonlinear and mapped the weighted sum of their inputs to their output using a sigmoidal transfer function. Other parameters were a .02 learning rate, 4000 training epochs, and a .2 error goal. This generated three dependent variables for each generalization face: average activation of the lion output unit, the fox output unit, and the dog output unit, each assessed across 20 trials.

RESULTS

NETWORK ACTIVATION

Training was successful, with 99.25% of training faces and 98.5% of test faces correctly identified, averaged across 20 trials. Unsurprisingly, given that generalization faces were all human, they produced lower activation of the animal than the human output units (M = 14.33, SD = 2.89 for lions, M = 12.01, SD = 2.30, for foxes, M = 12.68, SD = 3.88, for dogs), with activation of the human face unit equal to 100 minus these values, all ps < .0001. Nevertheless, there was variability in the extent to which the human faces activated the animal units (range = 8.32–21.80 for lions; 8.12–19.16 for foxes; 7.12–26.90 for dogs).

PREDICTING IMPRESSIONS OF HUMAN FACES FROM ACTIVATION OF THE SPECIES OUTPUT UNITS

Multiple regression analysis on each trait rating determined whether impressions of human faces were predicted from the extent to which they activated the output units trained to respond to lions, foxes, and dogs, controlling for face sex, attractiveness, and babyfaceness, which may influence impressions. Activation of the three animal species output units were entered together as predictors in each regression in order to determine the independent effects on impressions of resemblance to lions, foxes, and dogs. Standardized regression weights are reported.

The three regression models were significant: R2 = .29, F(6,100) = 6.94, p < .001 for impressions of warmth; R2 = .63, F(6,100) = 28.60, p < .001 for dominance; R2 = .56, F(6,100) = 20.80, p < .001 for shrewdness. In each model, output units trained to recognize different animal faces had a significant influence on impressions over and above effects of the control variables.

Human generalization faces eliciting greater activation of the dog unit were judged warmer, b = .38, t = 2.17, p = .03, as predicted. They also were judged as marginally less shrewd, b = −.25, t = 1.75, p = .08, than those bearing less resemblance to Labrador retrievers, but not different in dominance, b = −.17, t = 1.33, p = .18. Human faces eliciting greater activation of the lion unit were perceived as marginally more dominant, b = .15, t = 1.66, p = .10, as predicted. They were also judged as marginally less warm, b = minus;.23, t = 1.88, p = .06, and significantly more shrewd, b = .33. t = 3.41, p = .001, than those bearing less resemblance to lions. Contrary to prediction, greater activation of the fox unit did not predict impressions of greater shrewdness, b = .04, t < 1, p = .76. Resemblance to foxes also did not predict impressions of warmth, b = −.23, t = 1.58, p = .12 or dominance, b = .08, t < 1, p = .44, for which we had no a priori hypotheses.

ANIMAL TRAIT IMPRESSIONS

Reliability analyses revealed acceptable inter-judge agreement in impressions of each trait (standardized Cronbach alphas ranged from .75 to .88), attractiveness (standardized Cronbach alpha = .83), and babyfaceness (standardized Cronbach alpha = .69). Ratings of each individual animal face were therefore averaged across judges for subsequent analyses.

Differences in Trait Impressions of Lions, Foxes, and Labradors

We compared trait impressions of the three species to determine whether differences in impressions of the actual animals paralleled differences in impressions of humans who varied in their resemblance to the animals. We performed separate one-way analyses of variance for each trait impression with 3 levels (lion, fox, dog), using judges’ mean ratings of each of the 30 individual animals from a given species as the unit of analysis. Species differed significantly in perceived dominance, F(2,87) = 10.64, p < .001. As predicted, lions (M = 4.92, SD = .74) were perceived as more dominant than dogs (M = 4.18, SD = .52), t (58) = 4.48, p < .001, but, contrary to prediction, they did not differ significantly from foxes (M = 4.91, SD= .83), t < 1. Species also differed in perceived shrewdness, F(2,87) = 24.93, p < .001, with foxes (M = 5.16, SD = .76) rated higher than both lions (M = 4.38, SD = .50), t (58) = 4.70, p < .001, and dogs (M = 4.02, SD = .62), t (58) = 6.33, p < .001, as predicted. Also, lions, were judged shrewder than dogs, t (58) = 2.41, p = .02. Finally, as predicted, species differed significantly in perceived warmth, F(2,87) = 73.02, p < .001, with dogs (M = 5.34, SD = .64) rated higher than both lions (M = 3.81, SD = .88), t(58) = 7.92, p < .001, and foxes (M = 3.02, SD = .78), t(58) = 12.90, p < .001.

Face Stereotypes Within Species

To determine whether the attractiveness halo effect and the babyface stereotype hold true for animal faces, we performed partial correlation analyses assessing the relationship of each appearance quality to trait impressions with the other quality controlled. Consistent with the childlike stereotype of more babyfaced humans as warmer, less dominant, and less shrewd, more babyfaced lions were rated less dominant, r(27) = −.56, p = .001, marginally warmer, r(27) = .34, p = .07, and marginally less shrewd, r(27) = −.36, p = .06. More babyfaced foxes were also rated less dominant, r(27) = −.54, p <.01, warmer, r(27) = .60, p < .001, and less shrewd, r(27) = −.61, p < .001. More babyfaced dogs were rated less dominant, r(27) = −.39, p = .04, but not significantly warmer, r(27) = .24, p = .22 or less shrewd, r(27) = −.25, p = .19, although the trends were as predicted. Consistent with the positive stereotype of attractive humans as warmer and more dominant, more attractive lions were rated significantly warmer, r(27) = .56, p < .01, and more dominant, r(27) = 44, p = .02. More attractive foxes also were rated significantly warmer, r(27) = .49, p < .01, but not more dominant, r(27) = .25, p = .19. More attractive dogs were rated significantly more dominant, r(27) = .54, p < .01 but not warmer, r(27) = .24, p = .22.

DISCUSSION

Although animal analogies may no longer take the explicit form found in ancient Greece and China or during the heyday of physiognomy three centuries ago, they persist in tacit appearance-trait associations. Humans with an objectively leonine appearance, as ascertained by the extent to which their facial metrics activated a neural network trained to respond to lions, were judged marginally more dominant and cold, as well as more shrewd, like the imperious king of the beasts. These results are consistent with ratings of lions as more dominant, cold, and shrewd than dogs in the present study. In contrast, to the effects of a leonine appearance, people with more objective resemblance to Labrador retrievers were judged warmer, a trait for which man’s best friend has been bred, as well as marginally less shrewd, perhaps capturing the perceived openness of dogs. These results are consistent with the tendency to rate dogs higher in warmth and lower in shrewdness than either lions or foxes. They also complement evidence that priming people with particular animals elicits behavior consistent with the traits associated with that animal (Chartrand, Fitzsimons, & Fitzsimons, 2008), inasmuch as showing people human faces that resemble particular animals primes impressions that are consistent with the animal’s traits.

The effects of a leonine and canine appearance are consistent with the SFO hypothesis that the evolutionary importance of responding appropriately to animals of various species is overgeneralized, with people rated higher on traits associated with the animals their faces resemble. However, although foxes were rated as shrewder than either lions or dogs, as expected, people with an objectively more fox-like appearance were not rated as more shrewd. Perhaps our evolutionary history has created less responsiveness to the appearance of foxes than to the more evolutionarily significant species of lions, which preyed upon early humans, and dogs, which were domesticated by early humans.

Whereas trait impressions of people whose faces show more resemblance to lions or Labradors are consistent with SFO, one may question whether this is indeed the mechanism for the observed effects. This question has at least three components. First, one may question the SFO presumption that trait impressions of different species found in folklore and in the current study are accurate. However, it does seem unquestionable that dogs afford more warmth to humans than lions do, and that lions are more likely to dominate than dogs are. Second, one may question the SFO presumption that the traits of different species are conveyed by their facial appearance. However, there is some evidence for truth to the claim that the morphological traits of nonhuman animals are honest indicators of their behavioral traits. In particular, domestication yields similar morphological changes across species, such as floppy ears, wavy or curly hair, and a more infantile skull and snout shape as compared with wild animals from the same species (Trut, 1999; Trut, Oskina, & Kharlamova, 2009). Third, and more generally, one may question whether the influence of resemblance to animals on trait impressions has an evolutionary origin. Of course, this presumption cannot be proved, but its plausibility requires consideration of alternative possibilities.

One alternative explanation is that media portrayals of different animals, as in cartoons, sagas of Lassie and Rin Tin Tin, and the anti-archetypal cowardly lion in Wizard of Oz, create associations between particular animal faces and particular traits. Although such portrayals may contribute to those associations, this explanation begs the question of the origin of media depictions. Another alternative to SFO is that perceivers are responding to abstract facial qualities, some of which convey dominance and happen to be shared by lions and some people, and others of which convey warmth and happen to be shared by Labradors and other people. Possible contenders are the degree to which faces resemble the abstract qualities of attractiveness, babyfaceness, masculinity or an emotion expression, since these qualities influence impressions of dominance and warmth/valence, two pre-potent dimensions on which faces are evaluated (e.g., Todorov, Said, Engell, & Oosterhof, 2008; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2008; Zebrowitz et al., 2010). Although our analyses ruled out attractiveness and babyfaceness, variations in masculinity and emotion resemblance remain possible explanations. For example, a larger face width to height ratio, is more characteristic of men than women and predicts perceived and actual aggressiveness in humans (Carre & McCormick, 2008; Carre, McCormick, & Mondlich, 2009). Perhaps this metric is more characteristic of lion than Labrador faces, and perhaps greater resemblance to a smile and less resemblance to anger is more characteristic of Labrador than lion faces.3

Determining whether species differ in facial masculinity and emotion resemblance would be interesting, but such effects would raise the equally interesting question of why their faces look the way they do (Marsh, Adams, & Kleck, 2005). One intriguing explanation is consistent with SFO, namely that facial cues have evolved to facilitate not only intra-species interaction, but also inter-species interaction, yielding overlapping facial cues to species, sex, emotion, and/or maturity. Indeed, it has been argued that similarities in face perception across species (Leopold & Rhodes, 2010; Tate, Fischer, Leigh, & Kendrick, 2006; Zebrowitz & Zhang, in press) may serve adaptive hetero-specific interaction, including “recognition of threatening species, which is important for survival, as well as the playful or nurturing behavior sometimes observed between members of different species living together under unnatural conditions” (Leopold & Rhodes, 2010, p. 44).

The possibility that species have evolved to manifest facial qualities that advertise their traits is consistent with the above mentioned finding that changes in appearance are a by-product of breeding for certain traits (Trut, 1999; Trut et al., 2009). Since dog breeding has produced differences in both traits and appearance, it would be interesting to investigate whether variations in human resemblance to different breeds predict variations in trait impressions just as does resemblance to different species. Investigations of impressions of people who resemble species other than those examined in the present study also would be worthwhile.

In addition to demonstrating a reverse anthropomorphism, attributing animal traits to humans who resemble them, we also found that human facial stereotypes are generalized to animals. The babyface stereotype was shown in the perceived dominance of all species and the shrewdness and warmth of foxes and lions. The attractiveness halo effect was shown in the perceived warmth of foxes and lions and the dominance of dogs and lions. These findings extend previous evidence for different trait impressions of different dog breeds (Gosling, Kwan, & John, 2003; Kwan et al., 2008). Perceivers’ trait impressions are sensitive to variations in attractiveness and babyfaceness even within the breed of Labrador retrievers. These extensions of facial stereotypes to other species and our evidence for reverse anthropomorphism demonstrate the promise of elevating animal analogies from folklore to science.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [MH066836 and K02MH72603].

The authors thank Masako Kikuchi for her assistance with the connectionist modeling.

Footnotes

This hypothesis does not imply that de-humanization of outgroup members (Haslam, 2006) derives from actual resemblance to nonhuman animals, although dehumanization often includes visual images that depict such resemblance (Keen, 2004)

We use connectionist modeling as a mathematical technique for generating an objective index of the structural similarity of a face to a particular category of faces, not to test alternative models of face processing (cf. Valentine, 1995).

To explore the masculinity of species resemblance, we performed a regression analysis with face sex as the dependent variable rather than a control variable and activation by the three animal output units as predictor variables, controlling for attractiveness and babyfaceness, R2 = .23, F (5, 101) = 5.92, p < .001. Resemblance to foxes predicted a female face, b = .56, t = 3.98, p < .001; resemblance to Labradors predicted a male face, b =−.58, t = 3.27, p = .001; resemblance to lions did not predict face sex, b = −.10, t < 1.

References

- Carre JM, McCormick CM. In your face: facial metrics predict aggressive behaviour in the laboratory and in varsity and professional hockey players. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2008;275:2651–2656. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carre JM, McCormick CM, Mondloch CJ. Facial structure is a reliable cue of aggressive behavior. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1194–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coren ST. The intelligence of dogs: Canine consciousness, and capabilities. New York: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, Fitzsimons GIM, Fitzsimons GJ. Automatic effects of anthropomorphized objects on behavior. Social Cognition. 2008;26:198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta G. De Humana physiognomica. In: Wechsler J, editor. A human comedy: Physiognomy and caricature in 19th century Paris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1586. p. 179. footnote 112. [Google Scholar]

- Draper TW. Canine analogs of human personality factors. The journal of General Psychology. 1995;122:241–252. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1995.9921236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Ashmore RD, Makhijani MG, Longo LC. What is beautiful is good, but: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Golomb BA, Lawrence DT, Sejnowski TJ. Sexnet: A neural network identifies sex from human faces. In: Lippman JMRP, Touretzky DS, editors. Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 3. San Mateo, CA: Kaufmann; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Kwan VSY, John OP. A Dog’s got personality: A cross-species comparative approach to personality Judgments in dogs and humans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:1161–1169. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt J, Rhodes G. It’s not Just average faces that are attractive: Computer-manipulated averageness makes birds, fish, and automobiles attractive. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2003;10:149–156. doi: 10.3758/bf03196479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N. Dehumanization: An Integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:252–264. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen S. Faces of the enemy: Reflections of the hostile imagination. New York: Harper & Row; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan VSY, Gosling SD, John OP. Anthropomorphism as a special case of social perception: A cross-species social relations model analysis of humans and dogs. Social Cognition. 2008;26:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Roggman LA. Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science. 1990;1:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lavater JC. In: Essays on physiognomy. 16. Holcroft T, translator. London William Tegg and co; 1783/1879. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, Rhodes G. A comparative view of face perception. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2010;124:235–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz KZ. Die angeborenen Formen Moglicher Vererbung. Zeitschrift fur Tier-psychologie. 1943;5:235–409. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Adams RB, Jr, Kleck RE. Why do fear and anger look the way they do? Form and social function in facial expressions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:73–86. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montepare JM, Zebrowitz LA. Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social Judgments. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 30. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 93–163. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole AJ, Abdi H, Deffenbacher KA, Bartlett JC. Classifying faces by race and sex using an auto-associative memory trained for recognition. In: Hammond KJ, Gentner D, editors. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Sciences Society. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger JB, Shaw RE, Mark LS. Perceptual information for the age level of faces as a higher order invariant of growth. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1979;5:478–493. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.5.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorel E, editor. Resemblances: Amazing faces by Charles Le Brun. New York: Harlin Quist; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tate AJ, Fischer H, Leigh AE, Kendrick KM. Behavioural and neurophysiological evidence for face identity and face emotion processing in animals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2006;361:2155–2172. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov A, Said CP, Engell AD, Oosterhof NN. Understanding evaluation of faces on social dimensions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trut L. Early canid domestication: The farm-fox experiment. American Scientist. 1999;87:160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Trut L, Otkina I, Kharlamova A. Animal evolution during domestication: The domesticated fox as a model. Bioessays. 2009;31:349–360. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine TE. Cognitive and computational aspects of face recognition. London: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. In: Journey to the West. Yu AC, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1977. (~800) [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA. Physical appearance as a basis for stereotyping. In: McRae N, Hewstone M, Stangor C, editors. Foundation of stereotypes and stereotyping. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 79–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA. Reading faces: Window to the soul? Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Fellous JM, Mignault A, Andreoletti C. Trait impressions as overgeneralized responses to adaptively significant facial qualities: Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:194–215. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0703_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Kikuchi M, Fellous JM. Are effects of emotion expression on trait impressions mediated by baby-faceness? Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:648–662. doi: 10.1177/0146167206297399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Kikuchi M, Fellous JM. Facial resemblance to emotions: Group differences, impression effects, and race stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:175–189. doi: 10.1037/a0017990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Montepare JM. Social psychological face perception: Why appearance matters. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:1497–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Zhang Y. Origins of impression formation in animal and infant face perception. In: Decety J, Cacioppo J, editors. The handbook of social neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]